Abstract

Green-stained amniotic fluid, often referred to as meconium-stained amniotic fluid (MSAF) is present in 5% to 20% of patients in labor and has been traditionally considered an obstetrical hazard. Discolored amniotic fluid has been attributed to the presence of heme catabolic products from the passage of fetal colonic content (meconium), intra-amniotic bleeding, or both. The frequency of green-stained amniotic fluid increases as a function of gestational age reflecting maturation of the gastrointestinal system and reaches approximately 27% in post-term gestation. Prior to the introduction of routine continuous fetal heart rate monitoring, green-stained amniotic fluid during labor was associated with fetal acidemia (umbilical artery pH < 7.00), neonatal respiratory distress, seizures, and was considered a risk factor for cerebral palsy. Hypoxia has been considered the main mechanism responsible for fetal defecation and MSAF; however, most fetuses with MSAF do not have fetal acidemia. Nonetheless, in the absence of fetal heart rate abnormalities, MSAF is not associated with fetal acidemia. Intra-amniotic infection/inflammation has emerged as an important factor in MSAF in term and preterm gestations, and green-stained amniotic fluid is a risk factor for maternal and neonatal infections. Whether intra-amniotic infection/inflammation results in discoloration of amniotic fluid via oxidative stress or the passage of meconium has not been determined. Two randomized clinical trials suggest that, in patients with MSAF, intrapartum administration of antibiotics decreases the rate of clinical chorioamnionitis. Meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS) is a severe complication typical of term newborns which develops in 5% of cases of MSAF. MAS is attributed to the mechanical and chemical effects of aspirated meconium coupled with local and systemic fetal inflammation. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials suggests that amnioinfusion may decrease the rate of MAS. Routine naso/oropharyngeal suctioning and tracheal intubation in cases of MSAF have not been shown to be beneficial and are no longer recommended in obstetric practice. Histologic staining of the membranes with meconium has been used in the context of medical legal litigation to try to time the occurrence of fetal injury. This has been largely based on the results of in vitro experiments. However, extrapolation of these findings to the clinical setting is unwarranted. Experimental studies in animals and observational studies in human fetuses suggest that fetal defecation is a physiologic phenomenon throughout pregnancy.

Introduction

Green-stained amniotic fluid, often referred to as meconium-stained amniotic fluid (MSAF), has been considered an obstetrical hazard for centuries. It has become increasingly clear that not all green-stained amniotic fluid is attributable to meconium and that not all meconium is green. This article will review the composition of meconium, the clinical significance of MSAF and its implications for obstetrical management, the pathophysiology of meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS) and we will close with some thoughts about the physiology of fetal defecation.

What is meconium?

The word ‘‘meconium’’ is derived from the Greek word mekoni, which means ‘‘poppy juice” or “opium-like,” referring to the belief that fetal exposure to meconium would lead to neonatal sleepiness or depression,1–3 a concept generally attributed to Aristotle1, 2, 4

Meconium is the fetal colonic content, which is mainly composed of water (72% to 80%),2 exfoliated skin cells, lanugo, vernix caseosa, and gastrointestinal secretions5–16 (Table 1). The typical greenish-yellow color of meconium is attributed to bile pigments.7–11, 17, 18 Bilirubin, a product of heme catabolism, is the main pigment in meconium, detectable in the fetal liver and gallbladder from 14 weeks of gestation19. While the intestinal content of children and adults is rich in bacteria, meconium during fetal life is sterile,20 as shown by metagenomic studies21 that controlled for contamination of reagents and by studies in non-human primates and mice.22, 23

Table 1.

Meconium composition

| • Water (70%–80%) |

| • Intestinal epithelial cells |

| • Squamous cells |

| • Vernix caseosa |

| • Fetal hair |

| • Amniotic fluid |

| • Bile pigments (eg, bilirubin, zinc-coproporphyrin) |

| • Bile acids (eg, chenodeoxycholic and cholic acids) |

| • Pancreatic enzymes |

| • Free fatty acids |

Meconium as an obstetrical hazard

Völtern in 1687 reported that MSAF was associated with fetal death,24 an observation subsequently confirmed by multiple authors25–28(Figure 1). Indeed, MSAF is considered a risk factor for neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy,3, 29–31 neonatal sepsis,3, 32, 33 neonatal seizures,34 MAS,35–39 and cerebral palsy.40–43 Several clinical conditions (eg, prolonged labor, fetal growth restriction, oligohydramnios, vaginal breech delivery, etc.) have been related to the passage of meconium into the amniotic fluid,44–51 and the risk factors for MSAF are reported in (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Meconium-stained neonate at 39+4 weeks gestation. Figure 1A shows yellow-greenish discoloration of fetal skin at different body sites. The evidence of peripheral cyanosis is shown in Figure 1B (lips), 1C (ears) and 1D (fingertips). Meconium is also present in the ear canal (Figure 1C).

Table 2.

Risk factors for meconium-stained amniotic fluid (MSAF)

| • Post-term pregnancy |

| • Prolonged labor |

| • Clinical chorioamnionitis |

| • Fetal growth restriction |

| • Preeclampsia |

| • Oligohydramnios |

| • Vaginal breech delivery |

| • Maternal drugs (eg, cocaine, castor oil, bowel purgatives) |

| • Herbal substances (eg,’isihlambezo’) |

| • Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy |

Factors associated with meconium-stained amniotic fluid

1. Gestational age

The rate of MSAF increases as a function of gestational age and can reach 27% at 42 weeks of gestation44, 45, 50, 52–60 (Figure 2). A subset of post-term neonates is affected by the post maturity syndrome, defined as fetal growth restriction in a post-term gestation.61 The presence of MSAF is a criteria of stage II post maturity syndrome proposed by Clifford61 (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

The frequency of meconium stained amniotic fluid as a function of gestational age. Modified from Balchin et al 50

Figure 3.

Meconium in post maturity syndrome with fetal death at 40 weeks of gestation. The neonate shows the classical features of post maturity syndrome characterized by loss of vernix caseosa, loss of subcutaneous fat and presence of macerated, wrinkled skin (Figures 3A–E). Meconium passage is documented by the greenish-yellow discoloration of the anus, (Figure 3F) the discoloration of the skin (Figure 3A) and the green-yellow staining of placental membranes (Figure 3G).

The higher rate of meconium passage reported in term gestations is thought to reflect maturation of the gastrointestinal system. Observational studies in guinea pigs62 and monkeys63 have shown that intestinal peristalsis increases with advancing gestational age. Similar evidence in human fetuses was reported in studies documenting fetal gastrointestinal motility with amniography.64

The following endocrine factors have been implicated in the increased frequency of meconium passage at term: 1) motilin, a gut hormone produced by entero-endocrine cells in the duodenum,65 capable of inducing intestinal peristalsis.66 The concentrations of motilin are significantly higher in umbilical cord blood from term neonates compared to preterm neonates67 and from those with MSAF at term;68, 69 2) cortisol, which increases in fetal plasma at the time of parturition,70, 71 can also induce intestinal motility as demonstrated in an observational study of pregnant monkeys where intra-amniotic injection of glucocorticoids resulted in meconium passage;72 and 3) corticotropin-releasing factor, a hormone that increases with gestational age,73–76 can also accelerate fetal gut motility.77–82

2. Fetal hypoxia

MSAF has been associated with fetal acidemia34, 83, 84 and chronic hypoxia (estimated by erythropoietin concentrations in umbilical cord blood).85–87 The largest study to examine the relationship between MSAF and fetal acidemia included 42,709 term pregnancies of which 8,136 had MSAF. Meconium was associated with a significantly higher rate of an umbilical artery pH ≤ 7.00 [7% (56/8136) vs 3% (95/34,573); p < 0.001; odds ratio (OR)=2.5; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.8–3.4]34 (Table 3). However, most neonates born to mothers with MSAF do not have evidence of metabolic acidemia at birth.56, 85, 88–93 Indeed, in a recent retrospective study including 3,590 deliveries, MSAF was not associated with umbilical artery acidemia and 80% of neonates with MSAF had a pH ≥ 7.20.54 These conflicting results between the two largest studies, may be explained by differences in the use of intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring. In the first study,34 surveillance was performed with intermittent auscultation, while, in the second study,54 continuous electronic fetal heart rate monitoring was used. It is possible that improved surveillance allows earlier detection of a compromised fetus, thus the association between MSAF and umbilical artery acidemia was not observed.

Table 3.

Outcomes in neonates born with MSAF compared to neonates born with clear amniotic fluid

| Outcome | MSAF | Clear AF | P value | Odds ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total infants | 8136 | 34,573 | |||

| Apgar score ≤ 3 | |||||

| 1minute | 123 (15) | 201 (6) | < 0.001 | 2.6 | 2.1–3.2 |

| 5minutes | 14 (2) | 19 (1) | 0.003 | 3.1 | 1.6–6.0 |

| Umbilical artery pH ≤ 7.00 | 56 (7) | 95 (3) | < 0.001 | 2.5 | 1.8–3.4 |

| Apgar score ≤ 3 at 5 minutes and pH ≤ 7.00 | 9 (1) | 5 (0.1) | < 0.001 | 7.6 | 3.0–19.3 |

| Special care nursery admission | 193(24) | 248 (7) | < 0.001 | 3.3 | 2.8–3.9 |

| Respiratory distress* |

223 (27) | 288 (8) | < 0.001 | 3.3 | 2.8–3.9 |

| IVH grade III or IV | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 0.5 | 2.1 | 0.2–22.2 |

| Seizures in the first 24hours | 17 (2) | 13 (0.4) | < 0.001 | 5.6 | 2.9–10.5 |

| Cesarean | |||||

| Total | 1170 (14) | 2420 (7) | < 0.001 | 2.1 | 1.9–2.2 |

| Dystocia | 609 (7) | 1328 (4) | < 0.001 | 1.9 | 1.8–2.1 |

| Fetal distress | 472 (6) | 628 (2) | < 0.001 | 3.2 | 2.9–3.6 |

Modified from Nathan et al34

It is widely accepted that fetal hypoxia leads to meconium passage.34, 83, 84, 94 However, experimental studies have challenged this view. For example, constricting the maternal aorta in pregnant rabbits to induce maternal acidemia and fetal distress is not associated with meconium passage95 and neither is acute inhalational hypoxia of pregnant sheep sufficient to drop the fetal PO2.96, 97 Similarly, repeated cord occlusion leading to fetal acidemia is not associated with meconium passage in fetal sheep. However, a role for the autonomic nervous system in the regulation of pathologic fetal defecation has been proposed. Indeed, sympathetic system blockade, achieved chemically with 6-hydroxy-dopamine, in the same experimental paradigm of cord occlusion does lead to meconium passage.98 It is also noteworthy that normal fetal defecation in animal studies is observed in the absence of fetal hypoxemia or acidemia.99

3. Intra-amniotic infection/inflammation

MSAF is associated with microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity in term and preterm gestations.57, 58, 100, 101 In patients with preterm labor and intact membranes, those with green-colored amniotic fluid have a higher rate of positive amniotic fluid cultures for bacteria than those with clear amniotic fluid [33% (10/30) versus 11% (75/677) p=0.001].58 Mazor et al102 confirmed the association between MSAF and the presence of bacteria in the amniotic fluid in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes [38 (17/45) vs 11% (15/135); p<0.001] and also with clinical chorioamnionitis [22 (10/45) vs 6% (8/135); p=0.003].102 The same association between meconium and intraamniotic infection has been reported at term. In patients with clinical chorioamnionitis, those with MSAF have a higher rate of microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity and bacterial endotoxin compared to those with clear amniotic fluid [(19.6% (13/66) vs 4.7% (2/42); p<0.05) and (46.9% (31/66) vs 4.7% (2/42); p<0.001), respectively].100 Additionally, the concentrations of interleukin (IL)-6 are higher in MSAF, providing evidence of an intra-amniotic inflammatory response.100

The green discoloration of amniotic fluid in the context of intra-amniotic infection/inflammation has been attributed either to oxidative stress in the amniotic cavity or passage of meconium. Bacteria can elicit intra-amniotic inflammation, which, in turn, leads to the generation of reactive oxygen species103, 104 capable of inducing oxidation of heme catabolic products such as bilirubin.105, 106 We have previously proposed that bacteria and amniotic fluid with inflammatory products, when ingested by the fetus, may stimulate bowel peristalsis.58, 100 An alternative explanation for the association between intra-amniotic infection/inflammation and MSAF is that meconium enhances bacterial proliferation by serving as a growth factor57, 58, 102 and by inhibiting the bacteriostatic properties of amniotic fluid or antagonizing host defense systems,107–109 thus increasing the risk of infection.

Prolonged gestation, fetal hypoxia and intra-amniotic infection/inflammation could explain only a subset of patients with MSAF. However, the cause for the remaining cases has yet to be elucidated. Omics analysis of amniotic fluid stained with meconium would provide an insight into the pathophysiology of MSAF and could allow the identification of biomarkers that can serve in the stratification of patients according to the etiology of MSAF.

Assessment of meconium-stained amniotic fluid

Typically, MSAF is diagnosed after membranes rupture or by amniocentesis. On occasion, sonographic particulate matter in amniotic fluid raises the suspicion for MSAF. The ultrasound criteria originally proposed for the identification of MSAF are as follows:110 1) a diffuse echogenic pattern throughout the amniotic cavity; 2) a clear contrast between the amniotic fluid and the umbilical vessels; and 3) layering in the more dependent areas.110 However, this appearance is not specific to meconium and can be seen in the presence of vernix or even blood.111–115 In a study of 278 patients who were scanned 24 hours prior to delivery, the prevalence of echogenic amniotic fluid was 3.2% and, of these patients, 44% (4/9) had MSAF with a sensitivity of 14% and a positive predictive value of 44%.116 Therefore, ultrasound has limited diagnostic value to identify this condition.

Green-colored amniotic fluid has been detected at the time of amniocentesis in the midtrimester for genetic indications or in the third trimester. In the past, serial transabdominal amniocenteses were used as a method of surveillance in women with prolonged gestations to detect post-maturity syndrome117 or in patients with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy to assess the risk of fetal death.118 However, serial amniocenteses for these indications have been abandoned because of the lack of evidence that detection of meconium and induction of labor improved pregnancy outcomes. 119

Meconium in amniotic fluid has been classified according to its thickness into grades 1 to 3 (grade 1: lightly stained amniotic fluid, green or yellow; grade 2: green- or yellow-stained amniotic fluid with some particulate matter; and grade 3: dense meconium with “pea-soup” consistency).120 However, the most commonly used classification in obstetric practice divides MSAF into “thick” and “thin” (Figure 4). Thick meconium is associated with higher rates of abnormal fetal heart tracings,54, 83, 121, 122 MAS,121, 123–127 neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission,84, 127–129 need for neonatal ventilation,123 hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy of the neonate,123, 130 small for gestational age,123 and low Apgar scores. 32, 83, 124, 125, 128, 129 Similarly, higher rates of cesarean delivery, 6, 66, 79, 143, 213, 217 puerperal endometritis,131 clinical chorioamnionitis, 84, 131 intrapartum fever,54 and intraamniotic infection132 have been reported in women with thick MSAF (Table 4). Obstetrical conditions, such as oligohydramnios associated with post-term pregnancies133, 134 or uteroplacental insufficiency, 122, 135–138 altered fetal swallowing,139 and an increased amount of meconium passage as well as impaired reabsorption of meconium by amniotic membrane macrophages,140, 141 have been implicated in the genesis of thick MSAF.

Figure 4.

Meconium-stained amniotic fluid. Figure 4A and 4B shows green meconium. Figure 4C and 4D “thin” meconium which is yellow. The traditional concept is that meconium is green when first passed and overtime can become yellow.

Table 4.

Adverse neonatal and maternal outcomes associated with thick meconium-stained amniotic fluid (MSAF)

| Neonatal outcomes | Maternal outcomes |

|---|---|

| Abnormal fetal heart rate tracing | Cesarean delivery |

| Meconium aspiration syndrome | Puerperal endometritis |

| Neonatal Intensive Care Unit admission | Clinical chorioamnionitis |

| Need for neonatal ventilation | Intrapartum fever |

| Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy of the neonate | Intra-amniotic infection |

| Small for gestational age | |

| Low APGAR score |

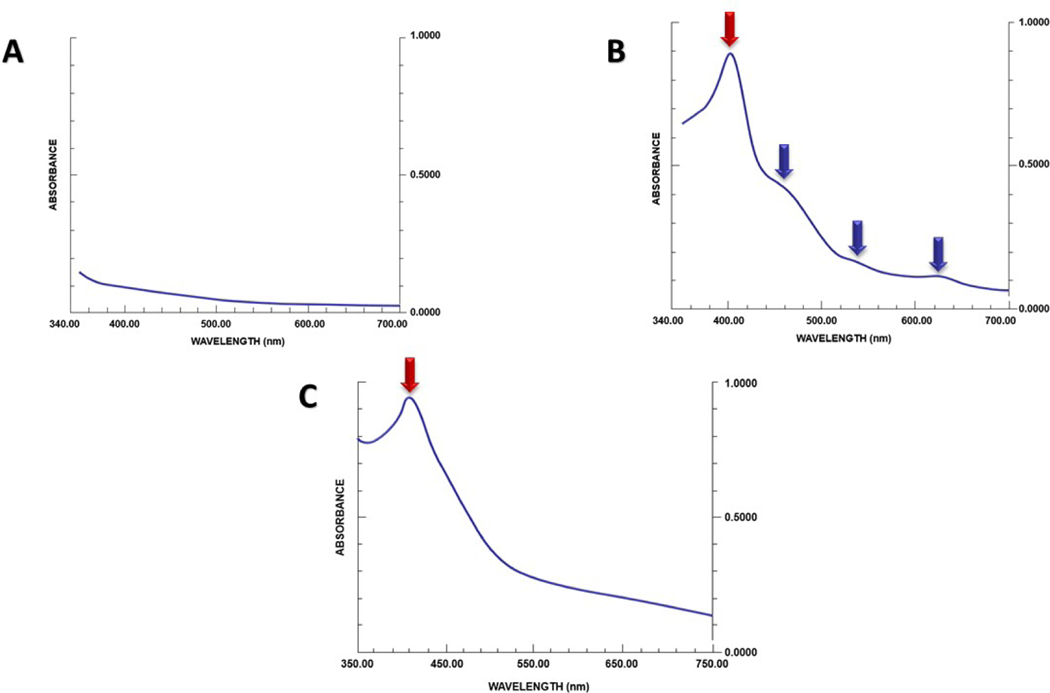

A quantitative approach to assess meconium load in the amniotic fluid is the “meconium-crit.”142 This test is based on the same principle as that used to calculate the hematocrit with a capillary tube, and results well correlate with meconium concentrations142 but may not reflect neonatal outcomes. Other methods such as spectrophotometry143 and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy have also been proposed as tools to estimate meconium concentration in amniotic fluid. The band height in the spectrophotometric tracing correlates with meconium concentrations143 (Figure 5). Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy can also be used to quantitate meconium in amniotic fluid based upon the T1 and T2 relaxation times that decrease with increasing concentrations of meconium.144, 145 Neither spectrophotometry, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, nor meconium-crit have been implemented in clinical practice.

Figure 5.

Spectrophotometric analysis of amniotic fluid. The absorption spectra of amniotic fluid (after centrifugation) with different concentrations of meconium is shown. The band height is linearly correlated with meconium concentration. Modified from Molcho et al143

Green-stained amniotic fluid is not always indicative of meconium

The traditional view that all green-stained amniotic fluid is due to meconium has been challenged. Meconium has been described as green, and this color is attributed to biliverdin,146 an intermediate product of heme catabolism that can be subsequently reduced to bilirubin in the reticuloendothelial system through a reversible reaction (Figure 6). Indeed, the oxidation of bilirubin leads to biliverdin.106, 147, 148 Bilirubin, a yellow pigment, is consistently detected in meconium,17, 19 while there is paucity of evidence that this is the case for biliverdin.17

Figure 6.

The catabolism of heme. Heme is first transformed into biliverdin and then to bilirubin in the reticuloendothelial system. The first reaction consists in the conversion of ferric heme to biliverdin, and it is catalyzed by the heme oxygenase system. Subsequently, biliverdin reductase reduces biliverdin to bilirubin. COOH: carboxyl group; NADPH: Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate Hydrogen; NADP+: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate. Modified from Rodwell et al159

Green- and brown-discolored amniotic fluid at the time of mid trimester amniocenteses has been reported in 1.2% to 8% of cases149–158 and is associated with pregnancy loss in 9% of cases.157 Brown amniotic fluid was considered an indicator of intraamniotic hemorrhage, whereas green fluid was attributed to the presence of meconium. Spectrophotometric analysis of midtrimester discolored amniotic fluid performed by Hankins et al reported that green and brown discolorations were attributable to previous episodes of intra-amniotic bleeding as reflected by the presence of free hemoglobin.156 Clear amniotic fluid has a smooth absorption spectrum (Figure 7), whereas the contamination with either blood or meconium typically adds an absorption peak near 400nm (also known as “Soret band”)159, 160 attributable to the presence of hemoglobin in the former and of meconium pigments (eg, bilirubin) in the latter.155, 156, 159, 161 However, the absorption spectrum in intra-amniotic bleeding shows additional peaks (attributed to oxyhemoglobin, methemoglobin, and methemalbumin) that can be used in the differential diagnosis with MSAF. 155 Amniotic fluid contaminated with meconium at term usually tests negative for hemoglobin and shows no extra peaks at spectrophotometric analysis (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Spectrophotometric analysis of amniotic fluid at different gestational ages.

7A. Normal term amniotic fluid spectrum. The typical spectrum shows a smooth declining slope without peaks suggesting the lack of chemical compounds absorbing light.

7B. Typical spectrophotometric tracing of discolored second-trimester amniotic fluid with a maximum peak near 405nm (“Soret band”, red arrow) and several secondary absorption peaks at 450, 550 and 620 (blue arrows).

7C. Spectrophotometric tracing of term meconium-stained amniotic fluid. There is a peak at 405nm (red arrow) and a smooth declining slope without additional peaks. Modified from Alger et al155

Maternal implications of meconium-stained amniotic fluid

MSAF is associated with intraamniotic infection,58, 100, 101 clinical chorioamnionitis,47, 58, 102, 131, 162–166 puerperal endometritis,131, 167 post-cesarean infection,168 postpartum hemorrhage,167, 169–171 and dehiscence of perineal lacerations.172, 173 The association between meconium and infection provides a rationale for exploring the role of antibiotic administration in MSAF. A systematic review of two randomized clinical trials174–176 in women with MSAF allocated to intravenous ampicillin/sulbactam versus placebo showed that intrapartum antibiotic administration reduced the frequency of clinical chorioamnionitis (relative risk (RR) 0.36; 95% CI 0.21–0.62) but not the frequency of postpartum endometritis (RR 0.50; 95% CI 0.18–1.38), neonatal sepsis (RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.21–4.76) and NICU admission (RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.39–1.78). An alternative approach is antibiotic administration selectively to patients who are at a particular high risk for infection, determined by a high concentration of IL-6 or matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8) in amniotic fluid obtained through a transcervical catheter coupled with point-of-care testing.177 The value of this approach should be the subject of prospective studies.

Neonatal implications of meconium-stained amniotic fluid: meconium aspiration syndrome

MSAF occurs in 5% to 20% of deliveries at term3, 35, 84, 163, 178–180 and is a risk factor for neonatal complications133, 134, 139, 140, 142, 143 such as MAS,35–39 neonatal sepsis,3, 32, 33 pulmonary disease,84, 181 neonatal seizures34, 182 and long-term neurological disability (eg, cerebral palsy).40–42

MAS is defined as respiratory distress in term neonates born to mothers with MSAF that cannot be otherwise explained. (Figure 8) MAS is a cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality,1, 3, 30, 35, 88, 122, 183 and the reason why only 5%35–39 of infants exposed to meconium develop MAS remains an enigma. (Figure 9). Typically, MAS affects neonates with an intrauterine event that causes intrapartum or antepartum fetal hypoxia129, 163, 178, 184–189 leading to meconium passage, fetal gasping,190, 191 and meconium aspiration before birth. However, a large fraction of neonates with MAS do not have acidemia at birth55, 88–93 (Table 5); therefore, alternative mechanisms must be involved in the pathogenesis of this syndrome. Meconium itself can cause local damage in the fetal lungs through 1) a mechanical effect, which can cause airway obstruction leading to atelectasis or air trapping within the bronchioles and the alveoli 101, 192, 193 (Figure 10); 2) a chemical effect of meconium content (eg, free fatty acids, bile salts, pancreatic phospholipases) that can result in surfactant inactivation;194, 195 and 3) a local inflammatory response (pneumonitis) 192, 193, 196, 197 that can lead to a decreased pulmonary function.198, 199 Persistent pulmonary hypertension occurs in 20% to 40% of infants with MAS. Several mechanisms have been implicated in the development of PPHN in MAS.200 Parenchymal lung disease with poor alveolar recruitment and decreased functional residual capacity (FRC) or hyperinflation with increased FRC contribute to elevations in pulmonary vascular resistance (PRV).201 Additionally, the release of chemically vasoactive mediators, such as endothelin-1 (ET-1), thromboxane-A2 and prostaglandins, has also been shown to contribute to the development of PPHN in MAS.202 Vascular remodeling changes such as hyperplasia of the vascular media and interstitium, narrowing in the vessel lumen, tortuosity of the arteries, and muscularization of the alveolar septal arterioles have been described in MAS.203, 204

Figure 8.

Chest x-ray showing bilateral patchy opacifications.

Figure 9.

Autopsy of a neonate with evidence of meconium in the trachea from meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS). The arrow points to fetal hair within the trachea.

Table 5.

Prevalence of neonatal acidemia in meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS)

| Author, date | Neonatal umbilical artery pH at birth in MAS cases | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH ≥ 7.20 | pH < 7.20 | pH < 7.10 | pH <7.00 | |

| Lee, 201655 | (58.3%) (7/12) | 41.7% (5/12) | 16.7% (2/12) | 8.3% (1/12) |

| Blackwell, 200188 | 60.4% (29/48) | 39.6% (19/48) | na | na |

| Yeomans, 198990 | 83.3% (5/6) | 16.7% (1/6) | na | na |

| Trimmer, 199191 | 50–100% (1–2/2) | 0–50% (0–1/2) | na | na |

Figure 10.

Meconium in the fetal bronchiole (Figure 9A) and alveoli (Figure 9B). The arrows indicate fetal anucleated squamous cells, one of the components of meconium. Staining is H&E

In the context of intra-amniotic infection/inflammation, fetal swallowing of amniotic fluid containing bacteria,205, 206 endotoxin,58, 100, 101, 207 alarmins,205, 208–214 inflammatory mediators,100, 101, 215–217 and phospholipase A2 can induce a fetal systemic inflammatory response (FIRS) resulting in diffuse lung injury.55, 101, 218 The combination of pulmonary inflammation and capillary damage/leakage occurring during FIRS could explain the association between MSAF, intra-amniotic inflammation/infection, and MAS. 55 The knowledge that FIRS is a risk factor for the development of MAS has clinical implications. Indeed, umbilical cord blood concentrations of IL-6 or C reactive protein could assist in the identification of infants who have systemic inflammation.

Prophylactic intrapartum transcervical amnioinfusion in cases with MSAF has been proposed to reduce the rate of MAS and other adverse neonatal outcomes. Subsequently, this procedure was abandoned after the publication of a meta-analysis that reported no evidence of benefit in terms of reduction of the rate of MAS (RR 0.59; 95% CI 0.28–1.25), 5-minute Apgar score < 7 (RR 0.90; 95% CI 0.58–1.41), and cesarean delivery (RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.73–1.10). Prophylactic amnioinfusion seems to have a role only in clinical settings with limited peripartum surveillance as it helps to reduce the risk of MAS (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.13–0.47).219 However, these results and interpretation have been subject of debate.220, 221 Recently, a new meta-analysis that reassessed the value of prophylactic amnioinfusion in the presence of MSAF reported a reduction of MAS by 67% (pooled OR 0.33; 95% CI 0.21–0.51). Amnioinfusion has been proposed to dilute thick meconium, thereby diminishing the mechanical and the proinflammatory effects. This metaanalysis is reported in detail in this issue of AJOG.

Since neonatal airway obstruction by meconium is believed to be causal of MAS, several approaches have been proposed to remove meconium from the fetal and neonatal airways to prevent aspiration (reviewed in detail by Wiswell183). Routine endotracheal intubation was introduced in the 1970s after Burke-Strickland and Edwards222 as well as Gregory223 reported a favorable experience with this practice. Gregory et al found that 56% of newborns delivered from mothers with MSAF had already meconium in the trachea at the time of birth, and that in 10% of the cases, meconium was present below the vocal cords even though not visible in the mouth or pharynx.223 The authors further noted a reduction in the frequency of pneumothorax, mechanical ventilation, and continuous positive airway pressure after early endotracheal intubation.223

Other investigators advocated complete removal of meconium from the oropharynx and nasopharynx before the delivery of the chest and onset of air breathing as a method to prevent meconium aspiration. This procedure was performed with either a bulb syringe or a suction catheter. The combined approach consisted of immediate oro/nasopharyngeal suctioning at the time of delivery of the fetal head, followed by endotracheal intubation and suctioning after birth. This management was reported to reduce the rate of MAS from 1.9% (18/947) to 0.4% (1/273) with endotracheal aspiration alone.224 The combined approach has been used in labor and delivery units for decades;225 however, subsequent studies questioned efficacy226–228 and safety.229–233 Indeed, complications such as laryngeal lesions leading to stridor and hoarseness,229 bradycardia,230 apnea,230 hypoxemia, and desaturation231–233 were reported. Observational studies also showed no benefit in the reduction of MAS.234–238 Such findings led to the design and execution of randomized controlled trials181, 229, 239–244 and subsequent meta-analyses,226–228 which demonstrated that neither routine suctioning of the oro/nasopharynx after the delivery of the head,226 nor intubation with tracheal suctioning in both vigorous227 and non-vigorous newborns,228 prevented or altered the frequency and course of MAS. Consensus has emerged that infants born to mothers with MSAF should no longer routinely receive suctioning at birth, whether or not they are vigorous. The current recommendation is that management should be guided by general neonatal resuscitation principles rather than a pre-specified approach.245

Placental histopathological findings in meconium-stained amniotic fluid

MSAF often results in green-yellow staining of the chorioamniotic membranes and umbilical cord at gross placental inspection (Figure 3G). Microscopically, meconium-laden macrophages are the hallmark of this condition. These phagocytic cells can be identified by the presence of brown-yellow-colored cytoplasmic granules on hematoxylin and eosin staining140, 246 (Figure 11). However, similar granules can be observed in the placenta of patients who had intraamniotic bleeding.246 Histochemistry staining for hemosiderin238–24247–249 (eg, Perls’ Prussian blue, Gomori or Berlin blue) can assist in the differential diagnosis of bleeding versus meconium. The rationale is that bilirubin in meconium does not contain iron, while hemosiderin (an iron-storage complex in cells) does. Pathologists rely on this approach to diagnose meconium staining of the fetal membranes. If iron staining is negative, the diagnosis of meconium is made. Meconium contains zinc coproporphyrin I (ZnCP-I),10, 250 and investigators have recently developed a monoclonal antibody for this compound and identified this molecule in chorioamniotic membranes.250 This would provide direct evidence of the presence of meconium.

Figure 11.

The chorioamniotic membranes in a case of meconium-stained amniotic fluid (stained with H&E). Meconium is visualized within macrophages (blue arrows) in the amnion and chorion stroma (Blue squared parenthesis). Meconium-laden macrophages are recognized by the pink staining of the cytoplasm after excluding hemosiderin pigment with Prussian blue staining (not shown).

Meconium in the chorioamniotic membranes has been used in medical legal litigations to time adverse events and to formulate arguments about medical negligence. Desmond et al reported that immersion of the lower extremities of neonates in MSAF would cause mild yellow staining of toenails in four to six hours, whereas yellow staining of the vernix caseosa would take 12 to 14 hours.251 The time required to stain the chorioamniotic membranes has been subject of debate. For example, Miller et al incubated discs of chorioamniotic membranes with meconium and reported that meconium-laden macrophages were present in the amnion after one hour of exposure and in the chorion after three hours.252 A subsequent experiment in which the exposure to meconium was restricted to the amnion found that it took 24–48 hours for a substantial number of meconium-laden macrophages to be observed.140 This finding has been interpreted as indicating that meconium staining of the membranes reflects fetal defecation that occurred at least one day before delivery of the placenta. By contrast to these in vitro experiments, an in vivo observational study documented the duration of meconium exposure (by change in the color of amniotic fluid from clear to meconium stained). This study showed that meconium was present in the majority of the placental tissues within 10 minutes from exposure and that there was no relationship between the duration of exposure to meconium and the extent and intensity of meconium uptake by macrophages in the placental membranes.253 We are not persuaded that examination of the placenta for meconium staining can lead to reliable inferences about the timing of fetal injury.

Placental inflammatory lesions associated with meconium exposure

A large body of evidence supports an association between inflammation and MSAF. Indeed, MSAF contains mediators such as IL-6,216 tumor necrosis factor alpha,217 IL-1β,217 IL-8,217 and phospholipase-A2,101 with inflammatory and/or chemotactic properties.196, 217, 254 Meconium can have a direct effect on the amnion. Indeed, incubation of amnion with meconium resulted in reactive amnion hyperplasia and cytoplasmic vacuolation after 1 hour of meconium exposure252 (Figure 12). Inflammatory lesions of the chorioamniotic membranes and umbilical cord are present in approximately 60% of cases of MSAF.197, 255, 256 Given that MSAF is associated with intra-amniotic infection in about 20% of cases, it is difficult to determine to what extent these lesions are attributable to MSAF or rather to intra-amniotic infection/inflammation. 255 257 256 162 Attempts have been made to identify specific placental lesions associated with meconium, such as necrosis of the chorionic plate and the muscular layer of the umbilical cord vessels258 197 (Figure 13). Moreover, meconium has been proposed to cause vasoconstriction of the umbilical cord vessels258 and cord vessel necrosis,197, 259 hence fetal distress or death.197

Figure 12.

Chorioamniotic membranes stained with H&E in a case of meconium stained amniotic fluid. Reactive amnion hyperplasia (red arrows) and cytoplasmic vacuolation (blue arrows) are observed.

Figure 13.

Meconium-induced umbilical cord vessel myonecrosis. 12A. Gross image of the umbilical cord in a case of fetal death with meconium stained amniotic fluid at term. Several areas of ulceration are observed. The Wharton’s jelly is eroded and the vessels are exposed. The dark color represents the muscularis of the vessels (12A). 12B. Shallower ulcerations of the cord. The muscularis is not eroded in this part of the cord. 12C. H&E staining of the umbilical cord. The umbilical vein is on the top and the two arteries below. At this magnification myonecrosis is not evident. 12D. The wall of the umbilical vein with evidence of myonecrosis. 12E. Umbilical artery with damaged myocytes (blue arrows) are observed in the muscular layer closer to the amniotic cavity. Cytoplasmic hypereosinophilia with nuclear pyknosis is evident. The red line indicates the outer perimeter of the umbilical vessel closer to the amniotic cavity, the red arrow indicates the umbilical cord artery lumen. 12F. Cytoplasmic and nuclear changes are better seen at higher magnification (blue arrows in Figure 12F).

Fetal defecation as a physiologic event

The traditional view has been that the fetus does not pass meconium in the absence of a pathologic process such as hypoxia or infection. However, an accumulating body of evidence suggests that defecation in utero is a physiologic phenomenon, and this is supported by the following observations: 1) when a non-hydrosoluble contrast media is administered via nasogastric tube in fetal goats, the contrast is subsequently detected in the amniotic fluid by serial radiographic examinations99 (Figure 14); 2) radioactive technetium 99 (99mTc-HIDA), injected intramuscularly in fetal rabbits, is detectable in the gastrointestinal tract and then in the amniotic cavity260 (Figure 15); and 3) closure of the fetal anus with a purse-string suture prevents the technetium from appearing in the amniotic fluid.261

Figure 14.

Evidence of in utero fetal defecation in goats by serial radiographic examinations. After intragastric injection via nasogastric tube, the non-hydrosoluble contrast medium persists in the stomach (red arrow) 4 hours after injection (Figure 13A). Evidence of contrast media in the small bowel (red arrow) 8 hours from injection is shown in figure 13B and eventually the contrast material is excreted in the amniotic cavity (red arrow) where it delineates the fetal body surface and fills the fetal airways. (Figure 13C). Reproduced with permission from Kizilcan et al99

Figure 15.

Results from an experimental study in rabbits performed to investigate the excretion of a radioactive substance (technetium 99, 99mTc-HIDA) injected into the fetal gluteus. The analysis of radioactivity of tissues from fetuses harvested at the rate of one per hour demonstrates that there is physiologic transit of radioactive meconium through the gastrointestinal tract (proximal bowel, mid bowel and distal bowel) into the amniotic fluid. The colored lines represent the magnitude of radioactivity in different tissues. Modified from Ciftci et al260

Detailed high-resolution ultrasound has shown defecation by the human fetus.262 López Ramón y Cajal and Ocampo Martinez evaluated fetal anal sphincter behavior in pregnancies between 15 and 41 weeks of gestation. Defecation was documented in all cases with the highest frequency between 28 and 34 weeks gestation262, 263 (Figure 16). Amniocentesis performed shortly after defecation in a subset of patients demonstrated clear amniotic fluid containing “whitish” material, which was consistent with bowel epithelium at microscopic examination264 (Figure 17). The passage of meconium has also been observed during fetoscopy in a case of stage III twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome at 19 weeks of gestation265 (Figure 18, Video 1 and 2). In this case, the stool was green in color, which could be attributed to the oxidative stress during the pathologic process.

Figure 16.

Evidence of fetal defecation with 4-Dimensional ultrasound. The anus was examined for 10–15 minutes. Courtesy of López Ramón y Cajal et al264

Figure 17.

Electron microscopic image of fetal cells found in the material from fetal defecation retrieved at amniocentesis. Structures are present on the cell surface that resemble primitive villi (boxed area). Reproduced with permission from López Ramón Y Cajal272

Figure 18.

Meconium debris in the amniotic cavity of twin B (recipient) during fetoscopy in a case of stage III twin to twin transfusion syndrome at 17 weeks. Courtesy of Dr Ramen Chmait.

Further evidence supporting that defecation occurs in utero derives from a study of 31 fetal autopsies, ranging from 14 to 27 weeks of gestation. The presence of green-colored meconium at different levels of the intestinal tract was detected in 28 cases and evidence of defecation, determined by the presence of meconium in the anus, was less frequent after 21 weeks gestation,266 which is the time the external anal sphincter becomes fully developed.267–269 These findings are consistent with the observation that the concentrations of intestinal enzymes (alkaline phosphatase and disaccharidases) in amniotic fluid peaked at 17 to 18 weeks of gestation, and decreased after 22 weeks.270, 271 Given that meconium contains colored pigment (eg, bilirubin) and that fetal defecation occurs throughout pregnancy,262 why MSAF occurs only in up to 20% of deliveries at term remains to be clarified.

Conclusion

MSAF occurs in up to 20% of term pregnancies and is a risk factor for adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. Hypoxia and/or intra-amniotic infection/inflammation can be found in a subset of patients. When meconium is present, continuous fetal heart rate electronic monitoring is indicated as a normal cardiotocographic tracing that effectively excludes fetal hypoxia. Assessment of intra-amniotic infection/inflammation can be performed by an analysis of amniotic fluid with a rapid point-of-care test for IL-6 or MMP-8. Antibiotic treatment of mothers with MSAF can reduce the rate of clinical chorioamnionitis. Defecation in utero is a physiologic phenomenon; however, hypoxia, intraamniotic infection/inflammation and post-term pregnancies are factors associated with MSAF. In the absence of these three factors, the etiology remains unknown. Omics analysis of amniotic fluid with meconium could help in the understanding of the pathophysiology of MSAF and to identify new biomarkers for risk stratification of patients according to the etiology of MSAF.

Supplementary Material

Video 1. Fetal defecation during fetoscopy in a case of stage III twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome at 19 weeks of gestation. Reproduced with permission from Solt et al265

Video 2. Meconium debris in the amniotic cavity of twin B (recipient) during fetoscopy in a case of stage III twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome at 17 weeks of gestation. Courtesy of Dr Ramen Chmait.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are very grateful to Dr Ramen H. Chmait, from the Department of Fetal Surgery, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles-USC Fetal-Maternal Center, Los Angeles, California, for providing images and a video of meconium debris in the amniotic cavity of twin B (recipient) during a fetoscopy procedure. Dr Chmait has no conflict of interest in relation to our expert review.

We also thank Julian Conde, MA, from the Perinatology Research Branch, Division of Obstetrics and Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services, Detroit, MI, for creating the figures and preparing the video of the article. Mr Conde has no conflict of interest in relation to our expert review.

The author (SJ) expresses profound personal gratitude to the Fernandez Foundation, Hyderabad, India, and its team Dr Pramod G, Dr Tejopratap, and Dr Asha for continued unrestrained benevolent administrative support; and to Dr Anupama Singh, Dr Nuzhat Aziz, and Dr Kasturi Sarvotham for perinatal autopsy referrals. The author (SJ) also dedicates this work to all of the families who have encountered a fetal or a neonatal loss.

FUNDING

This research was supported, in part, by the Perinatology Research Branch, Division of Obstetrics and Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (NICHD/NIH/DHHS); and, in part, with Federal funds from NICHD/NIH/DHHS under Contract No. HHSN275201300006C. Dr. Romero has contributed to this work as part of his official duties as an employee of the United States Federal Government.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.ROSS MG. Meconium aspiration syndrome--more than intrapartum meconium. The New England journal of medicine 2005;353:946–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GRAND RJ, WATKINS JB, TORTI FM. Development of the human gastrointestinal tract. A review. Gastroenterology 1976;70:790–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AHANYA SN, LAKSHMANAN J, MORGAN BL, ROSS MG. Meconium passage in utero: mechanisms, consequences, and management. Obstetrical & gynecological survey 2005;60:45–56; quiz 73–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ROSS WDJA The Works of Aristotle: Historia animalium, by Thompson DW. 1910. Clarendon Press;4;185. [Google Scholar]

- 5.BACK P WALTER K Developmental pattern of bile acid metabolism as revealed by bile acid analysis of meconium. Gastroenterology 1980;78:671–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DAVY J.On the composition of the meconium, and of the vernix caseosa, or lubricating matter of the new-born infant. Medico-chirurgical transactions 1844;27:189–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.BLUMENTHAL SG, IKEDA RM, RUEBNER BH. Bile pigments in humans and in nonhuman primates during the perinatal period: composition of meconium and gallbladder bile of newborns and adults. Pediatric research 1976;10:664–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.AZIZ S, LEROY PR, EGGERMONT E, FEVERY J. Bilirubin-IXbeta is a marker of meconium, like zinc coproporphyrin. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition 2001;32:287–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.GOURLEY GRB, AREND R.Excremental studies in human neonates. Identification of zinc coproporphyrin as a marker for meconium. Gastroenterology 1990;99:1705–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.HORIUCHI K, ADACHI K, FUJISE Y, et al. Isolation and characterization of zinc coproporphyrin I: a major fluorescent component in meconium. Clinical chemistry 1991;37:1173–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.USTA IM, SIBAI BM, MERCER BM, KREAMER BL, GOURLEY GR. Use of maternal plasma level of zinc-coproporphyrin in the prediction of intrauterine passage of meconium: a pilot study. The Journal of maternal-fetal medicine 2000;9:201–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NARITAKA N, SUZUKI M, SATO H, et al. Profile of bile acids in fetal gallbladder and meconium using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry 2015;446:76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.KIMURA A, YAMAKAWA R, USHIJIMA K, et al. Fetal bile acid metabolism during infancy: analysis of 1 beta-hydroxylated bile acids in urine, meconium and feces. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 1994;20:819–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.KUMAGAI MA, TAKEI H, et al. Perinatal bile acid metabolism: bile acid analysis of meconium of preterm and full-term infants. Journal of gastroenterology 2007;42:904–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.COLOMBO C, ZULIANI G, RONCHI M, BREIDENSTEIN J, SETCHELL KD. Biliary bile acid composition of the human fetus in early gestation. Pediatric research 1987;21:197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.BICHLER A, DAXENBICHLER G, GEIR W. Determination of amniotic fluid palmitic acid concentration for the estimation of fetal lung maturity. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry 1977;74:133–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.BLUMENTHAL SG, TAGGART DB, RASMUSSEN RD, et al. Conjugated and unconjugated bilirubins in humans and rhesus monkeys. Structural identity of bilirubins from biles and meconiums of newborn humans and rhesus monkeys. The Biochemical journal 1979;179:537–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MACIAS RIJJ, SERRANO MA. Excretion of biliary compounds during intrauterine life. World journal of gastroenterology 2009;15:817–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.BLUMENTHAL SGT, RASMUSSEN RD, et al. Changes in bilirubins in human prenatal development. The Biochemical journal 1980;186:693–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.PEREZ-MUÑOZ ME, ARRIETA MC, RAMER-TAIT AE, WALTER J. A critical assessment of the “sterile womb” and “in utero colonization” hypotheses: implications for research on the pioneer infant microbiome. Microbiome 2017;5:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.KENNEDY KMMJ, ADAM T, et al. Fetal meconium does not have a detectable microbiota before birth. Nature microbiology 2021;6:865–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.THEIS KRR, WINTERS AD, JOBE AH, GOMEZ-LOPEZ N. Lack of Evidence for Microbiota in the Placental and Fetal Tissues of Rhesus Macaques. mSphere 2020;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.THEIS KRR, GREENBERG JM, et al. No Consistent Evidence for Microbiota in Murine Placental and Fetal Tissues. mSphere 2020;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.VÖLTER C.Neueröffnete Hebammen-Schul: oder Nutzliche Unterweisung Christlicher Hebammen und Wehmüttern. Stuttgart; 1687; S153. [Google Scholar]

- 25.OHANA OG, SERGIENKO R, SHEINER E.Risk factors for intrauterine fetal death (1988–2009). The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet 2011;24:1079–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MANDELBAUM B.Gestational meconium in the high-risk pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology 1973;42:87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.BRAILOVSCHI YE, WIZNITZER A, SHAHAF P, LEVY A. Risk factors for intrapartum fetal death and trends over the years. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics 2012;285:323–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MALLOY MH. Chorioamnionitis: epidemiology of newborn management and outcome United States 2008. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association 2014;34:611–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ELLIS MN, MANANDHAR DS, COSTELLO AM. Risk factors for neonatal encephalopathy in Kathmandu, Nepal, a developing country: unmatched case-control study. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2000;320:1229–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.HAYES BC, MCGARVEY C, MULVANY S, et al. A case-control study of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in newborn infants at >36 weeks gestation. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2013;209:29.e1–29.e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.HAYES BCS, DONNELLY J, et al. The placenta in infants >36 weeks gestation with neonatal encephalopathy: a case control study. Archives of disease in childhood Fetal and neonatal edition 2013;98:F233–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.BERKUS MDO, SAMUELOFF A, XENAKIS EM, FIELD NT, RIDGWAY LE. Meconium-stained amniotic fluid: increased risk for adverse neonatal outcome. Obstetrics and gynecology 1994;84:115–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.KAYANGE N, KAMUGISHA E, MWIZAMHOLYA DL, JEREMIAH S, MSHANA SE. Predictors of positive blood culture and deaths among neonates with suspected neonatal sepsis in a tertiary hospital, Mwanza-Tanzania. BMC pediatrics 2010;10:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NATHAN L, LEVENO KJ, CARMODY TJ 3RD, KELLY MA, SHERMAN ML. Meconium: a 1990s perspective on an old obstetric hazard. Obstetrics and gynecology 1994;83:329–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DARGAVILLE PAB The epidemiology of meconium aspiration syndrome: incidence, risk factors, therapies, and outcome. Pediatrics 2006;117:1712–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DAVIS RO, PHILIPS JB 3RD, HARRIS BA JR., WILSON ER, HUDDLESTON JF. Fatal meconium aspiration syndrome occurring despite airway management considered appropriate. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1985;151:731–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.GREENOUGH A.Meconium aspiration syndrome--prevention and treatment. Early human development 1995;41:183–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.VAN IERLAND Y, DE BOER M, DE BEAUFORT AJ. Meconium-stained amniotic fluid: discharge vigorous newborns. Archives of disease in childhood Fetal and neonatal edition 2010;95:F69–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.HUTTON EKJ Consequences of meconium stained amniotic fluid: what does the evidence tell us? Early human development 2014;90:333–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.SPINILLO A, FAZZI E, CAPUZZO E, STRONATI M, PIAZZI G, FERRARI A.Meconium-stained amniotic fluid and risk for cerebral palsy in preterm infants. Obstetrics and gynecology 1997;90:519–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.REDLINE RW. Severe fetal placental vascular lesions in term infants with neurologic impairment. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2005;192:452–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.MCINTYRE S, TAITZ D, KEOGH J, GOLDSMITH S, BADAWI N, BLAIR E. A systematic review of risk factors for cerebral palsy in children born at term in developed countries. Developmental medicine and child neurology 2013;55:499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.NAEYE RL. Can meconium in the amniotic fluid injure the fetal brain? Obstetrics and gynecology 1995;86:720–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.OSTREA EM JR., NAQVI M. The influence of gestational age on the ability of the fetus to pass meconium in utero. Clinical implications. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica 1982;61:275–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.SEDAGHATIAN MRL, HOSSAIN MM, VIDYASAGAR D. Risk of meconium-stained amniotic fluid in different ethnic groups. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association 2000;20:257–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.SHAIKH EM, MEHMOOD S, SHAIKH MA. Neonatal outcome in meconium stained amniotic fluid-one year experience. JPMA The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 2010;60:711–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.FUJIKURA T, KLIONSKY B. The significance of meconium staining. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1975;121:45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MITRI F, HOFMEYR GJ, VAN GELDEREN CJ. Meconium during labour--self-medication and other associations. South African medical journal = Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde 1987;71:431–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MABINA MH, PITSOE SB, MOODLEY J. The effect of traditional herbal medicines on pregnancy outcome. The King Edward VIII Hospital experience. South African medical journal = Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde 1997;87:1008–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.BALCHIN I, WHITTAKER JC, LAMONT RF, STEER PJ. Maternal and fetal characteristics associated with meconium-stained amniotic fluid. Obstetrics and gynecology 2011;117:828–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.SCHULZE M.The significance of the passage of meconium during labor. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1925;10:83–88. [Google Scholar]

- 52.CAUGHEY AB, MUSCI TJ. Complications of term pregnancies beyond 37 weeks of gestation. Obstetrics and gynecology 2004;103:57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.BHAT R, VIDYASAGAR D. Delivery room management of meconium-stained infant. Clinics in perinatology 2012;39:817–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.RODRÍGUEZ FERNÁNDEZ V, LÓPEZ RAMÓN Y CAJAL C, MARÍN ORTIZ E, COUCEIRO NAVEIRA E. Intrapartum and perinatal results associated with different degrees of staining of meconium stained amniotic fluid. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology 2018;228:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.LEE J, ROMERO R, LEE KA, et al. Meconium aspiration syndrome: a role for fetal systemic inflammation. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2016;214:366.e1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.STEER PJ, EIGBE F, LISSAUER TJ, BEARD RW. Interrelationships among abnormal cardiotocograms in labor, meconium staining of the amniotic fluid, arterial cord blood pH, and Apgar scores. Obstetrics and gynecology 1989;74:715–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.MAZOR M, HERSHKOVITZ R, BASHIRI A, et al. Meconium stained amniotic fluid in preterm delivery is an independent risk factor for perinatal complications. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology 1998;81:9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.ROMERO R, HANAOKA S, MAZOR M, et al. Meconium-stained amniotic fluid: a risk factor for microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1991;164:859–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.MATTHEWS TG, WARSHAW JB. Relevance of the gestational age distribution of meconium passage in utero. Pediatrics 1979;64:30–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.KATZ VL, BOWES WA JR. Meconium aspiration syndrome: reflections on a murky subject. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1992;166:171–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.CLIFFORD SH. Postmaturity, with placental dysfunction; clinical syndrome and pathologic findings. The Journal of pediatrics 1954;44:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.BECKER RW, BARTH E, SCHULZ M. Fetal swallowing, gastro-intestinal activity and defecation in amnio. Surg Gynec Obstet 1940;70:603–14. [Google Scholar]

- 63.SPEERT H. Swallowing and gastrointestinal activity in the fetal monkey. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1943;45:69–82. [Google Scholar]

- 64.MCLAIN CR JR. AMNIOGRAPHY STUDIES OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL MOTILITY OF THE HUMAN FETUS. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1963;86:1079–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.ITOH Z. Motilin and clinical application. Peptides 1997;18:593–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.VANTRAPPEN G, JANSSENS J, PEETERS TL, BLOOM SR, CHRISTOFIDES ND, HELLEMANS J. Motilin and the interdigestive migrating motor complex in man. Digestive diseases and sciences 1979;24:497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.LUCAS A, CHRISTOFIDES ND, ADRIAN TE, BLOOM SR, AYNSLEY-GREEN A. Fetal distress, meconium, and motilin. Lancet (London, England) 1979;1:718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.MAHMOUD EL, BENIRSCHKE K, VAUCHER YE, POITRAS P. Motilin levels in term neonates who have passed meconium prior to birth. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition 1988;7:95–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.MEYDANLI MM, ENGIN-USTÜN Y, USTÜN Y, DENIZ D, TEMEL I, FIRAT S.Relationship between meconium staining, umbilical cord plasma motilin level and infantile colic. The Journal of reproductive medicine 2006;51:704–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.GOLDKRAND JW, SCHULTE RL, MESSER RH. Maternal and fetal plasma cortisol levels at parturition. Obstetrics and gynecology 1976;47:41–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.MALINOWSKA KW, HARDY RN, NATHANIELSZ PW. Plasma adrenocorticosteroid concentrations immediately after birth in the rat, rabbit and guinea-pig. Experientia 1972;28:1366–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.GILBERT WM, EBY-WILKENS E, PLOPPER C, WHITSETT JA, TARANTAL AF. Fetal monkey surfactants after intra-amniotic or maternal administration of betamethasone and thyroid hormone. Obstetrics and gynecology 2001;98:466–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.FLORIO P, ROMERO R, CHAIWORAPONGSA T, et al. Amniotic fluid and umbilical cord plasma corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), CRF-binding protein, adrenocorticotropin, and cortisol concentrations in intraamniotic infection and inflammation at term. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 2008;93:3604–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.PETRAGLIA F, AGUZZOLI L, FLORIO P, et al. Maternal plasma and placental immunoreactive corticotrophin-releasing factor concentrations in infection-associated term and pre-term delivery. Placenta 1995;16:157–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.MCLEAN M, BISITS A, DAVIES J, WOODS R, LOWRY P, SMITH R. A placental clock controlling the length of human pregnancy. Nature medicine 1995;1:460–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.YOU X, LIU J, XU C, et al. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) promotes inflammation in human pregnant myometrium: the evidence of CRH initiating parturition? The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 2014;99:E199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.TACHÉ YB. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptors and stress-related alterations of gut motor function. The Journal of clinical investigation 2007;117:33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.GRUNDY D, AL-CHAER ED, AZIZ Q, et al. Fundamentals of neurogastroenterology: basic science. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1391–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.HILLHOUSE EW, GRAMMATOPOULOS DK. The molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of the biological activity of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptors: implications for physiology and pathophysiology. Endocrine reviews 2006;27:260–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.LAKSHMANAN J, MAGEE TR, RICHARD JD, et al. Localization and gestation-dependent pattern of corticotrophin-releasing factor receptor subtypes in ovine fetal distal colon. Neurogastroenterology and motility : the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society 2008;20:1328–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.MAILLOT C, MILLION M, WEI JY, GAUTHIER A, TACHÉ Y. Peripheral corticotropin-releasing factor and stress-stimulated colonic motor activity involve type 1 receptor in rats. Gastroenterology 2000;119:1569–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.LAKSHMANAN J, OYACHI N, AHANYA SA, LIU G, MAZDAK M, ROSS MG. Corticotropin-releasing factor inhibition of sheep fetal colonic contractility: mechanisms to prevent meconium passage in utero. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2007;196:357.e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.STARKS GC. Correlation of meconium-stained amniotic fluid, early intrapartum fetal pH, and Apgar scores as predictors of perinatal outcome. Obstetrics and gynecology 1980;56:604–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.ZIADEH SM, SUNNA E. Obstetric and perinatal outcome of pregnancies with term labour and meconium-stained amniotic fluid. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics 2000;264:84–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.RICHEY SD, RAMIN SM, BAWDON RE, et al. Markers of acute and chronic asphyxia in infants with meconium-stained amniotic fluid. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1995;172:1212–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.JAZAYERI A, POLITZ L, TSIBRIS JC, QUEEN T, SPELLACY WN. Fetal erythropoietin levels in pregnancies complicated by meconium passage: does meconium suggest fetal hypoxia? American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2000;183:188–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.LAKSHMANAN J, AHANYA SN, REHAN V, OYACHI N, ROSS MG. Elevated plasma corticotrophin release factor levels and in utero meconium passage. Pediatric research 2007;61:176–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.BLACKWELL SC, MOLDENHAUER J, HASSAN SS, et al. Meconium aspiration syndrome in term neonates with normal acid-base status at delivery: is it different? American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2001;184:1422–5; discussion 25–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.DIJXHOORN MJ, VISSER GH, FIDLER VJ, TOUWEN BC, HUISJES HJ. Apgar score, meconium and acidaemia at birth in relation to neonatal neurological morbidity in term infants. British journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 1986;93:217–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.YEOMANS ER, GILSTRAP LC 3RD, LEVENO KJ, BURRIS JS. Meconium in the amniotic fluid and fetal acid-base status. Obstetrics and gynecology 1989;73:175–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.TRIMMER KJ, GILSTRAP LC 3RD. “Meconiumcrit” and birth asphyxia. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1991;165:1010–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.ANDRES RL, SAADE G, GILSTRAP LC, et al. Association between umbilical blood gas parameters and neonatal morbidity and death in neonates with pathologic fetal acidemia. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1999;181:867–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.RAMIN SM, GILSTRAP LC 3RD, LEVENO KJ, DAX JS, LITTLE BB. Acid-base significance of meconium discovered prior to labor. American journal of perinatology 1993;10:143–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.BROWN CA, DESMOND MM, LINDLEY JE, MOORE J. Meconium staining of the amniotic fluid; a marker of fetal hypoxia. Obstetrics and gynecology 1957;9:91–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.CIFTCI AO, TANYEL FC, BINGÖL-KOLOĞLU M, SAHIN S, BÜYÜKPAMUKÇU N. Fetal distress does not affect in utero defecation but does impair the clearance of amniotic fluid. Journal of pediatric surgery 1999;34:246–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.DEVANE GW, NADEN RP, PORTER JC, ROSENFELD CR. Mechanism of arginine vasopressin release in the sheep fetus. Pediatric research 1982;16:504–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.STARK RI, DANIEL SS, HUSAIN MK, SANOCKA UM, ZUBROW AB, JAMES LS. Vasopressin concentration in amniotic fluid as an index of fetal hypoxia: mechanism of release in sheep. Pediatric research 1984;18:552–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.WESTGATE JA, BENNET L, GUNN AJ. Meconium and fetal hypoxia: some experimental observations and clinical relevance. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2002;109:1171–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.KIZILCAN F, KARNAK I, TANYEL FC, BÜYÜKPAMUKÇU N, HIÇSÖNMEZ A. In utero defecation of the nondistressed fetus: a roentgen study in the goat. Journal of pediatric surgery 1994;29:1487–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.ROMERO R, YOON BH, CHAEMSAITHONG P, et al. Bacteria and endotoxin in meconium-stained amniotic fluid at term: could intra-amniotic infection cause meconium passage? The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet 2014;27:775–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.OMERO R, YOON BH, CHAEMSAITHONG P, et al. Secreted phospholipase A2 is increased in meconium-stained amniotic fluid of term gestations: potential implications for the genesis of meconium aspiration syndrome. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet 2014;27:975–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.MAZOR M, FURMAN B, WIZNITZER A, SHOHAM-VARDI I, COHEN J, GHEZZI F. Maternal and perinatal outcome of patients with preterm labor and meconium-stained amniotic fluid. Obstetrics and gynecology 1995;86:830–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.NACCASHA N, GERVASI MT, CHAIWORAPONGSA T, et al. Phenotypic and metabolic characteristics of monocytes and granulocytes in normal pregnancy and maternal infection. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2001;185:1118–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.FARIAS-JOFRE M, ROMERO R, GALAZ J, et al. Pregnancy tailors endotoxin-induced monocyte and neutrophil responses in the maternal circulation. Inflammation research : official journal of the European Histamine Research Society [et al] 2022;71:653–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.SEDLAK TW, SNYDER SH. Bilirubin benefits: cellular protection by a biliverdin reductase antioxidant cycle. Pediatrics 2004;113:1776–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.ABU-BAKAR A, ARTHUR DM, WIKMAN AS, et al. Metabolism of bilirubin by human cytochrome P450 2A6. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 2012;261:50–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.CLARK P, DUFF P. Inhibition of neutrophil oxidative burst and phagocytosis by meconium. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1995;173:1301–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.BRYAN C.Enhancement of bacterial infection by meconium. Johns Hopkins Medical Journal 1967;121:9-&. [Google Scholar]

- 109.FLORMAN AL, TEUBNER D. Enhancement of bacterial growth in amniotic fluid by meconium. The Journal of pediatrics 1969;74:111–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.BENACERRAF BR, GATTER MA, GINSBURGH F. Ultrasound diagnosis of meconium-stained amniotic fluid. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1984;149:570–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.WONG FW, LOONG EP, CHANG AM. Ultrasound diagnosis of meconium-stained amniotic fluid. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1985;152:359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.SEPÚLVEDA WH, QUIROZ VH. Sonographic detection of echogenic amniotic fluid and its clinical significance. Journal of perinatal medicine 1989;17:333–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.DEVORE GR, PLATT LD. Ultrasound appearance of particulate matter in amniotic cavity: vernix or meconium? Journal of clinical ultrasound : JCU 1986;14:229–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.BROWN DL, POLGER M, CLARK PK, BROMLEY BS, DOUBILET PM. Very echogenic amniotic fluid: ultrasonography-amniocentesis correlation. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine 1994;13:95–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.GIACOMELLO F.Sonographic findings of dense amniotic fluid. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1988;158:1242–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.KARAMUSTAFAOGLU BALCI B, GOYNUMER G. Incidence of echogenic amniotic fluid at term pregnancy and its association with meconium. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics 2018;297:915–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.GREEN JN, PAUL RH The value of amniocentesis in prolonged pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology 1978;51:293–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.ONCAGLIA N, ARREGHINI A, LOCATELLI A, BELLINI P, ANDREOTTI C, GHIDINI A. Obstetric cholestasis: outcome with active management. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology 2002;100:167–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.KNOX GE, HUDDLESTON JF, FLOWERS CE JR. Management of prolonged pregnancy: results of a prospective randomized trial. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1979;134:376–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.ARGYRIDIS S, ARULKUMARAN S. Meconium stained amniotic fluid. Obstetrics, Gynaecology & Reproductive Medicine 2016;26:227–30. [Google Scholar]

- 121.KITSOMMART R, THAMMAWONG N, SOMMAI K, YANGNOY J, BOWORNKITIWONG W, PAES B. Impact of meconium consistency on infant resuscitation and respiratory outcomes: a retrospective-cohort study and systematic review. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet 2021;34:4141–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.SHEINER E, HADAR A, SHOHAM-VARDI I, HALLAK M, KATZ M, MAZOR M. The effect of meconium on perinatal outcome: a prospective analysis. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet 2002;11:54–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.GLUCK O, KOVO M, TAIRY D, HERMAN HG, BAR J, WEINER E. The effect of meconium thickness level on neonatal outcome. Early human development 2020;142:104953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.ROSSI EM, PHILIPSON EH, WILLIAMS TG, KALHAN SC. Meconium aspiration syndrome: intrapartum and neonatal attributes. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1989;161:1106–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.LOCATELLI A, REGALIA AL, PATREGNANI C, RATTI M, TOSO L, GHIDINI A.Prognostic value of change in amniotic fluid color during labor. Fetal diagnosis and therapy 2005;20:5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.KHAZARDOOST S, HANTOUSHZADEH S, KHOOSHIDEH M, BORNA S. Risk factors for meconium aspiration in meconium stained amniotic fluid. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology : the journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2007;27:577–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.GREENWOOD C, LALCHANDANI S, MACQUILLAN K, SHEIL O, MURPHY J, IMPEY L.Meconium passed in labor: how reassuring is clear amniotic fluid? Obstetrics and gynecology 2003;102:89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.FAN HC, CHANG FW, PAN YR, et al. Approach to the Connection between Meconium Consistency and Adverse Neonatal Outcomes: A Retrospective Clinical Review and Prospective In Vitro Study. Children (Basel, Switzerland) 2021;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.FREY HA, TUULI MG, SHANKS AL, MACONES GA, CAHILL AG. Interpreting category II fetal heart rate tracings: does meconium matter? American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2014;211:644.e1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.MARTINEZ-BIARGE MJ, WUSTHOFF CJ, MERCURI E, COWAN FM. Antepartum and intrapartum factors preceding neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics 2013;132:e952–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.TRAN SH, CAUGHEY AB, MUSCI TJ. Meconium-stained amniotic fluid is associated with puerperal infections. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2003;189:746–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.WEN TS, ERIKSEN NL, BLANCO JD, GRAHAM JM, OSHIRO BT, PRIETO JA. Association of clinical intra-amniotic infection and meconium. American journal of perinatology 1993;10:438–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.MERCER LJ, BROWN LG, PETRES RE, MESSER RH. A survey of pregnancies complicated by decreased amniotic fluid. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1984;149:355–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.ASHWAL E, HIERSCH L, MELAMED N, AVIRAM A, WIZNITZER A, YOGEV Y.The association between isolated oligohydramnios at term and pregnancy outcome. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics 2014;290:875–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.MANNING FA, PLATT LD, SIPOS L.Antepartum fetal evaluation: development of a fetal biophysical profile. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1980;136:787–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.CAMPBELL S, WLADIMIROFF JW, DEWHURST CJ. The antenatal measurement of fetal urine production. The Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology of the British Commonwealth 1973;80:680–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.HOFMEYR GJ, XU H, EKE AC. Amnioinfusion for meconium-stained liquor in labour. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2014;2014:Cd000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 138.MACRI CJ, SCHRIMMER DB, LEUNG A, GREENSPOON JS, PAUL RH. Prophylactic amnioinfusion improves outcome of pregnancy complicated by thick meconium and oligohydramnios. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1992;167:117–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.SHERMAN DJ, ROSS MG, DAY L, HUMME J, ERVIN MG. Fetal swallowing: response to graded maternal hypoxemia. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md : 1985) 1991;71:1856–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.FUNAI EF, LABOWSKY AT, DREWES CE, KLIMAN HJ. Timing of fetal meconium absorption by amnionic macrophages. American journal of perinatology 2009;26:93–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.NAEYE RL. Functionally important disorders of the placenta, umbilical cord, and fetal membranes. Human pathology 1987;18:680–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.WEITZNER JS, STRASSNER HT, RAWLINS RG, MACK SR, ANDERSON RA JR., Objective assessment of meconium content of amniotic fluid. Obstetrics and gynecology 1990;76:1143–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.MOLCHO J, LEIBERMAN JR, HAGAY Z, HAGAY Y. Spectrophotometric determination of meconium concentration in amniotic fluid. Journal of biomedical engineering 1986;8:162–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.BENE BC. Diagnosis of meconium in amniotic fluids by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Physiological chemistry and physics 1980;12:241–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.BORCARD B, HILTBRAND E, MAGNIN P, et al. Estimating meconium (fetal feces) concentration in human amniotic fluid by nuclear magnetic resonance. Physiological chemistry and physics 1982;14:189–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.TUCKER AS, IZANT JRRJ Problems with meconium. American Journal of Roentgenology 1971;112:135–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.MANO N.Features and applications of bilirubin oxidases. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2012;96:301–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.BARANANO DE, RAO M, FERRIS CD, SNYDER SH. Biliverdin reductase: a major physiologic cytoprotectant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2002;99:16093–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.SVIGOS JMSF, PRIDMORE BR. Meconium-stained liquor at second trimester amniocentesis--is it significant? The Australian & New Zealand journal of obstetrics & gynaecology 1981;21:5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.ALLEN R.The significance of meconium in midtrimester genetic amniocentesis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1985;152:413–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.KARP LE, SCHILLER HS. Meconium staining of amniotic fluid at midtrimester amniocentesis. Obstetrics and gynecology 1977;50:47s–49s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]