Abstract

Glucose-6-phosphate translocase enzyme, encoded by SLC37A4 gene, is a crucial enzyme involved in transporting glucose-6-phosphate into the endoplasmic reticulum. Inhibition of this enzyme can cause Von-Gierke's/glycogen storage disease sub-type 1b. The current study dealt to elucidate the intermolecular interactions to assess the inhibitory activity of Chlorogenic acid (CGA) against SLC37A4 was assessed by molecular docking and dynamic simulation. The alpha folded model of SLC37A4 and CGA 3D structure were optimized using CHARMM force field, using energy minimization protocol in the Discovery Studio software. Glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) and CGA molecular docking, Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, analysis of binding free energy of G6P-SLC37A4 and CGA-SLC37A4 complexes was performed for 100 ns using GROMACS, followed by principal component analysis (PCA). The docking score of the CGA-SLC37A4 complex exhibited a higher docking score (– 8.2 kcal/mol) when compared to the G6P-SLC37A4 complex (– 6.5 kcal/mol), suggesting a stronger binding interaction between CGA and SLC37A4. Further, the MD simulation demonstrated a stable backbone and complex Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), the least RMS fluctuation, and stable active site residue interactions throughout the 100 ns production run. The CGA complex with SLC37A4 exhibits higher compactness and formed 8 hydrogen bonds to achieve stability. The binding free energy of the G6P-SLC37A4 and CGA-SLC37A4 complex was found to be – 12.73 and – 31.493 kcal/mol. Lys29 formed stable contact for both G6P (– 4.73 kJ/mol) and SLC37A4 (– 2.18 kJ/mol). This study imparts structural insights into the competitive inhibition of SLC37A4 by CGA. CGA shows potential as a candidate to induce manifestations of GSD1b by inhibiting glycogenolysis, and gluconeogenesis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-023-03661-5.

Keywords: Glycogen storage disease type 1, Glucose-6-phosphate exchanger, Chlorogenic acid, Molecular docking, Molecular dynamics, SLC37A4

Introduction

A group of genetic metabolic disorders known as the glycogen storage diseases (GSD) or glycogenoses is caused due to deficiency of the enzymes required to regulate glycogenolysis or gluconeogenesis (Chou et al. 2015). Hepatic GSD manifestations primarily include hypoglycemia, whereas muscular GSD manifests itself mostly through weakness and muscle spasms. These disorders affect about 1 in every 20,000–43,000 live births, and 80% of hepatic GSDs are Types I, III, and IX, of which GSD I is most prevalent (Özen 2007). The GSD I, also known as Von Gierke’s disease, is further categorized into type Ia and Ib. Reduced of complete inactivity of Glucose-6-phosphatase-α (G6Pase-α) causes GSDIa (Rake et al. 2002) and deficient activity of glucose-6-phosphate transporter (G6PT) or mutations in SLC37A4 gene, responsible for the production of G6PT causes GSDIb (Hiraiwa et al. 1999), (Bennett and Burchell 2013). SLC37A4, is responsible for transporting glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) from the cytoplasm into to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen. G6PT hydrolyses intraluminal G6P to Pi and glucose in a combination with either glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) or G6Pase. Fasting blood glucose levels are regulated by G6PT/G6Pase complex activity, whereas G6PT/G6Pase is necessary for neutrophil activities (Cappello et al. 2018). The incidence of GSD I is 1 in 100,000, 80% of the patients represent GSDIa and 20% by GSD Ib (Rake et al. 2002). Both disorders result in burdens such as hypoglycaemia, hypertriglyceridemia, hyperuricemia, lactic acidosis, and increased accumulation of glycogen primarily in the liver and kidneys lead to progressive hepatomegaly and nephromegaly (Parikh and Ahlawat 2021).

Along with the clinical manifestations and abnormalities reported in type Ia, neutropenia, persistent infections, and neutrophil dysfunction are specifically observed in type Ib (Calderwood et al. 2001) due to the impairment of glucose transportation across the cell membrane of the polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Long-term problems such as hepatic adenomas, inflammatory bowel disease, renal calculi, and progressive renal dysfunction, and hepatocellular cancer are all possible. (Franco et al. 2005) can develop in older children and adults (Dieckgraefe and Korzenik 2002).

The literature suggests that designing and establishing a disease model for GSD is an uphill task, though the gene knockout animals and genetically mutated cells serve as disease models. The stability, survivability, maintenance, and cost of these models are a big challenge. Based on the previous reports, The activity of G6PT transport is particularly and substantially hindered by a certain chemical derivatives like Chlorogenic acid (CGA), (Arion et al. 1997 and 1998); (Hemmerle et al. 1997) serving as a reversible inhibitor. Also, few chlorogenic acid derivatives, viz S3483 (Khan et al. 1998); (Leuzzi et al. 2003), and S4048 (Herling et al. 1999), are known to inhibit G6PT in diabetic subjects (Ong et al. 2013), this helped us to ideate that CGA can simulate the response or manifestations similar to GSD I.

Thus, this study is an attempt to comprehend the possible interactions and affinity of CGA towards SLC37A4 via chemoinformatics approaches viz., molecular docking and dynamics, and Molecular Mechanics Poisson−Boltzmann surface area (MMPBSA) calculations, which is further compared with the substrate docking, that CGA can be a suitable candidate to induce GSD I manifestations by inhibiting enzyme activity of G6PT.

Materials and methods

Protein and ligand preparation

The full-length SLC37A4 alpha folded model was downloaded from the alpha fold website (Jumper et al. 2021). The model structure having accession number AF-A0A1L1SUI3-F1-model_v2, organism: Mus musculus, was retrieved from the alpha fold website, and the Glucose-6-phosphate (PubChem CID: 5958) and CGA (PubChem CID: 1,794,427) 3D structure was from PubChem and optimized them using CHARMM (Chemical at Harvard Molecular Mechanics) force field using energy minimization protocol in the Discovery Studio Visualizer software version 2019.

Protein structure information

Amino acid distribution and quality assessment

To check the functional sites of the protein, the amino acid distribution of the obtained protein structure was assessed by the SAVES server. PROCHECK (Laskowski et al. 1993) was executed to acquire the data on the distribution of the amino acid Phi/Psi angles in the SLC37A4 and its overall quality was checked by ERRAT (Colovos and Yeates 1993). After molecular dynamic simulation, 0 ns and 100 ns frames for ligand bound complex were obtained and subjected to PROCHECK and ERRAT server. The data of protein alone and ligand bound form for both G6P and CGA were compared for amino acid distribution and overall quality.

Pocket information

P2Rank (Krivák and Hoksza 2018) server was utilized to find information of possible residues involved in the function of the protein and involved in the binding of ligand molecules. The pocket residues site possessing a higher probability score was considered for the docking study.

Molecular docking

The affinity of G6P and CGA towards the glucose-6-phosphate translocase was assessed by AutoDock vina and executed through the POAP pipeline (Samdani and Vetrivel 2018; Patil et al. 2022). During docking simulation, the grid box set to pocket 1 covering active site residues with center x = 0.435, y = 1.652, z = 2.037; sizes x = 46.89, y = 39.377, y = 41.626 were set with 1 Å spacing. The docking system exhaustiveness was set to 100. The intermolecular interactions between G6P and CGA in complex with SLC37A4 were examined through Discovery Studio Visualizer 2019v (Patil et al. 2020).

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

MD simulation for G6P-SLC37A4 and CGA-SLC37A4 complex were performed using Gromacs-2019.4 (Dwivedi et al. 2022) (Van Der Spoel et al. 2005). The complex topology was prepared by using the Amber ff99SB-ildn force field. A water simple point charge (SPCE) water model was used to solvate the complex structures in a cubic periodic box boundary condition of 10.0 Å. Subsequently the salt concentration of the complex systems was maintained at 0.15 M using a suitable number of Na+ and Cl− counter ions. Using an ensemble of NPT simulations for 100 ns, the final production run of each structure from the equilibration phase was carried out. An analysis of 100 ns trajectory was conducted using the packages in Gromacs. The root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), the radius of gyration (rGyr/Rg), and hydrogen bond (H-bond) contacts were considered for evaluation.

Binding free energy calculations

To analyse the binding free energy (ΔG binding) of an inhibitor with the protein across simulation time, the MM-PBSA technique was used and the binding free energy was estimated using the g mmpbsa function in GROMACS. (Kumari et al. 2014). In order to obtain an accurate result, we computed ΔG for the last 20 ns of the trajectory with dt 1000 frames and expressed the binding free energy in kcal/mol. Additionally, individual residue energy contributions in stable complex formation were also analysed (DasNandy et al. 2022).

Analysis of principal component

Principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to investigate the molecular motion using MD trajectories. The “least square fit” to the reference structure was used to eliminate the molecule’s translational and rotational motion. The covariance matrix obtained by a linear transformation of Cartesian coordinate space is diagonalized to provide a set of eigenvectors that exemplify the motion of the molecule. Where, the eigenvalue associated with each eigenvector indicates its energy contribution to the motion and also, projecting the trajectory onto an eigenvector illustrates the “time-dependent motions” that the parts do in a specific vibrational mode. The temporal average of the projection indicates the contribution of the atomic vibrational components to this type of coordinated motion. The eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the trajectory were generated by computing and diagonalizing the covariance matrix using the built-in gromacs utility “g covar.”. The “g anaeig” tool was also used to examine and illustrate the eigenvectors (Andrea Amadei et al. 1993); (Aalten et al. 1995); (Amadei et al. 1996); (Bhandare and Ramaswamy 2018); (Khanal et al. 2022); (Khanal et al. 2023). Over all, for analysing PCA, the least squares fit, g covar, a built-in feature of Gromacs, and g anaeig tools were employed.

Results and discussion

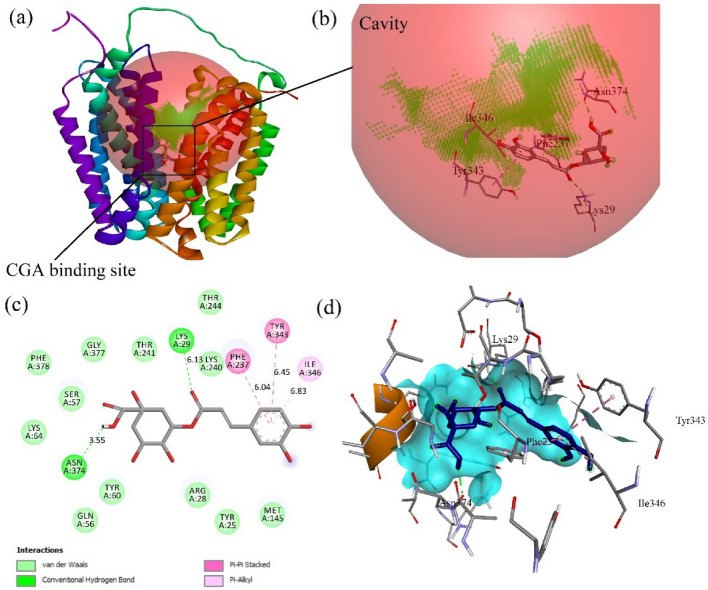

The current study intended to explore the intermolecular interactions and binding mode of chlorogenic acid (CGA) with the SLC37A4 target by assimilating the molecular docking and dynamics simulation. Previously, Interestingly, few in-vitro and experimental studies also support the inhibition of glucose-6-phosphate complex by CGA which corroborates our findings. CGA and its derivatives have been studied in diabetic conditions and even in normal conditions there are claims that CGA suppresses the hepatic blood glucose production by which the homeostatic regulation of blood glucose can be achieved (Hemmerle et al. 1997), (Arion et al. 1997). However, affinity with SLC37A4, precise binding site pockets, and inhibition of the activity of glucose-6-phosphatase complex are not been understood clearly. In this regard, rigid molecular docking was performed using AutoDock vina through the POAP pipeline to infer the possible interaction of chlorogenic acid with the SLC37A4 target. Recently, Veiga-da-Cunha et al. (2019) discovered that granulocytes from patients with defective SLC37A4 (G6PT) accumulate 1,5-anhydroglucitol-6-phosphate (1,5AG6P) that severely restrict/antagonize hexokinase function. The 1,5-anhydroglucitol is phosphorylated to produce the 1,5AG6P primarily (1,5AG),and hence the physiologic concentrations of 1,5AG produce extensive deposition of 1,5AG6P, a reduction in glucose utilization, and cell death in a model of G6PT-deficient mice neutrophils (Veiga-da-Cunha et al. 2019). Chlorogenic acid is well demonstrated as a specific, reversible inhibitor of SLC37A4 (Arion et al. 1998). A chlorogenic acid derivative (S3483), and G6PT inhibitor, were shown to impede G6P transport in differentiated promyelocytic HL-60 cells and microsomes derived from polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) in intact cells (Leuzzi et al. 2003). Interestingly, the PMN phenotype in GSD1b, a clinical illness in which the SLC37A4 protein is faulty or mutated, involves a reduction in numerous activities including chemotaxis, respiratory bursts, phagocytosis, and calcium signaling. Similarly, changes in numerous metabolic parameters – hexose uptake and transport, calcium mobilization, glucose phosphorylation, and have been proposed as probable causes for SLC37A4 functional abnormalities (Leuzzi et al. 2003), (Oguz et al. 2015). Hence, the interaction of chlorogenic acid and its derivatives with SLC37A4 and its inhibition will be a major contribution in causing GSD1b and chronic neutropenia via decreased glucose homeostasis, altered calcium permeability, apoptosis, and neutrophil chemotaxis. From the docking study, it is inferred that chlorogenic acid formed a hydrogen bond interaction with Asn374 and Lys29 and formed three non-hydrogen bonds with Phe237, Tyr343, and Ile346. The Lys29 and Phe237 were identified as active site residues and hence support the inhibition of SLC37A4. The substrate molecule Glucose-6-Phosphate (G6P) formed a hydrogen bond interaction with Lys29 and Ser57 (3.12Å) and formed one non-hydrogen bond with Asp245. This confirms that the CGA is a potent competitive inhibitor to SLC37A4. Lys29 residue was found to be the common hydrogen bond interactive residue for both G6P and CGA.

The MD simulation has become a very essential approach in reducing the limitation of computational prediction via inferring the stability of protein and ligand interactions in a desired physiological system (Yennamalli 2018). The molecular docking followed by dynamics gives deep insights into the behavior or structural changes information of ligands as well as its influence on protein stability upon binding (Du et al. 2016). Hence, the obtained data indicate concordance between computational prediction and experimental reports. In this study, a 100 ns MD production run was simulated to infer the structural changes upon ligand binding. The findings demonstrated that the RMSD of the protein was stabilized upon ligand interaction which was also inferred by the Rg value for both G6P and CGA. As it represents the compactness of complex formation in which ligand was found to get buried in the binding pocket during a 100 ns production run. In both the complexes, among the total residues, the longest loop region formed by Gly195 to Leu217 residues exhibited more fluctuation and was highly dynamic during MD simulation compared to other residues participating in the protein-ligand complex formation. Both G6P and CGA formed 8 H-bonds with SLC37A4 to form a stable complex in which 3 and 5 were consistent throughout the simulation, respectively. These computational hints provide deep insight into the structural changes of SLC37A4 upon ligand binding and offer essential evidence to corroborate the previous claims on chlorogenic acid as a potent competitive inhibitor of SLC37A4.

Protein information

The residue-by-residue geometry and overall structure geometry were studied by PROCHECK to check the stereochemical quality of a SLC37A4 protein structure (Fig. 1a). About 96.1% and 2.8% of the residues were found in the most favoured and additional allowed regions, respectively. Around 0.8% (3 residues) viz., Lys205, Lys207, and Glu213 were found in generously allowed regions in the Ramachandran plot. However, only 0.3% (one residue) i.e., Ser413 was found in the disallowed region. The overall quality of the protein structure was found to be 97.664%, by plotting the ERRAT plot which confirms the stability and represents the high resolution of the structure (Fig. 1b). In G6P- SLC37A4 0 ns frame complex, about 91.3%, and 8.2% residues were in the most favoured and additional allowed regions, respectively. One residue, Ser164 was found in the disallowed region (Figure S1). Whereas, in G6P- SLC37A4 100 ns frame complex, about 91.6% and 7.9% of the residues were found in the most favoured and additional allowed regions, respectively. One residue Thr364 was found in the generously allowed region and one residue, Ser164 was found in the disallowed region (Figure S2). All the active site residues involved in G6P binding were found to be in the most favoured region. The overall quality of the G6P- SLC37A4 0 ns and 100 ns frame complex was found to be 96.250% and 95.718%, respectively (Figures S3 and S4). In CGA- SLC37A4 0 ns frame complex, about 91.8%, and 7.9% residues were in the most favoured and additional allowed regions, respectively. One residue, Ser164 was found in the disallowed region (Figure S5). Whereas, in CGA- SLC37A4 100 ns frame complex, about 92.6% and 7.4% of the residues were found in the most favoured and additional allowed regions, respectively. No residues were found in the disallowed region (Figure S6). All the active site residues involved in CGA binding were found to be in the most favoured region. The overall quality of the G6P- SLC37A4 0 ns and 100 ns frame complex was found to be 99.75% and 97.805%, respectively (Figure S7 and Figure S8).

Fig. 1.

a Ramachandran plot of SLC37A4 structure (AF-A0A1L1SUI3-F1-model_v2) showed that 96.1% and 2.8% of the residues were found in most favoured and additional allowed regions, respectively. Around 0.8% (3 residues) viz., Lys205, Lys207, and Glu213. However, only 0.3% (one residue) i.e., Ser413 was found in disallowed region. b ERRAT plot showing error values for residues of the protein, the ERRAT values confirmed that overall quality of the protein structure was found to be 97.664%, c Ligand binding pocket of SLC37A4 showed that protein consists of 4 binding pockets in which pocket 1 was found to be the major binding pocket that scored the probability score of 0.879

The SLC37A4 protein comprises of 4 binding pockets in which pocket 1 (Fig. 1c) has residues number “21, 25, 28, 29, 56, 57, 60, 64, 114, 118, 139, 142, 143, 145, 146, 233, 237, 240, 241, 245, 274, 277, 278, 364, 367, 368, 391, 394, 395, 398” was found to be the major binding pocket that scored the probability score of 0.879 in P2Rank web server (Table 1).

Table 1.

The table explains major ligand binding pocket of SLC37A4 with its probability score and pocket residues

| Name | Probability | Sas points | Surf atoms | Pocket residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.879 | 163 | 78 | Tyr25, Arg28, Lys29, Gln56, Ser57, Tyr60, Lys64, Gln114, Trp118, Ala139, Ser142, Thr143, Met145, Asn146, Tyr21, Tyr233, Phe237, Lys240, Thr241, Asp245, Leu274, Ser277, Ile278, Tyr364, Ile367, Ala368, Gly391, Ala394, Asn395, Gly398 |

Molecular docking

G6P scored the lowest BE of – 6.5 kcal/mol via forming two H-bonds with Lys29 (4.62 Å) and Ser57 (3.12 Å) and formed one non-hydrogen bond with Asp245 (5.77 Å). Whereas, CGA scored the lowest BE of – 8.2 kcal/mol via forming two H-bonds with Asn374 (3.55 Å) and Lys29 (6.13 Å) and forming three non-hydrogen bonds with Phe237 (6.04 Å), Tyr343 (6.45 Å), and Ile346 (6.83 Å). Among these residues, Lys29 and Phe237 were identified as active site residues and Lys29 shared the common interacting residue for both G6P and CGA Figs. 2 and 3a–d shows the affinity of G6P and CGA with SLC37A4, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Demonstrates the Intermolecular interaction of G6P- SLC37A4 complex. a Demonstrates the G6P binding site within the SLC37A4 protein pocket. b Shows the magnified picture of (a) Affinity of G6P at ligand binding site, where CGA scored the lowest BE of – 6.5 kcal/mol via forming two H-bonds with Lys29 (4.62 Å) and Ser57 (3.12 Å) and formed one non-hydrogen bond with Asp245 (5.77 Å). c 2D picture characterizes the complex of G6P with SLC37A4 and its van der Waals, hydrogen bond, Pi- Pi and Pi-alkyl interaction. d Represents the ligand-fit site at SLC37A4 pocket 1

Fig. 3.

Demonstrates the Intermolecular interaction of CGA- SLC37A4 complex. a Demonstrates the CGA binding site within the SLC37A4 protein pocket. b Shows the magnified picture of (a) Affinity of CGA at ligand binding site, where CGA scored the lowest BE of − 8.2 kcal/mol via forming two H-bonds with Asn374 (3.55 Å) and Lys29 (6.13 Å), and forming three non-hydrogen bonds with Phe237 (6.04 Å), Tyr343 (6.45 Å), and Ile346 (6.83 Å). c 2D picture characterizes the complex of CGA with SLC37A4 and its van der Waals, hydrogen bond, Pi- Pi and Pi-alkyl interaction. d Represents the ligand-fit site at SLC37A4 pocket 1

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

MD simulations were performed for G6P-SLC37A4 and CGA-SLC37A4 complex for 100 ns production run and RMSD, RMSF, rGyr, H-bonds, and SASA were considered for evaluation.

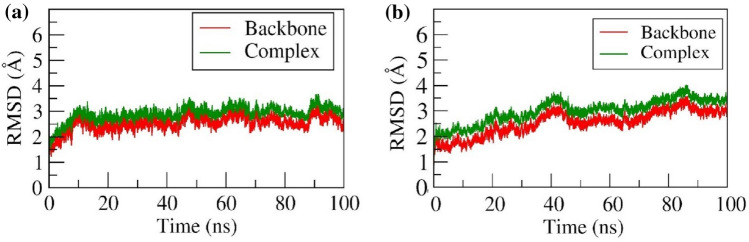

RMSD

This parameter can be used to determine whether the two confirmations differ from each other. The RMSD value is inversely proportional to the deviation. In the G6P-SLC37A4 complex, a slight increase in the RMSD was observed from ~ 1.5 Å to ~ 3 Å till 10 ns for both backbone and complex. After 10 ns, a stable RMSD and a similar trend were observed throughout the 100 ns simulation. Whereas, in the CGA-SLC37A4 complex, during the equilibration period, the backbone and complex RMSD were gradually increased from ~ 1.5 Å and ~ 1.8 Å to ~ 3.0 Å and ~ 3.5 Å, respectively till ~ 40 ns. Further, both backbone and complex RMSD were slightly decreased to ~ 2.5Åand ~ 3.0 Å, respectively till ~ 48 ns. Further, from ~ 48 ns to ~ 100 ns the RMSD was found to be stable with slight fluctuation at ~ 85 ns. The backbone and complex RMSD was confirmed to be stable, and formed a similar trend throughout the 100 ns production run. (Fig. 4a and b) represents the backbone and complex RMSD for G6P and CGA throughout 100 ns MD simulation, respectively.

Fig. 4.

RMSD of backbone atoms and complex of a G6P and b CGA with SLC37A4

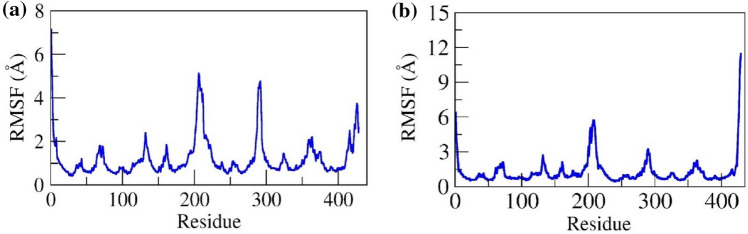

RMSF

RMSF analysis aids in order to understand which amino acids of the proteins are making more vibrations, that results in the destabilization of the protein, both in presence or in absence of the ligand molecule. In both the complexes, the longest flexible loop region i.e., residue Gly195 to Leu217 showed the maximum fluctuation (~ 6 Å). Further, the C-terminal loop region from Leu414 to Glu429 showed a maximum fluctuation up to 4 Å and 12 Å, respectively for G6P and CGA. A loop linker (residue Gly292 to Asn298) joining two helices showed a residual fluctuation up to ~ 6 Å and ~ 2 Å. However, residues involved in ligand binding (Lys29, Phe237, Tyr343, Ile346, and Asn374) showed the least fluctuation (< 1.5 Å) throughout 100 ns simulation in both complexes. The RMSF of Cα for G6P and CGA were depicted in Fig. 5a and b, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Represents Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) of Cα for a G6P-SLC37A4 and b CGA-SLC37A4 complexes

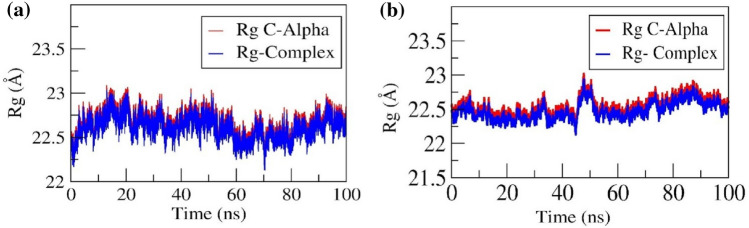

Radius of gyration (rGyr/Rg)

Compactness of the protein and ligand-bound form was determined by the radius of gyration. Folding and unfolding of the protein alone and in complex with G6P and CGA was analysed by the Rg values throughout 100 ns simulation. Both protein and complexes showed higher compactness throughout the 100 ns production period and formed a similar trend. In G6P- SLC37A4 complex, initially, the Rg value of protein and complex was 22.5 Å and gradually increased to 23 Å till 20 ns and again gradually decreased to 22.3 Å till 65 ns. Further, the Rg value increased to 22.6 Å till 100 ns. The sudden increase in the Rg value during the equilibration period indicates the opening of the pocket, which allows the ligand to get buried in the binding pocket, and the decrease in the Rg value after the equilibration period indicates the closing of the pocket, which allows ligand to form a stable complex (Movie 1). Similarly, in the CGA-SLC37A4 complex, the Rg value of protein and complex was 22.5 Å. After ~ 46 ns, the Rg value increased to ~ 22.8 Å and further decreased to ~ 22.6 Å and maintained the trend throughout the 100 ns run. The sudden increase in the Rg value after the equilibration period indicates the opening of the pocket, which allows the ligand to get buried in the binding pocket to form a stable complex (Movie 2). The Rg plots of protein and in complex with CGA were shown in Fig. 6a and b for G6P and CGA, respectively.

Fig. 6.

Radius of gyration (Rg) of Cα atoms of SLC37A4 in complex with a G6P and b CGA

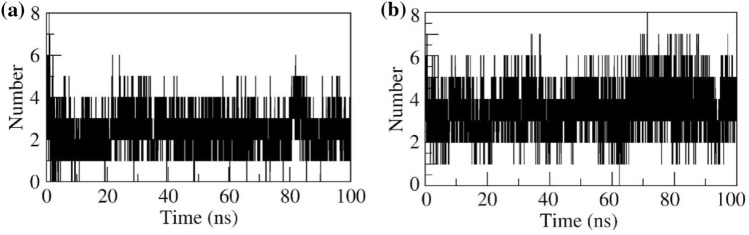

H-bond interactions

G6P in complex with SLC37A4 protein stabilized by forming 8 hydrogen bonds. Among them, 3 were consistent throughout the simulation. CGA in complex with SLC37A4 protein stabilized by the formation of 8 hydrogen bonds. Among them, 5 bonds were strong throughout the simulation. The H-bond contact of the G6P and CGA in complex with SLC37A4 was shown in Figs. 7a and b, respectively.

Fig. 7.

H-bonds formed between a G6P and b CGA with SLC37A4 throughout 100 ns MD simulation

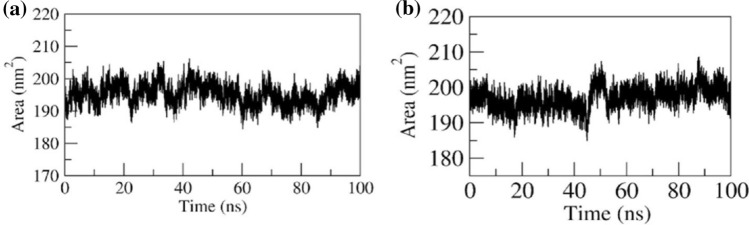

SASA

It is observed that the SLC37A4 protein comprises of 12 helices separated as a two-group with the longest loop formed by residues Gly195 to Leu217. The ligand-binding pocket (pocket 1) is present in between two group helices with a surface area of 163 nm2. In both complexes, the increased SASA after 44 ns (~ 190 nm2 to ~ 205nm2) was observed which is because of the flexible nature of the loop region and opening of the binding pocket. However, the surface area was found to be steady after ~ 55 ns (~ 197nm2). The initial and final surface area occupied by both docked complexes was ~ 199 nm2 and ~ 197 nm2. The average surface area occupied by the complex was ~ 197 nm2 (refer to Fig. 8a for G6P and Fig. 8b for CGA).

Fig. 8.

Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) of SLC37A4 in complex with a G6P and b CGA

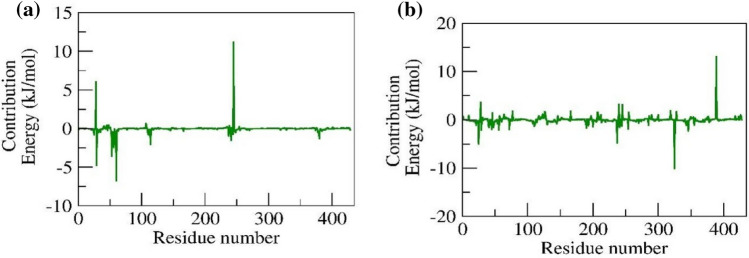

Binding free energy calculations and residual decomposition energy

The free energy required for the G6P and CGA to bind to the protein pocket was determined by MMPBSA. The binding free energy of G6P and CGA in complex with SLC37A4 was found to be – 12.72 ± 2.84 and – 31.493 ± 1.486 kcal/mol, respectively. The per residue energy contribution of the G6P- SLC37A4 complex revealed that the residues Lys29, Thr53, Gln56, Tyr60, Gln114, and Ala380 scored the least contribution energy of – 4.73, – 3.57, – 2.49, – 6.78, – 2.08, and – 1.33 kJ/mol, whereas, Arg28 and Asp245 scored the positive contribution energy of 6.07 and 11.18 kJ/mol. Similarly, the per residue energy contribution of the CGA- SLC37A4 complex revealed that the residues Lys29, Gln56, Phe237, Glu254, and Asp325 scored the least contribution energy of – 2.18, – 2.15, – 4.82, – 1.87, and – 10.09 kJ/mol, whereas, Arg28, Lys240, Asp245, Lys255, and Lys389 scored the positive contribution energy of 3.61, 3.18, 3.07, 1.54, and 13.08 kJ/mol. Figure 9a and b represents the per residue contribution for G6P and CGA in complex with SLC37A4.

Fig. 9.

Contribution energy plot demonstrate the significance of the ligand binding residues in stable complex formation a G6P and b CGA in complex with SLC37A4

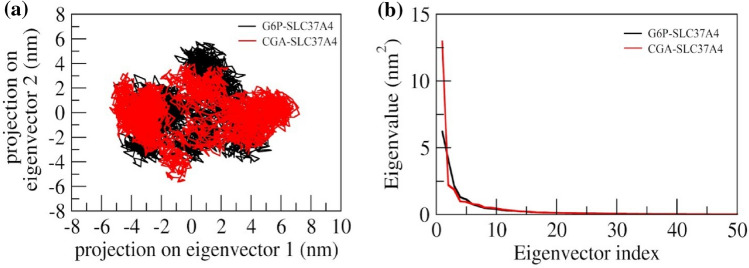

Principle component analysis

The collective motion sampled by the first two principal components (PCs) and 2D projections for PC1 and PC2 were plotted for G6P and CGA (Fig. 10a and b, respectively). The complex of G6P with SLC37A4 expresses the compact clusters in the conformational spaces those range from – 5 to 5.7 (Fig. 10a). In the MD trajectory of complex G6P with SLC37A4, PC1, and PC2 (top two modes) showed a constant distribution across the configurational space, in which CGA with SLC37A4 revealed little variation in the conformational space and was widely grouped in the range of – 5 to 7.8 (Fig. 10a). Further, it was observed that in CGA-SLC37A4 complex, during the simulation the maximum dynamics have been captured by the first 50 eigenvectors, of which the first three contributed substantially to the collective motions exerted by all the simulated complexes. The eigenvalue for the CGA complex was found to be higher compared to the G6P complex (Fig. 10b).

Fig. 10.

a Principal component analysis of protein–ligand complexes: the collective motion of G6P (black) and CGA (red) with SLC37A4 using projections of MD trajectories on two eigenvectors corresponding to the first two principal components. b The first 50 eigenvectors were plotted versus the eigenvalue for G6P (black) and CGA (red) with SLC37A4

Conclusion

The present study utilized chemoinformatics approaches viz., molecular docking, dynamics, and MM-PBSA calculation to decode the intermolecular interactions and binding affinity of Glucose 6 phosphate and chlorogenic acid against SLC37A4. The results reveal that chlorogenic acid forms a stable complex via interacting with active site residues Lys29 and Phe237 of SLC37A4 and exhibits its inhibitory activity. The SLC37A4 gene is responsible for synthesizing G6PT enzyme, Glucose-6-phosphate must be transported into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum by the G6PT enzyme, where it is hydrolysed into glucose and inorganic phosphate. Inhibition of G6PT would evidently lead to Von-Gierke’s/glycogen storage disease sub-type 1b, characterized by decrease in fasting blood glucose levels. A suitable G6PT inhibitor, would however be useful to researchers to manifest the disease model in research pertaining to Glycogen storage disease I. This study therefore aims to decipher the intermolecular interaction between Chlorogenic acid (an anticipated G6PT inhibitor) and G6PT enzyme by molecular docking and dynamic simulation studies. The current study is solely based on the computational approaches to assess the inhibitory interaction of CGA with the SLC37A4 gene. Thus, this study unwinds the scope for further experimental studies and validation of the GSD I model in experimental animals.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to express the help provided by the Principal of the Institution in carrying out the present work.

Funding

No funding was received from any funding institute for this study.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and supplementary files.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors approved the manuscript for publication.

References

- Amadei A, Linssen ABM, Berendsen HJ. Essential dynamics of proteins. Proteins. 1993;17(4):412–425. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadei A, Linssen AB, De GBL, Van Aalten DM, Berendsen HJ. An efficient method for sampling the essential subspace of proteins. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 1996;13(4):615–625. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1996.10508874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arion WJ, et al. Chlorogenic acid and hydroxynitrobenzaldehyde: new inhibitors of hepatic glucose 6-phosphatase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;339(2):315–322. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.9874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arion WJ, et al. Chlorogenic acid analogue S 3483: a potent competitive inhibitor of the hepatic and renal glucose-6-phosphatase systems. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998 doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett K, Burchell A. Brenner’s encyclopedia of genetics. 2. NY: Elsevier; 2013. Von Gierke disease; pp. 304–307. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandare VV, Ramaswamy A. The proteinopathy of D169G and K263E mutants at the RNA recognition motif (rrm) domain of tar DNA-binding protein (tdp43) causing neurological disorders: a computational study. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2018;36(4):1075–1093. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2017.1310670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood S, et al. Recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor therapy for patients with neutropenia and/or neutrophil dysfunction secondary to glycogen storage disease type 1b. Blood. 2001;97(2):376–382. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou JY, Jun HS, Mansfield BC. Type I glycogen storage diseases: disorders of the glucose-6-phosphatase/glucose-6-phosphate transporter complexes. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2015;38(3):511–519. doi: 10.1007/s10545-014-9772-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colovos C, Yeates TO. Verification of protein structures: patterns of nonbonded atomic interactions. Protein Sci. 1993;2(9):1511–1519. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DasNandy A, Patil VS, Hegde HV, Harish DR, Roy S. Elucidating type 2 diabetes mellitus risk factor by promoting lipid metabolism with gymnemagenin: an in vitro and in silico approach. Front Pharmacol. 2022 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1074342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieckgraefe BK, Korzenik ÆJR. Association of glycogen storage disease 1b and Crohn disease: results of a North American survey. Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161:S88–S92. doi: 10.1007/s00431-002-1011-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X, et al. Insights into protein–ligand interactions: mechanisms, models, and methods. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(2):1–34. doi: 10.3390/ijms17020144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi PSR, et al. System biology-based investigation of Silymarin to trace hepatoprotective effect. Comput Biol Med. 2022;142:105223. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco LM, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in glycogen storage disease type Ia: a case series. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2005;28(2):153–162. doi: 10.1007/s10545-005-7500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmerle H, et al. Chlorogenic acid and synthetic chlorogenic acid derivatives: novel inhibitors of hepatic glucose-6-phosphate translocase. J Med Chem. 1997;40(2):137–45. doi: 10.1021/jm9607360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraiwa H, et al. Inactivation of the glucose 6-phosphate transporter causes glycogen storage disease type 1b. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(9):5532–5536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumper J, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596(7873):583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanal P, Patil VS, Bhandare VV, Dwivedi PS, Shastry CS, Patil BM, et al. Computational investigation of benzalacetophenone derivatives against SARS-CoV-2 as potential multi-target bioactive compounds. Comput Biol Med. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanal P, Patil VS, Bhandare VV, Patil PP, Patil BM, Dwivedi PS, Bhattacharya K, Harish DR, Roy S. Systems and in vitro pharmacology profiling of diosgenin against breast cancer. Front Pharmacol. 2023;13:1052849. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1052849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivák R, Hoksza D. P2Rank: machine learning based tool for rapid and accurate prediction of ligand binding sites from protein structure. J Cheminformatics. 2018;10(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13321-018-0285-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari R, Kumar R, Lynn A. G-mmpbsa -A GROMACS tool for high-throughput MM-PBSA calculations. J Chem Inf Model. 2014;54(7):1951–1962. doi: 10.1021/ci500020m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, et al. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26(2):283–291. doi: 10.1107/s0021889892009944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leuzzi R, et al. Inhibition of microsomal glucose-6-phosphate transport in human neutrophils results in apoptosis: a potential explanation for neutrophil dysfunction in glycogen storage disease type 1b. Blood. 2003;101(6):2381–2387. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oguz MM, et al. Glycogen storage disease type 1B: An early onset severe phenotype associated with a novel mutation (IVS4) in the glucose 6-phosphate translocase (SLC37A4) gene in a Turkish patient. Genetic Couns. 2015;25(4):389–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong KW, Hsu A, Tan BKH. Anti-diabetic and anti-lipidemic effects of chlorogenic acid are mediated by ampk activation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85(9):1341–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özen H. ‘Glycogen storage diseases: new perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(18):2541–2553. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i18.2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh NS, Ahlawat R (2021) Glycogen storage disease type I, StatPearls. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534196/. Accessed 9 Oct 2022 [PubMed]

- Patil VS, Deshpande SH, Harish DR, Patil AS, Virge R, Nandy S, Roy S. Gene set enrichment analysis, network pharmacology and in silico docking approach to understand the molecular mechanism of traditional medicines for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. J Proteins Proteom. 2020;11:297–310. doi: 10.1007/s42485-020-00049-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patil VS, Harish DR, Vetrivel U, Deshpande SH, Khanal P, Hegde HV, et al. Pharmacoinformatics analysis reveals flavonoids and diterpenoids from Andrographis paniculata and Thespesia populnea to target hepatocellular carcinoma induced by hepatitis B virus. Appl Sci. 2022;12(21):10691. doi: 10.3390/app122110691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rake J, et al. Glycogen storage disease type I: diagnosis, management, clinical course and outcome. Results of the European study on glycogen storage disease type I (ESGSD I) Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161:S20–S34. doi: 10.1007/s00431-002-0999-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samdani A, Vetrivel U. POAP: a GNU parallel based multithreaded pipeline of open babel and AutoDock suite for boosted high throughput virtual screening. Comput Biol Chem. 2018;74:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Aalten DMF, Findlay JBC, Amadei A, Berendsen HJC. Essential dynamics of the cellular retinol-binding protein evidence for ligand-induced conformational changes. Protein Eng. 1995;8(11):1129–1135. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.11.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Spoel D, et al. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J Comput Chem. 2005;26(16):1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga-da-Cunha M, et al. Failure to eliminate a phosphorylated glucose analog leads to neutropenia in patients with G6PT and G6PC3 deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(4):1241–1250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1816143116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yennamalli RM. Protein design. Encycl Bioinform Comput Biol: ABC Bioinform. 2018;1–3(1):644–651. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-809633-8.20151-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and supplementary files.