Abstract

Suspended Sediment transport in the Northern Waters of Aceh is investigated in the domains between 5.4° - 5.65° N Latitude and 95.15° - 95.45° E. Therefore, this study aims to calculate the suspended sediment transport using a non-hydrostatic hydrodynamic model with an output distribution of total suspended sediment concentration. The model was run using tidal components of M2, S2, K1, O1, N2, K2, P1, Q1 and the wind every 6 h in February and August 2019 representing the North East and South West monsoons, as well as sea temperature and salinity data. The results of the model correlated with the Tide Model Driver data obtained, and the simulation results indicated the current in February 2019 is different than in August. The numerical simulation results show that the distribution of suspended sediments in Northern Waters of Aceh is driven by currents. Furthermore, the hydrodynamics and the designed model showed that the distribution value of the surface total suspended sediment concentration was lower in August than in February 2019. The verification results of the surface total suspended sediment concentration between the model and the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite showed a good match. These results can facilitate the analysis of limited observation and remote sensing data.

Keywords: Tidal harmonic component constant, Current circulation, Total suspended sediment concentration, Northern Waters of Aceh

Highlights

-

•

The tidal amplitude is smaller in the West than in the North of Northern Waters of Aceh.

-

•

Currents in February differ from August 2019 due to winds.

-

•

Total suspended solid concentrations are higher in the North than in the West of Northern Waters of Aceh.

-

•

Surface currents determine the distribution of total suspended solid.

1. Introduction

Northern Waters of Aceh (NWA) is located on Sumatra Island at 5.4° N- 5.65°N and 95.15°E - 95.45°E, directly adjacent to the Malacca Strait and the eastern Indian Ocean. Therefore, it makes NWA a potential area for capturing fisheries, tourism, and shipping activities, as well as ports and offshore development area [1].

Anthropogenic activities generally increase the turbidity of the water column as well as sedimentation in river channels, estuaries, and harbours [2,3]. This sediment accumulation affects water management, flood control, and the production of energy. In reservoir water, sedimentation reduces the storage capacity, while in ports, it causes silting of the port pool. Increased turbidity also affects the transport of nutrients and contaminants adsorbed to the clay particles. This decline in environmental quality continues to occur along with increasing natural pressure and anthropogenic activities [4,5].

Fine-grained sediments are formed under low energy conditions, they can provide an overview of sea level changes and record phenomena such as remnants of volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, and tropical cyclones. These sediments are part of the reconstruction of coastal processes, formed from weathered wood, rocks, microfossils, diatoms, and foraminifera, which accumulate in coastal or estuaries. Moreover, fine-grained sediments generally originate from the incoming sediment load of a river and are carried to estuaries as well as coasts [5]. This process of sediment transport is influenced by the river discharge, wind, waves, tides, and other disturbances in the sea column [6].

Based on the Lagrangian model simulation, Putri and Pohlmann [7] showed that particle dispersion is quite complex and is influenced by seasonal hydrodynamics. In the Malacca Strait and Siak River, although the main current circulation consistently moves to the north of the Malacca Strait, pollutants move seasonally along with the monsoon [[8], [9], [10]]. On the other hand, the hydrodynamics of currents accelerates the erosion process on the beach, indicating that sediment movement is dependent on currents [4,11].

Research on the effect of hydrodynamics on suspended sediments in the NWA is still limited. This is because measurements at sea are quite difficult and information on suspended sediments is known from the analysis of cloud-covered satellite images. So far there is no model that can describe the dynamics of sediment suspension in the NWA.

According to previous studies, tides and monsoons are important for hydrodynamics in NWA. The semidiurnal tides from the Indian Ocean and the monsoon that drives the seasonal wind cause hydrodynamics in NWA to be complex [[12], [13], [14], [15]]. These hydrodynamic factors can improve the dynamics of tracer dispersions, especially suspended sediments in the NWA.

In this study, suspended sediment transport was studied by simulating a three-dimensional non-hydrostatic model. Suspended sediments are assumed to be non-buoyancy tracers with uniform sizes and the speed of sediment falling depends on ocean currents. Preliminary information on suspended sediments was obtained from turbidity analysis of the kd490 Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) [[16], [17], [18]]. The kd490 data is a good indicator for assessing turbidity in inshore and shallow waters [17,[19], [20], [21]]. Likewise the empirical formula used [17], is accurate and realistic for shallow waters as previously demonstrated in the Chesapeake Bay.

The non-hydrostatic model was previously used by Rizal et al. [22] and Rizal et al. [23] in a preliminary study of internal and Lee waves. Furthermore, Haditiar et al. [15] used a three-dimensional non-hydrostatic model for the study of tidal wave propagation in the Malacca Strait and the South China Sea. This model was also used by Ikhwan et al. [24] in assessing the energy potential of tidal turbines in the Western Waters of Aceh (WWA). The prediction results of the hydrodynamics of currents with the non-hydrostatic model are quite good because it considers the vertical momentum and non-hydrostatic pressure differently from the hydrostatic approach or the sea model in general. Hence, this model is expected to be relatively good to high-resolution models such as in NWA.

This paper model suspended sediment transport using the advection-diffusion equation in the NWA. Previous research related to the sediment transport model also used the advection-diffusion equation, namely the surface suspended sediment modeling in Hangzhou Bay by Du et al. [2], but without the considering wind. In addition, Chen et al. [25] also investigated the suspended sediment transport model in the main Danshui-River estuary, but only tidal estuaries act as sediment drivers. The novelty of this research is suspended sediment transport with non-hydrostatic hydrodynamics considering wind, temperature, salinity, and tides.

This study presents three parts: first, hydrodynamics in NWA along with the analysis obtained from three-dimensional simulations of wind, temperature, salinity, and tides. Second, the concentration of suspended sediment was obtained from turbidity analysis from the kd490 Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS). Third, the dynamics of suspended sediments based on hydrodynamic conditions are verified again with the image results. So the purpose of this study is to map the distribution of total suspended sediment concentrations in the NWA.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data

2.1.1. Model input

The input model for the non-hydrostatic ocean model simulation requires initials and open boundary values. Bathymetry initials were obtained from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission or SRTM [26,27], while temperature and salinity were obtained from Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service (CMEMS). The open boundary values consist of sea tides and winds. The tidal force consists of the tidal constants of the M2, S2, K1, O1, N2, K2, P1, and Q1 components, namely the amplitude, and the phase obtained from http://polaris.esr.org/ptm_index.html which was previously developed by Egbert and Erofeeva [28]. The wind was determined every 6 h in February and August 2019 representing the North East and South West monsoons. Wind data were derived from The National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) [29]. For verification, the sea level obtained from the non-hydrostatic model is analyzed using the least square method [[30], [31], [32], [33]] and then compared with tidal amplitude and phase components of the Tide Model Driver (TMD) [10,34].

2.1.2. The initial for suspended sediment

Suspended sediments are characterized by turbidity in the water or color spectrum. Kd490 was obtained from VIIRS data as an indicator of water turbidity [18,35]. The TSS concentration value was calculated based on the relationship with kd490 which is shown in equation (1).

| (1) |

with kd490 in m−1 [17].

The TSS concentrations obtained from the monthly Kd490 analysis, namely February and August 2019, were input into the non-hydrostatic ocean model simulation. The results of the TSS distribution from the next model were compared again with the daily VIIRS data including February 5, 12, 19, and 26 2019, while those of August 6, 13, and 20.

2.2. The set equation of the non-hydrostatic model

The marine hydrodynamics and sediment transport equations consist of one complete Navier-Stokes equation [[36], [37], [38], [39]]. In the non-hydrostatic model, the dynamic pressure equation is separated into two parts (equations (2), (3))):

| (2) |

| (3) |

where p refers to the hydrostatic pressure field with reference to the intrusive (horizontal) sea level and q is the pressure effect exerted by the inclined sea level and by non-hydrostatic pressure.

Next, the momentum equation (equation (4)) is written as:

| (4) |

where (u, v, w) is the velocity component in Cartesian coordinates (x, y, z), t is time, f is the Coriolis parameter, and ρ0, ρ are the reference and the actual density.

| (5) |

| (6) |

The subject property for advection is defined by equation (5) and the diffusion of the three velocity components is calculated by equation (6). and are the coefficients of eddy friction or horizontal and vertical eddies, respectively.

Furthermore, the continuity equation (equation (7)) for a compressed fluid is as follows:

| (7) |

The prognostic equation for the surface dynamic stress is determined by the vertical integration of the continuity equation (equation (8)):

| (8) |

Where qs = ρ0gη where ρ0 is the surface density and is η the sea level, h is the total local water depth, and <.> is the vertical mean notation.

The density conservation equation (equation (9)) is:

| (9) |

with ,

where and are the horizontal and vertical eddy or eddy diffusion.

The advection equation (equation (10)) of arbitrary parameter B is written as follows:

| (10) |

Furthermore, the equation is solved using the Arakawa C-grid semi-implicit finite difference numerical method, with the input data for tidal boundary conditions at open boundaries according to the domain shown in Fig. 1 with wind scenarios for February and August 2019 (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). The wind was determined every 6 h in February and August 2019 representing the North East and South West monsoons. Wind data were derived from The National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP). The model also provided sea temperature and sea salinity data as initials for the calculation of Density . The spatial interval used was , while vertically was used with 24 layers to a depth of 240 m, and the time interval which meets the Courant-Friedrichs Lewy (CFL) criteria, . Horizontal viscosity and diffusivity coefficient , vertical viscosity and diffusivity coefficient follows equation (11) and bottom friction factor , when ; , when , and , when [40]. The vertical viscosity and diffusivity coefficient [15,39,41] is written as follows:

| (11) |

where and are the viscosity and diffusivity coefficients in the vertical direction, and the Brunt-Väisälä frequency () is based on density stratification.

Fig. 1.

Research location with bathymetry in meters. Bathymetry data is obtained from Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) 15 arcseconds (Jarvis et al., 2008; Tozer et al., 2019).

Fig. 2.

Wind vector in February 2019 (m/s). Wind data is derived from NCEP (https://downloads.psl.noaa.gov/Datasets/ncep.reanalysis/surface_gauss/uwnd.10m.gauss.2019.nc).

Fig. 3.

Wind vector in August 2019 (m/s). Wind data is derived from NCEP (https://downloads.psl.noaa.gov/Datasets/ncep.reanalysis/surface_gauss/vwnd.10m.gauss.2019.nc).

The sea level obtained from changes in non-hydrostatic pressure with respect to time (equation (8)) is analyzed using the least square method to obtain the amplitude and phase of the tides in the NWA.

2.3. Sediment transport equation

The distribution of sediment concentration equation () for suspended sediment transport is:

| (12) |

where represents the TSS concentration and the other variables ( display the same variables as the non-hydrostatic model set [25,35]. The TSS in this study is assumed to be based on the TSS analysis research method from remote sensing imagery. In this study, suspended sediments are non-buoyancy particles with a very fine size so that the weight of the fall is very small and can be simplified. Under these conditions, the vertical momentum of the non-hydrostatic current plays an important role in the vertical movement of suspended sediments.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Amplitude and phase

Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7 show the amplitude and phase of the semidiurnal tide components M2 and S2, while Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10, Fig. 11 depict the diurnal tide components K1 and O1. The tidal amplitude and phase M2, S2, K1, O1 contribute as one of the driving forces of the current.

Fig. 4.

Amplitude of M2-tide (cm).

Fig. 5.

Phase of M2-tide (°).

Fig. 6.

Amplitude of S2-tide (cm).

Fig. 7.

Phase of S2-tide (°).

Fig. 8.

Amplitude of K1-tide (cm).

Fig. 9.

Phase of K1-tide (°).

Fig. 10.

Amplitude of O1-tide (cm).

Fig. 11.

Phase of O1-tide (°).

Fig. 4 shows the M2-tidal amplitude between 27 cm and 37 cm which increases from South to North on the West side of the NWA and between 35 cm and 40 cm rising from West to East on the North side. Furthermore, Fig. 5 shows the M2-tidal phase between 74° and 91°, while Fig. 6 presents the S2-tidal amplitude between 14 cm and 18 cm which increases from South to North on the West side and between 18 cm and 20 cm from West to East on the North side. Fig. 7 shows the S2-tidal phase between 117° and 135°.

Fig. 8 shows the K1-tidal amplitude between 9.2 cm and 9.7 cm, while Fig. 9 demonstrates the K1-tidal phase between 224° and 229°. Also, Fig. 10 shows the O1-tidal amplitude between 4.4 cm and 4.5 cm, while Fig. 11 depicts the O1-tidal phase between 179° and 185°.

Table 1, Table 2 show the amplitude and phase components of M2, S2, K1, O1, N2, K2, P1, Q1 for 4 stations. The four (4) stations consist of Lhoknga, Ulee Lheue, Lampulo, and Alue Naga. Based on Table 1, the amplitude of M2, S2 ranged from 0.29 m to 0.41 m; 0.10 m–0.14 m, while that of K1, O1 ranged from 0.11 m to 0.12 m; 0.04 m. The Amplitude components of N2, K2, P1, and Q1 were 0.05 m–0.07 m; 0.001 m–0.002 m; 0.003 m–0.004 m and 0.007 m respectively. Based on Table 2, phases M2, S2 ranged from 76° to 84°; 113°–127° while phase K1, O1 ranged from 216° to 220°; 179°–184°. Meanwhile, the component phases N2, K2, P1, Q1 were 60°–73°, respectively; 138°–148°; 206°–210° and 121°–125°.

Table 1.

Tidal amplitude of M2, S2, K1, O1, N2, K2, P1, Q1 components.

| Station | Latitude (°N) | Longitude (°E) | AM2(m) |

AS2(m) |

AK1(m) |

AO1(m) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | TMD | Model | TMD | Model | TMD | Model | TMD | |||

| Lhoknga | 5.4750 | 95.2292 | 0.2879 | 0.3080 | 0.1287 | 0.1387 | 0.0881 | 0.0949 | 0.0411 | 0.0421 |

| Ulee Lheue | 5.5792 | 95.2833 | 0.3882 | 0.3639 | 0.1716 | 0.1627 | 0.0909 | 0.0977 | 0.0412 | 0.0424 |

| Lampulo | 5.6083 | 95.3292 | 0.3929 | 0.3817 | 0.1738 | 0.1698 | 0.0914 | 0.0986 | 0.0414 | 0.0425 |

| Alue Naga |

5.6250 |

95.3542 |

0.4033 |

0.3953 |

0.1787 |

0.1756 |

0.0924 |

0.0993 |

0.0415 |

0.0426 |

| Station |

Latitude (°N) |

Longitude (°E) |

AN2(m) | AK2(m) | AP1(m) | AQ1(m) | ||||

| Model |

TMD |

Model |

TMD |

Model |

TMD |

Model |

TMD |

|||

| Lhoknga | 5.4750 | 95.2292 | 0.0530 | 0.0553 | 0.0023 | 0.0400 | 0.0030 | 0.0286 | 0.0054 | 0.0061 |

| Ulee Lheue | 5.5792 | 95.2833 | 0.0662 | 0.0634 | 0.0031 | 0.0463 | 0.0031 | 0.0295 | 0.0051 | 0.0060 |

| Lampulo | 5.6083 | 95.3292 | 0.0670 | 0.0660 | 0.0031 | 0.0484 | 0.0031 | 0.0298 | 0.0051 | 0.0060 |

| Alue Naga | 5.6250 | 95.3542 | 0.0688 | 0.0682 | 0.0032 | 0.0500 | 0.0031 | 0.0301 | 0.0052 | 0.0059 |

Table 2.

Tidal phase of M2, S2, K1, O1, N2, K2, P1, Q1 components.

| Station | Latitude (°N) | Longitude (°E) | φM2(°) |

φS2(°) |

φK1(°) |

φO1(°) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | TMD | Model | TMD | Model | TMD | Model | TMD | |||

| Lhoknga | 5.4750 | 95.2292 | 75.78 | 82.26 | 115.80 | 106.78 | 224.05 | 208.80 | 176.54 | 178.98 |

| Ulee Lheue | 5.5792 | 95.2833 | 83.54 | 84.72 | 128.69 | 113.02 | 228.90 | 211.24 | 181.08 | 180.90 |

| Lampulo | 5.6083 | 95.3292 | 83.59 | 84.89 | 128.88 | 114.44 | 228.92 | 211.94 | 181.00 | 181.43 |

| Alue Naga |

5.6250 |

95.3542 |

83.68 |

85.07 |

129.34 |

115.42 |

228.99 |

212.44 |

180.75 |

181.80 |

| Station |

Latitude (°N) |

Longitude (°E) |

φN2(°) | φK2(°) | φP1(°) | φQ1(°) | ||||

| Model |

TMD |

Model |

TMD |

Model |

TMD |

Model |

TMD |

|||

| Lhoknga | 5.4750 | 95.2292 | 62.51 | 65.76 | 56.00 | 98.23 | 222.62 | 206.37 | 110.40 | 125.20 |

| Ulee Lheue | 5.5792 | 95.2833 | 75.52 | 72.34 | 67.10 | 104.76 | 227.89 | 209.06 | 109.14 | 125.66 |

| Lampulo | 5.6083 | 95.3292 | 75.78 | 73.98 | 67.71 | 106.39 | 227.51 | 209.81 | 109.33 | 125.84 |

| Alue Naga | 5.6250 | 95.3542 | 76.31 | 75.11 | 69.22 | 107.52 | 227.47 | 210.34 | 108.86 | 125.99 |

The values of each Lhoknga's amplitude and phase were smaller than those of Ulee Lheue, Lampulo, and Alue Naga. The amplitude and phase of the Lhoknga station are influenced by the Indian Ocean and the Ulee Lheue, while Lampulo and Alue Naga stations are influenced by Pulo Aceh and the North of the Malacca Strait. The amplitude and phase model results for the four stations show compliance with the TMD data.

3.2. Sea level elevation of tides

Fig. 12, Fig. 13, Fig. 14, Fig. 15 is a time series of tidal elevations for February 2019 at Lhoknga, Ulee Lheue, Lampulo, and Alue Naga stations. Based on the model, the tidal elevation in the four stations reached a maximum of 0.55 m; 0.71 m; 0.72 m; 0.74 m and a minimum of −0.54 m; −0.69; −0.7 m; −0.72 m. Meanwhile, the assimilation of TMD data showed that the tidal elevation reached a maximum of 0.6 m; 0.69 m; 0.72 m; 0.74 m and a minimum of −0.58 m; −0.67; −0.7 m; −0.72 m.

Fig. 12.

Sea level elevation of Lhoknga in February 2019 (m).

Fig. 13.

Sea level elevation of Ulee Lheue in February 2019 (m).

Fig. 14.

Sea level elevation of Lampulo in February 2019 (m).

Fig. 15.

Sea level elevation of Alue Naga in February 2019 (m).

Based on the model, the tidal elevation results for the four stations correspond to the TMD data with correlations of 0.9945, 0.9988, 0.9992, and 0.9992, respectively.

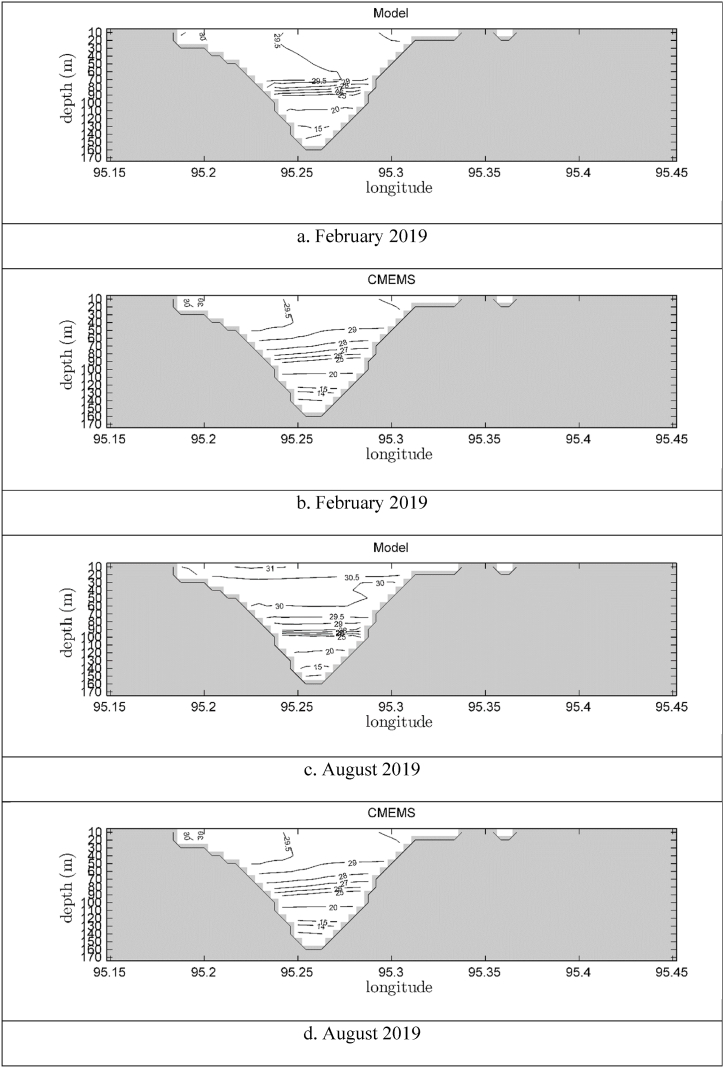

3.3. Sea temperature and sea salinity

Fig. 16, Fig. 17 are sea surface temperature and sea surface salinity for February and August 2019, respectively. Based on the model, sea surface temperatures ranged from 29.4 °C to 30.3 °C in February 2019 (Fig. 16a,b) and ranged from 29.6 °C to 31.2 °C in August 2019 (Fig. 16c,d). The sea surface salinity of the model ranged from 32 ppt to 34.2 ppt in February 2019 (Fig. 17a,b) and ranged from 33.1 ppt to 33.7 ppt in August 2019 (Fig. 17c,d). Fig. 18, Fig. 19 are cross sections of ocean temperature and salinity at 5.60833°N and 92.5°E. At 5.60833°N, temperatures ranged from 13 °C to 30 °C in February 2019 and ranged from 13 °C to 31 °C in August 2019 (Fig. 18a,b,c,d). Meanwhile, at 92.5°E, temperatures ranged from 29 °C to 30 °C in February 2019 and ranged from 29 °C to 31 °C in August 2019 (Fig. 18e,f,g,h). For the cross section of sea salinity at 5.60833°N of the model ranged from 32.5 ppt to 35 ppt in February 2019 and ranged from 32.5 ppt to 35 ppt in August 2019 (Fig. 19a,b,c,d). Whereas at 92.5°E, sea salinity of the model ranged from 33 ppt to 34 ppt in February 2019 and ranged from 33 ppt to 34 ppt in August 2019 (Fig. 19e,f,g,h). The results of the sea temperature and sea salinity models agree with the CMEMS data.

Fig. 16.

Sea surface temperature in February and August 2019 based on model and CMEMS data (°C). (derived from https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/GLOBAL_MULTIYEAR_PHY_001_030/description). a. based on model February 2019. b. based on CMEMS data February 2019. c. same as a, but for August 2019. d. same as b, but for August 2019.

Fig. 17.

Sea surface salinity in February and August 2019 based on model and CMEMS data (ppt). (derived from https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/GLOBAL_MULTIYEAR_PHY_001_030/description). a. based on model February 2019. b. based on CMEMS data February 2019. c. same as a, but for August 2019. d. same as b, but for August 2019.

Fig. 18.

Cross section sea temperature in February and August 2019 based on model and CMEMS data (°C). a. based on model February 2019 in 5.60833° N. b. based on CMEMS data February 2019 in 5.60833° N. c. same as a, but for August 2019. d. same as b, but for August 2019. e. same a, but for 95.2° E. f. same b, but for 95.2° E. g. same as e, but for August 2019. h. same as f, but for August 2019.

Fig. 19.

Cross section sea salinity in February and August 2019 based on model and CMEMS data (ppt). a. based on model February 2019 in 5.60833° N. b. based on CMEMS data February 2019 in 5.60833° N. c. same as a, but for August 2019. d. same as b, but for August 2019. e. same a, but for 95.2° E. f. same b, but for 95.2° E. g. same as e, but for August 2019. h. same as f, but for August 2019.

3.4. Current circulation

To observe the hydrodynamics of the NWA, surface currents and bottom currents during February and August are shown in Fig. 20, Fig. 21, Fig. 22, Fig. 23, respectively. Circulating surface currents are currents up to a depth of 10 m under the sea while undersea currents are currents near the seabed. These high resolution current circulations are verified with global circulation from CMEMS.

Fig. 20.

Surface current vector in February 2019 (m/s). a. based on model with 462.5 m resolution. b. based on CMEMS with 5 km resolution.

Fig. 21.

Surface current vector in August 2019 (m/s). a. based on model with 462.5 m resolution. b. based on CMEMS with 5 km resolution.

Fig. 22.

Bottom current vector in February 2019 (m/s).

Fig. 23.

Bottom current vector in August 2019 (m/s).

For the sea surface current circulation in February 2019 which represented the northeast monsoon, the current velocity reached 0.1 m/s to 0.3 m/s in the west of the NWA towards the west at 5.53° N; 5.54° N; 5.57° N and 0.3 m/s in the north towards the south (Fig. 20). Meanwhile, in August 2019 which represented the southwest monsoon, the circulation of sea surface currents reached 0.1 m/s to 0.2 m/s in the western part of the NWA towards the west at 5.57° N; 5.59° N; 5.60° N and 0.3 m/s in the northern part towards the north (Fig. 21).

Fig. 22, Fig. 23 show the average bottom current circulation in the northeast (February 2019) and southwest (August 2019) monsoons. The circulation of bottom currents in February 2019 in the northern part reached 0.1 m/s towards the West, North, South of the NWA and in the western part, the average current velocity was close to zero, except at 5.57° N; 5.59° N; 5.60° N reached 0.3 m/s. In the northern part, current velocity also reached 0.3 m/s (Fig. 22). Meanwhile, the circulation of bottom currents in August 2019 in the northern part reached 0.15 m/s towards the West, North, South and East of NWA and in the western part, the average current velocity was close to zero, except at 5.60° N reached 0.2 m/s. In the northern part, current velocity also reached 0.2 m/s (Fig. 23).

In February, the surface current circulation from the NWA moves south towards the coast of Aceh (Fig. 20a). This circulation then meets the circulation of incoming flows from the western part of the small strait of Aceh. The convergent current circulation allows for the downwelling process in North Pulo Aceh during February. The underwater circulation around the Aceh coastline also tends to be diverted offshore (Fig. 22). Meanwhile, the inflow from the western part of the small strait of Aceh is still quite strong. Off the coast of Lhok Nga or the western part of Aceh the current is relatively weak and flows to the north.

In August, the surface current circulation in the NWA is diverted back to the North (Fig. 21a). Meanwhile, circulation originating from the western part of the Aceh Strait was relatively weak compared to February. On the other hand, off the coast of Lhok Nga or the western part of Aceh, currents to the north are slightly stronger than in February. Compared to February, in August the undersea current circulation is relatively weak (Fig. 23). Relatively strong northeasterly winds during February resulted in convergent currents in North Aceh. Meanwhile, when the waters of Aceh are dominated by the southwest or west winds in August, the convergent circulation in North Aceh weakens. This current condition was confirmed according to the seasonal surface currents of Aceh waters, namely February and August (1985–2003) from Rizal et al. [9]. Based on Rizal et al. [9], the circulation of surface currents entering from the west coast of Aceh to the north of Aceh strengthened during February. Meanwhile, the current circulation originating from the eastern part of Aceh strengthened in August.

If the surface currents from the model simulation are compared with CMEMS [42,43], as can be seen in Figs. 20b and 21b, the February current is heading northwest, while the August current is heading east and south in the coastal waters of Lhok Nga. Surface currents from CMEMS have lower resolution than the model, so information on currents near the coast is not recorded, instead the model simulation results clearly record nearshore current patterns.

3.5. Total suspended sediment concentration

Fig. 24, Fig. 25 show the distribution pattern of the total suspended sediment concentration in February and August 2019. The distribution pattern of the total suspended sediment concentration in February 2019 ranged from 1.9 mg/l to 4 mg/l. In the western and northern parts of the NWA towards the coast, the total suspended sediment concentration reached 2.8 mg/l and in the eastern part towards the coast, it reached 4 mg/l. The distribution pattern of total suspended sediment concentration from VIIRS data ranged from 2 mg/l to 4.1 mg/l. In the western and northern parts of the NWA towards the coast, the total suspended sediment concentration reached 2.4 mg/l and in the eastern part, it reached 4.1 mg/l (Fig. 24).

Fig. 24.

Surface total suspended sediment concentration in February 2019 based on model and VIIRS data (mg/l). (derived from https://www.star.nesdis.noaa.gov/thredds/dodsC/CoastWatch/VIIRS/SCIENCE/kd490/Weekly2/WW00, see text for explanation). a. based on model February 5, 2019. b. based on VIIRS data February 5, 2019. c. same as a, but for February 12, 2019. d. same as b, but for February 12, 2019. e. same as a, but for February 19, 2019. f. same as b, but for February 19, 2019.

Fig. 25.

Surface total suspended sediment concentration in August 2019 based on model and VIIRS data (mg/l). (derived from https://www.star.nesdis.noaa.gov/thredds/dodsC/CoastWatch/VIIRS/SCIENCE/kd490/Weekly2/WW00, see text for explanation). a. based on model August 6, 2019. b. based on VIIRS data August 6, 2019. c. same as a, but for August 13, 2019. d. same as b, but for August 13, 2019. e. same as a, but for August 20, 2019. f. same as b, but for August 20, 2019.

The distribution pattern of the total suspended sediment concentration in August 2019 ranged from 1.8 mg/l to 3.3 mg/l. In the western and northern parts of the NWA towards the coast, the total suspended sediment concentration reached 2,7 mg/l and in the eastern part, the value reached 3.3 mg/l. Furthermore, the distribution pattern of total suspended sediment concentration from VIIRS data ranged from 2.1 mg/l to 3.4 mg/l. In the western and northern parts of the NWA towards the coast, the total suspended sediment concentration reached 2.3 mg/l and in the eastern part, it was 3.4 mg/l (Fig. 25).

The total suspended sediment concentration value was high near the coast and low away from the coast. Near the coast or rivers, the total suspended sediment increases with the tidal amplitude [44]. TSS concentration in February 2019 (NE monsoon) was higher than August 2019 (SW monsoon) (Fig. 24, Fig. 25). According to Fabrius et al. [45] and Nasrabadi et al. [46], TSS concentration increases in rainy season while decreases in dry season. The dry season of NWA occurs in August while the end of the rainy season occurs in February. In this month, the amount of runs off from the coast and the rivers cause a high TSS in NWA. It is different from August, where TSS is low. TSS is always high around estuary, such as Krueng Raba in Lhoknga, Krueng Aceh in Ulee Lheue, Krueng Aceh in Lampulo, and Krueng Cut in Alue Naga.

Table 3, Table 4 show the surface total suspended sediment concentration for February and August 2019 at Lhoknga, Ulee Lheue, Lampulo, and Alue Naga stations. The values in February 2019 ranged from 2.2 mg/l to 4.1 mg/l (Table 3), while those of August ranged from 2.1 mg/l to 3.4 mg/l (Table 4). These results presented in Fig. 24, Fig. 25a, c, e correlated with the VIIRS data shown in Fig. 24, Fig. 25b, d, f. The suitability of the surface total suspended sediment concentration results from the model and VIIRS data are also shown in Table 3, Table 4

Table 3.

Surface total suspended sediment concentration in February 2019.

| Station | Latitude (°N) | Longitude (°E) | TSS(mg/l) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model |

VIIRS data |

|||||||

| February 5, 2019 | February 12, 2019 | February 19, 2019 | February 5, 2019 | February 12, 2019 | February 19, 2019 | |||

| Lhoknga | 5.4750 | 95.2292 | 2.8013 | 2.1802 | 2.2366 | 2.8346 | 2.1770 | 2.2423 |

| Ulee Lheue | 5.5792 | 95.2833 | 3.1591 | 2.8509 | 2.7139 | 3.2066 | 2.8649 | 2.7308 |

| Lampulo | 5.6083 | 95.3292 | 3.5941 | 3.4211 | 3.1040 | 3.6677 | 3.5094 | 3.1700 |

| Alue Naga | 5.6250 | 95.3542 | 3.6625 | 3.3474 | 3.1419 | 3.7354 | 3.3989 | 3.1890 |

Table 4.

Surface total suspended sediment concentration in August 2019.

| Station | Latitude (°N) | Longitude (°E) | TSS(mg/l) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model |

VIIRS data |

|||||||

| August 6, 2019 | August 13, 2019 | August 20, 2019 | August 6, 2019 | August 13, 2019 | August 20, 2019 | |||

| Lhoknga | 5.4750 | 95.2292 | 2.6814 | 2.0787 | 2.2284 | 2.6935 | 2.0781 | 2.2328 |

| Ulee Lheue | 5.5792 | 95.2833 | 2.7139 | 2.3592 | 2.3203 | 2.7322 | 2.3776 | 2.3346 |

| Lampulo | 5.6083 | 95.3292 | 3.0354 | 2.3827 | 2.2956 | 3.0952 | 2.4170 | 2.3321 |

| Alue Naga | 5.6250 | 95.3542 | 3.0899 | 2.3911 | 2.3325 | 3.1408 | 2.4232 | 2.3601 |

The circulation of ocean currents in February 2019 formed longshore currents around the Alue Naga to Ulee Lheue coastline. Longshore currents move from the north and east to the west of the waters. This circulation disperses sediment from offshore Aceh and Alue Naga towards Ulee Lheue. Thus, although suspended sediments are relatively high (3.3 mg/L) at the Lampulo or Alue Naga stations, an increase in suspended sediments occurs around the Ulee Lheue coastline. However, with the formation of convergent currents on the north coast of Aceh, suspended sediments sink to the bottom of the sea, so suspended sediments in the surface layer decrease.

4. Conclusions

A non-hydrostatic three-dimensional (3D) modeling was performed in this study on NWA. The Amplitude and Phase model results of M2, S2, K1, O1, N2, K2, P1, Q1 showed conformity with the TMD data. Based on the results of surface current circulation, the August 2019 current was stronger than that of February in the western part of NWA, except at 5.57° N; 5.59° N; 5.60° N. The surface currents in the western part of NWA reached 0.1 m/s in February and 0.15 m/s in August 2019. Meanwhile, Surface currents were higher in the northern part of the NWA towards the south in February and north in August. The circulation of bottom currents in August 2019 was also stronger compared to that of February in the western part of NWA, except at 5.57° N; 5.59° N; 5.60° N. The current circulation in February was observed to converge in the NWA due to strong input from the western part of the NWA. This condition was confirmed according to the results of previous studies.

Surface current circulation plays an important role in the distribution of the total suspended sediment concentration. Based on the model results, the concentration value was lower in August 2019 than in February. Furthermore, the results showed conformity with the extraction and assimilation of VIIRS data.

This study provides data that can be used for the control of marine protected areas, port development, industries around the coast, offshore, and fishing activities. In addition, the results are applicable for seawater quality control in dealing with marine pollution.

Author contribution statement

Ichsan Setiawan: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Yudi Haditiar: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Muhammad Syukri; Nazli Ismail; Syamsul Rizal: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Data availability statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology, Indonesia for the financial assistance under the 'Grant for Penelitian Terapan Unggulan Perguruan Tinggi', with a contract number: 549/UN11.2.1/PT.01.03/DPRM/2023 and the 'Grant for Penelitian Dasar Unggulan Perguruan Tinggi', with a contract number: 107/UN11.2.1/PT.01.03/DPRM/2022.

References

- 1.Haridhi H.A., Nanda M., Haditiar Y., Rizal S. Application of Rapid Appraisals of Fisheries Management System (RAFMS) to identify the seasonal variation of fishing ground locations and its corresponding fish species availability at Aceh waters, Indonesia. Ocean Coast Manag. 2018;154:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.12.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du Y., Wang D., Zhang J., Wang Y.P., Fan D. Estimation of initial conditions for surface suspended sediment simulations with the adjoint method: a case study in Hangzhou Bay. Continent. Shelf Res. 2021;227 doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2021.104526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang Y., Guan W., Deleersnijder E., He Z. Hydrodynamic and sediment transport modelling in the Pearl River Estuary and adjacent Chinese coastal zone during Typhoon Mangkhut. Continent. Shelf Res. 2022;233 doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2022.104645. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badru G.S., Odunuga S.S., Omojola A.S., Oladipo E.O. Numerical modelling of sediment transport in southwest coast of Nigeria: implications for sustainable management of coastal erosion in the Bight of Benin. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2022;187 doi: 10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2022.104466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Béjar M., Vericat D., Batalla R.J., Gibbins C.N. Variation in flow and suspended sediment transport in a montane river affected by hydropeaking and instream mining. Geomorphology. 2018;310:69–83. doi: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2018.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulz K., Gerkema T. An inversion of the estuarine circulation by sluice water discharge and its impact on suspended sediment transport. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 2018;200:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2017.09.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Putri M.R., Pohlmann T. Lagrangian model simulation of passive tracer dispersion in the Siak Estuary and Malacca Strait. Asian J. Water Environ. Pollut. 2014;11:67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Putri M.R., Pohlmann T. Hydrodynamic and transport model of the Siak estuary. Asian J. Water Environ. Pollut. 2009;6(1):67–80. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rizal S., Damm P., Wahid M.A., Sündermann J., Ilhamsyah Y., Iskandar T., Muhammad General circulation in the Malacca Strait and andaman sea: a numerical model study. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2012;8:479–488. doi: 10.3844/ajessp.2012.479.488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haditiar Y., Putri M.R., Ismail N., Muchlisin Z.A., Rizal S. Numerical simulation of currents and volume transport in the Malacca Strait and part of south China sea. Eng. J. 2019;23(6):129–143. doi: 10.4186/ej.2019.23.6.129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakib S., Besse G., Yin P., Gang D., Hayes D. Sediment transport simulation and design optimization of a novel marsh shoreline protection technology using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2022;37(1):14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsrc.2021.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Setiawan I., Haditiar Y., Ikhwan M., Nufus Z., Syukri M., Ismail N., Rizal S. Modeling of M2-Tide in the western waters of Aceh, Indonesia. J. Sustain. Sci. Manag. 2020;15(8):122–135. doi: 10.46754/jssm.2020.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sindhu B., Unnikrishnan A.S. Characteristics of tides in the Bay of bengal. Mar. Geodesy. 2013;36(4):377–407. doi: 10.1080/01490419.2013.781088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Othmani A., Béjaoui B., Chevalier C., Elhmaidi D., Devenon J.-L., Aleya L. High-resolution numerical modelling of the barotropic tides in the Gulf of Gabes, eastern Mediterranean Sea (Tunisia) J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2017;129:224–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2017.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haditiar Y., Putri M.R., Ismail N., Muchlisin Z.A., Ikhwan M., Rizal S. Numerical study of tides in the Malacca Strait with a 3-D model. Heliyon. 2020;6(9) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang M., Son S., Harding L.W., Jr. Retrieval of diffuse attenuation coefficient in the Chesapeake Bay and turbid ocean regions for satellite ocean color applications. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. 2009;114(C10) doi: 10.1029/2009JC005286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Son S., Wang M. Water properties in Chesapeake Bay from MODIS-aqua measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012;123:163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2012.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang M., Liu X., Jiang L., Son S. 2017. The VIIRS Ocean Color Product Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aura C.M., Musa S., Osore M.K., Kimani E., Alati V.M., Wambiji N., Charo-Karisa H. Quantification of climate change implications for water-based management: a case study of oyster suitability sites occurrence model along the Kenya coast. J. Mar. Syst. 2017;165:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2016.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen M., Duan H., Cao Z., Xue K., Loiselle S., Yesou H. Determination of the downwelling diffuse attenuation coefficient of lake water with the Sentinel-3A OLCI. Rem. Sens. 2017;9(12) doi: 10.3390/rs9121246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang C., Ye H., Tang S. Seasonal variability of diffuse attenuation coefficient in the Pearl River estuary from long-term remote sensing imagery. Rem. Sens. 2020;12(14) doi: 10.3390/rs12142269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rizal S., Iskandar T., Muhammad, Haditiar Y., Ilhamsyah Y., Setiawan I., Sofyan H. Numerical study of the internal wave behaviour in the vertical ocean slice model. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2019;14(5):2836–2846. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rizal S., Wafdan R., Haditiar Y., Ramli M., Halfiani V. Numerical study of lee waves characteristics in the ocean. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2020;15(2):1056–1078. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikhwan M., Haditiar Y., Wafdan R., Ramli M., Muchlisin Z.A., Rizal S. M2 tidal energy extraction in the Western Waters of Aceh, Indonesia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022;159 doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2022.112220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen W.-B., Liu W.-C., Hsu M.-H., Hwang C.-C. Modeling investigation of suspended sediment transport in a tidal estuary using a three-dimensional model. Appl. Math. Model. 2015;39(9):2570–2586. doi: 10.1016/j.apm.2014.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jarvis A., Reuter H.I., Nelson A., Guevara E. 2008. Hole-filled SRTM for the Globe Version 4, Available from the CGIAR-CSI SRTM 90m Database. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tozer B., Sandwell D.T., Smith W.H.F., Olson C., Beale J.R., Wessel P. Global bathymetry and topography at 15 arc sec: SRTM15+ Earth Space Sci. 2019;6(10):1847–1864. doi: 10.1029/2019EA000658. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egbert G.D., Erofeeva S.Y. Efficient inverse modeling of barotropic ocean tides. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2002;19(2):183–204. doi: 10.1175/1520-0426(2002)019<0183:EIMOBO>2.0.CO. 2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalnay E., Kanamitsu M., Kistler R., Collins W., Deaven D., Gandin L., Iredell M., Saha S., White G., Woolen J., Zhu Y., Chelliah M., Ebisuzaki W., Higgins W., Janowiak J., Mo K.C., Ropelewski C., Wang J., Leetmaa A., Reynolds R., Jenne R., Joseph D. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1996;77(3):437–472. doi: 10.1175/1520-0477(1996)077<0437:TNYRP>2.0.CO. 2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guoguang W., Wang Q., Peng W. Accurate evaluation of vertical tidal displacement determined by GPS kinematic precise point positioning: a case study of Hong Kong. Sensors. 2020;19 doi: 10.3390/s19112559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahmoudof S., Banijamali B., Chegini V. Least squares analysis of noise-free tides using energy conservation and relative concentration of periods criteria. J. Persian Gulf. 2012;3(8):13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shu J.-J. Prediction and analysis of tides and tidal currents. Int. Hydrogr. Rev. 2003;4(2):24–29. https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/ihr/article/view/20618 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li S., Liu L., Cai S., Wang G. Tidal harmonic analysis and prediction with least-squares estimation and inaction method. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 2019;220:196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2019.02.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mendes J., Leitão P., Chambel Leitão J., Bartolomeu S., Rodrigues J., Dias J.M. Improvement of an operational forecasting system for extreme tidal events in Santos Estuary (Brazil) Geosciences. 2019;9(12) doi: 10.3390/geosciences9120511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang D., Cao A., Zhang J., Fan D., Liu Y., Zhang Y. A three-dimensional cohesive sediment transport model with data assimilation: model development, sensitivity analysis and parameter estimation. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 2018;206:87–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2016.08.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Auclair F., Estournel C., Floor J.W., Herrmann M., Nguyen C., Marsaleix P. A non-hydrostatic algorithm for free-surface ocean modelling. Ocean Model. 2011;36(1):49–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ocemod.2010.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Castro-Orgaz O., Hager W.H. Non-Hydrostatic Free Surface Flows. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2017. Vertically integrated non-hydrostatic free surface flow equations; pp. 17–79. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu D., Zhong D., Wang G., Zhu Y. A semi-implicit three-dimensional numerical model for non-hydrostatic pressure free-surface flows on an unstructured, sigma grid. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2013;28(1):77–89. doi: 10.1016/S1001-6279(13)60020-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kämpf Jochen. Springer Publishing Company; Autralia: 2010. Advanced Ocean Modelling: Using Open-Source Software. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rizal S., Sündermann J. On the M2-tide of the Malacca Strait: a numerical investigation. Dtsch. Hydrogr. Z. 1994;46(1):61–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02225741. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kochergin V.P. Three-Dimensional Coastal Ocean Models. American Geophysical Union (AGU); 1987. Three-dimensional prognostic models; pp. 201–208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lellouche J.-M., Le Galloudec O., Drévillon M., Régnier C., Greiner E., Garric G., Ferry N., Desportes C., Testut C.E., Bricaud C., Bourdallé-Badie R. Evaluation of global monitoring and forecasting systems at Mercator Océan. Ocean Sci. 2013;9(1):57–81. doi: 10.5194/os-9-57-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lellouche J.-M., Greiner E., Le Galloudec O., Garric G., Regnier C., Drevillon M., Benkiran M., Testut C.E., Bourdalle-Badie R., Gasparin F., Hernandez O. Recent updates to the Copernicus Marine Service global ocean monitoring and forecasting real-time 1∕12° high-resolution system. Ocean Sci. 2018;14(5):1093–1126. doi: 10.5194/os-14-1093-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christiansen T., Wiberg P.L., Milligan T.G. Flow and sediment transport on a tidal salt marsh surface. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 2000;50(3):315–333. doi: 10.1006/ecss.2000.0548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fabricius K.E., Logan M., Weeks S., Brodie J. The effects of river run-off on water clarity across the central Great Barrier Reef. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014;84(1):191. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.05.012. 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nasrabadi T., Ruegner H., Sirdari Z.Z., Schwientek M., Grathwohl P. Using total suspended solids (TSS) and turbidity as proxies for evaluation of metal transport in river water. Appl. Geochem. 2016;68:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2016.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.