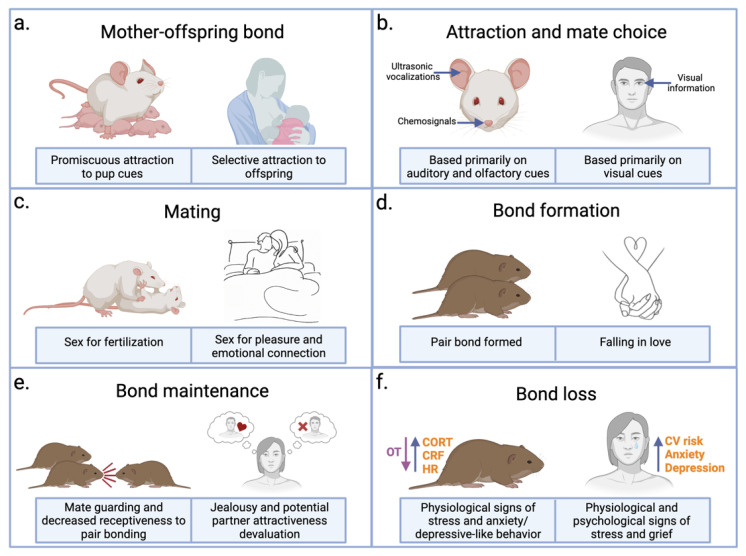

Figure 2.

Comparative processes of bonding. (a) Rodent and human bonding are driven by shared processes across species. Mother–infant bonds are the evolutionary antecedent for pair bonding, relying on selective recognition of infant stimuli and persistent motivational drive to care for offspring. (b) Recognition of and attraction to potential mates in rodents uses primarily auditory and olfactory signals, whereas, in humans, potential partners are initially evaluated primarily based on visual information. (c) For rodents and humans alike, mating facilitates pair bond formation; however, human sexual behavior is complex, with individuals engaging in sexual activity for a variety of reasons, including for pleasure and to strengthen connections. (d) Once a bond has formed, monogamous prairie voles will prefer to mate and spend time with their partner, as well as engage in biparental care. Pair bonding in humans, referred to as “being in love” is accompanied by similar affiliative behaviors. (e) Long-term bonds take work to maintain, especially in the face of other potential mates. Prairie voles engage in mate guarding and have decreased receptiveness to extra-pair bond formations, allowing for bonds to remain stable over time. Humans experience feelings of jealousy and devalue the attractiveness of other individuals, both contributing to long-term bond maintenance. (f) The loss of a partner results in physiological and psychological risk factors across species. Rodents experience a reduction in oxytocin (OT) release accompanied by an increase in corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), as well as elevated heart rate (HR). Loss of a loved one in humans results in elevated cardiovascular (CV) risk, increased experiences of anxiety or depression, and overall feelings of grief. Figure created with BioRender.com (accessed 8 June 2023).