Abstract

Although state-owned enterprises are associated with less efficiency and lead to resource misallocation, they may have stabilizing effect in face of a crisis. Exploiting the COVID-19 pandemic as a natural experiment, we study the role of firm ownership in trade credit provision and find robust evidence that SOEs increase their trade credit to downstream firms more than non-SOEs after the outbreak of the pandemic. Moreover, we explore the underlying mechanism and find that better financing ability and multitask of the SOEs contribute to greater trade credit during the pandemic, and the latter plays a more active role. Further analyses show that SOEs’ advantage in trade credit extension is more pronounced in industries with higher external financial dependence and provinces with a higher level of government involvement, suggesting that SOEs might have greater comparative advantage in screening due to its involvements in local economy during crisis periods. Our paper provides new insights into the real effects of SOEs on the economy.

Keywords: COVID-19, Firm ownership, Trade credit, State-owned enterprises, Chinese economy

1. Introduction

One of the most notable features in Chinese economy is the prevalence of the state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Although the state ownership has declined dramatically during the past two decades, the share of SOEs in industrial sector is still high (Figure A1 and Figure A2 in the online appendix). The coexistence of SOEs and non-SOEs is one of the most prominent features in Chinese economy even after the privatization process since 1990s. How to explain the existence of SOEs lies in the center to understand China’s reform and development strategy. While an important literature examines the efficiency loss of SOEs in production, investment and asset allocation (Song et al., 2011, Huang et al., 2017), the 2008 financial crisis arouse academic and policy attention on the role of SOEs in stabilizing the economy (Reddy et al., 2016; Liu, 2019, Goldman, 2020). However, despite SOEs’ distinctive characteristics as a supplier and their possible macroeconomic consequences, little is known about whether and how SOEs affect the resilience of domestic private-owned enterprises (POEs) to severe economic shocks.

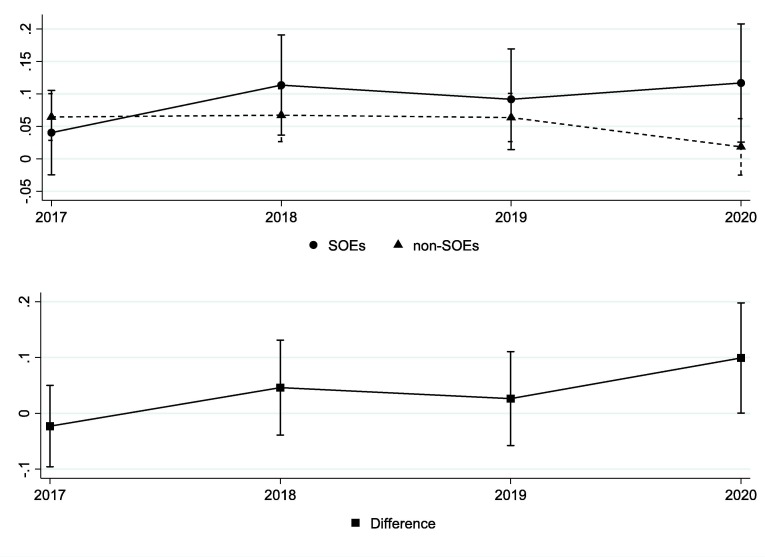

Figure 1.

Response of trade credit provision to subsidy. Note: The figure shows the estimated response of trade credit provision to subsidy for SOEs and non-SOEs, and the differential response between SOEs and non-SOEs with 95% confidence internal.

In this paper, we examine an important mechanism that may affect domestic POEs’ resilience to negative shocks: the trade credit channel. Specifically, our study focuses on the role of trade credit in SOEs’ alleviation of negative liquidity shocks to downstream firms. We are motivated by three stylized facts documented in the prior literature. First, evidence shows that almost two-thirds of international trade is supported by trade credit (Bank for International Settlements, 2014). In the integrated world weaving of payables and receivables, between-firms borrowing creates a flow of trade credit that runs parallel to the flow of goods and service along supply chains. As an important source of financing for downstream firms, trade credit plays a substantial role in firms’ external financing especially in tight domestic credit periods or in financially less developed economies (Fisman and Love, 2003, Love et al., 2007, Lin and Ye, 2018).

Second, it is well documented in the SOEs’ literature that two related important sources of SOEs’ financing advantage come from their better access to domestic financial markets and easy access to government preferential policies (Song et al., 2011, Hsieh and Song, 2015, Harrison et al., 2019), thus SOEs are less financially constrained than private firms in developing countries. Besides, SOEs will put more emphasis on economic stability in the times of crisis as revealed by the multitask theory of SOEs (Bai et al., 2006). These features of SOEs are taken into consideration in the theoretical model on Chinese economy (Chang et al., 2019, Liu et al., 2021).

Third, the difference in the motivation between SOEs and non-SOEs could shape the differential response of trade credit provision during crisis periods. On the one hand, SOEs will pursue non-economic goals according to the multitask theory of SOEs, which leads to some positive externalities (Putniņš, 2015). For example, SOEs provide trade credit to downstream firms during the crisis. This will help downstream firms to avoid going bankrupt and laying off workers, which enables the economy to recover from the crisis more rapidly. Macroeconomic stability could help to reduce systematic risk, uncertainty, and thus facilitate planning within non-SOEs while maintaining high employment could deter the crime, social upheaval and improve social wellbeing, and thus could be considered as a public good. Due to the implicit relationship between SOEs and the government, SOEs will be used to internalize the externality. On the other hand, the trade credit provision involves risk to the creditor, which will discourage firms to provide trade credit when facing with serious shocks. However, SOEs are more likely to tolerate the risk than non-SOEs. The state as an investor is highly diversified and thus generate a portfolio effect which allows SOEs to accept greater amounts of risk (Grøgaard et al., 2019). Moreover, the bailout of the government and the soft budget constraint mitigate the threat of bankruptcy and thus allow SOEs to tolerate greater amounts of risk (Musacchio et al., 2015, Benito et al., 2016, Rygh, 2018). Therefore, SOEs are more willing to extend trade credit relative to non-SOEs especially when risks are potentially high. In summary, SOEs not only have easy access to credit, but also are more motivated to provide trade credit.

Motivated by these stylized facts, we conjecture that financially less constrained SOEs with multitask are capable of extending more trade credit than non-SOEs during crisis periods. To test this hypothesis, we employ a difference-in-differences (DID) strategy in which we compare trade credit supplied by firms with different ownership positions before and after the start of the COVID-19. Using COVID-19 crisis as a natural experiment, we first provide evidence that SOEs extend more trade credit than domestic private firms after the onset of the COVID-19. Furthermore, we find that better financing ability and multitask of SOE are two mechanisms through which SOEs could extend more trade credit during the pandemic, and multitask mechanism is more important to motivate SOEs to provide trade credit.

Our results contribute to the related literature in the following aspects. First, we identify a trade credit channel through which SOEs could provide liquidity during the crisis. To the best of our knowledge, this channel is still unexplored in the literature on the performance and existence of SOEs. The predominant view is that SOEs tend to generate resource misallocations and harm domestic economies (Kruger, 1990). Yet, our findings show that there may be an economic rationale behind the certain aspects of Chinese SOEs, and these SOEs might have mitigated the negative liquidity shocks of POEs and alleviated negative shocks from crisis to the real economy. As existing literature focus on either the efficiency of SOEs, or easy access to credit (Song et al., 2011, Liu, 2019), we move one step forward by exploring the role of trade credit extended of SOEs in stabilizing the economy during times of crisis. Chen et al. (2021) identify the need for such research, but there is currently limited direct evidence. We therefore add to the production networks literature by directly providing the evidence that SOEs extend more trade credits during the crisis. While our study by no means suggests that the existence of SOEs is optimal, our results do show that the financing advantage and multitask of SOEs, especially in the crisis periods, could affect financial conditions of downstream non-SOEs through production network, indicating a stabilizing effect of SOEs on domestic economy. SOEs could play a positive role during the crisis. However, the low efficiency of SOEs could aggravate the resource misallocation and damage the long-run economic performance. In this paper, we only verify that SOEs are willing to provide more trade credit during the crisis.

Second, our findings complement the studies on the role of state shareholders in the corporate governance. Specifically, we provide some new insights on the role of SOEs and the real effect of SOEs on the economy during the crisis. Besides the easier access to external finance, we show that SOEs might have informational advantage in providing trade credit. Information advantage is the principal element for the liquidity provision of financial intermediary, especially bank (Diamond, 1984, Fama, 1985). Local government has information advantage over central government (Qian et al., 2006, Huang et al., 2017) and SOEs have access to government information and data (Capobianco and Christiansen, 2011). The results confirm that local government-owned SOEs extend more credit provisions relative to central government-owned SOEs after controlling the time-varying factors at regional level. Furthermore, the trade credit providing effects of SOEs are more pronounced in industries with more dependence on external finance and in provinces with higher government involvement. The cost of external financing in these industries and areas tends to be higher, indicating that SOEs are more capable in monitoring in terms of extending trade credit probably due to information advantage in production networks.

We also present evidence on the effect of state-owned shares on trade credit provision during the crisis. The monitoring of principal could affect the agency risk (Jia et al., 2019). Following the literature on blockholder, the larger blockholder with further interests at stake will exert more efforts in monitoring the agency (Dharwadkar et al., 2008). Hence, we check the relationship between state-owned shares and trade credit provision and find that a firm with higher state-owned shares is likely to provide more trade credit after the outbreak of COVID-19.

Third, our study complements to the trade credit literature by investigating the heterogeneity in trade credit provision between SOEs, foreign-owned enterprises (FOEs) and domestic POEs and exploring the impact of COVID-19 shock on firms’ trade credit extension. Cull et al. (2009) show that both SOEs and profitable POEs are likely to redistribute the credit during China’s transition. The trade credit is a substitute for bank loans for firms that are shut out of the formal finance. However, they do not explore the role played by SOEs during the crisis. Lin and Ye (2018) document that FOEs provide more trade credit than local POEs in China during tight domestic credit period and that the global liquidity shock due to the 2007-2008 financial crisis attenuates the willingness of FOEs to provide trade credit. Our study departs from theirs in that we identify SOEs as another type of trade credit provider during a crisis period and the magnitude of trade credit extended by SOEs roughly amounts to those extended by FOEs. Moreover, Wang et al. (2019) investigate the inform financing from the demand side of trade credit. Non-SOEs reply more on trade credit financing and when the external financing retrenches during the financial crisis, they will switch financing with trade credit. Ge and Qiu (2007) present similar findings from the demand side of trade credit. Our work also differs because we focus on the supply side of trade credit based on the multitask theory of SOEs.

Finally, we extend our main analysis to the global financial crisis and our paper is related to a large and growing literature concerning the real effects of crisis, especially the COVID-19 crisis, on firms’ behaviors (Ferrando and Ganoulis, 2020, Guerrieri et al., 2020, Jordà et al., 2020). In particular, our work is closely related to the studies by Garcia-Appendini and Montoriol-Garriga, 2013, Carbó-Valverde et al., 2016, Bureau et al., 2021, Chen et al., 2021 and Al-Hadi and Al-Abri (2022). Garcia-Appendini and Montoriol-Garriga (2013) analyze the effect of the 2007-2008 financial crisis on between-firm liquidity provision. Firms with high pre-crisis cash holdings level are likely to provide trade credit to other firms as compared with low pre-crisis cash holdings. Carbó-Valverde et al. (2016) focus on the effect of crisis on small and midsize enterprises (SMEs), and find that credit constrained SMEs rely on trade credit to finance capital expenditure during the period of credit crunch. Bureau et al. (2021) find a trade credit channel which amplify the demand shock faced by firms during the COVID-19 crisis by examining the daily data of payment defaults on suppliers. Al-Hadi and Al-Abri (2022) present cross-country evidence on firms’ trade credit responses to COVID-19-induced monetary policy and fiscal policy and find that there is a difference between trade credit led by monetary intervention and that induced by fiscal intervention. Chen et al. (2021) also provide international evidence on the relationship between SOEs and trade credit. However, the trade credit provision of SOEs will be different in the case of crisis relative to the case of normal period. We add to this literature by identifying another channel through which the firms’ ownership can significantly impact firms’ trade credit provision. The heterogeneity in trade credit extension between SOEs and POEs could at least partially offset the negative shock brought by COVID-19 on the real economy.

The reminder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the data and describes the empirical identification strategy. Section 3 presents the baseline estimation results exploring the consequences of COVID-19 in shaping SOEs’ behavior on trade credit provision. Section 4 tests the robustness of the baseline results and provides more evidences that support the causal explanation of the effect of COVID-19 shock on SOEs’ trade credit extended to their clients. Section 5 explores the mechanisms. Section 6 extends the analysis of information advantage of SOEs during the pandemic and section 7 concludes.

2. Data and Econometric Strategy

2.1. Data

This section discusses the data and empirical strategy used to identify the effect of COVID-19 shock on SOEs’ trade credit provision. Our main variables and firm level characteristics data are obtained from Chinese Stock Market Accounting Research (CSMAR) database. We select A-share listed manufacturing companies in both Shanghai and Shenzhen securities exchanges from the 1st quarter of 2017 to the 4th quarter of 2020. We exclude observations with missing variables used in this study. The whole sample consists of 21581 firm-year-quarter observations. We winsorize the variables at the 1st and 99th percentiles to lessen the influence of outliers.

2.2. Variables

2.2.1. Trade credit provision

To measure our key dependent variable, we follow Levine et al. (2018) and begin with accounts receivable which is a stock entry on balance sheet. We calculate the change in accounts receivable from the beginning of a quarter to the end of this quarter. The positive change suggests that firms provide more goods and services than customers’ pay while the negative change suggests that firms not only receive payments for goods and services that are provided, but also take back between-firm lending from customers.

We calculate the change of accounts receivable to sales ratio (Credit_pro) for each firm. To test our conjecture on the role of SOEs in mitigating the COVID-19 shock, we focus on firms’ willingness to provide trade credit. Besides, we examine the trade credit that firms obtained and calculate the change of accounts payable scaled by cost of goods sold (Credit_rec). We also study net trade credit defined as the change of difference between accounts receivable and payable scaled by sales (Netcredit_pro). Net trade credit reflects the relative willingness to extend trade credit, net of the credit that firms receive themselves.

2.2.2. Firms’ ownership

The key independent variable in our empirical analysis is firms’ ownership. We classify firms based on the nature of equity of the actual controller, the data of which comes from China Listed Firm’s Equity of Nature Research Database, a sub-database of CSMAR. From 2003, the listed firms are required to disclose information on actual controller besides controlling shareholder. Specifically, a firm is classified as a SOE if its actual controller is a SOE, central authority, such as State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council or local authority, such as State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of People’s Government of Beijing Municipality. We construct a dummy variable (Soe) indicating 1 if a firm is a SOE and 0 otherwise.

2.2.3. Other controls

Besides firm’s ownership, there are other firm-specific characteristics that may affect the provision of trade credit, including firms’ age, size, profit margin, liquidity, long-term debt, Tobin’s Q and market concentration which have been emphasized in the literature (Lin and Ye, 2018, Levine et al., 2018). Firm’s age (Age) is the number of years since the establishment and firms’ size (Size) is measured by the total assets adjusted by 2010’s price. We take the logarithm of age and size in the empirical model respectively. The profit margin (Profit) measured by the profit to sales ratio is used to capture firms’ difference in profitability and the liquidity (Liquidity) measured by the share of liquid assets in total assets is used to control for the state of firms’ financial health. Additionally, we include long-term debt to total assets ratio (Debtratio) and the market concentration (Topsale) computed as the total market share of the top five firms at industry-year level to control for the effect of product market structure on trade credit provision. Tobin’s Q (Tobinq) is computed as the share of market value of total assets to book value of total assets.

Table 1 provides summary statistics for these variables from the 1st quarter of 2017 to the 4th quarter of 2020. The average age of firms in the sample is about 19 years and the average of size reaches 80.26 million RMB that is 12.30 million USD in terms of exchange rate at the end of 2020. The share of SOEs in the sample is 27.5% and the share of foreign owned enterprises (FOEs) is 3.12% which is quite lower than that of SOEs. Therefore, we mainly focus on the difference between SOEs and non-SOEs in the following empirical analysis. We also compare these variables of SOEs with that of non-SOEs. Table 1 also shows that SOEs are more mature with larger size, more cash holding and smaller Tobin’s Q.

Table 1.

Summary statistics. This table shows the summary statistics of Chinese manufacturing listed firms from the 1st quarter of 2017 to the 4th quarter of 2020.The last three columns compare the characteristics of SOEs and non-SOEs. Columns 5-6 present the time-series average of corresponding variables for SOEs sample and non-SOEs sample. The last column presents the difference between the time-series average of corresponding variable for SOEs sample and non-SOEs sample. *** significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, * significant at 10%.

| Full Sample | Subsample | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | p50 | Obs | SOE | non-SOEs | Diff. | |

| Credit_pro | 0.0195 | 0.2522 | 0.0132 | 21581 | -0.0153 | 0.0328 | -0.0481 | |

| Credit_rec | 0.0052 | 0.1664 | 0 | 21581 | 0.0019 | 0.0064 | -0.0045 | |

| Netcredit_pro | 0.0250 | 0.2655 | 0.0060 | 21581 | -0.0116 | 0.0389 | -0.0505 | |

| Shortdebt | 0.0772 | 0.5651 | 0.0467 | 21581 | -0.0337 | 0.1193 | -0.1530** | |

| Longdebt | 0.0180 | 0.3170 | 0 | 21581 | 0.0157 | 0.0180 | -0.0023 | |

| Equity_1 | 0.0281 | 0.1653 | 0 | 21581 | 0.0278 | 0.0282 | -0.0004 | |

| Equity_2 | 0.0012 | 0.0347 | 0 | 21581 | 0.0012 | 0.0012 | -3.46e-5 | |

| Cost_1 | 0.7243 | 0.1761 | 0.7532 | 21581 | 0.7784 | 0.7038 | 0.0746*** | |

| Cost_2 | 0.9781 | 0.2710 | 0.9476 | 21581 | 0.9800 | 0.9774 | 0.0026 | |

| Internal_fin | 0.0126 | 0.7057 | 0.0423 | 21581 | 0.0134 | 0.0124 | 0.0010 | |

| Age(year) | 19.4649 | 5.5399 | 19 | 21581 | 21.6245 | 18.6458 | 2.9787*** | |

| Asset(10,000RMB) | 8026.2 | 18069.3 | 3178.3 | 21581 | 14678.0 | 5503.5 | 9174.5*** | |

| Tobinq | 1.8483 | 1.0719 | 1.5310 | 21581 | 1.7194 | 1.8972 | -0.1778*** | |

| Profit | 0.0255 | 2.9126 | 0.0583 | 21581 | 0.0241 | 0.0260 | -0.0019 | |

| Liquidity | 0.5452 | 0.1596 | 0.5450 | 21581 | 0.5549 | 0.5416 | 0.0133 | |

| Debtratio | 0.0727 | 0.0786 | 0.0491 | 21581 | 0.0721 | 0.0730 | -0.0009 | |

| Cash | 0.1388 | 0.0891 | 0.1193 | 21581 | 0.1459 | 0.1361 | 0.0098** | |

| Topsale | 0.2352 | 0.1128 | 0.2279 | 21581 | 0.2466 | 0.2308 | 0.0158** | |

| Soe | 0.2750 | 0.4465 | 0 | 21581 | - | - | - | |

| Fdi | 0.0312 | 0.1738 | 0 | 21581 | - | - | - | |

2.3. Econometric strategy

To analyze the stabilizing effect of SOEs during crisis periods, we exploit the COVID-19 shock which offers a particularly useful setting for this study. In particular, we focus on the difference in trade credit provision behavior between SOEs and non-SOEs as COVID-19 shock unfolds. We employ a method which is similar with Lin and Ye (2018) and Goldman (2020). Specifically, we compare the trade credit provision of firms before and after the outbreak of COVID-19 as a function of government ownership using a difference-in-differences framework. The COVID-19 shock breaks out unexpectedly, and is therefore plausibly exogenous to firms’ behavior.

We are mostly interested in examining the role of firms’ government ownership in mitigating the COVID-19 shock. However, the inferences may be confounded if variation in the ownership as COVDI-19 unfolds is endogenous to unobserved variation in trade credit provision. Our baseline specification, as well as the rest of our analysis described below, is designed to address this issue. Since changes in ownership as the COVID-19 shock unfolds may be related to unobserved changes in trade credit provision, we focus on firms with ownership unchanged during our sample range.

Our baseline specification regresses firm-level quarterly trade credit provision over the 1st quarter of 2017 to the 4th quarter of 2020 on the interaction between firm’s ownership dummy and the pandemic indicator, controlling for relevant firm-specific characteristics, firm fixed effects and time fixed effects. Our specification focuses on the supply side of trade credit. We should control for the demand factors from downstream firms, and thus construct a variable indicating the demand of trade credit following Lin and Ye (2018). To this end, we first obtain each downstream industry’s degree of trade credit dependence from Fisman and Love (2003). The construction of industry’s dependence on trade credit follows Rajan and Zingale (1998) which measure the industry’s dependence on external finance, and use the U.S. data on the ratio of accounts payable to total assets. The industry’s dependence on trade credit reflects the technological aspect of dependence on trade credit innate to each industry. Next, we identify the downstream industry for industry i from China’s input-output table and obtain the intermediate input usage in the downstream industry. We calculate the intermediate input usage share of each downstream industry as a share of intermediate input usage produced by industry i to total production of industry i. Finally, we employ the intermediate input usage share as a weight and compute industry i’s downstream trade credit dependence as the weighted average of its downstream industries’ trade credit dependence which is denoted as Tcreditdep. We then include its interaction term with COVID-19 shock dummy to test whether our results are driven by the supply side or the demand side. In sum, to test our hypothesis, we estimate the following specification.

| (1) |

Where Y indicates the dependent variable, such as the amount of trade credit extended by firm i of year-quarter t scaled by its sales. Soe is an ownership dummy that takes the value of 1 for SOEs and 0 for others. Shock is an indicator variable that takes 1 if the quarter is after the outbreak of COVID-19 that is the 1st quarter of 2020 and afterwards. X is a vector presenting a set of firm-specific control variables. We also include the interaction term of downstream industries’ trade credit dependence (Tcreditdep) with COVID-19 shock dummy to capture the demand of trade credit in the downstream. μi and τt are firm fixed effects and year-quarter fixed effects respectively. The inclusion of firm fixed effects absorbs the level effect of government ownership, and control for all sources of time-invariant variation in trade credit provision across firms and year-quarter time fixed effects capture the unobserved factors potentially affecting trade credit provision that are common to all firms but vary across time, such as fluctuations of economy as well as the changes in macroeconomic policy. εit is an error term. Following Bertrant et al. (2004), standard errors are heteroskedasticity-consistent and clustered at firm level.

We are particularly interested in the coefficient of the interaction term between the SOEs’ dummy and the COVID-19 shock dummy. We expect that SOEs will provide more trade credit after the outbreak of COVID-19. Therefore, a positive coefficient of the interaction term would be consistent with our hypothesis. We also take the net trade credit provision into consideration and examine the differential responses in net trade credit extended between SOEs and non-SOEs to COVID-19 shock. Next, we examine the dynamic effects. On the one hand, if the unobservable factors affecting both ownership and trade credit provision lead to our results, then we could detect this effect before the outbreak of COVID-19. On the other hand, the parallel trend could be checked in this way.

The identification of the main coefficient estimates in equation (1) relies on variation across firms and over time. Furthermore, we identify the coefficients of interest from alternative specifications, for example, by examining the dynamic effects of the pandemic, controlling for potential omitted variables, employing propensity score matching (PSM)-DID approach, using 2008 financial crisis as another exogenous shock and exploring alternative firm ownership measures. We also explore the mechanisms through which firm ownership affects the extension of corporate trade credit.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline results

Table 2 shows the results from estimating equation (1) for trade credit provision based on quarterly firm-level data from the 1st quarter of 2017 to the 4th quarter of 2020. Firm fixed effects and year fixed effects are included in column (1). Firm fixed effects and year-quarter fixed effects are included in the rest specifications to capture any time-invariant characteristics of firms that may drive trade credit policy and any macroeconomic fluctuations that may correlate with trade credit provision decisions. In column (3), we add control variables which are lagged to account for the effect of firm specific characteristics on changes in trade credit extension. In column (4), we further include the interaction of downstream trade credit dependence with COVID-19 shock dummy to control for the downstream demand on trade credit.

Table 2.

Ownership and trade credit provision. This table reports the estimation results from the baseline regression. The dependent variable is Credit_pro in Panel A and is sales (in log) in Panel B. The main independent variable is Soe interacted with shock which is an indicator variable that equals 1 for SOEs after COVID-19 shock, and 0 otherwise. Tcreditdep denotes trade credit dependence of the downstream industry which captures the demand factors of the downstream firms. Other Controls is a vector of firm-level control variables which are lagged, including firm age (in log), total assets (in log), firm Liquidity (liquid assets to total assets ratio), Profitability (operating profit to sales ratio), Debtratio (long term debt to assets ratio), Tobinq and Topsale (market concentration). The main sample covers the periods from the 1st quarter of 2017 to the 4th quarter of 2020. Standard errors (in parentheses) are robust to heteroscedasticity and clustered at firm level. *** significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, * significant at 10%.

| Panel A | Dependent Variable: Credit_pro | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Soe×Shock | 0.1278** | 0.1268*** | 0.1327** | 0.1289** |

| (0.0513) | (0.0478) | (0.0532) | (0.0517) | |

| Tcreditdep× Shock | No | No | No | Yes |

| Other Controls | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | No | No | No |

| Year-quarter FE | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 21581 | 21581 | 18718 | 18718 |

| R2 | 0.0697 | 0.0701 | 0.0787 | 0.0787 |

| Panel B | Dependent Variable: Sales(in log) | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Soe×Shock | 0.0385* | 0.0311 | 0.0609*** | 0.0619*** |

| (0.0209) | (0.0208) | (0.0173) | (0.0174) | |

| Tcreditdep× Shock | No | No | No | Yes |

| Other Controls | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | No | No | No |

| Year-quarter FE | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 21581 | 21581 | 18718 | 18718 |

| R2 | 0.9187 | 0.9297 | 0.9443 | 0.9444 |

In Panel A of Table 2, we find a positive and significant coefficient on the Soe×Shock term, suggesting that SOEs increase their trade credit to downstream firms more than non-SOEs after the outbreak of the pandemic. In column 4, the difference-in-differences coefficient on Soe Shock is 0.1289 and significant at the 5% level, indicating a differential increase in trade credit (scaled by sales) for SOE firms of 12.89 percent, relative to that for non-SOE firms. This size effect is economically large since it represents 16.6% of the sample average of accounts receivable.

There are two potential explanations for the credit provision of SOEs after COVID-19 shock. SOEs could make a large amount of credit sales or allow customer to pay more slowly. We could verify the increased sales on credit directly. We take the logarithm of sales and use the DID specification to investigate whether SOEs increases sales or not when comparing with non-SOEs after COVID-19 shock. Panel B of Table 2 presents the results. From columns (1) through (4), we find a positive and significant coefficient on the Soe×Shock, suggesting that SOEs indeed extends more trade credit to customers through selling more stuff on credit.

3.2. Accounts payable and net trade credit

To further corroborate our conjecture, we examine the differential responses in accounts payable and net trade credit extended between SOEs and non-SOEs to COVID-19 shock. Table 3 presents the results. The dependent variable in columns (1)-(3) is Credit_rec. The estimated coefficient on Soe×Shock is positive and insignificant in all specifications, which suggests that there is no differential response in accounts payable received between SOEs and non-SOEs to COVID-19 shock. There is no evidence that SOEs make less use of trade credit relative to others after the outbreak of COVID-19. This finding is similar to that in Love et al. (2007). They find that the effect of crisis on trade credit usage and provision is different. Financially less vulnerable firms are willing to provide trade credit relative to financially more vulnerable firms. However, there is no significant difference in the usage of trade credit. The dependent variable in columns (4)-(6) is Netcredit_pro. We find a positive and significant estimated coefficient on Soe×Shock in all specifications, which suggests that SOEs provide more trade credit relative to non-SOEs after the outbreak of COVID-19.

Table 3.

Ownership and net trade credit provision. This table reports the results of regressions in which the dependent variable is trade credit acquisition (Credit_rec) in columns (1)-(3) and net trade credit provision (Netcredit_pro) in columns (4)-(6) respectively. The main independent variable is Soe interacted with shock which is an indicator variable that equals 1 for SOEs after COVID-19 shock, and 0 otherwise. Tcreditdep denotes trade credit dependence of the downstream industry which captures the demand factors of the downstream firms. Other Controls is a vector of firm-level control variables which are lagged, including firm age (in log), total assets (in log), firm Liquidity (liquid assets to total assets ratio), Profitability (operating profit to sales ratio), Debtratio (long term debt to assets ratio), Tobinq and Topsale (market concentration). The main sample covers the periods from the 1st quarter of 2017 to the 4th quarter of 2020. Standard errors (in parentheses) are robust to heteroscedasticity and clustered at firm level. *** significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, * significant at 10%.

| Dependent Variable: | Credit_rec | Netcredit_pro | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | ||

| Soe×Shock | 0.0160 | 0.0084 | 0.0079 | 0.1164** | 0.1166** | 0.1131** | |

| (0.0199) | (0.0161) | (0.0162) | (0.0497) | (0.0537) | (0.0522) | ||

| Tcreditdep× Shock | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | |

| Other Controls | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Year-quarter FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Observations | 21581 | 18718 | 18718 | 21581 | 18718 | 18718 | |

| R2 | 0.1521 | 0.1486 | 0.1486 | 0.0714 | 0.0813 | 0.0813 | |

3.3. Dynamic effects

The previous results compare firms’ behavior on trade credit before and after the COVID-19 shock. We next studies the dynamics of differential response of SOEs and non-SOEs to COVID-19 shock. We do this by constructing a series of dummy variables in the standard regression to trace out the quarter-by-quarter effects of firms’ ownership on trade credit extension. We estimate the following specification.

| (2) |

Where the COVID-19 shock dummy variables, Shock-j and Shock+j equal 0 except as follows: Shock-j equals 1 for the jth quarter before the 1th quarter of 2020 while Shock+j equals 1 for the jth quarter after the 1th quarter of 2020. We interact Soe with these dummies respectively and these interaction terms capture the dynamic effects. We consider the first three quarters after the outbreak of COVID-19, the quarter of the outbreak of COVID-19 and the previous three quarters, and exclude the rest quarters in our sample, and thus estimate the dynamic effect of firms’ ownership on the trade credit provision relative to the quarters at the beginning of our sample. μi and τt are firm fixed effects and year-quarter fixed effects respectively.

Table 4 shows the results from estimating equation (1) by adding a series of additional interaction terms, Soe×Shock-j and Soe×Shock+j. The dependence variable in column (1) is Credit_pro, while column (2) reports the results for Netcredit_pro. As shown, the coefficients on the Soe×Shock-j in both specifications are insignificantly different from zero, with no trend in the differential response in trade credit between SOEs and non-SOEs prior to COVID-19 shock. Whereas, the coefficients on Soe×Shock0, Soe×Shock1 and Soe×Shock2 are positive and statistically significant at the 10% level. It is worth noting that trade credit provided by SOEs increases immediately after the outbreak of COVID-19 relative to non-SOEs and such effect fades away after the 3rd quarter of the year 2020. This suggest that SOEs in China react promptly to COVID-19 shock. The check on dynamic effect is in line with the previous findings. In consistence with the parallel trend assumption, the result also suggests that our findings are not driven by pre-event trend heterogeneity in trade credit provision between SOEs and non-SOEs.

Table 4.

Ownership and trade credit provision: Dynamic effects. This table reports the dynamic effects of the pandemic on trade credit provision. The dependent variable is trade credit provision (Credit_pro) in column (1) and net trade credit provision (Netcredit_pro) in column (2) respectively. The main independent variable is the interaction of ownership dummy (Soe) with a series of shock dummies (shock j). We consider the first three quarters after the outbreak of COVID-19, the quarter of the outbreak of COVID-19 and the previous three quarters, and exclude the rest quarters in our sample, and thus estimate the dynamic effect of firms’ ownership on the trade credit provision relative to the quarters at the beginning of our sample. Tcreditdep denotes trade credit dependence of the downstream industry which captures the demand factors of the downstream firms. Other Controls is a vector of firm-level control variables which are lagged, including firm age (in log), total assets (in log), firm Liquidity (liquid assets to total assets ratio), Profitability (operating profit to sales ratio), Debtratio (long term debt to assets ratio), Tobinq and Topsale (market concentration). The main sample covers the periods from the 1st quarter of 2017 to the 4th quarter of 2020. Standard errors (in parentheses) are robust to heteroscedasticity and clustered at firm level. *** significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, * significant at 10%.

| Dependence Variable: | Credit_pro | Netcredit_pro | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | ||

| Soe×Shock3 | 0.0458 | 0.0936 | |

| (0.0494) | (0.0751) | ||

| Soe×Shock2 | 0.1335* | 0.1362* | |

| (0.0699) | (0.0749) | ||

| Soe×Shock1 | 0.1218* | 0.1550** | |

| (0.0692) | (0.0759) | ||

| Soe×Shock0 | 0.1699** | 0.1313* | |

| (0.0713) | (0.0789) | ||

| Soe×Shock-1 | 0.0658 | 0.0552 | |

| (0.1182) | (0.0743) | ||

| Soe×Shock-2 | 0.0809 | 0.1080 | |

| (0.0796) | (0.0849) | ||

| Soe×Shock-3 | 0.1035 | 0.1192 | |

| (0.0712) | (0.0834) | ||

| Tcreditdep× Shock | Yes | Yes | |

| Other Controls | Yes | Yes | |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | |

| Year-quarter FE | Yes | Yes | |

| Observations | 18718 | 18718 | |

| R2 | 0.0701 | 0.0714 |

4. Robustness

4.1. Global financial crisis

We extend our main analysis to the global financial crisis (2008) and present evidence supporting our hypothesis. Garcia-Appendini and Montoriol-Garriga (2013) point out that the rich cash firms provide more trade credit during the financial crisis. However, the role of ownership could also affect firm’s motivation on trade credit provision. Chen et al. (2021) present cross-country evidence that SOEs provide more trade credit relative to non-SOEs, and institutional factors could shape firm’s trade credit behavior.

We repeat the main empirical analysis in the context of global financial crisis. The data covers the period from the 1st quarter of 2005 to the 4th quarter of 2010. We construct a shock dummy (Crisis), which equals 1 after 2007, and 0 otherwise. We rerun the estimation following equation (1). The dependent variable is Credit_pro in columns (1)-(2), and is Netcredit_pro in columns (3)-(4), respectively. Table A1 of the online appendix presents the results. In panel A, we only check the difference in the trade credit provision before and after the global financial crisis for SOEs and non-SOEs separately. Columns (1) and (3) focus on non-SOEs and columns (2) and (4) focus on SOEs. We control for a vector of firm-level characteristics, GDP growth rate, market concentration at industry-level, firm fixed effects and quarter fixed effects. The coefficients on Crisis in columns (2) and (4) are positive and significant. However, the coefficients on Crisis in columns (1) and (3) are insignificant. These findings reveal that SOEs provides more trade credit after the outbreak of global financial crisis while non-SOEs do not response in trade credit provision to the crisis. In Panel B, we are interested in the estimated coefficients of Soe×Shock which are positive and significant, suggesting that SOEs provide more trade credit after the global financial crisis relative to non-SOEs. The evidence of global financial crisis further supports our hypothesis.

4.2. Role of cash holdings

We first examine whether the findings are robust when we take the role of cash holdings into consideration. When liquidity in financial market is scarce, the lower opportunity cost of funds encourages cash-rich firms to extend liquidity through an increase in trade credit (Garcia-Appendini and Montoriol-Garriga, 2013). As shown in Table 1, cash to assets ratio of SOEs is statistically greater than that of non-SOEs at the 5% level, indicating that SOEs could perform better in face of COVID-19 shock. To control for the potential effects of cash holdings, we employ pre-pandemic cash to asset ratio, Cashpre, which denotes the cash to asset ratio one quarter previous to the outbreak of COVID-19.

Table A2 reports the results. The coefficients on Cashpre×Shock are positive but statistically insignificant in columns (1) and (3). The coefficients on Soe×Shock are all significantly positive, suggesting that even controlling for the difference in cash holdings between SOEs and non-SOEs, SOEs still provide more trade credit relative to non-SOEs, and this finding is not driven by the liquidity insurance of cash-rich firms.

We then consider the role of excess cash holdings. Following Opler et al., 1999, Dittmar and Mahrt-Smith, 2007, the excess cash (Excesscash) is defined as the difference between actual and predicted cash (see more detailed calculation of excess cash in Online Appendix B).

We further control for Excesscashpre×Shock in columns (2) and (4) of Table A2. Excesscashpre denotes the Excesscash one quarter previous to the outbreak of COVID-19. Estimation results show that the coefficients on ExcessCashpre×Shock are not significantly different from zero. The coefficients on Soe×Shock are still significantly positive, suggesting that the willingness of SOEs to provide trade credit is not driven by their cash holdings or excess cash holdings.

4.3. Role of foreign-owned enterprises

As discussed in Lin and Ye (2018), foreign-owned enterprises have financing advantage over private-owned enterprises. During a recession, foreign-owned enterprises will use their advantage in international financial market and provide liquidity to other firms through trade credit channel. If this is the case, our results will be underestimated. To further verify our hypothesis, we construct a new dummy variable Fdi which take value of 1 if the actual controller is foreign agent and 0 otherwise. Actually, FOEs are scarce in our sample, and the share of which is only 3.12%. Panel A in Table A3 presents the results. The dependent variable is Credit_pro in columns (1)-(3) and Netcredit_pro in columns (4)-(6), respectively. The coefficients on Fdi×Shock in all specifications are positive and significant, suggesting that FOEs provide more trade credit relative to POEs indeed. This is consistent with the findings of Lin and Ye (2018). Besides, the coefficients on Soe×Shock are still significantly positive. The magnitude of the coefficients on Soe×Shock do not change much when including Fdi×Shock. Panel B in Table A3 presents the results from estimating equation (1) for trade credit provision based on the sample excluding FOEs. Again, the coefficients on Soe×Shock in all specifications are also significantly positive, indicating the robustness of our baseline results

4.4. Excluding lockdown period

To prevent the escalation of COVID-19 shock, China locked down parts of its cities after the outbreak of COVID-19, which strictly curtailed personal mobility as well as economic activities. On 23th January of the year 2020, Wuhan prohibited travel in and out of the city to control the spread of COVID-19 pandemic, and lifted outbound travel restrictions on April 8th. To circumvent the effect of lockdown on supply side of trade credit, we exclude the sample of the 1st quarter in year of 2020 which is the strict lockdown period and examine the robustness of the effect of SOEs on trade credit provision after COVID-19 shock. Estimation results in Table A4 shows that the coefficients on Soe×Shock are positive and statistically significant at the 5% level in all specifications, indicating that SOEs experiencing COVID-19 shock extend more trade credit relative to non-SOEs even excluding the strict lockdown period.

4.5. Analysis based on matched sample

One potential problem relates to the endogeneity of the ownership. We have dropped the firms which have changed the ownership during the analysis period. However, the ownership itself could be correlated with unobservable factors affecting trade credit provision. If the ownership is the result of economic fact leading to changes in trade credit provision, then we should be able to detect the differential response between SOEs and non-SOEs before the COVID19 shock. Pre-trend test in Table 4 indicates that there is no differential response among these two groups of firms before COVID-19 shock.

In the case that the vector of controls is large, it is unlikely to find a similar untreated firm for every treated firm with regard to all characteristics. We therefore adopt a propensity score matching scheme to address this concern. In order to calculate the propensity scores, we use a Logit model to estimate the propensity score for a firm transferred to SOEs based on a broad vector of observable variables including firms’ age, size, liquidity, profit, long-term debt ratio, Tobin’s Q. All control variables are lagged by one period.

After the propensity scores have been estimated, we construct a control group for SOEs by matching algorithms of radius with caliper. The results of balancing test are presented in Table A5, indicating that the matching algorithm successfully meets the key test for balancing. We then check whether the results are robust to the matched sample. Table A6 repents the results. The sample in panel A is constructed using radius with one thousandth caliper and the caliper is set to one ten-thousandth in panel B. The coefficients on Soe×Shock in all specifications are significantly positive, which is in line with our previous findings.

5. Mechanism

SOEs provide more trade credit relative to non-SOEs during the crisis. There are several potential channels through which SOEs changes their behavior on trade credit. The first is the financing advantage possessed by SOEs. The second is the multitask of SOEs which puts more emphasis on economic stability. Besides, information advantage based on financing advantage and better access to government resources might also allow SOEs to extend trade credit during the crisis.

5.1. Better financing ability of SOE

5.1.1. Better access to external finance

To explore the external financing advantage of the SOEs, we examine two main financing sources, debt financing and equity financing. According to political pecking order hypothesis, SOEs are less financial constrained compared with POEs. SOEs function as an intermediary agent which could transfer the financing resource from banks to POEs through trade credit. In this section, we extend our analysis on the differential response between SOEs and non-SOEs to other firm level variables including short-term debt position (Shortdebt) measured by the short-term debt to sales ratio, long-term debt position (Longdebt) measure by the long-term debt to sales ratio, equity issue (Equity_1) measured by a dummy variable which equals 1 if a firm issues shares to its existing shareholders, private placement (Equity_2) measured by a dummy variable which equals 1 if a firm issues shares to a select group of investors. Short-term debt position and long-term debt position capture the debt financing channel while equity issue and private placement capture the equity financing channel.

Panel A in Table 5 presents the results for debt financing channel. The dependent variable in Columns (1)-(3) is short-term debt position. The coefficients of the interaction term Soe×Shock is positive and significant, suggesting that SOEs receive more short-term financing relative to non-SOEs in the front of COVID-19 shock. The dependent variable in columns (4)-(6) is long-term debt position. The coefficients of the interaction term Soe×Shock is insignificantly different from zero. Panel B in Table 5 presents the results for the differential response in equity financing to COVID-19 shock. Columns (1)-(3) investigate whether SOEs obtain more opportunity on right issue after the outbreak of COVID-19 while columns (4)-(6) examine whether SOEs receive more financing from private placement as a response to COVID-19 shock. The coefficients of the interaction term Soe×Shock in all specifications is insignificantly different from zero. These results show that SOEs obtain more short-term financing after the outbreak of COVID-19.

Table 5.

Financial ability of SOEs: External finance mechanism. This table examines the external finance mechanism. In Panel A, the dependent variable is the ratio of short term debt to assets (Shortdebt) in columns (1)-(3) and the ratio of long term debt to assets (Longdebt) in columns (4)-(6), respectively. In Panel B, the dependent variable is equity issue dummy (Equity_1) in columns (1)-(3) and private placement dummy (Equity_2) in columns (4)-(6), respectively. Equity_1 equals 1 if a firm issues shares to its existing shareholders, and Equity_2 equals 1 if a firm issues shares to a select group of investors. The main independent variable is Soe interacted with shock which is an indicator variable that equals 1 for SOEs after COVID-19 shock, and 0 otherwise. Tcreditdep denotes trade credit dependence of the downstream industry which captures the demand factors of the downstream firms. Other Controls is a vector of firm-level control variables which are lagged, including firm age (in log), total assets (in log), firm Liquidity (liquid assets to total assets ratio), Profitability (operating profit to sales ratio), Debtratio (long term debt to assets ratio), Tobinq and Topsale (market concentration). Standard errors (in parentheses) are robust to heteroscedasticity and clustered at firm level. *** significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, * significant at 10%.

| Dependent Variable: | Shortdebt | Longdebt | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Soe×Shock | 0.2676*** | 0.2218** | 0.2251** | 0.0136 | -0.0080 | -0.0081 | |

| (0.0981) | (0.0939) | (0.0959) | (0.0240) | (0.0263) | (0.0266) | ||

| Tcreditdep× Shock | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | |

| Other Controls | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Year-quarter FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Observations | 21581 | 18718 | 18718 | 20784 | 18718 | 18718 | |

| R-squared | 0.0781 | 0.0731 | 0.0731 | 0.1077 | 0.1426 | 0.1426 | |

| Dependent Variable: | Equity_1 | Equity_2 | |||||

| Panel B | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Soe×Shock | -0.0048 | -0.0067 | -0.0068 | 0.0020 | 0.0023 | 0.0023 | |

| (0.0061) | (0.0061) | (0.0061) | (0.0013) | (0.0014) | (0.0015) | ||

| Tcreditdep× Shock | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | |

| Other Controls | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Year-quarter FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Observations | 21581 | 18718 | 18718 | 21581 | 18718 | 18718 | |

| R-squared | 0.1055 | 0.1109 | 0.1110 | 0.0817 | 0.0899 | 0.0900 | |

5.1.2. Internal source of financing

Another aspect of financing advantage of SOEs is that they generate more internal sources of financing. Political connection is an important factor determining the access to government contracts and it has been found to facilitate firms’ access to more financial resources (Shleifer and Vishny, 1994, Faccio et al., 2006). Due to inborn political connection, SOEs obtain preferential treatment in government policies (Harrison et al., 2019). In addition, multitask of SOEs implies that government relies on SOEs to pursue some social objectives (Shleifer, 1998, Bai et al., 2006). Therefore, government could also provide better public services or favorable procurement of production input to connected firms (Ran et al., 2020). SOEs will benefit from cost-saving measures and then generate more internal sources of financing, which in turn, motivates SOEs to provide trade credit through the improvement of liquidity within firms.

To test this hypothesis, we follow Ran et al. (2020) and examine firms’ response of costs to COVID-19 shock. To this end, we construct a measure of costs defined as the ratio between cost of goods sold and total sales (Cost_1). In addition, we consider some other costs correlated with producing and selling goods, such as distribution costs, advertising costs and financing costs. Therefore, we construct another measure of costs defined as the ratio between cost of goods sold plus some indirect costs and total sales (Cost_2).

Panel A of Table 6 presents the results The dependence variable is Cost_1 in columns (1)-(3) and Cost_2 in columns (4)-(6), respectively. We are interested in the coefficient of the interaction term, Soe×Shock which captures the differential response on operating costs of SOEs to the outbreak of COVID-19 relative to non-SOEs. The coefficients of interaction term in columns (1)-(6) are all negative and statistically significant at the 5% level or better. The costs of SOEs response more intensively to COVID-19 shock relative to that of non-SOEs and the difference of costs between SOEs and non-SOEs falls significantly following the onset of COVID-19. These findings suggest that there could be some cost-saving measures specific to SOEs, such as better public services or favorable procurement of production input provided by the government.

Table 6.

Financial ability of SOEs: Internal financing mechanism. This table examines the internal financing ability of SOEs. In Panel A, the dependent variable is the ratio of cost of goods sold to sales (Cost_1) in columns (1) -(3) and the ratio of cost of goods sold plus indirect costs related to good sold to sales (Cost_2) in columns (4)-(6), respectively. In Panel B, the dependent variable is the ratio of the sum of cash stocks, inventories and accounts receivables to sales (Internal_fin) in columns (1)-(3). The main independent variable is Soe interacted with shock which is an indicator variable that equals 1 for SOEs after COVID-19 shock, and 0 otherwise. Tcreditdep denotes trade credit dependence of the downstream industry which captures the demand factors of the downstream firms. Other Controls is a vector of firm-level control variables which are lagged, including firm age (in log), total assets (in log), firm Liquidity (liquid assets to total assets ratio), Profitability (operating profit to sales ratio), Debtratio (long term debt to assets ratio), Tobinq and Topsale (market concentration). Standard errors (in parentheses) are robust to heteroscedasticity and clustered at firm level. *** significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, * significant at 10%.

| Dependent Variable: | Cost_1 | Cost_2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

| Soe×Shock | -0.0098*** | -0.0078** | -0.0078** | -0.0387*** | -0.0344*** | -0.0347** |

| (0.0038) | (0.0038) | (0.0038) | (0.0079) | (0.0083) | (0.0084) | |

| Tcreditdep× Shock | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Other Controls | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year-quarter FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 21581 | 18718 | 18718 | 21581 | 18718 | 18718 |

| R-squared | 0.8115 | 0.8207 | 0.8207 | 0.4361 | 0.4542 | 0.4543 |

| Dependent Variable: | ||||||

| Panel B | (1) | (3) | ||||

| Soe×Shock | 0.1472** | 0.1674*** | ||||

| (0.0630) | (0.0645) | |||||

| Tcreditdep× Shock | No | Yes | ||||

| Other Controls | No | Yes | ||||

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Year-quarter FE | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Observations | 21546 | 18690 | ||||

| R-squared | 0.0836 | 0.0944 | ||||

In addition, we also examine the response of internal source of financing to COVID-19 shock. As discussed, cost-saving measures could improve the internal liquidity of SOEs and thus promote SOEs’ extension of trade credit to their clients relative to non-SOEs. To measure the key variable internal financing (Internal_fin), we follow the existing studies, such as Fazzari and Petersen (1993), and calculate the ratio of changes in a set of proxies (cash stocks, inventories and accounts receivables) to sales for internal financing sources for each firm. Panel B of Table 6 presents the results. The coefficients of interaction term in all columns are all significantly positive, suggesting that SOEs possess better availability of internal finance after COVID-19 shock relative to non-SOEs.

There is still one concern that non-SOEs’ decisions on credit extension may not depend on their financial capacity 1. We address this concern in two aspects. First, we examine the response of SOEs and that of non-SOEs to COVID-19 shock by regressing Credit_pro and Netcredit_pro on shock for SOEs and non-SOEs respectively. Table A7 in the online appendix reports the results. the dependent variable is Credit_pro and Netcredit_pro in columns (1)-(2) and in columns (3)-(4), respectively. The coefficients on Shock for SOE firms are positive and significant. However, the coefficients on Shock for non-SOE firms are insignificant. These findings suggest that SOEs provides more trade credit after the pandemic outbreak while non-SOEs’ trade credit provision does not response much to the shock.

Second, we examine whether domestic non-SOEs with abundant cash will extend more trade credit relative to domestic non-SOEs with less cash by constructing three cash abundant indicators (Cash_d) 2. The first is assigned according to the median of domestic non-SOEs’ cash to assets ratio. Cash_d equals 1 if the cash to assets ratio is above the median, and 0 otherwise. The second and third indicators are assigned according to the 70% quantile and 90% quantile of domestic non-SOEs’ cash to assets ratio respectively. We are interested in the estimated coefficients of the interaction term Cash_d×Shock. Table A9 presents the results. The estimated coefficients of Cash_d×Shock are only significantly positive in columns (3) and (6), suggesting that non-SOEs at top quantile of the cash abundance provide more trade credit. This finding is a little different from Garcia-Appendini and Montoriol-Garriga (2013). Only domestic non-SOEs with cash holdings ranking above 90% quantile show a differential response of trade credit provision to COVID-19 shock relative to other non-SOEs. Given that the average cash to assets ratio of SOEs is 0.15 and the 90% quantile of non-SOEs’ cash abundance is 0.25, this suggests that even if non-SOEs have the same cash abundance with a typical SOE, they will also hesitate to provide trade credit.

We posit that there might be several reasons. First, Chen et al. (2021) document that institutional factors could affect the differential trade credit provision between SOEs and non-SOEs. The less developed financial market and the poor creditor right protection discourage trade credit provision of non-SOEs as trade credit is a kind of loan. The difference of institutional environment between China and the country studied by Garcia-Appendini and Montoriol-Garriga (2013) may shape the differential response of non-SOEs to COVID-19 shock.

Second, financing advantage theory is used to explain our findings from the opportunity side. SOEs could handle more financial resources. However, SOEs with non-economic goals could tolerate more amounts of risk and state with highly diversified investment will generate a portfolio effect (Musacchio et al., 2015, Benito et al., 2016, Rygh, 2018, Grøgaard et al., 2019). Overall, SOEs have advantages in both the opportunity side and the motivation side over non-SOEs.

Third, some studies also document evidences that some financing advantages, such as subsidies are specific to SOEs and also leads to soft budget constraints (Krueger, 1990, Claro, 2006, Eckaus, 2006). Therefore, SOEs are more motivated to provide trade credit during the crisis. We examine the differential response of subsidy between SOEs and non-SOEs during the period of COVID-19 shock following equation (1). After the outbreak of COVID-19, Chinese government reacts rapidly and brings “sizeable and targeted” economic aid to business. Political connection is an important factor determining the flow direction of economic aid and it has been found to facilitate firms’ access to more financial resources (Shleifer and Vishny, 1994, Faccio et al., 2006). Due to inborn political connection, SOEs obtain preferential treatment in government subsidies. In addition, multitask of SOEs implies that government relies on SOEs to pursue some social objectives (Shleifer, 1998, Bai et al., 2006). As a result, government subsidies are primarily provided for SOEs. In summary, compared with non-SOEs, SOEs are favored not only by credit policies, but also by government subsidies (Harrison et al., 2019).

To examine preferential government subsidies, we now compare what happens to government subsidies received by SOEs versus that received by non-SOEs before and after the outbreak of COVID-19. Specifically, government subsidies in our context include subsidies supporting firm’s operation, job stability, loan interest subsidies, tax reduction and COVID-19 subsidies. We examine both the extensive margin and intensive margin effects. First, we construct a dummy (Subsidy) which equal 1 if a firm receives government subsidies and otherwise 0. Second, we calculate government subsidies to sales ratio (Subsidy_r). There are 57.36% firm-year observations of whole sample that receives government subsidies. We address the sample selection issue by estimating an inverse Mill’s ratio which shows the probability that a firm receives government subsidies. We adopt a Probit model first and regress SOEs dummy (Soe) on a set of controls. Next, we calculate the inversed Mill’s ratio bases on the results from the first step regression. Finally, we estimate equation (1) for government subsidies and control for the inversed Mill’s ratio to correct for sample selection bias. Panel A of Table 7 presents the results for the channel of preferential government subsidies. In columns (1)-(4), the dependent variable is Subsidy, a dummy indicating whether a firm receive the government subsidies or not whereas the dependence variable in column (5) is Subsidy_r. In column (5), the inversed Mill’s ratio is controlled to correct the sample selection bias. In columns (1)-(2), we adopt a linear probability model whereas in columns (3)-(4), we adopt a random-effects Probit regression model. The coefficients of interaction term in columns (1)-(4) are all significantly positive and thus reveal an extensive margin effect that SOEs are more likely to receive government subsidies during the crisis. In column (5), the coefficient of interaction term is positive and statistically significant at the 1% level among firms that have received the government subsidies, which suggests an intensive margin effect. The SOEs receive more government subsidies when comparing with non-SOEs during the crisis.

Table 7.

Preferential government subsidies . This table examines advantage of SOEs on obtaining government subsidies. The dependent variable is subsidy dummy (Subsidy) in columns (1)-(4) and subsidy to sales ratio (Subsidy_r) in column (5), respectively. Subsidy dummy (Subsidy) equals 1 if the firm has been granted government subsidies and 0 otherwise. In Panel B, we exclude the COVID-19 subsidies from the government subsidies for a robustness check. The main independent variable is Soe interacted with shock which is an indicator variable that equals 1 for SOEs after COVID-19 shock, and 0 otherwise. Tcreditdep denotes trade credit dependence of the downstream industry which captures the demand factors of the downstream firms. Other Controls is a vector of firm-level control variables which are lagged, including firm age (in log), total assets (in log), firm Liquidity (liquid assets to total assets ratio), Profitability (operating profit to sales ratio), Debtratio (long term debt to assets ratio), Tobinq and Topsale (market concentration). Standard errors (in parentheses) are robust to heteroscedasticity and clustered at firm level. *** significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, * significant at 10%.

| Dependent Variable: | Subsidy | Subsidy_r | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A | OLS | Probit | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |||

| Soe×Shock | 0.0553*** | 0.0712*** | 0.2955*** | 0.3635*** | 0.0869*** | ||

| (0.0167) | (0.0200) | (0.0702) | (0.0856) | (0.0327) | |||

| Other Controls | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | ||

| Inverse Mills Ratio | No | No | No | No | Yes | ||

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | ||

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Observations | 14057 | 8539 | 14320 | 9291 | 4676 | ||

| R-squared | 0.6166 | 0.6347 | 0.5033 | ||||

| Wald Test | 361.06 | 234.39 | |||||

| Dependent Variable: | Subsidy | Subsidy_r | |||||

| Panel B | OLS | Probit | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |||

| Soe×Shock | 0.0478*** | 0.0687*** | 0.2646*** | 0.3549*** | 0.0871*** | ||

| (0.0166) | (0.0198) | (0.0701) | (0.0855) | (0.0348) | |||

| Other Controls | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | ||

| Inverse Mills’ Ratio | No | No | No | No | Yes | ||

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | ||

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Observations | 14057 | 8539 | 14320 | 9291 | 4649 | ||

| R-squared | 0.6188 | 0.6378 | 0.5024 | ||||

| Wald Test | 390.16 | 255.64 | |||||

For robustness check, we exclude the COVID-19 subsidies from the government subsidies as COVID-19 subsidies only appear after the outbreak of COVID-19. Panel B of Table 7 presents the results which are similar with that in Panel A. The coefficients of interaction term, Soe×Shock, in all specifications are significantly positive, suggesting that there are both extensive margin effect and intensive margin effect. This is consistent with our conjecture. SOEs not only have advantages in credit allocation, but also gain preferential government subsidies. In summary, the subsidy presents a similar pattern of the trade credit provision between SOEs and non-SOEs during the period of COVID-19 shock. As financing advantage includes the support of government through the channel of fiscal funding, this finding further supports that SOEs have financing advantage over non-SOEs. SOEs play a similar role as government banks during the crisis. In time of the crisis, banks always hesitate to lend and preserve liquidity because of the increase of uncertainty. However, government banks provide more liquidity during the crisis (Coleman and Feler, 2015, Chen et al., 2016). The government funding specific to government banks leads to the differential lending behavior between government banks and other banks (Ivashina and Scharfstein, 2010, Coleman and Feler, 2015). As presented in Table 7, SOEs have advantage over non-SOEs in terms of the government subsidies that is also one aspect of financial advantage of SOEs (Chen et al., 2021). The state-owned entities including both banks and enterprises will leverage their financial advantage to extend the liquidity during the crisis.

5.2. Multitask of SOEs

The above analysis shows that SOEs provide more trade credit after the COVID-19 shock. However, there is a difference between granting more trade credit due to better access to financing and granting more trade credit due to promoting economic stability. Better access to financial credit is one driving force in motivating the trade credit provision (Garcia-Appendini and Montoriol-Garriga, 2013). However, the multitask theory implies that SOEs may take measures including more trade credit provision during the crisis to maintain economic stability (Chen et al., 2021).

In this section, we conduct several tests to investigate the multitask mechanism. First, we further control for more indicators of financial constraints in the regression to check that given the same financing advantage, whether SOEs provide more trade credit during the crisis. Specifically, we use three indicators of financial constraints including KZ index (Kaplan and Zingales, 1997), SA index (Hadlock and Pierce, 2010) and WW index (Whited and Wu, 2006), the data of which are collected from CSMAR. In Panel A of Table 8 , we find that SOEs provide more trade credit during the crisis relative to non-SOEs after controlling for the indicators of financial constraints (Fincons).

Table 8.

Ownership and trade credit provision: Controlling for financing advantage . This table reports the results of regressions in which the dependent variable is trade credit provision (Credit_pro) in columns (1)-(3) and net trade credit provision (Netcredit_pro) in columns (4)-(6), respectively. The main independent variable is Soe interacted with shock which is an indicator variable that equals 1 for SOEs after COVID-19 shock, and 0 otherwise. Fincons is an indicator for financial constraint and Fincons_b is an indicator for financial constraint in 2019. Columns (1) and (4) refer to KZ index. Columns (2) and (5) refer to SA index while columns (3) and (6) refer to WW index. Tcreditdep denotes trade credit dependence of the downstream industry which captures the demand factors of the downstream firms. Other Controls is a vector of firm-level control variables which are lagged, including firm age (in log), total assets (in log), firm Liquidity (liquid assets to total assets ratio), Profitability (operating profit to sales ratio), Debtratio (long term debt to assets ratio), Tobinq and Topsale (market concentration). Standard errors (in parentheses) are robust to heteroscedasticity and clustered at firm level. *** significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, * significant at 10%.

| Dependent Variable: | Credit_pro | Netcredit_pro | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A | KZ | SA | WW | KZ | SA | WW | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | ||

| Soe×Shock | 0.0972* | 0.1318** | 0.0886*** | 0.1111** | 0.1151** | 0.0723** | |

| (0.0573) | (0.0538) | (0.0301) | (0.0472) | (0.0537) | (0.0302) | ||

| Fincons | -0.0096 | 0.2163 | -0.2604 | -0.0029 | 0.2533 | -0.0300 | |

| (0.0092) | (0.6826) | (0.2836) | (0.0094) | (0.6685) | (0.2415) | ||

| Tcreditdep× Shock | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Other Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Year-quarter FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Observations | 17818 | 18711 | 18125 | 17818 | 18711 | 18125 | |

| R-squared | 0.0777 | 0.0786 | 0.0926 | 0.0777 | 0.0812 | 0.0955 | |

| Dependent Variable: | Credit_pro | Netcredit_pro | |||||

| Panel B | KZ | SA | WW | KZ | SA | WW | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (1) | (2) | (3) | ||

| Soe×Shock | 0.1041** | 0.1330** | 0.1028*** | 0.0905* | 0.1147** | 0.0857** | |

| (0.0526) | (0.0536) | (0.0378) | (0.0532) | (0.0540) | (0.0379) | ||

| Fincons_b×Shock | 0.0090 | -0.0515 | -0.9310 | 0.0178 | -0.0914 | -0.9383 | |

| (0.0287) | (0.0731) | (0.5982) | (0.0283) | (0.0736) | (0.5987) | ||

| Tcreditdep× Shock | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Other Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Year-quarter FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Observations | 17928 | 18718 | 17582 | 17928 | 18718 | 17582 | |

| R-squared | 0.0774 | 0.0787 | 0.0786 | 0.0774 | 0.0813 | 0.0809 | |

Second, we interact the three indicators on financial constraints in 2019 (Fincons_b) with the shock dummy. This could check whether SOEs provide more trade credit after considering the differential responses among firms with different degree of financial constraints to the shock. In panel B of Table 8, we also find that SOEs provide more trade credit during the crisis relative to non-SOEs after considering the differential responses to the crisis.

Third, we extend the analysis to SOEs’ sample. Because SOEs are always financial unconstrained, we expect that multitask mechanism rather than financing advantage mechanism motivates the trade credit provision of SOEs during the crisis if we focus on SOEs’ sample. We construct three cash abundant indicators (Cash_ds). The first is assigned according to the median of SOEs’ cash to assets ratio. Cash_ds equals 1 if the cash to assets ratio is above the median, and 0 otherwise. The second and the third indicators are assigned according to the 70% quantile and 90% quantile of SOEs’ cash to assets ratio respectively. This is similar with the analysis on non-SOEs. The Panel A of Table 9 reports the results. The coefficients of Cash_ds×Shock are all insignificant, suggesting that the financing advantage mechanism alone could not explain the trade credit provision of SOEs.

Table 9.

Ownership and trade credit provision: Considering less cash-abundant SOEs. This table reports the results of regressions in which the dependent variable is trade credit provision (Credit_pro) in columns (1)-(3) and net trade credit provision (Netcredit_pro) in columns (4)-(6), respectively. The sample is restricted to SOEs in Panel A. The main independent variable is Cash_ds interacted with shock which is an indicator variable that equals 1 for cash-abundant SOEs after COVID-19 shock, and 0 otherwise. p50, p70 and p90 indicate the median, 70% quantile, 90% quantile threshold for the assignment of Cash_ds respectively. The sample includes both non-SOEs and less cash-abundant SOEs in Panel B. The main independent variable is Soe interacted with shock which is an indicator variable that equals 1 for SOEs after COVID-19 shock, and 0 otherwise. p50, p30 and p10 indicate the median, 30% quantile, 10% quantile threshold for the classification of less cash-abundant SOEs, respectively. Tcreditdep denotes trade credit dependence of the downstream industry which captures the demand factors of the downstream firms. Other Controls is a vector of firm-level control variables which are lagged, including firm age (in log), total assets (in log), firm Liquidity (liquid assets to total assets ratio), Profitability (operating profit to sales ratio), Debtratio (long term debt to assets ratio), Tobinq and Topsale (market concentration). Standard errors (in parentheses) are robust to heteroscedasticity and clustered at firm level. *** significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, * significant at 10%.

| Dependent Variable: | Credit_pro | Netcredit_pro | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A | p50 | p70 | p90 | p50 | p70 | p90 | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | ||

| Cash_ds×Shock | 0.0438 | 0.0485 | -0.0069 | 0.0176 | 0.0228 | -0.0214 | |

| (0.0332) | (0.0301) | (0.0236) | (0.0249) | (0.0293) | (0.0254) | ||

| Tcreditdep× Shock | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Other Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Year-quarter FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Observations | 5265 | 5265 | 5265 | 5265 | 5265 | 5265 | |

| R-squared | 0.1166 | 0.1166 | 0.1164 | 0.1051 | 0.1051 | 0.1051 | |

| Dependent Variable: | Credit_pro | Netcredit_pro | |||||

| Panel B | p50 | p30 | p10 | p50 | p30 | p10 | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | ||

| Soe×Shock | 0.1135** | 0.1118** | 0.1252*** | 0.1148** | 0.1147** | 0.1435** | |

| (0.0517) | (0.0508) | (0.0474) | (0.0547) | (0.0545) | (0.0609) | ||

| Tcreditdep× Shock | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Other Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Year-quarter FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Observations | 15862 | 15446 | 14405 | 15862 | 15446 | 14405 | |

| R-squared | 0.0787 | 0.0787 | 0.0788 | 0.0813 | 0.0814 | 0.0814 | |

Forth, we construct a sample including both non-SOEs and less cash-abundant SOEs, and perform the regression following equation (1). We construct three less cash-abundant SOEs’ sample. A SOE is classified as a less cash-abundant SOE if the cash to assets ratio is below the median. Columns (1) and (4) in Panel B of Table 9 present the results. Similarly, a SOE is classified as a less cash-abundant SOE if the cash to assets ratio is below the 30% quantile or 10% quantile. Columns (2) and (5) present the results for the sample classified according to the threshold of 30% quantile while columns (3) and (6) present the results for the sample classified according to the threshold of 10% quantile. In the Panel B of Table 9, we find that less cash-abundant SOEs are also more willing to extend trade credit relative to non-SOEs during the crisis. These results prove that many less cash-abundant SOEs show a differential response in trade credit provision compared to their non-SOE counterparts, and furthermore support the multitasks mechanism. The underlying driving force is that SOEs’ objective function concerns social optimality more.