Abstract

The neurohormone melatonin facilitates entrainment of biological rhythms to environmental light-dark conditions as well as phase-shifts of circadian rhythms in constant conditions via activation of the MT1 and/or MT2 receptors expressed within the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus. The efficacy of melatonin and related agonists to modulate biological rhythms can be assessed using two well-validated mouse models of rhythmic behaviors. These models serve as predictive measures of therapeutic efficacy for treatment of circadian phase disorders caused by internal (e.g., clock gene mutations, blindness, depression, seasonal affective disorder) or external (e.g., shift work, travel across time zones) causes in humans. Here we provide background and detailed protocols for quantitative assessment of the magnitude and efficacy of melatonin receptor ligands in mouse circadian phase-shift and re-entrainment paradigms. The utility of these models in the discovery of novel therapeutics acting on melatonin receptors will also be discussed.

Keywords: Melatonin, Melatonin receptors, Phase-shift, Entrainment, Jet lag, Rhythmic behaviors

1. Introduction

1.1. Melatonin and Its Receptors

The ancient molecule melatonin (5-methoxy-N-acetyltryptamine) is produced by almost all living organisms [1] and plays a pivotal role in the regulation of daily physiological processes [2–8]. In mammals, the synthesis of melatonin by the pineal gland follows a circadian rhythm, with a peak in the middle of the night and a trough during the day [9]. The rhythmic secretion of melatonin by pinealocytes is controlled by the timekeeping system within the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), or master biological clock, which is regulated by photic information received by the retina and transduced via the retino-hypothalamic tract to the SCN [10]. In addition to the pineal gland, endogenous melatonin production has also been described in the skin [11], gut [12], and retina [13], supporting its widespread influence on various physiological processes in mammals. Since melatonin peaks in the middle of the night in both diurnal and nocturnal species, independent of sleep or activity phase associations [14], it is known as the “hormone of darkness”, signaling darkness to coordinate physiological processes based on the time of day [2, 15].

Most of the known physiological and pharmacological actions of melatonin are mediated by two high-affinity G protein-coupled receptors termed the MT1 and the MT2 receptors [2, 15–17]. MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors are localized within various brain regions [18–20], peripheral tissues such as the pancreas [21], and the retina [22–24], with highest expression seen in the SCN [25, 26]. Both receptors canonically couple to Gi/o G proteins but have also been shown to couple to other cellular signaling pathways [27, 28]. Inhibition of neuronal firing and phase-shift of the peak of circadian neuronal firing within the SCN are mediated by MT1 and MT2 receptors, respectively, with both receptors involved in the regulation of retinal light sensitivity seemingly via the formation of heterodimers [29]. Although melatonin displays similar affinities at both melatonin receptors [17, 18, 25], the MT2 receptor desensitizes in response to physiological concentrations of melatonin unlike the MT1 receptor [30]. The recent discovery of the MT1 and MT2 crystal structures [31, 32] in addition to studies demonstrating that MT1 receptors are constitutively active in vitro [33, 34] has led to the discovery of selective MT1 melatonin receptor inverse agonists by use of circadian behavioral mouse models [35].

1.2. Modulation of Rhythmic Behaviors by Melatonin Receptor Agonists

Studies investigating the effects of melatonin on biological rhythms in rodents started with the pioneer discovery by Redman et al. [36] where it was demonstrated that melatonin could entrain and synchronize circadian activity in rodents to the light-dark (LD) cycle [36–38]. After further observations, it was later determined that entrainment by melatonin could be maximized by considering time of treatment with respect to time of day and the shift of the LD cycle [39]. Evidence then began to emerge supporting melatonin and related receptor agonists could directly influence phase and entrainment rate of circadian rhythms in rodents [2, 40–47]. Based on these lines of evidence, melatonin was recommended for use in the treatment of jet lag, shift work, as well as circadian rhythm disorders resulting from blindness [48–50]. Today, melatonin and related receptor agonists, such as Circadin (extended-release melatonin), ramelteon (Rozerem), and tasimelteon (Hetlioz), are used in several countries as therapeutics for sleep and/or circadian disorders in humans [51]. Additionally, the nonselective melatonin receptor agonist and serotonin 2C (5-HT2C) receptor antagonist, agomelatine (Valdoxan, Melitor, Thymanax), is used to treat depression in Europe [51]. These therapeutics were discovered in preclinical studies assessing the effect of melatonin receptor ligands on biological rhythms in rodents. This review will discuss two primary in vivo paradigms of rhythmic behaviors to assess the efficacy of melatonin receptor ligands to phase-shift and re-entrain rhythmic behaviors in mouse models and to predict potential therapeutic outcomes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mouse models to study melatonin receptor ligand efficacy on rhythmic behaviors. Schematic defining experimental paradigms utilized to assess the efficacy of melatonin receptor ligands on rhythmic behaviors using circadian mouse models (i.e., phase-shift in constant dark and re-entrainment jet lag paradigm in a LD cycle). The effects of melatonin receptor ligands acting at SCN melatonin receptors to modulate rhythmic behaviors can be measured by monitoring running wheel activity in either mouse model. Running wheels are equipped with magnets that allow for the registration of each wheel revolution as the magnet passes a microswitch attached to the cage lid as depicted. SCN melatonin receptors that were labelled using 2-[125I]-iodomelatonin in coronal brain slices from C3H/HeN mice are depicted in the representative autoradiogram

1.3. Phase-shift of Circadian Activity Rhythms by Melatonin Receptor Ligands

The current protocols used for testing the effects of melatonin receptor compounds on circadian phase in mice [46, 47, 52, 53] were originally based on the human phase response curve [41, 54–56]. Importantly, the amplitude and direction of the phase response curve (PRC) to melatonin in both humans and C3H/HeN mice are identical [46, 54, 56] (Fig. 2) despite phase/activity differences (nocturnal vs. diurnal). This supports the translational power of using the phase-shift paradigm to study rhythmic behaviors and pharmacological effects of melatonin receptor ligands in mice.

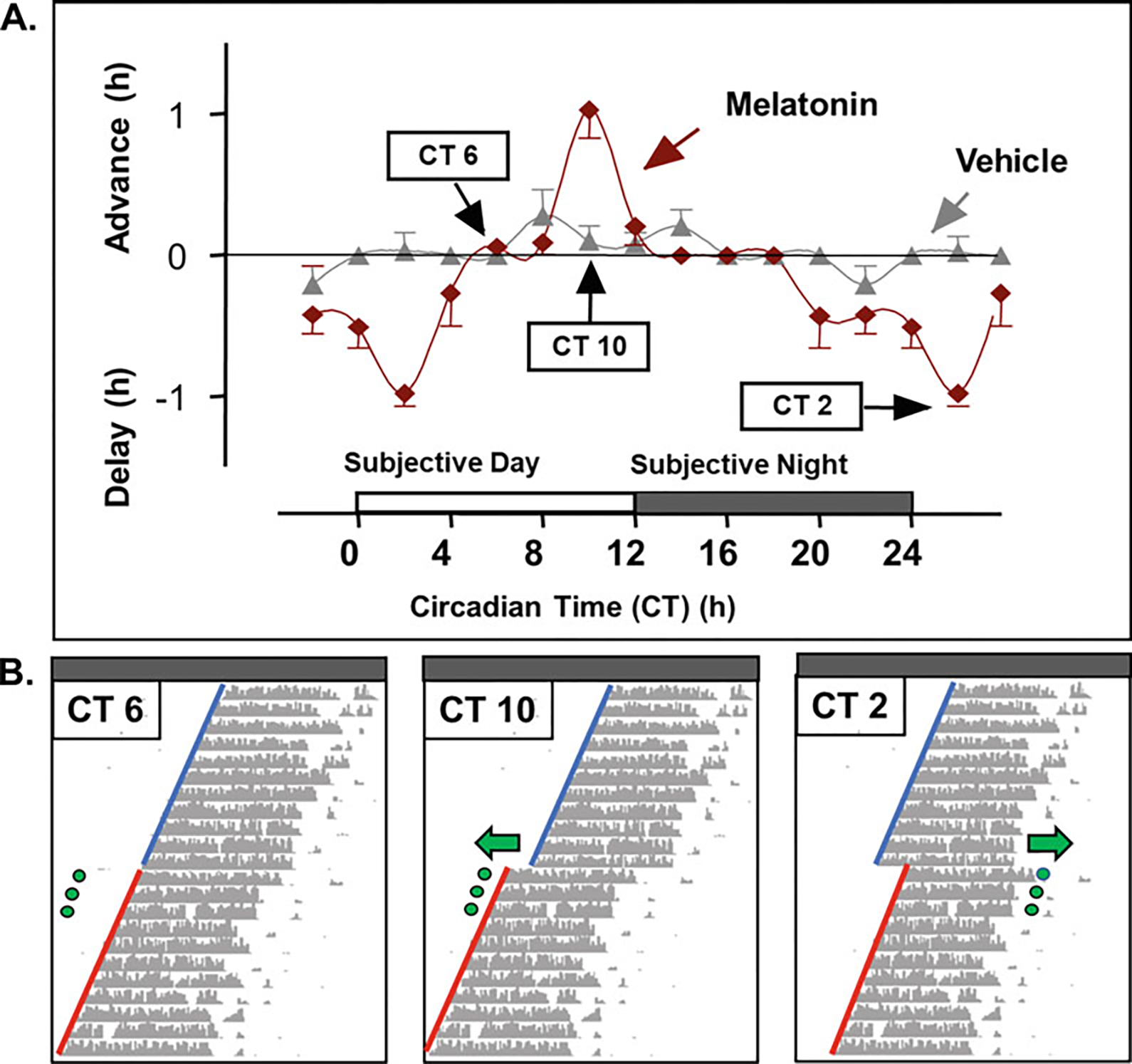

Fig. 2.

Phase response curve to melatonin. Phase-shift of the onset of running wheel activity by melatonin across the circadian cycle. (a) Phase response curve to three consecutive melatonin treatments (90ug/mouse, s.c.) at corresponding circadian (CT) times in C3H/HeN mice housed in constant darkness. (b) Representative actograms for mice treated with melatonin at CT 6 (left), CT 10 (middle), and CT 2 (right). Green dots represent injections with arrows showing the direction of the phase-shift in running wheel activity onset. Blue lines represent pretreatment running wheel activity onsets, while red lines represent posttreatment onsets which are used to calculate phase-shift values (delay or advance). (Figures a and b are modified from [46] with permission)

In the circadian phase-shift paradigm (Fig. 3), mice are subjected to constant conditions, such as constant darkness, to allow for measuring the endogenous free-running period of circadian activity rhythms [35, 57–59]. Once stable free-running activity rhythms are established, treatment is then administered for three consecutive days, and the activity onsets are then measured over a period of several weeks. The difference in the phase of locomotor activity onsets pre- and posttreatment determines the magnitude (shift) and direction (advance or delay) of the phase-shift.

Fig. 3.

Phase-shift paradigm. Illustrations of the phase-shift paradigm when melatonin is administered at CT 10 (a) or CT 2 (b). Mice are housed in a 12/12 light-dark cycle for 10–14 days prior to being released into constant darkness. Once stable rhythms of running wheel activity onsets develop in constant darkness (10–14 days), mice are treated with melatonin at the appropriate CT time for 3 days and allowed 10–14 days of undisturbed running wheel activity to assess treatment effects on circadian phase of onset of activity. Pretreatment phase of onsets is shown by the dotted red line, while posttreatment phase of onsets is indicated with the dotted green line. ZT = zeitgeber time (ZT 0 = lights on in a 12/12 LD cycle) CT = circadian time (CT 12 = onset of running wheel activity in constant dark)

Beyond the translational power of the phase-shift paradigm, this model has been importantly validated in mice for studying melatonin receptor pharmacology where the effects of melatonin were shown to be time of day, dose, and receptor dependent [46, 52, 53]. Additionally, the phase-shift paradigm has also been successfully used to determine the phase-shifting effects of the nonselective melatonin receptor agonist, ramelteon, showing a PRC indistinguishable from melatonin [59] and is consistent with its clinical effects in humans [60]. Furthermore, the paradigm has also been recently used to successfully study the effects of a carbamate insecticide and novel MT1 selective inverse agonists on circadian phase [35, 58]. Lastly, the effects of melatonin receptor ligands in the phase-shift paradigm likely reflect direct interactions between these compounds and melatonin receptors expressed within the SCN, as rats with SCN lesions do not alter their circadian rhythms of activity in response to melatonin [61]. Taken together, these observations support the circadian phase-shift model is a useful method for characterizing the effects of melatonin receptor ligands.

1.4. Modulation of Re-entrainment by Melatonin Receptor Ligands

In addition to the phase-shift model, the jet lag re-entrainment paradigm (Fig. 4) is a useful in vivo model for assessing melatonin receptor ligand efficacy in rodents and used to predict clinical effects in humans. In this paradigm, mice are stably entrained to a standard LD cycle, such as 12 h of light and 12 h of dark, prior to an abrupt advance or delay of the dark onset. Advancing the light-dark cycle models eastward travel, while delaying the light-dark cycle models westward travel across time zones. Once the light-dark cycle has been abruptly shifted to simulate conditions leading to jet lag, the number of days required for animals to realign or re-entrain their activity rhythms to the new environmental light-dark conditions is measured [35, 53, 57, 62]. These shifts in the LD cycle can also be accompanied with drug treatments to measure changes in the rate of re-entrainment in response to circadian modulators, such as melatonin receptor ligands.

Fig. 4.

Re-entrainment jet lag paradigm. Illustration of the re-entrainment jet lag models for eastbound (a) and westbound travel (b). Both models simulate a 6-h shift in light-dark cycle akin to traveling from New York City, USA, to Paris, France (eastbound model), or Paris, France, to New York City, USA (westbound model). In both models, mice are housed in a 12/12 light-dark cycle for 2 weeks prior to treatment with melatonin or another melatonin receptor ligand. Once stable entrainment of running wheel activity to the dark onset is achieved, treatment occurs for 3 days (arrows with black dots) just prior to the new dark onset in the eastbound model and prior to the old dark onset in the westbound model. Mice are then allowed 2 weeks of undisturbed running wheel activity. Treatment can also be administered at other times, for example, at the new dark onset [79] in the westbound model (white dots, b). ZT = zeitgeber time (ZT 0 = lights on in a 12/12 LD cycle)

Exogenous melatonin facilitates re-entrainment of wheel running activity rhythms following an advance of the dark onset in the jet lag paradigm via actions at the MT1 receptor [35, 53]. Similarly, the nonselective MT1/MT2 agonist agomelatine has also been shown to accelerate re-entrainment rate in this paradigm. Dubocovich et al. [53] and Pfeffer et al. [62] both studied the effects of melatonin on the re-entrainment rate of wheel running activity rhythms in the eastbound jet lag paradigm. Interestingly, results from these studies implicate the MT1 receptor when exogenous and the MT2 receptor when endogenous melatonin levels are at play, highlighting the contributions of both receptors in different contexts. In the westbound jet lag model, where the light-dark cycle is delayed, endogenous melatonin has little to no effect on the re-entrainment of wheel running activity rhythms [62, 63], perhaps due to the potent phase-delaying effect of light during the early subjective night [46, 54, 64]. Furthermore, while melatonin facilitates re-entrainment of wheel running activity by reducing the number of days to re-entrainment (accelerates) [53], luzindole, a mixed MT1/MT2 antagonist/inverse agonist, and two novel MT1 inverse agonists act opposite to that of melatonin (decelerate), increasing the number of days to re-entrainment in the jet lag paradigm [35] (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Efficacy of melatonin receptor ligands in the jet lag paradigm. Depiction of pharmacological efficacy as determined in the eastbound re-entrainment jet lag model. Agonists like melatonin (green; 4–6 days) accelerate the rate of re-entrainment of running wheel activity to the new dark onset compared to vehicle (white; 7–9 days). Conversely, inverse agonists (red; 10–14 days) decelerate the basal rate of re-entrainment seen with vehicle (white), an effect opposite of agonists

2. Materials

This section will describe the facilities and necessary equipment for recording locomotor activity rhythms in mice to assess the effect of melatonin and related ligands on rhythmic behaviors controlled by the biological clock in the SCN. The basic facilities and equipment needed to collect wheel running activity data include a dedicated set of rooms with individual control of the LD cycle, light-tight cabinets, cages equipped with running wheels, a computer with data acquisition software, and proper devices to measure humidity, temperature, and light levels.

2.1. Facilities

Facilities include rooms of approximately 10 × 16 ft in size to accommodate three cabinets, each containing three boxes (coffin) stacked one on top of the other and arranged along the perimeter of the room.

All procedures are conducted in light-tight rooms with windows and doors permanently sealed. When possible, it is good practice to build a locked anteroom or a darkroom-revolting door to further minimize light leaks. However, a dark room revolting door represents a barrier to transferring supplies and equipment into the holding room [65].

2.2. Equipment

Running wheels: Mice are single housed in cages (18 × 30 × 12 cm) equipped with a running wheel (Phenome Technologies, Inc., IL, USA) and connected via a magnetic microswitch (see Fig. 1) to a computer that records wheel revolutions using a data collection software [65]. Wheel revolutions are registered using magnets purchased separately and fixed to running wheels. Routine checks of running wheels and wired microswitches are necessary for detecting any magnets that may have detached during the washing process and wires that may have acquired damage.

Cabinets: Cages with running wheels are housed in light-tight, sound-attenuated and well-ventilated cabinets which maintain stable temperature and humidity. Depending on the model and manufacturer, each isolation coffin will hold between 8 and 24 cages. Each of our coffins includes a shelf, creating two levels for cage placement. These levels are equipped with microswitch outlets, enough to support 8–20 cages, therefore limiting the capacity to 24–60 cages per cabinet. Ideally, to avoid confounding effects due to running wheel sounds and/or odors, each mouse should be housed within its own single suite (physical division between each cage-allocated placing). The door of each cabinet is labeled as appropriate with tags indicating the light-dark cycle at each time inside each cabinet compartment.

Ventilation: A consistent air flow is necessary to keep the boxes free of odors, with temperatures kept the same as in the room to maintain the mice in good health. Each coffin contains hooded fans to prevent light from leaking in. The air removed from within the cabinets is directed via a ceiling duct to the room exhaust system to avoid recirculation of this air to other cabinets held within the same room. This is particularly important when females are housed in other isolation boxes within the same room, where pheromones associated with the female estrous cycle may affect the circadian locomotor activity of males [66]. Therefore, it is advisable that male and female mice be housed in separate cabinets to avoid any interference from housing both sexes together.

Lighting: Lighting in each coffin is delivered via LED light panels mounted on the ceiling of each shelf. Our boxes are equipped with green LEDs (Actimetrics, Evanston, IL) arranged to deliver uniform illumination. Green LEDs emit light in the optimal spectrum (476 nm) to entrain mice to a light-dark cycle [67, 68].

2.3. Data Acquisition

Running wheel revolutions are monitored continuously using ClockLab software (Actimetrics, Evanston, IL) or other commercially available platforms. In our system, ClockLab records each time the magnet fixed to the running wheels passes by the microswitch, which registers each wheel revolution (Fig. 1). The lighting regime within each coffin is programmed in ClockLab, allowing for individual manipulation of light settings. Data is collected from up to 256 microswitch channels, including channels allocated as light sensors. The data collection computer is kept on a battery backup in the event of power failure.

Data is collected daily or could also be backed up automatically if computers are connected to a network. The computer time is not adjusted for daylight savings time, preventing light schedule conflicts in the data collection software. During daylight savings time, the lab simply adjusts schedules to account for the 1-h time difference, which must be considered when calculating predicted treatment times. It is important to note that, if the computer is connected to a network, system settings must be adjusted to prohibit the automatic adjustment for daylight saving time.

2.4. Measurement of Environmental Conditions

The handling of mice during the dark (e.g., constant darkness or during the dark phase of the 24-h light/dark cycle) is conducted using red dim safelight (15 watts, Kodak 1A filter) with illuminance of less than 1 lux at the level of the mouse [46, 69] or preferably with night vision goggles. The circadian system is relatively insensitive to red wavelengths [67]; however, the specific red light used should be tested as described by Siepka, Takahashi [65], to ensure it does not alter running wheel activity (e.g., masking) or induce a phase-shift.

Temperature and humidity inside isolation boxes should be recorded continuously using data loggers (HOBO, Onset Computer Corporation, MA, USA) and downloaded as well as checked periodically.

2.5. Circadian and Zeitgeber Time

Zeitgeber Time (ZT). ZT 0 is defined as lights on in nocturnal or diurnal species kept under a LD cycle (e.g., 14/10 LD cycle).

Circadian Time (CT). CT 12 is defined as the onset of activity (phase marker) in nocturnal species, kept in constant conditions (e.g., constant dark).

2.6. Animal Information

Mouse strain: Two mouse stains have been used over the years to study the effect of intact melatonin signaling and exogenous application of melatonin receptor ligands on the circadian phase and re-entrainment of locomotor activity rhythms. Melatonin-deficient (C57BL/6 J) and melatonin-proficient strains of mice (C3H/HeN) are commonly used, with either possessing a targeted deletion of one or both melatonin receptors [62, 63]. Selection of mouse strain will depend on the design of the study. Since only few strains of mice are known to produce melatonin in the pineal gland (e.g., C3H/HeN; CBA) [70], it is important to select mice with intact melatonin signaling when the aim is to understand the physiological effect of endogenous melatonin [6].

Husbandry: Singled-housed mice are provided food and water ad libitum, minimizing the effect of food availability on the circadian phase [71–74]. Cages and water bottles are changed every week, during times that are the least likely to disrupt circadian phase (i.e., during the activity period) and/or the effects of drug treatments. The level of water in the bottles and amount of food pellets in cage tops are monitored daily. In our protocols approved by the University at Buffalo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), cages are changed 4 days before and 10 days after treatment to allow for stabilization of rhythmic running wheel activity after treatment. During this period, the conditions of the bedding are monitored for feces and ammonia buildup; part of the bedding is replaced if necessary. Ammonia-level tests revealed the level of ammonia remained remarkably low for up to 3 weeks in cages housing a single mouse and containing an appropriate amount of bedding.

2.7. Drug Preparation

Drug Preparation:

All compounds to be administered are prepared from a concentrated stock solution. Depending on the solubility of the compound, doses can be diluted from stock solutions prepared in 100% ethanol. Vehicle solutions contain sterile saline and up to no more 30% ethanol. Doses of melatonin receptor ligands can be administered subcutaneously or intraperitoneally at a standard volume of 0.1 mL/30 g or 0.01 mL/g mouse body weightusing the appropriate stock solution concentrations for desired doses. All dilutions should be made directly prior to use for each set of injections. The amount of ethanol in each dose depends on the solubility of the drug in ethanol or other diluent and should always be minimized.

3. Methods

3.1. Phase-Shift of Circadian Activity Rhythms Protocol

The phase dependence of a stimuli-induced phase-shift can be determined by deriving a phase response curve, which describes the relationship between an external stimulus and the subsequent change in the phase of the period of oscillation [46]. This protocol will therefore describe methods for determining the effect of melatonin or related drugs on the phase of the mouse circadian clock in experiments performed under constant conditions (i.e., dark/dark or constant darkness), where the free-running period and the magnitude of a stimulus-induced phase-shift at specific circadian times (CT) can be calculated using the onset of activity which is defined as CT 12. We will also describe procedures to generate a phase response curve to melatonin [46] and the modulation of light-mediated phase-shifts by melatonin receptor ligands.

The protocol for testing the effects of melatonin receptor ligands on the phase of circadian wheel running activity in mice was first described by Benloucif and Dubocovich [46], and subsequently by others [35, 47, 53, 58, 59, 75, 76]. This protocol represents a measurable way of assessing the interaction of melatonin receptor activation in the SCN and the ability of drugs to induce phase-shifts of overt circadian wheel running activity rhythms.

Mice are group housed and maintained in a 12/12 LD cycle for a period of 2 weeks with illuminance at the level of the cage floor maintained at 250–300 lux, before the start of an experiment. Mice are then transferred to cages equipped with running wheels (Fig. 1), immediately after lights off corresponding to the original 12/12 LD cycle to prevent circadian phase-shifts associated with the presentation of novel running wheels [77].

For assessing drug-induced phase-shifts in constant conditions (i.e., DD), mice placed on running wheels are individually housed in a 12/12 LD cycle for 2 weeks or until a stable phase onset is achieved. During this period, mice develop rhythmic wheel running activity patterns with high activity during the dark period and low activity during the light period.

Once a stable rhythm of wheel running activity is established, mice are then transferred to constant dark (DD) starting at the LD transition and given 2 weeks to allow expression of their endogenous free-running period. In DD, mice typically express circadian periods shorter than 24 h, where wheel running activity commences earlier each day in the absence of the light zeitgeber, which provides sensory input to entrain the SCN to a LD cycle.

-

Calculation of treatment time: After establishment of stable free-running circadian wheel running activity rhythms, predetermined treatment clock times for specific circadian times (CT) can be calculated for each mouse. To calculate the clock time corresponding to the selected CT of treatment for each individual mouse on any given experimental day, it is necessary to first determine CT 12 (decimal time adjusted for daylight saving time if necessary) and the period of the circadian rhythm (tau) on the day prior to treatment [46]. The formula to calculate circadian time is as follows:

CT 12 represents circadian time 12 or onset of running wheel activity, and CTT represents the desired circadian time of treatment. CT times can then be converted to clock time by multiplying the decimal value following the ones place by 60 to derive minutes and keeping the ones place value as hours. Or one can simply divide the CT time by 24 in excel, within a cell set to time format. See Table 1 for an example on how to calculate CT and clock time for 3 days of treatment for a single mouse. Note that clock time for a single CT is typically determined for each mouse under the protocols described herein.

Using the predicted CT 12 onsets for each day of treatment for each mouse, a schedule should be prepared for several days of injections around the clock and at the appropriate times for each animal. Injections are carried out under dim red light conditions as previously described. Mice are immediately returned to their home cages after injections and given 2 weeks to assess any effects of treatment on the phase of wheel running activity onsets.

When tau and CT 12 are determined for the day prior to treatment, days to treatment are equal to 1. If treatment will occur for more than 1 day, then the “days to treatment” value will change to 2 for the second day of treatment and so on (CT 12 and tau values should not be recalculated after the first day of treatment and times for each day of treatment should be determined prior).

Drug treatments. Treatment duration in this paradigm is either 1 or 3 days of injections, also termed pulses, at the intended CT for treatment (i.e., at one CT or multiple CTs), but 3 days of treatment has been shown to produce more robust effects of melatonin in rodents [46] and is in line with the corresponding protocol for studying effects of drug treatment on circadian phase in humans [46, 56].

To construct a phase response curve to melatonin ligands (e.g., agonists, inverse agonists), time of treatments with vehicle and drug of interest is planned at 2-h intervals (e.g., CT 0, 2, 4 , 6 , 8 , 10, 12 , 14, 16, 18, 20, 22). Treatments at particular CT can be centered around the desired time of injection to help with scheduling treatments around the clock. For example, if CT 10 is the desired time of injections, treatments should be as close as possible to the selected CT within a 2-h range (CT 9–CT 11). Data can be plotted as single points representing the shift in a single mouse or data can be grouped in 2-h bins and represented as a PRC [46, 59] (Fig. 2a, b).

Calculation of phase-shift: 2 weeks post treatment, data is analyzed using ClockLab analysis or related software to determine the actual CT 12 of each mouse on each injection day to ensure injection times were within the right time frame for the desired CT of administration and to determine the post treatment tau of wheel running activity onsets. Phase-shifts are quantified using the best-fit lines for onsets of activity during pre- and post treatment periods (7–14 days). Phase advances (post treatment onsets ahead of pretreatment onset best-fit line) (Fig. 3a) and phase delays (pretreatment onsets ahead of post treatment onset best-fit line) (Fig. 3b) of running wheel activity onset rhythms are used to define phase-shift direction. Activity onsets for the 3 days of treatments are excluded from the calculation of tau post treatment due to transient shifts in wheel running activity rhythms [78]. The actual shift is determined on the first day after the last treatment (Fig. 3a, b). To calculate the magnitude of the drug-induced phase-shifts when there is a slight change in tau, it is advisable to use the CT 12 of the day following final treatment due to large and inconsistent shifts that may arise from unparallel linear regression lines. Results are expressed as the number of minutes or hours phase-shifted across treatments and are compared to negative controls (i.e., vehicle) as well as positive controls (i.e., melatonin), depending on study design and data. See Notes 1 and 2 for information on recommendations for statistical analyses for phase-shift data.

Exclusion criteria for phase-shift actograms are (a) low running activity, sporadic activity, and/or missing activity; (b) tau change > 0.3 h; and (c) at least two out of three injections occurred outside of the target predetermined 2-h time range interval for treatment (e.g., CT 1–3, 5–7, 10–12).

Table 1.

Calculating clock time relative to circadian timing of running wheel activity

| Calculation of Clock Time vs. Circadian Time {CT 12 (adjusted) – [(24 – Pre-Tau) × Days to Treatment]} – [(CTT −CT 12) × (Pre-Tau/24)] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal ID (A) | Pre-Tau (B) | Present CT 12 (C) | Present CT 12 (Adjusted) (D) | |||

| 707 | 23.54 | 18.80 | 19.80 | |||

| Days to Treatment (E) | Day 1 (1) | Day 2 (2) | Day 3 (3) | |||

| CT Treatment (CTT) (h) | Decimal Time | Clock Time | Decimal Time | Clock Time | Decimal Time | Clock Time |

| CT 2 {D – [(24 – B) × E]} – (10 × (B/24)] | 9.53 | 9:31 AM | 9.07 | 9:04 AM | 8.61 | 8:36 AM |

| CT 10 {D – [(24 – B) × E]} – [2 × (B/24)] | 17.38 | 5:22 PM | 16.92 | 4:55 PM | 16.46 | 4.27 PM |

| CT 12 {D – [(24 – B) × E]} – [0 × (B/24)] | 19.34 | 7:20 PM | 18.88 | 6:52 PM | 18.42 | 6:25 PM |

Example of parameters and equations necessary to calculate the predicted clock time of melatonin receptor ligand treatment for a targeted CT (e.g., CT 2, CT 10, and CT 12) in the circadian phase-shift paradigm. Calculations are made 1 day prior to the first day of treatment using the free-running wheel activity tau or phase angle of at least 7 days of activity and the present CT 12 (onset of running wheel activity the day prior to the first treatment). The adjusted present CT 12 represents calculation for when the computer time is not in sync with the experimenter’s time (daylight savings time). The formula used is as follows:

B: Pre-tau

E: Number of days to treatment

CTT: Circadian time of target treatment

CT 12: Onset of activity adjusted for daylights saving time

3.2. Eastbound and Westbound Jet Lag Reentrainment Paradigm Protocols

This section will describe protocols to assess the efficacy of melatonin receptor ligands for their ability accelerate or decelerated re-entrainment to a new dark onset, in mice models of rhythmic behaviors. The two models simulate eastbound and westbound jet lag models in mice as previously described [35, 36, 53, 79].

Mice are group housed (4–5 per cage) and maintained in a 12/12 LD cycle for a period of 2 weeks with illuminance at the level of the cage floor maintained at 250–300 lux, before the start of an experiment. Mice are then transferred to cages equipped with running wheels (Fig. 1), immediately after lights off to prevent circadian phase-shifts associated with the presentation of novel running wheels [77].

For measuring drug-induced modulation of re-entrainment in a 12/12 LD cycle, mice placed on running wheels are next kept in a 12/12 LD cycle for 2 weeks or until a stable phase onset is achieved. Illuminance at the level of the cage floor should be maintained at 40–60 lux for the duration of the experiment. This will minimize the phase-shifting effect of light following an advance (light exposure during late portion of the dark period: ZT 20–24) or a delay (light exposure during early portion of the dark period: ZT 14–18) of dark onset. During this time, mice develop rhythmic wheel running activity patterns with high activity during the dark period and low activity during the light period.

Eastbound jet lag model: Following entrainment of mice to a 12/12 LD cycle, the dark onset is advanced by 6 h, resulting in a shortened photoperiod (short day) on the first day of the shift (Fig. 4a). Approximately 15–30 min prior to the new dark onset, depending on the number of mice to be treated, vehicle or drugs are administered for three consecutive days (Fig. 4a). Injections need to be completed before the new dark onset.

Westbound jet lag model: On the first day of treatment, the dark onset is delayed by 6 h, resulting in a shortened scotophase (short night). Vehicle or drug is administered for three consecutive days at the old dark onset approximately 15–30 min prior to the new dark, depending on the number of mice to be injected (Fig. 4b). This model poses two challenges: the masking effect of light on wheel running activity onsets [80] and light-mediated delays during the early subjective night [46, 47]. To overcome the masking effect of light on rhythmic activity, the re-entrainment rates and days to re-entrainment can be determined by analyzing the offsets of wheel running activity (J. Sosa and M.L.Dubocovich, unpublished). In the westbound re-entrainment model, treatments can alternatively be administered at the new dark onset [79].

Post treatment, mice are given 14–21 days to re-entrain to the new dark onset. Re-entrainment rate and days to reach re-entrainment depend on drug efficacy and the transgenic mouse used [35, 62, 63]. Melatonin receptor agonists accelerate re-entrainment and decrease the number of days to achieve re-entrainment when compared to vehicle, while an inverse agonist decelerates re-entrainment and increases the number of days to achieve re-entrainment (Fig. 5). Blockade of MT2 receptors endogenously activated by melatonin with a selective MT2 receptor antagonist [81] mimics genetic deletion of the MT2 receptor by decelerating re-entrainment of wheel running activity rhythms [62].

Activity onsets or offsets of wheel running activity rhythms are obtained using ClockLab or similar analysis software and exported as excel files. Excel can then be used to determine hours advanced or delayed each day by subtracting the daily activity onset or offset values from the average onset of wheel running activity calculated from the 3-day period (baseline) prior to treatment. These values are then used to calculate the rate of re-entrainment (e.g., hours advanced or delayed per day) and to determine days to re-entrainment, where the day corresponding to 6 ± 0.5 h of advancement or delay is defined as entrainment to the new LD cycle. Furthermore, this data is combined with visualization of actograms to verify the number of days for each mouse to reach stable re-entrainment. See Notes 1 and 2 for information on recommendations for statistical analyses for re-entrainment data.

Treatment in both the eastbound and westbound jet lag models could be made at other times during the 24-h light-dark cycle with potentially different outcomes depending on the status of the circadian system with respect to the light-dark cycle.

For re-entrainment, actograms exclusion criteria include (a) low or sporadic running activity, missing activity data, and/or lack of entrainment; (b) entrainment more than 1 h before or after the old or new dark onset; and (c) re-entrainment to the new dark onset before administration of the third treatment, which is likely attributed to the drug injection [35].

4. Notes

Statistical Analyses: Whenever possible, before determining group size for experiments, we recommend determination of statistical power a priori (α error probability = 0.05) based on data for a known effect size for melatonin or from preliminary data. All data sets should be visualized for normality using QQ plots of predicted vs. actual residuals and checked for violations of parametric statistical assumptions prior to running any analyses. Running wheel activity data should be generated blind to treatment prior to the quantification and statistical analysis stages. Data are analyzed according to the number of factors designed into the experiments such as number of treatments/drugs, genotype, and sex. In many cases, data from phase-shift experiments fit criteria for parametric statistical analyses, but we recommend verifying this for each data set as in some situations nonparametric tests are more appropriate (i.e., when data are not normally distributed or violate other assumptions of parametric analyses).

For determining the effect of drug treatment between mouse genotypes on the days to re-entrainment or the magnitude of phase-shift, we suggest using a two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test or Tukey’s post hoc test to detect differences between genotypes within each treatment group. Comparisons between drug treatments on days to re-entrainment or magnitude of phase-shift can be done using a one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test comparing drug treatments to vehicle controls. The rate of re-entrainment of wheel running activity rhythms can be analyzed using a repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, with Sidak’s multiple comparison post hoc test or a mixed-effects repeated measures two-way ANOVA if there are missing values.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the members of the Dubocovich Lab over the years that have contributed to the development and refinement of the methods and protocols described in this paper.

Funding Information

The development and refinement of the methods and protocols described in this paper were supported over the years by grants from the National Institute of Health including in recent years awards from the National Institute of Environmental Health Science [ES 023684 to MLD], from the National Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UL1TR001412 and KL2TR001413 to the University at Buffalo), and Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences unrestricted funds (to M.L.D.).

Abbreviations

- CT

Circadian time

- DD

Constant darkness

- LD

Light-dark cycle

- MT1

Melatonin receptor 1

- MT2

Melatonin receptor 2

- SCN

Suprachiasmatic nucleus

- ZT

Zeitgeber time

References

- 1.Tan DX, Hardeland R, Manchester LC et al. (2010) The changing biological roles of melatonin during evolution: from an antioxidant to signals of darkness, sexual selection and fitness. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 85:607–623. 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00118.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubocovich ML (2007) Melatonin receptors: role on sleep and circadian rhythm regulation. Sleep Med 8:34–42. 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubocovich ML, Rivera-Bermudez MA, Gerdin MJ et al. (2003) Molecular pharmacology, regulation and function of mammalian melatonin receptors. Front Biosci 8:d1093–d1108. 10.2741/1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubocovich ML, Markowska M (2005) Functional MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors in mammals. Endocrine 27:101–110. 10.1385/ENDO:27:2:101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jockers R, Delagrange P, Dubocovich ML et al. (2016) Update on melatonin receptors: IUPHAR review 20. Br J Pharmacol 173: 2702–2725. 10.1111/bph.13536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang C, Clough SJ, Adamah-Biassi EB et al. (2021) Impact of endogenous melatonin on rhythmic behaviors, reproduction, and survival revealed in melatonin-proficient C57BL/6J congenic mice. J Pineal Res:e12748. 10.1111/jpi.12748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kräuchi K, Cajochen C, Pache M et al. (2006) Thermoregulatory effects of melatonin in relation to sleepiness. Chronobiol Int 23: 475–484. 10.1080/07420520500545854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tarocco A, Caroccia N, Morciano G et al. (2019) Melatonin as a master regulator of cell death and inflammation: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications for newborn care. Cell Death Dis 10:317. 10.1038/s41419-019-1556-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reiter RJ (1991) Pineal melatonin: cell biology of its synthesis and of its physiological interactions. Endocr Rev 12:151–180. 10.1210/edrv-12-2-151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richter HG, Torres-Farfan C, Rojas-Garcia PP et al. (2004) The circadian timing system: making sense of day/night gene expression. Biol Res 37:11–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slominski A, Tobin DJ, Zmijewski MA et al. (2008) Melatonin in the skin: synthesis, metabolism and functions. Trends Endocrinol Metab 19:17–24. 10.1016/j.tem.2007.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukherjee S, Maitra SK (2015) Gut melatonin in vertebrates: chronobiology and physiology. Front Endocrinol 6:112. 10.3389/fendo.2015.00112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gern WA, Ralph CL (1979) Melatonin synthesis by the retina. Science 204:183–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turek FW, Gillette MU (2004) Melatonin, sleep, and circadian rhythms: rationale for development of specific melatonin agonists. Sleep Med 5:523–532. 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubocovich ML, Delagrange P, Krause DN et al. (2010) International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXV. Nomenclature, classification, and pharmacology of G protein-coupled melatonin receptors. Pharmacol Rev 62:343–380. 10.1124/pr.110.002832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams LM, Morgan PJ, Hastings MH et al. (1989) Melatonin receptor sites in the Syrian hamster brain and pituitary. Localization and characterization using [|]lodomelatonin*. J Neuroendocrinol 1:315–320. 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1989.tb00122.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reppert SM, Weaver DR, Ebisawa T (1994) Cloning and characterization of a mammalian melatonin receptor that mediates reproductive and circadian responses. Neuron 13: 1177–1185. 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90055-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masana MI, Benloucif S, Dubocovich ML (2000) Circadian rhythm of mt1 melatonin receptor expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the C3H/HeN mouse. J Pineal Res 28:185–192. 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2001.280309.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lacoste B, Angeloni D, Dominguez-Lopez S et al. (2015) Anatomical and cellular localization of melatonin MT1 and MT2 receptors in the adult rat brain. J Pineal Res 58:397–417. 10.1111/jpi.12224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klosen P, Lapmanee S, Schuster C et al. (2019) MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors are expressed in nonoverlapping neuronal populations. J Pineal Res:e12575. 10.1111/jpi.12575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peschke E, Fauteck JD, Musshoff U et al. (2000) Evidence for a melatonin receptor within pancreatic islets of neonate rats: functional, autoradiographic, and molecular investigations. J Pineal Res 28:156–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujieda H, Hamadanizadeh SA, Wankiewicz E et al. (1999) Expression of mt1 melatonin receptor in rat retina: evidence for multiple cell targets for melatonin. Neuroscience 93: 793–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scher J, Wankiewicz E, Brown GM et al. (2003) AII amacrine cells express the MT1 melatonin receptor in human and macaque retina. Exp Eye Res 77:375–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savaskan E, Jockers R, Ayoub M et al. (2007) The MT2 melatonin receptor subtype is present in human retina and decreases in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 4:47–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reppert SM, Godson C, Mahle CD et al. (1995) Molecular characterization of a second melatonin receptor expressed in human retina and brain: the Mel1b melatonin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:8734–8738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roca AL, Godson C, Weaver DR et al. (1996) Structure, characterization, and expression of the gene encoding the mouse Mel1a melatonin receptor. Endocrinology 137:3469–3477. 10.1210/endo.137.8.8754776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jockers R, Maurice P, Boutin JA et al. (2008) Melatonin receptors, heterodimerization, signal transduction and binding sites: what’s new? Br J Pharmacol 154:1182–1195. 10.1038/bjp.2008.184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cecon E, Oishi A, Jockers R (2017) Melatonin receptors: molecular pharmacology and signalling in the context of system bias. Br J Pharmacol 175:3263–3280. 10.1111/bph.13950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baba K, Benleulmi-Chaachoua A, Journe AS et al. (2013) Heteromeric MT1/MT2 melatonin receptors modulate photoreceptor function. Sci Signal:6:ra89. 10.1126/scisignal.2004302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerdin MJ, Masana MI, Ren D et al. (2003) Short-term exposure to melatonin differentially affects the functional sensitivity and trafficking of the hMT1 and hMT2 melatonin receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 304: 931–939. 10.1124/jpet.102.044990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stauch B, Johansson LC, McCorvy JD et al. (2019) Structural basis of ligand recognition at the human MT1 melatonin receptor. Nature 569:284–288. 10.1038/s41586-019-1141-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johansson LC, Stauch B, McCorvy JD et al. (2019) XFEL structures of the human MT2 melatonin receptor reveal the basis of subtype selectivity. Nature 569:289–292. 10.1038/s41586-019-1144-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kokkola T, Vaittinen M, Laitinen JT (2007) Inverse agonist exposure enhances ligand binding and G protein activation of the human MT1 melatonin receptor, but leads to receptor down-regulation. J Pineal Res 43:255–262. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00470.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roka F, Brydon L, Waldhoer M et al. (1999) Tight association of the human Mel(1a)-melatonin receptor and G(i): precoupling and constitutive activity. Mol Pharmacol 56: 1014–1024. 10.1124/mol.56.5.1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stein RM, Kang HJ, McCorvy JD et al. (2020) Virtual discovery of melatonin receptor ligands to modulate circadian rhythms. Nature 579: 609–614. 10.1038/s41586-020-2027-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Redman J, Armstrong S, Ng KT (1983) Free-running activity rhythms in the rat: entrainment by melatonin. Science 219:1089–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armstrong SM, Cassone VM, Chesworth MJ et al. (1986) Synchronization of mammalian circadian rhythms by melatonin. J Neural Transm Suppl 21:375–394 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cassone VM, Chesworth MJ, Armstrong SM (1986) Dose-dependent entrainment of rat circadian rhythms by daily injection of melatonin. J Biol Rhythm 1:219–229. 10.1177/074873048600100304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Redman JR, Armstrong SM (1988) Reentrainment of rat circadian activity rhythms: effects of melatonin. J Pineal Res 5:203–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kennaway DJ, Blake P, Webb HA (1989) A melatonin agonist and N-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynurenamine accelerate the reentrainment of the melatonin rhythm following a phase advance of the light-dark cycle. Brain Res 495:349–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sack RL, Lewy AJ, Blood ML et al. (1991) Melatonin administration to blind people: phase advances and entrainment. J Biol Rhythm 6:249–261. 10.1177/074873049100600305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warren WS, Hodges DB, Cassone VM (1993) Pinealectomized rats entrain and phase-shift to melatonin injections in a dose-dependent manner. J Biol Rhythm 8:233–245. 10.1177/074873049300800306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kennaway DJ (1994) Effect of a phase advance of the light/dark cycle on pineal function and circadian running activity in individual rats. Brain Res Bull 33:639–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Redman JR, Guardiola-Lemaitre B, Brown M et al. (1995) Dose dependent effects of S-20098, a melatonin agonist, on direction of re-entrainment of rat circadian activity rhythms. Psychopharmacology 118:385–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Drijfhout WJ, Homan EJ, Brons HF et al. (1996) Exogenous melatonin entrains rhythm and reduces amplitude of endogenous melatonin: an in vivo microdialysis study. J Pineal Res 20:24–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benloucif S, Dubocovich ML (1996) Melatonin and light induce phase shifts of circadian activity rhythms in the C3H/HeN mouse. J Biol Rhythm 11:113–125. 10.1177/074873049601100204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benloucif S, Masana MI, Yun K et al. (1999) Interactions between light and melatonin on the circadian clock of mice. J Biol Rhythm 14: 281–289. 10.1177/074873099129000696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arendt J, Skene DJ, Middleton B et al. (1997) Efficacy of melatonin treatment in jet lag, shift work, and blindness. J Biol Rhythm 12: 604–617. 10.1177/074873049701200616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Redman JR (1997) Circadian entrainment and phase shifting in mammals with melatonin. J Biol Rhythm 12:581–587. 10.1177/074873049701200613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klerman EB, Rimmer DW, Dijk DJ et al. (1998) Nonphotic entrainment of the human circadian pacemaker. Am J Phys 274(4 Pt 2): R991–R996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu J, Clough SJ, Hutchinson AJ et al. (2016) MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors: a therapeutic perspective. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 56:361–383. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dubocovich ML, Yun K, Al-Ghoul WM et al. (1998) Selective MT2 melatonin receptor antagonists block melatonin-mediated phase advances of circadian rhythms. FASEB J 12: 1211–1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dubocovich ML, Hudson RL, Sumaya IC et al. (2005) Effect of MT1 melatonin receptor deletion on melatonin-mediated phase shift of circadian rhythms in the C57BL/6 mouse. J Pineal Res 39:113–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lewy AJ, Bauer VK, Ahmed S et al. (1998) The human phase response curve (PRC) to melatonin is about 12 hours out of phase with the PRC to light. Chronobiol Int 15:71–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lewy AJ, Emens JS, Lefler BJ et al. (2005) Melatonin entrains free-running blind people according to a physiological dose-response curve. Chronobiol Int 22:1093–1106. 10.1080/07420520500398064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burgess HJ, Revell VL, Eastman CI (2008) A three pulse phase response curve to three milligrams of melatonin in humans. J Physiol 586: 639–647. 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jud C, Schmutz I, Hampp G et al. (2005) A guideline for analyzing circadian wheel-running behavior in rodents under different lighting conditions. Biol Proced Online 7: 101–116. 10.1251/bpo109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Glatfelter GC, Jones AJ, Rajnarayanan RV et al. (2021) Pharmacological actions of carbamate insecticides at mammalian melatonin receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 376:306–321. 10.1124/jpet.120.000065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rawashdeh O, Hudson RL, Stepien I et al. (2011) Circadian periods of sensitivity for ramelteon on the onset of running-wheel activity and the peak of suprachiasmatic nucleus neuronal firing rhythms in C3H/HeN mice. Chronobiol Int 28:31–38. 10.3109/07420528.2010.532894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Richardson GS, Zee PC, Wang-Weigand S et al. (2008) Circadian phase-shifting effects of repeated ramelteon administration in healthy adults. J Clin Sleep Med 4:456–461 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cassone VM, Chesworth MJ, Armstrong SM (1986) Entrainment of rat circadian rhythms by daily injection of melatonin depends upon the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nuclei. Physiol Behav 36:1111–1121. 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90488-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pfeffer M, Rauch A, Korf HW et al. (2012) The endogenous melatonin (MT) signal facilitates reentrainment of the circadian system to light-induced phase advances by acting upon MT2 receptors. Chronobiol Int 29:415–429. 10.3109/07420528.2012.667859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pfeffer M, Korf HW, Wicht H (2017) Synchronizing effects of melatonin on diurnal and circadian rhythms. Gen Comp Endocrinol 258: 215–221. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2017.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lewy AJ, Ahmed S, Jackson JM et al. (1992) Melatonin shifts human circadian rhythms according to a phase-response curve. Chronobiol Int 9:380–392. 10.3109/07420529209064550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Siepka SM, Takahashi JS (2005) Methods to record circadian rhythm wheel running activity in mice. Methods Enzymol 393:230–239. 10.1016/s0076-6879(05)93008-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuljis DA, Loh DH, Truong D et al. (2013) Gonadal- and sex-chromosome-dependent sex differences in the circadian system. Endocrinology 154:1501–1512. 10.1210/en.2012-1921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hattar S, Lucas RJ, Mrosovsky N et al. (2003) Melanopsin and rod-cone photoreceptive systems account for all major accessory visual functions in mice. Nature 424:76–81. 10.1038/nature01761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takahashi JS, DeCoursey PJ, Bauman L et al. (1984) Spectral sensitivity of a novel photoreceptive system mediating entrainment of mammalian circadian rhythms. Nature 308: 186–188. 10.1038/308186a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goto M, Ebihara S (1990) The influence of different light intensities on pineal melatonin content in the retinal degenerate C3H mouse and the normal CBA mouse. Neurosci Lett 108:267–272. 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90652-p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goto M, Oshima I, Tomita T et al. (1989) Melatonin content of the pineal gland in different mouse strains. J Pineal Res 7:195–204. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1989.tb00667.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Refinetti R (2015) Comparison of light, food, and temperature as environmental synchronizers of the circadian rhythm of activity in mice. J Physiol Sci 65:359–366. 10.1007/s12576-015-0374-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stephan FK (1986) Interaction between lightand feeding-entrainable circadian rhythms in the rat. Physiol Behav 38:127–133. 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90142-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stephan FK (1986) Coupling between feeding- and light-entrainable circadian pacemakers in the rat. Physiol Behav 38:537–544. 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90422-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stephan FK (1986) The role of period and phase in interactions between feeding- and light-entrainable circadian rhythms. Physiol Behav 36:151–158. 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90089-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Van Reeth O, Olivares E, Zhang Y et al. (1997) Comparative effects of a melatonin agonist on the circadian system in mice and Syrian hamsters. Brain Res 762:185–194. 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00382-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hablitz LM, Molzof HE, Abrahamsson KE et al. (2015) GIRK channels mediate the nonphotic effects of exogenous melatonin. J Neurosci 35:14957–14965. 10.1523/jneurosci.1597-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Janik D, Godfrey M, Mrosovsky N (1994) Phase angle changes of photically entrained circadian rhythms following a single nonphotic stimulus. Physiol Behav 55:103–107. 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90016-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dunlap JC, Loros JL, DeCoursey PJ (2004) Chronobiology: biological timekeeping. Sina Assoc 3:67–105 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Singaravel M, Sharma VK, Subbaraj R et al. (1996) Chronobiotic effect of melatonin following phase shift of light/dark cycles in the field mouseMus booduga. J Biosci 21: 789–795. 10.1007/BF02704720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Refinetti R (2002) Compression and expansion of circadian rhythm in mice under long and short photoperiods. Integr Physiol Behav Sci 37:114–127. 10.1007/bf02688824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sosa J, Lipinski J, Tsakalidou V et al. (2021) Selective MT2 melatonin receptor antagonist modulates circadian activity via inhibition of the endogenous melatonin signal in the east bound jet lag model. FASEB J 35(S1). 10.1096/fasebj.2021.35.S1.01911 [DOI] [Google Scholar]