Abstract

Background

Anthracycline chemotherapies cause heart failure in a subset of cancer patients. We previously reported that the anthracycline doxorubicin (DOX) induces cardiotoxicity through the activation of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2).

Objectives

The aim of this study was to determine whether retinoblastoma-like 2 (RBL2/p130), an emerging CDK2 inhibitor, regulates anthracycline sensitivity in the heart.

Methods

Rbl2−/− mice and Rbl2+/+ littermates received DOX (5 mg/kg/wk for 4 weeks intraperitoneally, 20 mg/kg cumulative). Heart function was monitored with echocardiography. The association of RBL2 genetic variants with anthracycline cardiomyopathy was evaluated in the SJLIFE (St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study) and CPNDS (Canadian Pharmacogenomics Network for Drug Safety) studies.

Results

The loss of endogenous Rbl2 increased basal CDK2 activity in the mouse heart. Mice lacking Rbl2 were more sensitive to DOX-induced cardiotoxicity, as evidenced by rapid deterioration of heart function and loss of heart mass. The disruption of Rbl2 exacerbated DOX-induced mitochondrial damage and cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Mechanistically, Rbl2 deficiency enhanced CDK2-dependent activation of forkhead box O1 (FOXO1), leading to up-regulation of the proapoptotic protein Bim. The inhibition of CDK2 desensitized Rbl2-depleted cardiomyocytes to DOX. In wild-type cardiomyocytes, DOX exposure induced Rbl2 expression in a FOXO1-dependent manner. Importantly, the rs17800727 G allele of the human RBL2 gene was associated with reduced anthracycline cardiotoxicity in childhood cancer survivors.

Conclusions

Rbl2 is an endogenous CDK2 inhibitor in the heart and represses FOXO1-mediated proapoptotic gene expression. The loss of Rbl2 increases sensitivity to DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. Our findings suggest that RBL2 could be used as a biomarker to predict the risk of cardiotoxicity before the initiation of anthracycline-based chemotherapy.

Key Words: cancer therapy, cardiomyopathy, cardiotoxicity, cell cycle, cell death, doxorubicin, genetics, heart failure, mechanisms, tumor

Central Illustration

The cancer survivor population has been increasing rapidly over the past decades, reaching 16.9 million in the United States alone.1 Cancer survivors are at an ∼10-fold higher risk of developing cardiomyopathy and heart failure because of the widespread use of cardiotoxic cancer therapies.2 As the cornerstone of many chemotherapy regimens, anthracyclines cause heart failure in a subset of patients (ranging from 3% to 48%) depending on the cumulative dose.2 Interestingly, even with the same dose of anthracyclines, there is substantial interindividual variability in the risk of cardiotoxicity.3 At present, very little is known about the factors that determine cardiac sensitivity to chemotherapy (ie, chemosensitivity). Recent studies reveal that the SLC28A3 rs7853758, RARG rs2229774, and UGT1A6 rs17863783 genetic variants are associated with anthracycline-related cardiotoxicity.4, 5, 6, 7 Thus, screening for these genetic variants has been recommended as a promising strategy for the identification of at-risk individuals.8 The investigation of additional genetic factors may help enhance the risk prediction of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity.

Apoptotic death of cardiomyocytes contributes to anthracycline-related cardiac injury.9 Our recent findings suggest that the anthracycline doxorubicin (DOX) induces cardiomyocyte apoptosis through the activation of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2).10, 11, 12, 13 CDK2 directly interacts with retinoblastoma (RB)-like 2 (RBL2/p130),14 which functions as a CDK2 inhibitor in vitro.15,16 However, it remains unclear whether RBL2 inhibits CDK2 activity in vivo and regulates the myocardial response to anthracyclines.

RBL2, together with RB1/p105 and RBL1/p107, belongs to the RB protein family, which is primarily known for inhibiting G1/S cell-cycle transition.17 In the adult mouse heart, Rb1 and Rbl2 are the predominant RB proteins and play overlapping roles in maintaining the postmitotic state of cardiomyocytes.18,19 The inhibition of Rb1 promotes cardiomyocyte cell-cycle re-entry and apoptosis after myocardial ischemia.20, 21, 22 Recently, sequence variations of RBL2 have been associated with various pathological disorders,23, 24, 25, 26 indicating a potential role of RBL2 in disease development. We most recently demonstrated that ablation of the Rbl2 gene in mice aggravates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury.27 The primary objective of our current study was to determine whether Rbl2 regulates cardiac sensitivity to DOX-induced injury. Our main findings from primary cardiomyocytes and mouse models were further validated in cohort studies of cancer patients and survivors.

Materials and Methods

Additional methods can be found in the Supplemental Methods.

Experimental animals

Rbl2−/− mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Stock No. 008176) are fertile with no discernible abnormalities.28 Rbl2−/− mice were crossed with C57BL/6 mice (Envigo) to generate Rbl2 heterozygotes (Rbl2+/−), which were then intercrossed to obtain Rbl2−/− mice and wild-type (Rbl2+/+) littermates. Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Envigo. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Washington State University and were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edition).

In vivo studies

Rbl2−/− and Rbl2+/+ mice (8-12 weeks old, male) received injections of DOX (5 mg/kg/wk for 4 weeks intraperitoneally, LC Laboratories) or saline. Heart function was examined weekly under anesthesia by echocardiography using the VisualSonics VEVO 2100 imaging system. Animals were sacrificed at 6 weeks after the first DOX injection. Myocardial fibrosis was assessed with Masson’s trichrome staining. To determine the effect of forkhead box O1 (FOXO1) inhibition on Rbl2 expression, C57BL/6 mice (8-12 weeks old, male) received DOX (5 mg/kg/wk for 4 weeks intraperitoneally) as well as the FOXO1 inhibitor AS1842856 (100 mg/kg, oral gavage, twice daily for 2 days immediately after each DOX injection) or a carrier control (6% [2-hydroxypropyl]-β-cyclodextrin) as described previously.12,29 Mice were sacrificed at 24 hours after the first DOX injection or 2 weeks after the last DOX injection.

Study cohorts of cancer survivors and patients

SJLIFE (St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study) enrolls survivors of childhood cancer treated at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital who have survived ≥5 years after diagnosis on a protocol for longitudinal follow-up approved by the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Institutional Review Board.30 Childhood cancer survivors of European ancestry previously treated with anthracycline chemotherapy (N = 1,975) were included in this study. Cardiomyopathy was graded according to a modified version of the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.03 (grades 1 [mild], 2 [moderate], 3 [severe or disabling], 4 [life-threatening], or 5 [fatal]) as described recently.30

CPNDS (Canadian Pharmacogenomics Network for Drug Safety) enrolls patients with adverse drug reactions for genomic studies, which are approved by the Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia. Enrolled patients include children with cancer who are undergoing treatment or long-term follow-up (N = 272). Cardiotoxicity was defined as fractional shortening (FS) ≤24% by echocardiography at least 21 days after an anthracycline dose to avoid transient effects on left ventricular function.

Statistical analysis

Prism 7.02 (GraphPad Software) was used for statistical analysis. The results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Normality was determined using the Shapiro-Wilk test and/or visualizing data distribution as appropriate. Although the standard sample size in experimental biology (n < 20) precludes a reliable normality test,31 plots of the data showed no apparent indication of data skew. Differences between the 2 groups were compared using the 2-tailed Student’s t-test. Differences between multiple groups were analyzed using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey post hoc test for multiple pairwise comparisons or repeated measures or ordinary 2-way ANOVA followed by the Sidak post hoc test as appropriate. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Cardiomyopathy association in the SJLIFE cohort

rs17800727 is a common variant (Supplemental Table 1), and its association with cardiomyopathy was evaluated with logistic regression. The other variants (rs76818213, rs61747629, rs140896175, rs61747628, and rs199555150) are rare (Supplemental Table 1) and were jointly tested using the optimized sequence kernel association test.32 All analyses were adjusted for age at childhood cancer diagnosis, sex, chest radiation, cumulative anthracycline dose, and age at last contact. Associations were examined for Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grade 3 to 4 cardiomyopathy.

Cardiotoxicity association in the CPNDS cohort

rs17800727 was evaluated through logistic regression under an additive genetic model comparing cases with cardiotoxicity to controls (FS ≥30% during and at the end of anthracycline treatment). Analyses were adjusted for age at the start of treatment, cumulative anthracycline dose, tumor type, and cardiac radiation therapy. The results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs.

Results

Loss of Rbl2 provoked cardiac CDK2 activation in vitro and in vivo

Rbl2 has emerged as an endogenous CDK2 inhibitor in some contexts.15,16 To determine whether Rbl2 inhibits cardiac CDK2 activity, neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCMs) were transfected with Rbl2 small interfering RNA or a nontargeting control. As shown in Figure 1A, knockdown of Rbl2 significantly increased the protein level of phospho-CDK2 (T160), a reliable marker for CDK2 kinase activation.11 We recently reported that CDK2 activation augments the expression of Bim, a BH3-only protein involved in the initiation of the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway.11 Indeed, the depletion of Rbl2 significantly upregulated the Bim protein in cultured cardiomyocytes (Figure 1A). Immunofluorescent staining further revealed that silencing of Rbl2 increased the signal intensity of phospho-CDK2 (T160, Figure 1B) and Bim (Figure 1C). In agreement with our in vitro data, the loss of Rbl2 significantly increased the protein levels of phospho-CDK2 (T160) and Bim in the mouse heart (Figure 1D). Phospho-CDK2 (T160) was primarily localized in the nuclei of cardiomyocytes and was increased by Rbl2 ablation (Figure 1E). Taken together, these results suggested that Rbl2 loss increased cardiac CDK2 activity.

Figure 1.

Loss of Rbl2 Provoked Cardiac CDK2 Activation

(A) Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCMs) were transfected with control (siControl) or Rbl2 siRNA (siRbl2), and protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting (n = 3-4). The 2-tailed Student’s t test. ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. siControl. (B) Immunofluorescent staining for phospho–cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) (T160, green), cardiac troponin T (cTnT, red) and nuclei (4ʹ,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole [DAPI], blue). Fluorescence intensity of phospho-CDK2 (T160) was increased in Rbl2-depleted cardiomyocytes. Scale bar = 10μm. (C) Immunofluorescent staining for Bim (green), cTnT (red), and nuclei (blue). Fluorescence intensity of Bim was also increased in Rbl2-depleted cardiomyocytes. Scale bar = 10μm. (D) Heart protein lysates isolated from adult male germline Rbl2 null mice (Rbl2–/–) or wild-type littermates (Rbl2+/+) were immunoblotted using indicated antibodies (n = 3-4 per group). The 2-tailed Student’s t test. ∗∗P < 0.01 vs Rbl2+/+. (E) Heart tissue sections from adult male Rbl2+/+ and Rbl2−/− mice were stained for phospho-CDK2 (T160, green), cTnT (red), and nuclei (DAPI, blue). Fluorescence intensity of phospho-CDK2 (T160) was increased in Rbl2-deficient cardiomyocytes. Scale bar = 10 μm. GAPDH = glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Cardiomyocytes lacking Rbl2 were sensitive to DOX-induced mitochondrial apoptosis

Based on our findings that CDK2 activation is necessary for DOX-induced apoptosis,11 we hypothesized that Rbl2 deficiency primes cardiomyocytes for apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway. In response to the DOX challenge, silencing of Rbl2 significantly increased the JC-1 monomer/J-aggregate ratio (Figure 2A), indicating increased mitochondrial susceptibility to damage. Moreover, knockdown of Rbl2 also increased terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling–positive cells (Figure 2B) and cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (Figure 2C), 2 widely used markers of apoptosis. Therefore, the depletion of Rbl2 sensitized cardiomyocytes to DOX-induced mitochondrial damage and apoptosis.

Figure 2.

Cardiomyocytes Lacking Rbl2 Were Sensitive to DOX-Induced Mitochondrial Apoptosis

(A) Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCMs) were transfected with siRbl2 before incubation with doxorubicin (DOX) (1 μmol/L) for 24 hours (n = 3). Cells were then incubated with JC-1 to label healthy (J-aggregates, red) and damaged mitochondria (JC-1 monomers, green). The depletion of Rbl2 exacerbated DOX-induced mitochondrial damage. Scale bar = 100 μm. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Sidak post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. (B) NRCMs transfected with siControl or siRbl2 were treated with DOX (1 μmol/L) for 24 hours (n = 3). Apoptosis was measured by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining. Two-way ANOVA with the Sidak post hoc test. ∗∗∗P < 0.001. (C) NRCMs were transfected with siControl or siRbl2 before treatment with DOX (1 μmol/L) for 24 hours (n = 5). Protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting. The 2-tailed Student t test. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs siControl. PARP = poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Rbl2 deficiency accelerated cardiac dysfunction after DOX administration in mice

Apoptotic death of cardiomyocytes is a potential cause of anthracycline-induced myocardial injury.9 To determine whether Rbl2 deficiency increases cardiac chemosensitivity in vivo, Rbl2 null mice and wild-type littermates were challenged with DOX (5 mg/kg/wk for 4 weeks) (Figure 3A). Despite comparable heart function at baseline, Rbl2 deficiency markedly accelerated DOX-induced cardiac dysfunction as revealed by rapid declines of ejection fraction (EF) (Figure 3B) and FS (Figure 3C) starting at 1 week after the first DOX injection. In contrast, EF and FS in wild-type mice were not significantly reduced until week 4 (Figures 3B and 3C). At week 3, ablation of Rbl2 significantly reduced EF and FS (Figures 3B and 3C), increased left ventricular end-systolic volume (Figure 3D), and reduced posterior wall thicknesses (Figure 3E, Supplemental Table 2). As a control, 4 weekly injections of saline failed to alter heart function in either Rbl2 null or wild-type mice (Supplemental Figure 1). Masson’s trichrome staining revealed that Rbl2 deficiency significantly augmented DOX-induced cardiac fibrosis (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Rbl2 Deficiency Accelerated Cardiac Dysfunction After DOX Administration in Mice

(A) DOX injection protocol. Germline Rbl2 null mice (Rbl2−/−) and wild-type littermates (Rbl2+/+) received serial injections of DOX (5 mg/kg/wk for 4 weeks intraperitoneally, n = 10-12 per group). (B-E) Heart function was assessed weekly using echocardiography. (B) Ejection fraction (EF) and (C) fractional shortening (FS). Repeated measures 2-way ANOVA with the Sidak post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs Rbl2−/− time 0, #P < 0.05 vs Rbl2+/+ time 0, $$P < 0.01, $$$P < 0.001 vs Rbl2+/+ at the same time point. (D) Left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVVs) was significantly increased in Rbl2−/− mice at week 3. (E) Left ventricular posterior wall thickness at end-systole (LVPWs) was significantly reduced in Rbl2−/− mice at week 3. Two-way ANOVA with the Sidak post hoc test. ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. (F) Myocardial fibrosis was evaluated by Masson’s trichrome staining (n = 4-5 per group). Scale bar = 50 μm. Two-way ANOVA with the Sidak post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05. Abbreviations as in Figure 2.

Mice lacking Rbl2 were sensitive to DOX-induced heart weight loss and cardiomyocyte apoptosis

Anthracycline administration can reduce heart mass in cancer patients within months.33,34 At 3 weeks after the first DOX injection, Rbl2 null but not wild-type mice already exhibited a significant reduction in left ventricular mass as evaluated by echocardiography (Figure 4A). At week 6, a DOX-induced decrease in heart weight/tibia length ratio was more pronounced in Rbl2 null mice than in wild-type mice (Figure 4B). DOX injection also reduced the cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area, but surprisingly no difference was detected between wild-type and Rbl2 null hearts (Figure 4C). Intriguingly, a DOX-induced increase in terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling–positive cells was markedly augmented by Rbl2 ablation (Figure 4D). These data suggested that Rbl2 null mice were more sensitive to DOX-induced heart weight loss, likely because of increased cardiomyocyte loss through apoptosis.

Figure 4.

Rbl2 Deficiency Exacerbated DOX-Induced Heart Weight Loss Via Apoptosis

(A) Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular (LV) mass before and at 3 weeks after the first DOX injection (n = 9-12 per group). Two-way ANOVA with the Sidak post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05. (B) Heart weight/tibia length ratio at 6 weeks after the first DOX injection was normalized to saline control for each genotype (n = 9-12 per group). Two-way ANOVA with the Sidak post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. (C) The cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area at 6 weeks after the first DOX injection was evaluated by wheat germ agglutinin staining (n = 4-5 per group). Two-way ANOVA with the Sidak post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05. (D) Cardiomyocyte apoptosis at 6 weeks after the first DOX injection was measured by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining (n = 4-6 per group). Two-way ANOVA with the Sidak post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. Abbreviations as in Figure 2.

Depletion of Rbl2 enhanced DOX-induced activation of the proapoptotic CDK2-FOXO1-Bim axis

We next determined whether Rbl2 depletion exacerbated DOX-induced apoptosis through the activation of CDK2. In the presence of DOX, knockdown of Rbl2 increased protein levels of phospho-CDK2 (T160), Bim, and cleaved PARP (Figure 5A), indicating increased CDK2 activation and apoptosis. Treatment with the CDK inhibitor roscovitine abolished the upregulation of phospho-CDK2 (T160), Bim, and cleaved PARP caused by Rbl2 depletion (Figure 5A). Conversely, overexpression of Rbl2 reduced phospho-CDK2 (T160) and Bim levels after treatment with DOX (Figure 5B), suggesting that Rbl2 inhibited CDK2-dependent Bim expression. We recently reported that CDK2 phosphorylates FOXO1 at S249 to activate FOXO1-mediated Bim transcription.12 Interestingly, the depletion of Rbl2 significantly enhanced DOX-induced FOXO1 phosphorylation at S249 (Figure 5C). Moreover, pretreatment with a FOXO1 inhibitor, AS1842856, reduced Bim level and abolished Bim upregulation caused by Rbl2 depletion (Figure 5D). Together these results suggested that Rbl2 deficiency increased DOX sensitivity through uncontrolled activation of the CDK2-FOXO1-Bim axis.

Figure 5.

Rbl2 Depletion Enhanced DOX-Induced CDK2-FOXO1-Bim Activation

(A) NRCMs transfected with siControl or siRbl2 were incubated with DOX (1 μmol/L) for 24 hours (n = 3) with or without the pharmacologic CDK2 inhibitor roscovitine (50 μmol/L). Protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting. Two-way ANOVA with the Sidak post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. (B) NRCMs were infected with green fluorescent protein adenovirus (AdGFP) or human RBL2 adenovirus (AdRBL2) before treatment with DOX (1 μmol/L) for 24 hours (n = 3). Protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting. The 2-tailed Student’s t-test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs AdGFP. (C) NRCMs were transfected with siRbl2 before incubation with DOX (1 μmol/L) for 4 hours (n = 3). Protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting. Two-way ANOVA with the Sidak post hoc test. ∗∗∗P < 0.001. (D) NRCMs transfected with siControl or siRbl2 were incubated with DOX (1 μmol/L) for 4 hours (n = 3) with or without the pharmacologic forkhead box O1 (FOXO1) inhibitor AS1842856 (1 μmol/L). Protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting. Two-way ANOVA with the Sidak post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. NS = not significant; Abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 2.

DOX exposure induced FOXO1-dependent cardiac Rbl2 expression

Because FOXO1 has also been shown to mediate the transcription of RBL2,35 we next investigated whether DOX induces Rbl2 expression in cardiomyocytes. Indeed, treatment with DOX transiently increased the Rbl2 protein level in NRCMs (Figure 6A). Subcellular fractionation further revealed that DOX increased the Rbl2 protein predominantly in the nuclei of cardiomyocytes (Figure 6B). DOX treatment also transiently increased Rbl2 messenger RNA level (Figure 6C). In contrast, DOX exposure reduced Rbl2 protein half-life from 33.3h to 10.9h (Supplemental Figure 2), suggesting that DOX reduced Rbl2 protein stability. Therefore, DOX treatment transiently upregulated the Rbl2 protein primarily through an increase in Rbl2 messenger RNA. DOX-induced Rbl2 expression was blocked by the FOXO1 inhibitor AS1842856 (Figure 6D), suggesting that DOX induced Rbl2 expression through the activation of FOXO1. In agreement with our previous findings that myocardial FOXO1 activity is increased at 24 hours after DOX injection,12 DOX also significantly increased the Rbl2 protein level in mice hearts (Figure 6E). Importantly, oral administration of AS1842856 reduced the cardiac Rbl2 protein level at 24 hours after DOX injection (Figure 6F). Downregulation of myocardial Rbl2 expression by AS1842856 was also observed in a chronic DOX model (5 mg/kg/wk for 4 weeks) (Supplemental Figure 3). Collectively, our findings suggested that DOX induced FOXO1-mediated transcription of Rbl2, which in turn inhibited the CDK2-FOXO1 axis through a negative feedback loop.

Figure 6.

DOX Exposure Induced FOXO1-Dependent Cardiac Rbl2 Expression

(A) NRCMs were incubated with DOX (1 μmol/L) for various periods of time (n = 3). Protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting. One-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 vs time 0. (B) Subcellular fractionation of NRCMs incubated with DOX (1 μmol/L) for 0, 4, or 24 hours (n = 3). Protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting, with histone H3 and GAPDH as nuclear and cytosolic loading controls, respectively. One-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. ∗∗P < 0.01 vs time 0. (C) NRCMs were incubated with DOX (1 μmol/L) for 0, 4, or 24 hours, and the Rbl2 transcript level was evaluated by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, with18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) as an internal control (n = 3). One-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. ∗ P< 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs time 0. (D) NRCMs were treated with DOX (1 μmol/L) for 4 hours with or without the FOXO1 inhibitor AS1842856 (1 μmol/L, n = 6). Protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting. Two-way ANOVA with the Sidak post hoc test. ∗∗P < 0.01. (E) Adult hearts were harvested at 24 hours after saline or DOX injection (5 mg/kg intraperitoneally, n = 3 per group). Protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting. The 2-tailed Student’s t-test. ∗P < 0.05 vs saline. (F) Adult hearts were harvested at 24 hours after a single DOX injection (5 mg/kg intraperitoneally), with oral administration of carrier control or the FOXO1 inhibitor AS1842856 (100 mg/kg, twice daily, n = 4 per group). The 2-tailed Student’s t-test. ∗ P < 0.05 vs carrier. Abbreviations as in Figures 1, 2, and 5.

The rs17800727 G allele of RBL2 gene was associated with reduced risk of anthracycline cardiotoxicity in humans

The human RBL2 gene has 6 missense variants with allele frequency >0.1% (Supplemental Table 1). Among the 6 variants, rs17800727 (A>G) is the most common one (minor allele frequency = 21.2%). Interestingly, expression quantitative trait locus analysis revealed that the G allele of rs17800727 was significantly associated with lower RBL2 expression in the left ventricle (P = 2.3 × 1014, normalized effect size = −0.21) (Figure 7A) as well as in other organs (Supplemental Figure 4). We then tested the potential association between rs17800727 and anthracycline cardiotoxicity in the SJLIFE cancer survivors of European ancestry who had received anthracyclines. The minor allele G of rs17800727 was significantly associated with a decreased risk of grade 3 to 4 cardiomyopathy (OR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.52-0.99; P = 0.042) (Table 1). Individuals homozygous for the G allele were at the lowest risk of grade 3 to 4 cardiomyopathy compared with those with AG and AA (OR: 0.30; 95% CI: 0.10-0.87; P = 0.026) (Table 1). In other words, individuals homozygous for the A allele were at the highest risk for grade 3 to 4 cardiomyopathy compared with those with the GG genotype (OR: 3.33; 95% CI: 1.15-10.00). The other 5 variants were not significantly associated with grade 3 to 4 cardiomyopathy (P = 0.33).

Figure 7.

Genetic Variation rs17800727 Alters RBL2 Expression in Human Heart

Left ventricular RBL2 expression quantitative trait locus violin plot for rs17800727 was obtained from the GTEx database. The white line in the box plot indicates the median value of RBL2 expression. The number under each genotype indicates the sample size. The G allele is associated with lower RBL2 expression than the A allele. NES = normalized effect size.

Table 1.

Association of rs17800727 (A>G) With Cardiomyopathy in the SJLIFE Cohort

| Cardiomyopathy | Cases (N) | Minor allele | OR (95% CI) | P Value | Genotypes | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 3-4 | 120 | G | 0.71 (0.52-0.99) | 0.042 | AG | 0.86 (0.57-1.29) | 0.46 |

| GG | 0.30 (0.10-0.87) | 0.026 |

Cardiomyopathy was graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.03 criteria.

OR = odds ratio; SJLIFE = St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study.

We next examined the association between rs17800727 and anthracycline cardiotoxicity in the CPNDS cohort that enrolled pediatric cancer patients. The G allele was associated with a reduced risk of anthracycline cardiotoxicity (OR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.37-1.48; P = 0.39) (Table 2). However, the difference did not reach statistical significance, possibly because of the relatively small sample size (only 13 of the 31 patients with cardiotoxicity carried this variant).

Table 2.

Association of rs17800727 (A>G) With Cardiotoxicity in the CPNDS Cohort

| Cardiotoxicity | Cases (n) | Minor allele | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FS ≤24% | 31 | G | 0.74 (0.37-1.48) | 0.39 |

CPNDS = Canadian Pharmacogenomics Network for Drug Safety; FS = fractional shortening; OR = odds ratio.

Discussion

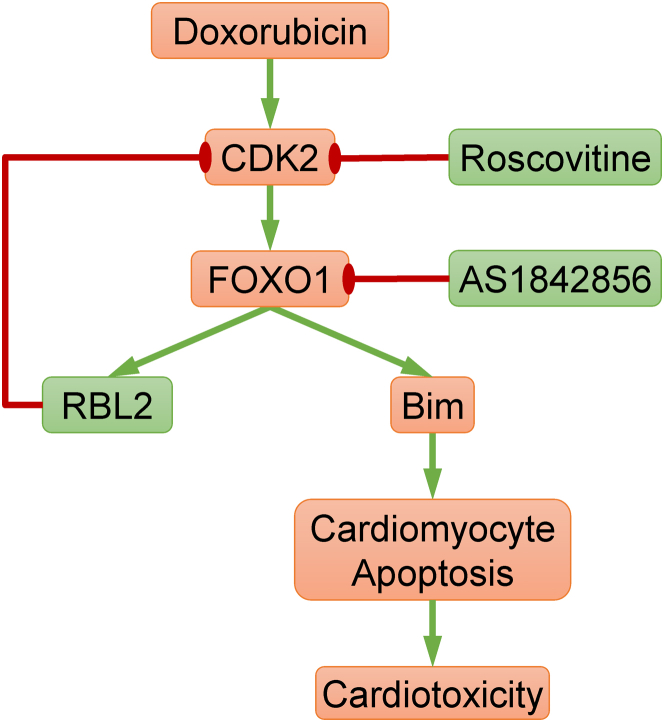

Anthracyclines are known to induce myocardial injury by interfering with topoisomerase IIβ activity and resulting in DNA damage.36 In line with previous findings that DNA damage activates CDK2,37,38 we recently reported that the proapoptotic CDK2-FOXO1-Bim axis mediates DOX cardiotoxicity.10, 11, 12, 13 In the present study, we demonstrated that the loss of Rbl2 provoked activation of the CDK2-FOXO1-Bim axis, leading to increased DOX cardiotoxicity (Figure 8, Central Illustration). Interestingly, DOX also induces FOXO1-mediated expression of Rbl2, which may represent an adaptive response that protects against cardiomyocyte injury. Despite the potential cardioprotection by FOXO1-mediated Rbl2 expression, FOXO1 activation appears to show a deleterious net effect on DOX cardiotoxicity, at least in part, through mediating Bim expression.12 Recent evidence suggests that preferential binding of FOXO1 with specific target promoters can be modulated by homo- or heterodimerization.39,40 Thus, it is interesting to investigate whether it is possible to steer FOXO1 from Bim promoter to Rbl2 promoter after DOX exposure in future studies.

Figure 8.

The Role of RBL2 in Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity

The anthracycline DOX induces CDK2-dependent FOXO1 activation, leading to the transcription of Bim and RBL2. Although Bim mediates cardiomyocyte apoptosis and cardiotoxicity, RBL2 provides feedback inhibition of CDK2. Therefore, the loss of RBL2 causes uncontrolled Bim transcription, resulting in aggravated cardiotoxicity. Pharmacologic inhibitors of CDK2 (roscovitine) or FOXO1 (AS1842856) may promote resistance against DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. Abbreviations as in Figures 1, 2, and 5.

Central Illustration.

RBL2 Regulates Cardiac Sensitivity to Anthracyclines

Compared with wild-type controls, mice lacking Rbl2 are more sensitive to anthracycline cardiotoxicity because of increased cyclin-dependent kinase 2 activity and apoptosis. In humans, individuals homozygous for the RBL2 gene G allele were at the lowest risk of grade 3 to 4 cardiomyopathy compared with those with AG and AA (odds ratio [OR]: 0.30; 95% CI: 0.10-0.87). The rs17800727 A allele (homozygous) was associated with an increased risk of anthracycline cardiotoxicity (OR: 3.33; 95% CI: 1.15-10.00). Our findings suggest that RBL2 genetic variation may be used to predict the risk of anthracycline cardiotoxicity.

Our data revealed that genetic ablation of Rbl2 increased DOX-induced cardiotoxicity in mice. Intriguingly, patients with the minor G allele of rs17800727 were resistant to anthracycline cardiotoxicity despite the lower RBL2 levels. Because RBL2 expression is mediated by the CDK2-FOXO1 axis (Figure 8), we speculate that the rs17800727 G allele may result in lower CDK2-FOXO1 activity than the A allele. In support of this speculation, the inhibition of CDK2-FOXO1 activity attenuates DOX-induced cardiotoxicity in mice.11,12 Because ablation of Rbl2 enhanced CDK2-FOXO1 activation in mice, the effect of Rbl2 gene variation on DOX cardiotoxicity may depend on CDK2-FOXO1 activity. Future studies are needed to investigate whether rs17800727 regulates CDK2 or FOXO1 activity.

It has been shown that the RBL2 spacer domain directly binds CDK2 and inhibits its kinase activity.15 Indeed, a 39-amino-acid peptide (Spa310, aa 641-679) derived from the RBL2 spacer domain represses CDK2 activity, resulting in cell-cycle arrest at G0/G1.41 In the current study, we showed that cardiomyocyte CDK2 activity was increased by the deletion of Rbl2 but decreased by the overexpression of Rbl2. In line with our results, combined deletion of Rbl2 and Rb1 dramatically increases cardiac CDK2 activity.18 Collectively, these findings suggest that Rbl2 may be a novel, endogenous CDK2 inhibitor in the heart.

RBL2 may also regulate DOX cardiotoxicity through CDK2-independent mechanisms. For example, RBL2 can transport E2F4 to the nucleus to repress gene transcription.17 The overexpression of RBL2/E2F4 blocks transcription of the proapoptotic genes including E2F1, Apaf-1, and p73α.42 Conversely, an E2F4-deficient heart exhibits elevated levels of E2F1, Apaf-1, and p73α, resulting in increased cardiomyocyte apoptosis and impaired systolic function.42 Therefore, the loss of Rbl2 may inhibit the function of E2F4, resulting in increased proapoptotic gene expression after the DOX challenge. In addition, the RB proteins are primarily known for inducing cell-cycle arrest.17 Rb1 and Rbl2 are the predominant RB proteins expressed in the adult heart.18,19 Although the deletion of either Rb1 or Rbl2 alone does not produce an apparent phenotype, combined ablation of Rb1 and Rbl2 results in a 3-fold increase in heart weight caused by cardiomyocyte S- and M-phase cell-cycle re-entry.18 Because DOX preferentially kills cells in active growing phases,43 it is possible that the loss of Rbl2 increases sensitivity to DOX through invoking cardiomyocyte cell cycle re-entry.

Our results suggest that Rbl2 deficiency upregulates the proapoptotic Bcl2 family member Bim. It is well established that Bim directly activates Bax to cause mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, resulting in caspase-dependent apoptotic cell death.44 Intriguingly, Bax is also necessary for caspase-independent necrotic cell death, which is driven by opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore.45,46 A small-molecule Bax inhibitor protects against DOX cardiotoxicity via blockade of both apoptosis and necrosis.47 DOX can also induce necrosis by activation of Bnip3.48,49 Interestingly, our most recent findings revealed that Bnip3 expression after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion is augmented by Rbl2 ablation.27 In the current study, we showed that the depletion of Rbl2 exacerbates DOX-induced loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, which is often caused by mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening. Therefore, it is possible that the loss of Rbl2 may also aggravate DOX-induced necrosis.

Study limitations

This study primarily focuses on apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. However, anthracyclines are known to activate various cell death pathways and affect nonmyocyte cells.50 Because the Rbl2−/− mice lack Rbl2 expression in all cell types, we cannot exclude the possibility that Rbl2 may regulate anthracycline cardiotoxicity by modulating other cell death pathways or the nonmyocyte cells. In addition, the role of Rbl2 in cardiac chemosensitivity needs to be validated in a tumor-bearing mouse model. Although the association of RBL2 with anthracycline cardiotoxicity was confirmed in 2 independent patient cohorts, our results are limited by the small case numbers, particularly for the CPNDS cohort. Moreover, the SJLIFE cohort only included patients with European ancestry because the systematic differences in allele frequencies across ancestries can confound genetic association and lead to false positives.51 A separate analysis for African ancestry was not feasible considering the relatively small sample size and the lower frequency of the G allele in this population.

Conclusions

The loss of Rbl2 primes cardiomyocytes for apoptosis by augmenting the CDK2-FOXO1-Bim axis, resulting in increased cardiac chemosensitivity. The rs17800727 G allele of the human RBL2 gene is associated with a lower risk of anthracycline cardiotoxicity. Our findings, if validated by others, may provide a new strategy for the prediction of individual susceptibility to anthracycline cardiotoxicity (Central Illustration).

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: Human RBL2 genetic variations may help identify cancer patients at risk of developing anthracycline cardiotoxicity.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: Future studies are needed to validate the association between RBL2 genetic variants and cardiac chemosensitivity in larger populations of cancer survivors and patients.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health (R00HL119605 and R56HL145034 to Dr Cheng; R01HL151472 to Dr Cheng and Dr Chow); National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (R01CA211996 to Dr Chow); and WSU College of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. The SJLIFE study was supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (CA195547, CA21765, and CA261898). The CPNDS work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr Xia was partially supported by T32HL007208 during manuscript preparation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr Chow has received research funds from Abbott Laboratories for work unrelated to this project. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

Dr Xia is now with the Cardiovascular Research Center, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Kathryn Ruddy, MD, served as the Guest Editor for this paper.

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For an expanded Methods section and supplemental tables and figures, please see the online version of this paper.

Appendix

References

- 1.Miller K.D., Nogueira L., Mariotto A.B., et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:363–385. doi: 10.3322/caac.21565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curigliano G., Cardinale D., Dent S., et al. Cardiotoxicity of anticancer treatments: epidemiology, detection, and management. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:309–325. doi: 10.3322/caac.21341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatia S. Genetics of anthracycline cardiomyopathy in cancer survivors: JACC: CardioOncology state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol CardioOnc. 2020;2:539–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2020.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visscher H., Ross C.J., Rassekh S.R., et al. Pharmacogenomic prediction of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in children. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1422–1428. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.3467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aminkeng F., Bhavsar A.P., Visscher H., et al. A coding variant in RARG confers susceptibility to anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in childhood cancer. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1079–1084. doi: 10.1038/ng.3374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magdy T., Jouni M., Kuo H.H., et al. Identification of drug transporter genomic variants and inhibitors that protect against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Circulation. 2022;145:279–294. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.055801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magdy T., Jiang Z., Jouni M., et al. RARG variant predictive of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity identifies a cardioprotective therapy. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28:2076–2089.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aminkeng F., Ross C.J., Rassekh S.R., et al. Recommendations for genetic testing to reduce the incidence of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82:683–695. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace K.B., Sardao V.A., Oliveira P.J. Mitochondrial determinants of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2020;126:926–941. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.314681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng Z., DiMichele L.A., Rojas M., Vaziri C., Mack C.P., Taylor J.M. Focal adhesion kinase antagonizes doxorubicin cardiotoxicity via p21(Cip1.) J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;67:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xia P., Liu Y., Chen J., Coates S., Liu D.X., Cheng Z. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis and cardiomyopathy. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:19672–19685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xia P., Chen J., Liu Y., Fletcher M., Jensen B.C., Cheng Z. Doxorubicin induces cardiomyocyte apoptosis and atrophy through cyclin-dependent kinase 2-mediated activation of forkhead box O1. J Biol Chem. 2020;295:4265–4276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.011571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xia P., Liu Y., Chen J., Cheng Z. Cell cycle proteins as key regulators of postmitotic cell death. Yale J Biol Med. 2019;92:641–650. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varjosalo M., Keskitalo S., Van Drogen A., et al. The protein interaction landscape of the human CMGC kinase group. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1306–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Luca A., MacLachlan T.K., Bagella L., et al. A unique domain of pRb2/p130 acts as an inhibitor of Cdk2 kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20971–20974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.20971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woo M.S., Sanchez I., Dynlacht B.D. p130 and p107 use a conserved domain to inhibit cellular cyclin-dependent kinase activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3566–3579. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Indovina P., Marcelli E., Casini N., Rizzo V., Giordano A. Emerging roles of RB family: new defense mechanisms against tumor progression. J Cell Physiol. 2013;228:525–535. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacLellan W.R., Garcia A., Oh H., et al. Overlapping roles of pocket proteins in the myocardium are unmasked by germ line deletion of p130 plus heart-specific deletion of Rb. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2486–2497. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2486-2497.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sdek P., Zhao P., Wang Y., et al. Rb and p130 control cell cycle gene silencing to maintain the postmitotic phenotype in cardiac myocytes. J Cell Biol. 2011;194:407–423. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201012049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hatzistergos K.E., Williams A.R., Dykxhoorn D., Bellio M.A., Yu W., Hare J.M. Tumor suppressors RB1 and CDKN2a cooperatively regulate cell-cycle progression and differentiation during cardiomyocyte development and repair. Circ Res. 2019;124:1184–1197. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alam P., Haile B., Arif M., et al. Inhibition of senescence-associated genes Rb1 and Meis2 in adult cardiomyocytes results in cell cycle reentry and cardiac repair post-myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liem D.A., Zhao P., Angelis E., et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 signaling regulates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45:610–616. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.George J., Lim J.S., Jang S.J., et al. Comprehensive genomic profiles of small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2015;524:47–53. doi: 10.1038/nature14664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savage J.E., Jansen P.R., Stringer S., et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis in 269,867 individuals identifies new genetic and functional links to intelligence. Nat Genet. 2018;50:912–919. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0152-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee J.J., Wedow R., Okbay A., et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1112–1121. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0147-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunet T., Radivojkov-Blagojevic M., Lichtner P., Kraus V., Meitinger T., Wagner M. Biallelic loss-of-function variants in RBL2 in siblings with a neurodevelopmental disorder. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020;7:390–396. doi: 10.1002/acn3.50992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J., Xia P., Liu Y., Kogan C., Cheng Z. Loss of Rbl2 (Retinoblastoma-like 2) exacerbates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(19) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.024764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cobrinik D., Lee M.H., Hannon G., et al. Shared role of the pRB-related p130 and p107 proteins in limb development. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1633–1644. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagashima T., Shigematsu N., Maruki R., et al. Discovery of novel forkhead box O1 inhibitors for treating type 2 diabetes: improvement of fasting glycemia in diabetic db/db mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:961–970. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.065714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sapkota Y., Qin N., Ehrhardt M.J., et al. Genetic variants associated with therapy-related cardiomyopathy among childhood cancer survivors of African ancestry. Cancer Res. 2021;81:2556–2565. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pollard D.A., Pollard T.D., Pollard K.S. Empowering statistical methods for cellular and molecular biologists. Mol Biol Cell. 2019;30:1359–1368. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-02-0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee S., Emond M.J., Bamshad M.J., et al. Optimal unified approach for rare-variant association testing with application to small-sample case-control whole-exome sequencing studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:224–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jordan J.H., Castellino S.M., Melendez G.C., et al. Left ventricular mass change after anthracycline chemotherapy. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11 doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Willis M.S., Parry T.L., Brown D.I., et al. Doxorubicin exposure causes subacute cardiac atrophy dependent on the striated muscle-specific ubiquitin ligase MuRF1. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12 doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.118.005234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen J., Yusuf I., Andersen H.M., Fruman D.A. FOXO transcription factors cooperate with delta EF1 to activate growth suppressive genes in B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2006;176:2711–2721. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang S., Liu X., Bawa-Khalfe T., et al. Identification of the molecular basis of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nat Med. 2012;18:1639–1642. doi: 10.1038/nm.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kruman, Wersto R.P., Cardozo-Pelaez F., et al. Cell cycle activation linked to neuronal cell death initiated by DNA damage. Neuron. 2004;41:549–561. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bourke E., Brown J.A., Takeda S., Hochegger H., Morrison C.G. DNA damage induces Chk1-dependent threonine-160 phosphorylation and activation of Cdk2. Oncogene. 2010;29:616–624. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J., Dai S., Chen X., et al. Mechanism of forkhead transcription factors binding to a novel palindromic DNA site. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:3573–3583. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calissi G., Lam E.W., Link W. Therapeutic strategies targeting FOXO transcription factors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021;20:21–38. doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-0088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bagella L., Sun A., Tonini T., et al. A small molecule based on the pRb2/p130 spacer domain leads to inhibition of cdk2 activity, cell cycle arrest and tumor growth reduction in vivo. Oncogene. 2007;26:1829–1839. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dingar D., Konecny F., Zou J., Sun X., von Harsdorf R. Anti-apoptotic function of the E2F transcription factor 4 (E2F4)/p130, a member of retinoblastoma gene family in cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;53:820–828. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ling Y.H., el-Naggar A.K., Priebe W., Perez-Soler R. Cell cycle-dependent cytotoxicity, G2/M phase arrest, and disruption of p34cdc2/cyclin B1 activity induced by doxorubicin in synchronized P388 cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:832–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chi X., Nguyen D., Pemberton J.M., et al. The carboxyl-terminal sequence of bim enables bax activation and killing of unprimed cells. Elife. 2020;9 doi: 10.7554/eLife.44525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whelan R.S., Konstantinidis K., Wei A.C., et al. Bax regulates primary necrosis through mitochondrial dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:6566–6571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201608109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karch J., Kwong J.Q., Burr A.R., et al. Bax and Bak function as the outer membrane component of the mitochondrial permeability pore in regulating necrotic cell death in mice. Elife. 2013;2 doi: 10.7554/eLife.00772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amgalan D., Garner T.P., Pekson R., et al. A small-molecule allosteric inhibitor of BAX protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Nat Cancer. 2020;1:315–328. doi: 10.1038/s43018-020-0039-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dhingra R., Margulets V., Chowdhury S.R., et al. Bnip3 mediates doxorubicin-induced cardiac myocyte necrosis and mortality through changes in mitochondrial signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E5537–E5544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414665111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dhingra R., Guberman M., Rabinovich-Nikitin I., et al. Impaired NF-kappaB signalling underlies cyclophilin D-mediated mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening in doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:1161–1174. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Antoniak S., Phungphong S., Cheng Z., Jensen B.C. Novel mechanisms of anthracycline-induced cardiovascular toxicity: a focus on thrombosis, cardiac atrophy, and programmed cell death. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.817977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hellwege J.N., Keaton J.M., Giri A., Gao X., Velez Edwards D.R., Edwards T.L. Population stratification in genetic association studies. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2017;95:1.22.1–1.22.23. doi: 10.1002/cphg.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.