Although vaccines against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) are generally well tolerated, since mass vaccination against COVID-19 began, the number of vaccine-linked cases of the de novo or relapsing glomerular diseases has been growing. Most cases have been associated with mRNA and adenovirus vector deliveries vaccines [1–7]. Göndör et al. recently reported a case of relapse of idiopathic immune complex–mediated membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (IC-MPGN) after Pfizer's vaccine [8]. Although mentioned in article by Fenoglio et al. [7], to the best of our knowledge, de novo IC-MPGN triggered by COVID-19 vaccine has not been yet described according to available literature. We report a case of de novo IC-MPGN after the first dose of AstraZeneca vaccine.

Case description: A 65-year-old man with history of arterial hypertension, right-side nephrectomy due to trauma and diabetes mellitus type 2 of 2 months’ duration presented to emergency department on 27 April 2021 with rapid-onset shortness of breath. His chronic medication included metformine, statin, perindopril and amlodipine. He had no previous adverse reactions to vaccines or history of hypersensitivity. On 7 April he received the first dose of AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) of nasopharyngeal swab was negative. He was diagnosed with bilateral segmental pulmonary embolism (PE) and incipient bilateral pulmonary effusion, and admitted to regional hospital. Complete blood cell count was normal, serum creatinine (sCr) was 88 μmol/L, serum albumin was 38 g/L and urine sediment was normal with proteins 1+ on dipstick. Diagnostic workup excluded deep venous thrombosis and there was no evidence of underlying malignant disease. He was treated with dalteparin and a low dose of furosemide, and after 7 days was discharged with rivaroxaban (5 mg twice daily), long-acting insulin, metformine/empagliflozin, statin and perindopril/amlodipine. Four days after hospital discharge (31 days after vaccination), he noticed progressive lower limb swelling and urine foaming and, due to worsening of symptoms and development of severe hypertension (210/110 mmHg), was referred to emergency department on 14 May. Diagnostic workup revealed elevated sCr (159 μmol/L), progression of pleural effusions, proteinuria (dipstick 3+) and erythrocyturia. At that moment, he was respiratory sufficient and not prone to hospitalization. He was recommendation for additional furosemide (40 mg twice daily) and antihypertensive therapy, and was referred to a nephrologist urgently. He visited a private nephrologist on 24 May (laboratory data shown in Table 1). Rivaroxaban was replaced with reduced dose of apixaban (2.5 mg twice daily) and eplerenone (12.5 mg twice daily) was added to the prior therapy. Despite strong recommendation for additional inpatient workup and treatment, he was not prone to hospitalization until 30 September, when he was admitted in our hospital (PCR to SARS-CoV-2 was negative). After kidney ultrasound evaluation, kidney biopsy was performed due to persistent nephrotic-nephritic syndrome with renal insufficiency and refractory hypertension. Table 1 summarizes the relevant patient data. Histopathological analysis showed a membranoproliferative pattern of injury with immunoglobulin G, C3 and C1q deposits on immunofluorescence and characteristic findings on electron microscopy (Fig. 1). Chronic changes were mild and diagnosis of IC-MPGN of unclear etiology was established. The extensive clinical workup including complement system analysis ruled out neoplasia, infections, hematologic and other malignant disorders, as well as complement system dysregulation. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 serology performed 6 months after vaccination was negative. Methylprednisolone (MP) 1 mg/kg therapy was started and after workup completion, he received six doses of cyclophosphamide (500 mg) in a 3-week period. Low dose of MP was continued, and after a follow-up of 15 months, significant reduction of proteinuria was achieved with minimal erythrocyturia and stable renal function (Table 1).

Table 1:

Relevant patient's characteristics over time and treatment response.

| Patient's characteristics (units, ref.) | 24 May 2021 | 30 September 2021 (Bx) | 13 January 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/L, 138–175) | 143 | 122 | 128 |

| Gross hematuria | No | No | No |

| Erythrocyturia (per HPF, <3) | >100 | >100 | 6–10 |

| 24-h proteinuria (g/day, <0.15) | 4+ (dipstick) | 25 | 0.9 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L, 64–104) | 324 | 315 | 220 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2, ≥60) | 16 | 17 | 26 |

| Serum albumin (g/L, 41–51) | 23 | 28 | 45 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L, <5) | n/a | 8.1 | 4.9 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L, 1.7) | n/a | 2.5 | 1.6 |

| C4 (mg/L, 0.1–0.4) | n/a | 0.51 | n/a |

| C3 (mg/L, 0.9–1.8) | n/a | 1.48 | n/a |

Bx, kidney biopsy; n/a, not available; HPF, high-powered field; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

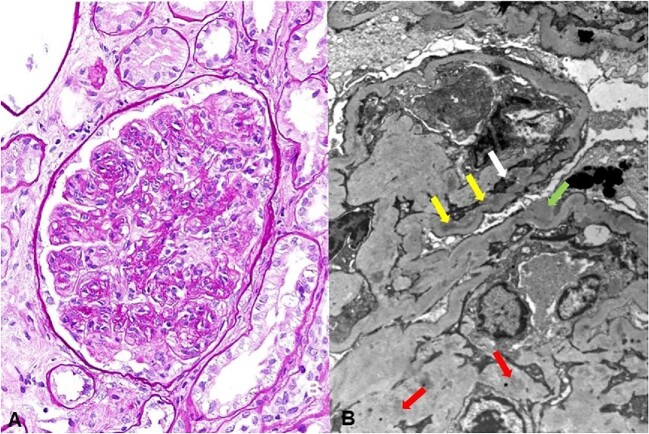

Figure 1:

(A) Membranoproliferative pattern in glomerulus, periodic acid–Schiff stain, original magnification ×400. (B) Remodeling of glomerular basement membrane with mesangial interposition (white arrow) and subendothelial (yellow arrows), subepithelial (green arrow) and mesangial immune deposits (red arrows), transmission electron microscopy, original magnification ×5000.

We reported a case of de novo IC-MPGN in a patient who received AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine 31 days before onset of first symptoms. Extensive diagnostic workup did not reveal any underlying cause of IC-MPGN which supports the possible role of vaccine-induced immune response in the pathogenesis of the disease. Preceding PE could be also linked to AstraZeneca vaccine and early stage of the ongoing nephrotic state could contribute to development of PE [9]. Selected immunosuppressive treatment was very effective in proteinuria reduction and stabilization of kidney function. To the best of our knowledge, there is only one mention of de novo MPGN after a second dose of Moderna vaccine in the literature, but without detailed description [7]. Sethi et al. reported a case of IC-MPGN after COVID-19 infection in a patient with previously known focal segmental glomerulosclerosis [10]. There is a report of MPGN in animal medicine after probable over-vaccination in dog [11]. Although the temporal association between vaccination and onset of first nephrologic symptoms in our case is consistent with previously reported cases of COVID-19 vaccine-linked nephrologic conditions, causality between vaccine and MPGN can only be presumed, so further investigations are needed to clarify this relationship.

Contributor Information

Nikola Zagorec, Department of Nephrology and Dialysis, Dubrava University Hospital, Zagreb, Croatia.

Martin Bojić, School of Medicine, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia.

Dino Kasumović, Department of Nephrology and Dialysis, Dubrava University Hospital, Zagreb, Croatia.

Petar Šenjug, School of Medicine, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia; Department of Pathology and Cytology, Dubrava University Hospital, Zagreb, Croatia.

Danica Galešić Ljubanović, School of Medicine, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia; Department of Pathology and Cytology, Dubrava University Hospital, Zagreb, Croatia.

Krešimir Galešić, Department of Nephrology and Dialysis, Dubrava University Hospital, Zagreb, Croatia; School of Medicine, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia.

Ivica Horvatić, Department of Nephrology and Dialysis, Dubrava University Hospital, Zagreb, Croatia; School of Medicine, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia.

FUNDING

No funding was received for this work.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, N.Z., M.B and I.H.; methodology, N.Z., P.Š. and D.G.L.; validation, K.G., D.G.L. and I.H.; investigation, N.Z., M.B. and D.K.; data curation, D.K., M.B. and P.Š.; writing—original draft preparation, N.Z. and I.H.; writing—review and editing, D.K., P.Š., D.G.L., K.G. and I.H.; visualization, P.Š. and D.G.L.; supervision, D.G.L., K.G. and I.H.; all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Klomjit N, Priya AM, Fervenza FC.et al. COVID 19 vaccination and glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int Rep 2021;6:2969–78. 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bomback AS, Kudose S, D'Agati VD. De novo and relapsing glomerular diseases after COVID-19 vaccination: what do we know so far? Am J Kidney Dis 2021;78:477–80. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tan HZ, Tan RY, Choo J.et al. Is COVID-19 vaccination unmasking glomerulonephritis? Kidney Int 2021;100:469–71. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morlidge C, El-Kateb S, Jeevaratnam P.et al. Relapse of minimal change disease following the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Kidney Int 2021;100:459. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gillion V, Jadoul M, Demoulin N.et al. Granulomatous vasculitis after the AstraZeneca anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Kidney Int 2021;100:706–7. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Villa M, Diaz-Crespo F, Perez de Jose A.et al. A case of ANCA-associated vasculitis after AZD1222 (Oxford–AstraZeneca) SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: casualty or causality? Kidney Int 2021;100:937–8. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fenoglio R, Lalloni S, Marchisio M.et al. New onset biopsy-proven nephropathies after COVID vaccination. Am J Nephrol 2022;53:325–30. 10.1159/000523962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Göndör G, Ksiazek SH, Regele Het al. Development of crescentic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis after COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Kidney J 2022;15:2340–2. 10.1093/ckj/sfac222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dag Berild J, Bergstad Larsen V, Myrup Thiesson E.et al. Analysis of thromboembolic and thrombocytopenic events after the AZD1222, BNT162b2, and MRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccines in 3 Nordic countries. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e2217375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sethi S, D'Costa MR, Hermann SMet al. Immune-complex glomerulonephritis after COVID-19 infection. Kidney Int Rep 2021;6:1170–3. 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ortloff A, Morán G, Olavarría A.et al. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis possibly associated with over-vaccination in a cocker spaniel. J Small Anim Pract 2010;51:499–502. 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2010.00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]