Highlights

-

•

Ultrasonic treatment changed protein solubility and surface hydrophobicity.

-

•

Ultrasonic treatment enhanced protein emulsification.

-

•

Ultrasonic treatment increased the α-helix, random coil, and hydrophobic amino acid content.

-

•

Ultrasonic treatment improved digestibility of seed protein.

-

•

Cactus seed protein remodeled intestinal homeostasis.

Keywords: Cactus fruits, Protein, Byproduct, Chemical structure, Digestibility

Abstract

With the steady increase in the consumption of ultra-processed foods, there is growing interest in sustainable diets that include more plant protein. However, little information is available regarding the structural and functional properties of cactus (Opuntia ficus-indica) seed protein (CSP), a by-product of the cactus seed food-processing chain. This study aimed to explore the composition and nutritional value of CSP and reveal the effects of ultrasound treatment on protein quality. Protein chemical structure analysis showed that an appropriate intensity of ultrasound treatment (450 W) could significantly increase protein solubility (96.46 ± 2.07%) and surface hydrophobicity (13.76 ± 0.85 μg), decrease the content of T-SH (50.25 ± 0.79 μmol/g) and free-SH (8.60 ± 0.30 μmol/g), and enhance emulsification characteristics. Circular dichroism analysis further confirmed that the ultrasonic treatment increased the α-helix and random coil content. Amino acid analysis also suggested that ultrasound treatment (450 W) increased the hydrophobic amino acid content. To evaluate the impact of changes in the chemical structure, its digestion behavior was studied. The results showed that ultrasound treatment increased the release rate of free amino acids. Furthermore, nutritional analysis showed that the digestive products of CSP by ultrasound treatment can significantly enhance the intestinal permeability, increase the expression of ZO-1, Occludin and Claudin-1, thus repairing LPS induced intestinal barrier disfunction. Hence, CSP is a functional protein with high value, and ultrasound treatment is recommended. These findings provide new insights into the comprehensive utilization of cactus fruits.

1. Introduction

Previous studies have shown that cactus fruits have a high nutritional and economic value. The roots and stems of cactus fruits can lower blood lipid, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels and have anti-inflammatory properties [1], [2]. Moussa Ayoub et al. found that cactus fruits contain large amounts of phenolic compounds [1]. Stintzing et al. determined that cactus peel is rich in a large amount of stable water-soluble pigments [3], [4]. However, cactus fruits contain numerous underutilized fruit seeds, leading to a waste of resources. Our previous study found that cactus fruit seeds are rich in proteins; however, their nutritional value and functional characteristics are currently unknown.

Compared with animal proteins, plant proteins have attracted attention because of their sustainable sources, economic costs, and health benefits, and they are widely used as emulsifiers, gelling agents, and fat substitutes in food [5]. However, because of the complexity of plant cell walls and the presence of various anti-nutritional factors, their water solubility is poor, and they are sensitive to environmental conditions, such as pH, salt, and temperature, which limits the practical application and production of plant proteins [6]. Therefore, it is important to develop green and efficient plant protein modification methods to improve their functional characteristics, meet different functional and nutritional requirements, and expand their applications in the food industry.

As a natural, green, pollution-free, simple, and convenient processing technology, utilizing the physical effects of ultrasound to change the chemical structure of proteins is currently a widely used protein modification method. This method can change the secondary structure of proteins, is relatively safe, and has a lower cost than other modification methods. The modification effect is substantial, environmentally friendly, and nontoxic, and the loss percentage of product nutrients is relatively low. Ultrasound-induced protein modifications are usually attributed to the cavitation effect of ultrasound. The energy generated by the ultrasound can be transmitted to a fluid medium, rapidly generating high-pressure regions and rapidly growing small cavities. When a cavity expands and ruptures, transient high temperatures (5000 K), high pressures (1000 atm), high-energy shear waves, and turbulence are generated in the cavitation area [7], [8]. Cavitation can alter protein structure by disrupting hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions between protein molecules. This modification can significantly improve the solubility, gelling, emulsification, and foaming properties of proteins, help reduce the size of protein aggregates, and change the molecular structure of proteins [9]. Many studies have shown that, owing to the partial unfolding of plant-based proteins and surface exposure of buried sulfhydryl (SH) groups, the content of free thiol groups increases after ultrasonic treatment. In addition, because of cavitation, disulfide bonds (S-S) are reduced, allowing the formation of more SH groups, and indicating partial unfolding of proteins and reduced intermolecular interactions [10]. However, the effect of ultrasound modification on the chemical structure of cactus seed protein (CSP) remains unknown.

As a direct method of protein modification, ultrasound can change protein structure by destroying chemical bonds within the protein, thus affecting its functional properties. Xiong et al. found that ultrasonic modification of a pea protein isolate significantly improved its foaming ability [9]. Dabbour et al. found that, compared to enzymatic modification, ultrasonic modification significantly improved the solubility, foaming ability, emulsification performance, and antioxidant capacity of sunflower protein [11]. However, the impact of ultrasound modification on the functional characteristics of CSP is unknown.

This study is based on the advantages of ultrasonic modification, such as high energy effectiveness, low cost, easy operation, environmental friendliness, and exceptional safety, and uses ultrasonic modification to treat CSP. The effects of different ultrasonic power levels on protein solubility, surface hydrophobicity, free sulfhydryl (free-SH) content, and secondary structure were studied. To evaluate the nutritional quality, LPS induced inflammatory intestinal barrier model was applied. All these efforts aim to provide a source of high-quality protein and efficient comprehensive utilization of cactus byproducts.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Cactus fruit, a green peeled and red fleshed variety, was picked in May and June 2021 from Sanya, Hainan Province, China. The cuticle of the fruit was cleaned and the peel, pulp, and fruit were separated prior to testing. Caco-2 cells were obtained from the National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (Shanghai, China). All chemicals were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Preparation of CSP

Separate the cactus seed from the flesh, wash and dry it, grind it into powder, pass it through a 100-mesh sieve, and extract the crude fat using the Soxhlet extraction method. Repeat the extraction process until the crude fat content does not exceed 0.5%. Dry the obtained cactus seed meal and seal it in a sample bag for later use.

Weigh an appropriate amount of cactus seed meal, add distilled water in a material to liquid ratio of 1:20, adjust the pH to 11 using 1 mol/L NaOH solution, place in a 40 ℃ water bath for 40 min, centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 10 min, and adjust the pH of the supernatant using 1 mol/L HCl to 3.0, 3.5, 4.0, 4.5, 5.0, 5.5, and 6.0. Let it stand and then centrifuge, discard the supernatant, freeze dry, and weigh the resultant mass. The pH at the maximum precipitation is the isoelectric point of the CSP.

The alkaline extraction and acid precipitation method is used to extract proteins from cactus fruit seeds. The detailed steps are as follows: Mix cactus seed meal with ultrapure water (1:20, g/g), adjust the pH to 11 using 1 mol/L NaOH solution, and extract for 30 min at 40 ℃. Subsequently, centrifuge the supernatant at 8000 rpm for 10 min. Adjust the pH of the obtained supernatant to the isoelectric point of the protein using 1 mol/L HCl solution. Allow it to settle at room temperature for 2 h, and then centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 10 min. Discard the supernatant and wash the precipitate with deionized water to a pH of 7.0. Dialyze the precipitate for 48 h to remove salt, and finally freeze-dry (80 ℃, 1.3 MPa, 24 h) to obtain the CSP.

2.3. Preparation of protein by ultrasonic treatment

Dissolve an appropriate amount of CSP in distilled water and stir at 25 ℃ for 2 h until completely hydrated. Then, subject the sample to ultrasonic treatment in an ultrasound processor equipped with a 2.0 cm flat tip probe. Treat the samples using different powers (150 W, 300 W, 450 W, and 600 W). The opening and closing time of the ultrasound is 10 s. During processing, subject the sample to an ice water bath to maintain a temperature of 25 ± 2 °C. Freeze dry the protein solution after ultrasonic treatment and store at 4 °C. Use untreated CSP as the control sample.

2.4. Protein chemical structure analysis

Solubility was determined using the Bradford method, as previously described [12]. Surface hydrophobicity was determined using the bromophenol blue method as previously described [13]. The total (T) and free SH contents were determined according to the method described by Beveridge et al. [14].

2.5. Amino acid analysis

Amino acids were determined using a HITACHI RD001931 automatic amino acid analyzer. Briefly, the analysis required a 50 mg sample, which was treated with 10 mL of 6 mol/L HCl to protect the nitrogen atoms, before it was subjected to hydrolysis at 110 °C for 22 h; the amino acid content was then determined after performic acid oxidation except for tryptophan. Tryptophan content was determined calorimetrically after alkaline hydrolysis [15].

2.6. Fat absorption capacity (FAC) and water absorption capacity (WAC) analysis

Briefly, FAC and WAC were determined as followed. Samples (100 mg) and deionized water/oil (1000 μL) were taken in a centrifuge tube. The slurry was mixed for 10 s using a vortex mixer, and the mixed sample was allowed to settle for 30 min. The suspension was centrifuged at 8000 g for 10 min (temperature at 25 °C). The supernatant was decanted off and the contents of the tube were drained over a period of 20 min (angle: 45◦). The weight difference recorded before and after drainage was divided by the weight of the dry sample to determine the FAC and WAC values.

2.7. Mean particle diameter and surface potential analysis

The mean particle diameter and surface potential (zeta-potential) of the samples were measured at 25 °C using a static light scattering laser particle size analyzer (Zetasizer nano ZS). Before measurement, the sample was diluted to the appropriate shading range to avoid multiple light-scattering effects [16].

2.8. Determination of emulsifying properties

The emulsifying properties were measured as described previously [17]. Briefly, 0.1% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate was diluted 100-fold and added to 50 μL of fresh emulsion. The absorbance of the diluted emulsion was measured at 500 nm using a spectrophotometer. The emulsion activity index (EAI) and emulsion stability index (ESI) were calculated as follows:

where A0 is the absorbance at 0 min, DF is the dilution factor (1 0 0), C is the protein concentration (g/mL) before emulsification, θ is the oil volume fraction (v/v) of the emulsion, L is the optical path (1 cm), and A10 is the absorbance at 10 min.

2.9. Gastrointestinal digestion analysis

The pH-stat method was used for in vitro gastrointestinal digestion according to previous studies [18]. The OPA method was used to determine the release of free amino acids (AAs) from enzymatic hydrolysates obtained through in vitro-simulated gastrointestinal digestion [19]. Each sample was centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 20 min and the supernatant was ultra-filtered. Components with molecular weights of <3 kDa were collected by centrifugation at 15000 rpm for 20 min.

2.10. Cell culture and treatment

Caco-2 cells were subjected to cultivation in MEM medium encompassing 1% glutamax, 1%, non-essential amino acids, 1% sodium pyruvate 100 mM Solution (all from Gibco, U.S.A.), and 20% FBS (Hyclone, U.S.A.). These cells were cultivated under the conditions of 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37 °C.

Caco-2 cells were subjected to 21-day cultivation in transwell insert plates (1.5 × 105 cells/cm2; available from Corning, Cambridge, MA, USA), and a targeted cell monolayer with a transepithelial electrical resistance value (TEER) was acquired with a Millicell ERS-2 V-ohm meter (available from Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA) [20].

Caco-2 cells were subjected to 12-h treatment with LPS (10 μg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) to establish intestinal barrier damage model. Subsequently, Caco-2 cells were treated for 24 h with digestive products of CSP (CSP-DP) (20 μM) in intestinal barrier damage model to validate the nutritional quality.

2.11. Measurement of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and malonic dialdehyde (MDA)

Using the reactive Oxygen Species Assay Kit (Beyotime), the ROS levels was appraised by evaluating the changes in 20,70-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) fluorescence. Lipid Peroxidation MDA Assay Kit (Beyotime) was adopted for assessing the MDA levels.

2.12. qPCR analysis

qPCR analysis was implemented for testing the relative mRNA expression in Caco-2 cells. In detail, Caco-2 cells were estimated with drugs (LPS, GT, and EGT), and then the extraction of the total RNAs from Caco-2 cells was achieved with FastPure Cell/Tissue Total RNA Isolation Kit V2 (Vazyme). After that, the reverse transcription of the total RNAs into cDNA was achieved with the HiScript III RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) (Vazyme). qPCR was executed with a SGExcel FastSYBR Green qPCR Master Mix kit (Vazyme). Then, the primer sequences in Table 1 were utilized for the relative mRNA expression, which was counted by means of the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for quantitative real-time RNA.

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| Claudin-1 | 5′-GCTGTGGATGTCCTGCGTGTC-3′ | 5′-ACCTCATCGTCTTCCAAGCACTTC-3′ |

| Zo-1 | 5′-AGGAGGTAGAACGAGGCATCATCC-3′ | 5′-TCTCCAGAAGTCAGCACGGTCTC-3′ |

| Occludin | 5′- AACTTCGCCTGTGGATGACTTCAG-3′ | 5′- GACTCGCCGCCAGTTGTGTAG-3′ |

2.13. Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed at least three times, and the results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The experimental data were plotted using Origin 2019 and analyzed for significance using SPSS 18.0. A one-way ANOVA (Tukey's test) was used to test for statistically significant differences. P < 0.05 was set as a significant difference.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effect of ultrasonic extraction on solubility

Protein solubility is considered the most practical indicator for measuring the functional properties of proteins and is closely related to the functional properties of emulsification and foaming. An increase in protein solubility can improve the emulsifying properties of proteins. Therefore, good solubility is a prerequisite for the use of proteins as emulsifiers. Fig. 1 showed changes in protein solubility after ultrasound treatment. The solubility of the protein was 80.41 ± 2.61%, and, after ultrasound treatment, the solubility of the protein significantly increased. This may be due to the direct effect of ultrasound treatment on proteins, which instantly generates high pressure, causing shear, cavitation, turbulence, surface electrostatic, and thermodynamic effects, leading to protein denaturation, structural opening, and the generation of additional negative charges on the protein surface, promoting hydration [21]. As the ultrasound intensity increased, the protein solubility showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. This is because the cavitation effect and shear force generated by the ultrasound can depolymerize protein aggregates, thereby improving their solubility. However, excessive ultrasound treatment can induce the irregular movement of proteins and formation of large aggregates, and increase collision probability, leading to a decrease in protein solubility [22].

Fig. 1.

The effect of ultrasonic extraction on solubility.

3.2. Effect of ultrasonic extraction on surface hydrophobicity

The surface hydrophobicity of proteins can be expressed as the content of hydrophobic amino acid residues formed after exposure to protein side chains. The generation of hydrophobic groups can promote the adsorption of proteins on the surface of oil droplets and prevent protein aggregation and flocculation, and, therefore, has a close relationship with the emulsification characteristics of proteins [23]. As shown in Fig. 2, compared to the control group, the low power did not completely break the three-dimensional structure of the protein, and most of the surface hydrophobic amino acid residues constituting the protein were still located in the molecular structure. As the ultrasound power increased, it accelerated molecular motion and promoted the transfer of hydrophobic amino acid residues embedded within the molecule to the surface of the protein molecule, thereby increasing protein surface hydrophobicity [24].

Fig. 2.

The effect of ultrasonic extraction on surface hydrophobicity.

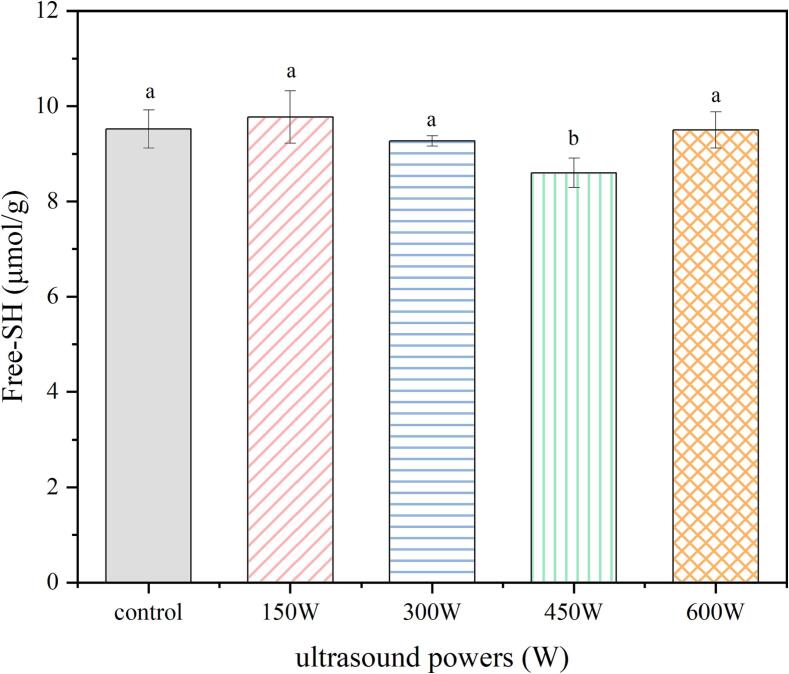

3.3. Effect of ultrasonic extraction on T-SH and free-SH

The disulfide bond is a covalent bond formed by dehydrogenation of the SH groups of two cysteine residues in protein molecules. Its bond energy is relatively high compared to that of other forces that maintain the high-level structure of proteins, such as electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding, and its action distance is relatively small [25]. It is an important chemical bond that stabilizes the protein structure. Fig. 3 showed that, with an increase in ultrasonic power, the T-SH content significantly decreased (p < 0.05), which may be related to the formation of disulfide bonds. Ultrasonic treatment leads to the decomposition of water molecules to form free radicals, which further decompose into hydrogen peroxide and oxidize thiol groups to disulfide bonds, resulting in a decrease in T-SH content [26].

Fig. 3.

The effect of ultrasonic extraction on T-SH.

Free-SH is one of the most important active groups in protein molecules, and its exchange reaction with disulfide bonds can strengthen the interaction between protein molecules and promote the irreversible adsorption of proteins at the oil–water interface, thereby providing a highly viscoelastic membrane to resist protein aggregation. Therefore, the free-SH content can significantly affect the functional characteristics of proteins. As shown in Fig. 4, compared to the seed protein, there was no significant difference in the content of free hydrophobic groups when the ultrasound intensity was 150–300 W. However, it is worth noting that when the ultrasound intensity was 450 W, the free-SH content significantly decreased. The energy generated by ultrasonic cavitation can dissociate water molecules into hydrogen atoms and highly active hydroxyl radicals. The presence of hydroxyl radicals exposes the free-SH groups of protein molecules and oxidizes them into disulfide bonds with a more stable structure [27]. Therefore, the reduction in free-SH group content is a common result of the expansion of the protein molecular space structure promoted by ultrasound and the oxidation of hydroxyl radicals.

Fig. 4.

The effect of ultrasonic extraction on free-SH.

3.4. Effect of ultrasonic extraction on protein secondary structure

Circular dichroism was used to study the effect of ultrasound on the secondary structure of the proteins, and the results were shown in Table 2. Compared with the control group, a continuous increase in ultrasound power (150 W–600 W) reduced the relative contents of α-helix and random coil to 15.13 ± 0.21% and 30.58 ± 0.13%, respectively, and increased the relative contents of β-sheet and β-turn to 29.51 ± 0.09% and 25.02 ± 0.11%, respectively. This may be due to the cavitation effect and mechanical stress generated by the ultrasound, which disrupts the regular arrangement of the α-helix structure, exposing more hydrogen bonds in the unfolded structure of the polypeptide chains to be rearranged by hydrophobic interactions and then reconnected to form the β-structure during the molecular aggregation process [28]. The hydrogen bond between the carbonyl and amino groups in the peptide chain is crucial for maintaining the stability of the helix, and both electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bond stability can affect the helix content. The α-helix conformation is mainly stabilized by intramolecular hydrogen bonds. The decrease in the content of α-helix and random coil means that the intramolecular hydrogen bonds broke, the disordered structure of the protein was reduced, and flexibility was enhanced, which improve the functional characteristics of the protein [29].

Table 2.

Changes in secondary structure of CSP under ultrasonic treatment conditions.

| control | 150 W | 300 W | 450 W | 600 W | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Helix | 22.33 ± 0.11d | 20.71 ± 0.09c | 16.64 ± 0.21b | 14.89 ± 0.16a | 15.13 ± 0.21a |

| β-Sheet | 24.91 ± 0.13a | 25.35 ± 0.15a | 28.03 ± 0.10b | 29.51 ± 0.14c | 29.51 ± 0.09d |

| β-Turn | 18.38 ± 0.09a | 21.27 ± 0.21b | 24.11 ± 0.12c | 25.02 ± 0.10d | 25.02 ± 0.11e |

| Random coil | 34.38 ± 0.12d | 32.67 ± 0.23c | 31.22 ± 0.08b | 30.48 ± 0.11a | 30.58 ± 0.13a |

3.5. Effect of ultrasonic extraction on amino acid composition

AAs are the fundamental units that make up protein molecules. As shown in Table 3, the main AAs in CSP were L-arginine (19.97 ± 0.47) and glutamic acid (14.17 ± 0.41). As the ultrasound power increased, the AA content significantly increased (p < 0.05), indicating that the cavitation effect and mechanical force of the ultrasound exposed AAs buried inside protein molecules through the decomposition of protein aggregates or protein unfolding. Compared to CSP without ultrasound treatment, the content of hydrophobic AAs after ultrasound treatment increased, further indicating that ultrasound treatment can modify protein configuration.

Table 3.

Changes in amino acid composition under ultrasonic treatment conditions.

| Amino acid (Aa) | control | 150 W | 300 W | 450 W | 600 W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL-Methionine (Met) | 0.40 ± 0.10a | 0.42 ± 0.09a | 0.45 ± 0.12a | 0.48 ± 0.01a | 0.51 ± 0.00a |

| L(+)-Cysteine (Cys) | 2.25 ± 0.09c | 2.30 ± 0.12c | 2.01 ± 0.11c | 2.01 ± 0.10c | 1.96 ± 0.12c |

| L-Phenylalanine (Phe) | 4.37 ± 0.13e | 4.36 ± 0.12e | 4.40 ± 0.09e | 4.42 ± 0.11e | 4.43 ± 0.11e |

| Tyrosine (Tyr) | 4.01 ± 0.21e | 4.03 ± 0.09e | 4.08 ± 0.13e | 4.11 ± 0.09e | 4.13 ± 0.10e |

| Lysine (Lys) | 3.61 ± 0.14d | 3.61 ± 0.11d | 3.52 ± 0.12d | 3.53 ± 0.11d | 3.55 ± 0.13d |

| Leucine (Leu) | 4.99 ± 0.21f | 5.02 ± 0.17f | 5.11 ± 0.16f | 5.20 ± 0.17f | 5.22 ± 0.18f |

| L-Threonine (Thr) | 3.59 ± 0.11d | 3.62 ± 0.21d | 3.50 ± 0.14d | 3.48 ± 0.12d | 3.41 ± 0.11d |

| Valine (Val) | 4.17 ± 0.14e | 4.20 ± 0.22e | 4.20 ± 0.14e | 4.23 ± 0.13e | 4.26 ± 0.09e |

| Isoleucine (Ile) | 3.62 ± 0.17d | 3.60 ± 0.18d | 3.68 ± 0.09d | 3.74 ± 0.14d | 3.75 ± 0.10d |

| Tryptophan (Try) | 1.07 ± 0.10b | 1.08 ± 0.09b | 1.07 ± 0.05b | 1.08 ± 0.08b | 1.06 ± 0.00b |

| Histidine (His) | 3.27 ± 0.10d | 3.30 ± 0.17d | 3.29 ± 0.13d | 3.27 ± 0.12d | 3.21 ± 0.04d |

| L-Arginine (Arg) | 19.97 ± 0.47i | 19.95 ± 0.35 h | 19.9 ± 0.33 h | 19.85 ± 0.31 h | 19.81 ± 0.36 h |

| L-Aspartic Acid (Asp) | 5.76 ± 0.25 g | 5.79 ± 0.21f | 5.76 ± 0.29f | 5.77 ± 0.18f | 5.72 ± 0.11f |

| L-Serine (Ser) | 4.19 ± 0.20e | 4.32 ± 0.19e | 4.00 ± 0.18e | 4.00 ± 0.20e | 4.01 ± 0.17e |

| Glutamic acid (Glu) | 14.17 ± 0.41 h | 14.00 ± 0.43 g | 13.87 ± 0.32 g | 13.84 ± 0.27 g | 13.81 ± 0.21 g |

| Glycine (Gly) | 5.45 ± 0.18 g | 5.30 ± 0.22f | 5.29 ± 0.19f | 5.27 ± 0.29f | 5.25 ± 0.19f |

| Alanine (Ala) | 4.08 ± 0.15e | 4.12 ± 0.31e | 4.32 ± 0.21e | 4.40 ± 0.16e | 4.40 ± 0.11e |

| Total Essential Aa | 24.75 ± 0.29j | 24.83 ± 0.31i | 24.86 ± 0.34i | 25.10 ± 0.37i | 25.13 ± 0.23i |

| Total Hydrophobic Aa | 25.64 ± 0.31 k | 25.75 ± 0.38j | 26.24 ± 0.37j | 26.60 ± 0.34j | 26.70 ± 0.27j |

3.6. Effect of ultrasound extraction on functional properties

Compared to the control group, the increase in ultrasound intensity (0 W–600 W) significantly increased the EAI (20.32 ± 1.10 m2/g to 41.58 ± 1.19 m2/g) and ESI (30.35 ± 5.21 min to 67.70 ± 3.01 min) of the protein, indicating that ultrasound treatment not only reduces particle size but also increases molecular fluidity, thereby enhancing the emulsifying ability of the protein (Table 4). In addition, ultrasound treatment significantly improved the FAC and WAC of CSP, which may be influenced by improved molecular flexibility and surface hydrophobicity. The decrease in α-helix content (Table 2) may lead to the stretching of protein molecules, which helps achieve better absorption at the water–oil interface, further confirming this conclusion [30].

Table 4.

Changes of functional properties of CSP under ultrasonic treatment conditions.

| FAC (g/g) | WAC (g/g) | EAI (m2/g) | ESI (min) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| control | 3.80 ± 0.01a | 1.28 ± 0.13a | 20.32 ± 1.10a | 30.35 ± 5.21a |

| 150 W | 4.41 ± 0.03b | 1.79 ± 0.10b | 26.37 ± 2.31b | 41.03 ± 4.10b |

| 300 W | 4.93 ± 0.00c | 2.03 ± 0.17c | 33.15 ± 1.05c | 49.11 ± 3.03c |

| 450 W | 5.26 ± 0.05d | 2.11 ± 0.09c | 38.62 ± 1.31d | 60.56 ± 2.54d |

| 600 W | 5.68 ± 0.07e | 2.19 ± 0.12c | 41.58 ± 1.19e | 67.70 ± 3.01e |

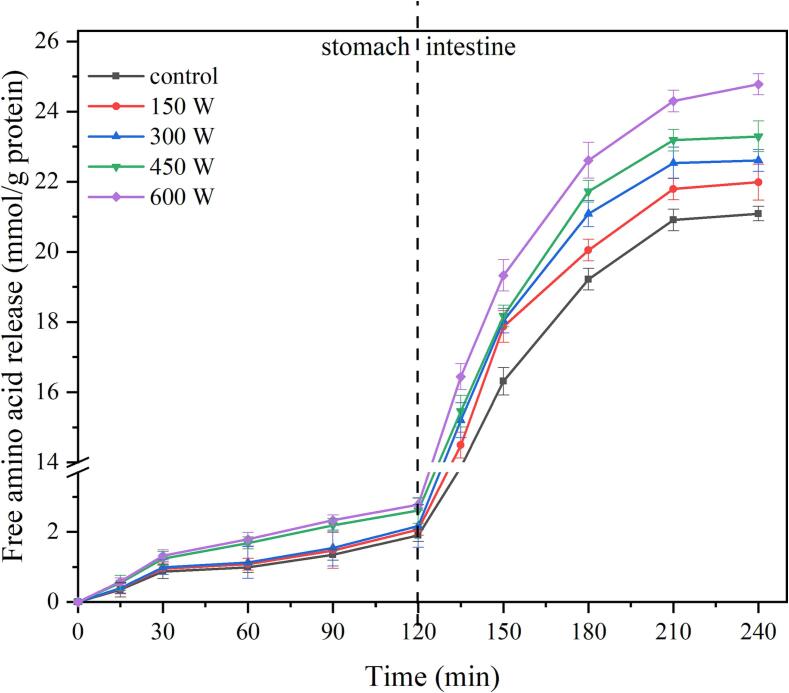

3.7. Effect of ultrasound extraction on digestive behavior

In this study, protein digestibility was represented by free AAs. The content of free AAs of <3 kDa in the enzymatic hydrolysis supernatant of the samples at different digestion stages was measured, and the results were shown in Fig. 5. During the gastric digestion stage, the hydrolysis of pepsin to protein was limited, and the release of free AAs in all samples showed a gentle increasing trend. The amount of free AA released at the end point of gastric digestion was approximately 1.91–2.56 mmol/g protein. When the ultrasound intensity was <300 W, there was no significant difference in the amount of free AAs released. However, as the ultrasound intensity increased, the release of free AAs slightly increased, but there was no significant difference between the ultrasound intensities of 450 W and 600 W. During the intestinal digestion stage, the free AA content significantly increased with the addition of bile and trypsin. At the end point of intestinal digestion, the trend of free AA release in the sample was:600 W treatment (24.78 ± 0.39 mmol/g protein) > 450 W treatment (23.29 ± 0.44 mmol/g protein) > 300 W treatment (22.60 ± 0.31 mmol/g protein) > 150 W treatment (21.99 ± 0.46 mmol/g protein) > control (21.01 ± 0.21 mmol/g protein), and the difference was significant (p < 0.05). Protein digestibility is related to the spatial structure formed during the ultrasonic treatment process. The β-sheet is one of the main components of the secondary structure of proteins. As a rigid structure, it contains numerous hydrogen bonds that hinder the enzymatic hydrolysis of proteins by proteases, which is the main factor affecting the digestion rate. Carbonaro et al. found that the digestibility of food proteins is inversely proportional to the β-sheet content, which is related to the formation of regular and tight polymers during processing [31]. As shown in Table 2, ultrasound treatment increased the β-sheet content, which may explain why the intensity of ultrasound treatment is proportional to the rate of protein digestion. Some studies have shown that intermolecular and intramolecular disulfide bonds determine the degree of protein digestion by trypsin and that proteins that break disulfide bonds have higher digestibility [32]. Therefore, the disulfide bond content in proteins is related to their digestion behavior. This study confirmed that ultrasound treatment can change the protein disulfide bond content, which also explains the difference in the sample digestion rate.

Fig. 5.

The effect of ultrasonic extraction on free amino acid release.

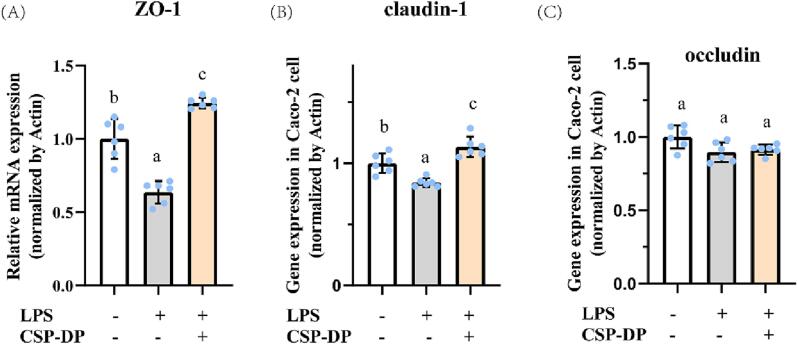

3.8. Effects of CSP on the intestinal homeostasis

Fig. 6(A and B) signified that TEER values of Caco-2 cells in model stimulated with LPS (p < 0.05) significantly decreased (from 315.01 ± 9.19 to 244.12 ± 10.33 Ω·cm2), and CSP-DP significantly increased gut permeability (288.73 ± 8.45 Ω·cm2). Meanwhile, the changes of TEER values were consistent with the expression results of gut barrier permeability related genes including ZO-1, Claudin-1 and Occludin (Fig. 7). These results indicated that CSP-DP could repair intestinal permeability.

Fig. 6.

Effects of CSP-DP on the intestinal homeostasis. (A) The change process of TEER value in the modeling process of Caco-2 monolayer. The effect of CSP-DP on (B) intracellular ROS levels in Caco-2 cells and (C) intracellular MDA contents in LPS-induced intestinal barrier disfunction model.

Fig. 7.

Effects of CSP-DP on the relative mRNA expression (A) ZO-1, (B) Claudin and (C) occludin in LPS-induced intestinal barrier disfunction model.

In addition, DCF fluorescence was implemented to assess the ROS levels in response to LPS and CSP-DP treatment. As exhibited in Fig. 6(C), in the LPS-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction model, CSP could significantly decrease the intracellular ROS generation induced by LPS. MDA is an indicator of lipid peroxidation, whose content reflects the membrane lipid peroxidation degree. The effects of LPS and CSP-DP on MDA content were shown in Fig. 6(D). The change trend of MDA content was consistent with ROS result, indicating CDP-DP could remodel LPS-induced intestinal barrier disfunction.

4. Conclusion

In summary, this study demonstrated that CSP is a high-quality plant protein. Ultrasound-assisted extraction at an appropriate intensity can alter the spatial structure of proteins through mechanical vibration and cavitation, thereby altering their functional and digestive characteristics. Our efforts were aimed at providing a basic understanding of CSP to inspire the efficient utilization of cactus fruit byproducts.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xue Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Baokun Qi: Data curation, Writing – original draft. Shuang Zhang: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Yang Li: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support received from the National Soybean Industrial Technology System of China (CARS-04-PS32).

Contributor Information

Shuang Zhang, Email: szhang@neau.edu.cn.

Yang Li, Email: yangli@neau.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Moussa-Ayoub T.E., Jaeger H., Youssef K., Knorr D., El-Samahy S., Kroh L.W., Rohn S. Technological characteristics and selected bioactive compounds of Opuntia dillenii cactus fruit juice following the impact of pulsed electric field pre-treatment. Food Chem. 2016;210:249–261. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.04.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Mostafa K., El Kharrassi Y., Badreddine A., Andreoletti P., Vamecq J., El Kebbaj M.S., Latruffe N., Lizard G., Nasser B., Cherkaoui-Malki M. Nopal cactus (Opuntia ficus-indica) as a source of bioactive compounds for nutrition, health and disease. Molecules. 2014;19:14879–14901. doi: 10.3390/molecules190914879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stintzing F.C., Schieber A., Carle R. Evaluation of colour properties and chemical quality parameters of cactus juices. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2003;216:303–311. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otalora M.C., Carriazo J.G., Iturriaga L., Nazareno M.A., Osorio C. Microencapsulation of betalains obtained from cactus fruit (Opuntia ficus-indica) by spray drying using cactus cladode mucilage and maltodextrin as encapsulating agents. Food Chem. 2015;187:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.04.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xing Q., Dekker S., Kyriakopoulou K., Boom R.M., Schutyser M. Enhanced nutritional value of chickpea protein concentrate by dry separation and solid state fermentation. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2019;59:102269. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X., Gao W., Zhang J., Zhang H., Li J., He X., Hao M. Subunit, amino acid composition and in vitro digestibility of protein isolates from Chinese kabuli and desi chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) cultivars. Food Res. Int. 2010;43:567–572. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jambrak A.R., Lelas V., Mason T.J., Krešić G., Badanjak M. Physical properties of ultrasound treated soy proteins. J. Food Eng. 2009;93(4):386–393. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang J., Zhu B.o., Liu Y., Xiong Y.L. Interfacial structural role of pH-shifting processed pea protein in the oxidative stability of oil/water emulsions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014;62(7):1683–1691. doi: 10.1021/jf405190h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.B T.X.A., B W.X.A., A M.G., A J.X., B B.L.A., B Y.C.A. Effect of high intensity ultrasound on structure and foaming properties of pea protein isolate. Food Res. Int. 2018;109:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu J.J., Ji H., Chen Y., Zhang Y.F., Zheng X.C., Li S.H., Chen Y. Analysis of the glycosylation products of peanut protein and lactose by cold plasma treatment: solubility and structural characteristics. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020:33129. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.04.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dabbour M.I., He R., Mintah B., Ma H. Changes in functionalities, conformational characteristics and antioxidative capacities of sunflower protein by controlled enzymolysis and ultrasonication action. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;58:104625. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onsaard E., Vittayanont M., Srigam S., McClements D.J. Comparison of properties of oil-in-water emulsions stabilized by coconut cream proteins with those stabilized by whey protein isolate. Food Res. Int. 2006;39(1):78–86. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen L., Ettelaie R., Akhtar M. Improved enzymatic accessibility of peanut protein isolate pre-treated using thermosonication. Food Hydrocoll. 2019;93:308–316. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beveridge T., Toma S.J., Nakai S. Determination of SH- and SS-groups in some food proteins using ellman's reagent. J. Food Sci. 1974;39(1):49–51. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller E.L. Determination of the tryptophan content of feedingstuffs with particular reference to cereals. J Sci Food Agric. 2010;18:381–386. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740180901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang L.i., Zhang X., Wang X., Jin Q., McClements D.J. Influence of dairy emulsifier type and lipid droplet size on gastrointestinal fate of model emulsions: in vitro digestion study. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66(37):9761–9769. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li C., Huang X., Peng Q., Shan Y., Xue F. Physicochemical properties of peanut protein isolate–glucomannan conjugates prepared by ultrasonic treatment. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014;21(5):1722–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X., Liu Y.J., Nian B.B., Cao X.Y., Tan C.P., Liu Y.F., Xu Y.J. Molecular dynamics revealed the effect of epoxy group on triglyceride digestion. Food Chem. 2022;373:131285. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alavi F., Emam-Djomeh Z., Yarmand M.S., Salami M., Momen S., Moosavi-Movahedi A.A. Cold gelation of curcumin loaded whey protein aggregates mixed with k-carrageenan: Impact of gel microstructure on the gastrointestinal fate of curcumin. Food Hydrocoll. 2018;85:267–280. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li X., Nian B.B., Tan C.P., Liu Y.F., Xu Y.J. Deep-frying oil induces cytotoxicity, inflammation and apoptosis on intestinal epithelial cells. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022;102:3160–3168. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.11659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kornet R., Shek C., Venema P., Goot A., Linden E. Substitution of whey protein by pea protein is facilitated by specific fractionation routes. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;117:106691. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ciuti P., Dezhkunov N.V., Francescutto A., Kulak A.I., Iernetti G. Cavitation activity stimulation by low frequency field pulses. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2000;7(4):213–216. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4177(99)00037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang J., Chen J., Xiong Y.L. Structural and emulsifying properties of soy protein isolate subjected to acid and alkaline pH-shifting processes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:7576–7583. doi: 10.1021/jf901585n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang J., Xiong Y.L., Chen J. pH shifting alters solubility characteristics and thermal stability of soy protein isolate and its globulin fractions in different pH, salt concentration, and temperature conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:8035–8042. doi: 10.1021/jf101045b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.C J.O., A X.S., B B.M., C C.F., A I.N. The effect of ultrasound treatment on the structural, physical and emulsifying properties of animal and vegetable proteins. Food Hydrocoll. 2016;53:141–154. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higuera-Barraza O.A., Torres-Arreola W., Ezquerra-Brauer J.M., Cinco-Moroyoqui F.J., Rodríguez Figueroa J.C., Marquez-Ríos E. Effect of pulsed ultrasound on the physicochemical characteristics and emulsifying properties of squid (Dosidicus gigas) mantle proteins. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;38:829–834. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Yanqing, Kong Baohua, Xia Xiufang, Qian L., Diao Xinping. Structural changes of the myofibrillar proteins in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) muscle exposed to a hydroxyl radical-generating system. Process Biochem. 2013;48:863–870. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin J., Okagu O.D., Udenigwe C.C., Ahmedyagoub E.G. Effects of sonication on the in vitro digestibility and structural properties of buckwheat protein isolates. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;70:105348. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li K., Fu L., Zhao Y.Y., Xue S.W., Wang P., Xu X.L., Bai Y.H. Use of high-intensity ultrasound to improve emulsifying properties of chicken myofibrillar protein and enhance the rheological properties and stability of the emulsion. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;98 105275.105271-105275.105211. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li W., Yang H., Coldea T.E., Zhao H. Modification of structural and functional characteristics of brewer's spent grain protein by ultrasound assisted extraction. LWT- Food Sci. Technol. 2020;139:110582. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carbonaro M., Maselli P., Nucara A. Structural aspects of legume proteins and nutraceutical properties. Food Res. Int. 2015;76:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Margheritis E., Terova G., Oyadeyi A.S., Renna M.D., Cinquetti R., Peres A., Bossi E. Characterization of the transport of lysine-containing dipeptides by PepT1 orthologs expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Comparative Biochem. Physiol. Part A. 2013;164:520–528. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]