Message

As clinically actionable genomic lesions are found in almost 30% of pancreatic cancers that can potentially impact management, there has been increased focus on molecular profiling. Although tissue acquisition under endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) guidance is an established diagnostic method, procedural outcomes for comprehensive molecular profiling (CMP) have been variable. In a randomised trial, we found that performing two dedicated passes using the 22-gauge Franseen needle, adopting the fanning and stylet-retraction manoeuvres, yielded optimum specimen from which adequate RNA and DNA could be extracted for CMP in almost 95% of patients with pancreatic cancer.

In more detail

Given the poor outcomes of traditional chemotherapy, there is increased focus on molecular profiling to personalise pancreatic cancer treatment. Recently, CMP tests using next-generation sequencing (NGS) were approved for commercial use. These tests provide clinically relevant information on gene alterations that include both actionable and resistant mutations thereby enabling selection of chemotherapy tailored to individual patients. While the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend EUS as the modality of choice for establishing pathological diagnosis in suspected pancreatic cancer, it is unclear if the technique is also suited for tissue procurement to conduct CMP.1 This is because the volume of tissue obtained using 22-gauge (G) needles is small, viability of DNA extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue is unknown and RNA extraction from pancreatic tissue is more cumbersome and difficult due to enzymatic degradation.2 3 To determine the optimal technique by which adequate DNA and RNA can be procured for CMP studies, we conducted a randomised trial in patients undergoing EUS-guided fine needle biopsy (FNB) of suspected pancreatic cancer.

Patients with pancreatic mass proven to have adenocarcinoma by rapid onsite evaluation at EUS were randomised intra-procedurally to undergo two or three dedicated FNB passes for CMP. Tissue was procured using the 22G Franseen needle (Boston Scientific) adopting evidence-based practices (fanning technique and stylet-retraction manoeuvre) that yield highly cellular tissue.4 5 Genomic DNA and total RNA were simultaneously extracted from FFPE cell blocks (QIAGEN AllPrep).6 The pathology laboratory assessing specimens for CMP was blinded to the randomisation assignment. Main outcome was the proportion of specimens from which adequate DNA and RNA could be extracted for CMP and the sample size was estimated at 16 per group (total sample size of 33 to account for a 5% drop out rate).

Thirty-three patients diagnosed to have pancreatic adenocarcinoma at EUS-FNB were randomised to undergo two (n=17) or three (n=16) FNB passes (online supplemental figure 1, table 1). While sufficient DNA was extracted from all 33 (100%) FFPE cell blocks, adequate RNA was extracted from 15 of 16 FFPE cell blocks in the three pass (93.8%) versus 16 of 17 in the two pass cohort (94.1%) (p=0.99) with no significant difference in the median concentration of DNA (two pass 9.6 ng/µL (IQR 2.8–16.6) vs three pass 7.8 ng/µL (IQR 5.0–10.8); p=0.228) or RNA (two pass 36.5 ng/µL (IQR 11.4–52.5) vs three pass 30.5 ng/µL (IQR 15.2–39.8); p=0.374) between groups (table 2). While DNA mutations were identified in all 33 specimens, 12.1% of the study cohort had clinically relevant or actionable mutations that included BRCA1 in one, KRAS G12C mutations in two and somatic oncogene RNA fusion (LDAH-ETV1) in one (online supplemental table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and procedure details

| Two passes | Three passes | P value | ||

| (n=17) | (n=16) | |||

| Age: (years) | Mean (SD) | 76.2 (7.6) | 77.9 (7.9) | |

| Median | 77 | 80 | 0.471 | |

| IQR | 72–80 | 72–83 | ||

| Range | 61–88 | 60–92 | ||

| Gender: n (%) | Female | 9 (52.9) | 11 (68.7) | 0.353 |

| Male | 8 (47.1) | 5 (31.3) | ||

| Ethnicity: n (%) | Black | 3 (17.6) | 1 (6.3) | 0.584 |

| Caucasian | 12 (70.6) | 14 (87.5) | ||

| Hispanic | 2 (11.8) | 1 (6.3) | ||

| Pancreatic mass size (cm): | Mean (SD) | 3.8 (0.9) | 3.6 (1.1) | |

| Median | 3.7 | 3.6 | 0.649 | |

| IQR | 3.0–4.0 | 2.8–4.9 | ||

| Range | 2.0–5.5 | 1.8–5.0 | ||

| Mass location: n (%) | Head/uncinate | 14 (82.4) | 8 (50.0) | 0.071 |

| Neck/body/tail | 3 (17.6) | 8 (50.0) | ||

| Distant metastasis: n (%)* | 4 (23.5) | 4 (25.0) | 0.999 | |

| Technical success: n (%) | 17 (100) | 16 (100) | 0.999 | |

| Adverse events: n (%)† | 1 (5.9) | 1 (6.3) | 0.999 |

*Distant metastasis: Two pass group—peritoneal carcinomatosis (n=1), liver (n=3). Three pass group—liver (n=4).

†Adverse events: one patient in the two pass group died from underlying cancer in hospice care 1 week after the procedure; one patient in the three pass group had a duodenal perforation during Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for biliary stricture and underwent surgical repair.

Table 2.

Details on specimen procured and molecular profiling

| Two passes | Three passes | P value | ||

| (n=17) | (n=16) | |||

| Diagnostic adequacy on onsite evaluation: n (%) | 17 (100) | 16 (100) | 0.999 | |

| Diagnostic adequacy on cell block: n (%) | 17 (100) | 16 (100) | 0.999 | |

| Specimen bloodiness: n (%) | Low | 8 (47.1) | 7 (43.7) | 0.999 |

| Moderate | 8 (47.1) | 8 (50.0) | ||

| High | 1 (5.9) | 1 (6.3) | ||

| Adequate DNA extracted: n (%) | 17 (100) | 16 (100) | 0.999 | |

| DNA concentration: ng/µL | Mean (SD) | 10.7 (7.1) | 7.9 (4.4) | |

| Median | 9.6 | 7.8 | 0.228 | |

| IQR | 2.8–16.6 | 5.0–10.8 | ||

| Range | 0.87–20.9 | 0.68–16.0 | ||

| Adequate RNA extracted: n (%) | 16 (94.1) | 15 (93.8) | 0.999 | |

| RNA concentration: ng/µL | Mean (SD) | 37.1 (26.5) | 28.9 (13.2) | |

| Median | 36.5 | 30.5 | 0.374 | |

| IQR | 11.4–52.5 | 15.2–39.8 | ||

| Range | 3.6–97.0 | 9.9–49.0 | ||

gutjnl-2023-329495supp001.pdf (477.4KB, pdf)

Comments

The NCCN guidelines recommend that germline testing be considered in all patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and molecular analysis in those patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease.1 Germline testing and molecular profiling carry important implications for screening and treatment. Molecular profiling enables better selection of chemotherapy regimens tailored to individual patients thereby improving treatment outcomes while at same time avoiding unnecessary treatment in patients in whom chemotherapy may be ineffective.

Although NGS can sequence multiple genes, acquisition of sufficient tissue is a mandatory requisite for testing. While surgical biopsies can yield larger specimens, only 20% of patients with pancreatic cancer are potential surgical candidates. Therefore, several studies have explored surrogacy of EUS procured samples for surgically resected specimens in NGS. These studies have shown modest concordance with reported adequacy ranging from 60% to 100%.7 Given lack of knowledge on optimum needle gauge, tailored procedural manoeuvres, requisite number of passes, specimen processing methods and their correlation to extracted DNA and RNA, the debate on effectiveness of EUS-guided tissue acquisition for molecular profiling persists. Addressing these questions will enable reliable procurement of adequate tissue for CMP, expedite oncological care and minimise financial loss due to suboptimal sampling as state-of-the-art NGS testing can cost upward of US $4000.

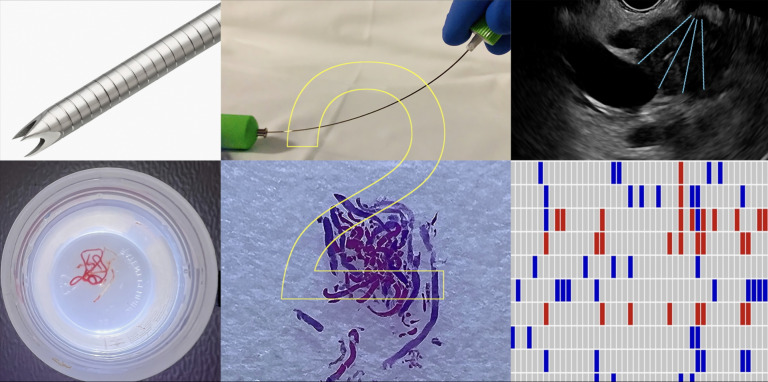

How are the findings of the present study important and why is it relevant? One, our study has proposed a specific needle gauge, identified procedural manoeuvres and determined the finite number of biopsies required for reliable procurement of tissue for CMP (figure 1, online supplemental video 1). This study showed that performing two passes at EUS-FNB yielded samples that were adequate for CMP, with no significant difference between two and three passes, likely due to the tumour becoming significantly bloody after two passes that then led to suboptimal extraction of RNA and DNA. Two, FFPE cell blocks are commonly used worldwide for specimen processing and the present study demonstrates that CMP testing can be performed satisfactorily from these cell blocks. Three, although we were able to create 16–20 FFPE cell blocks with tissue obtained from two dedicated FNB passes, only 50–100 ng of RNA or DNA were required for conducting assays which could be derived from 10 or fewer cell blocks. Therefore, we believe that by adopting our proposed method, testing for CMP can be undertaken using any commercially available NGS product that may require a larger volume of DNA or RNA. Four, 12% of the study cohort had clinically relevant or actionable mutations that impacted management. While DNA mutations were identified in all specimens, one with BRCA1 positivity warranted oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy, two with rare G12C mutation could be targeted using sotorasib or adagrasib and presence of LDAH-ETV1 somatic oncogene RNA fusion in one patient indicated desmoplastic stromal expansion and metastatic progression of pancreatic cancer denoting futility of aggressive chemotherapy.

Figure 1.

Graphical abstract demonstrating, Franseen-tip needle, stylet-retraction technique and fanning manoeuvre (upper panel, left to right); pancreatic cancer tissue collected at endoscopic ultrasound in 10% formalin, formalin-fixed paraffin embedded cell block and molecular profiling (lower panel, left to right), can be achieved with two dedicated fine needle biopsy passes.

gutjnl-2023-329495supp002.mp4 (274.7MB, mp4)

There are a few limitations to this study. One, we evaluated only the Franseen FNB needle and therefore the outcomes may not be applicable to other FNB needle types. Two, the sample size was estimated to examine the difference between two and three FNB passes and not just a single pass because we believe that a single pass may not procure adequate tissue for NGS testing when using some commercially available tests such as FoundationOne CDx that evaluates for nearly 300 mutations.

In conclusion, we propose an evidence-based EUS technique that can standardise reliable procurement of tissue for comprehensive molecular profiling in pancreatic cancer. This development is likely to further advance the role of EUS in the oncological management of patients.

Trial registration number

Footnotes

Contributors: JYB: Study design, endoscopist performing procedures in the study, statistical analysis, interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, critical revision of manuscript. SV: Study concept and design, endoscopist performing procedures in the study, interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, critical revision of manuscript. RH: Endoscopist performing procedures in the study, critical revision of manuscript. UN: Endoscopist performing procedures in the study, critical revision of manuscript. CMW: Critical revision of manuscript. NJ: Cytopathologist performing molecular profiling, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of manuscript. AS: Cytopathologist performing molecular profiling, critical revision of manuscript. KK: Cytopathology technician preparing slides and cell blocks in the study, critical revision of manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: JYB: Consultant for Olympus America and Boston Scientific Corporation. SV: Consultant for Boston Scientific, Olympus America and Medtronic. RH: Consultant for Boston Scientific, Olympus America and Medtronic. UN: Consultant for Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb and GIE Medical. NJ, AS, KK and CMW have no disclosures to declare.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Orlando Health Institutional Review - Approval Notice 1741103. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Tempero MA, Malafa MP, Al-Hawary M, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2021;19:439–57. 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Caixeiro NJ, Lai K, Lee CS. Quality assessment and preservation of RNA from Biobank tissue specimens: a systematic review. J Clin Pathol 2016;69:260–5. 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arreaza G, Qiu P, Pang L, et al. Pre-analytical considerations for successful next-generation sequencing (NGS): challenges and opportunities for formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tumor tissue (FFPE) samples. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17:579. 10.3390/ijms17091579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bang JY, Magee SH, Ramesh J, et al. Randomized trial comparing fanning with standard technique for endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of solid pancreatic mass lesions. Endoscopy 2013;45:445–50. 10.1055/s-0032-1326268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Young Bang J, Krall K, Jhala N, et al. Comparing needles and methods of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy to optimize specimen quality and diagnostic accuracy for patients with pancreatic masses in a randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:825–835.S1542-3565(20)30905-8. 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Patel PG, Selvarajah S, Guérard K-P, et al. Reliability and performance of commercial RNA and DNA extraction kits for FFPE tissue cores. PLoS One 2017;12:e0179732. 10.1371/journal.pone.0179732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Imaoka H, Sasaki M, Hashimoto Y, et al. New era of endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition: next-generation sequencing by endoscopic ultrasound-guided sampling for pancreatic cancer. J Clin Med 2019;8:1173. 10.3390/jcm8081173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gutjnl-2023-329495supp001.pdf (477.4KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2023-329495supp002.mp4 (274.7MB, mp4)