Abstract

Background

Identifying subjects at risk of imminent psoriatic arthritis (PsA) would allow these subjects to participate in therapeutic interventions to delay or prevent PsA development.

Methods

A systematic literature review (SLR) was conducted in 2021 in Medline, Embase, PubMed, Central databases and international congress abstracts (PROSPERO CRD42022255102). All articles reporting the characteristics of patients transitioning from psoriasis (PsO) to PsA and from undifferentiated arthritis (UA) to PsA were included. Clinical and imaging characteristics were collated before PsA onset and at time of PsA diagnosis.

Results

Eighteen of 23 576 references evaluated for PsO/PsA transition were analysed; 14 were cohort studies, 2 case-control studies. Two SLRs were used to enrich the project but were not analysed per se. Of 7873 references focusing on UA to PsA, 3 studies were included. Meta-analysis was not possible due to excessive data heterogeneity. Patients with PsO who developed PsA often reported joint pain, joint tenderness and functional limitations. Arthralgia (PsO, n=669; incident PsA, n=99) was associated with subsequent PsA development. On imaging, subclinical enthesopathy (PsO=325; Incident PsA=39) appeared linked to later PsA development. At the time of PsA onset (incident PsA, N=214), peripheral arthritis, mainly oligo-arthritis (ie, the mean number of swollen joints ranged from 1.5 to 3.2), was the most frequent pattern of clinical presentation.

Conclusions

Joint pain, arthralgia and entheseal involvement detected by imaging were frequent in individuals with PsO at risk for imminent PsA. Very early PsA was mainly oligoarticular. This review informed a EULAR taskforce on transition to PsA.

Keywords: arthritis; arthritis, psoriatic; inflammation

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

The information regarding the transition from psoriasis or undifferentiated arthritis to psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is fragmented and limited.

Improving the knowledge base on the phases before PsA onset in subjects with psoriasis could facilitate therapeutic interventions to delay or prevent PsA development.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Patients with psoriasis reported joint pain, joint tenderness and functional limitations before the PsA diagnosis.

Enthesopathy detected by imaging appeared linked to later PsA development.

Peripheral arthritis, mainly oligoarthritis, is the usual clinical pattern of PsA presentation.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This review informed the EULAR Points to Consider for the definition of clinical and imaging features suspicious for progression to Psoriatic Arthritis.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) mostly develops in patients with an established diagnosis of psoriasis (PsO).1 The incidence of PsA after the onset of PsO increases with time, reaching up to 20% after 30 years.1 2 Nail, scalp, inverse psoriasis and cutaneous disease severity have all been linked to a higher risk of subsequent PsA development.3 Among comorbidities, obesity is associated with PsA development.4 5 Furthermore, from a potential genetic perspective, first-degree relatives with PsA also contribute to an increased risk.6 Symptoms linked to joints or to general health status reported by people with PsO (eg, arthralgia, morning stiffness, fatigue) may be clinical markers of imminent PsA development.7–11

An expert group has recently proposed that there are three clinical stages after PsO onset and before clinically-detected PsA.12 13 In this proposed classification, there are two initial asymptomatic phases, first with aberrant activation of the immune system, then with subclinical signs of inflammation (eg, imaging abnormalities and/or elevation of acute phase reactants, C reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate). Indeed, people with PsO with subclinical inflammation detected by imaging appear to be more likely to develop PsA.14 Then, a symptomatic transition phase may exist characterised by arthralgia and fatigue.7 8 15 However, there remains a lack of definitive longitudinal data corroborating this hypothesis, though some studies in people with PsO affected by arthralgia, indicate an increased risk for later PsA development.14 The prodromal phase of imminent PsA is difficult to diagnose due to non-specific symptoms and mimickers, such as incipient or concomitant osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia or chronic pain related to psoriatic comorbidities.

The identification of people with PsO who are at risk of developing PsA could facilitate PsA prevention strategy development.16 17 In a dermatological setting, the identification of people with PsO in their transition phase could offer the opportunity for PsA interception, without extra treatment costs, since a PsO subject in transition needs a tailored therapy that could work both for skin and joints. In a rheumatological setting, the identification of clinical and imaging predictors of PsA could encourage a dedicated follow-up and an early start of systemic treatment at the onset of PsA. And finally, a better knowledge of the characteristics of very early PsA would be useful, in the context of the concept of a window-of-opportunity.18 To identify patients with very early PsA, it is of interest to explore characteristics of patients with undifferentiated arthritis (UA) later diagnosed as PsA.19 A EULAR task force was convened in 2021 to better understand both the preclinical and very early phases of PsA; ultimately geared towards PsA prevention strategies, that is, in a well-defined PsO population, geared towards therapeutic intervention that could attenuate, delay, or prevent PsA development. The EULAR task force proposed that three distinct stages were relevant to the prevention of PsA: (1) people with PsO at higher risk of PsA; (2) subclinical PsA and (3) clinical PsA. (see accompanying paper).

The objective of the present systematic literature review (SLR) was to generate data to inform this EULAR taskforce, by collating the characteristics of patients transitioning from PsO to PsA and from UA to PsA and of patients with newly onset clinical PsA.

Methods

This SLR followed the EULAR operating procedures for SLRs and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines as explained on Prospero (CRD42022255102).20

The key questions of the SLR were defined by the EULAR taskforce in June 2021, namely: (1) What are the are the symptoms, objective signs, lab tests, imaging features and other characteristics in patients with ‘newly onset’ adult PsA with a previous diagnosis of PsO? (2) In ‘early UA ultimately classified as PsA’ what are the baseline (ie, at the diagnosis) symptoms, objective signs, lab tests, imaging features and other characteristics? The rationale behind this was that the UA phenotype where PsA was subsequently confirmed would represent the earliest PsA manifestations thus allowing to explore the very early phases of PsA.

Data sources

A literature search strategy was designed by two of the authors (GDM and AZ) with the support of the expert health librarian (JE) (online supplemental table 1). Relevant keywords concerning PsO, PsA, early PsA, new onset PsA and UA were applied in Medline, Embase, PubMed and Central databases (up to October 2021). Abstracts from annual congress of the European Congress of Rheumatology and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Congress were also explored. Finally, additional relevant articles were identified though discussions with the expert EULAR taskforce members (‘hand search’).

rmdopen-2023-003143supp001.pdf (62.3KB, pdf)

Study selection

Studies retrieved from the searches were recorded on a central database (covidence.org). Two investigators (GDM and AZ) independently screened all titles. Abstracts of titles identified as potentially eligible for inclusion were then independently assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria by the two investigators. Disagreements were settled by discussion between the two investigators and a third investigator (DMG) where required.

Selection criteria

Publications were selected if they reported data on patients who transitioned from a stage of PsO or UA to a new diagnosis of PsA (according to clinical diagnosis or classification criteria for PsA(CASPAR)). We selected focusing on features characterising the subclinical PsA and new onset clinical PsA (see accompanying main paper).

The identification of the traditional risk factors for PsA development (eg, severe skin PsO, nail involvement) was out of the scope of this SLR.

Eligible references could include cohort (prospective and retrospective) and case-control study designs. In the cohort studies, the PsA diagnosis must be excluded at the baseline and the final PsA diagnosis must be clinically confirmed (not suspected). When focusing on the transition from PsO to PsA, in case-control studies, the cases were incident PsA or prevalent PsA with onset of PsO before PsA development. Studies had to be published in English. Pre-existing SLRs were used to enrich the project but were not analysed per se. Case reports, comments and editorials were excluded.

Data collection

Two authors (GDM, AZ) extracted the data, supervised by the methodologists (LG, XB). Data extracted included study design, population, incidence rate (IR) of PsA, prodromal features before PsA onset, objective signs, clinical phenotypes, imaging features before or at the onset of PsA.

Statistics

IRs of PsA development in patients with PsO were calculated for each study, based on the mean follow-up duration and the number of cases, for 100 patient-years. The results were synthesised qualitatively for each clinical question. No meta-analysis was intended, due to the heterogeneity across studies in terms of population, interventions and outcomes measured.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment of the selected publications was performed using the Newcastle-Ottowa Scale (NOS),21 two of the investigators (GDM and AZ) independently. Any disagreement between the two investigators was resolved by a third independent investigator (DMG). The NOS scores studies according to three items: selection, comparability and outcome. The final score (range 0–9) is the sum of the item scoring. The higher the score, the better the methodological quality and the lower risk of bias (RoB); studies with ≥6 stars were considered low RoB, those with 4 or 5 stars intermediate RoB and those with <4 stars at high RoB.

Results

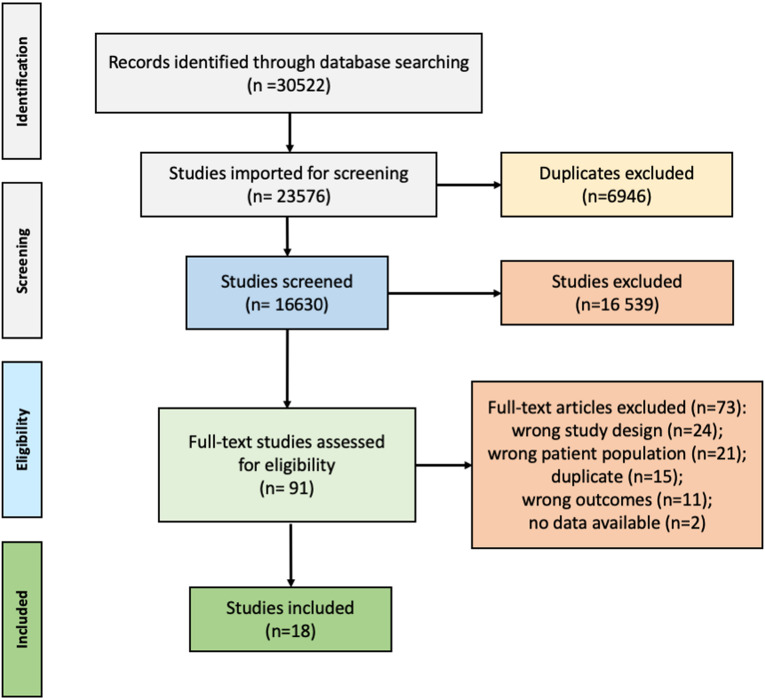

Regarding PsO/PsA transition, of 30 522 references, 18 studies were included of which 10 cohort studies (6 prospective, 4 retrospective), 1 case-control study, 1 Bayesian network study, 4 abstracts (2 from the ACR congress and 2 from the EULAR congress) and 2 SLRs were used to inform the taskforce.7–10 14 15 22–33 The PRISMA flow chart is shown in figure 1. Details on the included studies are available in online supplemental file 2.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for article selection according to the PRISMA guidelines regarding the first key question of the SLR: What are the symptoms, objective signs, lab tests, imaging features and other characteristics in patients with ‘newly onset’ adult PsA with a previous diagnosis of PsO? PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; SLR, systematic literature review.

rmdopen-2023-003143supp002.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)

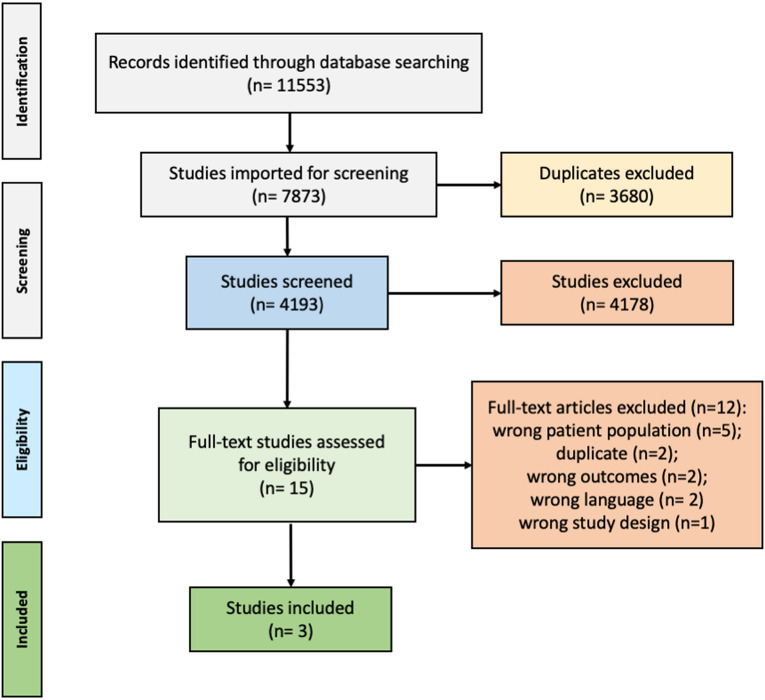

Regarding UA/PsA transition, of 7873 references focusing on UA to PsA, 3 studies were included of which 1 was a retrospective cohort study, 1 a case-control study and 1 in abstract form.34–36 The PRISMA flow chart is shown in figure 2. The breakdown presentation of the included studies is available in online supplemental file 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart for article selection according to the PRISMA guidelines regarding the second key question of the SLR In ‘early UA ultimately classified as PsA’: what are the baseline (ie, at the diagnosis) symptoms, objective signs, lab tests, imaging features and other characteristics? The rationale behind this was that the UA phenotype where PsA was subsequently confirmed represented the earliest PsA manifestation. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; SLR, systematic literature review; UA, undifferentiated arthritis.

Incidence rate of PsA development and the new diagnosis of PsA in patients with PsO

Among the original articles, 9 out of 12 studies (PsO, n=4019; incident PsA, n=577) reported the IR of PsA development in patients with PsO (table 1). The IR per 100 patient-years ranged from 1.6 to 24.4. This wide range may be based on the type of PsO population at baseline, since the studies with higher IR used imaging as predictor of short term PsA development.8–10 These studies with higher IRs enrolled numerous patients with arthralgia (between 38% and 52% of the study population), in the absence of clinical PsA, and therefore a higher IR compared with patients with PsO was expected.8 10 Focusing on the subclinical PsA (selected for the presence of arthralgia) the IR ranged from 10.98 to 34.3.10

Table 1.

The incidence rate of PsA development in patients with PsO

| Author, year | Population (n=) | Events (n=) | Follow-up | Study type | Incidence rate (IR) per 100 patients-years | Definition of PsA |

| Faustini et al, 201610* | 41 | 12 | 1.2 | Cohort prospective | 24.4 | Clinical diagnosis and CASPAR+ |

| Simon et al, 20209* | 114 | 24 | 2.3 | Cohort prospective | 9.7 | Clinical diagnosis and CASPAR+ |

| Zabotti et al, 20198* | 102 | 6 | 1.2 | Cohort prospective | 4.9 | Clinical diagnosis and CASPAR+ |

| Elnady et al, 201923 | 109 | 9 | 2 | Cohort prospective | 4.3 | Clinical diagnosis and CASPAR+ |

| Eder et al, 20177 | 410 | 57 | 3.8 | Cohort prospective | 3.7 | Clinical diagnosis and CASPAR+ |

| Eder et al, 201615 | 433 | 51 | 4.1 | Cohort prospective | 2.7 | Clinical diagnosis and CASPAR+ |

| Belman et al, 202125 | 627 | 128 | 7.7 | Cohort retrospective | 2.7 | Clinical diagnosis |

| Acosta et al, 202224 | 1719 | 239 | 7.3 | Cohort retrospective | 1.9 | Clinical diagnosis and/or CASPAR + |

| Gisondi et al, 202226 | 464 | 51 | 6.9 | Cohort retrospective | 1.6 | CASPAR+ |

| Balato et al, 202133 | 285 | 22 | Not reported | Cohort retrospective | / | Clinical diagnosis |

| Abji et al, 202122 | 40 | 16 | Not applicable | Case-control | / | CASPAR+ |

| Green et al, 202132 | 90 189 | 1409 | Not reported | Bayesian network | / | PsA code and GP evaluation |

The IRs subdivided for the presence of arthralgia were as follows: Faustini, 2016: PsO without arthralgia=IR 17.4 (5.6–40.5]; PsO with arthralgia=IR 34.3 (13.8–70.7); Zabotti, 2019: PsO without arthralgia=IR 1.34 (0.0–7.5); PsO with arthralgia=IR 10.9 (3.5–25.4); Simon, 2020: PsO without arthralgia=IR 5.9 (2.4–12.2); PsO with arthralgia=IR 12.5 (6.2–22.4).

*Studies including patients with PsO with arthralgia.

IR, incidence rate; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PsO, psoriasis.

Clinical characterisation of patients with PsO prior to PsA onset

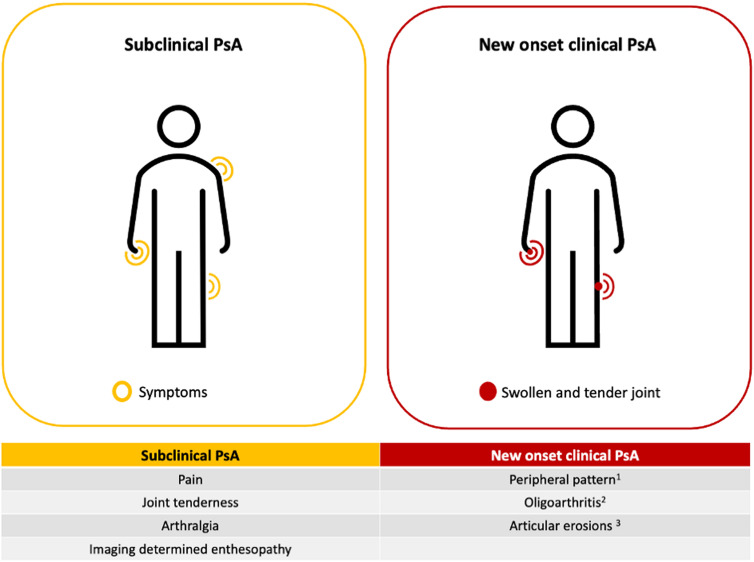

Five articles7–10 32 focusing on the symptoms detected before PsA onset aimed to identify potential predictors of PsA development in patients with PsO and features of subclinical PsA (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Major features of subclinical PsA and new onset clinical PsA. The features characterising the subclinical PsA (ie, pain, joint tenderness, arthralgia and imaging determined enthesopathy) could be considered as short-term predictors of PsA development. No target joints resulted as predictors of PsA development or typical for PsA onset. 1Peripheral arthritis was the most prevalent pattern of presentation with rates ranging from 50% to 100%. 2The mean number of swollen joints at the onset of PsA ranged from 1.5 to 3.2. 3Articular erosions detected by CR were detected between 23 and 33% of patients with newly diagnosed PsA . CR, conventional radiography; PsA, psoriatic arthritis.

Patients developing PsA during the follow-up had higher Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) pain at baseline7–10 and joint tenderness8–10 (table 2). One study evaluated the variations of symptoms before PsA diagnosis in patients with PsO; in Eder et al, an increase in the levels of pain, fatigue, morning stiffness and a worsening of physical function over time were associated to the development of PsA.7

Table 2.

Clinical and imaging characterisation of patients with PsO prior to PsA onset

| Positive association with PsA development | No association with PsA development | |

| Pain | 4 studies (PsO=667; incident PsA=99) |

0 |

| Joint tenderness | 3 studies (PsO=257; incident PsA=42) |

0 |

| Arthralgia | 4 studies (1 study only in female)* (PsO=667; incident PsA=99) |

1 study (in male)* (PsO=410; incident PsA=57) |

| Subclinical enthesopathy (US in 2 studies, pQCT) | 3 studies (PsO=325; incident PsA=39) |

0 |

| Subclinical synovitis (US or MRI) | 1 study (PsO=109; incident PsA=9) |

2 studies (PsO=143; incident PsA=18) |

| Subclinical tenosynovitis (US or MRI) | 0 | 2 studies (PsO=143; incident PsA=18) |

*The definition of arthralgia used in these studies were different: in Faustini et al, this was the presence of at least one tender joints; in Zabotti et al, it was recent onset of non-inflammatory joint and/or entheseal pai and in Simon et al in terms of VAS and tender joints.

pQCT, peripheral quantitative tomography; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PsO, psoriasis; US, ultrasonography.

In four prospective studies (PsO, n=669; incident PsA, n=99) the presence of arthralgia without clinical evidence of PsA was associated with subsequent PsA development.7–10 One of these studies showed that arthralgia in women, but not men, was associated with subsequent development of PsA.7

In a Bayesian network study, Green et al found that over one-fifth of the patients with PsO who went on to develop PsA visited their general practitioners with musculoskeletal-related symptoms during the 5 years prior to their diagnosis of PsA.32 This proportion gradually increased and reached over 57% in the 6 months immediately preceding the diagnosis.32 Previous SLR also concluded that the risk of PsA development in PsO with arthralgia was about two times greater than in subjects without arthralgia (pooled risk ratio 2.15 (95% CI 1.16 to 3.99)).14

Imaging characterisation of patients with PsO prior to PsA onset

Four cohort studies explored the use of imaging before PsA onset (PsO, n=366; incident PsA, n=51).8–10 23 In three out of four studies, the PsO population included subjects with arthralgia and the duration of follow-up was short, between 1.2 and 2.3 years. All of these studies were limited by the fact that imaging examination was performed only at enrolment. Subclinical, sonographic determined enthesopathy in two studies8 23 and structural entheseal lesion detected by peripheral quantitative CT in one study,9 emerged as a potential imaging predictor of PsA (PsO=325; Incident PsA=39)8 9 23 (table 2). There was conflicting evidence regarding subclinical synovitis, with one study in favour23 and two studies against.8 10 Subclinical tenosynovitis was associated with the presence of clinical arthralgia in patients with PsO8 but not associated with later PsA development in two studies.8 10

Clinical and imaging characterisation of new onset clinical PsA

Six articles7 9 15 23 26 33 addressed the clinical phenotypes of presentation of PsA (PsO, n=1815; incident PsA, n=214). In all of these studies, peripheral arthritis was the most prevalent pattern of presentation with rates ranging from 50%33 to 100%23 (table 3, figure 3).

Table 3.

Clinical and imaging features at the PsA onset

| Studies reporting the clinical features at PsA onset | Studies not reporting the clinical features at PsA onset | |

| Peripheral arthritis (as major pattern of clinical presentation) | 6 studies (PsO n=1815; incident PsA=214) | 0 |

| Oligoarthritis (as major pattern of clinical presentation) | 3 studies (PsO n=1307; incident PsA=159) | 0 |

| Radiographic changes typical for PsA (as usual radiographic feature of presentation >25% of cases) | 3 studies (PsO n=975; incident PsA=114) | 0 |

| Axial involvement (as less frequent pattern of clinical presentation) | 4 studies (PsO n=1382; incident PsA=163) | 1 study (PsO n=433; incident PsA=50) |

| Dactylitis (as usual clinical feature of presentation, >25% of cases) | 1 study (PsO n=285; incident PsA=22) | 4 studies (PsO n=1421; incident PsA=183) |

| Enthesitis (as usual clinical feature of presentation, >25% of cases) | 1 study (PsO n=285; incident PsA=22) | 4 studies (PsO n=1421; incident PsA=183) |

PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PsO, psoriasis.

Among peripheral arthritis, oligoarthritis was more frequently reported7 15 26 (PsO, n=1307; incident PsA, n=159) and in the studies reporting the mean number of involved joints, it ranged from 1.515 to 3.226 for swollen joints and from 2.815 to 2.926 for tender joints.

In Abji et al,37 it was expressed as a mean number of active joints of 1.5. Among the other musculoskeletal domains of psoriatic disease, dactylitis was present at the onset in between 4% and 20% of new onset PsA,9 26 enthesitis between 2% and 21 %9 15 and axial involvement between 4% and 18%7 9 (table 3). At the PsA onset, articular erosions detected by conventional radiography (CR) were detected between 23% and 33% of patients with newly diagnosed PsA.7 15 28 Focusing on axial involvement, in Eder et al, 41% of the patients had signs of sacroiliitis or spondylitis on imaging (CR or MRI).15

Regarding the clinical diagnosis of PsA, in 6 out of 12 (50%) selected full papers (PsO, n=1209; incident PsA, n=159), the combination of clinical diagnosis and the fulfilment of CASPAR criteria (using the threshold >3) was used to define the development of PsA cases.7–10 15 23 The clinical diagnosis of PsA made by one or more rheumatologist was selected for the definition of PsA in 9 out of 12 (75%) studies, and in 5 out of 9 (55.5%) imaging using ultrasound/MRI or CR was used to corroborate the diagnosis.7 9 15 23 33

Clinical and Imaging characterisation of UA ultimately classified as PsA

The SLR retrieved no information regarding the baseline (ie, at the UA diagnosis of patients later classified as PsA) symptoms, objective signs, lab tests and imaging features.

Clinical and Imaging characterisation of new onset PsA from UA

Information regarding the clinical features at the PsA onset in patients with a previous diagnosis of UA is limited. In Cuervo et al, the clinical phenotype at PsA diagnosis was mainly peripheral arthritis with an oligo-articular pattern in the majority of cases (PsA cases, n=12; Monarthritis in 33% and oligoarthritis in 58%). At the onset of PsA, the mean Swollen Joint Count (SJC) was 1.3 joints while the mean TJC was 1.5.34 Furthermore, the authors found that UA later developing PsA, when compared with UA later developing rheumatoid arthritis (RA), had more mono-oligoarthritis and the articular disease was more localised and intermittent. In Exposito-Perez et al,36 peripheral involvement was present in all new PsA diagnosis. Regarding imaging at PsA onset, data were derived only in one study, Paalaneen et al (PsA cases, n=46) in which juxta-articular new bone formation were found in 20% and pencil in cup deformities in 5%.35

Discussion

The present findings are in broad agreement with prior literature that musculoskeletal symptoms and imaging abnormalities are present in PsO subjects at risk for PsA development.

A key component of PsA prevention and interception strategies includes a definition of when a patient has actually transitioned from PsO to PsA.

We looked at both PsO cases that developed PsA and also subjects with isolated UA who later developed psoriasis and hence were diagnosed as PsA and found that synovitis in a limited number of joints was the first PsA features.

Our SLR highlights the fragmentary emerging knowledge of PsA development in PsO subjects and highlights how clinical patterns of PsO mainly joint symptoms and imaging are bringing clarity to the early phases of clinical PsA development.

Many methodological limitations and relevant biases have emerged from this assessment of the available literature. One such potential issue is a lack of standardisation of the definition of PsA onset and related diagnostic/classification criteria. Similarly, lack of standardisation affected the outcomes that authors chose to report across the studies assessed in this SLR, also implying a higher risk of observer bias among the studies.

Most importantly, though, the studies conducted so far rarely had a prospective design that would encompass data collection (including clinical/imaging evaluation) at regular intervals before PsA onset. This led to a relative paucity of longitudinal studies and a near-complete absence of longitudinal imaging studies to define transition in granular detail, to allow insight on potential markers (either biomarkers or imaging features) of future PsA development in PsO subjects.

Furthermore, the selection bias is a major issue in the field of transition, since patients with PsO, usually enrolled in a dermatological setting, can display peculiar clinical phenotypes (eg, moderate to severe PsO, involvement of nails or of sensitive areas), while those with mild skin involvement can be less represented.

Given the absence of the equivalent of the predictive value of an ACPA test in RA, it is evident that much work needs to be done in the space of transition from PsO to PsA in order to accurately predict PsA development towards the development of better prevention strategies.

The CASPAR criteria may be suboptimal for the earliest phases of PsA recognition where radiographic changes are absent in the majority of cases.38 Also, unlike early RA which is very synovial centric, the early phase of PsA can display enthesitis and osteitis that encompasses both the peripheral and difficult to clinically access axial skeleton.

Despite this, our SLR points to the importance of an oligoarticular synovitis development that can be used to facilitate a definite diagnosis of PsA as an outcome measure for clinical trials. This aspect of the SLR was used to facilitate a working definition of new onset PsA in the accompanying EULAR Points to consider document. Given that synovitis is the predominant phenotype and is highly prevalent at clinical diagnosis, it appears to be a useful tool for PsA diagnosis.

In conclusion, the characterisation of the transitioning features from PsO to PsA is critical both on a scientific level, to improve our understanding of the pathobiology of PsA and on a pragmatic-clinical level, to improve our ability to prevent or intercept PsA development. This SLR has served to bring together this preliminary information and has informed the guidance provided in the EULAR points to consider in this key area of transition to PsA.

Footnotes

GDM and AZ contributed equally.

DGM and LG contributed equally.

Contributors: GDM and AZ extracted the data for the SLR. JE developed the search strategies. GDM, AZ, DGM and LG wrote the first version of the manuscript, and all authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. AZ is the guarantor.

Funding: Funded by EULAR grant QoC 002.

Competing interests: AZ: Speakers bureau: AbbVie, Novartis, Janssen, Lilly, UCB, Amgen, Paid instructor for: AbbVie, Novartis, UCB. GDM: Speakers bureau: Novartis, Janssen. LG: Consultant of: AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Celltrion, Galapagos, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sandoz, UCB, Grant/research support from: Sandoz, UCB. XB: Speakers bureau: Abbvie, BMS, MSD, Sandoz, Novartis, Pfizer, Galapagos, UCB, Lilly, Paid instructor, for: Abbvie, BMS, MSD, Sandoz, Novartis, Pfizer, Galapagos, UCB, Lilly, Consultant of: Abbvie, BMS, MSD, Sandoz, Novartis, Pfizer, Galapagos, UCB, Lilly, Grant/research support from: Abbvie, MSD, Novartis, Editorial Board Member of Annals of Rheumatic Diseases, ASAS President DA received grants, speaker fees, or consultancy fees from Abbvie, Gilead, Galapagos, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Sandoz and Sanofi. AI: Speakers bureau: Abbvie, MSD, Alfasigma, Celltrion, BMS, Celgene, Eli-Lilly, Sanofi Genzyme, Pfizer, Galapagos, Gilead, Novartis, SOBI, Janssen, Grant/research support from: Pfizer, Abbvie; Leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group, Novartis, EULAR President, Member of the EULAR Board, Member of EULAR Advocacy Committee. PG: Speakers bureau Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, UCB, Sanofi, Pfizer, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Jannsen, Leo pharma. JSS: Consulting fees: Abbvie, Galapagos/Gilead, Novartis-Sandoz, BMS, Samsung Sanofi, Chugai R-Pharma, Lilly; Payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events: Samsung, Lilly, R-Pharma, Chugai, MSD, Janssen Novartis-Sandoz. DGM: Speakers bureau: AbbVie, Celgene, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB, Consultant of: AbbVie, Celgene, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB, Grant/research support from: AbbVie, Celgene, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Author note: DGM and LG are joint last authors.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Gladman DD, Antoni C, Mease P, et al. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, clinical features, course, and outcome. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:ii14–7. 10.1136/ard.2004.032482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of Psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80:251–65. 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson FC, Icen M, Crowson CS, et al. Incidence and clinical predictors of Psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:233–9. 10.1002/art.24172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jon Love T, Zhu Y, Zhang Y, et al. Obesity and the risk of Psoriatic arthritis: a population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1273–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green A, Shaddick G, Charlton R, et al. Modifiable risk factors and the development of Psoriatic arthritis in people with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2020;182:714–20. 10.1111/bjd.18227 Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/13652133/182/3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myers A, Kay LJ, Lynch SA, et al. Recurrence risk for psoriasis and Psoriatic arthritis within Sibships. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:773–6. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eder L, Polachek A, Rosen CF, et al. The development of Psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of nonspecific musculoskeletal symptoms: A prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:622–9. 10.1002/art.39973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zabotti A, McGonagle DG, Giovannini I, et al. Transition phase towards Psoriatic arthritis: clinical and ultrasonographic Characterisation of Psoriatic arthralgia. RMD Open 2019;5:e001067. 10.1136/rmdopen-2019-001067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon D, Tascilar K, Kleyer A, et al. Association of structural Entheseal lesions with an increased risk of progression from psoriasis to Psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2022;74:253–62. 10.1002/art.41239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faustini F, Simon D, Oliveira I, et al. Subclinical joint inflammation in patients with psoriasis without concomitant Psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:2068–74. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zabotti A, Tinazzi I, Aydin SZ, et al. From psoriasis to Psoriatic arthritis: insights from imaging on the transition to Psoriatic arthritis and implications for arthritis prevention. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2020;22:24. 10.1007/s11926-020-00891-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scher JU, Ogdie A, Merola JF, et al. Preventing Psoriatic arthritis: focusing on patients with psoriasis at increased risk of transition. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2019;15:153–66. 10.1038/s41584-019-0175-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perez-Chada LM, Haberman RH, Chandran V, et al. Consensus terminology for Preclinical phases of Psoriatic arthritis for use in research studies: results from a Delphi consensus study. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2021;17:238–43. 10.1038/s41584-021-00578-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zabotti A, De Lucia O, Sakellariou G, et al. Predictors, risk factors, and incidence rates of Psoriatic arthritis development in psoriasis patients: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Ther 2021;8:1519–34. 10.1007/s40744-021-00378-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eder L, Haddad A, Rosen CF, et al. The incidence and risk factors for Psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: A prospective cohort study. Arthritis & Rheumatology 2016;68:915–23. 10.1002/art.39494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGonagle DG, Zabotti A, Watad A, et al. Intercepting Psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: buy one get one free? Ann rheum DIS Ann Rheum Dis 2022;81:7–10. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aydin SZ, Bridgewood C, Zabotti A, et al. The transition from Enthesis physiological responses in health to aberrant responses that underpin Spondyloarthritis mechanisms. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2021;33:64–73. 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raza K, Saber TP, Kvien TK, et al. Timing the therapeutic window of opportunity in early rheumatoid arthritis: proposal for definitions of disease duration in clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1921–3. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aletaha D. The undifferentiated arthritis dilemma: the story continues. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2022;18:189–90. 10.1038/s41584-022-00762-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells G, O’Connell D, Peterson J. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of Nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2013. Available: http://wwwohrica/programs/clinical_ epidemiology/oxfordasp

- 22.Abji F, Lee K-A, Pollock RA, et al. Declining levels of serum Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 over time are associated with new onset of Psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a new biomarker. Br J Dermatol 2020;183:920–7. 10.1111/bjd.18940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elnady B, El Shaarawy NK, Dawoud NM, et al. Subclinical Synovitis and Enthesitis in psoriasis patients and controls by Ultrasonography in Saudi Arabia; incidence of Psoriatic arthritis during two years. Clin Rheumatol 2019;38:1627–35. 10.1007/s10067-019-04445-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Acosta Felquer ML, LoGiudice L, Galimberti ML, et al. Treating the skin with Biologics in patients with psoriasis decreases the incidence of Psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2022;81:74–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belman S, Walsh JA, Carroll C, et al. Psoriasis characteristics for the early detection of Psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2021;48:1559–65. 10.3899/jrheum.201123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gisondi P, Bellinato F, Targher G, et al. Biological disease-modifying Antirheumatic drugs may mitigate the risk of Psoriatic arthritis in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. Ann Rheum Dis 2022;81:68–73. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-219961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mulder MLM, van Hal TW, Wenink MH, et al. Clinical, laboratory, and genetic markers for the development or presence of Psoriatic arthritis in psoriasis patients: a systematic review. Arthritis Res Ther 2021;23:168. 10.1186/s13075-021-02545-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiu Y-H. The transition from psoriasis (PS) to Psoriatic arthritis (PSA) is associated with elevated circulating Osteoclast precursors (OCP) and increased expression of DC-STAMP. ACR 2012 meeting Abstracts; [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eder L, Li Q, Jerome D, et al. The performance of a multi-marker genetic test to identify patients with Psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:1160. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-eular.1127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pollock R, Machhar R, Chandran V, et al. Op0203 CHARACTERIZING the Epigenomic landscape of psoriasis patients destined to develop Psoriatic arthritis. Annual European Congress of Rheumatology, EULAR 2019, Madrid, 12–15 June 2019; June 2019:177–8 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.4185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thiele RG. Abnormal imaging and increased Osteoclast precursors in a psoriasis cohort are associated with new onset of Psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2013:S130. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green A, Tillett W, McHugh N, et al. Using Bayesian networks to identify musculoskeletal symptoms influencing the risk of developing Psoriatic arthritis in people with psoriasis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2022;61:581–90. 10.1093/rheumatology/keab310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balato A, Caiazzo G, Balato N, et al. Psoriatic arthritis onset in Psoriatic patients receiving UV Phototherapy in Italy. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2020;155:733–8. 10.23736/S0392-0488.18.06117-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cuervo A, Celis R, Julià A, et al. Synovial Immunohistological biomarkers of the classification of undifferentiated arthritis evolving to rheumatoid or Psoriatic arthritis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021;8:656667. 10.3389/fmed.2021.656667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paalanen K, Rannio K, Rannio T, et al. Does early Seronegative arthritis develop into rheumatoid arthritis? A 10-year observational study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2019;37:37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pérez LE. Evolutionary study of 45 cases of undifferentiated negative HLA B27 Seronegative Oligoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018:1678. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abji F, Lee K-A, Pollock RA, et al. Declining levels of serum Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 over time are associated with new onset of Psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a new biomarker? Br J Dermatol 2020;183:920–7. 10.1111/bjd.18940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D’Angelo S, Mennillo GA, Cutro MS, et al. Sensitivity of the classification of Psoriatic arthritis criteria in early Psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2009;36:368–70. 10.3899/jrheum.080596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2023-003143supp001.pdf (62.3KB, pdf)

rmdopen-2023-003143supp002.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.