Abstract

Rationale and Objective

Ravulizumab and eculizumab have shown efficacy for the treatment of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), but real-world evidence for ravulizumab is limited owing to its more recent approval. This real-world database study examined outcomes for adult patients switching to ravulizumab from eculizumab and patients treated with individual treatments.

Study Design

A retrospective, observational study using the Clarivate Real World Database.

Setting and Population

US health-insurance billing data (January 2012 to March 2021) of patients aged 18 years or older with ≥1 diagnosis relevant to aHUS, ≥1 claim for treatment with eculizumab or ravulizumab, and no evidence of other indicated conditions.

Exposures

Treatment-switch (to ravulizumab after eculizumab), ravulizumab-only, and eculizumab-only cohorts were examined.

Outcomes

Clinical procedures, facility visits, health care costs, and clinical manifestations.

Analytical Approach

Paired-sample statistical testing compared the mean numbers of claims for each group 0-3 months before (preindex period) and 0-3 months and 3-6 months after (postindex period) the index date (point of initiation with a single treatment or treatment switch).

Results

In total, 322 patients met the eligibility criteria at 3-6 months postindex in the treatment-switch (n=65), ravulizumab-only (n=9), and eculizumab-only (n=248) cohorts. The proportions of patients with claims for key clinical procedures continued to be small after treatment switch and were small (0%-11%) across all cohorts at 3-6 months postindex. Inpatient visits were reduced in the postindex period across all cohorts. At 3-6 months after treatment switch, patients reported fewer claims for outpatient, private practice, and home visits and lower median health care costs. The proportions of patients with claims for clinical manifestations of aHUS were generally reduced in the postindex period compared with those of the preindex period.

Limitations

Low patient numbers receiving ravulizumab only.

Conclusions

The health-insurance claims data showed a reduced health care burden for US adult patients after treatment with ravulizumab or eculizumab for treatment of aHUS.

Index Words: Complement C5 inhibitors, atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, real-world evidence, treatment patterns, outcomes

Plain language summary.

Ravulizumab and eculizumab are approved treatments for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS). Despite being thoroughly tested in clinical studies, this research aimed to understand their real-world effects. Anonymous health-insurance records were analyzed to see which patients had received these treatments, hospital services they used, and symptoms of aHUS they presented with. Patients had either started treatment with ravulizumab or eculizumab or had switched from eculizumab to ravulizumab. The results of the study indicate that after starting treatment, patients used less health care resources than before treatment. This may be related to improvements in patients’ aHUS. For patients who switched treatment, these benefits were maintained. This may be because of the less frequent infusions of ravulizumab versus eculizumab.

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is a rare form of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), with an estimated incidence of 0.23-1.9 cases per million individuals annually.1 aHUS is characterized by thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, and kidney failure,2 which may manifest in the presence or absence of a triggering condition.3,4 The disease is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality for affected patients; even in those receiving supportive care, such as plasma exchange or infusion, progression to kidney failure or death occurs in 56% of adult and 29% of pediatric patients within 1 year of aHUS onset.5

The pathophysiology of aHUS is characterized by uncontrolled terminal complement activation leading to inflammation and tissue injury, primarily affecting the kidneys.6 Targeted complement inhibitors represent a therapeutic option in aHUS to prevent inappropriate complement activation. Ravulizumab and eculizumab are terminal complement C5 inhibitors approved for the treatment of aHUS7,8; eculizumab was first approved for aHUS in the United States in 2011, and ravulizumab received initial US approval in 2019.7, 8, 9, 10 The efficacy and favorable safety profile of eculizumab have been shown in both adult and pediatric patients with aHUS in clinical trials11, 12, 13, 14 and the Global aHUS Registry.15 However, its requirement for 2-week dosing intervals for patients weighing 10 kg or more7 can impose a treatment burden on some patients, their caregivers, and the health care system.16,17 Ravulizumab, a long-acting, next-generation terminal complement inhibitor, was designed by targeted modification of eculizumab to enhance antibody recycling and attenuate target-mediated drug disposition to achieve an extended half-life,18 enabling less frequent dosing than with eculizumab. Ravulizumab is administered once every 4-8 weeks, depending on patient body weight, and provides immediate and complete complement C5 inhibition with this dosing.8

Both therapies have shown meaningful clinical benefit, as measured by complete TMA response (improvement in kidney function and normalization of platelets and lactate dehydrogenase),13,19 which is the standard primary end point for clinical trials in patients with aHUS. This end point was met by 56% of adult patients receiving eculizumab (NCT01194973) and 54% of adult patients treated with ravulizumab after 26 weeks (NCT02949128).11,19 A complete TMA response was also achieved in 61% of the adult patients treated with ravulizumab at 52 weeks (NCT02949128).20 In pediatric patients, complete TMA response at 26 weeks was seen in 64% and 78% of the patients treated with eculizumab (NCT01193348) and ravulizumab (NCT03131219), respectively, which rose to 94% of the pediatric patients receiving ravulizumab achieving complete TMA response at 50 weeks (NCT03131219).14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 Furthermore, an indirect comparison of adult patient outcomes at 26 weeks after initiation of eculizumab or ravulizumab treatment in clinical trials detected no significant differences in kidney function, hematological markers, dialysis prevalence, fatigue, or quality-of-life measures between the treatment groups.22 Hence, the safety profile of ravulizumab is comparable with that of eculizumab in adults and pediatric patients.19,21,23

Although the efficacy and safety of both eculizumab and ravulizumab have previously been shown in clinical trials,11, 12, 13, 14,19, 20, 21,23 complementary real-world evidence for ravulizumab is currently lacking. This study assessed US claims data regarding demographic and clinical patient profiles, treatment patterns, clinical procedures, health care resource utilization, and clinical manifestations for US adults with aHUS who switched from eculizumab to ravulizumab or were treated with ravulizumab or eculizumab alone.

Methods

Study Design

This was a retrospective, observational study using US health-insurance billing data from the Clarivate (formerly Decision Resources Group) Real World Database24 from January 2012 to March 2021. This data window included ∼14 months of data after the approval of ravulizumab. The Clarivate Real World Database has held individual-level and facility-level claims data for more than 300 million unique patients since 2011, across various payers and plans, and contains both medical and pharmacy benefit claims.24

Study Population

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they showed: 1) at least 1 medical or pharmacy claim for treatment with eculizumab or ravulizumab; 2) at least 1 medical claim with International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis codes relevant to aHUS; and 3) no evidence of Shiga toxin Escherichia coli-related hemolytic uremic syndrome or other conditions for which ravulizumab or eculizumab are indicated, such as paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, myasthenia gravis, or neuromyelitis optical spectrum disorder in the 3 months before treatment initiation (codes used to define each inclusion and exclusion criterion are summarized in Table S1). Patients were required to be aged 18 years or older at the time of treatment initiation, with ≥3 months of continuous database enrollment before and after treatment initiation. A descriptive analysis of patient demographics and treatment characteristics was performed on the overall population defined by these criteria.

Patients were divided into 3 cohorts, namely, those who switched from eculizumab to ravulizumab (the switch cohort), and those who received ravulizumab only or eculizumab only (the single treatment cohorts). Patients who switched treatments were required to show ≥1 claim for treatment with eculizumab and ≥1 subsequent claim for treatment with ravulizumab (with ≥ 3 months of continued use for both treatments) within the study period, with 7-30 days between the last eculizumab claim and the first ravulizumab claim and no evidence of eculizumab use after the first ravulizumab claim. Patients in the ravulizumab-only cohort were required to present with ≥1 claim for treatment with ravulizumab and no evidence of eculizumab use during the study. Finally, patients in the eculizumab-only cohort were required to exhibit ≥1 claim for treatment with eculizumab within the study period and no evidence of ravulizumab use during the study. Continued use was defined as showing no more than 30 days between eculizumab claims or 63 days between ravulizumab claims.

Study Variables

For patients receiving eculizumab only or ravulizumab only, the index date was defined as the date of the first claim for eculizumab or ravulizumab, respectively. For patients who switched from eculizumab to ravulizumab treatment, the index date was determined to be the date of the first ravulizumab claim, and this was treated as the date of treatment switch. Study variables were compared before and after the index date for each cohort. Variables assessed included patient characteristics (age, sex, payer type, and place of service), treatment patterns, clinical procedures (proportion of patients with claims for dialysis, plasma exchange [PE], kidney transplantation, and red blood cell or platelet transfusion), claims for facility visits and health care costs, and clinical manifestations [proportion of patients with claims for anemia, hemolytic anemia, hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD), kidney failure (formerly known as end-stage renal disease),25 proteinuria, and thrombocytopenia]. For facility visits, not only aHUS-related claims but also any claim with an associated site of care occurring during the study period was included in the analysis. Health care costs were calculated as the sum of payments associated with only aHUS-relevant codes, such as payer costs and patient out-of-pocket rates. The cost data were reported as the actual cost during the study period and were not adjusted for inflation. The costs of eculizumab and ravulizumab were not included in the analysis of health care costs, and only patients with ≥80% of relevant claims linked to settled remittance during each period were included.

Statistical Analysis

All study variables, such as baseline and outcome measures, were analyzed descriptively, and results were stratified by patient cohort. Descriptive statistics (patient counts and percentages) were summarized for age, sex, and payer type; means, medians, ranges, and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables. For analyses of clinical manifestations, clinical procedures, and health care resource utilization over time, patients were required to have ≥6 months of eculizumab or ravulizumab treatment after initiation. For all treatment cohorts, the proportion of patients with claims for clinical manifestations, the proportion of patients with claims for clinical procedures, the mean number of claims per patient for facility visits, and the median health care costs at 0-3 months and 3-6 months postindex were compared with those of 0-3 months preindex. Statistical analyses were performed using McNemar tests, χ2 tests, t tests, and Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank tests to compare the proportion of patients undergoing clinical procedures, the mean number of claims per patient for facility visits, and the health care costs between the preindex and postindex periods, with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Study Population

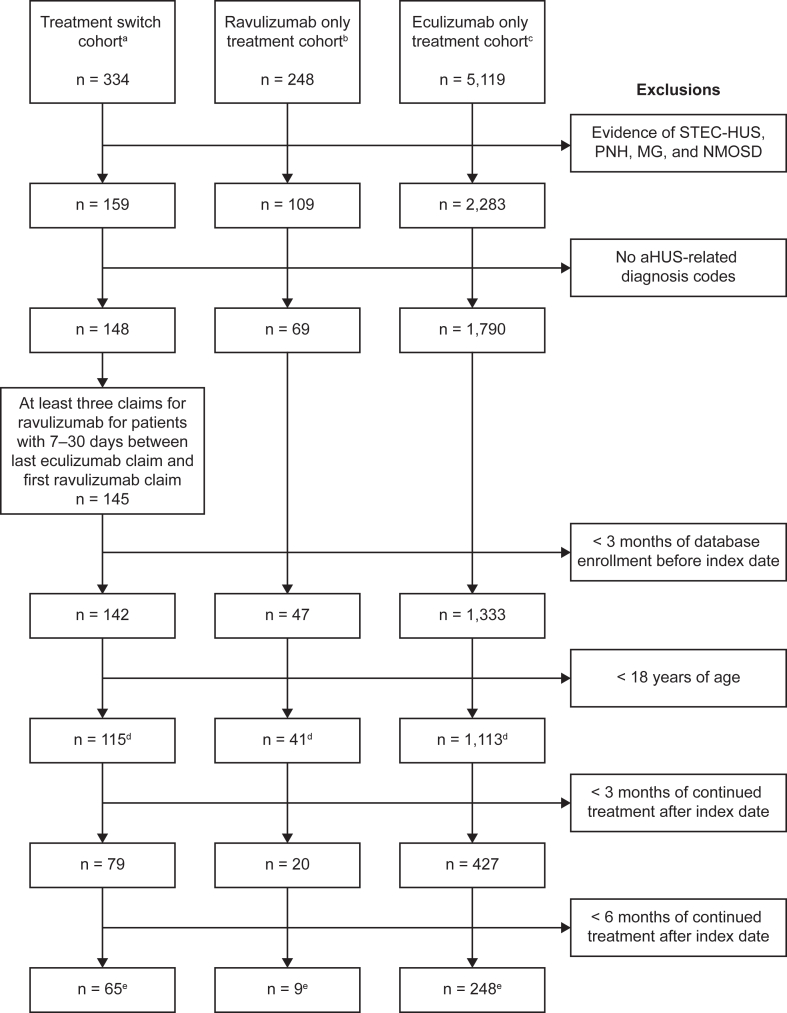

Overall, 1,269 patients met the inclusion criteria across the switch (n=115), ravulizumab-only (n=41), and eculizumab-only (n=1,113) cohorts. At 3 and 6 months postindex, there were 526 and 322 patients meeting the treatment-duration requirements, respectively, who were included in the analysis. Of the 322 patients meeting the eligibility criteria at 3-6 months postindex, 65 were in the switch cohort, 9 were in the ravulizumab-only cohort, and 248 were in the eculizumab-only cohort. Further details of the numbers of patients meeting the eligibility criteria for each cohort are shown in Fig 1.

Figure 1.

Participant disposition and inclusion/exclusion criteria. aHUS, atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome; MG, myasthenia gravis; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optical spectrum disorder; PNH, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; STEC-HUS, Shiga toxin Escherichia coli-related hemolytic uremic syndrome. aThe switch cohort was required to have ≥ 1 claim for treatment with eculizumab and ≥ 1 claim for treatment with ravulizumab afterward within the study period, 7-30 days between the last eculizumab claim and first ravulizumab claim, and no evidence of eculizumab use after first ravulizumab use. bThe ravulizumab-only cohort was required to have ≥ 1 claim for treatment with ravulizumab and no evidence of eculizumab use in the study period. cThe eculizumab-only cohort was required to have ≥ 1 claim for treatment with eculizumab and no evidence of ravulizumab use in the study period. dDefines the sample used for descriptive analysis of patient demographics and treatment characteristics. eRepresents the sample used for analyses of outcomes for the 3-6 months postindex period.

Demographics and Treatment Characteristics

Approximately 30% of patients were aged between 18 and 34 years, which represented the highest proportion among all age groups (Table 1). At the index date, the mean age of patients switching treatment was 42.4 years compared with 46.9 and 46.6 years for patients in the ravulizumab-only and eculizumab-only cohorts, respectively.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Treatment Characteristics for All Patients by Cohort

| Patient Characteristics and Payer Type | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | Switch |

Ravulizumab Only |

Eculizumab Only |

| (n=115) | (n=41) | (n=1,113) | |

| Age, y | |||

| 18-34 | 38 (33) | 11 (27) | 331 (30) |

| 35-44 | 23 (19) | 7 (17) | 174 (16) |

| 45-54 | 16 (14) | 5 (12) | 185 (17) |

| 55-64 | 17 (15) | 9 (22) | 232 (21) |

| 65+ | 21 (18) | 9 (22) | 191 (17) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 74 (64) | 28 (68) | 738 (66) |

| Male | 41 (36) | 13 (32) | 375 (34) |

| Payer type | |||

| Commercial | 73 (63) | 21 (51) | 759 (68) |

| Medicaid | 10 (9) | 10 (24) | 103 (9) |

| Medicare | 22 (19) | 7 (17) | 162 (15) |

| VA/other | 10 (9) | 3 (7) | 89 (8) |

| Point of service | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients With Available Data, n (%) | Switch |

Ravulizumab Only |

Eculizumab Only |

| (n=97) | (n=37) | (n=954) | |

| First aHUS diagnosis | |||

| ER | 10 (10) | 1 (3) | 121 (13) |

| Home | 4 (4) | 1 (3) | 20 (2) |

| Inpatient | 47 (48) | 20 (54) | 491 (51) |

| Other | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 12 (1) |

| Outpatient | 28 (29) | 11 (30) | 222 (23) |

| Private practice | 7 (7) | 4 (11) | 88 (9) |

| Patients With Available Data, n (%) | Switch |

Ravulizumab Only |

Eculizumab Only |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=79) | (n=25) | (n=817) | |

| First aHUS treatment | |||

| ER | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Home | 17 (22) | 2 (8) | 97 (12) |

| Inpatient | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 15 (2) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (< 1) |

| Outpatient | 40 (51) | 15 (60) | 408 (50) |

| Pharmacy | 1 (1) | 1 (4) | 33 (4) |

| Private practice | 20 (25) | 6 (24) | 260 (32) |

Note: Percentages may not add up to 100 owing to rounding. Patients in each cohort were required to have ≥ 3 months of enrollment in the database.

Abbreviations: aHUS, atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome; ER, emergency room; VA, Veterans Affairs.

In total, 66% of the patients across the overall study population were female, with the ratio of patients by sex being relatively similar across cohorts. Most patients had commercial insurance at the index date, and Medicaid and Medicare coverage were comparable across the total patient cohort, accounting for 10% and 15% of patients, respectively. The median age at first aHUS diagnosis was 40 years for patients who switched treatment and 47 years for the single treatment cohorts (patients receiving ravulizumab or eculizumab only). The median age at first eculizumab and ravulizumab treatment for the switch cohort was 41 and 43 years, respectively, and for patients receiving single treatments, the median age at initiation of ravulizumab or eculizumab treatment was 48 years.

On the basis of patients with ≥ 3 months of continued treatment in the postindex period, the number of months of treatment was highly variable, with a median (range) of 9.5 (1.2-15.4) months of eculizumab treatment before the treatment switch. For patients treated with ravulizumab only or eculizumab only, the length of treatment from the point of initiation to the last observed claim for treatment was 3.8 (1.8-13.6) months and 10.8 (2.4-89.9) months, respectively.

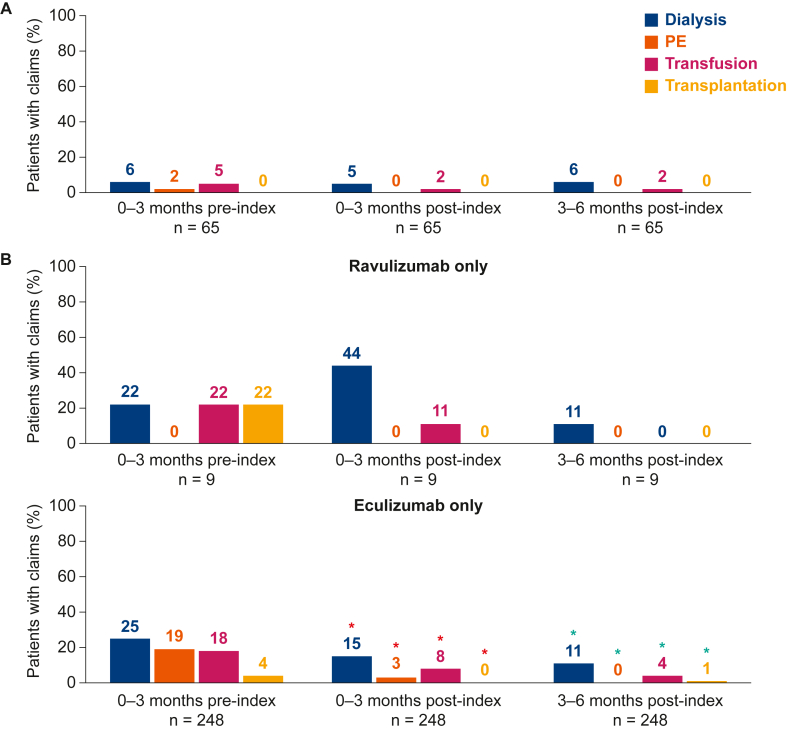

Clinical Procedures

The proportion of treatment-switch patients with claims for each clinical procedure was small (<10%) at all time points, with no claims for PE or kidney transplantation after treatment switch (Fig 2A). For the relatively small cohort of patients receiving ravulizumab only with available data (n=9), few claims were observed for clinical procedures in each period (Fig 2B). At 3-6 months postindex, no patients showed claims for PE, transfusion, or kidney transplantation, and only 1 patient claimed for dialysis in this cohort. For patients treated with eculizumab only (n=248), compared with those during the 0- to 3-month preindex period, the proportions of patients with claims for each clinical procedure were significantly smaller during the 0- to 3-month and 3- to 6-month postindex periods (P < 0.05) (Fig 2B).

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients with claims for clinical procedures before and after the index date for (A) adult patients who switched from eculizumab to ravulizumab treatment, and (B) adult patients receiving treatment with ravulizumab or eculizumab only. aP < 0.05 [only analyzed for 0-3 months preindex vs 0-3 months postindex (red asterisks) and for 0-3 months preindex vs 3-6 months postindex (green asterisks)]. Owing to the small sample size, no inferential statistical analysis is reported for patients receiving ravulizumab only. Outcomes analyses required at least 6 months of continued eculizumab/ravulizumab use after the index date. Transfusion includes red blood cell and platelet transfusions. PE, plasma exchange.

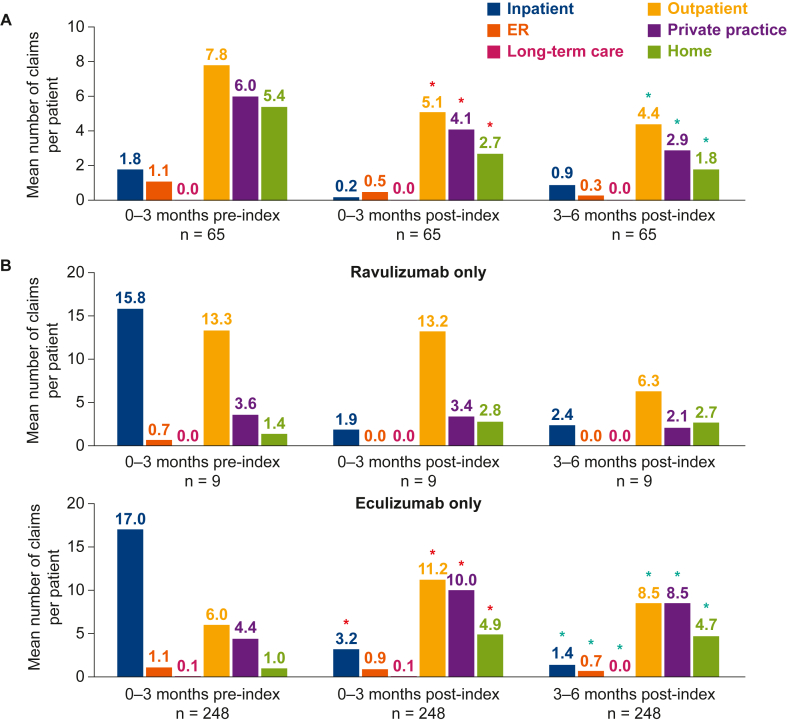

Health Care Facility Visits

For patients who switched treatments, compared with that of the 0- to 3-month preindex period, the average number of claims for inpatient, emergency room, outpatient, private practice, and home visits was lower at 0-3 months and 3-6 months postindex, with no claims relating to long-term care visits reported over the same period (Fig 3A). Inpatient visits for patients treated only with ravulizumab or eculizumab followed the same trend at 0-3 and 3-6 months postindex, with a decrease in the number of inpatient claims compared with that at 0-3 months preindex, although an increase in home visit claims was observed over the same period for patients receiving the single treatments only (Fig 3B). From 0-3 months preindex to 3-6 months postindex, claims for outpatient, private practice, and emergency room visits decreased for patients receiving ravulizumab only, and no claims for visits relating to long-term care were reported. By contrast, claims for visits to outpatient and private practice facilities increased in the eculizumab-only cohort over the same period, whereas emergency room and long-term care visits decreased.

Figure 3.

Mean number of claims for facility visits, before and after the index date, for patients with data available for (A) adult patients who switched from eculizumab to ravulizumab, and (B) adult patients receiving treatment with ravulizumab or eculizumab only. aP < 0.05 [only analyzed for 0-3 months preindex vs 0-3 months postindex (red asterisks), and for 0-3 months preindex vs 3-6 months postindex (green asterisks)]. Owing to the small sample size, no inferential statistical analysis is reported for patients receiving ravulizumab only. Outcomes analyses required at least 6 months of continued eculizumab or ravulizumab use after the index date. The n values vary owing to the number of patients in each time window with data available. Any claim, not just aHUS-related claims, within the 3-month time window with an associated site-of-care variable were included in this analysis. ER, emergency room.

Health Care Costs

The median health care cost (not including costs of ravulizumab or eculizumab) for patients who switched treatment was $1,838 during 0-3 months preindex, decreasing by 6.9% and 49.8% to $1,711 and $923 during 0-3 and 3-6 months postindex, respectively (Fig S1). No patients treated with ravulizumab only met the criteria to be included in this analysis (having paid remit claims linked to ≥80% of their relevant medical claims in each period). For patients treated with eculizumab only, the median health care costs were $2,064 in the 0- to 3-month preindex period, increasing by 53.5% and 30.0% to $3,169 and $2,684 in the 0- to 3-month and 3- to 6-month postindex periods, respectively.

Clinical Manifestations

In the 0- to 3-month preindex period, the proportions of treatment-switch patients who reported claims for clinical manifestations of interest were generally low, likely owing to treatment with eculizumab during this period. These data and the levels of clinical manifestation claims in the 0- to 3-month preindex period for the single treatment cohorts (who were not receiving C5 inhibitor therapy during this period) are shown in Table 2. The percentage of patients with clinical manifestation claims of interest was generally reduced across most manifestations in the 0- to 3-month postindex period compared with that in the 0- to 3-month preindex period in both the switch cohort and the single treatment cohorts, with reductions generally sustained or improved in the 3- to 6-month postindex period (Table 2). The proportion of treatment-switch patients in the 0- to 3-month preindex period with claims for hypertension, CKD, and kidney failure decreased from 42%, 38%, and 35% to 32%, 28%, and 25%, respectively, in the 3- to 6-month postindex period. Less than 10% of treatment-switch patients reported claims for thrombocytopenia or hemolytic anemia at any time point, and the proportions of patients with claims for these clinical manifestations remained similar over the 0- to 3-months preindex period to the 3- to 6-month postindex period. The proportions of patients receiving ravulizumab only with claims for some clinical manifestations reduced over the same period, but this was based on only a small number of patients with available data (n=9). For patients receiving eculizumab only, from 0-3 months preindex to 3-6 months postindex, reductions in the proportions of patients with claims for anemia (49%-31%), hypertension (53%-41%), thrombocytopenia (25%-13%), and kidney failure (48%-30%) were also observed, whereas no difference was observed in the proportion of these patients with claims for CKD.

Table 2.

Number and Proportion of Patients with Claims for Clinical Manifestations of aHUS from 0 to 3 Months Preindex to 6 Months Postindex by Cohort

| Clinical Manifestation | Switch |

Ravulizumab Only |

Eculizumab Only |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=65) | (n=9) | (n=248) | |

| Anemia, n (%) | |||

| 0-3 mo preindex | 12 (18) | 3 (33) | 122 (49) |

| 0-3 mo postindex | 9 (14) | 3 (33) | 100 (40) |

| 3-6 mo postindex | 9 (14) | 1 (11) | 76 (31) |

| Hemolytic anemia, n (%) | |||

| 0-3 mo preindex | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 37 (15) |

| 0-3 mo postindex | 4 (6) | 2 (22) | 27 (11) |

| 3-6 mo postindex | 3 (5) | 1 (11) | 16 (6) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | |||

| 0-3 mo preindex | 27 (42) | 7 (78) | 131 (53) |

| 0-3 mo postindex | 18 (28) | 5 (56) | 124 (50) |

| 3-6 mo postindex | 21 (32) | 5 (56) | 101 (41) |

| Proteinuria, n (%) | |||

| 0-3 mo preindex | 4 (6) | 2 (22) | 24 (10) |

| 0-3 mo postindex | 3 (5) | 2 (22) | 18 (7) |

| 3-6 mo postindex | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 13 (5) |

| Thrombocytopenia, n (%) | |||

| 0-3 mo preindex | 6 (9) | 3 (33) | 62 (25) |

| 0-3 mo postindex | 2 (3) | 3 (33) | 38 (15) |

| 3-6 mo postindex | 6 (9) | 1 (11) | 33 (13) |

| CKD, n (%) | |||

| 0-3 mo preindex | 25 (38) | 6 (67) | 102 (41) |

| 0-3 mo postindex | 20 (31) | 5 (56) | 110 (44) |

| 3-6 mo postindex | 18 (28) | 4 (44) | 104 (42) |

| Kidney failurea, n (%) | |||

| 0-3 mo preindex | 23 (35) | 7 (78) | 118 (48) |

| 0-3 mo postindex | 17 (26) | 8 (89) | 103 (42) |

| 3-6 mo postindex | 16 (25) | 7 (78) | 74 (30) |

Note: For the treatment-switch patients, those receiving ravulizumab only, and those receiving eculizumab only, a total of 65, 9, and 248 patients in these cohorts, respectively, had data available from 3 months preindex to 6 months postindex.

Abbreviations: aHUS, atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Kidney failure was formerly known as end-stage renal disease.

Discussion

This retrospective claim study is the first, to our knowledge, to examine real-world data on health care resource utilization and claims for clinical manifestations of aHUS in a relatively large cohort of US adults with aHUS who switched from eculizumab to ravulizumab and those treated with ravulizumab alone. These data thereby provide a valuable contribution to the understanding of real-world treatment patterns for ravulizumab, given that the real-world evidence for ravulizumab is currently limited to case reports and case series.26, 27, 28, 29, 30 In this study, there were few treatment-switch patients with claims for aHUS-related clinical procedures at all time points, potentially because of disease stabilization during the eculizumab treatment before switching the treatment to ravulizumab, and there were fewer health care facility and home visits and lower medical costs during the postindex versus the preindex period. In addition, fewer patients who switched treatment reported claims for clinical manifestations over the postindex versus preindex period. Reductions in claims for clinical manifestations during ravulizumab treatment in patients switching from eculizumab were generally maintained for ≤6 months after index date, and there were no increases in the proportions of patients with claims for clinical manifestations compared with those in the preindex period of eculizumab treatment. Again, this may be because of stabilization of patient hematological parameters during eculizumab treatment before switching to ravulizumab; for example, there was a reduction in claims for kidney failure after treatment initiation for patients treated with eculizumab only, as would be expected. The proportion of treatment-switch patients with claims for kidney failure also decreased during ravulizumab treatment, in addition to any reduction during preindex eculizumab treatment. In the case of CKD, which remained stable for patients initiated on eculizumab only, the proportion of treatment-switch patients with claims for CKD reduced by 10% at 3-6 months after index date. The postindex period reductions in claims for clinical manifestations and procedures were also seen through 6 months postindex for patients receiving ravulizumab only. However, the findings for this cohort were based on a small number of patients with available data, which limited the ability to perform an inferential statistical analysis.

Although the efficacy of ravulizumab has already been shown,19, 20, 21,23,31 this study adds to a growing body of evidence showing the potential benefits of ravulizumab treatment for patients with aHUS. This includes economic modeling studies that have shown that patients treated with ravulizumab exhibit reduced lost productivity costs related to treatment16 and reduced treatment-associated costs, when compared with patients receiving eculizumab treatment.16,17 Consistent with these findings, this analysis showed that health care costs excluding the cost of ravulizumab and eculizumab were meaningfully reduced after the treatment switch, potentially owing to the less frequent administration of ravulizumab than that of eculizumab. In a previous research, it was estimated that the undiscounted average annualized cost of ravulizumab 10 mg/mL over a lifetime for an adult, including costs of work productivity loss because of treatment, was $436,810, a 32.7% reduction versus eculizumab, at $649,007.16 The corresponding cost for ravulizumab 100 mg/mL was $436,049.16 The evaluation of the costs of these drugs was excluded from this analysis to enable a comparison of other health care costs without masking any potential effect with the difference in cost between the treatments described by previous research using cost minimization models.16,17 The clinical profiles of patients, as indicated by claims for clinical manifestations, showed improvements or were consistent over time, and facility visits were also observed to decrease after the treatment switch, potentially owing to the longer dosing interval of ravulizumab than that of eculizumab, which may have led to fewer visits. Furthermore, a previously published discrete-choice experiment showed that a general population sample preferred ravulizumab dosing regimens over those of eculizumab; in particular, a dosing regimen corresponding to the 100-mg/mL ravulizumab formulation,32 which confers additional benefits of decreased infusion time and number of vials.33 Finally, the comparable efficacy of ravulizumab with that of eculizumab shown in an indirect trial comparison and meta-analysis of patients with aHUS22,34 provides important evidence when considering ravulizumab as a treatment option in countries or regions where it has been approved.8,35,36

In contrast to ravulizumab, which received a more recent approval date for aHUS than eculizumab in the United States (2019 vs 2011, respectively),7, 8, 9, 10 there is enormous real-world evidence available for eculizumab in patients with aHUS. A particularly important source for such data has been the Global aHUS Registry, data from which have reported positive effects for eculizumab regarding patient-reported outcomes37 and in managing aHUS triggered by pregnancy.38 Furthermore, previous analyses of US claims databases have indicated lower hospitalization costs and use of supportive therapies (dialysis and PE) in patients who initiate eculizumab relatively early39 and decreased use of supportive therapies over time in patients treated with eculizumab.40 The results of this study were generally aligned with the existing real-world data for eculizumab. Patients treated solely with eculizumab showed reductions in claims for hemolytic anemia, kidney failure, and thrombocytopenia after eculizumab initiation. Moreover, although claims for both transfusion and transplantation were still reported by patients treated with eculizumab only at 3-6 months postindex, the percentage of patients who reported claims for these procedures reduced from 18% to 4% for blood or platelet transfusion and from 4% to 1% for patients requiring kidney transplantation in the 3-6 months postindex compared with 0-3 months preindex, respectively. The relatively large number of patients receiving eculizumab with available data enabled a better assessment of changes between time points than for the cohort receiving ravulizumab only. As more patients receive ravulizumab over time, future studies may be performed with larger cohorts of patients receiving this treatment with longer follow-ups, as have previously been conducted for patients receiving eculizumab. The Global aHUS Registry is currently enrolling patients treated with ravulizumab, with data collection under way at the time of writing (NCT01522183).

Across all 3 cohorts, there were several other notable differences. First, there were slight differences in patient characteristics across the 3 treatment cohorts, with patients who switched treatment being generally younger, suggesting that younger patients may be more willing to try new treatments; other factors such as genetics, family history, recurrence of thrombotic microangiopathy, and physician recommendations or decisions regarding treatment may also play a role. Owing to eculizumab treatment in the preindex period, patients who switched treatments also reported a lower baseline level of claims for clinical manifestations of aHUS than those in the cohorts receiving eculizumab or ravulizumab only.

The strengths and limitations of this study must be considered. The study presents results over the 3- to 6-month postindex period for patients switching therapy or receiving single treatments only, which helps to overcome channeling bias.41 However, owing to the rarity of aHUS1 and the relatively recent approval of ravulizumab,8 there were smaller numbers of patients in the ravulizumab-only and treatment-switch cohorts, compared with the eculizumab-only cohort, limiting the ability to detect statistically significant effects in these patients. Hence, for some analyses, it was only possible to comment on nonsignificant trends. The requirement for participants to have ≥6 months of treatment with ravulizumab (as recommended in the prescribing information)8 or eculizumab postindex was an attempt to ensure that the study variables were only analyzed for patients known to be undergoing treatment. The limitation of this approach is that it may introduce a selection bias because of the exclusion of patients who initiated but ceased treatment or those lost to follow-up. Patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) could not be directly excluded from this study owing to the absence of a distinct diagnostic code for TTP and the lack of disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13 (ADAMTS13) test data in the claims database. However, the requirement for patients to have ≥1 claim for eculizumab or ravulizumab treatment makes it unlikely that patients with TTP were included. There were differences in the median length of time on treatment between the cohorts for patients with ≥3 months of treatment in postindex, which may have been affected by the greater length of time since eculizumab approval for the treatment of aHUS versus ravulizumab; as an example, the greater duration of eculizumab availability versus ravulizumab availability may mean that eculizumab was part of the formulary for some hospitals and, hence, may be supplied more readily to appropriate patients. Limitations associated with the claims data also require consideration because health-insurance claims data inherently carry the potential for miscoded or incomplete claims, with only ∼30% of claims having associated with cost data in this study. In addition, claims data lack information on laboratory results, genetic testing, and other comorbidities that would help to interpret the clinical outcomes and health care resource utilization. Therefore, although the patterns in claims of clinical manifestations provide some indication of the outcomes for these patients, caution should be taken in linking these findings to treatment effectiveness.

In conclusion, although limited data were available for patients treated with ravulizumab only, when taken together with the findings from patients switching to ravulizumab, this study points to a reduction in health care burden for adult patients with aHUS receiving ravulizumab therapy and suggests a sustained benefit in patients who switched treatments. Subsequent studies with an increased number of patients who have switched from eculizumab to ravulizumab or who are receiving ravulizumab only will be needed to validate and support our main novel findings, and further analyses using pediatric data would be beneficial to understand better the real-world usage of complement C5 inhibitors across overall patient populations with aHUS in the United States.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Yan Wang, PhD, Imad Al-Dakkak, DMD MPH, Katherine Garlo, MD, Moh-Lim Ong, MD, Ioannis Tomazos, PhD, Arash Mahajerin, MD.

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea and study design: YW, IT, AM; data analysis/interpretation: YW, IA-D, KG, M-LO, IT, AM; supervision and mentorship: YW, IT. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

This study was sponsored and funded by Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Boston, MA, USA. Authors YW, IA-D, KG, M-LO, and IT are/were employees of Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, and were involved in the study design, data collection, analysis, and reporting, and provided final approval to submit for publication. Medical writing support was provided by Luke Bratton, PhD, of Oxford PharmaGenesis, Oxford, United Kingdom, and was funded by Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Boston, MA.

Financial Disclosure

Dr Wang, Dr Al-Dakkak, Dr Garlo, and Dr Ong are employees of Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease and own stock/options in Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease. At the time of the study, Dr Tomazos was an employee of Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease and owned stock/options in Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease. He is now an employee of PTC Therapeutics Inc. Dr Mahajerin acted as a consultant to Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease for this study.

Data Sharing

Patient-level data used in this study were obtained on a contractual basis from Clarivate. The study analysis plan was limited to results presented in this article. The data sets generated are not publicly available owing to their proprietary nature.

Peer Review

Received October 24, 2022. Evaluated by 2 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input from the Statistical Editor, an Associate Editor, and the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form April 25, 2023.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

Figure S1. Total median health care costs (excluding eculizumab/ravulizumab prescriptions) before and after the index date for adult patients who switched from eculizumab to ravulizumab or adult patients receiving eculizumab.

Table S1. Diagnostic Codes for Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

Supplementary Material

Fig S1; Table S1.

References

- 1.Yan K., Desai K., Gullapalli L., Druyts E., Balijepalli C. Epidemiology of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: a systematic literature review. Clin Epidemiol. 2020;12:295–305. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S245642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campistol J.M., Arias M., Ariceta G., et al. An update for atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. A consensus document. Nefrologia. 2015;35(5):421–447. doi: 10.1016/j.nefro.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caprioli J., Noris M., Brioschi S., et al. Genetics of HUS: the impact of MCP, CFH, and IF mutations on clinical presentation, response to treatment, and outcome. Blood. 2006;108(4):1267–1279. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-007252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kavanagh D., Goodship T.H., Richards A. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Semin Nephrol. 2013;33(6):508–530. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fremeaux-Bacchi V., Fakhouri F., Garnier A., et al. Genetics and outcome of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: a nationwide French series comparing children and adults. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(4):554–562. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04760512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loirat C., Frémeaux-Bacchi V. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:60. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-6-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.SOLIRIS (eculizumab) injection, for intravenous use. Highlights of prescribing information. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/125166s431lbl.pdf

- 8.ULTOMIRIS (ravulizumab-cwvz) injection, for intravenous use. Highlights of prescribing information. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/761108s023lbl.pdf

- 9.Approval of Soliris (eculizumab) for the treatment of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS). US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/bla/2011/125166Orig1s172-2.pdf

- 10.Approval of Ultomiris (ravulizumab-cwvz) for the treatment of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS). US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2019/761108Orig1s001ltr.pdf

- 11.Fakhouri F., Hourmant M., Campistol J.M., et al. Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in adult patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: a single-arm, open-label trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(1):84–93. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Licht C., Greenbaum L.A., Muus P., et al. Efficacy and safety of eculizumab in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome from 2-year extensions of phase 2 studies. Kidney Int. 2015;87(5):1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Legendre C.M., Licht C., Muus P., et al. Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2169–2181. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenbaum L.A., Fila M., Ardissino G., et al. Eculizumab is a safe and effective treatment in pediatric patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Kidney Int. 2016;89(3):701–711. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2015.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rondeau E., Cataland S.R., Al-Dakkak I., Miller B., Webb N.J.A., Landau D. Eculizumab safety: five-year experience from the global atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome registry. Kidney Int Rep. 2019;4(11):1568–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2019.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy A.R., Chen P., Johnston K., Wang Y., Popoff E., Tomazos I. Quantifying the economic effects of ravulizumab versus eculizumab treatment in patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Med Econ. 2022;25(1):249–259. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2022.2027706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y., Johnston K., Popoff E., et al. A US cost-minimization model comparing ravulizumab versus eculizumab for the treatment of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Med Econ. 2020;23(12):1503–1515. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2020.1831519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheridan D., Yu Z.X., Zhang Y., et al. Design and preclinical characterization of ALXN1210: a novel anti-C5 antibody with extended duration of action. PLoS One. 2018;13(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rondeau E., Scully M., Ariceta G., et al. The long-acting C5 inhibitor, ravulizumab, is effective and safe in adult patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome naive to complement inhibitor treatment. Kidney Int. 2020;97(6):1287–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbour T., Scully M., Ariceta G., et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of the long-acting complement C5 inhibitor ravulizumab for the treatment of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome in adults. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6(6):1603–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.03.884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ariceta G., Dixon B.P., Kim S.H., et al. The long-acting C5 inhibitor, ravulizumab, is effective and safe in pediatric patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome naive to complement inhibitor treatment. Kidney Int. 2021;100(1):225–237. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomazos I., Hatswell A.J., Cataland S., et al. Comparative efficacy of ravulizumab and eculizumab in the treatment of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: an indirect comparison using clinical trial data. Clin Nephrol. 2022;97(5):261–272. doi: 10.5414/CN110516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka K., Adams B., Aris A.M., et al. The long-acting C5 inhibitor, ravulizumab, is efficacious and safe in pediatric patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome previously treated with eculizumab. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36(4):889–898. doi: 10.1007/s00467-020-04774-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Real world data. Clarivate. https://clarivate.com/products/real-world-data/

- 25.Levey A.S., Eckardt K.-U., Dorman N.M., et al. Nomenclature for kidney function and disease: report of a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Consensus Conference. Kidney Int. 2020;97(6):1117–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ehren R., Habbig S. Real-world data of six patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome switched to ravulizumab. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36(10):3281–3282. doi: 10.1007/s00467-021-05203-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu X., Szarzanowicz A., Garba A., Schaefer B., Waz W.R. Blockade of the terminal complement cascade using ravulizumab in a pediatric patient with anti-complement factor H autoantibody-associated aHUS: a case report and literature review. Cureus. 2021;13(11) doi: 10.7759/cureus.19476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt T., Gödel M., Mahmud M., et al. Ravulizumab in preemptive living donor kidney transplantation in hereditary atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Transplant Direct. 2022;8(2):e1289. doi: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000001289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gill J., Hebert C.A., Colbert G.B. COVID-19-associated atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and use of eculizumab therapy. J Nephrol. 2022;35(1):317–321. doi: 10.1007/s40620-021-01125-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jehn U., Altuner U., Pavenstädt H., Reuter S. First report on successful conversion of long-term treatment of recurrent atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome with eculizumab to ravulizumab in a renal transplant patient. Transpl Int. 2022;35 doi: 10.3389/ti.2022.10846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Syed Y.Y. Ravulizumab: a review in atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Drugs. 2021;81(5):587–594. doi: 10.1007/s40265-021-01481-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams K., Aggio D., Chen P., Anokhina K., Lloyd A.J., Wang Y. Utility values associated with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome-related attributes: a discrete choice experiment in five countries. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(8):901–912. doi: 10.1007/s40273-021-01059-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dixon B.P., Sabus A. Ravulizumab 100 mg/mL formulation reduces infusion time and frequency, improving the patient and caregiver experience in the treatment of atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2022;47(7):1081–1087. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.13642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernuy-Guevara C., Chehade H., Muller Y.D., et al. The inhibition of complement system in formal and emerging indications: results from parallel one-stage pairwise and network meta-analyses of clinical trials and real-life data studies. Biomedicines. 2020;8(9):355. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines8090355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ULTOMIRIS (ravulizumab) Summary of product characteristics. EMEA/H/C/004954. European Medicines Agency. https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/product-information/ultomiris-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- 36.ULTOMIRIS (ravulizumab) receives approval in Japan for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) in adults and children. Alexion. Press release, September 25, 2020. https://media.alexion.com/news-releases/news-release-details/ultomirisr-ravulizumab-receives-approval-japan-atypical

- 37.Greenbaum L.A., Licht C., Nikolaou V., et al. Functional assessment of fatigue and other patient-reported outcomes in patients enrolled in the global aHUS registry. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(8):1161–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fakhouri F., Scully M., Ardissino G., Al-Dakkak I., Miller B., Rondeau E. Pregnancy-triggered atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS): a Global aHUS Registry analysis. J Nephrol. 2021;34(5):1581–1590. doi: 10.1007/s40620-021-01025-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan M., Donato B.M.K., Irish W., Gasteyger C., L'Italien G., Laurence J. Economic impact of early-in-hospital diagnosis and initiation of eculizumab in atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38(3):307–313. doi: 10.1007/s40273-019-00862-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomazos I., Levy A., Faria C. PRO77 Preliminary characterization of eculizumab treatment patterns, preceding disease triggers and supportive therapies in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: a US claims database analysis. Value Health. 2021;24(suppl 1):S212. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petri H., Urquhart J. Channeling bias in the interpretation of drug effects. Stat Med. 1991;10(4):577–581. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780100409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1; Table S1.