Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to assess how fatigue is related to mood among youth with sickle cell disease (SCD) by evaluating if the cognitive appraisal of stress moderates the impact of fatigue on emotional functioning consistent with the Risk-and-Resistance Model of Chronic Illness.

Methods

Daily diaries assessing fatigue (Numerical Rating Scale), pain intensity (Numerical Rating Scale), mood (Positive and Negative Affect Schedule for Children), and cognitive appraisal of stress (Stress Appraisal Measure for Adolescents) were collected from 25 youth with SCD (ages 11–18 years) for 8 consecutive weeks resulting in 644 daily diaries for analyses.

Results

When measured concurrently, higher fatigue was associated with higher negative mood controlling for pain and prior-night sleep quality. Fatigue predicted next-day negative mood through its interaction with primary and secondary appraisal of stress, consistent with stress appraisal as a protective factor. A similar pattern was observed for pain, which, like fatigue, is a common SCD-related stressor.

Conclusion

Fatigue and negative mood are inter-related when concurrently assessed, but their temporal association in SCD suggests that mood changes are not an inevitable sequalae of increased fatigue; fatigue influenced subsequent levels of negative mood, but only in the presence of less adaptive cognitions about stress; specifically, a higher perceived threat from stress and a lower belief in the ability to manage stress. The results suggest specific cognitive targets for reducing the negative impact of fatigue on mood in SCD.

Keywords: affect, chronic illness, fatigue, stress appraisal

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic blood disorder that causes physical morbidity (e.g., pain, fatigue) and negatively impacts quality of life, including psychosocial wellbeing (Panepinto & Bonner, 2012). Much of the published research on one aspect of psychosocial wellbeing in SCD, emotional functioning, has focused on how the frequency of pain is related to a co-occurrence of emotional symptoms of depression and anxiety (Reader, Keeler et al., 2020; Reader, Rockman et al., 2020). These data are consistent with other pediatric populations who show a high co-occurrence of pain and depressive symptoms (Soltani et al., 2019). Although youth with SCD may not have persistent internalizing symptoms at a higher rate than peers (Heitzer et al., 2022), transient mood symptoms are likely, given the frequency of medical complications such as pain. Studies have identified fatigue as an additional important type of morbidity in SCD that occurs more often than pain but has received less attention in research and clinical care (Ameringer & Smith, 2011; While & Mullen, 2004). The current study was designed to add to our understanding of fatigue and emotional functioning in SCD by assessing their concurrent and temporal association through the use of daily diary methods. In addition, we evaluated if stress appraisal, a cognitive factor related to stress coping, interacted with fatigue to influence later emotional functioning consistent with the Risk-and-Resistance Model of Chronic Illness (Barakat et al., 2006; Wallander & Thompson, 1995).

SCD is a group of autosomal recessive blood disorders affecting approximately 1 in every 365 African American births in the United States (Hassell, 2010). This disorder affects globin in red blood cells through which S-type cells become rigid and sickled in shape, carry less oxygen, and their altered characteristics contribute to vaso-occlusion in the microvascular supply (Driscoll, 2007; Wills, 2013). Individuals affected by SCD face a range of potential medical complications, including pain crises, anemia with accompanying fatigue, cerebrovascular complications, acute chest syndrome, immune compromise, and organ failure, with increase in incidence with older age (Ballas et al., 2010; Rees et al., 2010). Symptoms of depression and anxiety are among the most common psychological problems among youth with SCD with a combined estimate of clinically meaningful symptoms ranging from 30% to 46% (Hijmans et al., 2009; Jerrell et al., 2011; Thompson et al., 2003). In addition to internalizing symptoms, positive and negative mood states and difficulties regulating day-to-day emotions have been shown to influence decisions about whether to initiate health care for physical symptoms of SCD independent of severity of the physical symptoms (Gil et al., 2003; Tsao et al., 2014). Thus, although similarly high rates of internalizing symptoms may be present in the general adolescent population (Merikangas et al., 2010), emotional functioning may have specific implications for health management for youth with SCD. The associations between physical symptoms of SCD and emotional functioning are not straightforward. For example, simple associations between pain frequency and emotional functioning, or broader disease severity and internalizing symptoms, have typically been modest (Reader, Keeler et al., 2020; Reader, Rockman et al., 2020; Schlenz et al., 2016; Valrie et al., 2020). Thus, more complex models are needed to understand their interrelationship.

Consistent with a biopsychosocial framework, the psychosocial adjustment of children and adolescents with SCD is affected by the interplay of medical complications, disease management, individual characteristics, and social factors (Barakat et al., 2006; Ekinci et al., 2012; Hijmans et al., 2009). The Risk-and-Resistance Model (Wallander & Thompson, 1995) captures these interactions and frames a comprehensive approach to understanding adaptation to chronic illness. This model was developed to understand psychosocial adjustment in children with chronic health conditions and adapted by Barakat et al. (2006) for use with youth with SCD. This Risk-and-Resistance Model incorporates disease- and non-disease-related stressors as risk factors, including medical stressors (e.g., pain, fatigue, neurocognitive deficits), functional independence, and psychosocial disability-related stressors. Resistance factors include stress appraisal, intrapersonal characteristics, and social-ecological components. Resistance factors for youth with SCD have been identified as including competence, self-esteem/self-concept, family environment, social support, caregiver adjustment, child cognitive appraisals, and child coping strategies (Barakat et al., 2006). Whereas risk factors are thought to influence adjustment directly, resistance factors are conceptualized as moderators and mediators of outcomes (Barakat et al., 2006).

In the current study, we use the Risk-and-Resistance Model to examine fatigue as an SCD stressor, which may impact emotional functioning (as a facet of child adaptation in the model). Fatigue is characterized by a subjective feeling of overwhelming tiredness, lack of energy, and exhaustion (Crichton et al., 2015; Levine & Greenwald, 2009). Fatigue in SCD is associated with less engagement in daily activities, less social engagement, lower quality of life, and lower psychological wellbeing (Ameringer et al., 2014; Ameringer & Smith, 2011; While & Mullen, 2004). Fatigue in SCD can be primary, resulting from the disease complications such as anemia, hypoxemia, and chronic inflammation (Ameringer & Smith, 2011; Crichton et al., 2015). The cross-sectional association of fatigue with internalizing symptoms has been conceptualized as being due to higher levels of primary fatigue causing more internalizing symptoms, consistent with fatigue as an SCD stressor in the Risk-and-Resistance Model (Ameringer et al., 2014). Fatigue can also be secondary, resulting from variables such as pain, stress, sleep problems, and mood changes (Ameringer et al., 2014). Consistent with secondary fatigue, we have previously shown that higher negative affect (NA) is associated with increases in next-day fatigue, though the effect size for this temporal association was relatively small (Johnston et al., 2022).

Thus, the relationship between fatigue and emotional functioning may be conceptually complex. Specifically, fatigue is considered to be a secondary symptom of the internalizing disorders, but anxious and depressed mood can also be secondary symptoms triggered by fatigue (Ameringer et al., 2014). This ambiguity between primary and secondary symptoms warrants a prospective examination of the interplay between fatigue and mood (Ameringer et al., 2014). Additional data suggest that fatigue is associated with worse executive functioning among children with SCD, which could challenge cognitive coping resources and weaken these resistance factors (Anderson et al., 2015). More work is needed to determine the temporal precedence of fatigue and emotional functioning and the mechanisms driving the relationship as a guide to understanding the most likely intervention targets to improve child adaptation.

For the current work, we incorporated cognitive stress appraisal from the Risk-and-Resistance Model as a potential moderating factor that could help explain the impact of primary fatigue on mood in youth with SCD. Cognitive appraisal of stress, as defined by Lazarus and Folkman (1984), is a process by which an individual evaluates a potential stressor’s significance to their wellbeing. This model posits that a person’s appraisal or experience of stressors is more integral to understanding their stress rather than an objective assessment of stressor salience (Carver & Vargas, 2011). Cognitive appraisal of stress includes a primary appraisal of how threatening a situation is assessed to be and a secondary appraisal of one’s ability to manage or cope with a perceived stressor (Carpenter, 2016). The cognitive appraisal of stress has both trait and state qualities, with prior studies in individuals without a chronic health condition showing day-to-day variability in cognitive appraisals is associated with the degree of stress hormone response and the degree of positive affect (PA) and NA experienced in response to stressors (Finkelstein-Fox et al., 2019; Gartland et al., 2014).

Currently, mixed findings characterize the relationship between cognitive appraisal of stress and internalizing symptoms in youth with SCD. For example, youth with SCD that rated themselves high on behavioral inhibition (i.e., reacting with fear/withdrawal in unfamiliar situations resulting from a negative appraisal) had increased anxiety and depression (Carpentier et al., 2009), whereas those with hopeful appraisals demonstrated more adaptive behaviors (Ziadni et al., 2011). These findings suggest that stress appraisal may play an important role in psychosocial adjustment. However, in a study using the Risk-and-Resistance Model and examining stress appraisal as a mediator among youths with SCD, cognitive appraisals of stress did not mediate the relationship between intrapersonal characteristics and internalizing symptoms (Simon et al., 2009). Collectively, these data support that stress-processing variables are important to psychosocial adaptation, but their specific role is unclear. Of note, cognitive appraisal of stress has often been measured in this research through retrospective report. Daily measures of stress appraisal are expected to better capture its potential role in influencing mood.

In summary, problems with emotional functioning are common and significant problems for adolescents with SCD (Benton et al., 2007; Ekinci et al., 2012; Jerrell et al., 2011). The association of fatigue with emotional functioning has been established, but the temporal association among these variables is unclear. This study examines how day-to-day changes in fatigue level are related to mood and whether daily changes in stress appraisal will moderate the relationship between fatigue and emotional functioning among youth with SCD. Higher fatigue is expected to be associated with higher same-day negative mood and lower same-day positive mood consistent with prior cross-sectional studies (Hypothesis 1). The cognitive appraisal of stress is expected to moderate the relationship between fatigue and subsequent positive/negative mood, with less adaptive cognitive coping increasing the effect of fatigue on next-day mood (Hypothesis 2). Supplementary Figure 1 provides a visual representation of how Hypothesis 2 fits within relevant portions of the Risk-and-Resistance Model.

Methods

Participants

Thirty-two youths with SCD and a primary caregiver were recruited from a hematology/oncology clinic at a children’s hospital in the southeastern United States as part of the primary author’s dissertation requirements (Reinman, 2019). Participants were youth with SCD ages 11–18 years with daily access to a computer, tablet or smartphone, and English proficiency. Children with major developmental disorders (i.e., intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder), neurologic disease (i.e., overt stroke, moyamoya disease), or currently receiving chronic transfusion therapy were excluded due to the potential impact on the validity of self-report data and/or being medically fragile. Youth reporting pain on the day of recruitment were eligible for consent/assent but completed baseline measures at a later appointment.

Recruitment occurred in two waves: September 2017–April 2018 and September 2018–February 2019. Ninety-one youth who were eligible based on age and medical history attended routine sickle cell preventative care visits during these periods. Parents of 49 of these youth were approached for recruitment with 37 parent–youth dyads expressing interest in participation (32 were enrolled and completed baseline measures, 5 potential participants requested to schedule consent and baseline measures at a later point in time but did not respond to multiple follow-up phone or e-mail contacts or return to the clinic before the study recruitment period ended). Twelve potential participants declined due to lack of interest, most often describing lack of time/competing demands as the reason for declining. For the remaining 42 participants, 4 arrived at appointments extremely late and research staff were no longer in the clinic and 38 were missed due to time conflicts for research staff (e.g., staff already meeting with or running another participant).

Procedures

The study procedure was approved by the hospital IRB. A primary caregiver provided informed consent and youth provided informed assent, after which dyads completed baseline measures in private space within the clinic. Youth and caregivers approached at their clinic appointment could choose to complete baseline measures at that time or to schedule a future appointment. Caregivers of youth endorsing critical items (e.g., thoughts of self-harm) and/or clinical levels of depression or anxiety (and the youth) were provided mental health consultation and referral information for mental health providers.

After completing baseline measures, youth completed electronic daily diaries (∼5 minutes long) for eight weeks. Daily diaries were completed on a smartphone, tablet, or computer and managed through an online website with a secure interface. Unique links for diaries were emailed to participants and/or their caregivers daily between 1:00 p.m. and 3:00 p.m. per family preferences. If diaries were not completed by 5:30 p.m., a reminder text was sent to the caregiver, participant, or both based on preferences. Youth were instructed to complete diaries by 10:00 p.m. each day. Follow-up contact was made if no diaries were completed for three consecutive days to identify and help resolve any obstacles that occurred for participation. Participants received $10 for completing baseline measures and $1 for each diary completed.

Measures

Baseline Measures

Baseline measures were collected to characterize the study sample and likely generalizability of the results to other youth with SCD.

The Psychosocial Assessment Tool 2.0 (PAT 2.0) is a 69-item parent/caregiver measure assessing psychosocial functioning of the child and family. The PAT 2.0 includes seven subscales (Family Structure/Resources, Child Problems, Sibling Problems, Parent Stress Reaction, Family Beliefs) and a Total Score and has been shown to be reliable and valid in populations with SCD (Karlson et al., 2012).

The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Multidimensional Fatigue Scale (PedsQL MFS) is an 18-item scale measuring dimensions of fatigue (e.g., general, sleep/rest, cognitive) in children through parent and youth report (child inventory for ages 8–12, adolescent inventory for ages 13–18) (Anderson et al., 2015).

The Stress Appraisal Measure for Adolescents (SAMA) is a 14-item questionnaire designed for youth 14–18 years of age measuring primary (threat) and secondary (challenge) cognitive appraisal of stress based on a 5-point Likert scale (Rowley et al., 2005). It includes three subscales/domains (Threat, Challenge, Resources) (Carpenter, 2016).

The Children’s Depression Inventory-Second Edition (CDI-2) is a 28-item questionnaire assessing depressive symptoms in youth 7–17 years and yields a Total Score and scores for Emotional Problems and Functional Problems (Bae, 2012).

The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children-Second Edition (MASC-2) is a 50-item scale assessing anxiety in youth 8–19 years with an overall score and seven subscales (Separation Anxiety/Phobias, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Index, Social Anxiety, Obsessions and Compulsions, Physical Symptoms, Harm Avoidance, and an Inconsistency Index) (Baldwin & Dadds, 2007).

Daily Diary Questions/Measures

Fatigue was measured by asking the participants to rate the severity, bother, and interference of their fatigue on a scale of 0–10 (0 equals no fatigue, no bother, or no interference; 10 equals worst fatigue, worst bother, worst interference). This method of fatigue has been used among adolescents receiving chemotherapy (Erickson et al., 2010) and similar rating scales and visual analog scales have been used in other studies to measure daily fatigue (Ream et al., 2006; Schwartz, 2000). Fatigue severity was used as the primary measure of fatigue.

The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule for Children (PANAS-C) is a 27-item measure of PA and NA among children. The PANAS-C is a widely used measure of PA and NA, and it has demonstrated validity in school and clinic-referred populations (Chorpita & Daleiden, 2002).

Cognitive appraisal of stress was measured in the daily diary using the three items with the highest factor loading from each of the Threat, Challenge, and Resources subscales of the SAMA (Rowley et al., 2005). Threat endorsement was used as the measure of primary cognitive appraisal of stress using the item “Stressful events impact me greatly.” Challenge endorsement was used as a measure of secondary appraisal of stress using the item “I have the ability to overcome stress.”

Pain intensity was measured by asking participants to rate their current pain intensity on a scale of 0–10. This method is listed among evidenced based measures from the Society of Pediatric Society as a measure “approaching well-established” status and is used commonly among pediatric populations (Richardson et al., 1983).

Sleep quality was measured by participants rating the quality of their prior nights’ sleep on a 0–10 NRS with 0 indicating “poor” sleep and 10 indicating “ideal” sleep quality. This method has been used in studies of youth with SCD and is established as reliable and valid (Bromberg et al., 2012; Valrie et al., 2007).

Data Analysis

Participants completing at least nine daily diaries and consecutive diaries that allowed for lagged analyses (i.e., “diary completers”) were included to test study aims. Means and standard deviations for baseline measures were compared for diary completers and non-completers to assess for inclusion bias.

Daily diary data analyses were conducted using R software version 4.1.2 and were modeled from similar diary study methods used previously (Johnston et al., 2022; Schatz et al., 2015). A three-step approach was taken for analyses between same-day and prospective variables: (1) fitting an error structure to correct for serial dependency, (2) modeling age, genotype, gender, time of diary completion, and number of diaries completed to determine their inclusion as covariates, and (3) adding predictors. As part of fitting an error structure, a “Day” variable was included to correct for serial dependency. For the error structure, an auto-regressive, moving average (ARMA) was used. A person-level predictor of variables was added to control for any between-person effects, which is needed to avoid conflating Level 1 and Level 2 effects in multi-level models. To test the statistical significance of the overall model a likelihood ratio test that compared the −2 log likelihood of the model was compared between a model with only the “day” variable as an independent variable and the full model. A pseudo R2 was computed for each model as described by Finch and French (2014) comparing the full model for the hypothesis to the null model with the formula:

For comparisons of models with versus without interaction terms, the approach above was used to compare the two models and generate an incremental R2.

The appropriateness of the MLM analyses was tested in each statistical model through one-way analysis of variance to test for significant between groups variance and random coefficient regression models to test for a significant pooled within-groups slope and significant variance in intercepts and slopes. The assumptions of linearity, homogeneity of variance, and normally distributed residuals were examined through visual inspection of graphs plotting: the model residuals versus each predictor variable, fitted values versus residuals, and a histogram of the residuals, respectively. Given the dearth of studies in this area, a test-wise alpha level of 0.05 was chosen to interpret analyses. Data are available upon request.

Results

Twenty-five youths with SCD aged 11–18 years were diary completers (Table I). Among the completers there were 819 total diaries (M = 32.0; SD = 17.0; range 9–56) for a 58.5% adherence rate to diary completion. There were no statistically significant differences or effect sizes of d ≥ 0.20 between diary completers and non-completers on demographic or baseline measures. Descriptive statistics were conducted to examine sample characteristics at baseline for the 25 completers (Table I). The baseline psychosocial information for our sample showed slightly lower overall psychosocial risk scores on the PAT, highly similar total scores for fatigue, and slightly higher scores for depression and anxiety symptoms than other recent studies of youth with SCD (Heitzer et al., 2022; Panepinto et al., 2014; Reader, Keeler et al., 2020; Reader, Rockman et al., 2020).

Table I.

Descriptive Information for Study Sample (n = 25)

| Variable | N | M ± SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | – | 14.3 ± 1.9 | 11.3–18.5 |

| Gender | – | – | |

| Male | 15 (60%) | ||

| Female) | 10 (40%) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black/African-American | 24 (92%) | ||

| Multi-racial | 1 (8%) | ||

| Primary caregiver highest education | |||

| Did not complete high school/GED | 1 (4%) | ||

| Completed high school/GED | 9 (36%) | ||

| Completed college or trade school | 12 (48%) | ||

| Completed graduate degree | 3 (12%) | ||

| Sickle cell genotype | |||

| Severe: HbSS | 16 (64%) | – | – |

| HbSβthal0 | 2 (8%) | – | – |

| Moderate: HbSC | 4 (16%) | – | – |

| HbSβthal+ | 3 (12%) | – | – |

| Psychosocial variables | |||

| PAT overall risk level (possible range 0–7) | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 0.1–1.7 | |

| Multi-dimensional Fatigue Scale General Fatigue | |||

| Parent proxy report (possible scores 0–100) | 60.1 ± 26.0 | 25.0–100.0 | |

| Multi-dimensional Fatigue Scale General Fatigue | |||

| Youth report (possible scores 0–100) | 60.5 ± 16.8 | 12.5–87.5 | |

| Stress Appraisal Measure for Adolescents | |||

| Threat (possible scores 0–4) | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 0.0–3.2 | |

| Challenge (possible scores 0–4) | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 0.2–3.8 | |

| Resources (possible scores 0–4) | 3.1 ± 1.0 | 0.0–4.0 | |

| CDI—youth report (norm referenced T-score) | 57.0 ± 10.6 | 40.0–84.0 | |

| MASC—youth report (norm referenced T-score) | 58.0 ± 11.6 | 40.0–75.0 |

Note. CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory, 2nd edition; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Inventory for Children, 2nd edition; PAT = Psychosocial Assessment Tool (v. 2.0).

Potential covariates (age, gender, genotype severity, time of diary completion, number of diaries completed) were tested for covariation, but were not significantly associated with the dependent variables in the multi-level regression analyses. We trimmed data that did not include necessary lagged variables to create a consistent data set across all analyses, yielding a total of 644 diary entries for the analyses described below. Effect size analyses indicated that with 644 diaries and a p-level of .05, Level 1 variables in our most complex regression could be detected if their effects size was d ≥ 0.16. A priori power was not calculated given its dependence on unknown variables without estimates available, such as the variance expected at both Level 1 and Level 2, the strength of the intraclass coefficient, and the impact of covariates on between group variance (Scherbaum & Ferreter, 2009). Summary data for key variables from the 644 diary entries are provided in Table II. Due to their typical skewed distribution, we elaborate further on fatigue and pain ratings here. Fatigue ratings showed 259 cases with ratings ≥0, reflecting the presence of fatigue, and 84 cases of scores ≥4, which we defined as moderate fatigue. Pain ratings showed 190 cases with ratings ≥0 and 62 cases of scores of ≥4.

Table II.

Descriptive Statistics for Key Study Variables Across the Daily Diary Period

| Variable (possible scores) | M ± SD | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue (0–10) | 1.21 ± 2.10 | 0–10 |

| Pain intensity (0–10) | 0.87 ± 1.83 | 0–10 |

| Sleep quality | 7.24 ± 2.60 | 0–10 |

| Positive affect (12–60) | 36.32 ± 15.88 | 12–60 |

| Negative affect (15–75) | 17.97 ± 5.26 | 15–54 |

| Primary stress appraisal | 1.44 ± 1.37 | 0–4 |

| Secondary stress appraisal | 2.86 ± 1.46 | 0–4 |

Note. Fatigue = fatigue severity 0–10; pain intensity = pain 0–10; positive and negative affect = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule for Children; primary stress appraisal = endorsement of “Stressful events impact me greatly”; secondary stress appraisal = endorsement of “I have the ability to overcome stress.”

Concurrent Relationships among Fatigue and Mood (Hypothesis 1)

The overall model testing the relationship between daily fatigue severity and mood was statistically significant, χ2(10) = 98.57, p < .001, R2 = 0.35 (Table III). Consistent with our hypothesis, increased fatigue was significantly associated with greater negative mood, t(1,614) = 3.23, p < .001, d = 0.26, while controlling for effects of pain, t(1,614) = 5.30, p < .001, d = 0.43, and sleep quality t(1,614) = −3.51, p < .001, d = 0.28. Contrary to our hypothesis, increased fatigue did no meet our alpha criteria for an association with same-day positive mood, t(1,614) = −1.62, p = .11, d = 0.13.

Table III.

Same-Day Associations With Fatigue Severity

| Variable | B | SE | 95% CI | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same-day fatigue severity | ||||

| Intercept | 2.02 | 0.29 | 1.45, 2.59 | 7.02*** |

| Day | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.03, −0.01 | −4.26*** |

| Person-level fatigue | 2.39 | 0.34 | 1.69, 3.09 | 7.06*** |

| Pain intensity | 0.41 | 0.08 | 0.26, 0.56 | 5.30*** |

| Sleep quality | −0.31 | 0.09 | −0.48, −0.14 | −3.51 |

| Positive affect | −0.23 | 0.14 | −0.50, 0.05 | −1.62 |

| Negative affect | 0.50 | 0.15 | 0.20, 0.80 | 3.23** |

Note. Intercept, day, and person-level fatigue are included as part of the analytic approach but are not of substantive interest. Fatigue = NRS 0–10; pain intensity = NRS 0–10; positive and negative affect = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule for Children; sleep quality = NRS 0–10.

** p < .01.

*** p < .001.

Lagged Analyses Predicting Next-Day Mood (Hypothesis 2)

Four models were run to examine potential interactions between the cognitive appraisal of stress (primary/threat and secondary/challenge) and fatigue on next-day affective experience (PA, NA). For analyses with next-day PA as the dependent variable the overall statistical model using primary, χ2(11) = 39.84, p < .001, R2 = 0.35, and secondary stress appraisal, χ2(11) = 38.99, p < .001, R2 = 0.36, were each statistically significant; however, both the main effects for fatigue and stress appraisal, and their interaction were not statistically significant (all ps > .12; all ds < 0.10).

For analyses with NA as the dependent variable the overall statistical model using primary, χ2(11) = 28.01, p < .001, R2 = 0.23, and secondary stress appraisal, χ2(11) = 27.80, p < .001, R2 = 0.22, were each statistically significant (see Table IV). The interaction terms for Fatigue and Cognitive Appraisal were statistically significant for primary, t(1,612) = 2.97, p < .01, d = 0.24, and secondary, t(1,612) = 2.99, p < .01, d = 0.24, stress appraisal. We decomposed these interactions by running the same statistical models predicating next-day NA but running these separately for days with lower fatigue (ratings of 0 to 4; n = 561) versus days with higher fatigue (ratings of 5–10; n = 83).

Table IV.

Test of Hypothesized Moderation Effect for Next-Day Negative Affect Assessed for Both Primary and Secondary Stress Appraisals

| Variable | B | SE | 95% CI | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Next-day negative affect | ||||

| Intercept | 13.57 | 0.59 | 12.42, 14.72 | 23.13*** |

| Day | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03, 0.01 | −1.39 |

| Person-level negative affect | 0.45 | 0.10 | 0.25, 0.66 | 4.56*** |

| Negative affect | 4.79 | 0.36 | 4.08, 5.50 | 13.29*** |

| Pain intensity | 0.00 | 0.17 | −0.34, 0.34 | 0.01 |

| Sleep quality | −0.28 | 0.20 | −0.67, 0.10 | −1.45 |

| Fatigue severity | −0.11 | 0.21 | −0.52, 0.30 | −0.53 |

| Primary stress appraisal | −0.07 | 0.21 | −0.49, 0.35 | 0.34 |

| Fatigue severity × primary stress appraisal | 0.60 | 0.20 | 0.20, 0.99 | 2.97** |

| Next-day negative affect | ||||

| Intercept | 13.64 | 0.61 | 12.45, 14.83 | 22.52*** |

| Day | −0.011 | 0.01 | −0.03, 0.01 | −1.30 |

| Person-level negative affect | 0.24 | 0.13 | −0.02, 0.51 | 1.91 |

| Negative affect | 4.97 | 0.36 | 4.26, 5.67 | 13.83*** |

| Pain intensity | 0.03 | 0.17 | −0.31, 0.37 | 0.18 |

| Sleep quality | −0.20 | 0.21 | −0.61, 0.20 | −0.99 |

| Fatigue severity | 0.03 | 0.20 | −0.36, 0.43 | 0.17 |

| Secondary stress appraisal | 0.13 | 0.26 | −0.38, 0.64 | 0.50 |

| Fatigue severity × secondary stress appraisal | 0.66 | 0.22 | 0.22, 1.09 | 2.99** |

Note. Intercept, day, and person-level negative affect are included as part of the analytic approach but are not of substantive interest. Fatigue severity = fatigue severity 0–10; pain intensity = pain 0–10; positive and negative affect = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule for Children; primary stress appraisal = endorsement of “Stressful events impact me greatly”; secondary stress appraisal = endorsement of “I have the ability to overcome stress.”

p < .01.

p < .001.

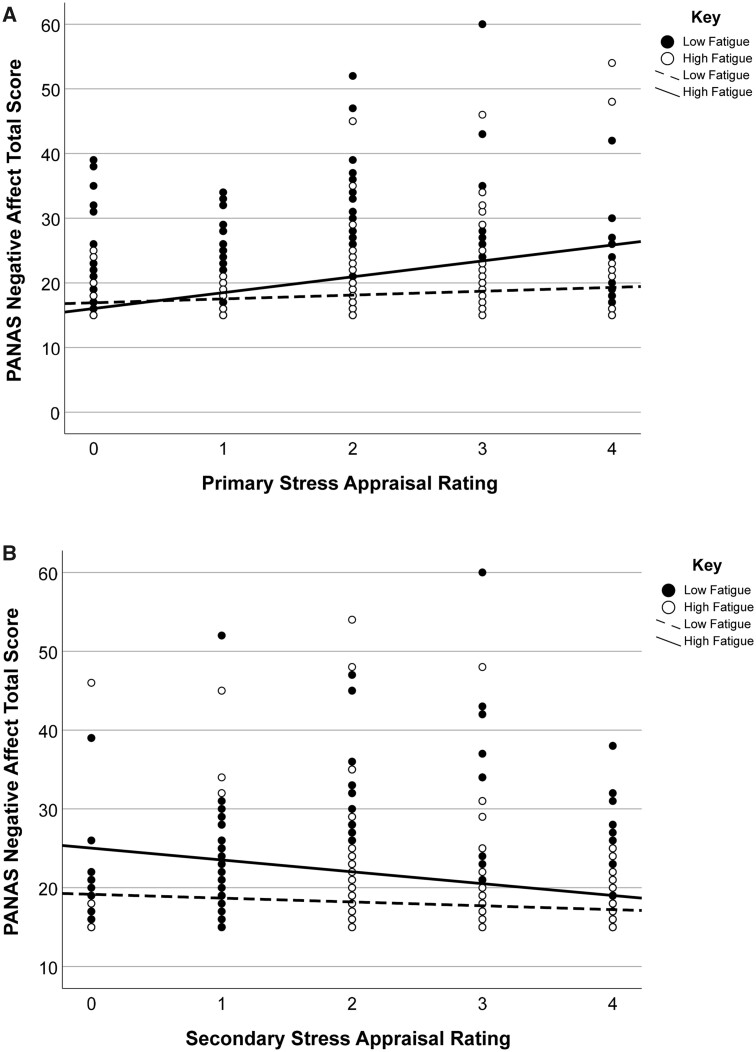

On days with higher fatigue the model for primary stress appraisal showed a statistically significant overall model, χ2(11) = 50.33, p < .001, R2 = 0.27, and primary stress appraisal predicted next-day negative mood, t(1,45) = 3.89, p < .001. On days with lower fatigue, the model for primary stress appraisal was statistically significant, χ2(11) = 20.98, p = .004, R2 = 0.08, but primary stress appraisal was not related to next-day negative mood, t(1,548) = 0.16, p = .11. Secondary stress appraisal demonstrated the same pattern of statistical significance with significant overall models for both days with higher, χ2(11) = 38.46, p < .001, R2 = 0.20, and lower, χ2(11) = 20.81, p = .004, R2 = 0.08, ratings for fatigue. Secondary stress appraisal predicted next-day NA on days with higher fatigue, t(1,45) = −2.22, p = .03, but not on days with lower fatigue, t(1,45) = −0.37, p = .71. These interaction effects are shown in Figure 1 using the un-centered variables for easier interpretation.

Figure 1.

Interactions between level of fatigue and cognitive appraisal of stress in predicting next-day negative mood. Primary stress appraisal (A) assesses the extent of perceived threat from stressors whereas secondary appraisal (B) assesses confidence in one’s ability to overcome stressors. On days with higher fatigue, high perceived threat and low confidence in overcoming stress increased next-day negative mood. On days with lower fatigue, this relationship was not found. Fatigue severity = fatigue severity 0–1; positive and negative affect = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule for Children (PANAS); primary stress appraisal = endorsement of “Stressful events impact me greatly”; secondary stress appraisal = endorsement of “I have the ability to overcome stress.”

Post Hoc Analyses

Given that fatigue and pain are both SCD stressors proposed to play similar roles in the Risk-and-Resistance Model, we evaluated if cognitive appraisal showed a similar moderation effect for pain intensity’s impact on next-day negative mood as it did for fatigue. Two parallel models, as run to test Hypothesis 2, were run except that the interaction terms for pain intensity and cognitive appraisal (primary, secondary) were included instead of the fatigue by cognitive appraisal interaction terms. The overall statistical significance of each model and predictor variables were highly similar to the analyses for Hypothesis 2 (primary stress model: χ2(11) = 27.90, p < .001, R2 = 0.22; secondary stress model: χ2(11) = 26.99, p < .001, R2 = 0.21. The interaction terms for Pain and Cognitive Appraisal were statistically significant for primary, t(1,612) = 3.04, p < .01, d = 0.25, and secondary, t(1,612) = 3.00, p < .01, d = 0.24, stress appraisal. When decomposed as done above for Hypothesis 2, a similar pattern emerged with cognitive appraisal appearing to have a protective effect on next-day NA (data not shown).

Discussion

The current study evaluated the relationship between fatigue and emotional functioning among youth with SCD within the context of the Risk-and-Resistance Model by assessing their concurrent and temporal relationships using daily diary methods, while statistically controlling for pain intensity and prior-night sleep quality. Stress appraisal was included as a moderating factor for fatigue in predicting next-day mood as expected from the Risk-and-Resistance Model (Wallander & Thompson, 1995). Cross-sectional analyses were consistent with prior studies showing associations between fatigue severity and negative mood (Ameringer et al., 2014; Anderson et al., 2015). We did not find the expected association between fatigue and positive mood. Prior studies have relied on measures of depression and anxiety symptoms to assess mood, which do not distinguish between positive and negative mood. Thus, differences in our measurement approach for emotional functioning may be important for our null finding. It would be useful for future studies to assess positive and negative mood separately to replicate the observed associations as each has implications for the risk for specific internalizing patterns, as elaborated below in our discussion of Hypothesis 2. Thus, our daily diary method partially supported our first hypothesis. Our second hypothesis was also partially supported with the expected moderation effect between fatigue and cognitive appraisal of stress predicting next-day negative mood, but not next-day positive mood.

Prior cross-sectional studies of fatigue and internalizing symptoms in SCD have shown that these constructs are associated. The authors have offered conceptual explanations as to how mutual causality may be responsible for the associations (Ameringer et al., 2014; Ameringer & Smith, 2011). We previously observed a temporal association with negative mood predicting next-day fatigue levels when controlling for the effects of pain intensity and subjective sleep quality (Johnston et al., 2022). In the present study, we evaluated stress appraisal as a cognitive factor that was expected to moderate the impact of fatigue on later mood based on the Risk-and-Resistance Model of Chronic Illness. Partial support for a moderating role was found with fatigue severity and cognitive appraisal interacting to predict next-day negative mood. These effects were observed above and beyond the impact of subjective sleep quality, indicating the importance of assessing for fatigue, sleepiness, and sleep quality as distinct (but overlapping) constructs that can impact mood (Shahid et al., 2010). Though not the primary focus of this study, a similar effect was observed for pain severity interacting with cognitive appraisal to predict next-day negative mood, suggesting that cognitive appraisal may serve as a more general moderator of SCD stressor’s impact on emotional functioning. These moderating effects are important for informing how coping could mitigate the negative impacts of fatigue on emotional functioning. Prior research has demonstrated that stress appraisal is situation specific and beliefs about the degree of threat and challenge can be altered through message framing around the nature of stress and other cognitive therapy techniques (Crum et al., 2017; Telman et al, 2013). Taken together with the present data, this suggests that negative mood may not be an inevitable impact of fatigue and that cognitive coping techniques, such as cognitive reappraisal, could be useful to reduce negative mood as a downstream effect from fatigue. The observed associations in the present study, however, showed relatively small effect sizes and the extent to which techniques such as cognitive reappraisal could impact patient wellbeing is unknown. Future studies should examine the impact of altering cognitive appraisals of stress in youth with SCD to assess if this reduces negative mood in response to SCD stressors.

The finding of a dissociation between effects on positive versus negative mood in the concurrent and longitudinal relationships observed may also be useful for considering the antecedents of internalizing symptoms in SCD. According to the tripartite model of anxiety and depression, increased negative mood would be expected to increase the risk for both anxiety and depression (Anderson & Hope, 2008). If our hypothesized effect of fatigue decreasing positive mood were also to have been found, this would have suggested a more specific increased risk for depression. Thus, the data pattern in the present study is consistent with prior observations of an association of fatigue with both anxiety and depressive symptoms in SCD. Depressive symptoms have received somewhat more attention in studies of fatigue to-date; future studies should include measures of both types of internalizing symptoms.

The results of this study should be considered in the context of several important study limitations. As with many studies using daily diary methods in SCD, we found adherence to completing daily diaries to be difficult for many of the participants (Schatz et al., 2015; Valrie et al., 2019). Our 25 diary completers submitted diaries on ∼60% of the study days and our 7 non-completers struggled even more to complete diaries. In a prior study, most failures to complete diaries were reported to be due to factors such as forgetting or temporarily losing track of the device used for diary completion, rather than selectively reporting on days with more or fewer symptoms (Schatz et al., 2015). Nonetheless, the generalizability of the data to youth with SCD may be limited by the total number of participants and uneven sampling within participants. We collected extensive baseline data to assess for relevant psychological factors that could be important for generalizability of the sample. We did not observe differences between completers and non-completers for demographics or other baseline measures, and the baseline psychosocial information for our sample was not markedly different than those reported in other studies of youth with SCD (Heitzer et al., 2022; Panepinto et al., 2014; Reader, Keeler et al., 2020; Reader, Rockman et al., 2020). Nonetheless, replication of results is particularly important given these limitations. It should also be noted that bias may exist in the sample regardless of completer/non-completer status due to participants being recruited from clinic appointments and thus representing participants who are adherent to medical care. Statistical power itself did not appear to be a significant concern for detecting effects of d ≥ 0.16, which are typically considered small effect sizes. Daily diary methods allow for assessing temporal relationships but do not guarantee that one is capturing the critical time window for the temporal effects of interest. For example, ecological momentary analysis methods may collect multiple reports per day, allowing for a timescale of hour-by-hour changes rather than a whole day, which could detect temporal associations not captured by the daily diary method. Our measurement of the cognitive appraisal of stress in diaries was based on a single item from the SAMA, which may limit the full construct representation of primary and secondary stress appraisal.

The present study adds to our understanding of the role of fatigue in emotional functioning among youth with SCD. The use of longitudinal methods appears to be important for understanding the causal pathways among these constructs. Future work is needed to provide converging support for the present findings and to test whether modifying beliefs about stress can reduce the impact of fatigue on negative mood in SCD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was completed as part of the doctoral requirements for the first author.

Contributor Information

Laura Reinman, Department of Psychiatry, University of Colorado School of Medicine, USA.

Jeffrey Schatz, Department of Psychology, University of South Carolina, USA.

Julia Johnston, Department of Psychology, University of South Carolina, USA.

Sarah Bills, Department of Psychology, University of South Carolina, USA.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data can be found at: https://academic.oup.com/jpepsy.

Author Contributions

Laura Reinman (Conceptualization [lead], Data curation [equal], Formal analysis [supporting], Investigation [lead], Methodology [supporting], Project administration [lead], Resources [equal], Validation [lead], Writing—original draft [lead], Writing—review & editing [lead]), Jeffrey Schatz (Conceptualization [supporting], Data curation [equal], Formal analysis [lead], Investigation [supporting], Methodology [lead], Resources [equal], Software [lead], Supervision [lead], Writing—original draft [supporting], Writing—review & editing [supporting]), Julia DeAun Johnston (Data curation, Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing [supporting]), and Sarah Bills (Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Validation, Writing—review & editing [supporting])

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by Grant Number T32-GM081740 from National Institutes of Health-National Institute of General Medical Sciences. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIGMS or NIH.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- Ameringer S., Elswick R. K. Jr., Smith W. (2014). Fatigue in adolescents and young adults with sickle cell disease: Biological and behavioral correlates and health-related quality of life. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 31(1), 6–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameringer S., Smith W. R. (2011). Emerging biobehavioral factors of fatigue in sickle cell disease. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 43(1), 22–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson L. M., Allen T. M., Thornburg C. D., Bonner M. J. (2015). Fatigue in children with sickle cell disease: Association with neurocognitive and social-emotional functioning and quality of life. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 37(8), 584–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. R., Hope D. A. (2008). A review of the tripartite model for understanding the link between anxiety and depression in youth. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(2), 275–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae Y. (2012). Test review: Children’s depression inventory 2 (CDI 2). Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 30(3), 304–308.

- Baldwin J. S., Dadds M. R. (2007). Reliability and validity of parent and child versions of the multidimensional anxiety scale for children in community samples. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(2), 252–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballas S. K., Lieff S., Benjamin L. J., Dampier C. D., Heeney M. M., Hoppe C., Johnson C. S., Rogers Z. R., Smith-Whitley K., Wang W. C., Telen M. J.; Investigators, Comprehensive Sickle Cell Centers (2010). Definitions of the phenotypic manifestations of sickle cell disease. American Journal of Hematology, 85(1), 6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat L. P., Lash L. A., Lutz M. J., Nicolaou D. C. (2006). Psychosocial adaptation of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. In Brown, R. T. (Ed), Comprehensive handbook of childhood cancer and sickle cell disease: A biopsychosocial approach (pp. 471–495). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benton T. D., Ifeagwu J. A., Smith-Whitley K. (2007). Anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Current Psychiatry Reports, 9(2), 114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg M. H., Gil K. M., Schanberg L. E. (2012). Daily sleep quality and mood as predictors of pain in children with juvenile polyarticular arthritis. Health Psychology, 31(2), 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter R. (2016). A review of instruments on cognitive appraisal of stress. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 30(2), 271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier M. Y., Elkin T. D., Starnes S. E. (2009). Behavioral inhibition and its relation to anxiety and depression symptoms in adolescents with sickle cell disease: A preliminary study. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 26(3), 158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver C. S., Vargas S. (2011). Stress, coping, and health. The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology, 162–188. [Google Scholar]

- Crum A. J., Akinola M., Martin A., Fath S. (2017). The role of stress mindset in shaping cognitive, emotional, and physiological responses to challenging and threatening stress. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 30(4), 379–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita B. F., Daleiden E. L. (2002). Tripartite dimensions of emotion in a child clinical sample: Measurement strategies and implications for clinical utility. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(5), 1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crichton A., Knight S., Oakley E., Babl F. E., Anderson V. (2015). Fatigue in child chronic health conditions: A systematic review of assessment instruments. Pediatrics, 135(4), e1015–e1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll M. C. (2007). Sickle cell disease. Pediatrics in Review, 28(7), 259–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekinci Ö., Çelik T., Ünal Ş., Özer C. (2012). Psychiatric problems in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease, based on parent and teacher reports. Turkish Journal of Hematology, 29(3), 259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson J. M., , BeckS. L., , ChristianB., , DudleyW. N., , HollenP. J., , AlbrittonK., , SennettM. M., , DillonR., & , Godder K. (2010). Patterns of fatigue in adolescents receiving chemotherapy. Oncology Nursing Forum, 37(4), 444–455. 10.1188/10.ONF.444-455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch W. H., French B. F. (2014). Multilevel latent class analysis: Parametric and nonparametric models. The Journal of Experimental Education, 82(3), 307–333. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein-Fox L., Park C. L., Riley K. E. (2019). Mindfulness’ effects on stress, coping, and mood: A daily diary goodness-of-fit study. Emotion, 19(6), 1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartland N., O'Connor D. B., Lawton R., Bristow M. (2014). Exploring day-to-day dynamics of daily stressor appraisals, physical symptoms and the cortisol awakening response. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 50, 130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil K. M., Carson J. W., Porter L. S., Ready J., Valrie C., Redding-Lallinger R., Daeschner C. (2003). Daily stress and mood and their association with pain, health-care use, and school activity in adolescents with sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 28(5), 363–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassell K. L. (2010). Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 38, 512–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitzer A. M., Longoria J., Porter J. S. (2022). Internalizing symptoms in adolescents with sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 48(1), 91–103. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsac068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijmans C. T., Grootenhuis M. A., Oosterlaan J., Last B. F., Heijboer H., Peters M., Fijnvandraat K. (2009). Behavioral and emotional problems in children with sickle cell disease and healthy siblings: Multiple informants, multiple measures. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 53(7), 1277–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerrell J. M., Tripathi A., McIntyre R. S. (2011). Prevalence and treatment of depression in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease: A retrospective cohort study. Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 13(2). doi: 10.4088/PCC.10m01063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston J. D., Reinman L. C., Bills S. E., Schatz J. C. (2022). Sleep and fatigue among youth with sickle cell disease: A daily diary study. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 5, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10865-022-00368-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlson C. W., Leist-Haynes S., Smith M., Faith M. A., Elkin T. D., Megason G. (2012). Examination of risk and resiliency in a pediatric sickle cell disease population using the psychosocial assessment tool 2.0. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 37(9), 1031–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R. S., Folkman S. (1984). Coping and adaptation. In Gentry, W. D. (Ed.), The Handbook of Behavioral Medicine, (pp. 282–325). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Levine J., Greenwald B. D. (2009). Fatigue in Parkinson disease, stroke, and traumatic brain injury. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 20(2), 347–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K. R., He J. P., Burstein M. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panepinto J. A., Bonner M. (2012). Health‐related quality of life in sickle cell disease: Past, present, and future. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 59(2), 377–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panepinto J. A., Torres S., Bendo C. B., McCavit T. L., Dinu B., Sherman-Bien S., Bemrich-Stolz C., Varni J. W. (2014). PedsQL™ Multidimensional Fatigue Scale in sickle cell disease: Feasibility, reliability, and validity. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 61(1), 171–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reader S. K., Keeler C. N., Chen F. F., Ruppe, N. M., Rash-Ellis, D. L., Wadman, J., Miller, R. E., & Kazak, A. E. (2020). Psychosocial screening in sickle cell disease: Validation of the Psychosocial Assessment Tool. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 45(4), 423–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reader S. K., Rockman L. M., Okonak K. M., Ruppe, N. M., Keeler, C. N., & Kazak, A. E. (2020). Systematic review: Pain and emotional functioning in pediatric sickle cell disease. J Clin Psychol Med Settings, 27, 343–365. 10.1007/s10880-019-09647-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ream E., Gibson F., Edwards J., Seption B., Mulhall A., Richardson A. (2006). Experience of fatigue in adolescents living with cancer. Cancer Nursing, 29(4), 317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinman L. (2019). Risk and resistance factors for depression and anxiety among youth with sickle cell disease [Doctoral dissertation, University of South Carolina]. University of South Carolina Scholar Commons.

- Richardson G. M., McGrath P. J., Cunningham S., Humphreys P. (1983). Validity of the headache diary for children. Headache, 23(4), 184–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley A. A., Roesch S. C., Jurica B. J., Vaughn A. A. (2005). Developing and validating a stress appraisal measure for minority adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 28(4), 547–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz J., Schlenz A., McClellan C. B., Puffer E. S., Hardy S., Pfeiffer M., Roberts C. W. (2015). Changes in coping, pain and activity following cognitive-behavioral training: A randomized clinical trial for pediatric sickle cell disease using smartphones. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 31(6), 536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherbaum C. A., Ferreter J. M. (2009). Estimating statistical power and required sample sizes for organizational research using multilevel modeling. Organizational Research Methods, 12(2), 347–367. [Google Scholar]

- Schlenz A. M., Schatz J., Roberts C. W. (2016). Examining biopsychosocial factors in relation to multiple pain features in pediatric sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 41(8), 930–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz A. L. (2000). Daily fatigue patterns and effect of exercise in women with breast cancer. Cancer Practice, 8(1), 16–24. 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2000.81003.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahid A., Shen J., Shapiro C. M. (2010). Measurements of sleepiness and fatigue. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69(1), 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon K., Barakat L. P., Patterson C. A., Dampier C. (2009). Symptoms of depression and anxiety in adolescents with sickle cell disease: The role of intrapersonal characteristics and stress processing variables. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 40(2), 317–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltani S., Kopala-Sibley D. C., Noel M. (2019). The co-occurrence of pediatric chronic pain and depression. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 35(7), 633–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telman M. D., Holmes E. A., Lau J. Y. (2013). Modifying adolescent interpretation biases through cognitive training: Effects on negative affect and stress appraisals. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 44(5), 602–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. J. Jr., Armstrong F. D., Link C. L., Pegelow C. H., Moser F., Wang W. C. (2003). A prospective study of the relationship over time of behavior problems, intellectual functioning, and family functioning in children with sickle cell disease: A report from the Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 28(1), 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao J. C., Jacob E., Seidman L. C., Lewis M. A., Zeltzer L. K. (2014). Psychological aspects and hospitalization for pain crises in youth with sickle-cell disease. Journal of Health Psychology, 19(3), 407–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valrie C., Floyd A., Sisler I., Redding-Lallinger R., Fuh B. (2020). Depression and anxiety as moderators of the pain-social functioning relationship in youth with sickle cell disease. Journal of Pain Research, 13, 729–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valrie C. R., Gil K. M., Redding-Lallinger R., Daeschner C. (2007). Brief report: Sleep in children with sickle cell disease: An analysis of daily diaries utilizing multilevel models. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32(7), 857–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valrie C. R., Kilpatrick R. L., Alston K., Trout K., Redding-Lallinger R. R., Sisler I., Fuh B. (2019). Investigating the sleep-pain relationship in youth with sickle cell utilizing mHealth Technology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 44(3), 323–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallander J., Thompson R. Jr. (1995). Psychosocial adjustment of children with chronic physical conditions. In Roberts, M. C. (Ed.), Handbook of pediatric psychology (pp. 124–141). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- While A. E., Mullen J. (2004). Living with sickle cell disease: The perspective of young people. British Journal of Nursing, 13(6), 320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills K. E. (2013). Sickle cell disease. In Baron I. & Rey-Cassely S. (Eds.), Pediatric neuropsychology medical advances and lifespan outcomes (pp. 257–278). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ziadni M. S., Patterson C. A., Pulgarón E. R., Robinson M. R., Barakat L. P. (2011). Health-related quality of life and adaptive behaviors of adolescents with sickle cell disease: Stress processing moderators. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 18(4), 335–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.