Abstract

Objectives. To describe trends in the number of air travelers categorized as infectious with SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; the virus that causes COVID-19) in the context of total US COVID-19 vaccinations administered, and overall case counts of SARS-CoV-2 in the United States.

Methods. We searched the Quarantine Activity Reporting System (QARS) database for travelers with inbound international or domestic air travel, a positive SARS-CoV-2 lab result, and a surveillance categorization of SARS-CoV-2 infection reported during January 2020 to December 2021. Travelers were categorized as infectious during travel if they had arrival dates from 2 days before to 10 days after symptom onset or a positive viral test.

Results. We identified 80 715 persons meeting our inclusion criteria; 67 445 persons (83.6%) had at least 1 symptom reported. Of 67 445 symptomatic passengers, 43 884 (65.1%) reported an initial symptom onset date after their flight arrival date. The number of infectious travelers mirrored the overall number of US SARS-CoV-2 cases.

Conclusions. Most travelers in the study were asymptomatic during travel, and therefore unknowingly traveled while infectious. During periods of high community transmission, it is important for travelers to stay up to date with COVID-19 vaccinations and consider wearing a high-quality mask to decrease the risk of transmission. (Am J Public Health. 2023;113(8):904–908. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2023.307325)

Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; the virus that causes COVID-19) has been correlated with travel.1–3 Previous studies indicated that SARS-CoV-2 transmission events during and after air travel can be reduced with prevention strategies, including masking.4

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) operates 20 quarantine stations at US ports of entry with high volumes of arriving international travelers.5 Quarantine station personnel respond to ill travelers reported during travel and collect information on ill travelers identified after travel is completed. These data are entered and stored in an electronic record-keeping system, the Quarantine Activity Reporting System (QARS).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, partners reported to the CDC persons infected with SARS-CoV-2 with recent travel who were identified during routine case investigations and contact tracing.6 We performed a retrospective record review to describe the trends and characteristics of travelers identified as infectious with SARS-CoV-2 in the context of the initiation of US COVID-19–associated travel policies, US COVID-19 vaccinations administered, and US SARS-CoV-2 case counts.

METHODS

We queried the QARS database for all travelers with inbound international or domestic air travel with a positive SARS-CoV-2 lab result and a surveillance categorization of SARS-CoV-2 infection reported during January 2020 through December 2021.

We classified cases as infectious during travel if they were reported as having laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by a viral (i.e., nucleic acid amplification or antigen) test, and met 1 of the following conditions:

-

•

Reported COVID-19–compatible symptoms and flight arrival within the traveler’s infectious period, or

-

•

No reported COVID-19–compatible symptoms but flight arrival during the traveler’s infectious period.7

We determined infectious periods on the basis of CDC quarantine and isolation guidance during this period7 and defined them for analysis as follows:

-

•

Symptomatic travelers: from 2 days before symptom onset or initial positive viral test, whichever was earlier, until 10 days after.

-

•

Asymptomatic travelers: from 2 days before initial positive viral test until 10 days after.

Travelers with multiple legs of travel could be considered infectious on multiple flights. Although we did not measure infectiousness, we refer to passengers as infectious if they were within the infectious period described in the previous paragraphs.

We documented trends among travelers classified as infectious along with trends in overall traveler volume for domestic and inbound international flights, as well as trends in overall US SARS-CoV-2 cases and vaccination rates. Travel volume on domestic and inbound international flights was provided by the US Customs and Border Protection via the CDC’s Division of Global Migration and Quarantine’s Office of Innovation Development Evaluation and Analysis. We obtained the overall number of people with COVID-19 in the United States and vaccination information through the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.8

We plotted key mitigation policies implemented during our study period to provide context. The CDC issued orders aimed at reducing the number of people infected with SARS-CoV-2 entering the United States. Beginning January 26, 2021, the United States required all passengers arriving from international destinations to show proof of a negative test result for, or documented recovery from, SARS-CoV-2.9 Beginning February 1, 2021, the CDC required the use of masks on public transportation conveyances, including commercial aircraft, or on the premises of domestic transportation hubs.10 COVID-19 vaccines were initially made available to persons aged 16 years and older in mid-December 2020.11

RESULTS

During January 2020 through December 2021, 80 715 persons infectious with SARS-CoV-2 were reported to the CDC as having traveled on 125 135 domestic and 14 678 international inbound flights. Our data included 38 096 (47.2%) travelers identified as female, 35 186 (43.6%) identified as male, and 7433 (9.2%) reports in which gender was not specified. The mean age of passengers was 38.5 years (median = 36 years; range = 0–102 years).

Of the 80 715 travelers, 8523 (10.6%) were reported to be asymptomatic, 67 445 (83.6%) had at least 1 symptom reported, and 4747 (5.9%) were missing information on symptoms. Of 67 445 symptomatic passengers, 31 155 (46.1%) had onset of at least 1 symptom on or before their flight arrival date, and 43 884 (65.1%) reported an initial symptom onset date after their flight arrival date. These groups are not mutually exclusive, as passengers may have traveled on multiple flights across multiple days.

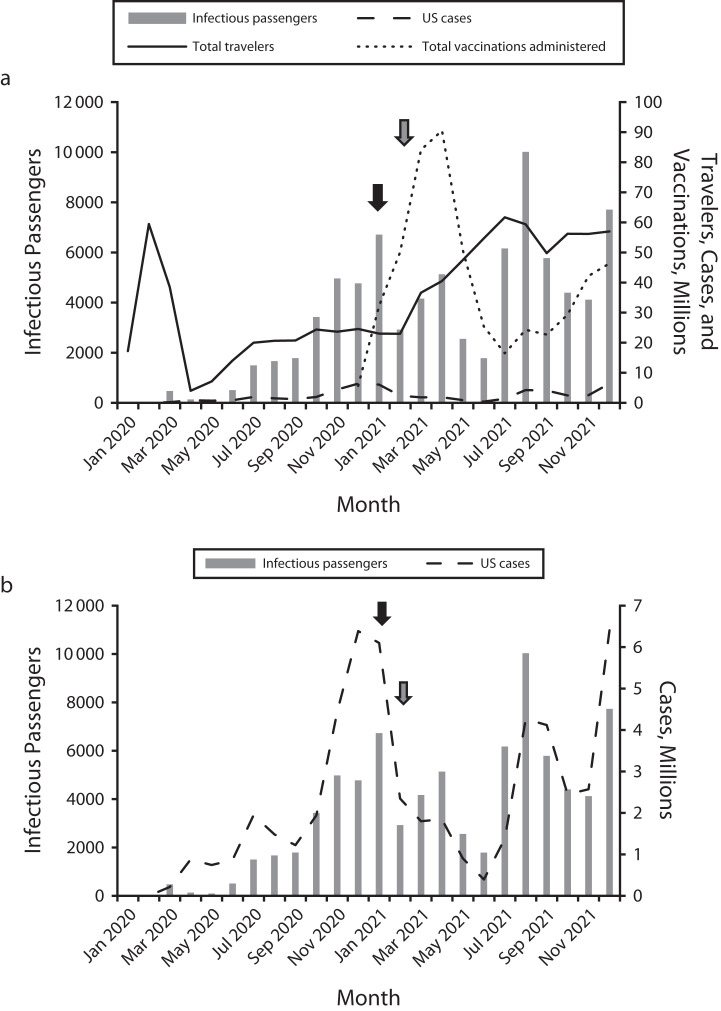

Trends in the monthly numbers of infectious travelers and of all travelers (regardless of SARS-CoV-2 infection status), vaccinations administered, and new SARS-CoV-2 infections in the United States are shown in Figure 1, along with the timing of key mitigation efforts affecting both domestic travelers and arriving international passengers. Figure 1 also shows new SARS-CoV-2 cases and the number of infectious travelers, along with date of initiation of CDC travel mitigation efforts. During fall 2020, the number of infectious travelers rose along with new US SARS-CoV-2 cases, peaking in January 2021; overall travel volume did not change. After January 2021, the number of infectious travelers fell sharply, as did overall monthly US cases, and then began to increase again as travel volume increased in March and April 2021. After April 2021, the monthly number of infectious travelers diverged from overall travel volume and closely paralleled the number of newly infected persons until July 2021. In July 2021, when overall travel volume peaked, the numbers of infectious travelers and new US cases also rose, peaking in August 2021 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Number of Infectious Passengers by (a) Number of US SARS-CoV-2 Cases, Number of Vaccines Administered in the United States, and Overall US Travel Volume per Month; and (b) Number of US SARS-CoV-2 Cases per Month: January 2020–December 2021

Note. SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) is the virus that causes COVID-19. Travel volume was determined by international inbound and domestic flights. Black arrow indicates the month when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) initiated testing requirements upon entry to the United States (January 26, 2021) and gray arrow indicates the date the CDC mandated face masks on public transport in the United States (February 1, 2021).

In early 2021, the CDC issued orders aimed at reducing the number of people infected with SARS-CoV-2 entering the United States, indicated in Figure 1 by black and gray arrows.9,10 A substantial drop in the numbers of infectious travelers and US cases can be seen in the months following these orders, concurrent with increased vaccinations administered, but numbers of infectious travelers and new SARS-CoV-2 cases rebounded during the summer months of 2021, following the overall trend in the number of travelers (Figure 1). This could be attributable to the increased number of US cases attributed to the Delta variant.

DISCUSSION

In general, beginning in the summer of 2020, the trend in the monthly number of infectious travelers follows the trend in new US SARS-CoV-2 cases. The decline in both infectious passengers and US cases in early 2021 could be attributable to several factors, including vaccine uptake, decreased community transmission, and unmeasured mitigation efforts. It is difficult to measure the direct impact of the CDC travel mitigation efforts on the number of infectious travelers because of the indirect way in which data were collected regarding adherence to the testing and masking requirements and other complex factors that affect transmission.

Of 67 445 symptomatic infectious passengers, 63% reported a symptom onset date after their flight arrival date. This indicates the potential for precautionary steps, including mask use and vaccination, to prevent transmission of infectious diseases—including asymptomatic transmission—during travel.

Our data likely underestimate the true number of persons who traveled while infectious, as persons who were infectious with SARS-CoV-2 during travel may not have been reported to the CDC. As community spread of SARS-CoV-2 increased, state and local health department partners prioritized other activities over case reporting to maximize their public health impact. Additionally, persons infected with SARS-CoV-2 may not have reported travel to public health to avoid cancelling their travel. These infected persons would not be captured in our data set.

The strengths of this analysis included a large data set; however, it is unclear whether it is representative of the population of US residents who travel. Because our data set was restricted to travelers with proof of laboratory confirmation in the report, all cases documented in our analysis were positive for SARS-CoV-2 by viral test. Travelers who were ill but not tested for SARS-CoV-2 would not be captured.

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

The number of infectious travelers mirrored the overall number of US SARS-CoV-2 cases. Fewer than half of the travelers classified as infectious during their flight were symptomatic during travel; therefore, some travelers unknowingly travel while infectious. It is important for travelers to stay current on COVID-19 vaccinations to decrease the risk of severe disease and consider wearing a high-quality mask during air travel, particularly travelers at higher risk of severe disease and when community transmission is high.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported in part by an appointment to the Research Participation Program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the US Department of Energy and the CDC.

We acknowledge and thank all the operational staff and deployers at the CDC quarantine stations.

Note. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Data analyzed and presented in this report were deemed part of routine surveillance operations and granted a non-research determination in CDC review.

References

- 1.Kraemer MU, Yang CH, Gutierrez B, et al. The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science. 2020;368(6490):493–497. doi: 10.1126/science.abb4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Y, Hou S, Zhang Y, et al. Effect of travel restrictions of Wuhan city against COVID-19: a modified SEIR model analysis. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2022;16(4):1431–1437. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2021.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fareed Z, Ghaemi Asl M, Irfan M, et al. Exploring the co‐movements between COVID‐19 pandemic and international air traffic: a global perspective based on wavelet analysis. Int Migr. 2022 doi: 10.1111/imig.13026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J, Qin F, Qin X, et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 during air travel: a descriptive and modelling study. Ann Med. 2021;53(1):1569–1575. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2021.1973084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/quarantine-stations-us.html

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/contact-investigation.html

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/your-health/isolation.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fyour-health%2Fquarantine-isolation.html

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/fr-proof-negative-test.html

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/masks/mask-travel-guidance.html

- 11.Oliver S, Gargano J, Marin M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for use of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1922–1924. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6950e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]