Abstract

Aging is the largest risk factor for the development of cancer. A growing body of literature indicates that aging and cancer often play a somewhat reciprocal relationship at various times. On the one hand, aging is a “driver” of cancer, and on the other, cancer is a “disease driver” of aging. Here, we synthesize our reflections on the current literature linking cancer and aging, with an eye on fundamental aging processes, such as cellular senescence. Additionally, we consider how interventions that target fundamental aging processes can potentially transform cancer care, from preventing cancer development and progression to reducing the burden of accelerated aging in cancer survivors. Finally, we conclude with a reflection highlighting our vision for future directions to advance the science of cancer and aging and its applicability to improve the care of older adults with cancer.

Keywords: Aging, Aging biology, Cancer, Geroscience, Hallmarks

Aging and Cancer

Aging is the single greatest risk factor for developing cancer (1). Cancer and aging seem like opposite biological processes: cancer cells are characterized by a “gain of function and fitness” (2), whereas aging cells are characterized by a “loss of function and fitness” (3,4). Despite the seemingly opposite processes, there is a dynamic relationship between cancer and aging (5–7). On the one hand, aging is thought to be a “driver” of cancer (4), and on the other, cancer is a “disease driver” of aging (8). How do we reconcile these opposing yet interrelated processes?

This paper presents a perspective on the evolution of thinking about the relationship between aging and cancer over the more than 40 years of involvement by the senior author (H.J.C.) and the more recent involvement by the next generation of investigators working on this issue represented by the junior author (M.S.S.). As H.J.C. shifted his career from initial training in Hematology-Oncology to Geriatrics in the late 1970s (9), it seemed natural to begin to explore the then-understudied relationship of aging and cancer from a clinical perspective (10–13). With the publication of the article Aging and Neoplasia (14), followed by others (15,16), this began to evolve to consider how the fundamental biological processes might be related. Over the years, our understanding has further evolved to consider how aging and cancer often play a somewhat reciprocal relationship at various times (5–7). As H.J.C. and M.S.S. explored this further, the concept of an Aging–Cancer Cycle evolved (Figure 1). This article outlines our concept of this dynamic relationship as centered on fundamental aging processes.

Figure 1.

The Aging–Cancer Cycle. We conceptualize the dynamic relationship between aging and cancer as a cycle. Moving clockwise from aging (top) to cancer (bottom), we can see that aging is a “driver” of cancer. That is, fundamental aging processes (ie, the “hallmarks” or “pillars” of aging biology) contribute to both aging phenotypes (eg, frailty) and a protumorigenic environment that drives the emergence of many adult cancers. At the same time, cancer and its treatment can then be conceptualized as “disease drivers” of aging, moving clockwise from cancer (bottom) to aging (top). Both cancer and its treatments impact fundamental aging processes creating an accelerated aging state which creates an accelerated aging phenotypes in cancer survivors (eg, early-onset and increased prevalence of frailty). Hence, geroscience-guided interventions that target fundamental aging processes are well-poised to transform cancer care across the continuum, from prevention to survivorship.

Fundamental Aging Processes

Aging is a series of highly intertwined and interconnected fundamental processes termed the “hallmarks” or “pillars” of aging (3,4). These processes include genomic instability, proteostasis, inflammation, metabolism, macromolecular damage, stem cell/progenitor dysfunction, epigenetics, and cellular senescence (3,4). Evidence suggests that these fundamental aging processes are the core underlying mechanisms of how our bodies age.

Increasing evidence also suggests that fundamental aging processes may be modifiable. The Geroscience Hypothesis states that the basic biology of aging underlies the emergence of most chronic diseases, including cancer. Furthermore, the hypothesis suggests that interventions modifying this aging biology can delay or prevent the onset of such diseases (4,17). By targeting fundamental aging processes, geroscientists hypothesize that we can treat chronic disorders of aging as a group rather than tackle them one at a time. Multiple clinical trials are now underway to test if interventions targeting fundamental aging processes can delay or alleviate age-related disabilities and diseases (18–20). It is too early to know if these geroscience-guided interventions will be successful. But, if successful, the impact on clinical practice would be transformative, especially in cancer prevention and survivorship.

Aging: A Driver of Cancer

Despite variations in the biological drivers of cancer, most adult cancers increase in incidence with age (1). Indeed, the incidence curves for most adult cancers are strikingly similar, rising after the age of 50 years. This is not surprising; aging is driven by the accumulation of cellular damage and, in some respect, the hallmarks of aging (3,4) parallel the hallmarks of cancer (2).

Intrinsic cellular damage drives selection for mutations that facilitate a malignant phenotype. The cellular responses to accumulated mutations are complex, ranging from inflammation, suppression of growth or elimination of mutated cells, competitive interactions with neighboring normal cells, functional tissue decline, and in some cases, cancer (21,22). Age-associated mitochondrial dysfunction due to the accumulation of mutations within the mitochondrial genome also contributes to tumor growth and progression (23).

Beyond these intrinsic cellular changes, other fundamental aging processes, such as decreased immune regulation, are partly responsible for tumorigenesis (24). As we age, our immune system becomes less resilient and less efficient in detecting and fighting cancer cells (25). Studies in organisms ranging from flies to humans reveal that changes in immune regulation of the microenvironment facilitate cancer proliferation and drive metastasis (26).

One of the most important mechanisms linking cancer and aging is cellular senescence (27). Cellular senescence is a cell state where cells undergo terminal growth arrest (18). Senescent cells do not divide but are viable and remain metabolically active. A large number of senescent cells synthesize and secrete numerous factors, including proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors, collectively referred to as senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) (28).

Depending on the physiological context, senescent cells and downstream SASP can be beneficial or deleterious in the context of cancer. On the one hand, senescent cells and SASP suppress tumorigenesis, preventing the division of cells with oncogene activation or genetic instability and promoting the immune clearance of these cells (29,30). On the other hand, persistent senescent cells and SASP postcancer therapy can produce a tissue microenvironment that promotes relapse and metastasis (31,32). Hence, senescence is a “double-edged sword,” and further work is needed to understand when senescence is beneficial and when it is harmful.

Cancer: A Disease Driver of Aging

Cancer and its treatment can also be “disease drivers” of aging. In both older and younger adults, evidence demonstrates that cancer and its treatment increases the risk of developing decreased resilience, functional impairments, chronic diseases, and frailty–all signs of an accelerated aging state (33–36). Cancer survivors develop frailty twofold to fourfold more frequently and at an earlier age than age-matched individuals without cancer (37,38), and the prevalence rises to >40% in older survivors (39,40). By age 65, a cancer survivor, on average, also has >4 chronic conditions (41), suggesting an accelerated aging state (42,43).

The biological mechanisms that explain how cancer and its treatment exacerbate aging remain unknown. One thought is that cytotoxic and genotoxic cancer treatments accelerate fundamental aging processes (44). DNA-damaging chemotherapeutic agents, for example, induce cellular senescence (31). Senescent cells accumulate with age; chemotherapy and radiation also generate senescent cells. In mice, chemotherapy-induced senescent cells persist and contribute to local and systemic inflammation, as measured by increased SASP in tissue and sera (31). Eliminating senescent cells in these mice reduced SASP and reversed myelosuppression, cardiac dysfunction, and frailty.

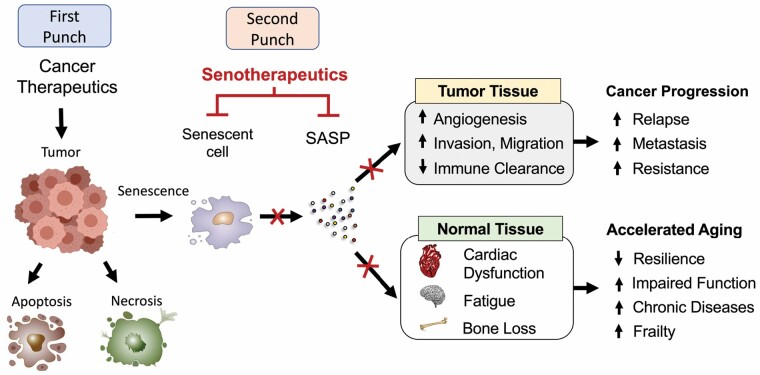

In recent years, 2 National Cancer Institute meetings (45,46) have proposed that clearing senescent cells after cancer treatment is a potential paradigm-shifting strategy to concurrently improve antitumor activity as well as mitigate accelerated aging. Given that senescent cells are only beneficial when they are transient, and the accumulation of senescent cells and SASP cause increased susceptibility to tumorigenesis, investigators have proposed the concept of combining senescence-inducing therapies and removal of senescent cells—the “one-two punch” model (Figure 2). The premise of the one–two punch is to first leverage the desired outcome of senescence then eliminate its detrimental effects. In this model, cancer treatments induce tumor cell senescence (first punch). After treatments are completed, pharmacological agents (senolytics) are introduced to selectively clear senescent cells in tumor and normal tissue (second punch). Interventions that clear senescent cells following cancer treatment are now being tested in trials in different cancer populations, including childhood cancer survivors (NCT04733534), hematopoietic cell transplant survivors (NCT02652052), and older breast cancer survivors (NCT05595499). Further work is warranted to understand how fundamental aging processes, like senescence, can be harnessed to transform cancer therapeutics and reduce the burden of accelerated aging in cancer survivors.

Figure 2.

“One–two punch” model: A senotherapy-mediated approach to cancer treatment. Anticancer therapeutics, such as chemotherapy or radiation, alter cellular states, including the induction of apoptosis, necrosis, and senescence, in cancer cells and tumor microenvironment. Therapy-induced senescent cells and downstream senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) in tumors are the desired outcome of anticancer treatment, halting tumor growth and stimulating immunosurveillance to eliminate tumor cells. However, the persistence of accumulated senescent cells and SASP postcancer treatment drives both tumor relapse and an accelerated aging state. To address these dual roles of senescence, experts have proposed the one–two punch model. In this model, cancer therapeutics (first punch) is followed by senotherapeutics (eg, senolytics or senomorphics) to clear persistent senescent cells and SASP (second punch), thus preventing tumor and normal tissue-related adverse effects. This strategy may yield a paradigm shift in the current clinical care of cancer survivors, especially older adults. However, key knowledge gaps remain in the discovery, development, and translation of senotherapeutics for clinical use in cancer treatment.

Thoughts on Future Directions

As we reflected further on H.J.C.’s long experience and, concurrently, with M.S.S.’ thinking about future approaches, together, we believe that there are several opportunities to advance the science of cancer and aging and its applicability to improve the care of older adults with cancer.

First, we need to break down the silos between aging and cancer researchers. To date, the researchers and clinicians in these 2 fields rarely interact. We need to bring together aging researchers who study the systemic and local impact of aging, including accelerated aging brought on by disease drivers, with cancer researchers who study the systemic and local aging environment that drives the emergence of cancer. By bringing these experts together to share their insight, we can begin to create a complete picture of how aging affects cancer (tumor initiation, progression, and recurrence) and how cancer affects aging (accelerated aging). Moreover, by bridging this gap, we can begin to create a complete picture of the potential therapeutic landscape and, ultimately, translate those advances to the clinic with the goal of reducing the morbidity and mortality of cancer. We applaud the recent efforts to do this, including the Keynote Symposia’s “Cancer: Aging in the Driver’s Seat” (R13CA257250) and the American Association for Cancer Research’s Conference “Aging and Cancer.” But this is just the beginning, and more funding and support is needed to foster discourse by international experts across both cancer and aging fields, from basic science to public health.

Second, we need to identify ways for aging and cancer researchers to work together. One potential common path is geroscience research. For example, an aging researcher may be studying the effects of exercise as an antiaging intervention (eg, how exercise affects fundamental aging processes to improve aging outcomes, such as physical function). Concurrently, a cancer researcher may be testing the effects of exercise as an anticancer intervention (eg, how exercise affect cancer biology to improve cancer outcomes, such as tumor recurrence). In this example, we would urge researchers to work together to examine the effects of exercise on fundamental processes that are shared by both cancer and aging. This concept would apply equally to other research, as noted later.

Finally, we envision that the relationship between cancer and aging is fertile ground for future exploration and will undoubtedly be the subject of multiple studies moving forward. Some of these studies might include: the application of geroscience to enhance the use of geriatric assessments to guide interventions; targeting biological aging to enhance treatment efficacy and postcancer therapy resilience; targeting biological aging to increase the immune response to cancer and to develop a better immune profile, or exploring new areas such as the importance of the microbiome, and the changes of aging in the microbiome as it relates to the prevention and treatment of cancer; or how age-related changes in metabolism impact the aging–cancer relationship. Clearly, many aspects of the interplay between cancer and aging need additional research. We are excited about the emerging tools of modern biology, including single-cell and systems biology and artificial intelligence, which we believe will make it easier to obtain deep insights into this complex interplay, and undoubtedly lead to more efficacious interventions to improve the care of older adults with cancer in the future.

Conclusion

In summary, the proposed Aging–Cancer Cycle provides one way of thinking about the mutual impact of “Aging on Cancer” and “Cancer on Aging” and why it is important to study both further. We believe that a central premise to advancing both fields is to dive deeper into the underlying biology of aging. Understanding the impact of fundamental aging processes on cancer emergence may inform cancer prevention. On the other hand, understanding the impact of cancer on accelerating aging can inform approaches to preserving health during and after cancer treatment. With the population aging, greater use of early detection, and advances in treatment, the number of older adults diagnosed with and surviving from cancer is dramatically increasing. Yet, the evidence base for treating this population is sparse. As a result, geriatricians, internists, and oncologists will be challenged to address the health issues facing older adults with cancer. Thus, investigating the relationship between aging biology and cancer should be a central pillar of research for both oncology and geriatrics.

Contributor Information

Mina S Sedrak, Department of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics Research, City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, California, USA.

Harvey Jay Cohen, Department of Medicine, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Funding

Support in part by the National Institute on Aging R03 AG064377 (M.S.S.), K76 AG074918 (M.S.S.), and P30 AG028716 (H.J.C.); and the National Cancer Institute R21 CA277660 (M.S.S.).

Role of the Funder

The funders had no role in the writing of the manuscript and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Contributions

Manuscript preparation (M.S.S. and H.J.C.). Manuscript editing and review (M.S.S. and H.J.C.). All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:1029–1036. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kennedy BK, Berger SL, Brunet A, et al. Geroscience: linking aging to chronic disease. Cell. 2014;159:709–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aunan JR, Cho WC, Søreide K. The biology of aging and cancer: a brief overview of shared and divergent molecular hallmarks. Aging Dis. 2017;8:628–642. doi: 10.14336/AD.2017.0103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berben L, Floris G, Wildiers H, Hatse S. Cancer and aging: two tightly interconnected biological processes. Cancers. 2021;13:1400. doi: 10.3390/cancers13061400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blagosklonny MV. Hallmarks of cancer and hallmarks of aging. Aging 2022;14:4176–4187. doi: 10.18632/aging.204082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hodes RJ, Sierra F, Austad SN, et al. Disease drivers of aging: disease drivers of aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1386:45–68. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cohen HJ. An accidental career in geriatrics. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:1945–1948. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen HJ, Silberman HR, Forman W, Bartolucci A, Liu C, For the Southeastern Cancer Cooperative Study Group. Effects of age on responses to treatment and survival of patients with multiple myeloma. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983;31:272–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1983.tb04870.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. DeMaria LC, Cohen HJ.. Comprehensive cancer care, special problems of the elderly. In: Laszlo J, ed. A Physicians Guide to Cancer Care Complications; Prevention and Management. Marcel Dekker Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Allen C, Cox EB, Manton KG, Cohen HJ. Breast cancer in the elderly: current patterns of care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34:637–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1986.tb04904.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DeMaria LC, Cohen HJ. Characteristics of lung cancer in elderly patients. J Gerontol. 1987;42:540–545. doi: 10.1093/geronj/42.5.540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crawford J, Cohen HJ. Aging and neoplasia. Annu Rev Gerontol Geriatr. 1984;4:3–32. doi: 10.1891/0198-8794.4.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Crawford J, Cohen HJ. Relationship of cancer and aging. Clin Geriatr Med. 1987;3:419–432. doi: 10.1016/S0749-0690(18)30791-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cohen HJ. Biology of aging as related to cancer. Cancer. 1994;74:2092–2100. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sierra F, Caspi A, Fortinsky RH, et al. Moving geroscience from the bench to clinical care and health policy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:2455–2463. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kirkland JL, Tchkonia T. Senolytic drugs: from discovery to translation. J Intern Med. 2020;288:518–536. doi: 10.1111/joim.13141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hickson LJ, Langhi Prata LGP, Bobart SA, et al. Senolytics decrease senescent cells in humans: preliminary report from a clinical trial of Dasatinib plus Quercetin in individuals with diabetic kidney disease. EBioMedicine. 2019;47:446–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.08.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Justice JN, Nambiar AM, Tchkonia T, et al. Senolytics in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: results from a first-in-human, open-label, pilot study. EBioMedicine. 2019;40:554–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.12.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Laconi E, Marongiu F, DeGregori J. Cancer as a disease of old age: changing mutational and microenvironmental landscapes. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:943–952. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0721-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marongiu F, DeGregori J. The sculpting of somatic mutational landscapes by evolutionary forces and their impacts on aging-related disease. Mol Oncol. 2022;16:3238–3258. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.13275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith ALM, Whitehall JC, Greaves LC. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in ageing and cancer. Mol Oncol. 2022;16:3276–3294. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.13291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Disis ML. Immune regulation of cancer. JCO. 2010;28:4531–4538. doi: 10.1200/jco.2009.27.2146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gonzalez H, Hagerling C, Werb Z. Roles of the immune system in cancer: from tumor initiation to metastatic progression. Genes Dev. 2018;32:1267–1284. doi: 10.1101/gad.314617.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Havas A, Yin S, Adams PD. The role of aging in cancer. Mol Oncol. 2022;16:3213–3219. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.13302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Campisi J. Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:685–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coppé J-P, Desprez P-Y, Krtolica A, Campisi J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: the dark side of tumor suppression. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2010;5:99–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marin I, Boix O, Garcia-Garijo A, et al. Cellular senescence is immunogenic and promotes anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Discov. 2022:CD-22-0523. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-22-0523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen H-A, Ho Y-J, Mezzadra R, et al. Senescence rewires microenvironment sensing to facilitate anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Discov. 2022:CD-22-0528. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-22-0528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Demaria M, O’Leary MN, Chang J, et al. Cellular senescence promotes adverse effects of chemotherapy and cancer relapse. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:165–176. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang B, Kohli J, Demaria M. Senescent cells in cancer therapy: friends or foes? Trends Cancer. 2020;6:838–857. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2020.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hurria A, Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Allred JB, et al. Functional decline and resilience in older women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:920–927. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mandelblatt JS, Zhou X, Small BJ, et al. Deficit accumulation frailty trajectories of older breast cancer survivors and non-cancer controls: the thinking and living with cancer study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:1053–1064. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carroll JE, Bower JE, Ganz PA. Cancer-related accelerated ageing and biobehavioural modifiers: a framework for research and clinical care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:173–187. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00580-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sedrak MS, Gilmore NJ, Carroll JE, Muss HB, Cohen HJ, Dale W. Measuring biologic resilience in older cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol.. 2021;39:2079–2089. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Henderson TO, Ness KK, Cohen HJ. Accelerated aging among cancer survivors: from pediatrics to geriatrics. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2014;34:e423–e430. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2014.34.e423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Guida JL, Ahles TA, Belsky D, et al. Measuring aging and identifying aging phenotypes in cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:1245–1254. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Handforth C, Clegg A, Young C, et al. The prevalence and outcomes of frailty in older cancer patients: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1091–1101. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hoogendijk EO, Afilalo J, Ensrud KE, Kowal P, Onder G, Fried LP. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet. 2019;394:1365–1375. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31786-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Guy GP, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, Rim SH, Li R, Richardson LC. Economic burden of chronic conditions among survivors of cancer in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2053–2061. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.9716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sedrak MS, Kirkland JL, Tchkonia T, Kuchel GA. Accelerated aging in older cancer survivors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:3077–3080 . doi: 10.1111/jgs.17461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mandelblatt JS, Ahles TA, Lippman ME, et al. Applying a life course biological age framework to improving the care of individuals with adult cancers: review and research recommendations. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(11):1692–1699. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cupit-Link MC, Kirkland JL, Ness KK, et al. Biology of premature ageing in survivors of cancer. ESMO Open. 2017;2:e000250. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Prasanna PG, Citrin DE, Hildesheim J, et al. Therapy-induced senescence: opportunities to improve anticancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(10):1285–1298. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Guida JL, Agurs-Collins T, Ahles TA, et al. Strategies to prevent or remediate cancer and treatment-related aging. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:112–122. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]