To the Editor:

The incidence of skin cancers, especially melanoma, continues to rise, particularly among adolescents and young adults.1–3 Ultraviolet (UV) exposure from tanning (outdoor tanning [OT] and indoor tanning [IT]) is a major, modifiable risk factor.4,5 Although many studies have examined the prevalence of individual tanning modalities, little is known about how people combine tanning modalities. Combination tanning may be associated with higher cumulative UV exposure than single-modality tanning and, therefore, higher risk for skin cancer. Interventions focusing on a single modality without acknowledging sequential or concurrent use of other tanning modalities may not effectively reduce total UV exposure. The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of combination tanning among undergraduates at a southeastern university and identify characteristics distinguishing combination tanners from single-modality tanners.

Surveys were e-mailed to all undergraduates at a public state university in Alabama in March 2016. This survey had previously been approved by the University of South Alabama Institutional Review Board (protocol number #854018-1). Primary outcome measures were self-reported current OT and/or ever use of (1) IT and/or (2) spray tanning [ST]. Combination tanners were defined by use of 2 or more tanning modalities. Descriptive measures included demographics, Fitzpatrick skin type, attitudinal variables, and risk perceptions. Logistic and stepwise regressions were used to examine relationships between descriptive measures and tanning behaviors.

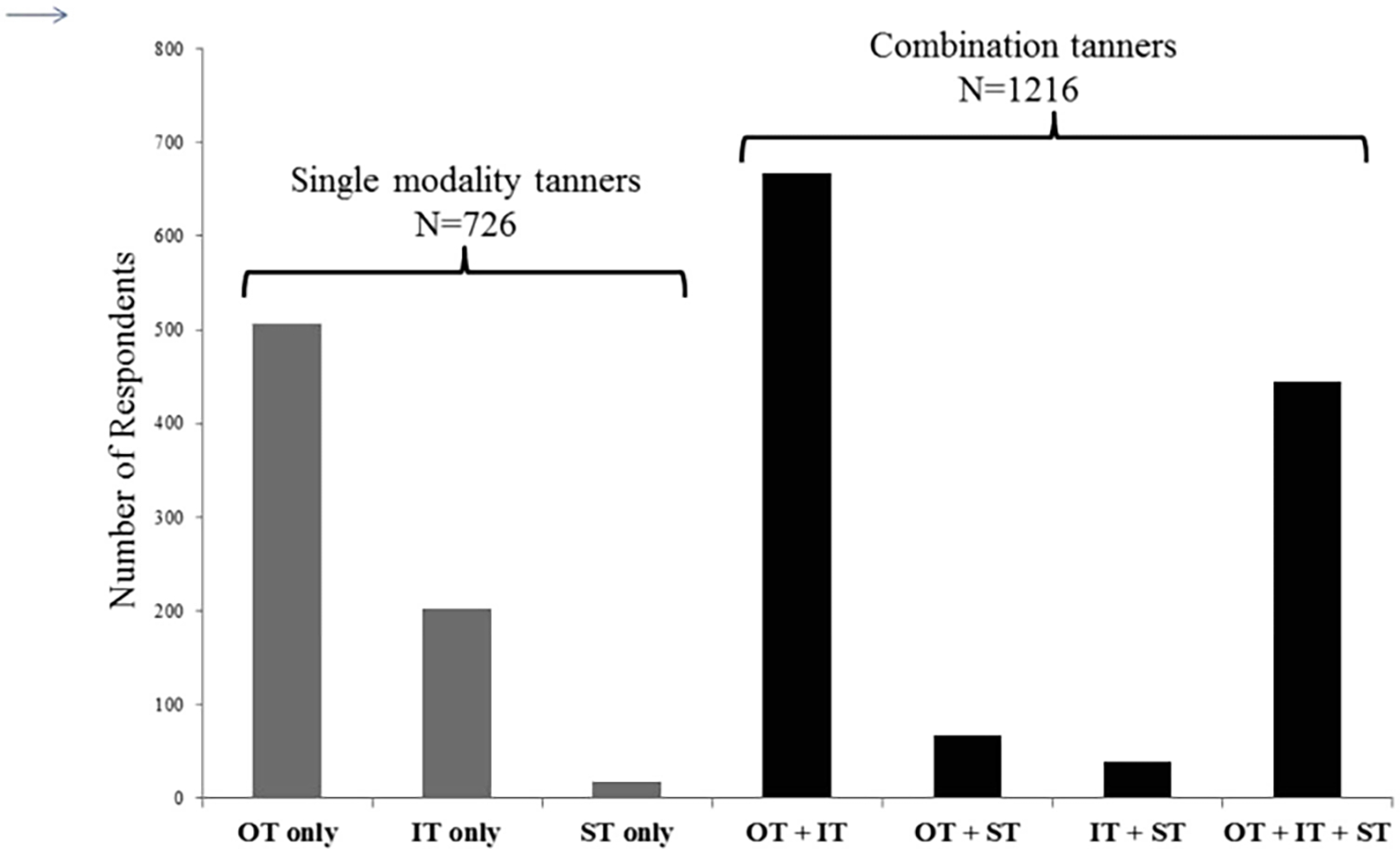

Of the 2587 respondents (25% response rate), 1942 reported at least 1 tanning behavior, thus comprising the study population. The majority were female (73.2%), white (80.0%), and residents of Alabama (78.5%). Use of only 1 tanning modality was reported by 726 respondents (37.3% [termed single-modality tanners]), whereas 1216 respondents reported using/having used more than 1 tanning modality (62.7% [termed combination tanners]) (Fig 1). Among combination tanners, OT plus IT were used by 667 (54.9%), with OT plus IT plus ST used by 444 (36.5%). Therefore, both UV-based tanning modalities (OT + IT), with or without ST, were used by 91.4% of combination tanners.

Fig 1.

Single-modality versus combination tanning. Frequency histogram of the study population (N = 1942). Gray bars represent single-modality tanners, black bars represent combination tanners. Of the single-modality tanners, 506 (69.7%) reported outdoor tanning (OT), 203 (28.0%) reported indoor tanning (IT), and 17 (2.3%) reported spray tanning (ST). Among combination tanners, the majority reported OT + IT (667 [54.9%]). OT + ST was used by 66 (5.4%), whereas IT + ST was used by 39 (3.2%). Of the combination tanners, 444 (36.5%) reported using all 3 tanning modalities (OT + IT + ST).

In the multivariate analysis (Table I), females were more than 3 times as likely as males to be combination tanners (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 3.75; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.88–4.88; P < .0001). African Americans were least likely to combination tan (AOR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.12–0.33; P < .0001). Residents of Alabama were 50% more likely to be combination tanners than students from other states (AOR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.14–1.97; P < .01). Increasing college year demonstrated a progressively greater likelihood of combination tanning. Intention to practice IT within the next 12 months demonstrated the greatest association with combination tanning (AOR, 23.72; 95% CI, 11.89–47.33; P < .0001) despite combination tanners being more likely than single-modality tanners to be informed about risks of IT (AOR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.11–2.37; P = .01).

Table I.

Final multivariate model of variables associated with combination tanning vs. single-modality tanning

| Variable | Single-modality tanners (n = 726) | Combination tanners (n = 1216) | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Male (ref) | 294 (40.5) | 221 (18.2) | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 431 (59.5) | 991 (81.8) | 3.75 | 2.88–4.88 | <.0001 |

| Race | |||||

| White (ref) | 496 (68.3) | 1057 (86.9) | 1.00 | ||

| Black or African American | 109 (15) | 42 (3.5) | 0.20 | 0.12–0.33 | <.0001 |

| Other | 121 (16.7) | 117 (9.6) | 0.59 | 0.41–0.84 | <.01 |

| Alabama resident | |||||

| No (ref) | 174 (24.0) | 240 (19.8) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 551 (76.0) | 974 (80.2) | 1.50 | 1.14–1.97 | <.01 |

| Fitzpatrick skin type | |||||

| I + II | 111 (15.3) | 179 (14.7) | 0.92 | 0.60–1.43 | .72 |

| III | 200 (27.5) | 459 (37.8) | 1.33 | 0.91–1.95 | .15 |

| IV | 245 (33.8) | 421 (34.6) | 1.18 | 0.83–1.68 | .35 |

| V + VI (ref) | 170 (23.4) | 157 (12.9) | 1.00 | ||

| Family history of melanoma | |||||

| No (ref) | 523 (72.0) | 939 (77.2) | |||

| Yes | 55 (7.6) | 104 (8.6) | 0.71 | 0.47–1.09 | .10 |

| Don’t know/not sure | 148 (20.4) | 173 (14.2) | 0.56 | 0.41–0.76 | <.001 |

| College year | |||||

| Freshman (ref) | 175 (24.1) | 198 (16.3) | 1.00 | ||

| Sophomore | 157 (21.6) | 256 (21.0) | 1.64 | 1.17–2.36 | <.01 |

| Junior | 203 (28.0) | 337 (27.7) | 1.70 | 1.21–2.37 | <.01 |

| Senior | 191 (26.3) | 425 (35.0) | 2.57 | 1.85–3.58 | <.0001 |

| Intend to tan indoors within the next 12 months | |||||

| No (ref) | 717 (98.2) | 789 (64.9) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 9 (1.2) | 427 (35.1) | 23.72 | 11.89–47.33 | <.0001 |

| Ever seen/heard about risks of tanning beds | |||||

| No (ref) | 119 (16.4) | 81 (6.7) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 605 (83.6) | 1132 (93.3) | 1.62 | 1.11–2.37 | .01 |

| Looks better to be tan than pale | |||||

| Strongly agree | 69 (9.5) | 294 (24.2) | 3.48 | 1.84–6.58 | <.0001 |

| Agree | 269 (37.2) | 524 (43.1) | 2.30 | 1.30–4.08 | <.01 |

| Neutral | 255 (35.2) | 273 (22.5) | 1.55 | 0.87–2.78 | .14 |

| Disagree | 83 (11.5) | 96 (7.9) | 1.75 | 0.93–3.29 | .08 |

| Strongly disagree (ref) | 48 (6.6) | 28 (2.3) | 1.00 | ||

| Using a tanning bed is fine if not too frequent | |||||

| Strongly agree | 17 (2.3) | 85 (7.0) | 6.44 | 3.00–13.85 | <.0001 |

| Agree | 155 (21.4) | 408 (33.7) | 2.49 | 1.71–3.61 | <.0001 |

| Neutral | 202 (27.9) | 317 (26.2) | 1.82 | 1.28–2.57 | <.001 |

| Disagree | 203 (28.0) | 267 (22.1) | 1.38 | 0.99–1.93 | .06 |

| Strongly disagree (ref) | 148 (20.4) | 134 (11.1) | 1.00 | ||

ref, Reference.

In this large independent tanning survey of undergraduates, we found pervasive use of multiple tanning modalities. This is especially concerning because of the high frequency of combining OT with IT. Given that only current OT was assessed, cumulative lifetime recreational UV exposure may be higher. Further study is warranted to confirm these findings and investigate how combination tanning affects skin cancer risk.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lazovich D, Isaksson Vogel R, Weinstock MA, et al. Association between indoor tanning and melanoma in younger men and women. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(3):268–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong BK, Kricker A. The epidemiology of UV induced skin cancer. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2001;63(1–3):8–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Autier P, Dore JF. Influence of sun exposures during childhood and during adulthood on melanoma risk. EPIMEL and EORTC Melanoma Cooperative Group. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Int J Cancer. 1998;77(4):533–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazovich D, Vogel RI, Berwick M, et al. Indoor tanning and risk of melanoma: a case-control study in a highly exposed population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(6):1557–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]