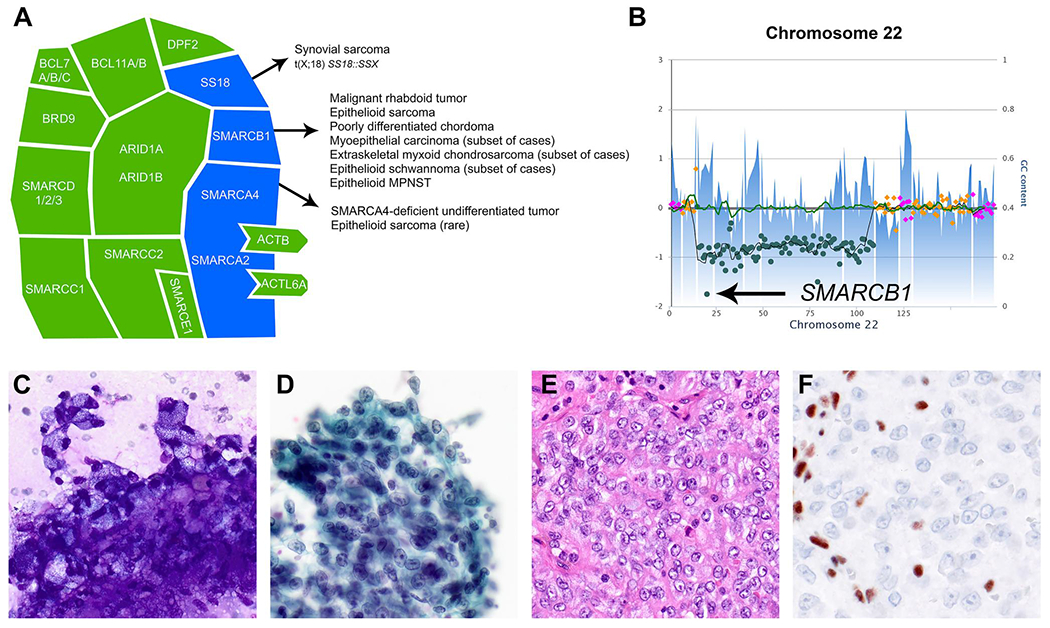

The mammalian switch sucrose non-fermentable (SWI/SNF) chromatin remodeling complex, also known as the BRG1/BRM-associated factor (BAF) complex, is a key epigenetic modifier that orchestrates chromatin compaction and accessibility for gene transcription in an adenosine triphosphate–dependent manner.1 It thereby enables DNA replication and accessibility for selective gene transcription, DNA repair, and recombination.1 The SWI/SNF complex is a large, multi-unit protein assembly with a molecular weight of ~2 MDa, and it is composed of 10–15 highly conserved subunits bound together among a set of more than 20 possible units, which are encoded by 29 genes (Figure 1A).1

FIGURE 1.

(A) The mammalian SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex. This schematic illustrates the assembly of 15 subunits encoded by 29 genes. Key subunits frequently dysregulated in soft tissue neoplasms are highlighted in blue. Adapted from Kadoch et al.1 and Schaefer et al.4 (B–F) A representative case of an epithelioid MPNST showing (B) homozygous deletion of SMARCB1 on chromosome 22q (arrow) and (C,D) epithelioid tumor cells in clusters embedded in a myxoid–fibrillary matrix with prominent nucleoli and prominent cytoplasmic vacuolization on fine-needle aspiration smears ([C] modified Romanowsky stain and [D] Papanicolaou stain, ×400). (E) A corresponding cell block reveals epithelioid tumor cells arranged in sheets and lobules and displays eosinophilic cytoplasm and round to ovoid nuclei with prominent nucleoli and frequent mitoses (H & E stain, ×400). (F) Expression of SMARCB1 is lost in tumor cells (immunohistochemistry, ×400). GC indicates guanine or cytosine; MPNST, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor; SWI/SNF, switch sucrose non-fermentable.

More than 20% of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies in children and adults are characterized by SWI/SNF complex deficiency.2,3 Mutational events target distinct subunits in a cancer-specific fashion, and this indicates tissue-specific protective roles.1 These events can be heterozygous or homozygous, occur in a germline or somatic context, and include point mutations, deletions, and translocations; they reflect a wide range of biological functions depending on the disease context. SWI/SNF complex dysregulation in cancer can lead to either loss-of-function of tumor suppressors and/or gain-of-function of oncogenic mechanisms.1

SWI/SNF complex inactivation in mesenchymal neoplasms

SWI/SNF-deficient soft tissue neoplasms comprise malignant rhabdoid tumor as the prototypical example of a SWI/SNF-deficient tumor, epithelioid sarcoma, poorly differentiated chordoma, myoepithelial carcinoma, extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma, epithelioid schwannoma, and epithelioid malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (Table 1, Figure 1B–F).4 The SMARCB1 (INI1, BAF47, hSNF5) core subunit encoded by SMARCB1 on 22q11.23 is the subunit most frequently inactivated in soft tissue tumors. The hallmark of SS18::SSX gene fusion, characteristic of synovial sarcoma, represents a mechanism of indirectly inactivating SMARCB1 function.5,6 SMARCA4 (BRG1) loss is uniformly found in SMARCA4-deficient undifferentiated thoracic tumors (SMARCA4-DUTs), which were previously known as SMARCA4-deficient thoracic sarcomas. It also occurs as an alternative event in mesenchymal tumors lacking canonical SMARCB1 loss (Figure 1A).

TABLE 1.

Overview of selected neoplasms with SWI/SNF complex deficiency.

| Tumor | Age and sex distribution | Anatomic predilection | SWI/SNF subunit genomic inactivation | SWI/SNF subunit protein deficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malignant rhabdoid tumor | Infants and children, F = M | Kidney, brain, soft tissue | SMARCB1 (95%) | 100% |

| SMARCA4 (<5%) | ||||

| Epithelioid sarcoma | Mostly young adults, M > F | Trunk, distal extremities | SMARCB1 | 90% |

| Poorly differentiated chordoma | Mostly children, F > M | Skull base/clivus, axial spine | SMARCB1 | 100 |

| Myoepithelial carcinoma | Children and adults, M > F | Extremities, limb girdle | SMARCB1 | 10%–40% |

| Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma | Mostly adults, M > F | Extremities, limb girdle | SMARCB1 | 17% |

| Epithelioid schwannoma | Mostly adults, F = M | Trunk, extremities | SMARCB1 | 40% |

| Epithelioid MPNST | Mostly adults, F = M | Trunk, extremities | SMARCB1 | 70% |

| SMARCA4-deficient undifferentiated thoracic tumor | Mostly adults, M > F | Mediastinum, pleura, lung | SMARCA4 | SMARCA4 (100%), SMARCA2 (100%) |

Note: This table has been adapted from Schaefer et al.4

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male; MPNST, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor; SWI/SNF, switch sucrose non-fermentable.

Regardless of the tumor type and the site of origin, most SWI/SNF-deficient neoplasms share common histopathologic features, including an undifferentiated large epithelioid cell or “rhabdoid” cytomorphology, which is defined by eccentric vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli and glassy eosinophilic, inclusion-like cytoplasmic structures. These characteristic morphologic features can be very helpful in the diagnostic workup of neoplasms with an undifferentiated epithelioid (and epithelial) morphology and guide ancillary immunohistochemical staining for SWI/SNF subunit deficiency, especially in the setting of small-volume biopsies.7,8 The presence of universal monotonous undifferentiated cytomorphology in SWI/SNF-deficient neoplasms has been attributed to its roles in coordinating cellular differentiation and proliferation, so that SWI/SNF complex inactivation may result in an undifferentiated cellular state.9

The highest frequencies of SMARCB1 inactivation are found in malignant rhabdoid tumors, epithelioid sarcoma, and poorly differentiated chordoma (Table 1), in which SMARCB1 inactivation is considered to be the driving event. Malignant rhabdoid tumors are rare, highly aggressive neoplasms virtually always affecting infants and young children, and they are characterized by SMARCB1 biallelic inactivation through various mechanisms in virtually all cases.10–12 SMARCB1 germline abnormalities were initially discovered in subsets of patients with malignant rhabdoid tumors and enabled the very first insights into the tumor suppressor roles of SMARCB1 tumors.11–13

Epithelioid sarcoma affects young adults with a slight male predominance. It occurs mostly in the superficial soft tissue of the distal extremities (the conventional type) or in the deep soft tissue of the truncal regions (the proximal type). Both subtypes of epithelioid sarcoma harbor SMARCB1 genomic inactivation through homozygous deletion in 75% of cases14 and show SMARCB1 protein loss in 90% of cases.15,16 Other mechanisms of SMARCB1 inactivation include heterozygous intragenic deletions and loss-of-function mutations. In rare instances, SMARCB1 expression is retained, and epithelioid sarcomas have been reported to show loss of other SWI/SNF subunits such as SMARCA4, SMARCC2, and SMARCC1.17

Poorly differentiated chordoma is an extremely rare subtype of chordoma that occurs mostly in children and behaves more aggressively than conventional chordoma.18 This subtype is characterized by distinct histologic features, such as sheetlike growth with limited stroma and tumor cells with vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and frequent mitotic figures.19 Virtually all cases of poorly differentiated chordoma show SMARCB1 loss—usually caused by homozygous deletions20,21—whereas SMARCB1 is retained in conventional chordoma.18

SWI/SNF complex inactivation in nonmesenchymal neoplasms

Among all cancer types, ARID1A, which interacts with DNA to facilitate SWI/SNF binding to target sites, is the most frequently dysregulated SWI/SNF subunit.22 ARID1A mutations have been identified in many different tumor types, such as endometrioid and clear cell ovarian carcinomas (~45%), gastric and bladder cancer (~20%), hepatocellular carcinoma (~14%), colorectal cancer and melanoma (~10%), and lung, pancreatic, and breast cancers (less frequently)3 as well as pediatric neuroblastoma23 and dedifferentiated meningioma.24 Other genomically inactivated genes encoding the SWI/SNF subunit are SMARCA4, SMARCA2, ARID1A, ARID1B, ARID2, and PBRM1. Specifically, inactivation of SMARCA4, SMARCA2, or SMARCB1 has been reported in non–small cell lung cancer,25–27 undifferentiated/rhabdoid carcinomas (gastrointestinal,28 urothelial tract,29 and uterine30), and several sinonasal malignancies.31,32 In many undifferentiated carcinomas, SWI/SNF perturbations represent passenger mutations and not necessarily driver events in a complex genomic landscape.

Notably, thoracic SMARCA4-DUT (also known as SMARCA4-deficient thoracic sarcoma) is recognized as a high-grade, smoking-related sarcomatoid/undifferentiated carcinoma33 in the 2021 World Health Organization classification of thoracic tumors.34,35 In contrast to SMARCA4-deficient non–small cell lung carcinoma, SMARCA4-DUT shows prominent mediastinal involvement, undifferentiated large epithelioid or rhabdoid cytomorphology with co-inactivation of SMARCA2 (BRM), and a typical immunophenotypical signature of co-expression of SOX2 and SALL4, with a lack of claudin 4 in addition to loss of combined SMARCA4 and SMARCA2 expression.36 Similarly seen in the majority of cases of small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type, a rare and aggressive cancer in adolescents and young women, biallelic inactivation of SMARCA4 serves as the driver event in the pathogenesis of SMARCA4-DUT, often in association with epigenetic SMARCA2 loss.36 In recent years, many other SMARCA4-deficient tumors of epithelial, mesenchymal, or uncertain lineages have been described in the central nerve system, the head and neck, and various visceral organs as well as the skin.36,37

Therapeutic strategies targeting SWI/SNF-deficient neoplasms

Recent preclinical research advances led to Food and Drug Administration approval of the first EZH2 inhibitor, tazemetostat, in January 2020 for the treatment of patients aged ≥16 years with locally advanced or metastatic epithelioid sarcoma not eligible for complete resection.38–40 The premise for this work is the fact of functional antagonism of the SWI/SNF and PRC2 complexes.41,42 Studies of SMARCB1-deficient malignant rhabdoid tumors43–45 and epithelioid sarcomas46 demonstrated early antiproliferative effects of therapeutic EZH2 inhibition with durable responses. A protein degrader of BRD9 is currently under clinical investigation for patients with synovial sarcoma (NCT04965753). In addition, immune checkpoint inhibition therapy has shown promising outcomes in managing patients with advanced stages of subsets of SWI/SNF-deficient malignancies.47 Future studies are expected to lead to refined therapeutic strategies for neoplasms with canonical SWI/SNF complex perturbation.

In conclusion, perturbations of the SWI/SNF complex are identified in a significant subset of human cancers, including a wide range of mesenchymal and nonmesenchymal neoplasms affecting both children and adults. Because most patients with SW1/SNF-deficient tumors pursue an aggressive clinical course and present at advanced stages, recognizing these tumors on small biopsies, including fine-needle aspiration and cytology specimens, is crucial for establishing a refined diagnosis for these patients.7,48,49 These tumors share common undifferentiated “rhabdoid” appearances, which represent a helpful clue in their diagnostic workup. Novel therapeutic approaches are being developed for a variety of malignancies unified by SWI/SNF deficiency, and ongoing translational research efforts are expected to further expand mechanistic insights into the complex biology of the SWI/SNF complex and its key roles in human cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by the National Cancer Institute (grant K08CA241085 to Inga-Marie Schaefer).

Biographies

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES

Inga-Marie Schaefer is an assistant professor of pathology at Harvard Medical School and an associate pathologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. She is also an associate member of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. Dr Schaefer trained in anatomic pathology at the University Hospital Göttingen in Germany and at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. In 2018, she obtained board certification in anatomic pathology and became faculty in the Department of Pathology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Dr Schaefer leads a research program centered on the biology, genetics, and molecular mechanisms of sarcomas with the goal of developing novel therapeutics.

Xiaohua Qian is a clinical professor of pathology at Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, California. She practices cytopathology and bone and soft tissue pathology. She was previously the director of the fine-needle aspiration clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts), where she completed a residency in anatomic pathology and a fellowship in cytopathology.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Inga-Marie Schaefer, assistant professor of pathology at Harvard Medical School and an associate pathologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Xiaohua Qian, clinical professor of pathology at Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, California.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kadoch C, Crabtree GR. Mammalian SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complexes and cancer: mechanistic insights gained from human genomics. Sci Adv. 2015;1(5):e1500447. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.l500447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shain AH, Pollack JR. The spectrum of SWI/SNF mutations, ubiquitous in human cancers. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e55119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kadoch C, Hargreaves DC, Hodges C, et al. Proteomic and bioinformatic analysis of mammalian SWI/SNF complexes identifies extensive roles in human malignancy. Not Genet. 2013;45(6):592–601. doi: 10.1038/ng.2628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaefer IM, Hornick JL. SWI/SNF complex–deficient soft tissue neoplasms: an update. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2021;38(3):222–231. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2020.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McBride MJ, Pulice JL, Beird HC, et al. The SS18–SSX fusion oncoprotein hijacks BAF complex targeting and function to drive synovial sarcoma. Cancer Cell. 2018;33(6):1128–1141.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kadoch C, Crabtree GR. Reversible disruption of mSWI/SNF (BAF) complexes by the SS18–SSX oncogenic fusion in synovial sarcoma. Cell. 2013;153(1):71–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaefer IM, Al-Ibraheemi A, Qian X. Cytomorphologic spectrum of SMARCB1-deficient soft tissue neoplasms. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;156(2):229–245. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeda M, Tani Y, Saijo N, et al. Cytopathological features of SMARCA4-deficient thoracic sarcoma: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Int J Surg Pathol. 2020;28(1):109–114. doi: 10.1177/1066896919870866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agaimy A SWI/SNF complex–deficient soft tissue neoplasms: a pattern-based approach to diagnosis and differential diagnosis. Surg Pathol Clin. 2019;12(1):149–163. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2018.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Versteege I, Sevenet N, Lange J, et al. Truncating mutations of hSNF5/INI1 in aggressive paediatric cancer. Nature. 1998;394(6689):203–206. doi: 10.1038/28212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eaton KW, Tooke LS, Wainwright LM, Judkins AR, Biegel JA. Spectrum of SMARCB1/INI1 mutations in familial and sporadic rhabdoid tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(1):7–15. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biegel JA, Fogelgren B, Wainwright LM, Zhou JY, Bevan H, Rorke LB. Germline INI1 mutation in a patient with a central nervous system atypical teratoid tumor and renal rhabdoid tumor. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;28(1):31–37. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biegel JA, Busse TM, Weissman BE. SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complexes and cancer. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2014;166C(3):350–366. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dermawan JK, Singer S, Tap WD, et al. The genetic landscape of SMARCB1 alterations in SMARCB1-deficient spectrum of mesenchymal neoplasms. Mod Pathol. 2022;35(12):1900–1909. doi: 10.1038/s41379-022-01148-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Loarer F, Zhang L, Fletcher CD, et al. Consistent SMARCB1 homozygous deletions in epithelioid sarcoma and in a subset of myoepithelial carcinomas can be reliably detected by FISH in archival material. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2014;53(6):475–486. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hornick JL, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CD. Loss of INI1 expression is characteristic of both conventional and proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(4):542–550. doi: 10.1097/pas.0b013e3181882c54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohashi K, Yamamoto H, Yamada Y, et al. SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex status in SMARCB1/INI1-preserved epithelioid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(3):312–318. doi: 10.1097/pas.0000000000001011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shih AR, Cote GM, Chebib I, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of poorly differentiated chordoma. Mod Pathol. 2018;31(8):1237–1245. doi: 10.1038/s41379-018-0002-l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoch BL, Nielsen GP, Liebsch NJ, Rosenberg AE. Base of skull chordomas in children and adolescents: a clinicopathologic study of 73 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30(7):811–818. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000209828.39477.ab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owosho AA, Zhang L, Rosenblum MK, Antonescu CR. High sensitivity of FISH analysis in detecting homozygous SMARCB1 deletions in poorly differentiated chordoma: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of nine cases. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2018;57(2):89–95. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shih AR, Chebib I, Deshpande V, Dickson BC, Iafrate AJ, Nielsen GP. Molecular characteristics of poorly differentiated chordoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2019;58(11):804–808. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chandler RL, Brennan J, Schisler JC, Serber D, Patterson C, Magnuson T. ARID1a-DNA interactions are required for promoter occupancy by SWI/SNF. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33(2):265–280. doi: 10.1128/mcb.01008-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sausen M, Leary RJ, Jones S, et al. Integrated genomic analyses identify ARID1A and ARID1B alterations in the childhood cancer neuroblastoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45(1):12–17. doi: 10.1038/ng.2493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abedalthagafi MS, Bi WL, Merrill PH, et al. ARID1A and TERT promoter mutations in dedifferentiated meningioma. Cancer Genet. 2015;208(6):345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2015.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xue Y, Meehan B, Fu Z, et al. SMARCA4 loss is synthetic lethal with CDK4/6 inhibition in non–small cell lung cancer. Not Commun. 2019;10(1):557. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08380-l [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agaimy A, Fuchs F, Moskalev EA, Sirbu H, Hartmann A, Haller F. SMARCA4-deficient pulmonary adenocarcinoma: clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, and molecular characteristics of a novel aggressive neoplasm with a consistent TTF1(neg)/CK7(pos)/HepPar1(pos) immunophenotype. Virchows Arch. 2017;471(5):599–609. doi: 10.1007/s00428-017-2148-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herpel E, Rieker RJ, Dienemann H, et al. SMARCA4 and SMARCA2 deficiency in non–small cell lung cancer: immunohistochemical survey of 316 consecutive specimens. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2017;26:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2016.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agaimy A, Daum O, Markl B, Lichtmannegger I, Michal M, Hartmann A. SWI/SNF complex-deficient undifferentiated/rhabdoid carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract: a series of 13 cases highlighting mutually exclusive loss of SMARCA4 and SMARCA2 and frequent co-inactivation of SMARCB1 and SMARCA2. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(4):544–553. doi: 10.1097/pas.0000000000000554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agaimy A, Bertz S, Cheng L, et al. Loss of expression of the SWI/SNF complex is a frequent event in undifferentiated/dedifferentiated urothelial carcinoma of the urinary tract. Virchows Arch. 2016;469(3):321–330. doi: 10.1007/s00428-016-1977-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strehl JD, Wachter DL, Fiedler J, et al. Pattern of SMARCB1 (INI1) and SMARCA4 (BRG1) in poorly differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterus: analysis of a series with emphasis on a novel SMARCA4-deficient dedifferentiated rhabdoid variant. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2015;19(4):198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2015.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agaimy A, Jain D, Uddin N, Rooper LM, Bishop JA. SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal carcinoma: a series of 10 cases expanding the genetic spectrum of SWI/SNF-driven sinonasal malignancies. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44(5):703–710. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agaimy A Proceedings of the North American Society of Head and Neck Pathology, Los Angeles, CA, March 20, 2022: SWI/SNF-deficient sinonasal neoplasms: an overview. Head Neck Pathol. 2022;16(1):168–178. doi: 10.1007/sl2105-022-01416-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rekhtman N, Montecalvo J, Chang JC, et al. SMARCA4-deficient thoracic sarcomatoid tumors represent primarily smoking-related undifferentiated carcinomas rather than primary thoracic sarcomas. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(2):231–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicholson AG, Tsao MS, Beasley MB, et al. The 2021 WHO classification of lung tumors: impact of advances since 2015. J Thorac Oncol. 2022;17(3):362–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Thoracic Tumours. 5th ed. IARC Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nambirajan A, Jain D. Recent updates in thoracic SMARCA4-deficient undifferentiated tumor. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2021;38(5): 83–89. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2021.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russell-Goldman E, MacConaill L, Hanna J. Primary cutaneous SMARCA4-deficient undifferentiated malignant neoplasm: first two cases with clinicopathologic and molecular comparison to eight visceral counterparts. Mod Pathol. 2022;35(12):1821–1828. doi: 10.1038/s41379-022-01152-l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoy SM. Tazemetostat: first approval. Drugs. 2020;80(5):513–521. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01288-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Italiano A, Soria JC, Toulmonde M, et al. Tazemetostat, an EZH2 inhibitor, in relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and advanced solid tumours: a first-in-human, open-label, phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(5):649–659. doi: 10.1016/sl470-2045(18)30145-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.First EZH2 inhibitor approved-for rare sarcoma. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:333–334. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-NB2020-006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson BG, Wang X, Shen X, et al. Epigenetic antagonism between polycomb and SWI/SNF complexes during oncogenic transformation. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(4):316–328. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kadoch C, Copeland RA, Keilhack H. PRC2 and SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complexes in health and disease. Biochemistry. 2016; 55(11):1600–1614. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b01191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alimova I, Birks DK, Harris PS, et al. Inhibition of EZH2 suppresses self-renewal and induces radiation sensitivity in atypical rhabdoid teratoid tumor cells. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(2):149–160. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knutson SK, Warholic NM, Wigle TJ, et al. Durable tumor regression in genetically altered malignant rhabdoid tumors by inhibition of methyltransferase EZH2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(19): 7922–7927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.l303800110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurmasheva RT, Sammons M, Favours E, et al. Initial testing (stage 1) of tazemetostat (EPZ-6438), a novel EZH2 inhibitor, by the Pediatric Preclinical Testing Program. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(3): e26218. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gounder MM, Stacchiotti S, Schöffski P, et al. Phase 2 multicenter study of the EZH2 inhibitor tazemetostat in adults with INI1 negative epithelioid sarcoma (NCT02601950). J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15) (suppl):11058. doi: 10.1200/jco.2017.35.15_suppl.11058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agaimy A SWI/SNF-deficient malignancies: optimal candidates for immune-oncological therapy? Adv Anat Pathol. 2022. Published online September 5, 2022. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nambirajan A, Dutta R, Malik PS, Bubendorf L, Jain D. Cytology of SMARCA4-deficient thoracic neoplasms: comparative analysis of SMARCA4-deficient non–small cell lung carcinomas and SMARCA4-deficient thoracic sarcomas. Acta Cytol. 2021;65(1):67–74. doi: 10.1159/000510323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gopakumar A, Kakkar A, Kaur K, et al. Fine needle aspiration cytology of metastatic SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal teratocarcinosarcoma: first report in literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2023;51(4):E129–E136. doi: 10.1002/dc.25102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]