Abstract

Introduction

Audio-visual recordings made by patients of their clinical encounters are increasingly common. This may be done with or without their doctors’ knowledge or consent and is considered admissible legal evidence. Many surgeons may feel uncomfortable with being recorded and lack knowledge regarding the legal implications. The aim of this study was to gauge how surgeons react to being recorded, and what specific medico-legal insight they have regarding these matters.

Methods

In total, 150 surveys were distributed to surgeons in two hospitals in South Wales by email, Survey Monkey and paper copy between 28 October 2019 and 9 March 2020. The survey was anonymous and recorded level of training, as well as four simple questions regarding how surgeons may react to being recorded and what they felt their legal rights were.

Results

There were 91 respondents: 28 consultants, 36 registrars and 27 junior surgical trainees. Of the respondents, 56% were uncomfortable with being recorded and 23% would stop a consultation if their patient insisted on recording it. These issues were most marked for junior surgical trainees. Sixty-two per cent of respondents were unaware of their legal rights and 21% believed they were legally able to refuse to continue a consultation. This belief was particularly marked among consultants.

Conclusion

Many surgeons are uncomfortable with being recorded and lack knowledge regarding their medico-legal standing. Education and guidance from the Royal Colleges would help address this issue and avoid misunderstanding when surgeons are faced with these potentially difficult scenarios.

Keywords: Surgical consultation, Audio-visual recording

Introduction

Audio-visual recordings made by patients are becoming increasingly common and many healthcare staff may be unaware of the implications. Mobile phones in particular are ubiquitous and may be used to record medical professionals with or without their consent or knowledge. A recent survey revealed that 15% of patients had secretly recorded a clinical encounter and a further 11% were aware of someone who had done so.1

Patients have utilised audio-visual recordings in court; not only when taken with the consent of their doctor, but also when taken covertly – even where consent was clearly refused.2 Legally, a healthcare professional does not have the right to refuse to be recorded during a consultation. A patient may record any part of their medical care and do with it as they wish, regardless of whether they have done so with the consent or knowledge of that medical professional.3,4

Many healthcare professionals feel uncomfortable being recorded, particularly if done so covertly. However, no official guidance currently exists from the General Medical Council (GMC) or surgical Royal Colleges regarding best practice in such circumstances. Specific guidance may of course be sought directly from medicolegal organisations.3,4 The recent COVID-19 pandemic has arguably made this issue more pressing, given the widespread use of exclusively audio-visual consultations by telephone or video call. These may be easily recorded and have been widely advised by leading bodies and publications.5–7

The aim of this study was to gauge how surgeons may react to being recorded, and what knowledge they have regarding the medico-legal implications. A secondary aim was to examine whether such opinions vary with experience and level of training.

Methods

A snapshot of opinion was taken by submitting a short survey to doctors in surgical departments across two hospitals in South Wales: The Royal Gwent Hospital, Newport, and University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff. In total, 150 surveys were distributed by email, Survey Monkey and paper copy between 28 October 2019 and 9 March 2020. The survey was anonymous and recorded level of training as well as four simple questions:

-

1.

How would you feel if a patient asked to make a recording of your consultation?

-

2.

Would you agree to continue the consultation if a patient insisted on recording it?

-

3.

Can you legally refuse to continue with the consultation in these circumstances?

-

4.

Are you aware of any official guidance regarding the making of audio-visual recordings by patients?

Question 1 was accompanied by a numerical rating scale (1–5) from ‘very comfortable’ to ‘very uncomfortable’. The remaining questions were accompanied by the options ‘Yes’, ‘No’ and ‘I don't know’ as appropriate. The results were collated and analysed for our primary and secondary aims.

Results

Of 150 surgeons invited, there were 91 (61%) responses in total across general surgery, ear, nose and throat, vascular and orthopaedic subspecialities. There were 28 consultants, 36 registrars and 27 junior surgical trainees. ‘Junior surgical trainees’ comprised surgical core trainees, junior clinical fellows and foundation year 2 surgical doctors. There were no significant differences between the surgical subspecialties. A breakdown of responses can be seen in Figures 1–4.

Figure 1 .

Responses to Question 1

Figure 4 .

Responses to Question 4

Twenty-four respondents (26%) stated they would feel ‘very’ or ‘quite’ comfortable if a patient asked to make a recording of their consultation, versus 51 (56%) who stated they would feel ‘very’ or ‘quite’ uncomfortable. Responses varied markedly between consultants and trainees, with 46% of consultants stating they would feel comfortable, versus 20% of registrars and 15% of junior surgical trainees. Correspondingly, 17% of consultants stated they would feel uncomfortable, versus 69% of registrars and 78% of junior surgical trainees (Figure 1).

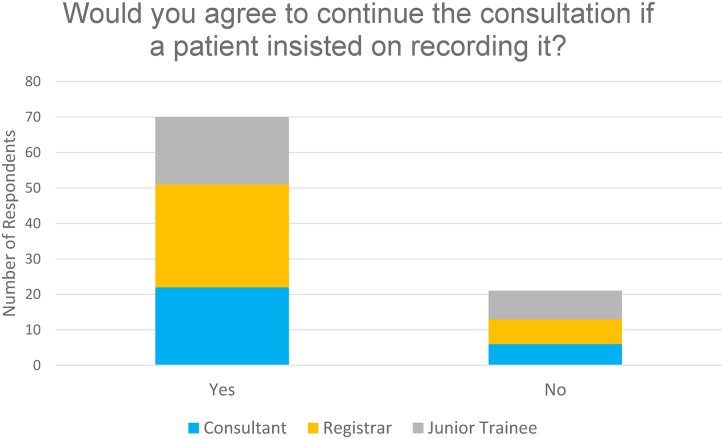

Seventy respondents (77%) stated they would continue with the consultation if a patient insisted on recording it, versus 21 (23%) who stated they would stop the consultation. Responses were broadly similar across levels of training, although junior surgical trainees were least willing to proceed (Figure 2).

Figure 2 .

Responses to Question 2

With regard to medico-legal issues, 16 respondents (18%) stated they could legally refuse to continue with the consultation if a patient insisted on making an audio-visual recording, versus 19 (21%) who felt they could not legally refuse. Fifty-six (62%) stated that they did not know whether they could legally refuse to continue. In the consultant group, 29% felt they could legally refuse, versus 17% of registrars and 7% of junior surgical trainees (Figure 3).

Figure 3 .

Responses to Question 3

Eighty respondents (88%) stated that they were not aware of any official guidance regarding the making of audio-visual recordings by patients, versus 11 (12%) who stated that they were aware of such guidance. Responses were very similar across levels of training (Figure 4).

Discussion

This simple study shows that most surgeons who participated were uncomfortable with being recorded (56% overall). Most respondents would continue with a consultation if a patient insisted on recording it, however a significant number would not continue (23% overall). These issues were most marked for junior surgical trainees and improved with experience and level of seniority. Worryingly, most felt unaware of their legal rights in such situations (62% overall) and many believed they were legally able to refuse to continue the consultation (21% overall). This belief was particularly marked among consultants and decreased in the registrar and junior surgical trainee groups. Furthermore, a large majority of respondents were understandably unaware of any official guidance, regardless of level of seniority (88% overall). The study was performed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Audio-visual recordings have become an ever-increasing presence in personal and professional life over recent years, with the rising use of mobile phones and other technology comprising audio-visual recording capabilities. There are now well over 79 million mobile phones in the UK, of which approximately 77% are considered ‘smartphones’.8 Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially 15% of patients had used such devices to secretly record clinical encounters, with a further 11% aware of someone who had done so.1 Since the pandemic has changed our consulting practices, surgeons have become increasingly exposed to consultations by telephone or video call in order to reduce patient contact, and this issue is likely to become ever more prevalent.5–7 Therefore, we must be mindful that consultations are often recorded, consider our reaction to this and educate healthcare professionals regarding their legal standing and responsibilities. Being proactive on this issue is particularly important to help avoid conflict, confrontations and misplaced objections that may serve to make bad situations worse.

The surgical Royal Colleges have not produced specific guidance on this burgeoning topic, however medical defence organisations have made the legal standpoint very clear.3,4,9 Put simply, a healthcare professional does not have the right to refuse to be recorded during a clinical encounter, no matter how uncomfortable they may feel about this. The Medical Protection Society and Medical Defence Union guidance states: ‘A patient does not require your permission to record a consultation. The content of the recording is confidential to the patient, not the doctor, so the patient can do what they wish with it. This could include disclosing it to third parties, or even posting the recording on the internet. If you would prefer not to be recorded, but the patient is insistent, you still owe a duty to the patient to assess their condition and offer any necessary treatment. It would be inadvisable for you to refuse to proceed with a consultation because the patient wishes to record it, otherwise the patient might come to harm if they were suffering from a serious or urgent condition.’3 ‘If you suspect a patient is covertly recording you, you may be upset by the intrusion, but your duty of care means you would not be justified in refusing to continue to treat the patient.’4

As shown in this study, many surgeons will be unaware of the rules regarding the use of audio-visual recordings as legal evidence. Indeed, recordings have been allowed in court which were not only taken with the consent of the doctor involved, but also those taken covertly without consent, and even where consent was explicitly refused.2 For example, in Mustard v Flower & Ors (2019) audio-recordings of clinical consultations were made on the advice of a solicitor and allowed as evidence during a personal injury claim. The various recordings were made with permission, covertly, and also after consent was refused, whereby the patient stated she accidentally failed to turn off the recording device. All were allowed as evidence in High Court, despite the Master of the case describing the making of covert recordings as ‘reprehensible’.10

There have been many recent examples of covert recordings being made by patients.11–13 However, clinical encounters are not covered under the UK Data Protection Act 1998 because such information is viewed as personal medical data which a patient may share as they see fit. Section 36 of the Act states: ‘Personal data processed by an individual only for the purposes of that individual's personal, family or household affairs (including recreational purposes) are exempt from the data protection principles and the provisions of Parts II and III’.14

Many would argue that audio-visual recordings should be viewed as positive and useful aids during patient consultations.3,4,15,16 It is well known that patients often remember little of the information relayed during clinical encounters. For example, approximately 40–80% of medical information provided by healthcare professionals is forgotten immediately.17,18 The greater the amount of information presented, the lower the proportion correctly recalled.19 Furthermore, almost half of the information that is recalled is incorrect.20 Therefore, recordings may be used to the advantage of both doctor and patient, especially in cases where understanding may be impaired by poor memory, learning difficulties, hearing difficulties or poor fluency in English.4,21 A healthcare professional is able to request a copy of recordings made by patients for inclusion in their medical record.3 They may also make their own recordings of clinical encounters with their patients’ permission and the GMC has produced thorough guidelines regarding production and storage.22

Evidence suggests that a majority of patients who record clinical encounters do so in order to relisten and share their consultation with others, particularly their family, as well as being motivated by the idea of owning a personal record. In one survey, 69% of respondents expressed a desire to record clinical encounters – approximately 50% wishing to do so covertly and the other 50% with permission.1,23 Audio-visual recordings have been shown to increase patient recall of medical information and reduce regret surrounding difficult decision-making.23,24 In one study involving audio-visual recording of female patients undergoing gynaecological surgery, 92% said a video of their operation improved understanding of their pathology and 81% said they would like to have a copy of the recording.25 Whether undertaking an operation or clinical consultation in the knowledge that one is being recorded changes clinician behaviour or clinical outcomes has yet to be investigated. Of course, healthcare professionals should always be working to the best of their abilities and the MPS has argued that: ‘Smartphone use in the consultation room should not affect the way you deliver your care. Doctors should always behave in a responsible and professional manner in consultations and consequently, any recording will provide concrete evidence of that.’3

Much of modern life is now being recorded and the technology is here to stay. It seems sensible to educate healthcare professionals about our legal rights and responsibilities in these situations, which we will likely face on an increasingly common basis in the coming years. The COVID-19 pandemic has made it significantly easier for patients to record clinical consultations – which are increasingly carried out by phone and video call – and it remains to be seen how outpatient clinics and other clinical encounters may be undertaken in its aftermath. More work should be done to examine the prevalence of audio-visual recordings being made by patients and encourage a more trusting relationship which may reduce the rate of this being done covertly. This current study of 91 surgeons reveals that guidance and education are urgently needed to improve our knowledge and response to recorded consultations.

Conclusions

Audio-visual recordings made by patients of clinical encounters are becoming increasingly common. This may be done covertly or with their doctors’ knowledge and is considered admissible legal evidence. This study has shown that a majority of doctors in surgical specialties currently feel uncomfortable with being recorded and many would refuse to continue with a consultation if a patient insisted on it being recorded. Furthermore, the majority are unaware of their legal rights in such situations and many believe they are legally able to refuse to continue a consultation. Legally, a doctor may not refuse to continue with a clinical encounter on the basis that that they do not wish it to be recorded; a patient may share their recording in whatever way they see fit.

Many argue that audio-visual recordings are beneficial and should be used more widely to help increase patient recall of medical information and aid difficult decision-making. A copy may be held by both healthcare professional and patient and stored in the patient’s medical record with their permission. Doctors should be educated regarding their legal rights and responsibilities during these encounters, which may become increasingly common in the context of COVID-19 and the use of consultations by telephone or video call. Being proactive on this issue may help avoid conflict, confrontations and misplaced objections when healthcare professionals are faced with this scenario. Urgent guidance and education by our Royal Colleges would help begin to address this.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Welsh Barber Surgeons for their help in disseminating many of the surveys used in this study.

References

- 1.Elwyn G, Barr PJ, Grande SW. Patients recording clinical encounters: a path to empowerment? Assessment by mixed methods. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e008566. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hyde J. Secret medical recordings ‘reprehensible’ but allowed as evidence. The Law Society Gazette, 2019. https://www.lawgazette.co.uk/law/secret-medical-recordings-reprehensible-but-allowed-as-evidence/5101817.article

- 3.Clements N. Digital dilemmas – patients recording consultations. Practice Matters, 2015. https://www.medicalprotection.org/uk/articles/digital-dilemmas-patients-recording-consultations

- 4.Zack P. Patients recording consultations. 2014. https://www.themdu.com/guidance-and-advice/journals/good-practice-june-2014/patients-recording-consultations

- 5.Royal College of Surgeons. COVID-19: Good Practice for Surgeons and Surgical Teams. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/standards-and-research/standards-and-guidance/good-practice-guides/coronavirus/covid-19-good-practice-for-surgeons-and-surgical-teams/

- 6.Razai MS, Doerholt K, Ladhani S, Oakeshott P. Coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19): a guide for UK GPs. BMJ 2020; 368: m800. 10.1136/bmj.m800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Shaw S, Morrison C. Video consultations for covid-19. BMJ 2020; 368: m998. 10.1136/bmj.m998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Dea S. Number of mobile phones per household in the United Kingdom (UK) in 2020. Statistica; 2020. Data obtained from the UK Office of National Statistics. https://www.statista.com/statistics/387184/number-of-mobile-phones-per-household-in-the-uk [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yentis SM, Shinde S, Bogod Det al. Association of Anaesthetists guideline: audio/visual recording of doctors in hospitals. https://anaesthetists.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=6PJRF6sEq-Y%3D&portalid=0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Mustard v Flower & Ors . England and Wales High Court (Queen's Bench Division) Decisions. [2019] EWHC 2623 (QB). https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/QB/2019/2623.html

- 11.Rodriguez M, Morrow J, Seifi A. Ethical implications of patients and families secretly recording conversations with physicians. JAMA 2015; 313: 1615–1616. 10.1001/jama.2015.2424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramachadran D. When patients secretly record their doctor visits. May 5, 2014. http://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2014/05/patients-secretly-record-doctor-visits.html.

- 13.Elwyn G. ‘Patientgate’—digital recordings change everything. BMJ 2014; 348: g2078. 10.1136/bmj.g2078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.UK Data Protection Act 1998. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1998/29/contents

- 15.Adamson DJ. Using CD disc recordings of oncology consultations to help patients handle large amounts of information. BMJ 2014; 348: g2428. 10.1136/bmj.g2428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burgess J, Davies M. Developing the use of digital recording of consultations to improve patient care. BMJ 2014; 348: g2427. 10.1136/bmj.g2427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessels RP. Patients’ memory for medical information. J R Soc Med 2003; 96: 219–222. 10.1258/jrsm.96.5.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephens MR, Gaskell AL, Gent Cet al. Prospective randomised clinical trial of providing patients with audiotape recordings of their oesophagogastric cancer consultations. Patient Educ Couns 2008; 72: 218–222. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGuire LC. Remembering what the doctor said: organization and older adults’ memory for medical information. Exp Aging Res 1996; 22: 403–428. 10.1080/03610739608254020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson JL, Dodman S, Kopelman M, Fleming A. Patient information recall in a rheumatology clinic. Rheumatol Rehabil 1979; 18: 245–255. 10.1093/rheumatology/18.1.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dommershuijsen LJ, Dedding CWM, Van Bruchem-Visser RL. Consultation recording: what Is the added value for patients aged 50 years and over? A Systematic Review. Health Commun 2021; 36: 168–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.General Medical Council. Making and using visual and audio recordings of patients. Ethical Guidance for Doctors. https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/making-and-using-visual-and-audio-recordings-of-patients.

- 23.Tsulukidze M, Durand MA, Barr PJet al. Providing recording of clinical consultation to patients—a highly valued but underutilized intervention: a scoping review. Patient Educ Couns 2014; 95: 297–304. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Good DW, Delaney H, Laird Aet al. Consultation audio-recording reduces long-term decision regret after prostate cancer treatment: A non-randomised comparative cohort study. Surgeon 2016; 14: 308–314. 10.1016/j.surge.2014.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papadopoulos N, Polyzos D, Gambadauro Pet al. Do patients want to see recordings of their surgery? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008; 138: 89–92. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]