Abstract

In the United States, adherence to follow up medical appointments among patients discharged from the emergency department varies between 26% and 56%, depending on the population. It is well known that patients face significant barriers to care within an increasingly complicated system of care. In an effort to better support patients, in 2020, NewYork-Presbyterian Queens implemented a Patient Navigator Program with 7 bilingual Patient Navigators who were trained to deliver culturally sensitive education and support, and to schedule follow up appointments for patients experiencing barriers to care. Between February 2020 and December 2022, 30,164 patients were supported by the 7 Patient Navigators. Ninety-four percent of patients without a primary care provider had a new provider and appointment upon discharge, and 81% of patients attended the appointment scheduled by the Patient Navigator. This study demonstrates that Patient Navigators can work alongside clinical colleagues, and as members of emergency department health care teams, to support patients to connect to care and to attend follow up appointments. It also highlights that Patient Navigators are uniquely qualified to build trust and to support patients to achieve appropriate, continuous care within a rapidly evolving health care system.

Keywords: Access to Care, Patient navigators, Social determinants of health, Peer-Based Support, Culturally Sensitive Care, Emergency department, Prevention, Medical home, Continuity of care, Community health workers

1. Introduction

In the United States, adherence to follow up medical appointments among patients discharged from the emergency department (ED) varies between 26% and 56%, depending on the population (Kyriacou et al., 2005). While the United States healthcare system can be challenging to navigate under the best of circumstances, it is particularly so for patients without access to primary care providers, without insurance, and among those who represent socioeconomically disadvantaged communities.

These system navigation challenges are compounded in times of crisis, such as during a pandemic. Community Health Workers (CHW)s have long been shown to improve health outcomes for vulnerable patients while nimbly adapting to challenges within the healthcare system and within the communities they support (Peretz et al., 2020). In the ED, CHWs trained as Patient Navigators, who speak the languages spoken by patients, and who are members of health care teams, are uniquely positioned to build trust and to empower patients and their caregivers to achieve appropriate, continuous care. The time has come to embrace Patient Navigators as essential health care team members who can deliver the patient-centered services and support most needed by patients in order to successfully navigate our health care system, and to reduce preventable utilization (Enard and Ganelin, 2013).

In 2008, public health and clinical leaders from NewYork-Presbyterian created a Patient Navigator Program to support patients who frequent the ED because they are not well connected to care. The objective was to deliver culturally sensitive, peer-based support to equip patients with the information and tools needed to confidently navigate the healthcare system, to safely connect to post-discharge care, and to establish a medical home. In February 2020, after expanding to 2 additional NewYork-Presbyterian Hospitals, this proven model expanded to NewYork-Presbyterian Queens, located in a borough in which nearly 50% of the more than 2.2 million residents are foreign born.

2. Methods

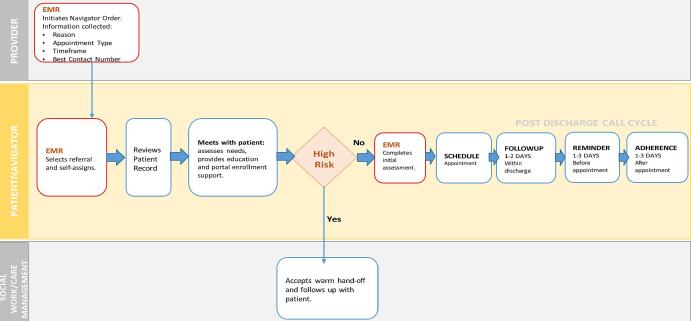

Seven full-time, bilingual Patient Navigators who represent the communities served and who speak the languages most frequently spoken within the local community, including Spanish, Mandarin, and Cantonese, were hired. The recruitment process was supported by the Hospital Human Resources team and candidates were screened for prior health-related experience, strong communication skills, and knowledge of resources to support patient needs. They were trained to deliver culturally sensitive education and support, to connect patients to health insurance and financial resources, and to schedule primary and specialty healthcare appointments. Providers referred patients to the Patient Navigator Program by initiating a referral order in the electronic medical record. Referral criteria included patients who did not have a primary care provider or needed a new one and patients who were underinsured or uninsured. Upon receiving the referral, Patient Navigators reviewed the patient record before visiting the patient at the bedside to offer education and the opportunity to enroll into the Patient Navigator Program. If the patient consented to receive support from the Patient Navigator Program, including consent to share the minimal patient information necessary to schedule follow up appointments, the Patient Navigators documented that the patient provided verbal consent in the electronic medical record. Patient Navigators were required to enroll 5 new patients per day, and often exceeded this target, and spent approximately 1 hour with each patient, although the amount of time spent per patient was based on the individual patient needs. By applying a patient-centered approach, each patient’s needs, preferences, and insurance status informed appointment scheduling and, after the patient was discharged, the Patient Navigators extended the relationship between the ED and the patient through telephonic support until the patient successfully presented to the follow up appointment (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

ED Patient Navigator Workflow.

When COVID-19 struck New York City, the greatest concentration of early cases was identified within Latino and Black communities in Queens (Correal and Jacobs, 2020). For physicians working in the ED, there was no roadmap to follow and little time to plan for the rapidly increasing patient volume, and heightened acuity and complexity. At NewYork-Presbyterian Queens, ED leaders quickly mobilized to develop an interdisciplinary response that included leveraging the strengths of the new Patient Navigators to support patients with COVID-19. Due to limited bed availability, many of the patients with moderate COVID-19 symptoms were discharged with pulse oximeters, oxygen concentrators, and a time-sensitive follow up plan that included a mandatory respiratory follow up within 24 h via telehealth or phone. Despite being moved outside of the ED due to safety and space constraints, the Patient Navigators remained in real-time contact with their clinical colleagues through daily huddles, shared chat functionality, and the electronic health record, quickly responding to urgent referrals and following through within the required timeframe. In addition to safely connecting scared, vulnerable patients to care within a very short timeframe, the Patient Navigators helped patients adapt to a newly digital health care system, supporting them to participate in telehealth visits when possible and, when not, to participate by phone. The study was reviewed by the local Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt.

3. Results

The ability to quickly adapt to evolving patient needs, and to changes within internal and external environments, is a hallmark of this model and one that has enabled the team to steadily guide patients to care under unprecedented circumstances, while working as part of a larger healthcare team to collectively address new challenges as they arose. Between program inception in February 2020 and December 2022, 30,164 patients were supported by 7 Patient Navigators and, among patients without primary care providers, 94% had primary care providers and appointments upon discharge. For those patients with appointments scheduled by the Patient Navigator, 81% attended the follow up appointment. Within the subset of patients with moderate COVID-19 symptoms, between March 2020 and May 2022, the Patient Navigators supported 418 patients, of whom 90% attended both a respiratory and primary care appointments within the designated timeframe.

To address the widening digital divide, the Patient Navigators were quickly trained to help patients enroll onto the patient portal that would enable them to participate in virtual visits, to access their health information, to schedule appointments, and to request medication refills. When portal enrollment and telehealth appointments were not options due to low digital literacy or other barriers, they supported patients to participate in telephonic appointments and to connect directly with providers as needed.

4. Discussion

Integrating new team members into an established health care team within a large and busy ED comes with a unique set of challenges, including developing and aligning workflows, establishing appointment scheduling processes across multiple internal and external clinical practices, and gaining buy-in from ED stakeholders and colleagues. Aiding in this implementation process was the strong support from clinical and administrative leaders, who championed the benefits of patient navigation and who supported each phase of implementation, helping to address each barrier as it was presented. It also helped to establish interdisciplinary stakeholder meeting from inception through implementation, allowing the Patient Navigator Program leaders and Patient Navigators to develop and strengthen key relationships with colleagues throughout the Hospital and community.

It is well known that healthcare inequities in the United States directly contribute to poor health outcomes, particularly among the underinsured and uninsured who frequently forgo preventive care. Medicaid has greatly improved access to care for millions of Americans but with inconsistent coverage, many patients with Medicaid still receive suboptimal care (Natale-Pereira et al., 2011).

Compounding these challenges is an inherently complicated health care system that is difficult to navigate for anyone, much less those with additional barriers to care. The benefits of patient navigation were brought to light in the early 1990s with the recognition that there is often a critical window of opportunity to increase the chance of survival among patients with cancer. As the role of Patient Navigator extended to support a broader patient population, outcomes pointed to improved appointment adherence, leading to better care and reduced preventable utilization among patients supported by Patient Navigators (Freeman and Rodriguez, 2011).

5. Conclusion

The Patient Navigators ability to quickly build trust, to communicate in a patient’s preferred language, and to understand each patient’s unique needs enables them to meet patients where they are and to help them successfully navigate complicated appointment scheduling processes, financial systems and, more recently, patient portals and telehealth appointments. While COVID-19 further exposed the significant health disparities and challenges associated with our country’s healthcare system, it also highlighted the ways in which Patient Navigators are uniquely qualified to provide the culturally sensitive, patient-centered support that patients need now more than ever to address immediate needs and to establish continuous care. With mounting evidence in favor of the critical role that Patient Navigators play, it is time to redefine our definition of healthcare teams to includes them as essential healthcare team members whose services a growing number of patients cannot go without.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Patricia Peretz: Conception or design of the work, Data analysis and interpretation, Drafting the article, Critical revision of the article, Final approval of the version to be published. Henley Vargas: Conception or design of the work, Data collection, Data analysis and interpretation, Critical revision of the article. Maria D’urso: Conception or design of the work, Critical revision of the article. Stephanie Correa: Data collection, Critical revision of the article, Final approval of the version to be published. Andres Nieto: Conception or design of the work, Critical revision of the article, Final approval of the version to be published. Erina Greca: Conception or design of the work, Data collection, Data analysis and interpretation, Critical revision of the article. Jaclyn Mucaria: Critical revision of the article, Final approval of the version to be published. Manish Sharma: Conception or design of the work, Drafting the article, Critical revision of the article, Final approval of the version to be published.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

No conflicts of interest to report. This work was supported by Pilar Crespi Robert and Stephen Robert.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Correal, A, Jacobs, A. A Tragedy Is Unfolding’: Inside New York’s Virus Epicenter. New York Times. April 10, 2020, Section A, Page 1.

- Enard K.R., Ganelin D.M. Reducing preventable emergency department utilization and costs by using community health workers as patient navigators. J. Healthc. Manag. 2013;58(6):412–427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman H.P., Rodriguez R.L. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer. 2011;117(15 Suppl):3539–3542. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou D.N., Handel D., Stein A.C., Nelson R.R. BRIEF REPORT: factors affecting outpatient follow-up compliance of emergency department patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2005;20(10):938–942. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0216_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natale-Pereira A., Enard K.R., Nevarez L., Jones L.A. The role of patient navigators in eliminating health disparities. Cancer. 2011;117(15 Suppl):3543–3552. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretz P.J., Islam N., Matiz L.A. Community Health Workers and COVID-19 – addressing social determinants of health in times of crisis and beyond. N. Engl. Med. 2020;383(19):e108. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2022641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.