Abstract

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) was utilized to functionalize the surface of zinc ferrite nanoparticles (NPs) synthesized by the hydrothermal process in order to prevent aggregation and improve the biocompatibility of the NPs for the proposed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) agent. Various spectroscopy techniques were used to examine the NPs’ structure, size, morphology, and magnetic properties. The NPs had a cubic spinel structure with an average size of 8 nm. The formations of the spinel ferrite and the PEG coating band at the ranges of 300–600 and 800–2000 cm–1, respectively, were validated by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. The NPs were spherical in shape, and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy with mapping confirmed the presence of zinc, iron, and oxygen in the samples. The results of high-resolution transmission electron microscopy revealed an average size of 14 nm and increased stability after PEG coating. The decrease in zeta potential from −24.5 to −36.5 mV confirmed the PEG coating on the surface of the NPs. A high saturation magnetization of ∼50 emu/g, measured by vibration sample magnetometer, indicated the magnetic potential of NPs for biomedical applications. An MTT assay was used to examine the cytotoxicity and viability of human normal skin cells (HSF 1184) exposed to zinc ferrite and PEG@Zn ferrite NPs at various concentrations. After 24 h of treatment, negligible cytotoxicity of PEG-coated NPs was observed at high concentrations. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suggested that PEG@Zn ferrite NPs are a unique and perfectly suited contrast agent for T2-weighted MRI and can successfully enhance the image contrast.

Keywords: magnetic nanoparticles, contrast agent, magnetic resonance imaging, relaxivity, ferrites

Introduction

Recent progress in nanobiomaterial research has resulted in the discovery of magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) with considerable promise for biomedical applications.1−3 It has proven possible to use magnetic nanoparticles in drug delivery,4 cell targeting via protein and small molecule binding, diagnostic applications,5 intracellular drug release,6,7 imaging,8,9 and combination treatments.10,11 Therefore, due to the unique physical features of MNPs that enable them to activate at the cellular and molecular levels of biological interactions, they have the potential to alter conventional clinical diagnosis and therapy12,13 and are commonly employed for medical diagnostics.14 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a painless and safe diagnostic procedure that employs a magnetic field and radio frequency to generate high-resolution images of the organs and structures of the body.15,16 MNPs also require a surface coating that is nontoxic and biocompatible and enables targeted distribution.17 As MRI contrast agents, paramagnetic or superparamagnetic metal ions are utilized that boost contrast sensitivity because these materials can cause changes in relaxation times (brighter/T1 and darker/T2).18 Metal ions that are paramagnetic or superparamagnetic can produce effective MRI contrast in the form of nearby spin water molecules (T2 or transverse relaxation rather than T1 or longitudinal relaxation).19 A number of MNP formulations are currently being developed for use in MRI; however, there exists a need to establish a mixed formulation for these specific demands. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles have been widely investigated as MRI contrast agents, and various formulations have achieved clinical approval. Nevertheless, due to existing detection limits and a lack of specific identification, their widespread utility has yet to be realized.

Due to their low toxicity and high magnetic properties, iron oxide-based MNPs are particularly suitable for a number of applications. The formation of magnetic shells with different coating materials around particles20,21 and the modification of particle composition by introducing additional elements into their crystalline structure22−24 are the most common methods for producing NPs suitable for biomedical applications. Using one-pot decomposition, superparamagnetic manganese, cobalt, and zinc–iron-doped iron oxide NPs were produced. The prepared MNPs were investigated for their potential use as contrast agents in MRI and hyperthermia therapy agents. Cobalt substitution increased coercive fields at low temperatures, but zinc substitution significantly increased saturation magnetizations, and manganese had a smaller effect on overall magnetic properties. The transverse relaxation coefficients (r2) of the MNPs were significantly higher than 100 mM–1 s–1, indicating a substantial improvement over several commercially available T2-contrast agents based on pure iron oxide NPs.25 Elsewhere, the crystal structures, magnetic characteristics, and contrast abilities of manganese-doped magnetite NPs were reported, where, as the manganese doping level increased, the lattice distances and saturation magnetizations rose gradually. Manganese-doped magnetite NPs exhibited a saturation magnetization (Ms) of 89.5 emu/g with an exceedingly strong T2 contrast effect with an r2 value of 904.4 mM–1 s–1 at 7.0 T. Compared to iron-oxide-based commercially available products, prepared NPs in the ratio of Mn/Fe (1:7) showed high T2 contrast ability and gave much greater signal sensitivity for imaging live subjects.26 An r2 relaxivity of 270 mM–1 s–1 and sensitive in vivo liver MRI in mice were achieved by encapsulating manganese-doped superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoclusters with the amphiphilic diblock copolymer methoxypoly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(caprolactone) (mPEG-b-PCL).27 To limit quick absorption by the reticuloendothelial system and permit prolonged blood circulation, manganese ferrite nanoparticles were coated with a thick PEG shell, which also increased the stability of NPs in aqueous environments. The combination of biocompatibility, high T2 effect, and excellent r2/r1 values at low magnetic fields confer these NPs desirable properties as MRI contrast agents.28 Although recent literature reported many types of spinel-structured ferrites as MRI contrast agents, zinc is the most suitable candidate as a dopant since the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends high reference daily values (DVs) for zinc and iron of 15 and 18 mg, which are significantly higher than the values for other potential dopants, such as manganese and cobalt at 2 mg.16 Chaudhary et al. optimized zinc-doped ferrite NPs (Zn0.4Fe2.6O4) with a diameter of 24 nm as MRI contrast agents and compared them to commercial ferrite NPs. A substantially higher enhancement in T2 (1.22-fold) and a slightly higher T1 (1.09-fold) contrast were reported compared to commercial ferrite nanoparticles. Zinc substitution not only enhanced MRI contrast properties but also significantly minimized the chances of iron overloading by iron cation substitution.16

Spinel ferrite NPs have superparamagnetic characteristics, although the majority of them display poor chemical stability, and as a consequence, their surfaces need to be modified. Furthermore, ferrite NPs have a high surface-to-volume ratio and are prone to aggregation. For effective MRI applications, ferrite NPs should be capped with biocompatible polymers to stabilize NP dispersions under physiological circumstances.29 As uncoated NPs face several obstacles, including cellular absorption, colloidal stability, and clearance by the reticuloendothelial system,30 conjugation with bioactive molecules is essential because it improves biocompatibility and blood circulation, enables optical detectability, and, most importantly, does not induce toxicity in the body.31 Therefore, covering the surface of nanomaterials with such polymers that are naturally abundant, hydrophilic, biocompatible, and biodegradable will boost the hydrophilicity and dispersibility of NPs, thereby enhancing their biocompatibility and biodegradability.31,32

PEG’s uncharged and hydrophilic properties, in addition to its low toxicity and immunogenicity, render PEG-coated NPs immune-invisible. These characteristics make PEG-coated NPs appealing for biological applications.33,34 PEG-diacid-functionalized MnFe2O4 NPs were synthesized using the solvothermal technique, and their cytotoxicity, MRI, and hyperthermia evaluations were performed, where a transverse relaxivity of 216 mM–1 s–1 was achieved. The PEG-diacid coating of the NPs offered colloidal stability appropriate for biological applications, and a cytotoxicity study on breast cancer and normal epithelial cell lines demonstrated that the prepared NPs were biocompatible but had a considerable toxic effect on breast cancer cells.35 Elsewhere, PEG coating was applied to functionalize La1–xSrxMnO3 superparamagnetic NPs, and excellent colloidal stability, hemocompatibility, and biocompatibility were demonstrated. PEG-coated NPs exhibited a 3-fold r2 value compared to bare NPs.36

PEG has been the most studied synthetic hydrophilic polymer among other polymers. By limiting opsonization and providing steric hindrance, PEG has established itself as a good NP stabilizer.37 As a result, functionalization with PEG would slow down NP clearance by the reticuloendothelial system and increase their permeability and retention effect in vivo, thereby increasing the half-life of MNPs in circulation.38,39 Numerous parameters, including processing procedures, functionalization, and calcination/sintering, play a crucial role in ensuring that MNPs work ideally for their intended uses. These variables can have a substantial impact on the size and shape of the produced particles, making it necessary to pick the most suitable preparation procedure from the numerous synthesis approaches.40 Different types of ferrites have been synthesized using a variety of procedures, such as the microwave approach,41 solution combustion,42 hydrothermal decomposition,43 solid-state reaction,44 sol–gel,45,46 and coprecipitation.47 For the preparation of MNPs, hydrothermal synthesis48,49 is preferred due to its better yield, simplicity, low cost, and high degree of compositional control in terms of particle size and crystallinity.

Although zinc ferrite NPs with different types of surface coatings, such as silica,50 graphene oxide,51 chitosan,52 and PEG,53 were reported previously, saturation magnetization, cytotoxicity, and T2 contrast effect modifications need further investigation. To the best of our knowledge, there is insufficient information on the MRI contrast enhancement impact and the biocompatibility evaluation of PEG-coated zinc ferrite NPs. In this study, we report zinc ferrite NPs stabilized with a PEG coating (MW = 6000 g/mol), referred to as PEG@Zn ferrite NPs, with low toxicity and small crystallite size achieved via the hydrothermal synthesis method. The substitution of zinc to ferrite nanoparticles and coating with PEG resulted in biocompatible behavior and considerably controlled saturation magnetization (Ms), hence improving MRI contrast while minimizing the risk of iron overloading through iron cation replacement and preventing the quick clearance of MNPs. This unique magnetic nanoparticle with improved magnetic characteristics and reduced adverse effects on the human body is a potential candidate for MRI applications.

Materials and Methods

PEG@Zn Ferrite NPs Synthesis

Hydrothermal synthesis was utilized to produce Zn ferrite NPs with a nominal composition of ZnFe2O4. The spinel structure of ZnFe2O4 is normal, with Zn2+ ions in the A-site and Fe3+ ions in the B-sites. The nanocrystalline ZnFe2O4 system always appears as a normal spinel with Zn2+ and Fe3+ ions distributed over the A- and B-sites; hence, the formula is (Zn1−δ2+Feδ)[Znδ2+Fe2−δ]O42–, where δ is defined as the fraction of A-sites occupied by Fe3+ cations and is dependent on the technique of synthesis. δ for Zn ferrite prepared by the hydrothermal technique is zero considering a normal spinel.54 The distribution of Fe3+ into tetrahedral and Zn2+ into octahedral interstices is the main property of nanocrystalline ZnFe2O4 by the hydrothermal method. This cationic redistribution causes the formation of two magnetic sublattices, (A) and (B), which are responsible for the increased magnetization observed as compared to normal ZnFe2O4. As a result, nanosized ZnFe2O4 with a normal spinel structure has significantly higher magnetization.55,56 Iron(II) nitrate hexahydrate, zinc nitrate hexahydrate, sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and PEG (MW = 6000 g/mol) of 99% purity were acquired from Merck. All the nitrates were initially dissolved in distilled water. Then, drop by drop, NaOH solution was added to the stirring solution until the desired pH of 12 was reached. The precipitate was then deposited in an oven in a hydrothermal autoclave reactor for 10 h at 200 °C.57 The precipitates were washed many times with distilled water and 100% ethyl alcohol to remove unreacted products, then dried at 80 °C for 8 h, and calcined overnight at 500 °C for better crystallinity and magnetization. The chemical reaction is as follows:

With an ultrasonic bath, 20 mg of ZnFe2O4 was mixed into 1 mL of deionized water to make the coated NPs. PEG–water was prepared by combining 75 mg of PEG with 1.5 mL of deionized water and stirring for 20 min. Slowly, the obtained solutions were added to the ZnFe2O4 MNPs. The finished solution was agitated at room temperature for more than 6 h, then collected, rinsed with deionized water, and dried in a vacuum oven at 50 °C overnight.

Analytical Methods

Using a powder X-ray diffractometer (XRD, D8 Advanced), the purity and spinel structure of the produced samples at 2θ range from 10° to 90° with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54065 Å) were measured. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR, Bruker Vector 22, Germany) spectroscopy was used to evaluate the integrity of the prepared NPs. After combining 1 mg of ferrite sample with 100 mg of potassium bromide (KBr), compressed pellets were used to collect the spectra in the range of 300–4000 cm–1. The hydrodynamic size (mean particle size) and zeta potential were validated using dynamic light scattering (DLS; Zeta sizer Nano ZS-90, Malvern, U.K.). A field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, JSM-6700F, JEOL, Japan) was used. FESEM snapshots were converted to 3D images using the ImageJ software. Utilizing an energy dispersive spectrum (EDS, Thermo Noran System 7), the exact metal ion composition of the MNPs was determined. A transmission electron microscope (TEM, Hitachi H7650, Japan) coupled with high-resolution TEM (HRTEM), operating at 100 kV, was used to image the NPs, which were prepared by dispersing in methanol before being drop-cast onto a carbon-coated copper grid and air-dried. A vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM, Lake Shore model 7307, U.S.A.) was used to obtain the magnetic properties of MNPs at room temperature.

Cytotoxicity Studies

Human normal skin cells (HSF 1184) were cultured in high glucose DMEM media supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, VWR, U.S.A.) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, U.S.A.). Cells were then maintained at 37 °C in a humid atmosphere containing 5% CO2 (v/v). All in vitro investigations were conducted during the exponential growth phase of the cells. The HSF 1184 cell line was cultured in flasks for 24 h, and its exponential growth phase was measured. Then, 200 μL of cell suspension containing 5 × 104 cells per well was added to each well of a sterile 96-well microplate and incubated overnight at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 98% humidity.58 The cells were then treated for 24 h with 50 μL of zinc ferrite and PEG-coated zinc ferrite nanoparticles (0–1000 μg/mL) Following this, 20 μL of MTT reagent in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide was added to each well and incubated for 4 h. As negative controls, untreated cells, medium with 100% cell viability, and a blank were utilized. To dissolve the violet crystals produced from live cells, 200 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide solution was added to each well after the MTT solution was withdrawn. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using an ELISA microtiter plate reader after 15 min. The experiments were carried out in triplicate, and the cell viability percentage was calculated using the following formula:59

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Using a Phantom

Using an agarose phantom study, the contrast ability of the samples was evaluated. To do this, various concentrations of PEG@Zn ferrite NPs were suspended in agarose gel (1%, w/v) and scanned using T2-weighted imaging protocols on a clinical 1.5T MR scanner (Avanto, Siemens, Germany). T2-weighted images were collected using the following parameters: 1.5T, fast spin–echo, repetition time TR = 2500 ms, echo time TE = 30–180 ms (increment of 6 ms), FOV = 16 cm2, resolution = 256 × 256 points, and slice thickness = 6 mm.

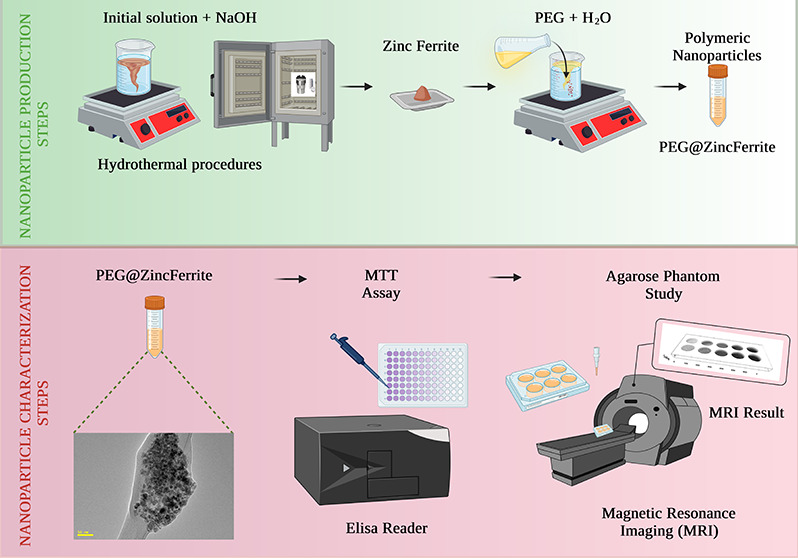

In a 96-well plate, various concentrations of Zn ferrite NPs and PEG@Zn ferrite NPs (in μg/mL) were suspended in 1% (w/v) agarose gel.60 The plate was put into a knee coil for MRI. By fitting a curve to plots of 1/T2 (in s–1) vs the total of the concentration (in μg/mL) of different concentrations of Zn ferrite NPs and PEG@Zn ferrite NPs, the values of r2 were determined. Figure 1 is a summary of the experimental and analytical study schematic diagram.

Figure 1.

Schematics of experimental and analytical study of Zn ferrite and PEG@Zn ferrite NPs.

Ferrite nanoparticles were generated in two stages: first, metal salts were transformed into hydroxides, and then hydroxides were transformed into nanoferrites. The solid solution of metal hydroxides eventually changed into Zn ferrite by heating at 80 °C, and the subsequent reaction required sufficient time and temperature for this transformation to occur completely; by calcination at a high temperature, one could obtain better crystallinity for the prepared NPs.61

Figure 2 shows the powder XRD pattern for Zn ferrite and PEG@Zn ferrite NPs obtained using the JADE program, with a Gaussian fit of the peaks (311) as an inset. The diffraction peaks associated with Bragg’s reflections of Zn ferrite NPs were observed and successfully indexed as (220), (311), (222), (400), (422), (440) and (511) planes, which correspond to pure phase with spinel structure and match with standard JCPDS card no. 73-1964.62 The widening of peaks represents the growth of nanocrystals. The spinel ferrites of PEG@Zn ferrite NPs had diffraction peaks that are comparable to those of Zn ferrite NPs. Similar diffraction patterns of PEG@Zn ferrite NPs suggest that the PEG coating had no influence on the crystalline structure of Zn ferrite NPs.62 The obtained data indicate the successful incorporation of the PEG coating on the surface of Zn ferrite NPs.63 The XRD pattern (Figure 2) illustrates that after coating with PEG, the crystallite size of Zn ferrite NPs increases. This could be because the interaction of Zn ferrite NPs with polymer (PEG) causes some of the small particles to join together and form large particles, which is also confirmed by the shift in lower angle peak position. A similar behavior has also been reported for nickel zinc ferrite nanoparticles coated with PVA.64 Ehi-Eromosele et al. investigated the colloidal stability of Co0.8Mg0.2Fe2O4 and demonstrated that, as crystallite size increased after PEG coating, some of the smaller particles may have joined together to form larger particles, which is consistent with the current study.65

Figure 2.

XRD pattern for (a) Zn ferrite NPs and (b) PEG@Zn ferrite NPs with the Gaussian fit of the peaks (311) (inset).

The structural parameters such as crystallite size, lattice constant (a), cell volume (V), X-ray density (dx) and hopping lengths (L) were calculated using the formulas from the literature.66 All calculations use the d spacing values and the corresponding (hkl) lattice parameters, and Table 1 summarizes the structural parameters for the NPs. As shown in Table 1, the lattice constant characteristics of PEG@Zn ferrite are lower than those of the uncoated samples. The reduction of the average lattice constant is due to the appearance of PEG, which causes the strain value to decrease; such behavior has also been reported by other researchers.67

Table 1. Structural Parameters Calculated Using X-ray Diffraction Data.

| Samples | DXRD | a | V | L | dx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn ferrite | 8 | 8.3691 | 586.1951 | 2.9589 | 4.23900 |

| PEG@Zn ferrite | 14 | 8.3221 | 576.3614 | 2.9423 | 4.43123 |

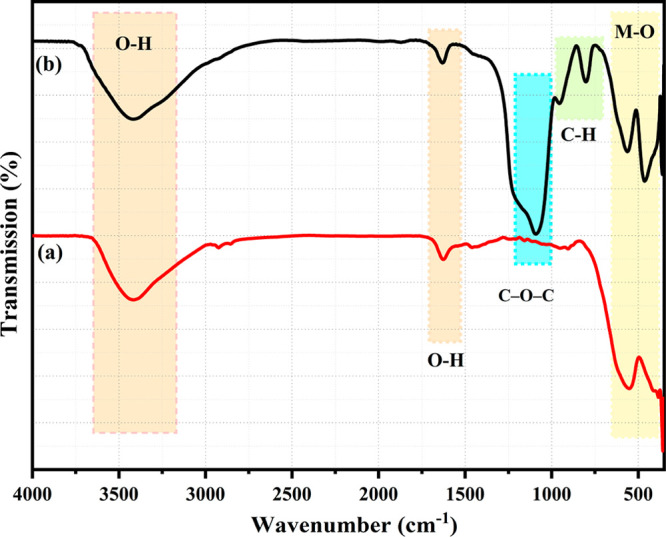

FTIR spectroscopy was utilized to identify the bonds responsible for the alteration of NPs by PEG molecules. The absorption spectra of Zn ferrite and PEG@Zn ferrite NPs are depicted in Figure 3. The tetrahedral and octahedral stretching vibrations of metal oxygen emerge as two absorption bands between 300 and 600 cm–1, respectively.66 The peak observed at 802 cm–1 is assigned to the deformation vibration of Fe–OH.68 The absorption band at 800–1000 cm–1 corresponds to the stretching of the C–H bonds of PEG. The absorption bands at 3400 and 1600 cm–1 correspond to the stretching and vibration of the O–H bond, respectively. In addition, the absorption bands at 1086 cm–1 are the result of the bending vibration of the C–O–C bond.63 These results corroborate the coating and adhesion of PEG to the surfaces of the Zn ferrite NPs, and Table 2 provides a description of the bands of Zn ferrite and PEG@Zn ferrite NPs.29,69,70

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of (a) PEG@Zn ferrite NPs and (b) Zn ferrite NPs.

Table 2. FTIR Spectra of Zn Ferrite and PEG@Zn Ferrite NPs.

| Samples | IR region or bands (cm–1) | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc ferrite NPs | 3418 | v(OH) stretching |

| 1623 | v(OH) bending | |

| 403 | v(M–O) stretching | |

| 550 | v(M–O) stretching | |

| PEG-coated zinc ferrite NPs | 3436 | v(OH) stretching |

| 1620 | v(OH) bending | |

| 1085 | v(C–O–C) stretching | |

| 938 | v(C–H) bending | |

| 875 | v() bending | |

| 800 | v(Fe–OH) stretching | |

| 558 | v(M–O) stretching | |

| 443 | v(M–O) stretching |

The observed FESEM results reveal that the produced Zn ferrite NPs had a spherical form (Figure 4a). The aggregation in the FESEM images is the result of magnetic NP interactions, which have been documented before for many other nanocrystalline spinel ferrites.71 As a result of calcination, heat treatment led to agglomeration, which is typical for spinel ferrites. Consequently, it appears unavoidable that agglomeration will occur at the elevated calcination temperature.71 Also, the grains appear to have agglomerated in some areas, which might be due to the release of gases during the burning process. The micrograph depicts the formation of powder with an average particle size of less than ∼8–10 nm. This value agrees well with that calculated from the XRD peak broadening. To estimate the average particle size, the diameters of about 160 particles were measured using ImageJ software, and the average particle size histogram is added as Figure 4b.72 The related EDS chart of the Zn NPs sample in Figure 4c indicates that Zn, Fe, and O elements can be validated with respective mass percentages of 30.3%, 47.3%, and 22.4% and calculated atomic percentages of 17.03%, 31.11%, and 51.85%, respectively, which are in agreement with the molecular formulation.73 It also shows that the calculated mass percentages in Table 3 are comparable with the observed values. As a result, the hydrothermal synthesis process is an effective method for producing zinc ferrite NPs with high homogeneity. The EDS elemental mapping micrographs of Zn ferrite NPs are depicted in Figure 4d. Clearly, the existence of elements Zn, Fe, and O is verified and can be distinguished in the EDS mapping with three distinct colors, indicating that the elemental distributions in the final products are homogeneous and highly pure.

Figure 4.

(a) FESEM micrograph, (b) size histogram, (c) EDS profile, (d) EDS mapping of Zn ferrite NPs prepared by hydrothermal method.

Table 3. Elemental Composition of ZnFe2O4 NPs.

| Element | Symbol | Atomic weight | Atoms | Mass % calculated | Mass % observed | Atomic % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc | Zn | 65.38 | 1 | 27.12% | 30.3% | 17.03% |

| Iron | Fe | 55.845 | 2 | 46.33% | 47.3% | 31.11% |

| Oxygen | O | 15.9994 | 4 | 26.54% | 22.4% | 51.85% |

TEM investigation revealed that the initial Zn ferrite NPs generated by the hydrothermal technique were less than 10 nm in size (Figure 5a). The particle size distribution was quite homogeneous, and the shape of the produced NPs was mostly spherical. TEM validated the results obtained from FESEM and the crystal size predicted by the Scherrer equation from XRD studies. XRD investigation determined the crystal size to be around 8 nm. Also, it was discovered that uncoated NPs exhibit aggregation. Figure 5b depicts HRTEM images of PEG@ Zn ferrite NPs having a quasi-spherical morphology. The 3D structural images for uncoated NPs confirmed the homogeneous preparation (Figure 5c). After PEG functionalization, the dispersibility of the NPs increased, which could be due to the formation of a nonmagnetic polymer surface layer. These PEG-functionalized NPs had an average diameter of 15 nm, as calculated by the size histogram (Figure 5d), and these biologically active particles display long-term high stability. Lattice fringes with a width of 0.2 nm correspond to the d spacing of (311) plane. These differential lattice fringes indicate the crystalline character of the sample formulations. Several small nanoparticles attached together as aggregates by mutual magnetic attractions to form the core and the presence of the PEG layer can be confirmed (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

(a) TEM images of uncoated Zn ferrite NPs, (b) HRTEM image of PEG-coated Zn ferrite NPs, (c) 3D structural image of uncoated Zn ferrite NPs and (d) size histogram of PEG-coated Zn ferrite NPs.

To find out the hydrodynamic sizes and distributions, 0.1 g of suspended Zn ferrite and PEG@Zn ferrite NPs were used. The XRD and morphological results were in good agreement (Table 4). The average hydrodynamic size and distribution of Zn ferrite NPs and PEG@Zn ferrite NPs are shown in Figure 6a and Table 4, respectively. The average size of Zn ferrite NPs was measured in the range of 130–150 nm. Zn ferrite NPs had a larger average particle size than PEG@Zn ferrite NPs (80–105 nm) due to a greater tendency toward agglomeration (Figure 6a). DLS measurements for the coating size were conducted three times, and their averages were taken to give consistent information. The sharp peak corresponds to 148 nm for the uncoated NPs and 104 nm for the PEG-coated NPs, which is the dominant particle size distribution in suspension.

Table 4. Zeta Potential, Hydrodynamic Diameter and Polydispersity Index of Zn Ferrite and PEG@Zn Ferrite NPs.

| Sample | Zeta potential (mV) | Mean hydrodynamic diameter (nm) | Polydispersity index (PDI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zn ferrite | –24.5 | 148 | 0.171 |

| PEG@Zn ferrite | –34.6 | 104 | 0.2 |

Figure 6.

(a) Size distribution and (b) zeta potential measurements of Zn ferrite NPs and PEG@Zn ferrite NPs.

Solutes had an average hydrodynamic diameter of 143.72 ± 1.60 nm and a zeta potential of −24.5 mV. The value of the zeta potential suggests that the particles have initial stability in water. Thus, magnetite nanoparticles that are not coated show a modest tendency to aggregate. A polydispersity index of roughly 0.200 implies that the sample is monodisperse. PEG-coating of the Zn ferrite NPs led to a smaller hydrodynamic diameter (103.78 nm), a slightly higher polydispersity index (0.216), and a more stable zeta potential (−34.6 mV) compared to the uncoated Zn ferrite NPs. The stabilizers do not attract each other due to electrostatic repulsion. The negatively charged oxygen atoms in PEG prevent the stacking of polymer layers, resulting in a reduced zeta potential and a more stable colloidal solution. This indicates that the coated sample forms fewer clumps in water than the untreated sample. High charge differences (> ±10 mV) result in increased interparticle repulsion; hence, rising zeta potential values increase colloidal stability. Due to the repetitions of hydrophilic ethylene glycol in the PEG coating, dispersibility in aqueous environments such as water is enhanced.74

Figure 7 depicts the M–H curves of Zn ferrite NPs and PEG-coated Zn ferrite NPs at room temperature in the presence of magnetic fields up to 15000 Oe, obtained by a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM). Table 5 shows that the saturation magnetization of Zn ferrite NPs was greater than that of PEG-coated Zn ferrite NPs. After coating, the saturation magnetization of Zn ferrite NPs dramatically decreased. Since saturation magnetization is proportional to the mass ratio of the magnetic material within the organic layer, it is hypothesized that after capping each particle, the mass fraction of magnetic material decreases, hence reducing the saturation magnetization.75 The magnetic characteristics of Zn ferrite NPs and PEG@Zn ferrite NPs were determined and are presented in Table 5. Both samples exhibited the usual features of superparamagnetic behavior: absence of hysteresis, nearly nonmeasurable coercivity, and remanence. For each of these nanoparticles, these characteristics imply the presence of superparamagnetic and single-domain particles. So, the prepared nanoparticles showed negligible hysteresis and superparamagnetic behavior and a moderate Ms value that tended to achieve enhanced MRI contrast; similar behaviors of ferrite NPs have been reported by other researchers.51,76,77 Therefore, the produced nanoparticles displayed reduced coercivity and remanent magnetization, as well as a superparamagnetic behavior, rendering them ideal for biological applications. High saturation magnetization is one of the most prominent aspects in the effective thermal power generation of NPs. Since magnetic measurements indicate that the coated sample is magnetized, the magnetization is proportional to the mass ratio of the magnetic material deposited within the organic layers.63 Therefore, the presence of a coating layer over magnetic NPs induces a decrease in saturation magnetization, which influences heat generation.78 The percentage of squareness is less than what would be predicted for noninteracting, randomly oriented items, which might be related to the exchange interactions between particles, which influence the magnetic anisotropy of nanopolycrystalline magnetic materials.66

Figure 7.

M–H curves for (a) Zn ferrite NPs and (b) PEG@Zn ferrite NPs.

Table 5. Magnetic Parameters of Zn Ferrite NPs and PEG@Zn Ferrite NPs Obtained from the M–H Curves.

| Samples | Ms (emu/g) | Mr (emu/g) | Hc (Oe) | Mr/Ms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn ferrite NPs | 55 | 13 | <100 | 0.23 |

| PEG@Zn ferrite NPs | 51 | 11 | <100 | 0.21 |

The possible adverse impacts of NP exposure may become a major concern as uses of NPs continue to develop. Understanding the cytotoxicity of NPs to human cell lines is crucial before using them for in vitro or in vivo applications. The fibroblasts have been described as a well-founded resource for in vitro investigations, having considerable benefits over altered cell lines. In addition, they are the most abundant cells in complex organisms. Human normal skin cell lines (HSF 1184) were utilized in this work to examine the cytotoxic potential of the produced PEG@Zn ferrite NPs and Zn ferrite NPs using the MTT test. After 24 h of incubation at several concentrations (0–1000 μg/mL) of Zn ferrite and PEG@Zn ferrite NPs, the percentage of viable cells was determined and is displayed in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Effect of (a) Zn ferrite NPs and (b) PEG@Zn ferrite NPs on the viability of HSF 1184 cells after incubation for 24 h at different concentrations, as evaluated by MTT assay.

Even at 1000 μg/mL concentration, the PEG@Zn ferrite NPs demonstrated no significant cytotoxic impact compared to the control. On the other hand, the cell viability following incubation with Zn ferrite NPs was considerably decreased compared to cells coated with PEG. More than 74% of cell growth was found in the presence of 1000 μg/mL of PEG@Zn ferrite NPs, whereas only 56% of cell survival at the same concentration was reported for Zn ferrite NPs. The results show that as the concentration of Zn ferrite NPs increased above 700 μg/mL, cell proliferation decreased, which could be due to the NPs’ ability to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS). Raised ROS levels can induce mitochondrial malfunction, DNA damage, and protein damage in the cells, leading to the suppression of cell growth and eventually cell death.79 All these data clearly revealed that the cytotoxicity of Zn ferrite NPs was dependent on concentration and exposure period, as has been reported in earlier investigations.80−82 The Zn ferrite NPs were established to be expressively more cytotoxic to HSF-1184 cells as compared to PEG@Zn ferrite NPs, which might be linked with the inherent anticancer characteristic of Zn ferrite NPs.83 In addition, cells treated with PEG@Zn ferrite NPs acquired a considerable viability of approximately 100% at 600 μg/mL concentration and 80% at 900 μg/mL concentration. These results suggest that the biocompatibility of Zn ferrite NPs was significantly enhanced when coated with PEG, as reported elsewhere.84

MRI contrast agents can be either positive or negative, depending on the size of the particles, how they are coated, and how magnetic they are. Zn ferrite and PEG@Zn ferrite NPs could be used as a negative contrast agent to measure T2 MRI relaxation times in this case. The relativities of Zn ferrite NPs and PEG@Zn ferrite NPs as MRI contrast agents were determined using an agar phantom and a clinical MRI (1.5 T).27 When the T2-weighted images in the phantom gels were analyzed, increasing NPs concentrations resulted in discernible darkening and negative contrast (Figure 9a). However, T2-weighted images for PEG@Zn ferrite NPs were stronger due to better dispersion of the NPs due to the polymer coating. The color map along the T2-weighted images displays the various degrees of coated ion concentrations, proving that coated NPs can be a more effective MRI contrast agent.

Figure 9.

(a) T2-weighted MRI images of Zn ferrite and PEG@Zn ferrite NPs at various concentrations. (b) Plot representing the r2 relaxation rate versus Zn ferrite and PEG@Zn ferrite NP concentrations that r2 values calculated from the slopes of the best-fit lines for the experimental data.

Figure 9b was derived from the observed values, which were completely linear with increasing Zn ferrite and PEG@Zn ferrite NP concentrations. The slope was estimated using a linear regression line, and it may be related to the form of the NP since the structure has a comparatively lower surface-to-volume ratio, which leads to fewer hydrogen nuclei interactions in the surrounding water.85

Zn ferrite NPs had a r2 relaxivity of 193 mM–1 s–1, which is comparable with a previous work that utilized a different synthesis route and structure.86 Following the quantum mechanical outer-sphere theory, saturation magnetization has a significant impact on transverse relaxation, and NPs with large Ms have high r2 values.87,88 In agreement with this, PEG@Zn ferrite clusters had a greater r2 of 205 mM–1 s–1. Compared to uncoated nanoparticles, the r2 relaxivity was considerably increased, and it is thought that the amplification of spin–spin relaxation reflects the capacity of magnetic particles to deform the local magnetic field. Some sources claim categorically that size is the decisive factor. For instance, when the particle size is greater than 9 nm and the Ms value is high, the r2 relaxivity will increase due to the aggregation in the suspension. The results show that PEG@Zn ferrite NPs might be employed as a superior T2-shortening agent because of their tiny size and large r2 value. In the T2-weighted MR images, the sample with a short T2 relaxation time (that is, a high r2 value) shows a dark signal. These samples’ T2-weighted phantom imaging confirms the trend of their T2 contrast abilities.

Conclusion

The results indicate that the modification technique affected the final morphology, size, agglomeration degree, and charge of the nanoparticles. PEG-coated zinc ferrite NPs synthesized by the hydrothermal process with ultrasmall size (15 nm), good and homogeneous dispersion (biocompatible and water dispersible), and spherical shape could be extremely desirable for biomedical and clinical applications. FTIR and TEM studies confirmed the coating of the biocompatible PEG polymer. The zeta potential value demonstrated that the coated NPs are more stable than the uncoated NPs, while DLS analysis determined the dispersibility and liquid stability of NPs as a viable choice for biomedical applications. To verify the biocompatibility of the created nanosystem, an in vitro MTT experiment was performed. The cytotoxicity experiments conducted on HSF 1184 cell lines revealed that NPs exhibited a substantial dosage advantage over uncoated NPs, and the coated synthetic NPs were nontoxic, making them an excellent contender for biomedical applications. The PEG@Zn ferrite NPs demonstrate significant potential in MRI, and the current production and assessment procedures for the NPs might be applied to produce other types of magnetic NPs. Furthermore, in terms of NP concentration in aqueous solutions, PEG@Zn ferrite NPs had a high r2 relaxivity (205 mM–1 s–1). Further studies should be conducted to determine whether ferrite-based NPs of other shapes or coating materials may also be used as T2 contrast agents.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by 2232 International Fellowship for Outstanding Researchers Program of TÜBİTAK (Project No. 118C346).

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm the absence of sharing data.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Li X.; Wei J.; Aifantis K. E.; Fan Y.; Feng Q.; Cui F. Z.; Watari F. Current investigations into magnetic nanoparticles for biomedical applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A 2016, 104 (5), 1285–1296. 10.1002/jbm.a.35654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed L.; Gomaa H. G.; Ragab D.; Zhu J. Magnetic nanoparticles for environmental and biomedical applications: A review. Particuology 2017, 30, 1–14. 10.1016/j.partic.2016.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavi M.; Ahmad M. B.; Haron M. J.; Namvar F.; Nadi B.; Rahman M. Z. A.; Amin J. Synthesis, surface modification and characterisation of biocompatible magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Molecules 2013, 18 (7), 7533–7548. 10.3390/molecules18077533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson J. Magnetic nanoparticles for drug delivery. Drug Dev. Res. 2006, 67 (1), 55–60. 10.1002/ddr.20067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tassa C.; Shaw S. Y.; Weissleder R. Dextran-coated iron oxide nanoparticles: a versatile platform for targeted molecular imaging, molecular diagnostics, and therapy. Accounts of chemical research 2011, 44 (10), 842–852. 10.1021/ar200084x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou P.; Yu Y.; Wang Y. A.; Zhong Y.; Welton A.; Galbán C.; Wang S.; Sun D. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanotheranostics for targeted cancer cell imaging and pH-dependent intracellular drug release. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2010, 7 (6), 1974–1984. 10.1021/mp100273t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertas Y. N.; Abedi Dorcheh K.; Akbari A.; Jabbari E. Nanoparticles for Targeted Drug Delivery to Cancer Stem Cells: A Review of Recent Advances. Nanomaterials 2021, 11 (7), 1755. 10.3390/nano11071755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C.; Lee J. S.; Zhang M. Magnetic nanoparticles in MR imaging and drug delivery. Advanced drug delivery reviews 2008, 60 (11), 1252–1265. 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertas Y. N.; Jarenwattananon N. N.; Bouchard L. S. Oxide-Free Gadolinium Nanocrystals with Large Magnetic Moments. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27 (15), 5371–5376. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b01995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T.; Lin M.; Huang J.; Zhou C.; Tian W.; Yu H.; Jiang X.; Ye J.; Shi Y.; Xiao Y. The recent advances of magnetic nanoparticles in medicine. J. Nanomater. 2018, 2018, 7805147. 10.1155/2018/7805147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nosrati H.; Ghaffarlou M.; Salehiabar M.; Mousazadeh N.; Abhari F.; Barsbay M.; Ertas Y. N.; Rashidzadeh H.; Mohammadi A.; Nasehi L.; et al. Magnetite and bismuth sulfide Janus heterostructures as radiosensitizers for in vivo enhanced radiotherapy in breast cancer. Biomater Adv. 2022, 140, 213090. 10.1016/j.bioadv.2022.213090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mornet S.; Vasseur S.; Grasset F.; Duguet E. Magnetic nanoparticle design for medical diagnosis and therapy. J. Mater. Chem. 2004, 14 (14), 2161–2175. 10.1039/b402025a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dadfar S. M.; Roemhild K.; Drude N. I.; von Stillfried S.; Knüchel R.; Kiessling F.; Lammers T. Iron oxide nanoparticles: Diagnostic, therapeutic and theranostic applications. Advanced drug delivery reviews 2019, 138, 302–325. 10.1016/j.addr.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosrati H.; Salehiabar M.; Mozafari F.; Charmi J.; Erdogan N.; Ghaffarlou M.; Abhari F.; Danafar H.; Ramazani A.; Ertas Y. N. Preparation and evaluation of bismuth sulfide and magnetite-based theranostic nanohybrid as drug carrier and dual MRI/CT contrast agent. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2022, 36 (11), e6861. 10.1002/aoc.6861. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H.; Tan T.; Cheng L.; Liu J.; Song H.; Li L.; Zhang K. MRI tracing of ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle-labeled endothelial progenitor cells for repairing atherosclerotic vessels in rabbits. Molecular Medicine Reports 2020, 22 (4), 3327–3337. 10.3892/mmr.2020.11431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary R.; Roy K.; Kanwar R. K.; Walder K.; Kanwar J. R. Engineered atherosclerosis-specific zinc ferrite nanocomplex-based MRI contrast agents. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2016, 14 (1), 6. 10.1186/s12951-016-0157-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S.-N.; Wei C.; Zhu Z.-Z.; Hou Y.-L.; Venkatraman S. S.; Xu Z.-C. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: Synthesis and surface coating techniques for biomedical applications. Chinese Physics B 2014, 23 (3), 037503. 10.1088/1674-1056/23/3/037503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shokrollahi H. Contrast agents for MRI. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2013, 33 (8), 4485–4497. 10.1016/j.msec.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. H.; Kim B. H.; Na H. B.; Hyeon T. Paramagnetic inorganic nanoparticles as T1MRI contrast agents. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2014, 6 (2), 196–209. 10.1002/wnan.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Q.; Lam M.; Swanson S.; Yu R.-H. R.; Milliron D. J.; Topuria T.; Jubert P.-O.; Nelson A. Monodisperse cobalt ferrite nanomagnets with uniform silica coatings. Langmuir 2010, 26 (22), 17546–17551. 10.1021/la103042q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakil M. S.; Hasan M. A.; Uddin M. F.; Islam A.; Nahar A.; Das H.; Khan M. N. I.; Dey B. P.; Rokeya B.; Hoque S. M. In vivo toxicity studies of chitosan-coated cobalt ferrite nanocomplex for its application as MRI contrast dye. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2020, 3 (11), 7952–7964. 10.1021/acsabm.0c01069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy G. K.; Boolchand P.; Smirniotis P. G. Unexpected Behavior of Copper in Modified Ferrites during High Temperature WGS Reaction · Aspects of Fe3+↔ Fe2+ Redox Chemistry from Mössbauer and XPS Studies. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116 (20), 11019–11031. 10.1021/jp301090d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan G.; Tong J.; Li F. Visible-light-induced photocatalyst based on cobalt-doped zinc ferrite nanocrystals. Industrial & engineering chemistry research 2012, 51 (42), 13639–13647. 10.1021/ie201933g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fantechi E.; Innocenti C.; Zanardelli M.; Fittipaldi M.; Falvo E.; Carbo M.; Shullani V.; Di Cesare Mannelli L.; Ghelardini C.; Ferretti A. M.; et al. A smart platform for hyperthermia application in cancer treatment: cobalt-doped ferrite nanoparticles mineralized in human ferritin cages. ACS Nano 2014, 8 (5), 4705–4719. 10.1021/nn500454n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo A.; Pelaz B.; Gallo J.; Banobre-Lopez M.; Parak W. J.; Barbosa S.; del Pino P.; Taboada P. Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of superparamagnetic doped ferrites as potential therapeutic nanotools. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32 (6), 2220–2231. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b04848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Ma L.; Xin J.; Li A.; Sun C.; Wei R.; Ren B. W.; Chen Z.; Lin H.; Gao J. Composition tunable manganese ferrite nanoparticles for optimized T 2 contrast ability. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29 (7), 3038–3047. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b00035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.; Ma S.; Sun J.; Xia C.; Liu C.; Wang Z.; Zhao X.; Gao F.; Gong Q.; Song B.; et al. Manganese ferrite nanoparticle micellar nanocomposites as MRI contrast agent for liver imaging. Biomaterials 2009, 30 (15), 2919–2928. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernia Leal M.; Rivera-Fernández S.; Franco J. M.; Pozo D.; de la Fuente J. M.; García-Martín M. L. Long-circulating PEGylated manganese ferrite nanoparticles for MRI-based molecular imaging. Nanoscale 2015, 7 (5), 2050–2059. 10.1039/C4NR05781C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraji S.; Dini G.; Zahraei M. Polyethylene glycol-coated manganese-ferrite nanoparticles as contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 475, 137–145. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2018.11.097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J.; Zhang Y.; Yan C.; Song L.; Wen S.; Zang F.; Chen G.; Ding Q.; Yan C.; Gu N. High-performance PEGylated Mn–Zn ferrite nanocrystals as a passive-targeted agent for magnetically induced cancer theranostics. Biomaterials 2014, 35 (33), 9126–9136. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lickmichand M.; Shaji C. S.; Valarmathi N.; Benjamin A. S.; Kumar R. A.; Nayak S.; Saraswathy R.; Sumathi S.; Raj N. A. N. In vitro biocompatibility and hyperthermia studies on synthesized cobalt ferrite nanoparticles encapsulated with polyethylene glycol for biomedical applications. Materials Today: Proceedings 2019, 15, 252–261. 10.1016/j.matpr.2019.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mokhosi S.; Mdlalose W.; Mngadi S.; Singh M.; Moyo T. Assessing the structural, morphological and magnetic properties of polymer-coated magnesium-doped cobalt ferrite (CoFe2O4) nanoparticles for biomedical application. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2019, 1310, 012014. 10.1088/1742-6596/1310/1/012014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheraghali S.; Dini G.; Caligiuri I.; Back M.; Rizzolio F. PEG-Coated MnZn Ferrite Nanoparticles with Hierarchical Structure as MRI Contrast Agent. Nanomaterials-Basel 2023, 13 (3), 452. 10.3390/nano13030452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A.; Blasiak B.; Pasquier E.; Tomanek B.; Trudel S. Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of PEGylated first-row transition metal ferrite nanoparticles as T 2 contrast agents for high-field MRI. RSC Adv. 2017, 7 (61), 38125–38134. 10.1039/C7RA05495E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaiselvan C. R.; Thorat N. D.; Sahu N. K. Carboxylated PEG-functionalized MnFe2O4 nanocubes synthesized in a mixed solvent: Morphology, magnetic properties, and biomedical applications. ACS omega 2021, 6 (8), 5266–5275. 10.1021/acsomega.0c05382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorat N. D.; Bohara R. A.; Malgras V.; Tofail S. A.; Ahamad T.; Alshehri S. M.; Wu K. C.-W.; Yamauchi Y. Multimodal superparamagnetic nanoparticles with unusually enhanced specific absorption rate for synergetic cancer therapeutics and magnetic resonance imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8 (23), 14656–14664. 10.1021/acsami.6b02616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan N.; Madni A.; Khan S.; Shah H.; Akram F.; Khan A.; Ertas D.; Bostanudin M. F.; Contag C. H.; Ashammakhi N.; et al. Biomimetic cell membrane-coated poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Bioeng. Transl Med. 2023, 8, e10441. 10.1002/btm2.10441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yallapu M. M.; Foy S. P.; Jain T. K.; Labhasetwar V. PEG-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for drug delivery and magnetic resonance imaging applications. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27 (11), 2283–2295. 10.1007/s11095-010-0260-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafizadeh M.; Zarrabi A.; Karimi-Maleh H.; Taheriazam A.; Mirzaei S.; Hashemi M.; Hushmandi K.; Makvandi P.; Nazarzadeh Zare E.; Sharifi E.; et al. (Nano)platforms in bladder cancer therapy: Challenges and opportunities. Bioeng Transl Med. 2023, 8, e10353. 10.1002/btm2.10353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aisida S. O.; Ahmad I.; Ezema F. I. Effect of calcination on the microstructural and magnetic properties of PVA, PVP and PEG assisted zinc ferrite nanoparticles. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2020, 579, 411907. 10.1016/j.physb.2019.411907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S.; Shinde T. J.; Vasambekar P. N. Microwave synthesis and characterization of nanocrystalline Mn-Zn ferrites. Advanced Materials Letters 2013, 4 (5), 373–377. 10.5185/amlett.2012.10429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sudheesh V.; Thomas N.; Roona N.; Baghya P.; Sebastian V. Synthesis, characterization and influence of fuel to oxidizer ratio on the properties of spinel ferrite (MFe2O4, M= Co and Ni) prepared by solution combustion method. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43 (17), 15002–15009. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.08.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vergés M. A.; Martinez M.; Matijevié E. Synthesis and characterization of zinc ferrite particles prepared by hydrothermal decomposition of zinc chelate solutions. Journal of Materials Research 1993, 8 (11), 2916–2920. 10.1557/JMR.1993.2916. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Wang Y.; Liu B.; Wang J.; Han G.; Zhang Y. Characterization and property of magnetic ferrite ceramics with interesting multilayer structure prepared by solid-state reaction. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47 (8), 10927–10939. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.12.212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gul I.; Maqsood A. Structural, magnetic and electrical properties of cobalt ferrites prepared by the sol–gel route. J. Alloys Compd. 2008, 465 (1–2), 227–231. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2007.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dabagh S.; Haris S. A.; Ertas Y. N. Synthesis, Characterization and Potent Antibacterial Activity of Metal-Substituted Spinel Ferrite Nanoparticles. J. Clust Sci. 2022, 10.1007/s10876-022-02373-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gul I.; Ahmed W.; Maqsood A. Electrical and magnetic characterization of nanocrystalline Ni–Zn ferrite synthesis by co-precipitation route. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2008, 320 (3–4), 270–275. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2007.05.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa N. Y.; Hessien M.; Shaltout A. A. Hydrothermal synthesis and characterizations of Ti substituted Mn-ferrites. Journal of alloys and compounds 2012, 529, 29–33. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2012.03.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Praveena K.; Sadhana K.; Virk H. S. Structural and magnetic properties of Mn-Zn ferrites synthesized by microwave-hydrothermal process. Solid State Phenomena 2015, 232, 45–64. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/SSP.232.45. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Starsich F. H.; Sotiriou G. A.; Wurnig M. C.; Eberhardt C.; Hirt A. M.; Boss A.; Pratsinis S. E. Silica-Coated Nonstoichiometric Nano Zn-Ferrites for Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Hyperthermia Treatment. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2016, 5 (20), 2698–2706. 10.1002/adhm.201600725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali R.; Aziz M. H.; Gao S.; Khan M. I.; Li F.; Batool T.; Shaheen F.; Qiu B. Graphene oxide/zinc ferrite nanocomposite loaded with doxorubicin as a potential theranostic mediu in cancer therapy and magnetic resonance imaging. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48 (8), 10741–10750. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.12.290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M. A.; Hasan M. R.; Haque M. M.; Rashid R.; Syed I. M.; Hoque S. M. Efficacy of surface-functionalized Mg 1– x Co x Fe 2 O 4 (0≤ x≤ 1; Δ x= 0.1) for hyperthermia and in vivo MR imaging as a contrast agent. RSC Adv. 2022, 12 (13), 7835–7849. 10.1039/D2RA00768A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachowicz D.; Stroud J.; Hankiewicz J. H.; Gassen R.; Kmita A.; Stepien J.; Celinski Z.; Sikora M.; Zukrowski J.; Gajewska M.; et al. One-Step Preparation of Highly Stable Copper–Zinc Ferrite Nanoparticles in Water Suitable for MRI Thermometry. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34 (9), 4001–4018. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.2c00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath C.; Mishra N.; Anand S.; Das R.; Sahu K.; Upadhyay C.; Verma H. Appearance of superparamagnetism on heating nanosize Mn 0.65 Zn 0.35 Fe 2 O 4. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000, 76 (4), 475–477. 10.1063/1.125792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver S.; Harris V.; Hamdeh H.; Ho J. Large zinc cation occupancy of octahedral sites in mechanically activated zinc ferrite powders. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000, 76 (19), 2761–2763. 10.1063/1.126467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qin M.; Shuai Q.; Wu G.; Zheng B.; Wang Z.; Wu H. Zinc ferrite composite material with controllable morphology and its applications. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2017, 224, 125–138. 10.1016/j.mseb.2017.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chavan S.; Mane S.; Kulkarni S.; Jayasingh M.; Joshi P.; Salunkhe D. Micro-wave sintered nickel doped cobalt ferrite nanoparticles prepared by hydrothermal method. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics 2016, 27 (7), 7105–7108. 10.1007/s10854-016-4672-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna L.; Verma N. K. Synthesis, characterization and in vitro cytotoxicity study of calcium ferrite nanoparticles. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 2013, 16 (6), 1842–1848. 10.1016/j.mssp.2013.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna L.; Gupta G.; Tripathi S. Effect of size and silica coating on structural, magnetic as well as cytotoxicity properties of copper ferrite nanoparticles. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2019, 97, 552–566. 10.1016/j.msec.2018.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattarahmady N.; Zare T.; Mehdizadeh A.; Azarpira N.; Heidari M.; Lotfi M.; Heli H. Dextrin-coated zinc substituted cobalt-ferrite nanoparticles as an MRI contrast agent: in vitro and in vivo imaging studies. Colloids Surf., B 2015, 129, 15–20. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahane G.; Kumar A.; Arora M.; Pant R.; Lal K. Synthesis and characterization of Ni–Zn ferrite nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2010, 322 (8), 1015–1019. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2009.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kareem S. H.; Ati A. A.; Shamsuddin M.; Lee S. L. Nanostructural, morphological and magnetic studies of PEG/Mn (1– x) Zn (x) Fe2O4 nanoparticles synthesized by co-precipitation. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41 (9), 11702–11709. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2015.05.134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zargar T.; Kermanpur A.; Labbaf S.; Houreh A. B.; Esfahani M. N. PEG coated Zn0.3Fe2.7O4 nanoparticles in the presence of <alpha>Fe2O3 phase synthesized by citric acid assisted hydrothermal reduction process for magnetic hyperthermia applications. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 212, 432–439. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2018.03.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi M.; Kameli P.; Ranjbar M.; Salamati H. The effect of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) coating on structural, magnetic properties and spin dynamics of Ni0.3Zn0.7Fe2O4 ferrite nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2013, 347, 139–145. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2013.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehi-Eromosele C. O.; Ita B. I.; Iweala E. E. J. The effect of polyethylene glycol (PEG) coating on the magneto-structural properties and colloidal stability of CO0.8Mg0.2Fe2O4 nanoparticles for potential biomedical applications. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2016, 11, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Dabagh S.; Ati A. A.; Rosnan R. M.; Zare S.; Othaman Z. Effect of Cu–Al substitution on the structural and magnetic properties of Co ferrites. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 2015, 33, 1–8. 10.1016/j.mssp.2015.01.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deswardani F.; Maulia R.; Suharyadi E. Study of structural and magnetic properties of silica and polyethylene glycol (PEG-4000)-encapsulated magnesium nickel ferrite (Mg0.5Ni0.5Fe2O4) nanoparticles. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2017, 202, 012047. 10.1088/1757-899X/202/1/012047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar P.; Ramesh R.; Ramanand A.; Ponnusamy S.; Muthamizhchelvan C. Synthesis and characterization of nickel ferrite magnetic nanoparticles. Mater. Res. Bull. 2011, 46 (12), 2208–2211. 10.1016/j.materresbull.2011.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phadatare M. R.; Khot V.; Salunkhe A.; Thorat N.; Pawar S. Studies on polyethylene glycol coating on NiFe2O4 nanoparticles for biomedical applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2012, 324 (5), 770–772. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2011.09.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi M.; Ezazi M.; Jouyban A.; Lulek E.; Asadpour-Zeynali K.; Ertas Y. N.; Houshyar J.; Mokhtarzadeh A.; Soleymani J. An ultrasensitive and preprocessing-free electrochemical platform for the detection of doxorubicin based on tryptophan/polyethylene glycol-cobalt ferrite nanoparticles modified electrodes. Microchemical Journal 2022, 183, 108055. 10.1016/j.microc.2022.108055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naseri M. G.; Saion E. B.; Ahangar H. A.; Shaari A. H. Fabrication, characterization, and magnetic properties of copper ferrite nanoparticles prepared by a simple, thermal-treatment method. Mater. Res. Bull. 2013, 48 (4), 1439–1446. 10.1016/j.materresbull.2012.12.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mallick A.; Mahapatra A.; Mitra A.; Greneche J.-M.; Ningthoujam R.; Chakrabarti P. Magnetic properties and bio-medical applications in hyperthermia of lithium zinc ferrite nanoparticles integrated with reduced graphene oxide. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 123 (5), 055103. 10.1063/1.5009823. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Routray K. L.; Saha S.; Behera D. Effect of CNTs blending on the structural, dielectric and magnetic properties of nanosized cobalt ferrite. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2017, 226, 199–205. 10.1016/j.mseb.2017.09.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorospe A.; Buenviaje S.; Edañol Y.; Cervera R.; Payawan L. One-Step Co-Precipitation Synthesis of Water-Stable Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Coated Magnetite Nanoparticles. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2019, 1191, 012059. 10.1088/1742-6596/1191/1/012059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ertas Y. N.; Bouchard L. S. Controlled nanocrystallinity in Gd nanobowls leads to magnetization of 226 emu/g. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 121 (9), 093902. 10.1063/1.4977511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur S.; Katyal S. C.; Singh M. Structural and magnetic properties of nano nickel–zinc ferrite synthesized by reverse micelle technique. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2009, 321 (1), 1–7. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2008.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gharibshahian M.; Mirzaee O.; Nourbakhsh M. S. Evaluation of superparamagnetic and biocompatible properties of mesoporous silica coated cobalt ferrite nanoparticles synthesized via microwave modified Pechini method. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 425, 48–56. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2016.10.116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodarz Naseri M.; Saion E. B.; Abbastabar Ahangar H.; Shaari A. H.; Hashim M. Simple synthesis and characterization of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles by a thermal treatment method. J. Nanomater. 2010, 2010, 907686. 10.1155/2010/907686. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M.; Li Y.; Lin Z.; Zhao M.; Xiao M.; Wang C.; Xu T.; Xia Y.; Zhu B. Surface decoration of selenium nanoparticles with curcumin induced HepG2 cell apoptosis through ROS mediated p53 and AKT signaling pathways. RSC Adv. 2017, 7 (83), 52456–52464. 10.1039/C7RA08796A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T.; Dou F.; Lin M.; Huang J.; Zhou C.; Zhang J.; Yu H.; Jiang X.; Ye J.; Shi Y. Biological characteristics and carrier functions of pegylated manganese zinc ferrite nanoparticles. J. Nanomater. 2019, 2019, 6854710. 10.1155/2019/6854710. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sobhani T.; Shahbazi-Gahrouei D.; Rostami M.; Zahraei M.; Farzadniya A. Assessment of manganese-zinc ferrite nanoparticles as a novel magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent for the detection of 4T1 breast cancer cells. Journal of Medical Signals and Sensors 2019, 9 (4), 245. 10.4103/jmss.JMSS_59_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. Q.; Yin L. H.; Meng T.; Pu Y. P. ZnO, TiO2, SiO2, and Al2O3 nanoparticles-induced toxic effects on human fetal lung fibroblasts. Biomedical and Environmental Sciences 2011, 24 (6), 661–669. 10.3967/0895-3988.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alshahrani B.; ElSaeedy H.; Fares S.; Korna A.; Yakout H.; Ashour A.; Fahim R. A.; Kodous A. S.; Gobara M.; Maksoud M. Structural, optical, and magnetic properties of nanostructured Ag-substituted Co-Zn ferrites: insights on anticancer and antiproliferative activities. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics 2021, 32 (9), 12383–12401. 10.1007/s10854-021-05870-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chi Y.; Yuan Q.; Li Y.; Tu J.; Zhao L.; Li N.; Li X. Synthesis of Fe3O4@SiO2–Ag magnetic nanocomposite based on small-sized and highly dispersed silver nanoparticles for catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 383 (1), 96–102. 10.1016/j.jcis.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Liu J.; Li T.; Liu J.; Wang B. Controlled synthesis of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles and Gd complex-based nanocomposites as tunable and enhanced T1/T2-weighted MRI contrast agents. J .Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 4748–4753. 10.1039/c4tb00342j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Sun C.; Lin H.; Gong X.; Zhou T.; Deng W.-T.; Chen Z.; Gao J. Sensitive contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of orthotopic and metastatic hepatic tumors by ultralow doses of zinc ferrite octapods. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31 (4), 1381–1390. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b04760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis P.; Moiny F.; Brooks R. A. On T2-shortening by strongly magnetized spheres: a partial refocusing model. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2002, 47 (2), 257–263. 10.1002/mrm.10059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun Y.-w.; Seo J.-w.; Cheon J. Nanoscaling laws of magnetic nanoparticles and their applicabilities in biomedical sciences. Accounts of Chemical Research 2008, 41 (2), 179–189. 10.1021/ar700121f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm the absence of sharing data.