Abstract

Introduction

Cancer metastasis is associated with increased cancer incidence, recurrence, and mortality. The role of cell contact guidance behaviors in cancer metastasis has been recognized but has not been elucidated yet.

Methods

The contact guidance behavior of cancer cells in response to topographical constraints is identified using microgrooved substrates with varying dimensions at the mesoscopic scale. Then, the cell morphology is determined to quantitatively analyze the effects of substrate dimensions on cells contact guidance. Cell density and migrate velocity signatures within the cellular population are determined using time-lapse phase-contrast microscopy. The effect of soluble factors concentration is determined by culturing cells upside down. Then, the effect of cell-substrate interaction on cell migration is investigated using traction force microscopy.

Results

With increasing depth and decreasing groove width, cell elongation and alignment are enhanced, while cell spreading is inhibited. Moreover, cells display preferential distribution on the ridges, which is found to be more pronounced with increasing depth and groove width. Determinations of cell density and migration velocity signatures reveal that the preferential distribution on ridges is caused by cell upward migration. Combined with traction force measurement, we find that migration toward ridges is governed by different cell-substrate interactions between grooves and ridges caused by geometrical constraints. Interestingly, the upward migration of cells at the mesoscopic scale is driven by entropic maximization.

Conclusions

The mesoscopic cell contact guidance mechanism based on the entropic force driven theory provides basic support for the study of cell alignment and migration along healthy tissues with varying size, thereby aiding in the prediction of cancer metastasis.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12195-023-00766-y.

Keywords: Topographical features, Contact guidance, Cell-substrate adhesion, Cell migration, Mesoscopic scale

Introduction

Extracellular microenvironments of cancer cells composed of abundant chemical and physical cues, have been proven to influence various cell behaviors.1–3 Although early works have emphasized the role of chemical gradients, it is becoming evident that the topography of the matrix plays an important role in cell polarization, alignment and migration, which is called contact guidance.4–6 Recently, with the development of fabrication techniques, various topographical patterns (e.g., pillars, pits/walls and grooves)7–10 have been obtained to study the contact guidance effects.11–13 Most studies imply that cancer cell behavior is affected by the topography with a size close to the size of ECM fibers.11 Nevertheless, a growing number of evidence shows that cancer cells migration along or within interstitial space and vasculature at the mesoscopic scale (10–100 μm) plays a vital role in cancer metastasis.14–16 However, the role and mechanism of mesoscopic topographical cues in cell contact guidance behavior have not been clearly understood.

There exists mounting evidence that cells have the remarkable ability to sense and react to topographical cues due to contact guidance. The most widely accepted model for contact guidance mechanism is the focal adhesions (FAs) based model. This model assumes that anisotropic topographic features impose lateral constraints on the formation of FAs and actin stress fibers, which drive the generation of anisotropic forces and result in the elongation and alignment of cells.10,17–19 Nevertheless, Buskermolen et al. find that when the topological structure size increases to a mesoscopic scale, the FAs based model cannot explain various behaviors of the cells.20,21 Thus, they propose an alternative mechanism of contact guidance based on entropic force driven theory.20 The entropic force driven theory indicates that the topological constraints with dimensions larger than cell size will result in a maximization of morphological entropy. Therefore, the alignment of the cells is driven by entropic force related to the fluctuation of cell morphology.20 Although numerous studies have extensively explored cell morphology and orientation in response to topological patterns, there are still few researches on cell migration behaviors at the mesoscopic scale due to contact guidance, which is essential for cancer metastasis.

As the essence of contact guidance, cell-substrate adhesion plays an important role in cell migration. The driving force of cell motility induced by cell-substrate adhesion is called traction force.22 Large traction force always offers greater potential for cell migration, while asymmetric traction force drives cells to migrate directionally.23,24 Methods for measuring cellular traction force are mainly based on collagen contraction, micropillars and traction force microscopy (TFM).9,22,24,25 Among them, TFM is widely used for the quantitative characterization of cell-substrate adhesion due to its high resolution.26,27 Two-dimensional (2D) TFM is mainly used for the characterization of cell traction force on a flat surface, while three-dimensional (3D) TFM is usually used to measure the 3D traction field of cells using layer-by-layer scanning.25,27,28 2.5D TFM enables characterization of the 3D traction field of cells cultured on a 2D substrate, which is suitable for traction force determination for substrates with two dominate surfaces, such as microgrooves.24,29

Herein, a series of PAAm micropatterned substrates (100 μm in ridge width) with varying groove widths (25, 50 and 100 μm) and depths (5, 15 and 30 μm) are prepared using soft lithography to investigate the mesoscopic contact guidance behaviors of the MDA-MB-231 cells. Interestingly, cell elongation and alignment are enhanced with increasing depth and decreasing groove width, but cell spreading is inhibited. Besides, cells display a clear trend to gather on the ridges, which becomes more pronounced with the increasing depth and groove width. Comprehensive analysis of the density and migration velocity of cells on ridges and grooves implies that the preferential spatial distribution is caused by cell upward migration. By culturing cells upside down, we find that dissolved soluble factors concentration is not the dominant reason for upward migration, while the cell-substrate adhesion has a great influence on upward migration. Moreover, TFM is used to quantify the traction force of MDA-MB-231 cells to determine the cell-substrate interaction. The force fields of MDA-MB-231cells always direct toward the ridges, indicating that the cell-substrate interaction caused by contact guidance plays a guiding role in the cell upward migration. Based on the determination of cell morphology, migration and cell-substrate interaction, we hypothesize that the ridge aggregation of cells is caused by entropy-driven upward migration at the mesoscopic scale. This study is original because we systematically investigate the contact guidance response of cancer cells to mesoscopic topological features and reveal the mesoscopic cell contact guidance mechanism. The mechanism based on entropic force driven theory provides a new idea for studies in regulating normal or cancer cell behaviors, which contributes to research in cancer metastasis and clinical anti-cancer drug development.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Master Substrates

The master substrates with microgrooves were fabricated as shown in Fig. 1A. Firstly, 500 nm thick silicon dioxide was deposited on a silicon wafer using plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD). Then, AZ6112 photoresist with a thickness of 1 μm was spin coated on silicon dioxide and patterned using lithography with UV exposure for 2 s after baking at 95 °C for 60 s. After that, the silicon dioxide was patterned by reactive ion etching (RIE). Using silicon dioxide as a sacrificial layer, the master substrates consisted of an array of parallel ridges with variable depths (5, 15 and 30 μm) and variable groove widths (25 μm, 50 μm and100 μm), and a constant ridge width (100 μm) were fabricated by induction coupling plasma (ICP).

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the substrate fabrication and cell seeding. A The fabrication process of microgrooved silicon molds by conventional lithography. Firstly, SiO2 was etched using Reactive ion etching (RIE) under the protection of the patterned photoresist layer. Then, the microgrooved substrates was formed after Si etching using inductive coupling plasma etching (ICP). The polyacrylamide (PAAm) substrates with negative microgrooves were generated using soft lithography. After that, fluorescence beads were embedded in functionalized PAAm substrates to determination cell traction located on microgrooved substrates. B Geometry dimensions of microgrooved silicon molds measured by profilometer. C Micrographs of microgrooved PAAm substrate. D Fluorescence image of MDA-MB-231cells cultured on microgrooved PAAm substrate. White scale bars equal100 μm

Preparation of PAAm Substrates

In brief, the coverslip was first immersed in 0.1 M NaOH for 24 h, then treated with 0.5% (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APES, Sangon Biotech, China) followed by treatment with 0.5% glutaraldehyde (Sigma Aldrich, China) solution. Polyacrylamide (PAAm) gel preparation has been adapted as reported previously (Aratyn-Schaus et al., 2010). The polyacrylamide mixture contained 5% (w/v) acrylamide (Sigma Aldrich, China), 1.5% (w/v) bis-acrylamide (Sigma Aldrich, China) and 0.1% (w/v) ammonium persulfate (APS, Sangon Biotech, China) was prepared with Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, HyClone, USA) as solvent. Then, 0.5 µl of N,N,N',N'-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED, Sigma Aldrich, China) was added to each 1 ml of acrylamide mixture solution and mixed briefly. The mixture of the reaction solution was then pipetted between the master substrate and a coverslip immediately, formed a sandwich and gelled at room temperature for 10 min. Finally, the PAAm was peeled off and immersed in PBS at 4 °C for use.

Substrate Functionalization

To promote cell adhesion, collagen (Sigma Aldrich, China) was covalently linked to the PAAm substrates. Briefly, 180 μl of the 0.5 mg/ml sulfo-SANPAH (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) solution was pipetted onto the gel (12 × 12 mm) and immediately exposed to 365 nm UV light for 10 min. The UV-treated substrate was dipped in a baker with fresh distilled H2O to remove unbound sulfo-SANPAH, and incubated with 0.01% collagen solution at 4 °C overnight. Finally, the substrate was sterilized by a germicidal lamp in biosafety cabinet for 30 min and incubated in cell culture medium for 30 min to plate cells.

Dimension and Stiffness Determination of PAAm Substrates

To determine the dimensions of silicon molds and PAAm substrates, samples were immersed in PBS and the sizes were measured by a 3D Optical Profiling system (Contour GT-K, Bruker, Germany) through 3D scanning, and the dimensions were recorded (Table S2).

The stiffness of the PAAm substrates in this study was investigated using an atomic force microscope (AFM, Bruker Resolve8, USA). The samples were maintained in a liquid environment and measured using a probe with a 1 µm-radius ball as the tip (Bruker, ScanAsyst-Fluid + , USA). To calculate the Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio was set as 0.5 based on previous studies.30,31 Then, the force–displacement curve was collected and fitted to the Hertz sphere model (Figure S2).

Cell Culture

MDA-MB -231 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 Medium (Gibco, USA) containing 5% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, HyClone, USA), 0.004% (w/v) Gentamycin (Sangon Biotech, China) and 1% penicillin/ streptomycin antibiotics (Gibco, USA). The cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in 60 mm dishes. Then, PAAm samples were placed in 35 mm dishes and the cells were seeded at a density of 1.8 × 104 cells/cm2. Cells were allowed to adhere to the substrate for at least 2 h before the inspection every other day for a total of 4 days.

To determine the effect of soluble factors concentration on cell spatial distribution, cells were cultured upside down on an inverted substrate. The standard coverslips with a thickness of about 170 ± 20 μm were placed on each side of the inverted substrate. The gap between the substrate and the bottom of the culture dish is much larger than the cell size, so cells can pass through.

To investigate the effect of cell-substrate adhesion on contact guidance, the Blebbistatin stock solution (Sigma Aldrich, China) dissolved in DMSO (Sigma Aldrich, China) was removed from the − 80 °C freezer and diluted to a 20 μM working solution using culture medium. Then, the culture medium was changed with Blebbistatin solution at different culture times to inhibit myosin II formation.

Immunofluorescence Staining and Cell Morphology Determination

Firstly, samples were washed three times with PBS to remove the culture medium. Then, MDA-MB-231 cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 15 min and washed three times with DPBS, then permeated with 0.5% Triton X-100 solution for another 15 min. After being washed with DPBS for three times, samples were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Invitrogen, USA) in DPBS at room temperature for 1 h. Later, cells were stained with 5 mg/ml of rhodamine phalloidin (Invitrogen, USA) for 1 h and 50 mg/ml DAPI (Invitrogen, USA) for 10 min at room temperature in dark to visualize F-actin (red) and cell nuclei (blue), respectively. The cells were imaged using fluorescence microscopy (Leica DMI 3000b, Germany).

For the analysis of the cell morphology, Fiji/ImageJ was used to fit the cell contour to an ellipse. Then, the results were quantified by analyzing the area and aspect ratio of cell contours. The cell orientation angle is defined as the angle between the long axis of the cell contours and the microgrooves.32 Alignment angles of cells were categorized from 0° to 90° in 10° increments and the orientation angle frequency was quantified. Besides, the order parameter is calculated as follows:

When the cell orientation is parallel to the groove direction, θ approaches 0° and OP approaches 1; when the cell orientation is perpendicular to the groove direction, θ approaches 90° and OP approaches − 0.5; when OP approaches 0, which means that the cell orientation is independent of the groove direction, and the cell orientation is random.

Determination of Spatial Distribution and Mobility of Cells

The cell density in the grooves and ridges is obtained by counting cells in different parts of the substrates and dividing by area. The R/G ratio is defined as the ratio of cell density at the ridges and grooves of microgrooves.

Cell moving path with its migration speed was measured by time-lapse microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 200 M) for 20 different cells after 48 h of culture. The figures were captured every 10 min up to 28.5 h. The moving path of cells was tracked with the plugin Mtrackj of Fiji/ImageJ software.

TFM Substrates Preparation and Traction Force Measurements

For the TFM experiments, the substrates were made as previously described.33 Firstly, the PAAm substrates were immersed into the solution containing 0.025 mg/ml red fluorescent carboxylate-modified latex beads with 500 nm diameter (575/610, Sigma Aldrich, USA) for 45 min. Then, rinsed with distilled H2O to remove excess beads. After that, the PAAm substrates were treated with 3.8 mg/ml 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDAC) (Sangon Biotech, China) followed by treatment with 7.6 mg/ml N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (Sulfo-NHS) (Sangon Biotech, China) solution for 2 h, respectively. Also, the EDAC solution was prepared in 2-(N-Morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES) (pH 5.5) and Sulfo-NHS solution in PBS. There was stable chemical conjugation of the microsphere with the surface of the substrate at last. The Poisson’s ratio of the PAAm substrates can be set as 0.5.30

The traction force of cells was calculated from bead displacements between the deformed and undeformed states of the gels. To determine the undeformed state of substrates, the cells were treated with 231 Cell Lysate (Sangon Biotech, China) for cell lysis. Then, bead displacements between the deformed and undeformed state were computed using home-made particle imaging velocimetry (PIV) analysis. The traction forces were measured using Fourier transformed traction microscopy with finite gel thickness.

Image and Statistical Analysis

All images, taken by Leica DMI3000B (Leica, Germany) and confocal microscope (Nikon, Japan), were analyzed with Fiji/ImageJ software.

All data are displayed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of at least three independent samples per experiment. Statistical significance between experimental groups was analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's multiple comparison tests with Origin software. Statistical significance is denoted as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and not significantly different if p ≥ 0.05 (NS). All graphs are drawn by Origin.

Results

Microgrooved PAAm Substrates Fabrication Cell Seeding

Silicon wafers with microgrooved constructions manufactured using traditional lithography, were used as stamps to fabricate PAAm substrates by soft lithography (Fig. 1A). The substrates were stripped from silicon stamps and kept in PBS at 4 °C for use. Then, cells were seeded on microgrooved PAAm substrates (Fig. 1A, D).

To distinguish the influence of the topographical constraints of substrates on MDA-MB-231 cell behaviors, a series of silicon stamps with fixed width of ridges and grooves, varying groove depths; or fixed depth and ridges width, varying grooves width were fabricated. The size of microgrooved silicon stamps was measured using a 3D Optical Profiling system (Fig. 1B, S1A-E, Table S1). And the resulting PAAm substrates with negative surfaces were obtained after polymerization at room temperature (Fig. 1C). Besides, D, R and G represent the depth, ridge width and groove width of the microgrooves, respectively. For example, substrate D5R100G25 referred to the substrate with a design size of 5 μm depth, 100 μm ridge width and 25 μm groove width. Determination of the substrate size showed that the size fluctuates within 10% of the design size. The result suggested that the fabrication of microgrooved PAAm substrates using soft lithography had good pattern fidelity (Table S2). Besides, the Young’s modulus of substrates was determined using AFM. It was found that the stiffness of the grooves and ridges obtained by PAAm polymerization at room temperature is 6.01 ± 0.06 kPa and 6.11 ± 0.08 kPa, respectively (Fig. S2). The constant stiffness aided in improving the accuracy of traction force measurement in different regions.

The Effects of the Dimensions of Substrates on Cell Morphology

To investigate the contact guidance behaviors of MDA-MB-231 cells, the morphological characteristic of MDA-MB-231 cells seeded on the microgrooved substrates was measured by fitting cells as ellipses. Cell alignment angle is defined as the angle between the long axial of cells and the grooves, the angles within ± 10° mean that cells are oriented along the microgrooves.

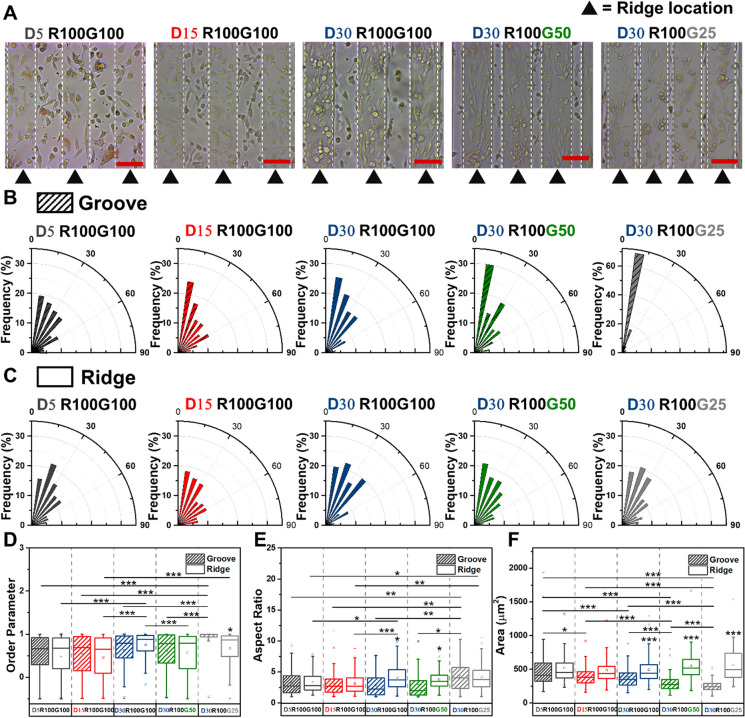

Images obtained at 96 h after seeding showed that cell morphology and orientation were strongly influenced by dimensions of topographic features (Fig. 2A). Directional distribution of cells on microgrooved substrates was depicted in the Fig. 2B. To quantitatively analyze the effects of topology on cell behaviors, the angle distribution, aspect ratio and spreading area of cells on different substrates were determined. As shown in Fig. 2A, cells on the grooves and ridges displayed a similar orientation along the microgrooves. The quantification of cell orientation and orientation parameters revealed that decreasing microgroove width (from 100 to 25 μm) was accompanied with an increase in the fraction of cells (from 22.74 to 48.02%) aligned with grooves (Fig. 2B, D). Determination of the cell aspect ratio and spreading area showed that the elongation of cells in the groove was independent of the groove depth, but increased with the decreasing groove width. Moreover, with the increase of groove depth and decrease of groove width, the spreading area of cells in the groove decreased significantly (Fig. 2E, F). As for the cells on the ridge, their orientation, elongation and spreading were irrelevant to groove depth and width (Fig. 2C–F). Interestingly, when the groove width was reduced to 25 μm, cells in the grooves showed a smaller spreading area but a larger aspect ratio than those of cells on ridges. The maximum difference in aspect ratio and spreading area of cells in the groove and ridge occurred when the depth increased to 30 μm and the groove width decreased to 25 μm. This indicated that the deep and narrow grooves were favourable for cell elongation, but not conducive to the spreading of cells.

Fig. 2.

Quantitative analysis of the morphological features of cells on microgrooved substrates with different dimensions. A The phase contrast microscope images of MDA-MB-231 cells cultured on the microgrooves with different depth (from 5 to 30 μm) and different groove width (from 100 to 25 μm) at 96 h of culture (Scale bars: 100 μm). B-C The orientation angle frequency distribution of cells on grooves and ridges of microgrooves with different depth (from 5 to 30 μm) and different groove width (from 100 to 25 μm), respectively. D–F Comparison of cell order parameters, aspect ratio and spreading area on different substrates. The boxes show the quartiles of the distributions, with the boxes indicating 25th and 75th percentiles, and the whiskers correspond to the maximum and minimum values

The Effects of the Dimensions of Substrates on Cell Spatial Distribution

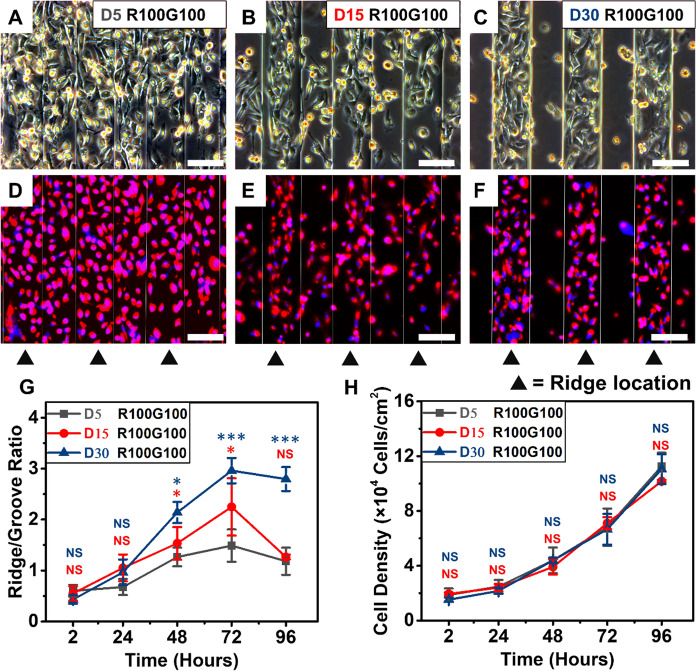

Due to contact guidance, cells can perceive the substrate topographic features, which affects various downstream behaviors of the cells and ultimately guides cell distribution, which is crucial to study embryonic development and cancer invasion.19,34,35 Thus, the spatial distribution of MDA-MB-231 cells on the microgrooved substrate was determined. From phase contrast micrographs and fluorescence images of cells on different substrates (Fig. 3A–F), MDA-MB-231 cells showed a clear preference to gather on the ridges of microgrooves. Besides, this trend became more pronounced with increasing microgroove depth. Quantitative results of the density of MDA-MB-231cells on ridges and grooves of substrates showed that cell spatial distribution changed with culture time (Fig. 3G). R/G is defined as the ratio of cell density at the ridges and grooves of microgrooves, R/G < 1 means that the cell density of the ridges was lower than that of the grooves, while R/G > 1 means the cell density of ridges is higher than grooves.

Fig. 3.

MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured on the microgrooves with same groove and ridge width (100 μm), and different depths of 5, 15 and 30 μm. A–C The phase contrast microscope images of MDA-MB-231 cells cultured on the microgrooves with depth of 5, 15 and 30 μm at 96 h of culture (Scale bars: 100 μm). D–F The fluorescence images of MDA-MB-231 cells stained for F-actin (red) and nuclei (blue) for cells cultured on substrates with depth of 5, 15 and 30 μm, respectively. White scale bars equal 100 μm. G The density of cells growing within the grooves or on the ridges was determined and the Ridge/Groove (R/G) ratio was calculated for different microgroove depth. H The densities of cells located on whole microgrooved substrates with different depths at different culture time

As shown in Fig. 3G, there were no significant differences of R/G ratios among the three groups at 2 h of culture, indicating that the MDA-MB-231 cells on substrates with different depths showed a similar cell distribution after seeding. In all cases, R/G ratios of three groups below 1, which means that the majority of MDA-MB-231 were found to sink to the grooves. Due to the narrow grooves of the substrates, the cells were more likely to land on the grooves rather than the ridges. At the early stage of culture, the R/G ratios increased with culture time and the depth of the microgrooves, from 1.48 ± 0.31 for 5 μm to 2.96 ± 0.25 for 30 μm at 72 h of culture. Then, with rapid cell proliferation, R/G ratios decreased sharply (1.18 ± 0.27, 1.26 ± 0.05 and 2.79 ± 0.23 for depths of 5, 15 and 30 μm) at 96 h of culture. We speculated that the high density of the ridge cells induced the contact inhibition earlier, while the cells at grooves continued to proliferate. The difference in cell preferential spatial distribution on the ridges was weakened and R/G ratios decreased at 96 h of culture (Fig. 3G). Finally, the difference in the ridge-groove distribution of cells on the microgrooved substrates was eliminated with culture time.

To further determine the influence of groove depth on MDA-MB-231 cell behaviors, the cell densities across the entire substrates at different culture times were measured (Fig. 3H). At 72 h of culture, the cell densities were 68,159 ± 13,619, 71,044 ± 4370 and 66,621 ± 11,247 cells/cm2 for substrates with depths of 5, 15 and 30 μm, respectively. Quantification results indicated that there was no significant difference in cell density across entire microgrooved substrates with different depths during culture. Thus, we can conclude that the depth of microgrooves only affects the elongation, spreading and spatial distribution of cells rather than their proliferation.

To distinguish the influence of groove width on the spatial distribution of MDA-MB-231 cells, the substrates with the same depth (30 μm), ridges width (100 μm) and groove width range from 25, 50 to 100 μm were used. MDA-MB-231 cells displayed a preferential spatial localization on ridges of microgroove (Fig. 4A–F). Then, quantification of the R/G ratios revealed that the R/G increased with increasing groove width (Fig. 4G). During 72 h of culture, R/G for groove width of 25 μm increased from 0.29 ± 0.04 to 1.09 ± 0.12, and R/G for groove width of 100 μm increased from 0.33 ± 0.08 to 2.96 ± 0.24. Then, R/G decreased slightly as the cell proliferation slowed down due to contact inhibition. However, there was no significant difference in the density of cells on three types of substrates with different groove widths, which means that the groove width also had little effect on cell proliferation (Fig. 4H).

Fig. 4.

A–C MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured on the microgrooves with same ridges width (100 μm) and depths (30 μm), varying groove width (25, 50 and 100 μm). White scale bars equal 100 μm. D–F The fluorescence images of MDA-MB-231 cells cultured on substrates with groove width of 25, 50 and 100 μm, respectively. White scale bars equal 100 μm. G The density of cell growing within the grooves or on the ridges was determined and the R/G ratio was calculated for microgrooved substrates with different groove width at different culture time. H The densities of cells located on whole microgrooved substrates with different groove widths at different culture time

Observation of Cellular Motility Using Time-Lapse Phase-Contrast Microscopy

To better understand the behavior of MDA-MB-231 cells on the PAAm microgrooved substrates, the cell migration paths were continuously observed using time-lapse phase-contrast microscopy (Fig. 5A–C, Movie S1). The migration behavior of cells can be categorized into RTR, RTGTR, GTR, RTG and GTG. Among them, RTR means cells migrate on the same ridge of microgrooved substrates, RTGTR means cells migrate from ridge to another and across a groove, GTR means cells migrate from groove to adjacent ridge, RTG means cells migrate from ridge to adjacent groove, and GTG means cells migrate on the same groove of microgrooved substrates (Fig. 5A, B). According to the time and displacement obtained from the sequence snapshot, the migration velocities of five motion modes were calculated (Fig. 5C–G).

Fig. 5.

Determination of cell migration trajectories and velocity. A Accumulated cell trajectories after 28.5 h of migration color-coded for the mean migration velocity of cells. B Four types of moving paths of MDA-MB-231 cells cultured on the microgrooved substrates. The velocity of four motion modes: C RTGTR; D RTR; E GTR; F RTG; G GTG, at different times. H–I The average migration velocity and percentage of cells for different motion modes. J Quantification of cell migration velocity on grooves and ridges. K–L Quantification of the trajectory length and migration velocity extracted as the cells climb up the edges from groove to ridges (G- > R) and from ridges to grooves (R- > G), respectively

During observation of 28.5 h, the migration velocities were 0.77 ± 0.10, 0.75 ± 0.11, 0.71 ± 0.15, 0.62 ± 0.13 and 0.59 ± 0.16 μm/min for the motion mode of RTR, RTGTR, GTR, RTG and GTG, respectively (Fig. 5H). The motion mode of RTR had the maximum migration velocity, while the GTG had the minimum migration velocity. Then, the percentage of cells with different migration paths was quantified. The results showed that most of the cells tended to move within the original region. But there were 19.92 ± 4.19% of cells migrated from the groove towards the adjacent ridge, while only 5.54 ± 1.28% of cells migrated to the groove (Fig. 5I). Thus, the density of cells in the ridges was greater than that in the grooves.

Then, the migration speeds of cells on grooves and ridges were quantified and found that the migration speed of cells on ridges was always greater than that of cells on grooves. The result indicated that topological constraints affect the migration activity of cells (Fig. 5J). Then, the trajectories were separated into segments, and the trajectory length and migration velocity of cells on ridges and grooves were quantified (Fig. 5K–L). The results showed that MDA-MB-231 cells had a smaller track length and a higher migration speed during climbing up from grooves to ridges. The statistics of the migration velocity of cells in different regions of the microgroove substrates implied that cells have better movement activity at ridges (Fig. 5J).

Effects of Soluble Factors and Cell-Substrate Adhesion on Cell Spatial Distribution

There are many factors, such as gravity, soluble factors and substrate stiffness, that influence cell motility and further drive cell migration,32,36,37 which is closely associated with various cell behaviors in vivo.2,38 Besides, cell-substrate adhesion is another critical factor for directing the collective migration of cells.34,39 The effects of dissolved soluble factors concentration and cell-substrate adhesion on cell spatial distribution were investigated to determine the reasons for the MDA-MB-231cells motility differences at ridges and grooves.

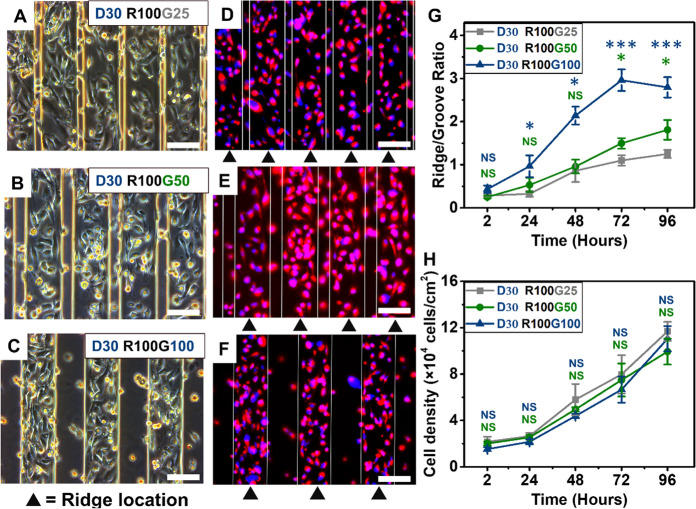

Firstly, the influence of soluble factors on cell spatial distribution was investigated. To eliminate the influence of gravity and liquid layer thickness, the cells were cultured upside down.37 The standard coverslips were placed on each side of the inverted substrates to avoid touching the bottom of the culture dish (Fig. 6A). Then, the grooves of the inverted substrate were close to the liquid surface, while the ridges were close to the bottom of the petri dish. Thus, the soluble concentrations in the grooves and ridges of the inverted substrate were opposite to those of the upright substrate, while the concentration difference remained unchanged. At 12 h of culture, MDA-MB-231 cells adhered to the substrate without obvious spatial distribution difference. Then, the MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured upside down (Fig. 6B). After 5 days of culture, the cells displayed a clear preference to gather at ridges (Fig. 6C). This implied that although the soluble concentrations of ridges and grooves has been reversed, the cells on the inverted substrates still showed a preferential migration toward ridges.

Fig. 6.

A Cells plated upside down on microgrooved substrates to explore the influence of soluble factors on cell distribution. B–C The phase contrast microscope images of cells grown upside down after 12 h and 5 days of seeding, respectively. White scale bars equal 100 μm. D–E The phase contrast microscope images of cells treated with Blebbistatin at 0 h and 48 h of culture, respectively. White scale bars equal 200 μm. F The R/G ratio of cells treated with Blebbistatin at 0 h and 48 h of culture

There are multiple underlying mechanisms of cell migration, among which cell-substrate adhesion displays an important role in various models. Moreover, the formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions is critical for cell-substrate adhesion, thereby affecting the polarization and directional migration of cells. Blebbistatin is a small molecule inhibitor showing high affinity and selectivity toward myosin II.40,41 Thus, Blebbistatin was used to inhibit the formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions by blocking myosin II to determine the role of cell-substrate interaction in cell upward migration. The influence of cell-substrate adhesion on MDA-MB-231 cells upward migration was distinguished by adding Blebbistatin to the culture medium at different culture periods. Due to the inhibitory effect of Blebbistatin on myosin II formation, the cells-substrate adhesion was weakened, which affected cell proliferation and directional migration (Fig. 6D, E). Quantitative results showed that the R/G ratios first decreased and then remained constant at ~ 1 after adding Blebbistatin at 0 h of culture, indicating that the addition of Blebbistatin eliminated the difference of cell distribution between ridges and grooves (Fig. 6F). To further investigate the effects of cell-substrate adhesion on cell migration and spatial distribution, the Blebbistatin was added to the medium at 48 h of culture after cells showed significant differences in spatial distribution. As shown in Fig. 6F, during the culture of 48 to 96 h, the R/G ratio of the group added with Blebbistatin at 48 h decreased rapidly from 1.75 ± 0.38 to 0.66 ± 0.18. The final R/G ratio was almost the same as that of the group adding Blebbistatin at 0 h. This revealed that the preferential spatial localization of cells aggregated on the ridges was eliminated as the cell directional migration was inhibited.

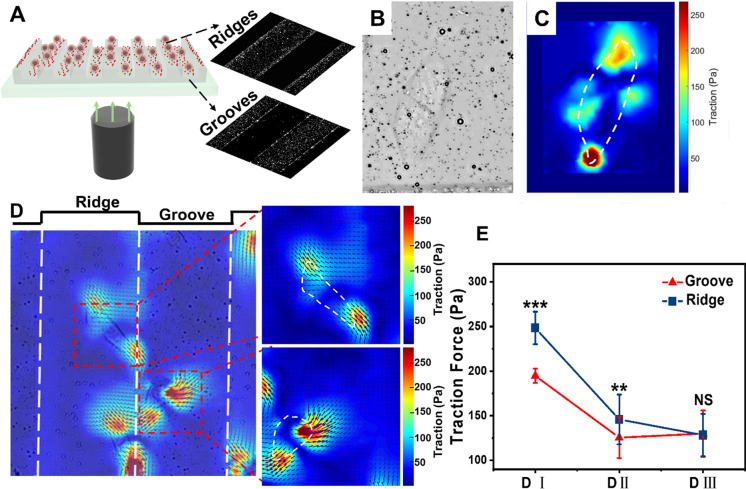

To quantitatively assess the cell-substrate adhesion of MDA-MB-231 cells located on ridges and grooves, the TFM was used to determine the traction force of cells. The TFM ensured the efficient characterization of the traction force of cells on topographical patterns with a certain height (Fig. 7A, Movie S2). Since the spatial distribution of cells was more sensitive to the depth, substrates with the same groove and ridge widths (100 μm) and different depths were used to investigate the influence of topographic features dimensions on cell behaviors (Fig. 7B, C). The traction force direction (arrows) and magnitude (length of arrows) of cells were calculated from bead displacements between the deformed and undeformed state of the PAAm substrates (Movie S2). For cells located on grooves, most traction forces were directed towards the adjacent ridges, which was consistent with the phenomenon that cells tended to migrate from grooves to ridges (Fig. 7D). In addition, the force field of cells on ridges of substrates directed towards the ridge center, indicating that cells tended to migrate from ridge edge to ridge center (Fig. 7D). Quantitative analysis of traction force showed that traction force of MDA-MB-231 cells decreased with groove depth from 194.68 ± 8.01 to 129.97 ± 26.01 for grooves, 248.33 ± 18.22 to 128.28 ± 23.77 for ridges (Fig. 7E). Moreover, cell traction forces on the ridges were always larger than that on the grooves (Fig. 7E). The large traction force always offers greater potential for cells migration, which results in greater cell motility in the ridges.

Fig. 7.

Traction force distributions of MDA-MB-231 cells on substrate groove and ridge. A TFM is obtained by combining confocal microscopy with TFM, which enables in situ determination of traction force of cells on ridges and grooves. B Phase contrast image of MDA-MB-231 cell on the substrate. C The magnitude and distribution of traction forces of corresponding cell was detected using TFM. White dotted outlines define cell boundaries. D Composite diagram of traction and force field of cells on substrate groove and ridge. Zoomed region is indicated by the red box and is shown to the right. E Maximum traction of MDA-MB-231 cells cultured on substrates of different depth

Discussion

Microgrooved substrates with depths and widths at mesoscopic scale were prepared to investigate the cell contact guidance behaviors. The comprehensive analysis of cell orientation, aspect ratio and spreading area, implied that the spatial confinement imposed by microgrooves induced an optimum alignment along grooves due to contact guidance. Besides, the morphological characteristics of cells implied that cell behaviors were closely related to the topographic features size of the substrates. We speculated that decreasing groove width provided lateral confinement of cells, which restricted the orthogonal spreading of cells, and resulted in more aligned and elongated morphology along grooves. The spatial confinement diminished cell spreading and resulted in a smaller spreading area. Whereas, the spatial confinement of grooves cannot affect the cells on the ridge, the morphology of the cells on the ridge was almost independent of groove sizes. Moreover, MDA-MB-231 cells displayed a preferential distribution of aggregation at the ridges. The tracking of cell migration implied that the different spatial confinement of grooves and ridges led to different cellular motility, thereby promoting cell migration from grooves to ridges. This phenomenon revealed that the preferential spatial distribution to the ridge of MDA-MB-231 cells was caused by the difference in cell motility.

By culturing cells upside down, we found that the height difference between ridges and the grooves was not large enough to produce sufficient soluble factor concentration difference, which was consistent with previous studies.36 Thus, cells cannot be driven to migrate from a low soluble factor concentration region (the ridge of inverted substrates) to a high soluble factor concentration region (groove of inverted substrates). This finding implies that the soluble factor concentration is not the crucial factor that drives the upward migration of MDA-MB-231 cells on microgrooved substrates. Besides, by blocking cell-substrate interaction using Blebbistatin, the preferential spatial localization of cells aggregated on the ridges was eliminated. The result revealed the important role of cell-substrate interaction in the upward migration of MDA-MB-231 cells. We speculated that the polarization of migrating cells was weakened by blocking the cell-substrate adhesion using Blebbistatin. And cells migrated randomly, rather than gathered in a certain area of the substrate. Thus, we concluded that MDA-MB-231 cell upward migration was irrelevant to soluble factors concentration but closely related to cell-substrate adhesion.

The determination of the traction force field also confirmed the hypothesis that cell upward migration was dominated by cell-substrate adhesion due to contact guidance. Based on the comparison of the magnitude and direction of the traction force of cells at different regions of the substrate, we concluded that cell migration was dominated by the direction of the traction force rather than the size of the traction force, which was consistent with the results of previous study.23 The above results suggested that differences in topological spatial confinement of grooves and ridges led to differences of cell-substrate interactions, which resulted in different cell activity and drove cells to migrate toward ridges. Compared with the cells on the grooves, the cells on the ridges had less concentrated alignment and larger spreading area, which referred to larger morphological entropy (Fig. 2B, C). Thus, cells upward migration emerged from the driving force of cells to maximize morphological entropy and their overall state of disorder (Fig. 8). The increasing depth induced a more ordered orientation of cells on grooves and drove cells to migrate upward, which resulted in more dominant preferential spatial localization on ridges. This implied that cells had a contact guidance mechanism based on entropic force driven theory to respond to the topological structure with dimensions at the mesoscopic scale.

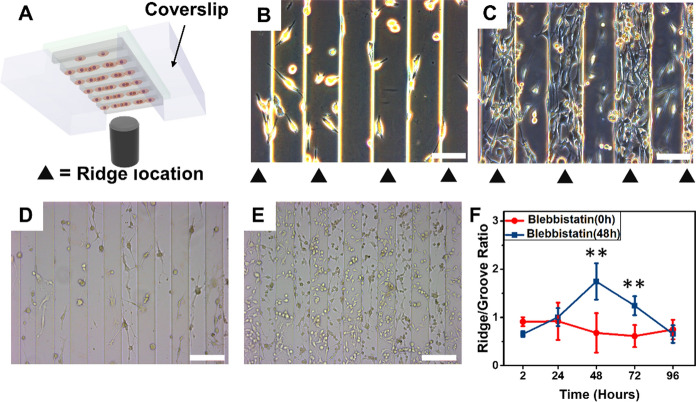

Fig. 8.

Mechanism of cell upward migration at substrates with topographic features at mesoscopic scale. Cells migration from the grooves to ridges to maximize their morphological entropy and and led to the aggregation of cells in the ridge

Conclusion

This study is significant because it aims to systematically study the contact guidance response of MDA-MB-231 cells to mesoscopic topological features. Due to the contact guidance, cells responded to topographic features and exhibited depth-dependent and width-dependent elongation, spreading and alignment. Moreover, the behavior of the cell was closely related to its location, showing limited elongation and spreading at grooves due to lateral confinements. In addition, MDA-MB-231 cells showed a preferential distribution on the ridges in response to topographic features dimensions, which became more pronounced with increasing groove width and depth. The tracking of cell motion path and velocity using time-lapse phase-contrast microscopy reflected the fact that the preferential distribution was caused by different cell motility.

To determine the underlying mechanism of upward migration, the effects of dissolved soluble factors concentration and cell-substrate adhesion on cell migration were investigated. The results showed that the cell-substrate adhesion, rather than soluble factors concentration was the main reason for the preferential distribution of cells. Then, the determination of cells' traction force revealed that cells' upward migration was closely related to anisotropic traction generated by cell-substrate adhesion due to contact guidance. Based on the investigation of spatial distribution and migration of cells on microgrooved substrates, we found that the upward migration relied on the mechanism based on entropic force driven theory. We hypothesized that the cells are subjected to spatial confinement on substrates with groove width at the mesoscopic scale, which promoted the upward migration of cells to maximize morphological entropy. Overall, our hypothesis provides a theoretical framework for studying the contact guidance response of cells, which can serve as a basis for further research in cancer metastasis and anticancer treatments.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors also thank Ze Cai from Key Laboratory of Precision Scientific Instrumentation of Anhui Higher Education Institutes, University of Science and Technology of China; Ran Rao from CAS Key Laboratory of Mechanical Behavior and Design of Materials, Department of Modern Mechanics, University of Science and Technology of China, for their help with AFM measurement and observation of cellular motility using time-lapse phase-contrast microscopy.

Author Contributions

XC, YX, WD, and JC contributed to the conception and design of the study. HL, RH, and YS performed the experiments and analyzed the data. WX and YM contributed to writing reviews and editing. XC contributed to the original draft writing. JC contributed to funding acquisition and review. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version. All authors reviewed this manuscript, contributed, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 51905248].

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Xiaoxiao Chen, Youjun Xia, Wenqiang Du, Han Liu, Ran Hou, Yiyu Song, Wenhu Xu, Yuxin Mao and Jianfeng Chen declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

No human or animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiaoxiao Chen and Youjun Xia are co-first authors

References

- 1.Zhao YF, et al. Modulating three-dimensional microenvironment with hyaluronan of different molecular weights alters breast cancer cell invasion behavior. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:9327–9338. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b15187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Labat B, et al. Biomimetic matrix for the study of neuroblastoma cells: a promising combination of stiffness and retinoic acid. Acta Biomater. 2021;135:383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhovmer AS, et al. Mechanical counterbalance of kinesin and dynein motors in a microtubular network regulates cell mechanics, 3D architecture, and mechanosensing. ACS Nano. 2021;9:4891. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c04435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reversat A, et al. Cellular locomotion using environmental topography. Nature. 2020;582:582–585. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2283-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Putten C, et al. Protein micropatterning in 2.5D: an approach to investigate cellular responses in multi-cue environments. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021;13:25589–25598. doi: 10.1021/acsami.1c01984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ray A, et al. Anisotropic forces from spatially constrained focal adhesions mediate contact guidance directed cell migration. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14923. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwang Yu-Shik, et al. Microwell-mediated control of embryoid body size regulates embryonic stem cell fate via differential expression of WNT5a and WNT11. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:16978–16983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905550106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasputis T, et al. Use of precisely sculptured thin film (STF) substrates with generalized ellipsometry to determine spatial distribution of adsorbed fibronectin to nanostructured columnar topographies and effect on cell adhesion. Acta Biomater. 2015;18:88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hui J, Pang SW. Cell traction force in a confined microenvironment with double-sided micropost arrays. RSC Adv. 2019;9:8575–8584. doi: 10.1039/C8RA10170A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yao X, Ding J. Effects of microstripe geometry on guided cell migration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12:27971–27983. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c05024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim DH, et al. Nanoscale cues regulate the structure and function of macroscopic cardiac tissue constructs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:565–570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906504107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J, Schneider IC. Myosin phosphorylation on stress fibers predicts contact guidance behavior across diverse breast cancer cells. Biomaterials. 2017;120:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Driscoll MK, et al. Cellular contact guidance through dynamic sensing of nanotopography. ACS Nano. 2014;8:3546–3555. doi: 10.1021/nn406637c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lugassy C, et al. Angiotropism, pericytic mimicry and extravascular migratory metastasis: an embryogenesis-derived program of tumor spread. Angiogenesis. 2020;23:27–41. doi: 10.1007/s10456-019-09695-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paul CD, et al. Cancer cell motility: lessons from migration in confined spaces. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2017;17:131–140. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bentolila LA, et al. Imaging of angiotropism/vascular co-option in a murine model of brain melanoma: implications for melanoma progression along extravascular pathways. Sci. Rep. 2016 doi: 10.1038/srep23834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nouri-Goushki M, et al. 3D-printed submicron patterns reveal the interrelation between cell adhesion, cell mechanics, and osteogenesis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021;13:33767–33781. doi: 10.1021/acsami.1c03687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins SG, et al. High-aspect-ratio nanostructured surfaces as biological metamaterials. Adv. Mater. 2020;32:e1903862. doi: 10.1002/adma.201903862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Saux G, et al. Cell-cell adhesion-driven contact guidance and its effect on human mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12:22399–22409. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b20939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buskermolen ABC, et al. Entropic forces drive cellular contact guidance. Biophys. J. 2019;116:1994–2008. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buskermolen ABC, et al. Cellular contact guidance emerges from gap avoidance. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2020;1:100055. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrp.2020.100055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Z, et al. Cellular traction forces: a useful parameter in cancer research. Nanoscale. 2017;9:19039–19044. doi: 10.1039/C7NR06284B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koch TM, et al. 3D traction forces in cancer cell invasion. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e33476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polacheck WJ, Chen CS. Measuring cell-generated forces: a guide to the available tools. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:415–423. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinwachs J, et al. Three-dimensional force microscopy of cells in biopolymer networks. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:171–176. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sunyer R, et al. Collective cell durotaxis emerges from long-range intercellular force transmission. Scienece. 2016;353:1157–1161. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Style RW, et al. Traction force microscopy in physics and biology. Soft Matter. 2014;10:4047–4055. doi: 10.1039/c4sm00264d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vedula SRK, et al. Emerging modes of collective cell migration induced by geometrical constraints. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:12974–12979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119313109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang X, et al. A novel cell traction force microscopy to study multi-cellular system. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franck C, et al. Three-dimensional traction force microscopy: a new tool for quantifying cell-matrix interactions. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dembo M, Wang Y-L. Stresses at the cell-to-substrate interface during locomotion of fibroblasts. Biophys. J. 1999;76:2307–2316. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77386-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leclerc A, et al. Three dimensional spatial separation of cells in response to microtopography. Biomaterials. 2013;34:8097–8104. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Onochie OE, et al. Epithelial cells exert differential traction stress in response to substrate stiffness. Exp. Eye Res. 2019;181:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2019.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang H, et al. Anisotropic stiffness gradient-regulated mechanical guidance drives directional migration of cancer cells. Acta Biomater. 2020;106:181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedl P, Gilmour D. Collective cell migration in morphogenesis, regeneration and cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:445–457. doi: 10.1038/nrm2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su WT, et al. Observation of fibroblast motility on a micro-grooved hydrophobic elastomer substrate with different geometric characteristics. Micron. 2007;38:278–285. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bailey-Hytholt CM, et al. Enrichment of placental trophoblast cells from clinical cervical samples using differences in surface adhesion on an inclined plane. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2021;49:2214–2227. doi: 10.1007/s10439-021-02742-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Unnikandam Veettil SR, et al. Cancer cell migration in collagen-hyaluronan composite extracellular matrices. Acta Biomater. 2021;130:183–198. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miroshnikova YA, et al. Adhesion forces and cortical tension couple cell proliferation and differentiation to drive epidermal stratification. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018;20:69–80. doi: 10.1038/s41556-017-0005-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Z, et al. Blebbistatin inhibits contraction and accelerates migration in mouse hepatic stellate cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010;159:304–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00477.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kovacs M, et al. Mechanism of blebbistatin inhibition of myosin II. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:35557–35563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.