Abstract

Objectives

This scoping review seeks to detail experiences of inequitable treatment, as self-reported by international medical graduates (IMGs), across time and location.

Design

Scoping review.

Search strategy

Three academic medical databases (MEDLINE, SCOPUS and PSYCINFO) and grey literature (GOOGLE SCHOLAR) were systematically searched for studies reporting first-hand IMG experiences of perceived inequitable treatment in the workplace: discrimination, prejudice or bias. Original (in English) qualitative, quantitative, mixed studies or inquiry-based reports from inception until 31 December 2022, which documented direct involvement of IMGs in the data were eligible for inclusion in the review. Systematic reviews, scoping reviews, letters, editorials, news items and commentaries were excluded. Study characteristics and common themes were identified and analysed through an iterative process.

Results

We found 33 publications representing 31 studies from USA, Australia, UK, Canada, Germany, Finland, South Africa, Austria, Ireland and Saudi Arabia, published between 1982 and 2022. Common themes identified by extraction were: (1) inadequate professional recognition, including unmatched assigned work or pay; (2) perceived lack of choice and opportunities such as limited freedoms and perceived control over own future; (3) marginalisation—subtle interpersonal exclusions, stereotypes and stigma; (4) favouring of local graduates; (5) verbal insults, culturally or racially insensitive or offensive comments; and (6) harsher sanctions. Other themes identified were effects on well-being and proposed solutions to inequity.

Conclusions

This study found evidence that IMGs believe they are subject to numerous common inequitable workplace experiences and that these experiences have self-reported repercussions on well-being and career trajectory. Further research is needed to substantiate correlations and causality in relation to outcomes of well-being and differential career attainment. Furthermore, research into support for IMGs and the creation of more equitable workforce environments is also recommended.

Keywords: mental health, education & training (see medical education & training), stereotyping, health services administration & management, international health services, interprofessional relations

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This scoping review is the first to focus on international medical graduate-reported inequitable experiences and associated outcomes.

We were guided by the Arksey and O’Malley scoping review framework and PRISMA-ScR checklist to ensure methodology was systematically and thoroughly undertaken.

Broad key terms and relevant explosions were used in academic database searches, thereby generating a wide range of publications for review, across time and place.

Methodical handling of the evidence across a variety of databases allowed simple identification of common themes and gaps for further study.

The primary limitation of the study is the exclusion of editorials, news articles, perspectives, non-English publications and merged data, thereby missing potentially important voices and experiences outside those presented in this article.

Introduction

Many developed nations rely heavily on international medical graduates (IMGs) to provide essential population-wide medical services. Since 2015, UK has seen increasing numbers of IMGs, such that approximately 1:3 doctors are foreign trained. This is similar to numbers seen in Australia (1:3) and USA (1:4).1–3

In 2019, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development reported increased numbers of both local and foreign trained doctors across member countries, indicating a general increase in demand to manage current and projected doctor shortages.4 IMGs are needed to fill workforce shortages, attributed to a number of factors, such as population growth and ageing, medical migration to countries with better working conditions and clinician loss to non-clinical industries.5 6 Internationalisation of medical student education also contributes to IMG figures. For example, in USA, Israel, Norway and Sweden a sizeable number of IMGs are comprised of their own citizens who have returned after being educated as international medical students overseas.4 High numbers of international medical students, such as in Ireland, result in a paradoxical situation where graduated students return to their home country, thereby leaving the host country dependant on IMGs to fill doctor shortages.7 To sustain workforces, governments must understand and support the needs and experiences of their workers.5 There are several international studies exploring IMGs’ challenges and acculturation in host countries. Motala and Van Wyk’s 2019 scoping review identified common IMG experiences such as problems related to professional boundaries, lack of country-specific knowledge and personal stressors.8 Motala also identified issues related to workplace discrimination, career limitation and bias, cited in a small handful of studies from Germany, Australia and USA.8 Similarly, Al Haddad et al’s 2021 qualitative meta-ethnography of IMG experiences observed general reports of racism, marginalisation and discrimination impacting career progress.9

Although Motala and Al-Haddad both identified reports of perceived discrimination, bias and prejudice as a common subfinding in IMG research, there have been very few instances of original research published which directly address these concepts. Moreover, there is no unifying document addressing the types of the inequitable experiences described in IMG-related studies.

Exploring concepts of perceived inequitable treatment is important. Not only as a moral obligation to our colleagues, but because discrimination may influence career direction, physical health and well-being.10–12 Therefore, this scoping review aims to explore experiences of workplace-related discrimination, prejudice and bias as reported by IMGs worldwide. This topic is broad, yet complex and heterogenous, thereby lending itself to scoping review.13 Furthermore, as relevant studies are disseminated across location and time, a scoping review approach allows appreciation of the evidence range and identification of knowledge gaps.

Research question and objective

The research question was defined as: ‘What common experiences of inequitable treatment have been examined and reported by IMGs in the literature?’ For this study, IMG was defined as a medical doctor who obtained their primary medical qualification from a country external to the country, they currently work in. Inequitable treatment was defined as self-reports of discrimination, bias or prejudice by IMGs. The objective was to summarise the number and types of studies reporting experiences of workplace discrimination perceived by IMGs worldwide and identify common themes of inequitable treatment.

Methods

The five-step Arksey and O’Malley framework was used to guide the review process.13 The steps included: identifying the research question, identifying and selecting relevant studies, extracting data and finally, collating and reporting the data. The PRISMA-ScR checklist was used as a guide for reporting.14

Information sources and search: studies published in MEDLINE, PSYCINFO and SCOPUS databases, in addition to GOOGLE SCHOLAR were systematically searched (see online supplemental appendix 1). Using appropriate Boolean operators, an initial pilot search through MEDLINE was conducted using MesH and keywords related to: ‘international medical graduate’, ‘foreign medical graduate’, ‘foreign doctor’ and ‘overseas trained doctor’ in combination with terms: ‘discrimination’, ‘racism’, ‘prejudice’ and ‘bias’. Following the pilot, additional terms: ‘challenges’ and ‘negative experiences’ were included to broaden the search. After completing a final version of the search through MEDLINE, the search was replicated for two other scientific databases (PSYCINFO and SCOPUS) for peer-reviewed publications, from inception to 31 December 2022. To review the grey literature, GOOGLE SCHOLAR was searched using similar search terms as the scientific databases. For efficiency, we limited the GOOGLE SCHOLAR search to consider the first 50 (of 2660) publications, as presented by relevance. Finally, hand searching through relevant references and associated publications were added to the grey literature search.

-

Selection of sources of evidence: as the researchers are native English speakers, only publications reported in English or with English versions were included in the review. To ensure that IMG voices were directly heard, and raw experiences were presented without external interpretation, only publications documenting direct involvement of IMGs in the study data were included.

Original qualitative, quantitative, mixed studies or inquiry-based reports were eligible for inclusion in the review. Systematic reviews and scoping reviews were excluded from the study, to reduce duplication and maintain focus on primary results. Letters, editorials, news items and commentaries were also excluded, to reduce duplication and avoid confusion about the author’s origin. Reports which amalgamated data between IMGs and other groups (eg, black and ethnic minority) were only included if IMG-specific data were explicitly reported and clearly extractable in the Results section. The researchers were mindful to delineate reports of discrimination, bias or prejudice vs reports related to general hardships of migration or adjustment difficulties due to transition as a foreigner to a new land and workplace. Therefore, only studies which explicitly described perceptions of discrimination, prejudice or bias or related terms such as stigma or stereotype were included. General results related to foreign policy, immigration and language were not included.

-

Data extraction process: the primary reviewer (SJRH) undertook 2 × 2 hour workshops about scoping studies and was supported by a second reviewer (KF) with expertise in the study methodology. Search items were imported into ENDNOTE and then COVIDENCE—a screening and data extraction tool used to assist reviewers with conducting academic reviews. Duplicates were removed by the COVIDENCE tool prior to screening. Two reviewers (SJRH and KF) created a calibrated form documenting inclusion and exclusion criteria. The reviewers evaluated and modified the variables after first piloting the first 20 (of 544) publications together. This ensured that included studies addressed the research question, aim and objectives. Remaining publications were assessed by both reviewers independently, screening titles and abstracts for inclusion according to the calibrated form. Reviewers discussed any mismatches which were identified by the COVIDENCE tool. The screening process was repeated for full-text screening. A third overseeing reviewer with expert content knowledge (BRN) was assigned to provide final verdict for any disagreements, but consultation was not required.

Through an iterative process, the reviewers (SJRH and KF) met regularly to create, test, refine and finalise an extraction table based on common themes identified by the reports. About 20% of the reports were thoroughly extracted against the refined extraction table by both reviewers and the remainder were extracted independently by the primary reviewer (SJRH). Any uncertainties were flagged and discussed at regular intervals between the reviewers. Both reviewers discussed and agreed on items for inclusion, appraisal of reports and synthesis of results.

-

Data items: standard items were chosen for extraction—author/citation, year and country of publication, type of publication and study, methodology including participant numbers and study objectives/aims/purpose. The reviewers identified common themes, which were iteratively grouped into six major data items and a seventh item reporting general comments (see below). Further iteration supported extraction of two more items—impacts on well-being and proposed solutions to inequity. Relevant results and quotations were charted into an Excel spreadsheet and transferred to a Word document table for manual synthesis.

Methods were assigned to one of three categories: qualitative/interview, survey/questionnaire or mixed. Each publication was assessed if the purpose, aim or objective and methodology referred to exploration of inequitable treatment (including discrimination, bias or prejudice), well-being (including satisfaction and mental health), both or neither. The common themes arising as data items were: (1) inadequate professional recognition; (2) perceived lack of choice and opportunities; (3) marginalisation; (4) favouring of local graduates; (5) verbal insults; and (6) harsher sanctions.

bmjopen-2023-071992supp001.pdf (60KB, pdf)

Synthesis of results

We synthesised the results according to five domains: (1) year and country of publication; (2) methodology; (3) dominant themes of perceived inequitable treatment; (4) reported impacts on well-being; and (5) proposed solutions to IMG inequity experiences.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involvement.

Results

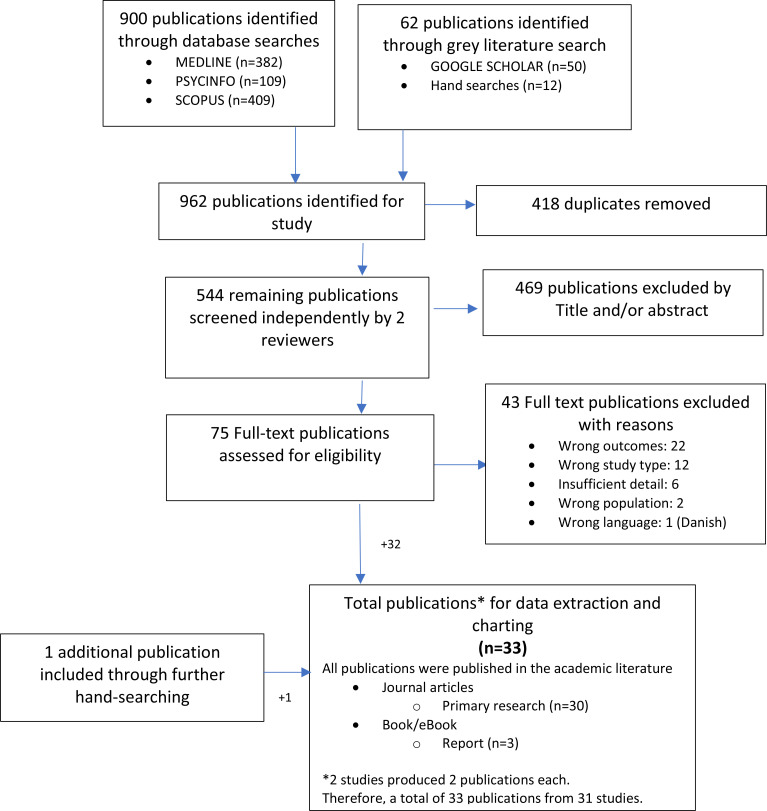

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram of literature search. A total of 900 publications were identified through the database searches: MEDLINE (n=382), PSYCINFO (n=109) and SCOPUS (n=409); in addition to the grey literature search GOOGLE SCHOLAR (limited to the first 50 publications) and handsearching (n=12 publications); totalling 962 publications identified for scoping review. Following the removal of duplicates (n=418), 544 publications were screened by title and author by two reviewers independently. A resulting 75 publications were assessed by both authors independently for eligibility before 43 publications were excluded with reasons. For example, three potentially relevant studies were excluded based on insufficient detail, as IMGs’ scrutiny was not clearly attributed to discrimination, bias or prejudice.15–17 At this stage, an additional publication (295-page book) was identified on handsearching.18 Full-text publications were excluded based on wrong outcomes, wrong study type, insufficient detail or wrong population; one Danish publication19 was excluded as no English translation was available to the authors. Where publications had multiple exclusion reasons, the higher-ranked reason on the calibration form was assigned. Three publications presenting amalgamated data were included but extracted only against the explicit IMG voice mentioned within the publications.10 20 21 Two studies presented two publications each.22–25 Therefore, a total of 33 publications, representing 31 studies, progressed to data extraction.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of literature search.

Characteristics of sources of evidence

The 33 publications included 3 book/eBook reports1 18 26 and the remaining 30 represented primary academic research publications. Two publications1 10 used various methods including focus groups and written submissions in addition to individual IMG interviews to report findings. One study used two qualitative techniques- focus group interview in addition to a 10-min ‘critical incident’ narrative writing.27 Overall, the majority (21/33) of publications were based on qualitative/interview methods alone, 7/33 used questionnaire/survey alone and 5/33 used mixed methods (see online supplemental appendix 2).

bmjopen-2023-071992supp002.pdf (151.6KB, pdf)

We tabulated extraction results by year, to help identify any patterns of recorded inequitable treatment over time. We extracted four publications published prior to year 2000, the earliest being a British national report from 1982.18 There has been a steady production of relevant publications over the past 20 years up until 2022. Almost half of the publications originated from USA and Australia combined, as seen in table 1.

Table 1.

Number of publications extracted by country

| Country of publication | Number of relevant reports | Year(s) of report |

| USA | 8* | 1997, 1998, 2005, 2006, 2010*, 2011*, 2013, 2022 |

| Australia | 7 | 2004, 2005, 2005, 2008, 2009, 2012, 2021 |

| UK | 6 | 1982, 2002, 2015, 2016, 2021, 2021 |

| Canada | 4 | 1983, 2004, 2015, 2019 |

| Germany | 2 | 2016, 2022 |

| South Africa | 1 | 2021 |

| Finland | 2† | 2018†, 2019† |

| Austria | 1 | 2015 |

| Ireland | 1 | 2013 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | 2020 |

| Total | 33 |

*Seven studies, eight publications.

†One study, two publications.

On reviewing the aims, objectives and methods of each study report, the majority did not directly seek data related to inequitable treatment or well-being. Inequitable treatment data alone was sought in 6/31 studies20 21 28–31; well-being data were sought in 2/31 studies26 32 and 3 studies sought both items.10 21 22 33

Common themes of inequitable treatment

We found several recurrent themes across time and country. The majority (24/33) of publications documented ≥2 common IMG experiences related to inequitable treatment. Common experiences did not appear to follow any particular pattern over time. Common themes identified were: (1) inadequate professional recognition, including unmatched assigned work or pay; (2) perceived lack of choice and opportunities such as limited freedoms and perceived control over own future; (3) marginalisation—subtle interpersonal exclusions, stereotypes and stigma; (4) favouring of local graduates; (5) verbal insults, culturally or racially insensitive or offensive comments; (6) harsher sanctions; and (7) general comments about discrimination which were not otherwise specified.

Inadequate professional recognition was reported in 70% (23/33) of publications and was reported as occurring on either an interpersonal level or institutional level. This included experiences such as skill sets being under recognised or inferiorly matched to assigned work1 10 18 26 29 30 33–38 and pay or benefits not matched to experience level.10 20 26 39 Non-individualised bureaucratic responses to recognition into prior experience and qualifications were criticised in studies from UK,18 USA22 and Canada30 and Australia,26 38 40 including a federal Australian parliamentary report.1 Other studies described a lack of recognition from colleagues, a perceived inferiority and lack of value of the IMG qualification.28 34 41–43 Hawthorne’s 2004 Australian report26 found IMGs reporting ‘exploitation’ of hours worked for payment received, dissatisfaction with practice costs and long-term earning opportunities in addition to differing Medicare rebates based on location and registration conditions. Coombs’ 2005 USA study20 found that 28% of IMG survey respondents reported that they had experienced ‘my pay and/or benefits were not equivalent to my peers at my level’, while only 4.8% white, non-IMGs agreed with the statement. Zawawi’s 2020 Saudi qualitative study39 described IMG reports of salary scales based on nationality. Another common report within this category was the notion of needing to ‘work double as hard’ when competing against local graduate colleagues22 28 31 35 37 39 44 for acquiring career promotion and awards.

Perceived lack of choice was reported in 58% (19/33) of publications. IMGs reported that restrictions imposed by institutions contributed to clustering of IMGs in relatively unpopular or peripheral geographical locations and specialties.18 22 35 Disproportionate allocations of IMGs to non-training or peripheral locations were reported as contributing to unfair workloads and restricted study preparation opportunities experienced by IMGs.1 18 22 26 33 35 Terms such as ‘forced’,33 ‘exploitation’,26 ‘(no) liberty’,23 ‘no choice’,1 34 ‘trapped’,35 ‘inability’,36 ‘ineligible’31 and ‘systemic inequality’21 were used by IMGs describing their career and workplace options.

Marginalisation was reported in 52% (17/33) of publications. Marginalisation included subtle interpersonal exclusion,1 18 22 23 27 28 37 41 isolation,1 23 45 othering,10 23 26 30 32 42 45 46 stigma10 26 42 and stereotypes.30 41 44 These interpersonal experiences were reported as occurring between IMGs and their local graduate medical colleagues, senior colleagues and other staff such as nurses. Experiences were described as ‘slighting attitudes’,26 ‘insensitivity and isolation’,23 ‘rejection’,18 37 ‘sense of exclusion’,28 ‘hostility’18 30 32 and ‘unwelcoming’.23 27 39 The publication by Hall reported: ‘I didn’t feel that I am different-except when people treat me different’.45 ‘Disfigurement of non-anglicised names’ was described as a microaggression by both British national reports from 198218 and 202110 and suggested to be secondary to the ‘acquiescence of the inferiority of position in the healthcare system of [foreign] doctors.’10

Favouring of local graduates by institutions and individuals was reported in 30% (10/33) of publications. IMGs reported disadvantage because local graduates were routinely preferred and appointed for positions. Sometimes this occurred despite IMGs having superior experience.18 29 33 39 Some reports attributed this to an informal ‘old boys club’, favouring local graduates known to senior consultants.1 18 44 Some reports identified a differential preference within IMG groups also, such that European IMGs or those from Commonwealth countries would have preferential selection over non-white IMGs.18 30 33

Verbal insults, such as culturally inappropriate or derogatory remarks were reported by IMGs relatively less commonly, at 33% (11/33) of publications. Offensive remarks were reported as originating from patients: for example, ‘I don’t want to see that yellow doctor’47 and staff: for example, ‘if you cut this, I will send you back to Saudi…’.45

Harsher punitive sanctions experienced or anticipated by IMGs were noted in 9% (3/33) publications, in relation to registration, English testing,26 repercussions for speaking out1 and formal investigations into professional standards.10

General comments: 36% (12/33) of publications made general comments of IMG discrimination, bias or prejudice. Three of these publications24 25 48 were coded solely within this category as no further details about inequity experiences were provided. ‘General comments’ also included extra information from extracted publications which were not noted elsewhere.

Numerous publications mentioned career deviation, stagnation and/or loss of skills resulting from the categories: ‘inadequate professional development’,1 10 26 30 33–36 38 ‘perceived lack of choice and opportunities’1 10 18 23 26 31 33–36 38 39 44 and ‘favouring of local graduates’.1 10 18 31 34 39 44

Reports on well-being

We found that 55% (18/33) publications mentioned effects on well-being (including satisfaction and mental health) within their Results sections. Sometimes this related to the acculturation process of migrating and living in a foreign land.10 24–26 31–33 46 49 However, the vast majority were associated with reports of inequitable treatment and were seen from the earliest extracted report in 1982,18 up until 2022.32 Of the 10 studies which used surveys, only one explicitly reported using a psychometrically validated instrument.24 25

Table 2 shows the number of publications identifying common themes and the fraction/percentage of such publications identifying detrimental effects on well-being. Of the publications extracted, none identified ‘favouring of local graduates’ for detrimental well-being.

Table 2.

Detrimental effects on well-being as identified through scoping review common themes

| Common theme | Inadequate professional recognition | Perceived lack of choice/opportunities | Marginalisation | Favouring of local graduates | Verbal insults | Harsher sanctions |

| Number of reviewed reports which express theme (out of 33) | 23 | 19 | 17 | 10 | 11 | 3 |

| Number, percentage and citations of themed reports expressing detrimental effects on well-being | 6/23 (26%)1 24 26 33 35 36 |

6/19 (31.5%)18 22 23 26 33 35 |

5/17 (29.4%)10 27 31 32 45 |

0/10 (0%) |

1/11 (9%)47 |

2/3 (66.7%)1 27 |

| Reported detrimental effects on well-being, satisfaction or mental health | Degrading, feeling like ‘second class citizen’, poor self-esteem/confidence, undervalued, pressure, stress | Trapped, demoralised, disempowered, loss of autonomy, hopeless, captive | Feeling unwelcome, struggle for acceptance, unsupported, confidence lowering, burnout, social isolation, fear | – | Deterrent to integration; negative comments produce lasting and profound (psychological) impacts | Fear of repercussions, anxiety |

Proposed solutions to inequity

Seventy per cent (23/33) publications presented potential solutions to experiences of IMG inequity. Solutions were grouped into four: (1) experience sharing; (2) workplace assistance; (3) structural review and change; and (4) workplace harmony. See box 1 for details.

Box 1. Proposed solutions to IMG inequity.

Experience sharing

IMG mentoring.10 23 40–43

Networking.23 25 32

Workplace assistance

Dedicated services to support and supervise IMGs.20 21 32 40 42 46

Social initiatives to support integration.26

Registration, training and examination support.26 37 42 43

Renumeration to off-set disadvantages of decentralised postings.26

Structural review and change

Institutional investigation into structural inequities.10 18 22 23

Transparency and fairness in recruitment and open expectations provided to prospective recruits.18 35 37 39

Equitable and relevant job/training placements.1 18

Review and transparency of processes recognising prior experience and qualifications.1 40

Removal of structural barriers and promotion of pathways for skill-use, achievement and career attainment.1 10 24 25 31 44

Modification of rotation systems to assist stability.35

Workplace harmony

Raising awareness through diversity training and antidiscrimination training.20–25 30 31 37 41

Fostering workplace inclusion, celebrating diversity, migrant contributions and leadership.10 21 23 25 30 37 39

Critical appraisal within source of evidence

Four publications did not directly report the number of IMGs in the study.10 21 34 48 One study did not identify an aim/purpose.44 Several publications presented data which were merged with non-IMG minority groups.20 21 30 34 36 Merged general comments were made about racial discrimination,10 20 21 30 34 36 othering,30 systemic neglect10 and differential attainment.10 Although we note merged data here for completeness, only results attributing directly to IMGs have been fully extracted and reported in this scoping review.

Discussion

This scoping review found that over the last 40 years, IMGs report consistent and common experiences related to inequitable workplace treatment. Publications from USA, Australia and UK featured prominently in our study. The vast majority of studies were qualitative in nature, allowing depth of personal understanding. Inequity experiences were often reported in conjunction with effects on IMGs’ well-being and/or impact on career trajectory. It is not surprising that most publications did not approach well-being in their methodology, as this was not a key search term used for this scoping review. However, a high proportion of publications commented on well-being in relation to inequitable treatment. This discrepancy suggests that numerous authors found these study findings noteworthy, although unexpected. The majority of publications proposed solutions for IMG workplace inequity.

This scoping review is the first of its kind to specifically address IMG-reported workplace inequity factors, such as discrimination, prejudice and bias. It identifies a link between perceived inequities and IMG reports of detrimental well-being and altered career trajectory. To further assist policymakers, we summarise the proposed solutions to IMG inequity, in tabulated form.

There is growing evidence that racial discrimination negatively impacts mental health, such as stress, anxiety and depression, in addition to poorer physical and general health.50–53 Notably, subtle acts of workplace racial mistreatment on a regular daily basis has been shown to contribute to psychological stress and poorer job satisfaction.11 50 Similar to our study, a scoping review addressing racism in healthcare found that ethnic minority staff experienced discrimination from colleagues and patients.54 However, the additional element of being foreign trained has not been explored in depth as an independent risk factor for inequitable treatment. The association between IMG workplace inequities and outcomes such as well-being and career trajectory is a relatively unstudied environment. We found that only three studies10 22 23 33 deliberately sought to link these concepts. Furthermore, there is a dearth of literature investigating the topic of IMG health. Most recently, an Australian study identified that IMGs report lower life satisfaction when compared with domestic counterparts.55 Important contributors included factors such as perceived financial security, peer support, community integration and job autonomy.55 Such findings corroborate the need for further exploration into IMG health and well-being.

This scoping review brings attention to a confronting but critical topic which deserves systemic attention by institutions globally. It is worth noting that although our study focusses on IMGs, there are a number of professions, particularly in healthcare, that rely on overseas graduates. Therefore, the results of this scoping review may interest a wide range of readers and professions. Proposed solutions may help policymakers review and consider current practices while providing a platform for discussion, debate and future change.

Further study is required to determine if the skew of data from USA and Australia is simply secondary to under-reporting in other countries. More research is needed to better understand experiences and origins of inequity and efficacy of proposed solutions. Relationships between IMG experiences, career attainment and mental health require further exploration and should be considered across different geopolitical locations and host countries. Future study in this arena will benefit from being undertaken using psychometrically validated instruments.

Notable limitations include the search restriction to three academic medical databases and a short section of GOOGLE SCHOLAR. Non-English written publications were excluded, thereby adding to our limitations. By deselecting merged data, we may have missed presenting important experiences which were shared with other non-IMG minority groups. Lastly, we found that there was a large number of editorials and comments from various authors voicing opinions about the subject. Although the origin of these authors was often unstated, it was clear that underlying emotions were strong and worth exploring in a separate study.

Conclusions

This scoping review finds that there is long-standing evidence that IMGs believe they are subject to inequitable workplace experiences and that these experiences have self-reported repercussions on well-being and career trajectory. Inadequate professional recognition, perceived lack of choice and marginalisation were most commonly reported experiences. Further study is warranted to investigate and substantiate these observed correlations and confirm how institutional policies and procedures can be modified to create more equitable workplaces for IMGs.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SJRH (primary reviewer): conceptualisation, design, methods, extraction, interpretation, reporting manuscript production and guarantor. KF (second reviewer): design, methods, extraction, interpretation, reporting and manuscript editing. BRN (third reviewer): oversight of content and extraction, reporting and manuscript editing.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: SJRH and BRN are international medical graduates. BRN is the Director of the Workplace Based Assessment (WBA) Program for International Medical Graduates at Hunter New England Health, Australia and chairs the WBA development group for the Australian Medical Council.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Australian Parliament House of Representatives Standing Committee of Health and Ageing . 2012. Lost in the labyrinth: report on the inquiry into registration processes and support for overseas trained doctors Available: https://www.aph.gov.au/parliamentary_business/committees/house_of_representatives_committees?url=haa/overseasdoctors/report.htm

- 2.The changing medical workforce . General medical Council [PDF]. 2020. Available: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/somep-2020-chapter-3_pdf-84686032.pdf [Accessed 16 Jan 2023].

- 3.Foreign-Trained Doctor are Critical to Serving Many U.S. Communities . American immigration Council [special report]. 2018. Available: https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/foreign-trained-doctors-are-critical-serving-many-us-communities [Accessed 16 Jan 2023].

- 4.International migration of doctors and nurses. In: International migration of doctors and nurses | Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators | OECD iLibrary. Paris: OECD, 2023. Available: oecd-ilibrary.org [accessed 28 May 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National medical workforce strategy: 2021-2031 . Australian government Department of health. 2021. Available: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2022/03/national-medical-workforce-strategy-2021-2031.pdf [Accessed 9 May 2022].

- 6.Zavlin D, Jubbal KT, Noé JG, et al. A comparison of medical education in Germany and the United States: from applying to medical school to the beginnings of Residency. Ger Med Sci 2017;15:Doc15. 10.3205/000256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Recent trends in international migration of doctors, nurses and medical students. In: Recent Trends in International Migration of Doctors, Nurses and Medical Students | OECD iLibrary. Paris: OECD, 2019. Available: oecd-ilibrary.org [accessed 28 May 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motala MI, Van Wyk JM. Experiences of foreign medical graduates (Fmgs), international medical graduates (Imgs) and overseas trained graduates (Otgs) on entering developing or middle-income countries like South Africa: a Scoping review. Hum Resour Health 2019;17:7. 10.1186/s12960-019-0343-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Haddad M, Jamieson S, Germeni E. International medical graduates' experiences before and after migration: A meta-Ethnography of qualitative studies. Med Educ 2022;56:504–15. 10.1111/medu.14708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakravorty I, Daga S, Sharma S, et al. Bridging the gap 2021-summary report. Sushruta J Health Policy Opinion 2021:1–52. 10.38192/btg21.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferdinand AS, Paradies Y, Kelaher M. Mental health impacts of racial discrimination in Australian culturally and linguistically diverse communities: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2015;15:401. 10.1186/s12889-015-1661-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filut A, Alvarez M, Carnes M. Discrimination toward physicians of color: A systematic review. J Natl Med Assoc 2020;112:117–40. 10.1016/j.jnma.2020.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for Scoping reviews (Prismascr): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Searight HR, Gafford J. Behavioral science education and the International medical graduate. Acad Med 2006;81:164–70. 10.1097/00001888-200602000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blain M-J, Fortin S, Alvarez F. Professional journeys of international medical graduates in Quebec: recognition, uphill battles, or career change. J Int Migr Integr 2017;18:223–47. 10.1007/s12134-016-0475-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musoke SB. Foreign doctors and the road to a Swedish medical license experienced barriers of doctors from non-EU countries [Dissertation]. Sweden: Södertörn University, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith D. Overseas doctors in the national health service. 1st edn. London: Policy Studies Institute, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell AU, Tabaei FH, Østergaard D, et al. Conditions for foreign doctors' clinical work assessed by Danish health care personnel, patients and foreign doctors. Ugeskr Laeger 2008;170:1833–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coombs AAT, King RK. Workplace discrimination: experiences of practicing physicians. J Natl Med Assoc 2005;97:467–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins K, Powell S, Safdar M, et al. GP Trainees' experiences of training. Clin Teach 2021;18:552–7. 10.1111/tct.13410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen P-C, Nunez-Smith M, Bernheim SM, et al. Professional experiences of international medical graduates practicing primary care in the United States. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:947–53. 10.1007/s11606-010-1401-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen P-C, Curry LA, Bernheim SM, et al. Professional challenges of non-U.S.-Born International medical graduates and recommendations for support during Residency training. Acad Med 2011;86:1383–8. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823035e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heponiemi T, Hietapakka L, Lehtoaro S, et al. Foreign-born physicians' perceptions of discrimination and stress in Finland: a cross-sectional questionnaire study. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:418. 10.1186/s12913-018-3256-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heponiemi T, Hietapakka L, Kaihlanen A, et al. The turnover intentions and intentions to leave the country of foreign-born physicians in Finland: a cross-sectional questionnaire study. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:624. 10.1186/s12913-019-4487-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawthorne L, Birrell B, Young D, et al. Rural Workforce Agency V. The Retention of Overseas Trained Doctors in General Practice in Regional Victoria. Victoria: Rural Workforce Agency, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fiscella K, Roman-Diaz M, Lue BH, et al. 'Being a foreigner, I may be punished if I make a small mistake': assessing transcultural experiences in caring for patients. Fam Pract 1997;14:112–6. 10.1093/fampra/14.2.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bendfeldt F, Armstrong M. IMG residents’ views on experiences during psychiatric training. Int J Ment Health 1998;27:96–105. 10.1080/00207411.1998.11449437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woods SE, Harju A, Rao S, et al. Perceived biases and prejudices experienced by international medical graduates in the US post-graduate medical education system. Med Educ Online 2006;11:4595. 10.3402/meo.v11i.4595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neiterman E, Bourgeault IL. The shield of professional status: comparing internationally educated nurses' and international medical graduates' experiences of discrimination. Health (London) 2015;19:615–34. 10.1177/1363459314567788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woolf K, Rich A, Viney R, et al. Perceived causes of differential attainment in UK postgraduate medical training: a national qualitative study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e013429. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Symes HA, Boulet J, Yaghmour NA, et al. International medical graduate resident wellness: examining qualitative data from J-1 Visa physician recipients. Acad Med 2022;97:420–5. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stewart E, Nicholas S. Refugee doctors in the United Kingdom. BMJ 2002;325:S166. 10.1136/bmj.325.7373.s166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laird LD, Abu-Ras W, Senzai F. Cultural citizenship and belonging: Muslim International medical graduates in the USA. J Muslim Minor Aff 2013;33:356–70. 10.1080/13602004.2013.863075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Humphries N, Tyrrell E, McAleese S, et al. A cycle of brain gain, waste and drain - a qualitative study of non-EU migrant doctors in Ireland. Hum Resour Health 2013;11:63. 10.1186/1478-4491-11-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jirovsky E, Hoffmann K, Maier M, et al. "Why should I have come Here?"--A qualitative investigation of migration reasons and experiences of health workers from sub-Saharan Africa in Austria. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:74. 10.1186/s12913-015-0737-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klingler C, Marckmann G. Difficulties experienced by migrant physicians working in German hospitals: a qualitative interview study. Hum Resour Health 2016;14:57. 10.1186/s12960-016-0153-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marcus K, Purwaningrum F, Short S. Towards more effective health workforce governance: the case of overseas-trained doctors. Aust J Rural Health 2021;29:52–60. 10.1111/ajr.12692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zawawi AN, Al-Rashed AM. The experiences of foreign doctors in Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study of the challenges and retention motives. Heliyon 2020;6:e03901. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vamos M, Watson N. Coming on board: the assessment of overseas trained psychiatrists by the Royal Australian and New Zealand college of psychiatrists. Australas Psychiatry 2009;17:38–41. 10.1080/10398560802469736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Najeeb U, Wong B, Hollenberg E, et al. Moving beyond orientations: a multiple case study of the Residency experiences of Canadian-born and immigrant International medical graduates. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2019;24:103–23. 10.1007/s10459-018-9852-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Motala M, Van Wyk JM. Professional experiences in the transition of Cuban-trained South African medical graduates. S Afr Fam Pract (2004) 2021;63:e1–8. 10.4102/safp.v63i1.5390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schumann M, Sepke M, Peters H. Doctors on the move 2: a qualitative study on the social integration of middle Eastern physicians following their migration to Germany. Global Health 2022;18:78. 10.1186/s12992-022-00871-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Legido-Quigley H, Saliba V, McKee M. Exploring the experiences of EU qualified doctors working in the United kingdom: a qualitative study. Health Policy 2015;119:494–502. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hall P, Keely E, Dojeiji S, et al. Communication skills, cultural challenges and individual support: challenges of international medical graduates in a Canadian Healthcare environment. Med Teach 2004;26:120–5. 10.1080/01421590310001653982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McDonnell L, Usherwood T. International medical graduates - challenges faced in the Australian training program. Aust Fam Physician 2008;37:481–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Han G-S, Humphreys JS. Overseas-trained doctors in Australia: community integration and their intention to stay in a rural community. Aust J Rural Health 2005;13:236–41. 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2005.00708.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Appavoo S, Leichner P, Harper D. Foreign medical graduates and the Royal college examination: opinions of residents and Examiners. Acad Psychiatry 1983;7:197–201. 10.1007/BF03399886 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Durey A. Settling in: overseas trained Gps and their spouses in rural Western Australia. Rural Society 2005;15:38–54. 10.5172/rsj.351.15.1.38 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deitch EA, Barsky A, Butz RM, et al. Subtle yet significant: the existence and impact of everyday racial discrimination in the workplace. Human Relations 2003;56:1299–324. 10.1177/00187267035611002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:888–901. 10.1093/ije/dyl056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 2009;135:531–54. 10.1037/a0016059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0138511. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hamed S, Bradby H, Ahlberg BM, et al. Racism in Healthcare: a Scoping review. BMC Public Health 2022;22:988. 10.1186/s12889-022-13122-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Darboe A, Hawthorne L, Scott A, et al. Exploring life satisfaction difference between domestic and international medical graduates: evidence from a national longitudinal study. Int J Healthc Manag 2022:1–11. 10.1080/20479700.2022.2130641 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-071992supp001.pdf (60KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-071992supp002.pdf (151.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.