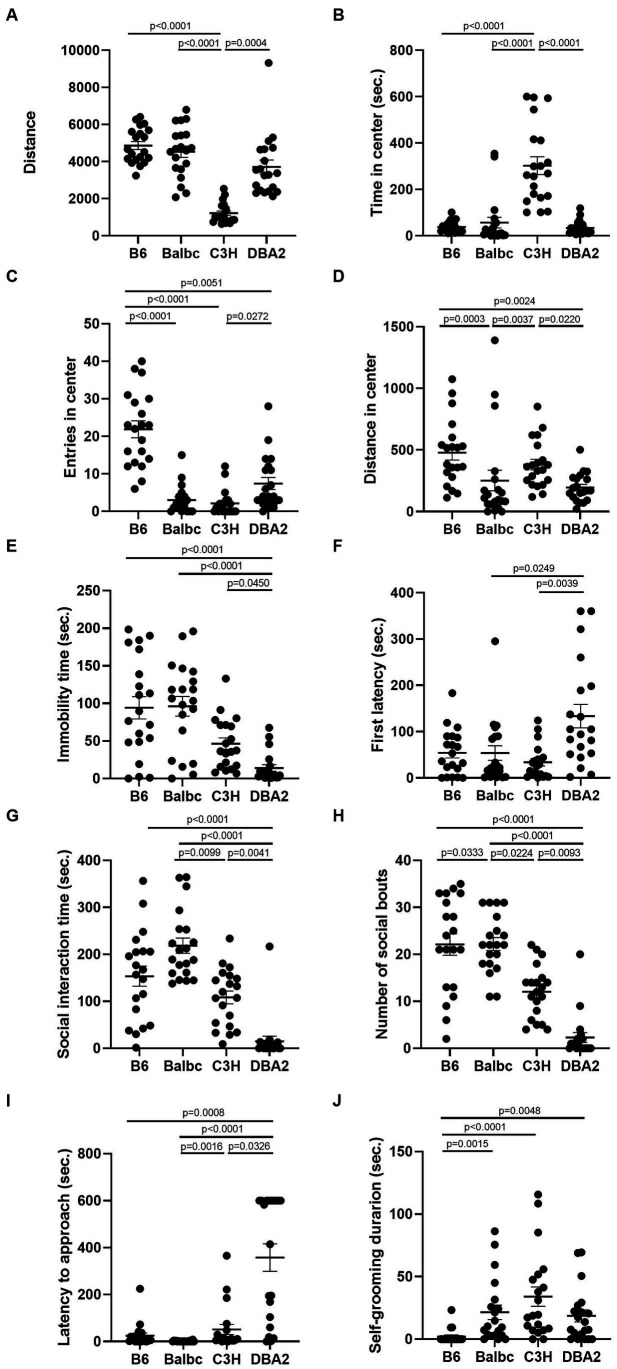

Figure 8.

Combining female data from both estrus and diestrus stages revealed many behavioral differences among the four strains. (A) The total travel distance of female mice among four different strains in the open-field test (H (3) = 48.75, p < 0.0001). (B) The time of female mice among four different strains in the center area of the open-field test (H (3) = 40.78, p < 0.0001). (C) The number of female mice among four different strains entered the center area of the open-field test (H (3) = 45.46, p < 0.0001). (D) The distance of female mice among four different strains in the center area of the open-field test (Diestrus: H (3) = 24.95, p < 0.0001). (E) The immobile time of female mice among four different strains in the forced-swimming test (H (3) = 28.39, p < 0.0001). (F) The latency to immobility of female mice among four different strains in the forced-swimming test (H (3) = 13.76, p = 0.0033). (G) The social interaction time of female mice among four different strains in the resident-intruder assay (H (3) = 46.00, p < 0.0001). (H) The number of social bouts of female mice among four different strains in the resident-intruder assay (H (3) = 42.47, p < 0.0001). (I) The latency of the female mice approaching the intruder among four different strains in the resident-intruder assay (H (3) = 49.10, p < 0.0001). (J) The self-grooming time of female mice among four different strains in the resident-intruder assay (H (3) = 25.65, p < 0.0001). Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s Multiple comparisons, Mean ± S.E.M. (n = 20 for each group, 10 mice tested in both estrus and diestrus stages).