Abstract

Background:

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC) is a rapidly fatal cancer with a median survival of a few months. Enhanced therapeutic options for durable management of ATC will rely on an understanding of genetics and the role of the tumor microenvironment. The prognosis for patients with ATC has not improved despite more detailed scrutiny of underlying tumor genetics. Pericytes in the microenvironment play a key evasive role for thyroid carcinoma (TC) cells. Lenvatinib improves outcomes in patients with radioiodine-refractory well-differentiated TC. In addition to the unclear role of pericytes in ATC, the effect and mechanism of lenvatinib efficacy on ATC have not been sufficiently elucidated.

Design:

We assessed pericyte enrichment in ATC. We determined the effect of lenvatinib on ATC cell growth cocultured with pericytes and in a xenograft mouse model from human BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cells coimplanted with pericytes.

Results:

ATC samples were significantly enriched in pericytes compared with normal thyroid samples. BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cells were resistant to lenvatinib treatment shown by a lack of suppression of MAPK and Akt pathways. Moreover, lenvatinib increased CD47 protein (thrombospondin-1 [TSP-1] receptor) levels over time vs. vehicle. TSP-1 levels were downregulated upon lenvatinib at late vs. early time points. Critically, ATC cells, when cocultured with pericytes, showed increased sensitivity to this therapy and ultimately decreased number of cells. The coimplantation in vivo of ATC cells with pericytes increased ATC growth and did not downregulate TSP-1 in the microenvironment in vivo.

Conclusions and Implications:

Pericytes are enriched in ATC samples. Lenvatinib showed inhibitory effects on BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cells in the presence of pericytes. The presence of pericytes could be crucial for effective lenvatinib treatment in patients with ATC. Degree of pericyte abundance may be an attractive prognostic marker in assessing pharmacotherapeutic options. Effective durable management of ATC will rely on an understanding not only of genetics but also on the role of the tumor microenvironment.

Keywords: anaplastic thyroid cancer, pericyte, lenvatinib, PDGFR-β, BRAFV600E

Introduction

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC) is typically fatal with a median survival time of 4 months.1–4 The prognosis and treatment for patients with ATC have not improved despite a more detailed scrutiny of underlying tumor genetics. Enhanced therapeutic options for durable management of ATC will rely on an understanding of both ATC genetics and the role of the tumor microenvironment in facilitating aggressive biology.

In the past several decades of thyroid carcinoma (TC) research, important advances with translational potential were discovered for ATC, including genetic alterations in BRAF, RAS, TP53, and TERT. The concept of de novo ATC versus evolution from well-differentiated TC is still controversial, with examples derived from tumors with variable genetics, including carcinomas traditionally associated with one genetic anomaly alone. The most common mutation associated with papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), BRAFV600E mutation, was found to drive tumor initiation5 in PTC.6–8

This mutation has also been associated with ATC, a tumor that rarely is associated with solo mutations. BRAFV600E is also known to modulate the tumor microenvironment in TC.9,10 However, the lack of significant improvement for the overall survival of patients with ATC over the past three decades should be noted.4,11,12 Despite being a rare cancer, given our knowledge of tumor genetics, more rational and effective therapeutics for ATC should be achievable. Lenvatinib is an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) targeting VEGFR-1-3, FGFR-1-4, RET, c-KIT, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β (PDGFR-β).13 Lenvatinib improves progression-free survival in patients with radioiodine-refractory TC14 with some effect in ATC.15

In the tumor microenvironment, pericytes express tyrosine kinases,16,17 play a key role in different mechanisms,18–20 and secrete thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) and TGF-β1.21 Pericytes are heterogeneous cell subpopulations with diverse gene expression profiles.17,22–24 Many markers for pericyte were proposed, including PDGFR-β.17,24–27

We have recently reported a first preclinical model of human thyroid derived-pericytes.16 High pericyte abundance correlated with PTC harboring genetic complexities, which may influence pericyte biology.16 Our study suggested that pericytes supported growth and survival of poorly differentiated and refractory PTC-derived cells.16 The inhibitory effects of lenvatinib were stronger in pericytes than in PTC-derived cells, perhaps due to the higher expression levels of PDGFR-β in pericytes.16

The role of pericytes in ATC is not yet investigated and will represent an important achievement in TC biology for precision medicine. In this study, we assessed pericyte abundance in ATC clinical samples as well as normal thyroid (NT) samples by scoring pericyte abundance using our previously published gene signature.16 We analyzed the interaction between ATC cells and pericytes by a coculture in vitro system of a heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cell line and pericytes. Moreover, we have established the first patient-derived xenograft mouse model from the coimplantation of a human BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cell line and pericytes to assess the effects of lenvatinib on ATC growth and pericyte density in the tumor microenvironment.

Materials and Methods

Pericyte abundance score in ATC and NT clinical samples

To determine the association between pericyte abundance and clinical–pathological factors in ATC, we performed analysis on an ATC RNA-seq data set28 that included RNA-seq data of 11 ATC and 4 NT samples. We estimated the relative pericyte abundance (delta score) according to our previous methods.16 This study does not involve human subjects, so it does not require institutional review board committee approval.

Cell culture and authentication

We used authenticated (by short tandem repeat [Genetica, USA]) human ATC cell lines (SW1736 and hTh7) analysis. We also used short-term cultures of pericytes that we have recently established.16 The use of these cell lines was approved by the institutional committee on microbiological safety (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA). SW1736 is an ATC cell line harboring heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E mutation that was kindly provided by N.E. Heldin (University of Uppsala, Uppsala, Sweden). hTh7 is an ATC cell line harboring RAS mutation (p.Q61R) that was kindly provided by the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus (USA; Cancer Center, tissue culture).

All cells were grown in 4.5 g/dL DMEM (catalog No. 10-013-CV; Corning, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; catalog No. S11550; Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, GA, USA), ampicillin/streptomycin antibiotic and 100 × antimycotic solution (Corning). Cells were grown according to our previous materials and methods.16

Drug treatment

We used lenvatinib (catalog No. S1164; Selleck Chemicals, USA) dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; vehicle) (Sigma) according to manufacturer's instructions to produce 10 mM stock solution. We diluted the drug as previously published.16 All assays were performed in at least 3 independent experiments in the presence or absence of recombinant human PDGF-BB (C199, Novoprotein, NJ, USA, or 220-BB-010, R&D Systems, USA) protein dissolved to produce 100 μg/μL stock solution with a final concentration of 20 ng/mL. Detailed information is provided in the Supplementary Materials and Methods S1.

Western blotting

Detailed information (including antibodies used) is provided in the Supplementary Materials and Methods S1. All assays were performed by at least three independent replicate measurements.

Drug sensitivity assay

To evaluate the efficacy of lenvatinib on the SW1736 cell line, cells were seeded at 10,000 cells/well in 96-well plate in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were counted on day 0 to obtain a baseline number of cells. At almost 90% confluency, the cells were treated with different concentrations of lenvatinib for 48 hours in the presence of 0.2% FBS DMEM at final 2% DMSO. To determine relative dose–response, we used the following concentrations of lenvatinib: 0, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 50, and 100 μmol/L.

Floating cells were removed and the viability of the adherent cells was calculated using Celigo image cytometer (Nexcelom, USA) with 2 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI) reagent (catalog No. 556463; BD Biosciences, USA) and 6 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 (catalog No. CS1-0128-5mL; Nexcelom) diluted in DMEM with 0.2% FBS (100 μL per well of 96-well plate) for 30 minutes. All cells were stained with Hoechst 33342, and nonviable (dead) cells were differentially stained with PI. The lenvatinib concentration that caused inhibition of 50% cell viability (IC50) was determined from the dose–response curves using GraphPad Prism 8 software (Boston, MA, USA). The percentage of cells was determined to the day 0 (baseline) pretreated cells. All samples were assessed in quadruplicates.

Coculture assays

SW1736 and hTh7 cell lines were engineered to express mCherry (red signal) vector described previously.21 SW1736 cells and thyroid-derived pericytes were seeded at low density at either 10,000 or 1000 cells per well in 6-well or 48-well plates. hTh7 cells and thyroid-derived pericytes were seeded at low density at either 1000 or 5000 cells per well in 48-well plates. After 24 hours, cells were treated for 48 hours with 4 μM lenvatinib. Adherent cells were imaged (magnification = 20 × ) using Nikon microscope with NIS Element BR version 4.20 imaging software (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and visually counted (using 1 field, 20 × ) every 24 hours.

ATC-derived cell lines expressed mCherry (red color) fluorescence versus pericytes (no color expression). Data were normalized to day 0 (baseline) for each condition and plotted as fold change. Fold change was calculated using Excel worksheet; statistical analysis and graphical representations were carried out by GraphPad Prism 8 software. All assays were performed in at least 2–3 replicate measurements from 2 independent experiments.

Xenograft mouse model

All animal work (protocol No. 069-2020) was approved and performed in accordance with federal, local, and institutional guidelines (IACUC) at BIDMC (Boston, MA). SW1736 cells and pericytes were grown in 10% FBS DMEM at 37°C with 5% CO2. Before implantation, SW1736 ATC cells and pericytes were trypsinized, centrifuged, and suspended in FBS-free DMEM to obtain a cell suspension concentration at 1 × 106/50 μL each. For the cell coimplantation, we used 1 × 106/50 μL of both SW1736 cells and pericytes in total 50 μL of serum-free DMEM.

The cells were kept on ice until implantation. Cells were injected along with 50 μL Matrigel (catalog No. 356230; Corning) into the subcutaneous spine concavities of 9-week-old female NSG mice (strain name: NOD.Cg-Prkdc scid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ; stock No.: 005557; n = 5 per group).

Ultrasound and color Doppler

SW1736 xenograft tumor growth was monitored weekly using microultrasound (T3200; Terason, USA). After initial baseline (pretreatment), mice (both BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cells alone and BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cells coimplanted with pericytes groups) were randomly divided into two subgroups to be treated with vehicle or lenvatinib to ensure equivalent tumor sizes among animals. Weekly follow-up scans were performed until study completion. In brief, mice were anesthetized using inhaled isoflurane administered through precision vaporizer.

Mice were then placed prone on a warmed ultrasound stage, where the fur overlying the tumor and surrounding area (from occipital bone to suprascapular region) was removed using hair depilatory cream. Prewarmed ultrasound coupling gel and high-frequency transducer (40 MHz, MS550) were used to locate the tumor. Images for linear measurement were obtained in B-mode. Color Doppler was used to obtain images of tumor blood flow. Images were obtained first in sagittal, then transverse planes. Images were saved for analysis after scanning was completed. A single individual (blinded to treatment groups) performed all ultrasonography and captured subsequent images.

The maximal height and width (in mm, roughly perpendicular to each other) were recorded as linear measurements from both sagittal and transverse views in B-mode. The following formula was used to obtain an estimate of tumor volume: V = π/6 × L × W × H; V = volume, L = length, W = width, and H = height. We used the data of W and H from the transverse view, while the L measurements were from the sagittal view. Vascular patterns in uploaded color Doppler images were examined using NIH Image J software (NIH, MD, USA). Blue indicates flow away from the transducer and red indicates flow toward the transducer.

Lenvatinib preparation for mouse treatment

For in vivo studies, drug suspension was prepared for lenvatinib (catalog No. FC71772; Biosynth Carbosynth, USA) at 30 mg/mL in autoclaved distilled H2O supplemented with 0.5% methylcellulose. Vehicle was filtered (0.41 μm) and then freshly (every day) prepared drug suspensions were immediately used. Drug dosage was adjusted based on weekly mouse body weight during treatment. Treatments with lenvatinib or vehicle were started 9 weeks after tumor cell implantation and performed for 3 weeks. Mice were dosed once daily for 3 weeks with vehicle (control) or lenvatinib (100 mg/kg) by oral gavage using a sterile feeding needle (catalog No. 01-208-87; Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Histology and immunohistochemistry

All tissue samples (injected samples on mice with SW1736 cells or SW1736 cells along with pericytes) were fixed with 10% buffered formalin phosphate and embedded in paraffin blocks. Histopathology evaluation was performed by a pathologist (P.M.S.) on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained tissue sections. All photographs were captured with an Olympus BX41 microscope and the Olympus Q COLOR 5 photograph camera (Olympus Corp., Lake Success, NY, USA), using the Twain software in Adobe Photoshop (7.0) and white balanced with the same methods for all images.

The immunohistochemistry marker expression levels were assessed semiquantitatively using the following scoring method: 0 (negative), 1+ (1–10% positive cells), 2+ (11–50% positive cells), and 3+ (>50% positive cells).29 The PAX8-positive number of cells in each of the four fields of view was counted and divided by the total number of cells (fold change) on the H&E staining. Detailed information is provided in the Supplementary Materials and Methods S1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using GraphPad Prism 8 software, JMP software, and R software. When the sample size was small and the distribution of the outcome was not known and could not be assumed to be approximately normally distributed, nonparametric tests were used. Student t test, Mann–Whitney U test, and one-way analysis of variance were used. Data are reported as the averaged value, and error bars represent the standard error of the average for each group. Results were considered significant at p-values <0.05.

Results

ATC samples show high pericyte enrichment score compared with NT samples

To estimate the abundance of cell subsets from tissue mRNA expression profiles, we evaluated the relative pericyte enrichment score. We have also assessed the expression level of the PDGF coding genes (PDGFA, PDGFB, PDGFC, and PDGFD) since PDGF ligands stimulate cancer stromal cells especially pericytes by binding to PDGFR-β.16,30,31 ATC samples showed significantly higher pericyte enrichment score than NT (p = 0.002) (Fig. 1A). Only PDGFD showed significantly higher mRNA expression levels in NT compared with ATC (p = 0.018) (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Relative pericyte abundance in ATC and NT samples. (A) Pericyte enrichment score in ATC (n = 11) and NT (n = 4) samples from RNA-seq data set. Each dot represents one sample, and the horizontal black bar represents the average enrichment score. Eleven ATC samples all showed a higher pericyte enrichment score than the four NT cases. The pericyte enrichment score was significantly higher in the ATC than in NT samples. Data are normalized log2 (count +1). Average enrichment scores were compared using the Mann–Whitney test (**p < 0.01). (B) Plot analysis of PDGF mRNA expression levels (PDGFA, PDGFB, PDGFC, and PDGFD) in ATC (n = 11) and NT (n = 4) from the RNA-seq data set. Data are normalized log2 (count +1). The data represent the mean ± standard error. Mann–Whitney test was used to compare averages (*p < 0.05). ATC, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; NT, normal thyroid; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor.

Dose–response analysis of lenvatinib in ATC cell line with heterozygous BRAFV600E mutation and effects on the intracellular signaling cascade

To assess the effect of lenvatinib on cell viability as well as downstream of PDGFR-β in the MAPK pathway and the PI3K pathway in ATC cells, we treated a BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cell line with lenvatinib and stimulated the cells with PDGF-BB for 48 hours. Lenvatinib inhibited viability of the BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cell line (the IC50 values: 31.79 μM without PDGF-BB, 16.42 μM with PDGF-BB) (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, lenvatinib effect was enhanced in the presence of PDGF-BB (with PDGF-BB vs. without PDGF-BB, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 in 5 and 10 μM doses, respectively) (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Lenvatinib effects on cell viability and intracellular signaling cascade in human heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cell line. (A) Dose–response curves with IC50 values for lenvatinib. Plot analysis of the lenvatinib sigmoidal dose–response curve in an ATC line at 48 hours. IC50 of lenvatinib was determined by measuring the inhibitory effects on ATC cell line viability. The cell line was grown in 0.2% FBS DMEM growth culture in 96-well plates and treated with lenvatinib or vehicle (2% DMSO) ± PDGF-BB (20 ng/mL). Each data point represents the mean ± standard error of four replicate measurements (two-way ANOVA, and Bonferroni correction test for multiple comparisons, ***p < 0.001). (B–E) Western blot analysis of protein expression levels in a BRAFWT/V600E-ATC SW1736 cell line. After 24 hours of seeding, cells were treated for 6 or 48 hours. The BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cell line was stimulated by PDGF-BB (20 ng/mL) and treated with lenvatinib or vehicle (2% DMSO). The tubulin of t-MEK1/2 is the same of the tubulin in the Western blot images of t-Akt. ANOVA, analysis of variance; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; FBS, fetal bovine serum.

We previously reported the inhibitory effects of lenvatinib in thyroid-derived pericyte cell survival.16 When we evaluated the intracellular signaling, the BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cell line did not show significant changes in the phosphorylated (p) PDGFR-β levels across all conditions, even when stimulated by PDGF-BB (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. S1). Besides, total PDGFR-β expression was not changed significantly under PDGF-BB stimulation or lenvatinib treatment (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. S1). Considering that the BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cell line shows low protein levels of p-PDGFR-β and does not respond to PDGF-BB stimulation, it is suggested that BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cells may not elicit any autocrine stimulation of PDGFR-β by PDGF-BB.

Moreover, PDGF-BB stimulation did not affect the drug efficacy of lenvatinib on protein expression of the PDGFR-β downstream factors, such as the kinases of PI3K pathway (phospho [p]-Akt and p-p70S6 kinase [K]) (Fig. 2C) and MAPK pathway (ERK1/2 and MEK1/2) (Fig. 2D and Supplementary Fig. S1) in BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cell line. These findings may suggest that BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cells may be resistant to lenvatinib.

We have also analyzed two membrane proteins that bind to TSP-1: CD36, a multifunctional protein that facilitates fatty acid uptake, and CD47, a protein that is involved in the escape from macrophage-mediated phagocytosis.32

When BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cells were treated with lenvatinib with PDGF-BB stimulation, there was increased p-SMAD3 (2.64-fold change upon 4 μM lenvatinib treatment at 48 hours vs. 6 hours, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2E and Supplementary Fig. S1). CD47 expression levels were upregulated at 48 hours versus 6 hours, whereas TSP-1 levels significantly downregulated upon lenvatinib at 48 hours versus 6 hours (Fig. 2E and Supplementary Fig. S1). CD36 levels showed no change over time.

All densitometry results are reported in Supplementary Figure S1.

Collectively, these results show that lenvatinib treatment may engage resistance to inhibit some intracellular signaling essential for ATC cell survival and growth.

Lenvatinib effects in a coculture system of heterozygous BRAFV600E-ATC-derived cell line and thyroid-derived pericytes

To analyze functional interactions between the BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cell line and pericytes and their impact on response to lenvatinib treatment in vitro, we established a coculture of a heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E-ATCmCherry cell line (red signal) and pericytes. The number of BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cells showed a trend toward increase in the coculture with thyroid-derived pericytes compared with the single culture although it was not significant (p = 0.087 at day 2) (Fig. 3A). The number of BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cells was significantly increased even upon treatment with lenvatinib compared with day 0 (p = 0.033) (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Lenvatinib inhibits tumor cell growth in a coculture system of human heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cell line and thyroid-derived pericytes. (A) Effects of the coculture on cell growth of thyroid-derived pericytes and BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cell line (SW1736). Heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cell line is detected by mCherry (red) fluorescence. Plot analysis of the fold change in number of cells normalized to baseline. While thyroid-derived pericytes were identified as cells without fluorescence. Cells were grown in 0.2% FBS DMEM. The results were validated by at least 2–3 replicates of 2 independent measurements. The data represent the mean ± standard error (one-way ANOVA). (B) Effects of lenvatinib treatment (4 μM) on cell growth of coculture of a BRAFWT/V600E-ATC SW1736 cell line and thyroid-derived pericytes. Cells were grown in 0.2% FBS DMEM. Plot analysis of the fold change in number of cells normalized to baseline (day 0). Day 0 means 24 hours after cell seeding, which was the day when lenvatinib was added in the cell cultures. The results were validated by at least three replicate measurements that were temporally independent than measurements in (A). The data show the mean ± standard error (one-way ANOVA, ***p < 0.001). (C) Representative photographs of coculture of a BRAFWT/V600E-ATC SW1736 cell line and thyroid-derived pericytes treated with lenvatinib or vehicle (2% DMSO) at day 0 (baseline, pretreatment) and day 2. The cells were grown during these treatments in 0.2% FBS DMEM. The BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cell line expressed mCherry (red color) fluorescence vs. pericytes (no color expression, yellow arrows). Magnification = 20 × .

Importantly, the inhibitory effects by lenvatinib on BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cells significantly occurred when these tumor cells were cocultured with thyroid-derived pericytes compared with the single culture (p = 0.0002) (Fig. 3B). Collectively, coculture of the BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cell line and pericytes tended to upregulate number of tumor cells. Pericytes enhanced lenvatinib efficacy on BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cells. In addition, the RAS-mutated ATC cell line showed a trend in reduction of phosphorylated PDGFR-β levels at 48 hours upon treatment with lenvatinib when stimulated by PDGF-BB or at 6 hours without PDGF-BB. Total PDGFR-β levels were significantly downregulated at 48 hours independently from lenvatinib treatment (Supplementary Fig. S2A, B).

We have also performed cocultures between the RAS-mutated ATCmCherry cell line (hTh7) (red signal) and pericytes and their impact on response to lenvatinib treatment (Supplementary Fig. S3A–C). The count of RAS-mutated ATC cells in coculture with thyroid-derived pericytes slightly increased compared with the single culture of ATC cells at day 2 (Supplementary Fig. S3A–C). Treatment with 4 μM lenvatinib showed a trend of decreased RAS-mutated ATC cell count at day 2 as compared with day 0 (Supplementary Fig. S3B) although it was not statistically significant (p = 0.231). Moreover, treatment with lenvatinib significantly reduced number of RAS-mutated ATC cells in the coculture with thyroid-derived pericytes at day 2 compared to that at day 0 (p = 0.011) (Supplementary Fig. S3B, C).

Assessment of lenvatinib effects in a xenograft mouse model from coimplanted human heterozygous BRAFV600E-ATC-derived cells and thyroid-derived pericytes

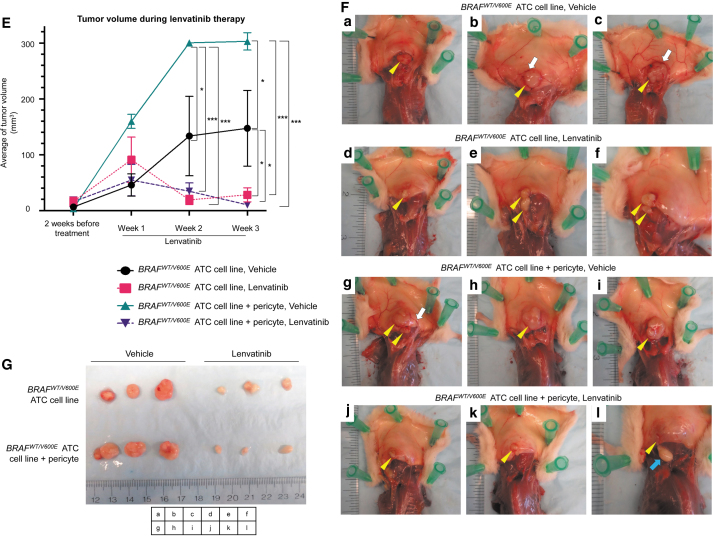

To assess the effect of coexistence of human ATC cells and human thyroid-derived pericytes on tumor growth, and their influence on lenvatinib therapy, we have established the first patient-derived xenograft mouse model from BRAFWT/V600E human ATC-derived cells and pericytes (Fig. 4A). Nine weeks after injection of the BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cells and pericytes, mice were treated with lenvatinib for 3 weeks (Fig. 4B). The ATC cells injected into the subcutaneous spine concavities grew as firm boundary-defined nodules with blood vessels flowing from skin into the tumor (Fig. 4F).

FIG. 4.

Effects of lenvatinib treatment in a xenograft mouse model of human heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E-ATC coimplanted with thyroid-derived pericytes. (A) Diagram of a xenograft mouse model using a human heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E-ATC SW1736 cell line with or without pericytes injection. (B) Experimental design of an in vivo preclinical model using a human heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E-ATC SW1736-derived cell line with or without injection of pericytes. The cells were implanted in 9-week-old male NSG mice (n = 5/group). Nine weeks later, tumor volume was estimated as baseline (pretreatment) by using ultrasound followed by random stratification of mice into two groups. Mice were treated once daily for 3 weeks with vehicle (control) or lenvatinib (100 mg/kg) by oral gavage. Xenograft human tumors in the subcutaneous spine concavities were assessed by ultrasound every week (pretreatment at 9 weeks postinjection; treatment at weeks 1, 2, and 3). (C) Representative images of B (brightness) mode and (D) color Doppler of ultrasound. Yellow arrows highlight the hypoechoic tumor in the subcutaneous spine concavities. In the color Doppler images, blue indicates flow going away from the transducer, and red indicates flow going toward the transducer. (E) Quantification of tumor volume calculated by using ultrasound at pretreatment, weeks 1, 2, and 3 after lenvatinib treatment. The data represent the mean ± standard error (one-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001) in each group. (F) At 3 weeks after treatment, the mice were sacrificed, and tumors observed in the spine concavities were resected. Yellow arrows highlight the tumor, and blue arrows highlight fat. Boundary-defined nodules with blood vessels (white arrows) flowing from skin into the tumor. (G) At 3 weeks after treatment, mice with coinjection of the BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cell line and pericytes showed more tumor growth than those injected with the BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cell line alone. Lenvatinib treatment showed a reduction in tumor size compared with the vehicle.

Tumor size was significantly larger in the mouse group with coimplantation of ATC cells along with pericytes treated with vehicle (300.27 ± 3.40 mm3) compared with that in the group with implanted ATC cells alone (133.38 ± 71.19 mm3) (2.25-fold changes, p = 0.012) at week 2 (Fig. 4C–E). In addition, tumor size was significantly larger in the mouse group with coimplantation of ATC cells along with pericytes treated with vehicle (302.89 ± 15.54 mm3) compared with that in the group with implanted ATC cells alone (147.35 ± 67.72 mm3) (2.06-fold changes, p = 0.014) at week 3 (Fig. 4C–E).

Remarkably, lenvatinib therapy significantly reduced xenograft tumor size in the BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cells coimplanted with human thyroid-derived pericytes compared with its vehicle (0.115-fold change, p < 0.0001, at week 2 [Fig. 4C–E] and 0.034-fold change, p < 0.0001, at week 3 [Fig. 4C–E]); but not in BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cells-only implanted group compared with its vehicle at week 2 (0.142-fold change, p = 0.186) (Fig. 4C–E), whereas a slight statistical significance (p = 0.044) was found at week 3 (0.191-fold change) (Fig. 4C–E). The resected tumors at week 3 are shown in Figure 4F and G.

Color Doppler sonography displayed some blood flow in the peritumoral area for 2 and 3 weeks in the group of BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cells coimplanted with pericytes treated with vehicle, whereas lenvatinib treatment substantially decreased tumor vascularity (Fig. 4D). Overall, our findings indicate that pericytes in the microenvironment may enhance ATC growth in vivo, while lenvatinib inhibits this process.

Immunohistochemical analysis of tumors from a xenograft mouse model of coimplanted human BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cells and pericytes during treatment with lenvatinib

We have assessed lenvatinib effects on the tumor microenvironment in vivo. Importantly, when we compared the ATC cells group treated with vehicle versus ATC cells and pericytes group treated with vehicle, the ratio of PAX8-positive tumor cells to total cells did not change (Fig. 5A, B, G). Remarkably, the number of PAX8-positive cells per field was significantly higher in the group of ATC-derived cells coimplanted with pericytes than in the ATC cells-only group (Fig. 5A, C, G), indicating that the increased tumor volume in the group with coimplanted ATC cells plus pericytes is not exquisitely determined by the volumetric amount of both ATC cells and pericytes but also due to tumor cell proliferation mechanisms.

FIG. 5.

Immunohistochemical analysis in the human heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E-ATC treated with lenvatinib. (A) Immunohistochemical staining of xenograft-resected tumors comprised a human heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E-ATC SW1736 cell line coimplanted with or without pericytes 3 weeks post-treatment with lenvatinib (100 mg/kg, once daily) or vehicle with PAX8, a thyroid follicular cell marker, and both PDGFR-β and CD90, pericytic markers, magnification = 200 × . (B) The ratio of PAX8-positive tumor cells to total cells was calculated as PAX8-positive cells divided by the total number of cells calculated from a serially sectioned H&E slide of the same tissue block. (C) PAX8-positive cell density was obtained by counting the PAX8-positive number of cells per field on an immunohistochemically stained slide of the human ATC cells group vs. a slide of the human ATC cells coimplanted with human pericytes group. (D) MIB1, CD31, and F4/80, magnification = 100 × or 200 × . (E) TSP-1 and TGF-β1, magnification = 200 × . (F) TSP-1 and TGF-β1, magnification = 1000 × . We use both expression scoring method: 0 (negative), 1 (<50% positive cells), and 2 (>50% positive cells), and intensity scoring method: absent (none), weak (<50% positive cells), and strong (>50% positive cells). (G) Immunohistochemical stains were assessed semiquantitatively using the following expression scoring method: 0 (negative), 1 (<50% positive cells), and 2 (>50% positive cells). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

PAX8 (thyroid follicular cell marker), PDGFR-β (pericytes marker), and CD90 (pericytes marker) were expressed in >50% of cells in the group of the xenograft mice with human BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cells or -ATC cells coimplanted with human thyroid-derived pericytes treated with vehicle (Fig. 5A, G), whereas lenvatinib treatment substantially decreased the number of both tumor cells and pericytes (Fig. 5A, G). Also, the number of positive cells for MIB1 (cell proliferation marker), CD31 (blood endothelial cells marker), and F4/80 (pan macrophage marker) substantially decreased during lenvatinib treatment compared with that with vehicle (Fig. 5D, G), suggesting that this TKI also effected vessel density as well as macrophage abundance in the tumor microenvironment.

Because our previous findings suggested a role for TSP-1 and TGF-β1 in the paracrine communication between BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cells and pericytes,21 we assessed the expression of the TSP-1/TGF-β1 axis in vivo in the microenvironment of the xenograft mouse of human BRAFWT/V600E-ATC treated with lenvatinib or vehicle (Fig. 5E, F). Lenvatinib therapy did not decrease the number of cells TSP-1-positive or TGF-β1-positive in the group of mice implanted with only ATC cells compared with vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 5E, F). It also appeared that lenvatinib downregulated TGF-β1 (but not TSP-1) expression in the xenograft mice coimplanted with human BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cells and human thyroid-derived pericytes (Fig. 5E, F).

Discussion

As ATC is such a deadly disease with limited treatment modalities, drilling down not only on lesional genetics but also on permissive mechanisms of tumor interactions with the microenvironment is essential. Here, we present the first patient-derived xenograft mouse model utilizing a human BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cell line and pericytes. Coimplantation of BRAFWT/V600E human ATC-derived cell line and pericytes increased the tumor volume compared with ATC cell implantation, and lenvatinib strongly inhibited tumor growth.

We have assessed the pericyte enrichment score for the relative pericyte abundance in the ATC samples. ATC samples showed a higher pericyte enrichment score than NT samples, suggesting that ATC has more pericytes in their microenvironment than NT. PTC with genetic complexity showed the highest pericyte abundance score.16 ATC showed numerous genetic alterations,33 and, therefore, our results suggest that activation of different oncogenic pathways and/or loss of tumor-suppressor genes may elicit tumor cell signals that are able to recruit pericytes to the tumor microenvironment.

Intriguingly, the inhibitory effect of lenvatinib on the viability of BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cells was not robust compared with that of vehicle, whereas pericytes were strongly sensitive to this therapy. BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cells expressed low protein levels of PDGFR-β, and PDGFR-β phosphorylation was not stimulated by PDGF-BB. Moreover, intracellular signaling kinases such as pERK1/2, pMEK1/2, p-Akt, p-p70S6K levels were not deregulated during lenvatinib treatment nor stimulated by PDGF-BB, suggesting that BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cells may be resistant to lenvatinib.

However, lenvatinib inhibited the cell viability of the BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cell line when cocultured with pericytes, suggesting that pericytes mediate the lenvatinib effects on the BRAFWT/V600E-ATC-derived cells. Lenvatinib inhibitory effects were also reported in a recent study on BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cell growth by targeting pericytes.16 Interestingly, RAS-mutated ATC cells were refractory to the lenvatinib treatment; the hTh7 cell line that we used harbored RAS mutation (p.Q61R), TERT mutation, TP53 mutation (p.G245S), and many other mutations,34 suggesting that these genetic alterations may elicit drug resistance to this TKI. Therefore, alternative therapeutic options will be needed for RAS-mutated ATC that show such genetic complexities.

The density of PAX8-positive cells was higher in the coimplantation group than in single-cell type implantation, suggesting that the increase of tumor volume of the cell coimplantation was not due to the number of injected cells (tumor cells + pericytes) or pericytes proliferation but due to the proliferation of the ATC cells. Colorectal tumor cells cocultured with pericytes induced pericyte cytokine secretion, which elicited tumor cell proliferation and chemoresistance35; pericytes expressed TGF-β1 and the pericytes/colorectal cell coculture system secreted high levels of TGF-β1, which triggered an autocrine regulatory mechanism.35

Importantly, TGF-β1 is a critical factor for immune suppression.36 Therefore, pericyte-driven factor secretion might be a possible mechanism of the pericytes' promotional effect on tumor growth under coimplantation. Another possibility is that pericytes and surrounding basement membrane may establish a scaffold for tumor vessel growth,37 which contributes to tumor growth.

The expression of thyroid follicular cell marker (PAX8) and pericyte markers (e.g., PDGFR-β and CD90) in this model in vivo was downregulated during lenvatinib treatment, suggesting that this therapy affected both BRAFWT/V600E-ATC cells and pericytes (both from mouse and from coimplanted human pericytes) survival. Human ATC cells alone implanted in the xenograft mouse showed sensitivity to treatment with lenvatinib: the physiological mouse microenvironment is enriched in mouse (de novo) pericytes that express PDGFR-β.

Importantly, ATC cells express the ligand PDGF-BB; PDGFR-β receptor shows sequence similarities between mouse and human,38 thus suggesting a possible interaction between human ligand and mouse receptor. Pericytes activate phosphorylation of PDGFR-β in the presence of the PDGF-BB ligand and became sensitive to the treatment with lenvatinib.16 Furthermore, the decreased expression of the cell proliferation marker Ki67 (MIB1) in the presence of lenvatinib suggests its antiproliferative activity.

TSP-1 and TGF-β1 are critical factors in the TC microenvironment.9,21 Human ATC cells and adjacent cells in the vascular compartment, including mouse endothelial cells and pericytes, showed similar amounts of TSP-1 and TGF-β1 protein expression levels in the lenvatinib-treated xenograft tumor mice as compared with vehicle-treated mice. These results suggest that TSP-1 and TGF-β1 may mediate mechanisms of resistance to this particular TKI (lenvatinib), and, therefore, these proteins may be considered as potential therapeutic targets in addition to lenvatinib treatment.

In conclusion, pericytes are enriched in ATC samples. Critically, lenvatinib showed a significant inhibitory effect on cultured ATC cells in the presence of pericytes, but not in their absence. The presence of pericytes could be crucial for effective lenvatinib treatment in patients with ATC. Degree of pericyte abundance may be an attractive prognostic marker in assessing pharmacotherapeutic options. Effective durable management of ATC will rely on an understanding not only of genetics but also on the role of the tumor microenvironment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the authors whom we were not able to cite because of limited space.

Data Availability Statement

This research meets the ethics guidelines. Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated during the current study. RNA-seq data were downloaded from Supplementary Material at (https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12030680).

Authors' Contributions

Conception and design of the study were carried out by C.N. Writing the article was by A.I. and C.N. Editing the article was done by A.I., S.L., P.S., M.A., A.N., J.L., and C.N. Data analysis was carried out by A.I., S.L., P.S., M.A., and C.N.

Author Disclosure Statement

Authors have no conflicts to disclose relating to this article.

Funding Information

C.N. was awarded grant by the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health (1R01CA248031-01).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Lowe NM, Loughran S, Slevin NJ, et al. Anaplastic thyroid cancer: The addition of systemic chemotherapy to radiotherapy led to an observed improvement in survival—a single centre experience and review of the literature. ScientificWorldJournal 2014;2014:674583; doi: 10.1155/2014/674583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Swaak-Kragten AT, de Wilt JH, Schmitz PI, et al. Multimodality treatment for anaplastic thyroid carcinoma—treatment outcome in 75 patients. Radiother Oncol 2009;92(1):100–104; doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Siironen P, Hagstrom J, Maenpaa HO, et al. Anaplastic and poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma: Therapeutic strategies and treatment outcome of 52 consecutive patients. Oncology 2010;79(5–6):400–408; doi: 10.1159/000322640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ito K, Hanamura T, Murayama K, et al. Multimodality therapeutic outcomes in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: Improved survival in subgroups of patients with localized primary tumors. Head Neck 2012;34(2):230–237; doi: 10.1002/hed.21721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nikiforova MN, Kimura ET, Gandhi M, et al. BRAF mutations in thyroid tumors are restricted to papillary carcinomas and anaplastic or poorly differentiated carcinomas arising from papillary carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88(11):5399–5404; doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell 2014;159(3):676–690; doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Knauf JA, Ma X, Smith EP, et al. Targeted expression of BRAFV600E in thyroid cells of transgenic mice results in papillary thyroid cancers that undergo dedifferentiation. Cancer Res 2005;65(10):4238–4245; doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-05-0047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu D, Liu Z, Condouris S, et al. BRAF V600E maintains proliferation, transformation, and tumorigenicity of BRAF-mutant papillary thyroid cancer cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92(6):2264–2271; doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nucera C, Porrello A, Antonello ZA, et al. B-Raf(V600E) and thrombospondin-1 promote thyroid cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107(23):10649–10654; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004934107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xing M. BRAF mutation in papillary thyroid cancer: Pathogenic role, molecular bases, and clinical implications. Endocr Rev 2007;28(7):742–762; doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McIver B, Hay ID, Giuffrida DF, et al. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: A 50-year experience at a single institution. Surgery 2001;130(6):1028–1034; doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.118266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bible KC, Kebebew E, Brierley J, et al. 2021 American Thyroid Association Guidelines for management of patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2021;31(3):337–386; doi: 10.1089/thy.2020.0944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matsui J, Funahashi Y, Uenaka T, et al. Multi-kinase inhibitor E7080 suppresses lymph node and lung metastases of human mammary breast tumor MDA-MB-231 via inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor-receptor (VEGF-R) 2 and VEGF-R3 kinase. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14(17):5459–5465; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-07-5270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schlumberger M, Tahara M, Wirth LJ, et al. Lenvatinib versus placebo in radioiodine-refractory thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;372(7):621–630; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tahara M, Kiyota N, Yamazaki T, et al. Lenvatinib for anaplastic thyroid cancer. Front Oncol 2017;7:25; doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iesato A, Li S, Roti G, et al. Lenvatinib targets PDGFR-β pericytes and inhibits synergy with thyroid carcinoma cells: Novel translational insights. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021;106:3569–3590; doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Armulik A, Genove G, Betsholtz C. Pericytes: Developmental, physiological, and pathological perspectives, problems, and promises. Dev Cell 2011;21(2):193–215; doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shepro D, Morel NM. Pericyte physiology. FASEB J 1993;7(11):1031–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ribatti D, Nico B, Crivellato E. The role of pericytes in angiogenesis. Int J Dev Biol 2011;55(3):261–268; doi: 10.1387/ijdb.103167dr [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Armulik A, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Endothelial/pericyte interactions. Circ Res 2005;97(6):512–523; doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000182903.16652.d7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Prete A, Lo AS, Sadow PM, et al. Pericytes elicit resistance to vemurafenib and sorafenib therapy in thyroid carcinoma via the TSP-1/TGFβ1 axis. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24(23):6078–6097; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-18-0693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Etchevers HC, Vincent C, Le Douarin NM, et al. The cephalic neural crest provides pericytes and smooth muscle cells to all blood vessels of the face and forebrain. Development 2001;128(7):1059–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rajantie I, Ilmonen M, Alminaite A, et al. Adult bone marrow-derived cells recruited during angiogenesis comprise precursors for periendothelial vascular mural cells. Blood 2004;104(7):2084–2086; doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Iesato A, Nucera C. Tumor microenvironment-associated pericyte populations may impact therapeutic response in thyroid cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol 2021;1329:253–269; doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-73119-9_14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Krueger M, Bechmann I. CNS pericytes: Concepts, misconceptions, and a way out. Glia 2010;58(1):1–10; doi: 10.1002/glia.20898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Crisan M, Chen CW, Corselli M, et al. Perivascular multipotent progenitor cells in human organs. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009;1176:118–123; doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04967.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hirschi KK, Rohovsky SA, Beck LH, et al. Endothelial cells modulate the proliferation of mural cell precursors via platelet-derived growth factor-BB and heterotypic cell contact. Circ Res 1999;84(3):298–305; doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.3.298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ravi N, Yang M, Mylona N, et al. Global RNA expression and DNA methylation patterns in primary anaplastic thyroid cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(3):680; doi: 10.3390/cancers12030680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shaik S, Nucera C, Inuzuka H, et al. SCF(β-TRCP) suppresses angiogenesis and thyroid cancer cell migration by promoting ubiquitination and destruction of VEGF receptor 2. J Exp Med 2012;209(7):1289–1307; doi: 10.1084/jem.20112446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hellstrom M, Kalen M, Lindahl P, et al. Role of PDGF-B and PDGFR-beta in recruitment of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes during embryonic blood vessel formation in the mouse. Development 1999;126(14):3047–3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fredriksson L, Li H, Eriksson U. The PDGF family: Four gene products form five dimeric isoforms. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2004;15(4):197–204; doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lawler PR, Lawler J. Molecular basis for the regulation of angiogenesis by thrombospondin-1 and -2. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012;2(5):a006627; doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pozdeyev N, Gay LM, Sokol ES, et al. Genetic analysis of 779 advanced differentiated and anaplastic thyroid cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24(13):3059–3068; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-18-0373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Landa I, Pozdeyev N, Korch C, et al. Comprehensive genetic characterization of human thyroid cancer cell lines: A validated panel for preclinical studies. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25(10):3141–3151; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-18-2953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Navarro R, Tapia-Galisteo A, Martín-García L, et al. TGF-β-induced IGFBP-3 is a key paracrine factor from activated pericytes that promotes colorectal cancer cell migration and invasion. Mol Oncol 2020;14(10):2609–2628; doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Batlle E, Massagué J. Transforming growth factor-β signaling in immunity and cancer. Immunity 2019;50(4):924–940; doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baluk P, Hashizume H, McDonald DM. Cellular abnormalities of blood vessels as targets in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2005;15(1):102–111; doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang X, Wu X, Zhang A, et al. Targeting the PDGF-B/PDGFR-β interface with destruxin A5 to selectively block PDGF-BB/PDGFR-ββ signaling and attenuate liver fibrosis. EBioMedicine 2016;7:146–156; doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.03.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This research meets the ethics guidelines. Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated during the current study. RNA-seq data were downloaded from Supplementary Material at (https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12030680).