Key Points

Question

Is a contextual and cultural adaptation of the Unified Protocol (CXA-UP) more effective than waitlist control in treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and comorbid emotional disorders in individuals exposed to armed conflict?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 200 internally displaced persons, the CXA-UP showed significant decreases and large effect sizes on all measures of PTSD, anxiety, depression, and somatic complaints with effects maintained at 3-month follow-up.

Meaning

In this study, when adapted contextually and culturally, the CXA-UP significantly improved severe emotional disorders and PTSD in internally displaced persons living in violent contexts.

This randomized clinical trial assesses the efficacy of a cultural and contextual adaptation of the Unified Protocol in treating posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression compared to waitlist control in individuals exposed to armed conflict in Colombia.

Abstract

Importance

A transdiagnostic treatment, the Unified Protocol, is as effective as single diagnostic protocols in comorbid emotional disorders in clinical populations. However, its effects on posttraumatic stress disorder and other emotional disorders in individuals living in war and armed conflict contexts have not been studied.

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy of a cultural and contextual adaptation of the Unified Protocol (CXA-UP) on posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression compared to waitlist control in individuals exposed to armed conflict in Colombia.

Design, Setting, and Participants

From April 2017 to March 2020, 200 participants 18 years and older were randomly assigned to the CXA-UP or to a waitlist condition. CXA-UP consisted of 12 to 14 twice-a-week or weekly individual 90-minute face-to-face sessions. Outcomes were assessed at baseline, posttreatment, and 3 months following treatment. Analyses were performed and compared for all randomly allocated participants (intent-to-treat [ITT]) and for participants who completed all sessions and posttreatment measures (per protocol [PP]). The study took place at an outpatient university center and included individuals who were registered in the Colombian Victims Unit meeting DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, or depression or were severely impaired by anxiety or depression. Individuals who were receiving psychological therapy, were dependent on alcohol or drugs, were actively suicidal or had attempted suicide in the previous 2 months, had psychosis or bipolar disorder, or were cognitively impaired were excluded.

Intervention

CXA-UP or waitlist.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcomes were changes in anxiety, depression, and somatic scores on the Patient Health Questionnaire and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5.

Results

Among the 200 participants (160 women [80.0%]; 40 men [20.0%]; mean [SD] age, 43.1 [11.9] years), 120 were randomized to treatment and 80 to waitlist. Results for primary outcomes in the ITT analysis showed a significant pretreatment-to-posttreatment reduction when comparing treatment and waitlist on the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 scores (slope [SE], −31.12 [3.00]; P < .001; Cohen d, 0.90; 90% CI, 0.63-1.19), 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (slope [SE],−11.94 [1.30]; P < .001; Cohen d, 0.77; 90% CI, 0.52-1.06), PHQ-anxiety (slope [SE], −6.52 [0.67]; P < .001; Cohen d, 0.82; 90% CI, 0.49-1.15), and PHQ-somatic (slope [SE], −8.31 [0.92]; P < .001; Cohen d, 0.75; 90% CI, 0.47-1.04).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, significant reductions and large effect sizes in all measures of different emotional disorders showed efficacy of a single transdiagnostic intervention in individuals exposed to armed conflicts.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03127982

Introduction

Mental health problems in vulnerable populations in low- and-middle-income countries represent a significant challenge for demonstrating efficacy of psychological treatments. In war zones, refugees and internally displaced persons present with multiple emotional and behavioral problems and disorders, with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and mood disorders being the most common. These psychological difficulties can contribute to unemployment, economic hardships, and health problems, increasing the effects of previous and current traumatic events.1 Furthermore, internally displaced persons and refugees in conflict zones are at a higher risk of developing mental disorders because of repeated exposure to traumatic events.2 Research shows that when these disorders are not adequately treated, they tend to become chronic and lead to other problems.3,4

More than 60 years of armed conflict in Colombia has left nearly 9 million individuals registered in the Colombian Victims Unit.5 Many have been exposed directly or indirectly to extreme violent events or are under continuous threats. More than 8 million individuals have been displaced from their lands.6 They live in hostile urban environments, where many cannot meet basic needs, obtain employment,7 or secure food and shelter.8 These conditions have a pronounced negative impact on mental health and quality of life,9 resulting in a higher incidence of anxiety disorders, depression, and substance misuse.10,11,12 PTSD is 5.1 times more prevalent in internally displaced persons in Colombia than in the general population.13,14

Cognitive behavior therapy targeting single emotional disorders is effective in clinical populations15; however, its efficacy with individuals presenting with multiple diagnoses is hindered by the costs of training therapists and implementing treatments for each disorder. Transdiagnostic interventions, which simultaneously target multiple disorders, may help bridge the science-to-service gap. The Unified Protocol for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders16 is a single cognitive-behavior intervention targeting temperamental characteristics, particularly neuroticism and resulting emotion dysregulation, common to multiple emotional disorders. The UP has considerable support for treating emotional disorders, including anxiety and depression, and has shown to be as effective as single-disorder interventions in clinical populations,17 with large effect size reductions across several common emotional disorders.18 Although some case studies and open trials have shown promising results for UP as a treatment for PTSD,19,20 randomized clinical trials have not been conducted. Moreover, as this population’s cultural and contextual characteristics differ from the North American sample of the original protocol, a cultural adaptation of the UP is warranted. The present study evaluates the efficacy of a culturally adapted version of the UP (CXA-UP) for emotional disorders, disability, and quality of life in a group of individuals exposed to armed conflict in comparison to a waitlist condition.

Methods

Participants

A sample of 200 participants was recruited from among individuals exposed to armed conflict who were registered in the Colombian Victims Unit5 and living in Bogotá by way of public announcements, referrals from independent organizations, and word of mouth. Eligible participants were adults 18 years and older who met diagnostic criteria for PTSD, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, or major depressive disorder according to the Spanish 5.0.0 version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)21 or who met criteria for significant severity or impairment from anxiety or depression severity and impairment (scoring higher than 7 on the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale22 or Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale23). In an initial telephone contact, potential participants were informed about the study, queried for their interest in participating, and screened for alcohol dependency or current involvement in psychological therapy. Those not meeting initial exclusion criteria were invited to an in-person screening session where all inclusion criteria were assessed; baseline outcome measures were obtained; detailed information about the study, including potential risks and unintended outcomes, was provided; and written informed consent was obtained as approved by the University of Los Andes Institutional Review Board (code 656-657-2016). Additional exclusion criteria were active suicidal ideation or suicide attempts in the previous 2 months, psychosis, bipolar disorder, and cognitive impairment. Participants who met the inclusion criteria and were willing to participate were offered free therapy with transportation costs covered. The study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Procedures

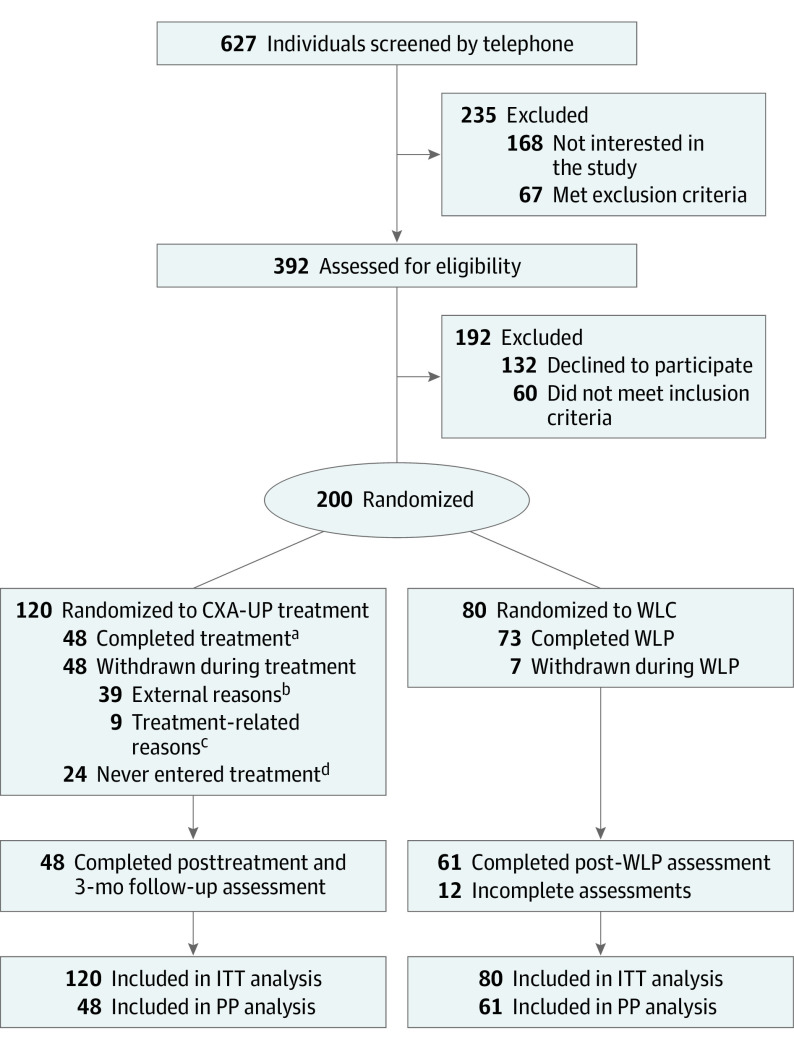

Study design and patient flow are summarized in the Figure. From April 2017 to March 2020, we recruited 200 participants and randomly allocated 120 to the treatment condition and 80 to the waitlist. The study consisted of 2 arms. The CXA-UP consisted of 12 to 14 individual face-to-face sessions with outcome measures taken at baseline, end of treatment, and 3-month follow-up. Participants assigned to the waitlist condition did not receive any intervention during the 6 weeks following baseline assessment but were informed that the UP intervention would commence in 6 weeks. Outcome measures were taken at the end of the 6-week wait period by assessors who were blinded to their group assignment.

Figure. Trial Profile.

CXA-UP indicates contextual/cultural adaptation of the Unified Protocol; ITT, intent-to-treat; PP, per protocol; WLC, waitlist control; WLP, waitlist period.

aCompleted treatment indicates that patients attended 100% of sessions.

bExternal reasons included transportation difficulties, moving to another city, or job commitments.

cTreatment-related reasons: 5 mentioned that sessions were too long, 4 felt uncomfortable during sessions.

dDropped out after assessment and before initial treatment session.

Randomization and Blinding

After screening and baseline assessment, a data manager—not involved as therapist or assessor—randomly assigned each new participant to each condition using a simple random formula, which recalculated the assignment independently for each participant. As this resulted in an imbalance in participants assigned to CXA-UP, after 20 randomized participants, subsequent allocation was based on a random number table.

Intervention

The treatment protocol was culturally adapted24 and translated from the original UP manuals25,26 into written therapist manuals and participant workbooks in Spanish. Examples of participants’ own emotional experiences were used to illustrate concepts within their cultural context and assignments adapted to their daily activities; text was replaced with graphic material in the workbook while core elements and order of modules of the original protocol were preserved as described in a previous publication.24 Treatment was delivered individually through 12 to 14 face-to-face sessions once to twice per week, with each session lasting for about 90 minutes over 6 to 12 weeks. For cultural reasons, an initial session was also added to allow participants to talk freely about their unique experiences, foster trust, and promote a collaborative relationship with the therapist. A case study providing a detailed description of the treatment protocol has been published previously.27

Therapists and Treatment Integrity

Therapists were 12 graduate clinical psychology students with at least 1 year of supervised experience in cognitive behavior therapy for emotional disorders. All therapists undertook 2 intensive training workshops on delivering the UP: the first by 1 of the developers of the original protocol and the second on the cultural adaptation by the principal investigator. In addition, video and audio recordings of treatment sessions with a study participant were discussed, and role-play was used to develop specific skills. Weekly supervision sessions, led by the principal investigator and 2 senior research associates, were also provided to all therapists.

Therapists were assessed for competence and mastery of the therapist’s manual at the end of each training workshop. All treatment sessions were audio recorded. Ten percent of sessions were randomly selected and rated for fidelity to the original treatment manual and competence by an original UP research team member using standardized fidelity ratings approved by the protocol developers and used in prior clinical trials of the UP.17 Specifically, therapists were rated on their ability to cover relevant session content, complete in-session exercises, and administer core treatment elements. Average treatment fidelity to the original manual was 86% across all rated sessions.

Assessments and Instruments

The primary outcomes were changes in anxiety, depression, and somatic symptoms as assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ),28 and changes in symptoms of PTSD, as measured by the PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PLC-5).29 Due to educational barriers, these instruments were read by independent assessors. Secondary outcomes included anxiety severity and level of interference, measured by the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale,22 depression severity, and level of interference as measured by the Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale.23 These measures were administered at baseline, at the beginning of each weekly session, at end of treatment, and at 3-month follow-up. In addition, changes in the Quality-of-Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire30 and an adaptation of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.031 were evaluated at baseline, posttreatment, and 3-month follow-up.

Sample Size Calculation

Power calculations conducted using G-Power32 version 3.1.9.7 with a moderate effect size (f2, 0.15), 2 tails, an α of .05, and statistical power of 0.95 yielded an estimated total of 90 participants. Since we expected attrition of up to 50% due to challenges often experienced by internally displaced persons (reliance on public transport, long journeys, threats to safety, and job instability), we aimed to recruit at least 150 participants to gather pretreatment and posttreatment measurements for 45 participants per group. As the attrition was higher than expected in the treatment group, we ultimately recruited 200 to attain the desired group sizes.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between treatment and waitlist groups on primary and secondary outcomes and demographic characteristics at baseline were evaluated using t tests and χ2 comparisons. Due to unequal group sizes, multilevel regression models were used to estimate the treatment effect, including treatment, time, and their interaction as predictors, with random intercepts for participants to represent intraindividual variance across time. Models were estimated using the lmer function from the lme4 package in R version 4.2.2 (R Foundation),33 P values and degrees of freedom were calculated using the Satterthwaite method34 using the jtool package in R version 2.2.0 (R Foundation). For treatment effects analysis, results of both intent-to-treat and per-protocol approaches were used and compared to address possible estimation biases generated by missing data. Intent-to-treat used all randomized participants, and per-protocol used participants who completed all sessions and posttreatment measures. Finally, multilevel models with time as a fixed effect and individual as a random effect were estimated using data from all participants completing treatment, including those receiving treatment after the waiting period (waitlist) with complete pretreatment, posttreamtent, and 3-month follow-up data to assess outcomes at follow-up. Effect sizes for the multilevel regression models were evaluated using the partial η2index and then transformed to Cohen d to facilitate comparison following IBM guidelines35 based on Cohen.36

Results

Sample Characteristics

There were 200 participants included (160 women [80.0%]; 40 men [20.0%]) with a mean (SD) age of 43.1 (11.9) years). Table 1 depicts baseline demographic characteristics, diagnoses, outcome measures, and initial comparisons between treatment and waitlist groups. We assessed the between-group equivalence of baseline outcomes using t tests. We did not find differences in primary or secondary outcomes, suggesting that both groups were comparable at baseline. We compared demographic variables between groups using χ2 and t tests and found that both groups were equivalent on all measures. According to the MINI, most patients met criteria for PTSD (146 [73%]) and major depressive disorder (128 [64%]), while 80 (40%) met criteria for panic disorder and 24 (12%) for generalized anxiety disorder. In addition, 133 (66%) participants met criteria for 2 or more diagnoses. Finally, 111 participants (58%) reported being under current life threats.

Table 1. Demographic and Baseline Characteristics.

| Variable | No. (%) | P valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 200) | Treatment (n = 120) | Control (n = 80) | ||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 43.1 (11.9) | 42.6 (11.7) | 43.9 (12.3) | .22 |

| Female | 160 (80.0) | 100 (83.3) | 60 (75.0) | .50 |

| Male | 40 (20.0) | 20 (17.7) | 20 (25.0) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 85 (42.5) | 56 (46.7) | 29 (36.3) | .30 |

| Married | 81 (40.5) | 42 (35.0) | 39 (48.8) | |

| Divorced | 34 (17.0) | 22 (18.3) | 12 (15.0) | |

| Have children | 164 (82.0) | 100 (83.3) | 64 (80.0) | .36 |

| Education level | ||||

| No formal education/elementary educationb | 49 (24.5) | 31 (25.8) | 18 (22.5) | .97 |

| High school | 85 (42.5) | 51 (42.5) | 34 (42.5) | |

| College/technical school | 66 (33.0) | 38 (31.7) | 28 (35.0) | |

| Unemployed | 133 (66.5) | 79 (65.8) | 54 (67.5) | .30 |

| Diagnoses (MINI) | ||||

| GAD | 25 (12.5) | 15 (12.5) | 10 (12.5) | .97 |

| PTSD | 148 (74.0) | 89 (74.2) | 59 (73.8) | >.99 |

| MDD | 129 (64.5) | 79 (65.8) | 50 (62.5) | .86 |

| PD | 80 (40.0) | 50 (41.7) | 30 (37.5) | .67 |

| ≥2 Diagnoses | 136 (68.0) | 83 (69.2) | 53 (66.3) | .48 |

| Outcome measures | ||||

| PCL-5, mean (SD) | 51.1 (15.0) | 51.4 (15.5) | 50.7 (14.3) | .72 |

| PHQ-somatic score, mean (SD) | 22.4 (4.7) | 22.7 (4.8) | 21.9 (4.5) | .23 |

| PHQ-depression score, mean (SD) | 24.6 (6.3) | 24.9 (6.6) | 24.3 (5.7) | .49 |

| PHQ-anxiety score, mean (SD) | 16.9 (3.2) | 16.8 (3.3) | 17.1 (3.0) | .51 |

| ODSIS score, mean (SD) | 13.2 (4.7) | 13.3 (4.6) | 13.1 (4.9) | .80 |

| OASIS score, mean (SD) | 12.5 (5.0) | 12.7 (5.0) | 12.3 (5.0) | .62 |

| QLESQ score, mean (SD) | 43.3 (8.4) | 43.0 (8.7) | 43.6 (8.0) | .63 |

| WHODAS score, mean (SD) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.8) | 1.2 (0.7) | .19 |

Abbreviations: GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; MDD, major depression disorder; MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; OASIS, Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale; ODSIS, Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale; PCL-5, posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5; PD, panic disorder; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; QLESQ, Quality-of-Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire; WHODAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale.

t Test and χ2 test.

No formal education and elementary education categories were combined to prevent identifiability of participants.

Of 200 randomized participants, 109 (54%) completed the assessment at the end of treatment. MINI diagnosis, baseline measures, demographic characteristics, or current threat did not predict missing data in the primary and secondary outcomes. The only significant predictor was group assignment, with a higher attrition rate for the treatment condition (72 participants [36%]) compared to waitlist (16 participants [8%]). Within the treatment group, 24 participants (12%) dropped out before initiating treatment, and 48 (24%) discontinued treatment. A telephone assessment was conducted to identify possible reasons for dropout. Forty-eight of 61 who were reachable (82%) stated that dropout was due to external reasons, such as time limitations and transportation difficulties affecting session attendance. Based on these results, we assumed that data were missing at random rather than due to symptom severity, treatment characteristics or therapeutic relationship. Missing data were addressed using maximum likelihood estimation.37

Summary of intent to treat and per protocol of observed means for primary and secondary outcomes at baseline, posttreatment, and follow-up for treatment condition and baseline and post–wait period for the waitlist condition are described in Table 2. Between-treatment slope differences and effect sizes for treatment and waitlist comparison for the intent-to-treat and per-protocol analyses are presented in Table 3. Results for primary outcomes in the intent-to-treat analysis show that the between-treatment effect for posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 was significant with a change of −31.12 (SE, 3.00; P < .001; Cohen d, 0.90; 90% CI, 0.63-1.19), the estimated effect for PHQ-9 was −11.94 (SE, 1.30; P < .001; Cohen d, 0.77; 90% CI, 0.52-1.06), for PHQ-anxiety was −6.52 (SE, 0.67; P < .001; Cohen d, 0.82; 90% CI, 0.49-1.15), and for PHQ-somatic was −8.31 (SE, 0.92; P < .001; Cohen d, 0.75; 90% CI, 0.47-1.04). For the secondary outcomes, the treatment effect for Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale was −10.02 (SE, 0.97; P < .001; Cohen d, 0.87; 90% CI,0.61-1.15); for Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale, −9.43 (SE, 0.93; P < .001; Cohen d, 1.01; 90% CI, 0.68-1.32); for QLESQ, 10.85 (SE, 1.53; P < .001; Cohen d, 0.54; 90% CI, 0.28-0.80); and for the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule, −1.01 (SE, 0.14; P < .001; Cohen d, 0.61; 90% CI, 0.32-0.90). Comparison of intent-to-treat and per-protocol analyses found that results and effect sizes for primary and secondary outcomes tended to be close, while intent-to-treat and per-protocol effect sizes and confidence intervals overlapped. Although effect sizes for the per-protocol approach tended to be slightly higher, all effect sizes were considered large.

Table 2. Observed Means for Primary and Secondary Outcomes.

| Mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CXA-UP | WL | |||

| ITT (n = 120) | PP (n = 48) | ITT (n = 80) | PP (n = 61) | |

| Primary outcomes | ||||

| PCL-5 score | ||||

| Pretreatment | 51.4 (15.5) | 50.4 (17.1) | 50.7 (14.3) | 51.5 (13.6) |

| Posttreatment | 15.3 (13.8) | 15.3 (13.8) | 46.4 (14.5) | 46.4 (14.5) |

| 3-mo Follow-up | 10.8 (14.6) | 10.8 (14.6) | NA | NA |

| PHQ-depression score | ||||

| Pretreatment | 24.9 (6.6) | 24.3 (6.4) | 24.3 (5.7) | 24.6 (6.8) |

| Posttreatment | 13.1 (6.7) | 13.1 (6.7) | 24.7 (6.5) | 24.7 (6.5) |

| 3-mo Follow-up | 12.9 (5.3) | 12.9 (5.3) | NA | NA |

| PHQ-anxiety score | ||||

| Pretreatment | 16.8 (3.3) | 16.7 (3.5) | 17.1 (3.0) | 17.4 (2.9) |

| Posttreatment | 9.87 (3.6) | 9.87 (3.6) | 16.9 (3.2) | 16.9 (3.2) |

| 3-mo Follow-up | 10.0 (3.9) | 10.0 (3.9) | NA | NA |

| PHQ-somatic score | ||||

| Pretreatment | 22.7 (4.8) | 22 (5.1) | 21.9 (4.5) | 21.8 (4.5) |

| Posttreatment | 14.3 (5.5) | 14.3 (5.5) | 22.1 (4.8) | 22.1 (4.8) |

| 3-mo Follow-up | 15.2 (4.6) | 15.2 (4.6) | NA | NA |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| ODSIS score | ||||

| Pretreatment | 13.3 (4.6) | 12.5 (4.4) | 13.1 (4.9) | 12.9 (5.0) |

| Posttreatment | 1.8 (3.1) | 1.8 (3.1) | 11.8 (5.4) | 11.8 (5.4) |

| 3-mo Follow-up | 2.6 (4.3) | 2.6 (4.3) | NA | NA |

| OASIS score | ||||

| Pretreatment | 12.7 (5.0) | 12.7 (4.1) | 12.3 (5.0) | 12.1 (4.9) |

| Posttreatment | 1.7 (2.7) | 1.7 (2.7) | 10.7 (4.1) | 10.7 (4.1) |

| 3-mo Follow-up | 3.0 (4.3) | 3.0 (4.3) | NA | NA |

| Q-LES-Q score | ||||

| Pretreatment | 43.0 (8.1) | 43.6 (9.3) | 43.6 (8.0) | 43.5 (8.2) |

| Posttreatment | 54.8 (7.2) | 54.8 (7.2) | 44.3 (8.2) | 44.3 (8.2) |

| 3-mo Follow-up | 58.1 (8.5) | 58.1 (8.5) | NA | NA |

| WHODAS score | ||||

| Pretreatment | 1.3 (0.8) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.7) |

| Posttreatment | 0.4 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.7) |

| 3-mo Follow-up | 1.0 (0.9) | 1.0 (0.9) | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: CXA-UP, contextual/cultural adaptation of the Unified Protocol; ITT, intent-to-treat; NA, not applicable; OASIS, Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale; ODSIS, Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale; PCL-5, posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PP, per protocol; Q-LES-Q, Quality-of-Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire; WHODAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale; WL, waitlist.

Table 3. Slope Difference Scores and Between-Condition Effect Sizes for Intent-to-Treat (ITT) and Per-Protocol (PP) Analyses.

| CXA-UP vs WL difference slope | Treatment effect size CXA-UP vs WL | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITT | PP | ITT | PP | |||||

| Slope (SE) | t Value | df a | Slope (SE) | t Value | df a | Cohen d (90% CI)b | Cohen d (90% CI)b | |

| Primary outcomes | ||||||||

| PCL-5 score | −31.12 (3.00)c | −10.35 | 150 | −29.89 (3.24)c | −9.21 | 109 | 0.90 (0.63-1.19) | 0.95 (0.63-1.28) |

| PHQ-depression score | −11.94 (1.30)c | −9.17 | 146 | −11.33 (1.39)c | −8.14 | 107 | 0.77 (0.52-1.06) | 0.82 (0.49-1.15) |

| PHQ-anxiety score | −6.52 (0.67)c | −9.71 | 143 | −6.25 (0.72)c | −8.61 | 107 | 0.82 (0.56-1.09) | 0.87 (0.56-1.22) |

| PHQ-somatic score | −8.31 (0.92)c | −9.00 | 150 | −7.97 (0.99)c | −7.98 | 108 | 0.75 (0.47-1.04) | 0.80 (0.47-1.12) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||

| ODSIS score | −10.02 (0.97)c | −10.24 | 154 | −9.63 (1.06)c | −9.08 | 109 | 0.87 (0.61-1.15) | 0.95 (0.61-1.28) |

| OASIS score | −9.43 (0.93)c | −10.12 | 124 | −9.55 (0.94)c | −10.10 | 109 | 1.01 (0.68-1.32) | 1.09 (0.75-1.42) |

| QLESQ score | 10.85 (1.53)c | 7.06 | 140 | 10.48 (1.63)c | 6.41 | 109 | 0.54 (0.28-0.80) | 0.56 (0.28-0.87) |

| WHODAS score | −1.01 (0.14)c | −7.06 | 119 | −1.00 (0.14)c | −6.76 | 100 | 0.61 (0.32-0.90) | 0.65 (0.35-0.98) |

Abbreviations: CXA-UP, contextual/cultural adaptation of the Unified Protocol; OASIS, Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale; ODSIS, Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PCL-5, posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5; QLESQ, Quality-of -Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire; WHODAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale; WL, waitlist.

df and P values are derived with the Satterthwaite method.

The Cohen d effect sizes presented are transformations of η2 P to a more common effect size measure (interpretation: 0.2 small, 0.5 medium, 0.8 large).

P < .001.

Longitudinal within-model results for primary and secondary outcomes at pretreatment, posttreatment, and follow-up are depicted in Table 4. For all primary and secondary outcomes, the pretreatment vs posttreatment slope change tended to be close to the pretreatment vs follow-up slope change, confirming that the pretreatment-posttreatment effect was maintained over 3-month follow-up.

Table 4. Follow-Up Results for Primary and Secondary Outcomes.

| Pretreatment score | Pretreatment slope vs posttreatment slope | Pretreatment slope vs follow-up slope | Effect size | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | t Value | df a | Slope (SE) | t Value | df a | Slope (SE) | t Value | df a | Cohen d (90% CI)b | |

| Primary outcomes | ||||||||||

| PCL-5 score | 50.64 | 25.13 | 179 | −28.10 (2.56)c | −10.96 | 128 | −39.51 (2.56)c | −15.40 | 128 | 1.28 (1.01-1.56) |

| PHQ-somatic score | 21.92 | 34.69 | 174 | −5.77 (0.79)c | −7.24 | 127 | −6.57 (0.79)c | −8.32 | 126 | 0.62 (0.39-0.84) |

| PHQ-depression score | 24.71 | 29.32 | 162 | −8.41 (1.01)c | −8.34 | 127 | −11.64 (1.00)c | −11.64 | 126 | 0.91 (0.67-1.15) |

| PHQ-anxiety score | 16.84 | 34.16 | 172 | −5.04 (0.61)c | −8.19 | 128 | −6.67 (0.61)c | −10.93 | 127 | 0.84 (0.60-1.09) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||||

| ODSIS score | 12.71 | 21.03 | 178 | −8.43 (0.78)c | −10.78 | 127 | −10.40 (0.78)c | −13.23 | 127 | 1.12 (0.84-1.35) |

| OASIS score | 12.57 | 22.26 | 185 | −8.59 (0.74)c | −11.51 | 127 | −9.44 (0.74)c | −12.59 | 128 | 1.09 (0.86-1.39) |

| QLESQ score | 43.16 | 38.89 | 157 | 8.64 (1.27)c | 6.79 | 127 | 14.07 (1.27)c | 11.05 | 127 | 0.82 (0.58-1.06) |

| WHODAS score | 1.30 | 12.72 | 152 | −0.52 (0.13)c | −4.02 | 120 | −0.36 (0.12)c | −3.02 | 114 | 0.29 (0.07-0.55) |

Abbreviations: OASIS, Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale; ODSIS, Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale; PCL-5, posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; QLESQ, Quality-of -Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire; WHODAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale.

df and P values are derived with the Satterthwaite method.

The Cohen d effect sizes presented are transformations of η2 P to a more common effect size measure (interpretation: 0.2 small, 0.5 medium, 0.8 large).

P < .001.

Discussion

Our study evaluated the efficacy of adapting the UP to the cultural and contextual characteristics of individuals exposed to armed conflict and other related events and forced to abandon their lands and live in an urban environment. Previous studies of psychological interventions targeted to single disorders in low- and-middle-income countries showed moderate treatment effects that were not maintained at follow-up.38 Another transdiagnostic psychological intervention study in Colombia found mixed results.39 In comparison, our randomized waitlist-controlled trial yielded significant differences with large effect sizes between treatment and waitlist conditions and within all participants who completed treatment and 3-month follow-up. This result was observed for all measures of PTSD, anxiety, depression, somatic complaints, and disability and was accompanied by significant improvements in quality-of-life measures. For anxiety and depression, the effect size found was comparable to the medium-to-large effect sizes observed in UP randomized clinical trials with passive controls40 across more usual clinical populations, with similar results maintained over time as seen in previous studies.41 To our knowledge, our study is the first randomized clinical trial to demonstrate the efficacy of the UP in a sample of patients primarily diagnosed with PTSD in violent contexts with large effect sizes comparable to trauma-focused interventions.42

These outcomes could be attributed to several factors. First, the specific modules of the protocol target basic psychological processes common to different emotional disorders. Second, we adapted the original protocol maintaining integrity to core concepts and skills while using culturally appropriate language, personalized examples, and exercises tailored to cultural practices.43,44 Third, to address possible therapist bias and increase quality control and fidelity to original protocols, we conducted extensive training with and continuous supervision of therapists.

Limitations

Nevertheless, this study has limitations suggesting our results should be interpreted cautiously. First, there was high, albeit expected, attrition before and during treatment. This can be attributed to several possible causes. Most important among them is that internally displaced persons comprise a highly mobile population living in remote urban and unsafe locations. Therefore, these individuals experience public transportation difficulties and unstable job conditions leading to frequent lodging changes that constitute a barrier to treatment engagement and retention. This is supported by our finding that the main predictor of attrition was group assignment, with higher attrition rates in the treatment condition where participants had to travel to attend sessions, with 82% of dropouts attributing attrition to these external reasons. Furthermore, although the nearly 50% dropout rate could represent a possible estimation bias of our results, the average treatment effect and effect sizes overlapping between intent-to-treat and per-protocol analyses still suggest that our results were robust under a missing-at-random assumption. Second, while unequal groups sizes do not represent a threat to internal validity, as there was a true randomization, we addressed the possible threat to statistical inference by using multilevel regressions to assess differences, which addresses problems related to unequal group sizes. Third , answers to self-report measures could have been influenced by having been read to participants. Fourth, although using a waitlist control might produce an overestimation bias effect,45 the effect sizes for improvement in the treatment group are comparable to those observed in previous studies. Additionally, negative effects were not evaluated, as they have not been reported in previous studies with the UP.15,17,18,19 Fifth, to maximize internal validity, we conducted our study under highly controlled conditions with participants who lived in Bogotá. Therefore, the effects of our intervention may not generalize to similar individuals living in their territorial homeland within armed conflict zones.46

Conclusions

Considering the large number of individuals needing effective mental health intervention and the scarcity of mental health professionals in remote regions, especially in low- and-middle-income countries, demonstrating the efficacy of a brief, evidence-based psychological intervention targeting multiple problems under controlled conditions is a necessary condition prior to developing shorter and more precise scalable interventions available to larger segments of the population. Although randomized clinical trials are the gold standard for establishing the efficacy of interventions, they do not provide information on individual changes over time nor on differential response to treatment.47 As the UP comprises multiple modules, future research on differential response patterns by different individuals to specific intervention components through single-case experimental studies or group latent class trajectory analyses would give rise to more precise and efficient targeted treatments. Indeed, as we obtained repeated measures in all sessions, a subsequent step is to evaluate the efficacy of the intervention and individuals’ change along different points of the treatment. Identifying subgroups of individuals showing similar patterns of change related to the specific modules of the CXA-UP could help clarify not only mechanisms of change but, most importantly, help identify modifiable predictors of specific trajectories based on underlying psychological markers. This could lead to development of briefer modular interventions targeted to empirically derived individual psychological markers rather than diagnostic categories.48,49 Further research on the effectiveness of the CXA-UP provided by nonspecialized health workers with individuals living in their places of origin in community settings would improve scalability access and have a greater impact on economics and public mental health policy in low- and-middle-income countries.

Trial protocol

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Miller KE, Rasmussen A. War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(1):7-16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steel Z, Chey T, Silove D, Marnane C, Bryant RA, van Ommeren M. Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;302(5):537-549. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keller A, Lhewa D, Rosenfeld B, et al. Traumatic experiences and psychological distress in an urban refugee population seeking treatment services. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194(3):188-194. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000202494.75723.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siriwardhana C, Adikari A, Pannala G, et al. Prolonged internal displacement and common mental disorders in Sri Lanka: the COMRAID study. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e64742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colombian Government, Unit for Victims . Official Victims’ Registry Bogota D.C.: Colombian Government; 2022. Updated August 1, 2022. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.unidadvictimas.gov.co/es/registro-unico-de-victimas-ruv/37394

- 6.Shultz JM, Garfin DR, Espinel Z, et al. Internally displaced “victims of armed conflict” in Colombia: the trajectory and trauma signature of forced migration. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(10):475. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0475-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bozzoli C, Bruck T, Wald N. Self-employment and conflict in Colombia. J Conflict Resolut. 2013;57:117-142. doi: 10.1177/0022002712464849 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ibáñez AM, Moya A. Vulnerability of victims of civil conflicts: Empirical evidence for the displaced population in Colombia. World Dev. 2010;38:647-663. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.11.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniels JP. Mental health in post-conflict Colombia. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(3):199. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30068-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell V, Méndez F, Martínez C, Palma PP, Bosch M. Characteristics of the Colombian armed conflict and the mental health of civilians living in active conflict zones. Confl Health. 2012;6(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-6-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gómez-Restrepo C, Tamayo-Martínez N, Buitrago G, et al. Violence due to armed conflict and prevalence of mood disorders, anxiety, and mental disorders in the Colombian adult population. Article in Spanish. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 2016;45(suppl 1):147-153. doi: 10.1016/j.rcp.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peevey N, Flores E, Seguin M. Common mental disorders and coping strategies amongst internally displaced Colombians: a systematic review. Glob Public Health. 2022;17(12):3440-3454. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2022.2049343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lagos-Gallego M, Gutierrez-Segura JC, Lagos-Grisales GJ, Rodriguez-Morales AJ. Post-traumatic stress disorder in internally displaced people of Colombia: an ecological study. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2017;16:41-45. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2017.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards A, Ospina-Duque J, Barrera-Valencia M, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression symptoms, and psychosocial treatment needs in Colombians internally displaced by armed conflict: A mixed-method evaluation. Psychol Trauma. 2011;3:384-393. doi: 10.1037/a0022257 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJ, Sawyer AT, Fang A. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36(5):427-440. doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barlow DH, Allen LB, Choate ML. Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behav Ther. 2004;47(6):838-853. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barlow DH, Farchione TJ, Bullis, JR, et al. The unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders compared with diagnosis-specific protocols for anxiety disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(9):875-884. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakiris N, Berle D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Unified Protocol as a transdiagnostic emotion regulation based intervention. Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;72:101751. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varkovitzky RL, Sherrill AM, Reger GM. Effectiveness of the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot study. Behav Modif. 2018;42(2):210-230. doi: 10.1177/0145445517724539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hood CO, Southward MW, Bugher C, Sauer-Zavala S. A preliminary evaluation of the unified protocol among trauma-exposed adults with and without PTSD. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21):11729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheehan D, Janavs J, Baker R, et al. Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview. Spanish version 5.0.0. Ferrando L, Franco-Alfonso L, Soto M, Bobes-García J, Soto O, Franco L, Heinze G, trans. Published January 1, 2000.

- 22.Norman SB, Cissell SH, Means-Christensen AJ, Stein MB. Development and validation of an Overall Anxiety Severity And Impairment Scale (OASIS). Depress Anxiety. 2006;23(4):245-249. doi: 10.1002/da.20182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bentley KH, Gallagher MW, Carl JR, Barlow DH. Development and validation of the Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale. Psychol Assess. 2014;26(3):815-830. doi: 10.1037/a0036216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castro-Camacho L, Rattner M, Quant DM, González L, Moreno JD, Ametaj A. Contextual adaptation of the Unified Protocol for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders in victims of armed conflict in Colombia. Cognit Behav Pract. 2019;26:351-365. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barlow DH, Farchione TJ, Fairholme CP, et al. Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders: Therapist Guide. Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barlow DH, Ellard KK, Fairholme CP, et al. Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders: Workbook. Oxford University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castro-Camacho L, Moreno JD, Naismith I. Contextual adaptation of the Unified Protocol for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders in victims of armed conflict in Colombia: a case study. Cognit Behav Pract. 2019;26:366-380. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams J, Löwe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry . 2010;32:345-359. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(6):489-498. doi: 10.1002/jts.22059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29(2):321-326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Üstün TB, Kostanjsek N, Chatterji S, Rehm J; World Health Organization. Measuring Health and Disability: Manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0). Published June 16, 2012. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/measuring-health-and-disability-manual-for-who-disability-assessment-schedule-(-whodas-2.0) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175-191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67(1):1-4. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luke SG. Evaluating significance in linear mixed-effects models in R. Behav Res Methods. 2017;49(4):1494-1502. doi: 10.3758/s13428-016-0809-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.IBM . Relationship between partial eta-squared, Cohen’s F, and Cohen’s D. Accessed February 20, 2023. https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/effect-size-relationship-between-partial-eta-squared-cohens-f-and-cohens-d

- 36.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sullivan TR, White IR, Salter AB, Ryan P, Lee KJ. Should multiple imputation be the method of choice for handling missing data in randomized trials? Stat Methods Med Res. 2018;27(9):2610-2626. doi: 10.1177/0962280216683570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Purgato M, Gastaldon C, Papola D, van Ommeren M, Barbui C, Tol WA. Psychological therapies for the treatment of mental disorders in low- and middle-income countries affected by humanitarian crises. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7):CD011849. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011849.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonilla-Escobar FJ, Fandiño-Losada A, Martínez-Buitrago DM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral intervention for Afro-descendants’ survivors of systemic violence in Colombia. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carlucci L, Saggino A, Balsamo M. On the efficacy of the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;87:101999. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.101999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bullis JR, Fortune MR, Farchione TJ, Barlow DH. A preliminary investigation of the long-term outcome of the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(8):1920-1927. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewis C, Roberts NP, Andrew M, Starling E, Bisson JI. Psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2020;11(1):1729633. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1729633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Griner D, Smith TB. Culturally adapted mental health intervention: a meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2006;43(4):531-548. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arundell LL, Barnett F, Buckman JE, Saunders R, Pilling S. The Effectiveness of Adapted Psychological Interventions for People From Ethnic Minority Groups: A Systematic Review and Conceptual Typology. Clin Psych Rev; 2021:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cunningham JA, Kypri K, McCambridge J. Exploratory randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of a waiting list control design. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):150. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asnaani A, Benhamou K, Kaczkurkin AN, Turk-Karan E, Foa EB. Beyond the constraints of an RCT: naturalistic treatment outcomes for anxiety-related disorders. Behav Ther. 2020;51(3):434-446. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2019.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Howard MC, Hoffman ME. Variable-centered, person-centered, and person-specific approaches: where theory meets the method. Organ Res Methods. 2018;21:846-876. doi: 10.1177/1094428117744021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, et al. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(7):748-751. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murray LK, Dorsey S, Haroz E, et al. A common elements treatment approach for adult mental health problems in low- and middle-income countries. Cogn Behav Pract. 2014;21(2):111-123. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

Data sharing statement