Abstract

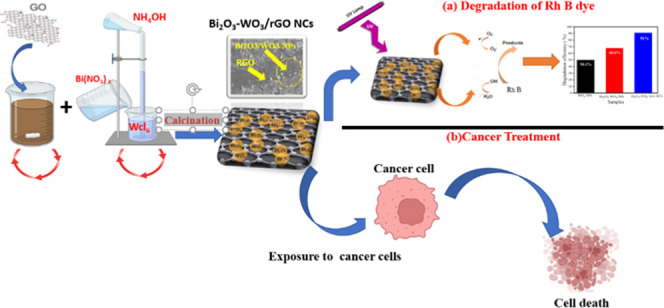

Graphene derivatives and metal oxide-based nanocomposites (NCs) are being studied for their diverse applications including gas sensing, environmental remediation, and biomedicine. The aim of the present work was to evaluate the effect of rGO and Bi2O3 integration on photocatalytic and anticancer efficacy. A novel Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs was successfully prepared via the precipitation method. X-ray crystallography (XRD) data confirmed the crystallographic structure and the phase composition of the prepared samples. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis confirmed the loading of Bi2O3-doped WO3 NPs on rGO sheets. Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) results confirmed that all elements of carbon (C), oxygen (O), tungsten (W), and bismuth (Bi) were present in Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs. The oxidation state and presence of elemental compositions in Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs were verified by the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) study. Raman spectra indicate a reduction in carbon–oxygen functional groups and an increase in the graphitic carbon percentage of the Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs. The functional group present in the prepared samples was examined by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. UV analysis showed that the band gap energy of the synthesized samples was slightly decreased with Bi2O3 and rGO doping. Photoluminescence (PL) spectra showed that the recombination rate of the electron–hole pair decreased with the dopants. Degradation of RhB dye under UV light was employed to evaluate photocatalytic performance. The results showed that the Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs have high photocatalytic activity with a degradation rate of up to 91%. Cytotoxicity studies showed that Bi2O3 and rGO addition enhance the anticancer activity of WO3 against human lung cancer cells (A549) and colorectal cancer cells (HCT116). Moreover, Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs showed improved biocompatibility in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) than pure WO3 NPs. The results of this work showed that Bi2O3-doped WO3 particles decorated on rGO sheets display improved photocatalytic and anticancer activity. The preliminary data warrants further research on such NCs for their applications in the environment and medicine.

1. Introduction

Carbon-based nanomaterials including graphite, graphene, and graphene oxide (GO) have received interest owing to their unique properties and possible applications in electronics, energy storage, and healthcare.1 Specifically, graphene is a two-dimensional (2D) carbonaceous substance with a thin flat sheet of sp2 hybridized carbon atoms in six-membered rings. Its physicochemical properties include strong electrical and thermal conductivities, a large surface area, carrier mobility, chemical stability, optical transmittance, and mechanical strength.2 Due to these excellent properties, graphene has been applied in potential fields, such as optoelectronics, photonics, energy, industry, and environmental remediation.3 However, the poor solubility of graphene in biological media is one of the obstacles to its application in biomedical applications.4,5 To solve this obstacle, graphene oxide (GO) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) have been successfully applied in biomedicine and environmental applications due to their oxygenated functional group.6,7 For example, Mittal et al.6 reported that both GO/rGO exhibited high anticancer activity in A549 cells.

Several different types of metal oxide nanostructures, such as ZnO NPs, TiO2 NPs, and SnO2 NPs, have attracted attention in environmental and biomedical fields due to the unique physicochemical properties and synthesis approaches of these nanomaterials.8,9 Tungsten oxide (WO3) NPs are a common nanomaterial that has a wide range of potential applications because of their band gap (2.4–2.8 eV).10

One of the biggest challenges for investigators focusing on photocatalytic systems and ROS production is developing stable nanomaterials.11 Particularly, two or more metal oxide nanomaterials can be fabricated to enhance the optical properties (band gap energy). At lower band gap energy, the anticancer and photocatalytic activities of nanocomposites (NCs) improved with increasing electrons in the conduction band. Several studies of nanocomposites (NCs) such as WO3-doped TiO2 NCs,12 ZnO-doped TiO2 NCs,13 and Mo-doped WO3 NCs14 have been applied to enhanced photocatalytic performance due to the manipulation of their optical properties. Khalid et al.15 observed that the cytotoxicity of TiO2-doped ZnO nanocomposites (NCs) on HepG2 cells was higher than pure TiO2 NPs and pure ZnO NPs. Due to their unique and tunable physicochemical properties, bismuth oxide (Bi2O3) NPs have also been explored for wastewater treatment and biomedicine.16 Earlier studies reported that Bi2O3 doping in metal oxide NPs plays a role to enhance the photocatalytic activity of metal oxide NPs.17 For instance, Li et al.18 observed that the Bi2O3-doped TiO2 NPs have higher photocatalytic activity in comparison to pure TiO2 NPs. Doping of Bi2O3 affects the band gap energy of WO3 NPs, which increases its visible light absorption and photocatalytic activity.19 Additionally, physicochemical properties such as the structural and optical properties of WO3 NPs are improved by the dopant of Bi2O3 in pure Bi2O3, as shown in this study.20 Khan et al.21 reported that the enhanced photocatalytic activity of the Bi2O3/WO3 NCs under visible light irradiation is greater than those of Bi2O3 and WO3.

Graphene-based nanocomposites have attracted attention for a variety of applications, including gas sensing, energy storage, environmental remediation, and biomedicine.22,23 Presently, several investigators are focusing on fabricating metal oxide nanocomposites (NCs) with GO or rGO nanosheets to improve their optical properties.24 Jo et al.25 reported that the incorporation of graphitic carbon with TiO2 NPs enhanced their photocatalytic activity under UV irradiation compared with pure TiO2 NPs. The TiO2/WO3/GO NCs demonstrate outstanding photocatalytic activity for the degradation of bisphenol under visible light.26 Vu et al.27 revealed that the N, C, S-TiO2-doped WO3/rGO NCs have an extremely high stability level after three cycles. Furthermore, studies on metal oxide-based rGO nanocomposites (NCs) of biological response at the cellular and molecular levels are scarcely studied. For instance, SnO2-ZnO/rGO NCs and Nb-TiO2/rGO NCs exhibited high cytotoxicity on different human cancer cells and enhanced photocatalytic activity.28 Ahamed et al.29 showed that synthesized Mo-ZnO/rGO NCs display higher cytotoxicity on HCT116 and MCF-7 cells than pure ZnO NPs.

The present work aimed to optimize the physicochemical properties of Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs for enhanced photocatalytic and anticancer performance. X-ray crystallography (XRD), field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, UV–vis spectroscopy, Raman scattering, and photoluminescence (PL) spectrometry were carefully used to characterize the synthesized samples. The photocatalytic degradation of synthesized samples against Rhodamine B dye was examined under UV irradiation. The anticancer effects of prepared WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs were assessed against human colorectal cancer (HCT116) and lung cancer (A549) cells. Moreover, the biocompatibility of prepared samples was also evaluated on umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC). The collected results reveal that the Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs exhibit remarkable photocatalytic activity compared with WO3 NPs and Bi2O3 NPs. Assessment of cytotoxicity demonstrates that the dopant of Bi2O3 and rGO enhanced the anticancer efficacy of WO3 NPs against A549 human lung cancer cells and HCT116 colorectal cancer cells. Additionally, the Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs showed enhanced biocompatibility in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) compared to pure WO3 NPs.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. XRD Analysis

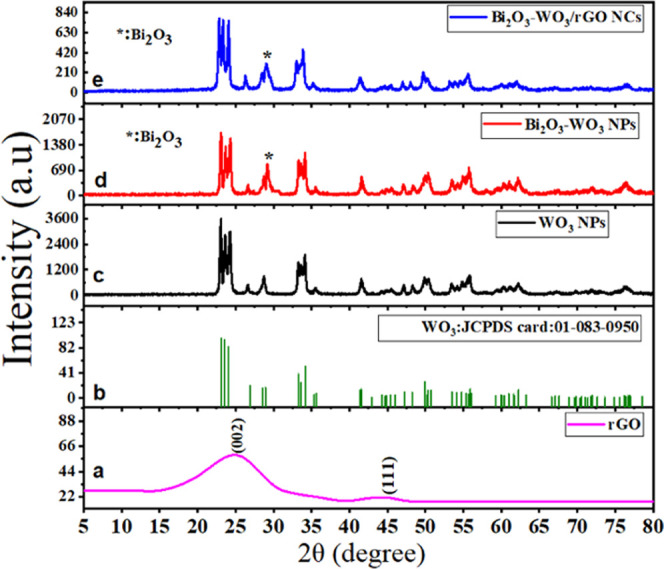

Figure 1a–e shows the XRD spectra of rGO, WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs. XRD spectra of rGO (Figure 1a) show peaks corresponding to the (002) and (111) planes of the graphene lattice, indicating the presence of a high degree of crystallinity. Furthermore, the position of peaks of pure WO3 NPs (Figure 1c) was observed at 2θ values of 23.20, 23.70, 24.37, 26.59, 28. 71, 33.27, 34.13, 35.61, 41.54, 45.47, 48.44, 49.82, 50.56, 53.43, 55.86, 60.21, 62.23, 67.21, 71.87, and 76.43°. These peaks correspond to the (002), (020), (200), (120), (112), (022), (202), (122), (222), (132), (004), (440), (400), (114), (331), (142), (242), (340), (342), (035), and (160) planes of hexagonal WO3 (JCPDS NO: 01-083-0950) (Figure 1b).29 The XRD spectra in Figure 1d,e showed that the position of the peak is slightly shifted to a higher angle. The additional one peak was also observed at 29.12 and 29.23° to the (202) planes of Bi2O3 in prepared Bi2O3-WO3 NPs and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs, respectively, as shown in an earlier study.30 In a comparison of XRD spectra (Figure 1c–e), the intensities of the diffraction peaks of WO3 NPs were decreased with Bi2O3 and rGO doping due to lattice distortion.31 The sharp and high-intensity peaks indicate the high crystallinity nature and purity of the synthesized sample.32 Moreover, the decrease in crystallinity was further confirmed to be due to the rGO dopant in Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs. Debye Scherrer’s formula (1) was used to estimate crystallite size (D).33

| 1 |

where k = 0.90, λ is the wavelength, β is the full width at half-maximum (FWHM), and θ is the reflection angle. Pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs have an average crystal size between 10 and 13 nm. XRD results confirmed the successful synthesis of Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs and the presence of crystalline phases of Bi2O3, WO3, and rGO in the composite material. These results agree with the EDX data (Figure 4) and previous studies.30,34,35

Figure 1.

XRD pattern of rGO (a), pure WO3 NPs (c), the standard pattern of monoclinic WO3 (JCPDS card: 01-083-0950) (b), Bi2O3-WO 3 NPs (d), and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs (e).

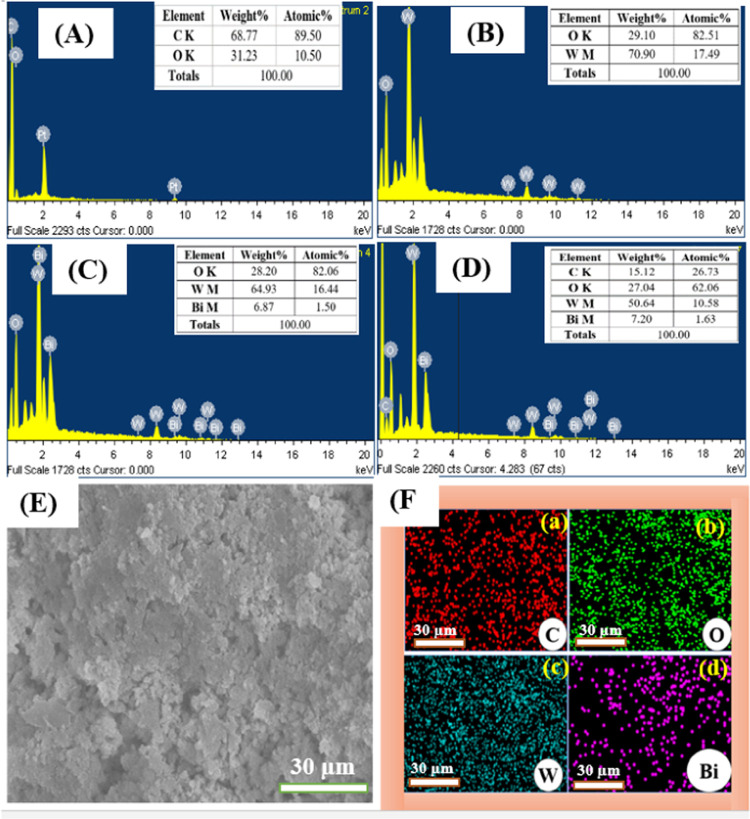

Figure 4.

EDX spectra of rGO (A), pure WO3 NPs (B), Bi2O3-WO3 NPs (C), and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs (D); electron image (E); and SEM elemental mapping of Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs(F): (a) carbon (C), (b) oxygen (O), (c) tungsten (W), and (d) bismuth (Bi).

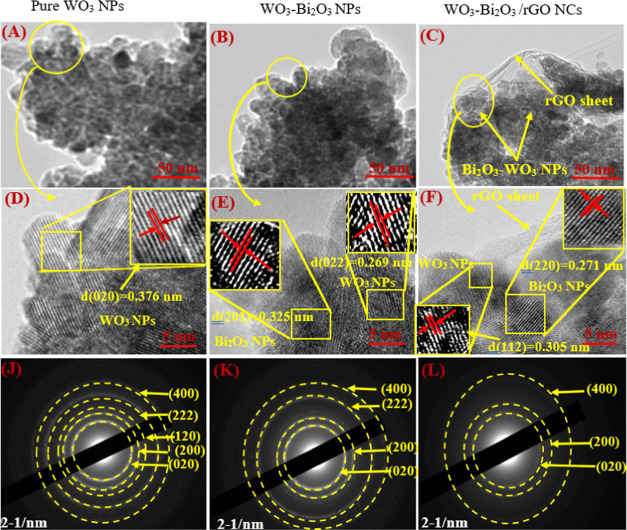

2.2. TEM Analysis

Figure 2A–C shows the low-resolution TEM micrographs, high-resolution (HR)-TEM micrographs, and the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern of synthesized pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs. Figure 2A,B represents the low-resolution TEM images of pure WO3 NPs and Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, respectively. Figure 2C demonstrates that the prepared Bi2O3-WO3 NPs were anchored onto the surface of the rGO sheets. These images confirmed that the Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs were successfully prepared. The HR-TEM images (Figure 2D–F) were recorded to investigate the crystal structure of the prepared samples. The HR-TEM image of Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs (Figure 2F) indicates the presence of Bi2O3 NPs in the WO3 matrix, and Bi2O3-doped WO3 particles successfully imbedded on RGO sheets. The lattice d-spacing of WO3 NPs was 0.376, 0.296, and 0.305 nm for pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs, respectively, in good agreement with (020), (022), and (112) planes from XRD data. Additionally, the distance between two lattice places of Bi2O3 NPs was 0.325 and 0.271 nm to the corresponding (201) and (220) planes, which is in agreement with earlier studies.36,37 SAED patterns confirmed that the pure WO3 NPs (Figure 2J) exhibit well-defined diffraction rings corresponding to the (020), (200), (120), (222), (400), and (022) planes of monoclinic WO3. Moreover, the SAED patterns of Bi2O3-WO3 NPs (Figure 2K) show similar diffraction rings but with some intensity changes due to the presence of Bi2O3 doping. Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs (Figure 2L) exhibited a weaker and broader diffraction ring owing to the influence of rGO on the crystal structure and crystallinity of the NCs.

Figure 2.

(A–C) TEM images, (D–F) HR-TEM images, and (J–L) SAED pattern of prepared samples.

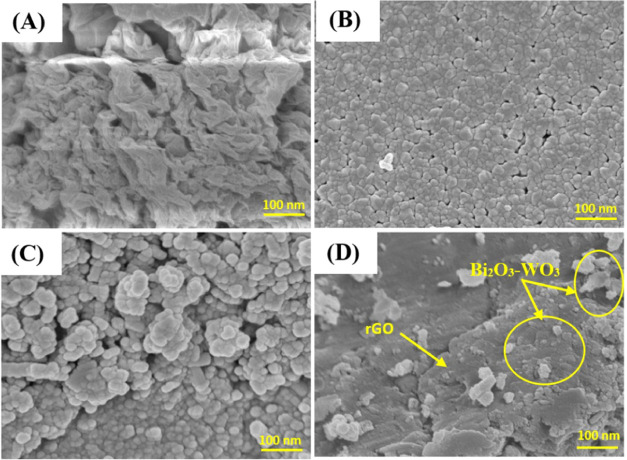

2.3. SEM Analysis

The morphologies of synthesized rGO, pure WO3NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs were further investigated through the FT-SEM technique (Figure 3). Figure 3A shows that the rGO nanosheets have multilayered structures with surface bends and folds due to the matrix sheet of two-dimensional nature. However, these wrinkly surfaces of the rGO nanosheets provide a large specific surface area, which allows rGO composite synthesis with WO3 NPs.38 It can be seen in Figure 3B,C that pure WO3 NPs and Bi2O3-WO3 NPs have a spherical shape and a uniform distribution. These images confirmed that the pure WO3NPs and Bi2O3-WO3 NPs have similar morphosis. Figure 2D illustrates the SEM image of Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs, which confirms that rGO has been successfully doped in Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs. Our findings were also consistent with earlier studies.32,38,39

Figure 3.

FE-SEM images of rGO (A); WO3 NPs (B); Bi2O3-WO3 NPs (C); and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs (D).

2.4. EDX Analysis

The purity and chemical composition of rGO, pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs were further confirmed through EDX analysis. The EDX spectra of all of the prepared samples are shown in Figure 4A–D. Results revealed that all elements of carbon (C), oxygen (O), tungsten (W), and bismuth (Bi) are present in Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs. The homogeneous distribution of C, O, W, and Bi elements in the Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs was examined by SEM elemental mapping (Figure 4F(a–d)). The tables in Figure 4A–D provide a summary of the element analysis in the synthesized samples. These results are supported by XRD data (Figure 1).

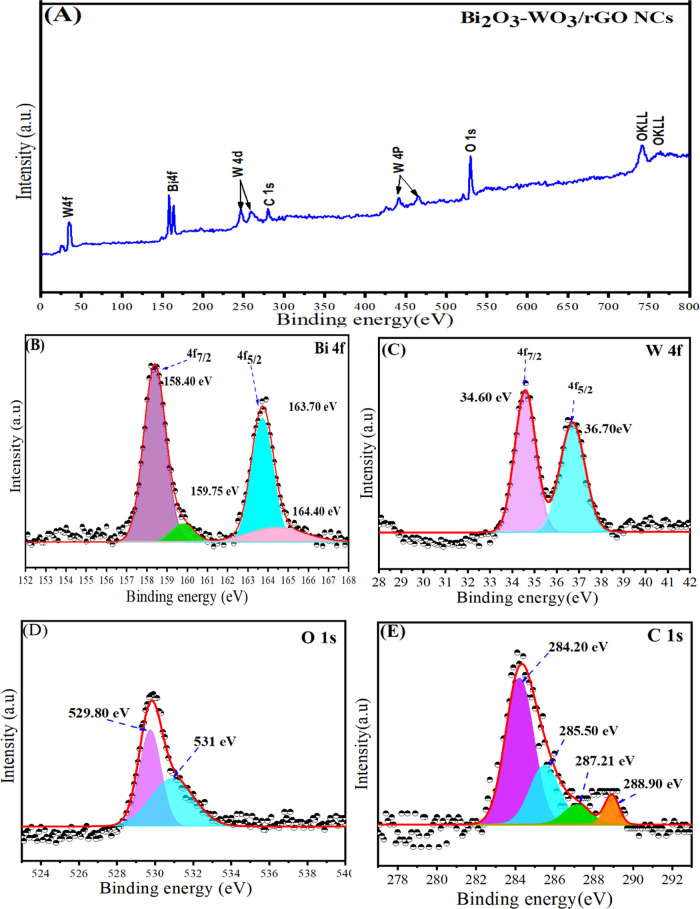

2.5. XPS Analysis

The surface composition and electronic states of the prepared Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs were successfully investigated by using XPS analysis (Figure 5). The reference of the C 1s peak (set at 284.20 eV) was further used to calibrate all of the binding energies obtained for the samples. The presence of elements Bi, W, O, and C without any impurity was confirmed in the full-wide XPS spectra in the obtained Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs (Figure 5A). Figure 4B shows the Bi 4f core-level spectra with two main peaks, which are located at 163.70 eV (Bi 4f5/2) and 158.40 eV (Bi 4f7/2) with a peak separation of 5.3 eV, which are in good agreement with previous studies.40,41 The high-resolution W 4f spectra shown in Figure 5C have two peaks, which have binding energy values of 36.70 and 34.60 eV for W 4f5/2 and W 4f7/2, respectively. These values indicate that the Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs are in the W(VI) oxidation state.42 It can be seen in Figure 5D that the O 1s peaks are located at 529.80 and 531 eV and correspond very well with the oxygen species found in the synthesized Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs. The peak at 529.80 eV indicates a strong interaction between Bi2O3 and WO3 with rGO, while the peak at 531 eV is attributed to defects. The high-resolution spectra of C 1s in Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs can be observed in Figure 5E. The binding energies of C 1s peaks are located at 284.20, 285.50, 287.21, and 288.90 eV, which correspond to the C=C and C–O, and O–C=O bands in Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs, respectively. Our XPS results indicate that rGO is well incorporated into Bi2O3-WO3 NPs.

Figure 5.

(A) XPS spectra of Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs, (B) high-resolution XPS of Bi 4f, (C) high-resolution XPS of W 4f, (D) high-resolution XPS of O 1s, and (E) high-resolution XPS of C 1s of Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs.

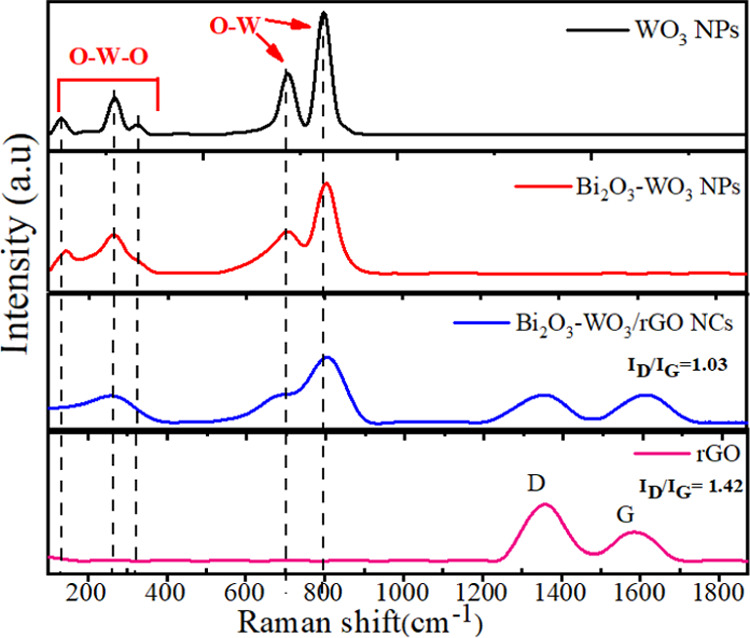

2.6. Raman Analysis

Raman spectroscopy is a nondestructive and fast technique, which was used to characterize graph-based nanocomposites (NCs). Figure 6 shows the Raman spectra of rGO, pure WO3NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs. The Raman spectra of rGO demonstrate two main peaks that are located at 1355 and 1585 cm–1. These peaks are related to the well-known D and G bands that can be shown in graphitic materials, respectively.43 It can be shown that the intensity ratio (ID/IG) of the D and G bands was decreased in Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs compared to rGO. This effect indicates that the graphene oxide (GO) coverts to reduced graphene oxide (rGO). Moreover, the Raman spectra of pure WO3 NPs (Figure 6) exhibit five peaks, which are observed approximately at 130, 274, 330, 710, and 807 cm–1. The peaks assigned at 710 and 810 cm–1 are attributed to the stretching of W–O–W bands, while the peaks at 274 and 330 cm–1 are due to the stretching of O–W–O.44 Furthermore, the peaks of the Raman spectra of Bi2O3-WO3 NPs (Figure 6) are assigned at 130, 274, 710, and 810 cm–1, respectively. For Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs, the peaks of the Raman spectra (Figure 6) are further observed at 274, 710, and 810 cm–1. The Raman spectra exhibited a considerable intensity decrease with a slight shift toward the high wavelength. The shift indicates composite synthesis, although quenching is generally shown in Bi2O3-WO3 NPs and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs.30 Our results are in excellent agreement with the FTIR results (Figure 7) and earlier previous investigations.45,46

Figure 6.

Raman spectra of rGO, pure WO3NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs.

Figure 7.

FT-IR spectra of rGO, pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3 /rGO NCs.

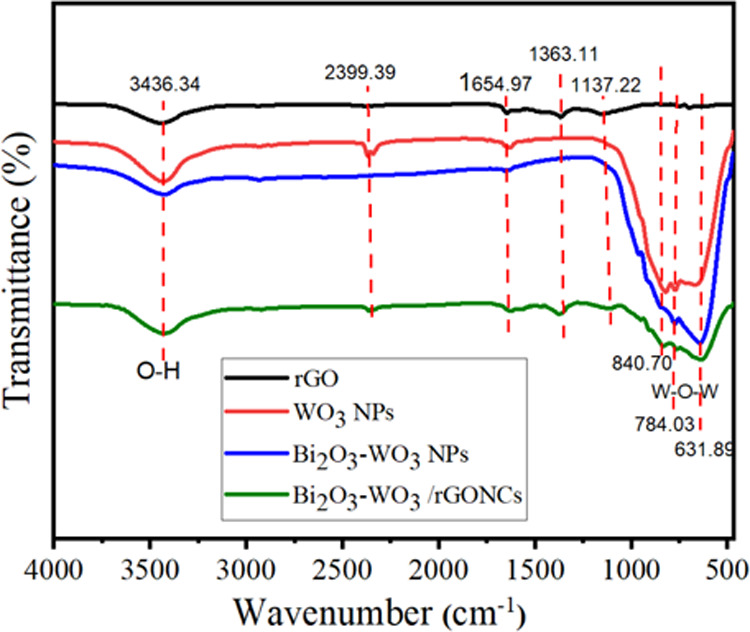

2.7. FT-IR Analysis

FT-IR analysis was employed to study functional groups and changes in chemical composition in the synthesized samples. As depicted in Figure 7, the FT-IR absorption peak of all prepared samples at 3436.34 cm–1 is due to the presence of the O–H group of water.47 The appearance of the bands at 1654.94 cm–1 indicates N–O stretching, which is due to the presence of ammonia solution in the synthesis (Figure 7). The carboxyl (C–OH) group is assigned at 1363.11 cm–1. Peaks at 1137.22 cm–1 indicate C–O stretching vibrations, which are in agreement with this study.38 In addition, the absorption bands at low frequencies (below 1000 cm–1) in pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3 NCs/rGO NCs are attributed to the W–O–W vibration of crystalline WO3.48 These bands are not observed in the rGO nanosheet. These absorption bands show the amount of water and oxygen functional groups in graphite during the oxidation reaction. Our results confirmed that the Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs were successfully prepared, as supported by a previous study.39

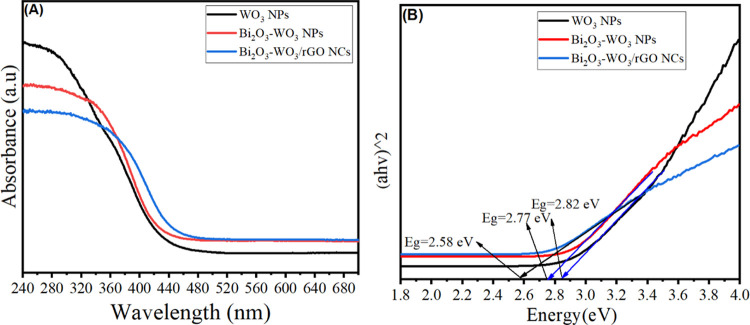

2.8. UV–vis Analysis

The optical properties of synthesized samples were examined by UV–vis spectroscopy. Figure 8A shows the UV absorption of pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs. The absorption edge of pure WO3 NPs can be observed to be around 440 nm. It can be seen that the absorption edge of WO3 NPs was increased after Bi2O3 and rGO doping. However, the Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs illustrate higher UV light absorption abilities compared to pure and Bi2O3-WO3 NPs. The energy of the band gap was calculated using Tauc’s formula (Figure 8B), which is known as relation (2).49

| 2 |

Figure 8.

UV–vis spectra of pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NCs, and Bi2O3-WO3 /rGO NCs (A) and Tauc’s plot for the optical band gap calculations of prepared samples (B).

where n is the absorption coefficient, B is a constant that is often referred to as the band tailing parameter, hv is the photon energy, and Eg is the optical band gap energy. Figure 8B reveals that the band gap energy (Eg) of pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs was 2.82, 2.77, and 2.58 eV, respectively, which were reported by an earlier study.39 Results confirmed that Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs have more efficiency than Bi2O3-WO3 NPs to improve the UV light activity of WO3 NPs. Because of their lower band gap energy, which increases UV light absorption, they can be employed in the photocatalytic degradation of pollutants.50−52

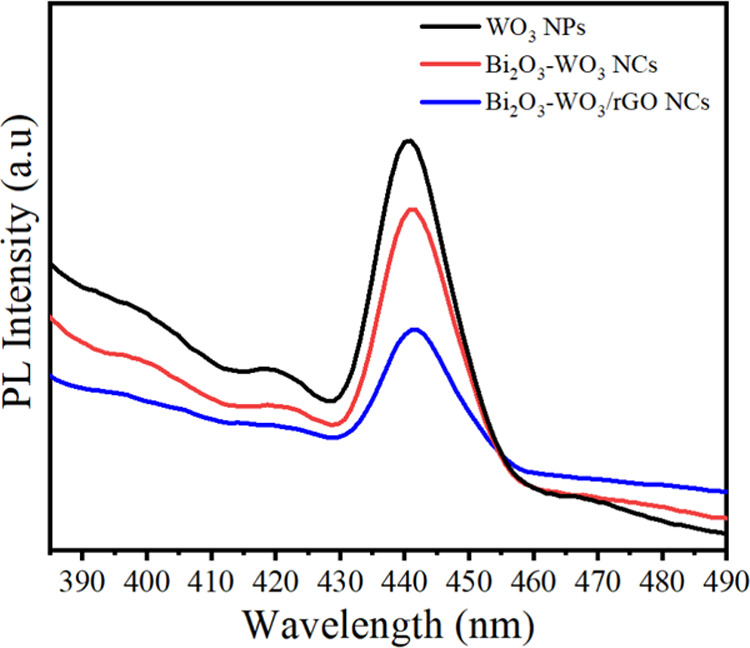

2.9. PL Analysis

Figure 9 illustrates the PL spectra of WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs at an excitation wavelength of 330 nm. The PL spectra of synthesized samples exhibit a broad emission band centered around 441 nm, which is attributed to the oxygen vacancy-related defect states.53Figure 9 shows that the PL intensities of the prepared nanocomposites were decreased with Bi2O3 and rGO dopants compared to pure WO3 NPs. This effect indicated that the recombination rate of electron–hole pairs was reduced in Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs compared with pure WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3 NPs owing to the effective separation of charges (e–/h+). Results suggested that the presence of rGO enhanced charge carrier generation and recombination processes in the prepared samples, which can have applied photocatalytic activity and biomedical applications.39,54 This phenomenon indicated that the rate of recombination was reduced when doping with Bi2O3 and rGO owing to the effective separation of charges (e–/h+).

Figure 9.

PL spectra of WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3- WO3/rGO NCs.

2.10. Anticancer Performance and Cytocompatibility Study

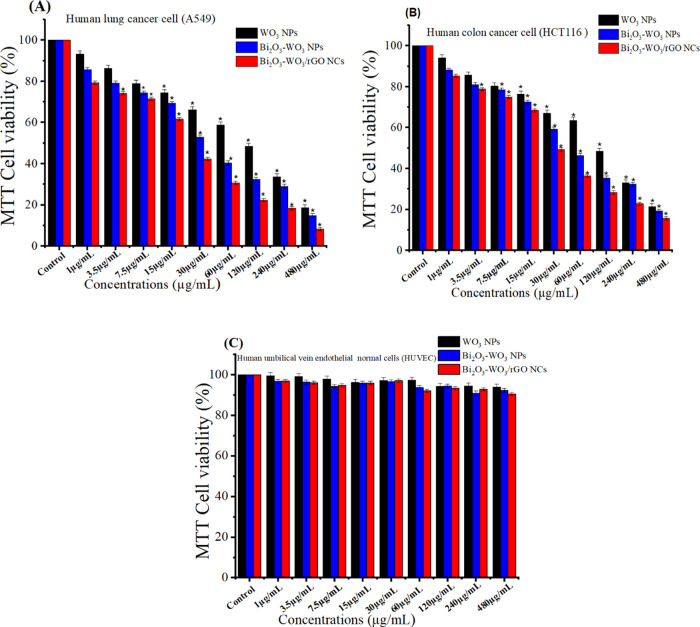

Metal-doped WO3 nanostructures have been widely employed in biomedicine and cancer treatment owing to their excellent physicochemical properties.55−57 In the present work, the anticancer activity of pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs was further examined against human lung (A549) and colorectal (HCT116) cancer cell along with a normal cell line (HUVEC). Different levels of cytotoxicity of all of the synthesized samples at various concentrations (1, 3.5, 7.5, 15, 30, 60.5, 120, 240, 480 μg/mL) in the various cell lines are presented in Figure 10. The results indicate that prepared samples (pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs) have potential as anticancer agents toward human lung A549, and colorectal HCT116 cancer cell lines. Among them, Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs exhibited the highest anticancer activity against the cancer cells (A549 and HCT116), which could be attributed to the synergistic effect of Bi2O3, WO3, and rGO. The results showed that all three types of prepared samples exhibited relatively very low cytotoxicity toward HUVECs (Figure 10C). The cytotoxicity of the nanomaterials toward HUVECs was found to be dose-dependent and increased with increasing concentration. The IC50 values of pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs are presented in Table 1. However, further studies are necessary to evaluate in vivo efficacy and safety profiles before they can be considered for clinical applications.

Figure 10.

MTT assay after 24 h of incubation with prepared samples. (A) A549 cell line and (B) HCT116 cells. Cells were plated in 96-well plates and left overnight. Then, the concentrations (1–480 μg/mL) were added, and after 24 h, a standard MTT test was performed. (C) Compatibility of pure and prepared samples in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVEC).

Table 1. IC50 Values of Synthesized Samples in Cancer Cell Lines (A549 Cells and HCT116 Cells).

| synthesized samples | cancer

cells lines |

|

|---|---|---|

| A549 cells (μg/mL) | HCT116 cells (μg/mL) | |

| WO3 NPs | 76.98 | 86.91 |

| Bi2O3-WO3 NCs | 35.95 | 51.27 |

| Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs | 20.11 | 32.43 |

The MTT assay was used to investigate the cytotoxicity or anticancer activity of the prepared samples. A possible mechanism of anticancer activity of synthesized samples might be through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS are free oxygen radicals that can kill cancer cells through oxidative damage to cellular macromolecules such as DNA. For instance, the synthesized SnO2-ZnO/RGO NCs induced oxidative stress and disrupted the mitochondrial membrane potential of cancer cells, leading to cell death.28

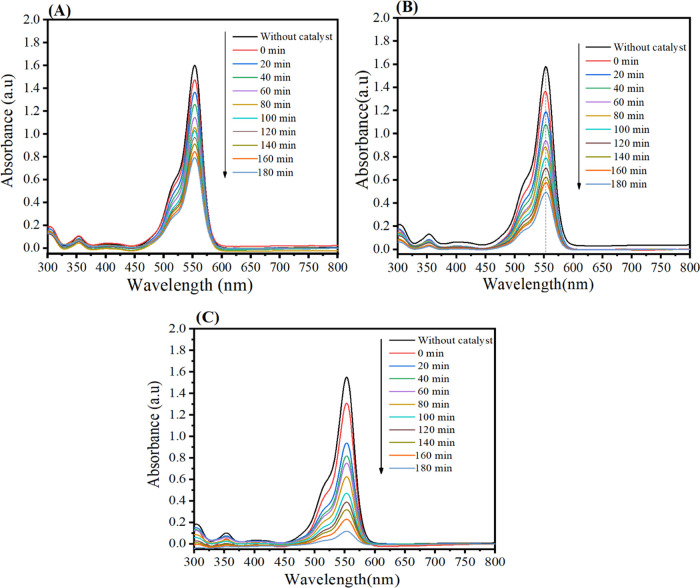

2.11. Photocatalytic Activity

Rhodamine B (Rh B) dye degradation was utilized to evaluate the photocatalytic activity of the as-prepared samples under UV light. Figure 11A–C shows that RhB absorption of WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs at 553 nm reduces every 20 min, and the Rh B dye solution becomes colorless after 180 min. The intensity of absorption peaks of RhB solutions around 553 nm was used to evaluate the photocatalytic activity of the synthesized samples under UV light. It can be seen in Figure 11A–C that the intensity of RhB absorption at 553 nm decreases every 20 min, and the blue Rh B dye solution turns colorless after 180 min.

Figure 11.

UV light absorbance of Rh B solutions as a function of irradiation time: (A) Pure WO3 NPs, (B) Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, (C) Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs.

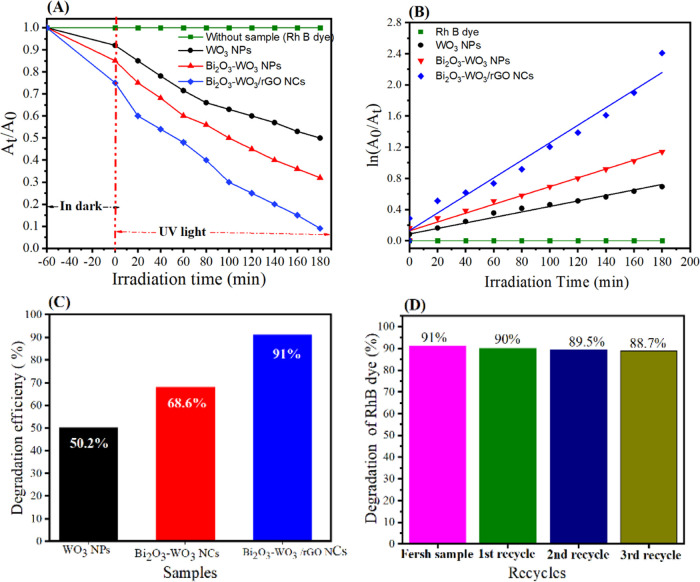

The degradation of RhB under UV light by pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs is shown in Figure 12A. Pseudo-first-order kinetics eq 3 was further used to describe the degradation of RhB (Figure 12B) by the prepared samples under UV irradiation during 180 min, which is typically given by

| 3 |

Figure 12.

(A) Effect of irradiation time (min) on photocatalytic degradation of RhB onto prepared samples for 180 min, (B) first-order photodegradation kinetics, (C) cycling degradation percentage for prepared samples, and (D) cycling degradation curve for Bi2O3-WO3 /rGO NCs.

where the initial absorbance of RhB is denoted by A0, the absorbance of RhB at time t is denoted by At, and the rate constant is denoted by k. Figure 10B shows that the rate constant (k) for WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs was 1, 99 × 10–3, 3.133 × 10–3, and 6.25 × 10–3 min–1, respectively. Figure 12C depicts the degradation efficiency of RhB with pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs under UV irradiation. The degradation efficiencies of 50.2, 68.6, and 91.0% for Rh B dye at 180 min (Figure 12C) were achieved using pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs, respectively. Results indicated that the photocatalytic activity of Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs was greater than that of pure WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3 NPs. This suggested that the photocatalytic activity of the Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs was enhanced due to rGO doping. The reusability of the photocatalyst was investigated by recycling the Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs four times for the degradation of RhB dye with the same conditions. Thus, the improved UV photocatalytic performance of Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs is due to enhanced charge separation and transfer through several paths, as shown in Figure 12. The comparison between prepared Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs and different catalysts in RhB dye is shown in Table 2. These results demonstrated that dopant rGO in Bi2O3-WO3 NPs has the ability to influence charge separation as well as carrier recombination/migration.

Table 2. Comparison of Prepared Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs with Some Reported Samples in the Degradation of Rhodamine B (RhB) Dye.

| sample used | conc. and amount of sample | UV light source | irradiation time (min) | D (%) | references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bi2O3/WO3 NCs/rGO NC | 10 ppm, 35 mg | 400 W (Xenon lamp) | 180 | 91 | present work |

| WO3/Ag/CN NCs | 10 ppm, 10 mg | 400 W (Xenon lamp) | 140 | 96.2 | (58) |

| TiO2@SiO2/WO3/GO NCs | 10 ppm, 25 mg | 500 W (Xenon lamp) | 50 | 98 | (59) |

| TiO2-Ag2O/rGO NCs | 10 ppm, 35 mg | 350 W (Xenon lamp) | 60 | 92 | (60) |

| MoS2/Bi2O2CO3 NCs | 10 ppm, 50 mg | 500 W (Mercury lamp) | 150 | 92 | (61) |

| WO3/TNTs NCs | 10 ppm, 40 mg | 400 W (Xenon lamp) | 60 | 91.8 | (62) |

| Ag/β-Ag2WO4/WO3 NCs | 10 ppm, 30 mg | 350 W (Xenon lamp) | 25 | 99.6 | (63) |

| MoO3-Bi2O3/rGO NC | 10 ppm, 40 mg | 300 W (Xenon lamp) | 120 | 80 | (64) |

2.11.1. Stability

In this investigation, the same Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs were used to degrade RhB dye under UV irradiation to evaluate the stability and recycling potential of photocatalysts. Without any additional processing, the produced Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs were recycled four times by centrifugation under the same conditions. Figure 12D depicts four cycles of RhB degradation. RhB degradation percentages were 91% for a fresh sample, 90% for the first cycle, 89.5% for the second cycle, and 88.7% for the third cycle of Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs. With just a minor drop in degradation efficiency after each cycle, these numbers suggested that the photocatalytic activity of the Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs was stable. These data (Figure 12D) demonstrate the stability of the produced samples during deterioration. Based on our findings, Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs may be useful in biomedicine as well as in environmental cleanup.

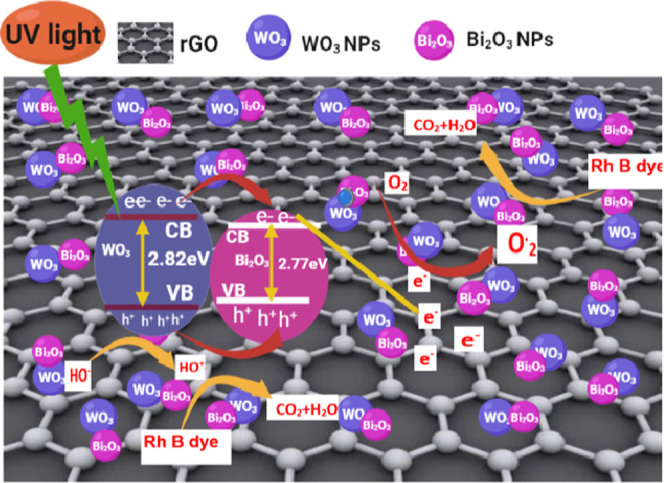

2.11.2. Possible Photocatalytic Mechanism

The possible photocatalytic mechanism of the Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs is shown in Figure 13. The RhB dye degradation involves a chain of chemical reactions that generate free radicals, including superoxide and hydroxyl. Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs and RhB dye were irradiated with UV light. Furthermore, irradiating WO3 NPs generated electron–hole pairs in the valance band (VB) and conduction band (CB) (eq 4). The created electrons in the VB are moved to the CV (Figure 13). According to researchers, electrons are transported from the conduction band (CB) of WO3 to the CB of Bi2O3 due to their closeness (eq 5).65 Therefore, the electrons moved to the conduction band (CB) of Bi2O3 are immediately transferred to the rGO. These electrons can react with oxygen molecules (O2) in water to create superoxide radicals (O2•), which combine with water molecules to degrade RhB dye (eqs 6 and 7). At the same time, the remaining holes in WO3 absorb H2O and hydroxyl radicals (HO–), which causes the production of hydroxyl radicals (HO•) (eq 8). Moreover, they can be decomposed into smaller molecules by these free oxygen radicals (eq 8). Furthermore, the degradation of RhB dye into smaller molecules (eq 9) was carried out by these free oxygen radicals. Results demonstrate that rGO reduced electron–hole pair recombination in Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs, increasing degradation efficiency.

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

Figure 13.

Possible photocatalytic mechanism scheme of the Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs under UV irradiation.

3. Conclusions

A novel Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NC was successfully prepared by the precipitation route. XRD, TEM, SEM, EDX, XPS, Raman, FT-IR, and UV–vis techniques were used to characterize the prepared samples. XRD confirmed the crystallographic structure and phase composition of the prepared samples. TEM and SEM images displayed that Bi2O3-WO3 NPs were tightly anchored on rGO sheets. EDX analysis indicated that carbon (C), oxygen (O), tungsten (W), and bismuth (Bi) were present in Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs. Elemental composition was further supported by XPS. A reduction in carbon–oxygen functional groups and an increase in the graphitic carbon percentage of the Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs were further investigated by Raman spectroscopy. The band gap energy of the pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs was 2.82, 2.77, and 2.58 eV, respectively. PL spectra demonstrated that the rate of electron–hole recombination has been significantly decreased in Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs following Bi2O3 and rGO doping. The degradation efficiency of the prepared pure WO3NPs, Bi2O3-WO3NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs was 50.2, 68.6, and 91%, respectively. Cytotoxicity data showed that Bi2O3 and rGO doping enhances the anticancer activity of WO3 in human lung (A549) and colorectal (HCT116) cancer cells. Moreover, the addition of Bi2O3 and rGO improves the biocompatibility of WO3 in normal human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). This study highlights the importance of Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs in biomedicine and wastewater treatment.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Reagents and Cells

Pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs were successfully synthesized using the following reagents: tungsten chloride (WCl6), bismuth nitrate (Bi (NO3)3:6H2O), graphene oxide, rhodamine B (RhB) dye, and 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Millipore-Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri). An ammonium solution (NH4OH), nitric acid, and hydrazine hydrate (N2H4·H2O) were purchased from Chemical Co., Ltd., China. All of the reagents were of analytical grade, and they were used without any additional purification. Human lung cancer (A549), colorectal cancer (HCT116), and human umbilical vein endothelial (HUVEC) cell lines were acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (ATTC, Manassas, West Virginia).

4.2. Synthesis of Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO)

Reduced graphene oxide (rGO) was synthesized by using hydrazine hydrate as a reducing agent. 600 mg of graphene oxide (GO) was dissolved in 200 mL of distilled water. And 2 mL of hydrazine hydrate (N2H4·H2O) was slowly added to the above solution. Then, the mixture solution was heated to 80 °C and stirred for 3 h. During this process, hydrazine acts as a reducing agent by removing the oxygen-containing groups from the GO and reducing it to rGO. Next, the rGO was washed multiple times with distilled water and ethanol and centrifuged to eliminate any remaining hydrazine and impurities.

4.3. Synthesis of Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs

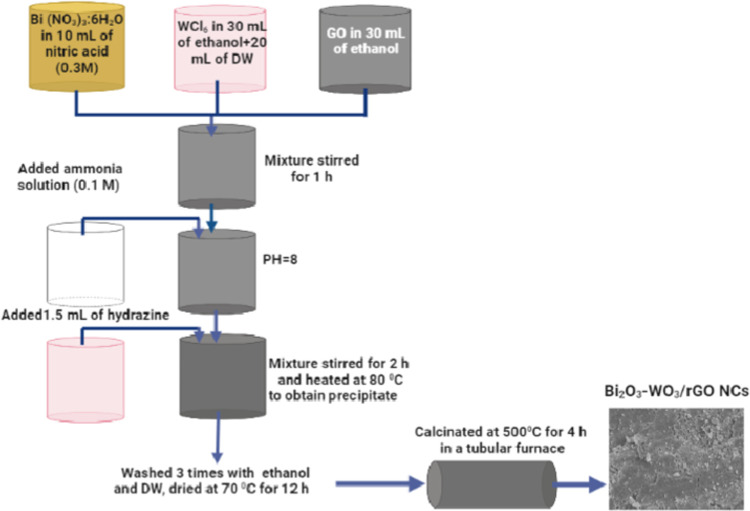

The modified precipitation synthesis was successfully used to synthesize pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs.66 First, three solutions were prepared to fabricate Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs. Then, 1.682 g of tungsten chloride (WCl6) was dissolved in 30 mL of ethanol, and 20 mL of distilled water was added as the first solution. The second solution was produced by dispersing 2.6 mg of bismuth nitrate (Bi(NO3)3:6H2O) into 10 mL of nitric acid (0.3 M). And 20 mg of graphene oxide (GO) was dissolved in 20 mL of ethanol under an ultrasonicator for 30 min as the third solution. The first and second solutions were mixed and sonicated for 20 min. After that, the third solution of GO was added dropwise under continuous stirring for 1 h to obtain a homogeneous solution. Then, 150 mL of ammonia solution (0.1 M) was also added dropwise at room temperature under stirring in 250 mL of the beaker to reach pH 8. Next, 1.5 mL of hydrazine solution was added to the obtained mixture to reduce the graphene oxide (rGO). The mixture solution was continuously stirred for 2 h. On the hotplate, the reaction solution was heated to 80 °C to get the precipitate of the reaction. To eliminate any unreacted ions, this precipitate was dried in an oven set to 70 °C for 12 h and then washed four times with ethanol and distilled water. Finally, the dried powder was calcinated at 500 °C for 5 h in nitrogen gas in a tubular furnace to get Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs. In a similar procedure, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs were prepared without mixing GO. Pure WO3 NPs were also synthesized by a similar procedure, without the addition of bismuth nitrate (Bi(NO3)3:6H2O) and GO. The protocol for the synthesis of Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs is shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1. Synthesis Procedure of Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs.

4.4. Characterization

The crystal structure and crystalline phase of prepared samples were investigated by recording XRD patterns (PanAnalytic X’Pert Pro, Malvern Instruments, UK) with Cu Kα radiation (=0.15405 nm, at 45 kV and 40 mA). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to study the morphologies of the synthesized samples. The chemical elements and states of the prepared samples were examined by EDX and XPS, respectively. Raman spectra were recorded using the WITec alpha 300RA Raman Confocal Microscope. A Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (PerkinElmer Paragon 500) recorded the group function of the obtained samples at the wavenumber range of 500–4000 cm–1. A UV–visible spectrophotometer (Hitachi U-2600) and a fluorescence spectrometer (Hitachi F-4600) were used to analyze the optical properties of the prepared samples.

4.5. Cell Culture

Human lung cancer (A549), colorectal cancer (HCT116), and a normal cell line (HUVEC) were used in the present work as in vitro models. A549 and HCT116 cancer cells were acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (ATTC) (Manassas, Virginia). Therefore, the cells were grown in a flask in full medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (100 μg/mL streptomycin and 100 U/mL penicillin) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The culture media was changed every 2–3 days. The cells were subcultured when they reached 90% confluence.

4.6. Cell Exposure and Anticancer Assay

The synthesized samples (1 mg/mL) were further dissolved in a culture medium (DMEM) and sonicated for 20 min to prepare a stock suspension solution. Different concentrations (1, 3.5, 7.5, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240, 480 μg/mL) of each obtained sample were prepared through serial dilution from a stock solution under ultrasonication for 30 min. Cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a cell density of 20 000 cells/mL and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 24 h. Next, these cells were exposed to different concentrations of each prepared sample and maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 24 h. The MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-4,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay was used to evaluate the anticancer activity of samples. After 24 h, 100 μL of MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL dissolved in DMEM without FBS) was added to each well with an incubator for 3 h. Then, 100 μL of DMSO was further added to dissolve formazan crystals formed by the viable cells in each well. A microplate reader was used to get an accurate reading of the optical density (OD) at 570 nm.

4.7. Evaluation of Photocatalytic Activity

The photocatalytic activity of synthesized samples was measured by RhB dye degradation under UV irradiation (time: between 11:30 am and 2:30 pm, date: October–November 2022, place: KSU, KSA). 10 mg/L (10 ppm) of RhB dye was dissolved in 100 mL of distilled water. The source of UV light used in this experiment was a 400 W xenon lamp (CEL-HXF300) with a wavelength (<420 nm). Then, 2 mL of Rh B solution was taken before adding the samples. After that, 35 mg of the prepared samples (pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3-WO3 NPs, and Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs) was added to RhB aqueous solution (10 ppm) as suspension solution. Before UV irradiation, the mixture solution with the synthesized samples was stirred in a dark place for 60 min to achieve an adsorption–desorption equilibrium process. Every 20 min, 2 mL of suspension solution was taken and centrifuged to separate the sample. Afterward, the absorption of the centrifuged solution was further measured using a Shimadzu UV-2450 spectrophotometer. The degradation of RhB dye was calculated using eq 10.

| 10 |

where A0 is the initial absorbance before exposure to UV light and At is the absorbance throughout the irradiation. In this study, Bi2O3-WO3/rGO NCs were selected to evaluate their cycle stability.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Biological activity data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Dennett’s multiple comparison tests. We compared treated and untreated groups using this strategy. p-value (P < 0.05) indicated statistical significance.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere appreciation to researchers supporting project number (RSPD2023R813), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for funding this research.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Lalwani G.; D’Agati M.; Khan A. M.; Sitharaman B. Toxicology of Graphene-Based Nanomaterials. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2016, 105, 109–144. 10.1016/j.addr.2016.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W.; Deng X.; Huang W.; Qing X.; Shao Z. The Physicochemical Properties of Graphene Nanocomposites Influence the Anticancer Effect. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 7254534 10.1155/2019/7254534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariq W.; Ali F.; Arslan C.; Nasir A.; Gillani S. H.; Rehman A. Synthesis and Applications of Graphene and Graphene-Based Nanocomposites: Conventional to Artificial Intelligence Approaches. Front. Environ. Chem. 2022, 3, 890408 10.3389/FENVC.2022.890408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.; Wei P.; Zhou Z.; Wei T. Interactions of Graphene with Mammalian Cells: Molecular Mechanisms and Biomedical Insights. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2016, 105, 145–162. 10.1016/j.addr.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan D.; Kim F.; Luo J.; Cruz-Silva R.; Cote L. J.; Jang H. D.; Huang J. Energetic Graphene Oxide: Challenges and Opportunities. Nano Today 2012, 7, 137–152. 10.1016/j.nantod.2012.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal S.; Kumar V.; Dhiman N.; Chauhan L. K.; Pasricha R.; Pandey A. K. Physico-Chemical Properties Based Differential Toxicity of Graphene Oxide/Reduced Graphene Oxide in Human Lung Cells Mediated through Oxidative Stress. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39548 10.1038/srep39548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcano D. C.; Kosynkin D. V.; Berlin J. M.; Sinitskii A.; Sun Z.; Slesarev A.; Alemany L. B.; Lu W.; Tour J. M. Improved Synthesis of Graphene Oxide. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 4806–4814. 10.1021/NN1006368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherif S.; Djelal H.; Firmin S.; Bonnet P.; Frezet L.; Kane A.; Assadi A. A.; Trari M.; Yazid H. The Impact of Material Design on the Photocatalytic Removal Efficiency and Toxicity of Two Textile Dyes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 66640–66658. 10.1007/S11356-022-20452-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandvakili A.; Moradi M.; Ashoo P.; Pournejati R.; Yosefi R.; Karbalaei-Heidari H. R.; Behaein S. Investigating Cytotoxicity Effect of Ag-Deposited, Doped and Coated Titanium Dioxide Nanotubes on Breast Cancer Cells. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 32, 103915 10.1016/J.MTCOMM.2022.103915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhri A.; Behrouz S. Photocatalytic Properties of Tungsten Trioxide (WO3) Nanoparticles for Degradation of Lidocaine under Visible and Sunlight Irradiation. Sol. Energy 2015, 112, 163–168. 10.1016/j.solener.2014.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Shi W. Recent Developments in Visible-Light Photocatalytic Degradation of Antibiotics. Chin. J. Catal. 2016, 37, 792–799. 10.1016/S1872-2067(15)61054-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DohL·eviL·-MitroviL· Z.; StojadinoviL· S.; Lozzi L.; AškrabiL· S.; RosiL· M.; TomiL· N.; PaunoviL· N.; LazoviL· S.; NikoliL· M. G.; Santucci S. WO3/TiO2 Composite Coatings: Structural, Optical and Photocatalytic Properties. Mater. Res. Bull. 2016, 83, 217–224. 10.1016/J.MATERRESBULL.2016.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay G. K.; Rajput J. K.; Pathak T. K.; Kumar V.; Purohit L. P. Synthesis of ZnO: TiO2 Nanocomposites for Photocatalyst Application in Visible Light. Vacuum 2019, 160, 154–163. 10.1016/J.VACUUM.2018.11.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song X. C.; Yang E.; Liu G.; Zhang Y.; Liu Z. S.; Chen H. F.; Wang Y. Preparation and Photocatalytic Activity of Mo-Doped WO3 Nanowires. J. Nanopart. Res. 2010, 12, 2813–2819. 10.1007/s11051-010-9859-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khalid A. D.; Ur-Rehman N.; Tariq G. H.; Ullah S.; Buzdar S. A.; Iqbal S. S.; Sher E. K.; Alsaiari N. S.; Hickman G. J.; Sher F. Functional Bioinspired Nanocomposites for Anticancer Activity with Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species. Chemosphere 2023, 310, 136885 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala-Ayala M. T.; Ferrer-Pacheco M. Y.; Muñoz-Saldaña J. Manufacturing of Photoactive β-Bismuth Oxide by Flame Spray Oxidation. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2021, 30, 1107–1119. 10.1007/s11666-021-01182-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X.; Huang X.; Huang Y.; Feng Q.; Chen W.; Ju C.; Du Y.; Bai T.; Wang D. Crystal Phase Transition of β-Bi2O3 and Its Enhanced Photocatalytic Activities for Tetracycline Hydrochloride. Colloids Surf., A 2021, 626, 127068 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2021.127068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.; Cai J.; Wu X.; Zheng F.; Lin X.; Liang W.; Chen J.; Zheng J.; Lai Z.; Chen T.; Zhu L. Fabrication of Positively and Negatively Charged, Double-Shelled, Nanostructured Hollow Spheres for Photodegradation of Cationic and Anionic Aromatic Pollutants under Sunlight Irradiation. Appl. Catal., B 2014, 160, 279–285. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2014.05.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari S. P.; Dean H.; Hood Z. D.; Peng R.; More K. L.; Ivanov I.; Wu Z.; Lachgar A. Visible-Light-Driven Bi2O3/WO3 Composites with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 91094–91102. 10.1039/C5RA13579F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Afolalu S. A.; Soetan S. B.; Ongbali S. O.; Abioye A. A.; Oni A. S.. Morphological Characterization and Physio-Chemical Properties of Nanoparticle - Review. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing, 2019; Vol. 640012065 10.1088/1757-899X/640/1/012065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan I.; Abdalla A.; Qurashi A. Synthesis of Hierarchical WO3 and Bi2O3/WO3 Nanocomposite for Solar-Driven Water Splitting Applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 3431–3439. 10.1016/J.IJHYDENE.2016.11.105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niknam Z.; Hosseinzadeh F.; Shams F.; Fath-Bayati L.; Nuoroozi G.; Amirabad L. M.; Mohebichamkhorami F.; Naeimi S. K.; Ghafouri-Fard S.; Zali H.; Tayebi L.; Rasmi Y. Recent Advances and Challenges in Graphene-Based Nanocomposite Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering Application. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2022, 110, 1695–1721. 10.1002/jbm.a.37417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. E.; Mohammad A.; Ali W.; Imran M.; Bashiri A. H.; Zakri W.. Properties of Metal and Metal Oxides Nanocomposites. In Nanocomposites-Advanced Materials for Energy and Environmental Aspects; Woodhead Publishing, 2023; pp 23–39 10.1016/B978-0-323-99704-1.00027-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakarrao N.; Rao T. S.; Lakshmi K. V. D.; Divya G.; Jaishree G.; Raju I. M.; Alim S. A. Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance of Nb Doped TiO2/Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites over Rhodamine B Dye under Visible Light Illumination. Sustainable Environ. Res. 2021, 31, 37 10.1186/s42834-021-00110-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jo W. K.; Won Y.; Hwang I.; Tayade R. J. Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Aqueous Nitrobenzene Using Graphitic Carbon-TiO2 Composites. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 3455–3461. 10.1021/ie500245d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hao X.; Li M.; Zhang L.; Wang K.; Liu C. Photocatalyst TiO2/WO3/GO Nano-Composite with High Efficient Photocatalytic Performance for BPA Degradation under Visible Light and Solar Light Illumination. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017, 55, 140–148. 10.1016/J.JIEC.2017.06.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vu T. P. T.; Tran D. T.; Dang V. C. Novel N,C,S-TiO2/WO3/RGO Z-Scheme Heterojunction with Enhanced Visible-Light Driven Photocatalytic Performance. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 610, 49–60. 10.1016/J.JCIS.2021.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahamed M.; Akhtar M. J.; Khan M. A. Ma.; Alhadlaq H. A. SnO2-Doped ZnO/Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites: Synthesis, Characterization, and Improved Anticancer Activity via Oxidative Stress Pathway. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 89–104. 10.2147/IJN.S285392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahamed M.; Akhtar M. J.; Khan M. A. M.; Alhadlaq H. A. Enhanced Anticancer Performance of Eco-Friendly-Prepared Mo-ZnO/RGO Nanocomposites: Role of Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 7103–7115. 10.1021/acsomega.1c06789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan I.; Abdalla A.; Qurashi A. Synthesis of Hierarchical WO3 and Bi2O3/WO3 Nanocomposite for Solar-Driven Water Splitting Applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 3431–3439. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.11.105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hung C. M.; Dat D. Q.; Van Duy N.; Van Quang V.; Van Toan N.; Van Hieu N.; Hoa N. D. Facile Synthesis of Ultrafine RGO/WO3 Nanowire Nanocomposites for Highly Sensitive Toxic NH3 Gas Sensors. Mater. Res. Bull. 2020, 125, 110810 10.1016/j.materresbull.2020.110810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng F.; Wang S.; Yu W.; Huang T.; Sun Y.; Cheng C.; Chen X.; Hao J.; Dai N. Ultrasensitive Ppb-Level H2S Gas Sensor at Room Temperature Based on WO3/RGO Hybrids. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 5008–5016. 10.1007/s10854-020-03067-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muniz F. T. L.; Miranda M. A. R.; Morilla Dos Santos C.; Sasaki J. M. The Scherrer Equation and the Dynamical Theory of X-Ray Diffraction. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Adv. 2016, 72, 385–390. 10.1107/S205327331600365X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeevitha G.; Abhinayaa R.; Mangalaraj D.; Ponpandian N.; Meena P.; Mounasamy V.; Madanagurusamy S. Porous Reduced Graphene Oxide (RGO)/WO3 Nanocomposites for the Enhanced Detection of NH3 at Room Temperature. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 1799–1811. 10.1039/c9na00048h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z.; Chen W.; Jin L.; Cui F.; Song Z.; Zhu C. High-Performance Acetylene Sensor with Heterostructure Based on WO3 Nanolamellae/Reduced Graphene Oxide (RGO) Nanosheets Operating at Low Temperature. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 909 10.3390/nano8110909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M.; Ding Y.; Zhang H.; Ren J.; Li J.; Wan C.; Hong Y.; Qi M.; Mei B.; Deng L.; Wu Y.; Han T.; Zhang H.; Liu J. A Novel Ultrathin Single-Crystalline Bi2O3 Nanosheet Wrapped by Reduced Graphene Oxide with Improved Electron Transfer for Li Storage. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2020, 24, 2487–2497. 10.1007/s10008-020-04788-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan W.; Nie Y.; Wu Z.; Li J.; Ding Y.; Ma C.; Chen D. Novel Rare Earth Ions Doped Bi2WO6/RGO Hybrids Assisted by Ionic Liquid with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity under Natural Sunlight. J. Sol–Gel Sci. Technol. 2021, 98, 84–94. 10.1007/s10971-021-05494-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Punetha D.; Pandey S. K. Sensitivity Enhancement of Ammonia Gas Sensor Based on Hydrothermally Synthesized RGO/WO3 Nanocomposites. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 1738–1745. 10.1109/JSEN.2019.2950781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J.; Jiang T.; Han Y.; Okoth O. K.; Cheng L.; Zhang J. Construction of Dual Z-Scheme Bi2S3/Bi2O3/WO3 Ternary Film with Enhanced Visible Light Photoelectrocatalytic Performance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 144632 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.144632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shinde N. M.; Xia Q. X.; Yun J. M.; Singh S.; Mane R. S.; Kim K. H. A Binder-Free Wet Chemical Synthesis Approach to Decorate Nanoflowers of Bismuth Oxide on Ni-Foam for Fabricating Laboratory Scale Potential Pencil-Type Asymmetric Supercapacitor Device. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 6601–6611. 10.1039/c7dt00953d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S.; Sahoo R. K.; Shinde N. M.; Yun J. M.; Mane R. S.; Kim K. H. Synthesis of Bi2O3-MnO2 Nanocomposite Electrode for Wide-Potential Window High-Performance Supercapacitor. Energies 2019, 12, 3320 10.3390/en12173320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.; Sun H.; Guo Y.; Wang D.; Sun D.; Su Q.; Ding S.; Du G.; Xu B. Synthesis of Oxygen Vacancies Implanted Ultrathin WO3-x Nanorods/Reduced Graphene Oxide Anode with Outstanding Li-Ion Storage. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 7573–7586. 10.1007/s10853-020-05747-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur J.; Anand K.; Anand K.; Thangaraj R.; Singh R. C. Synthesis, Characterization and Photocatalytic Activity of Visible-Light-Driven Reduced Graphene Oxide–CeO2 Nanocomposite. Indian J. Phys. 2016, 90, 1183–1194. 10.1007/s12648-016-0861-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H.; Mali M. G.; Kim M. W.; Al-Deyab S. S.; Yoon S. S. Electrostatic Spray Deposition of Transparent Tungsten Oxide Thin-Film Photoanodes for Solar Water Splitting. Catal. Today 2016, 260, 89–94. 10.1016/j.cattod.2015.03.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur J.; Anand K.; Anand K.; Singh R. C. WO3 Nanolamellae/Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites for Highly Sensitive and Selective Acetone Sensing. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 12894–12907. 10.1007/s10853-018-2558-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sumathi M.; Prakasam A.; Anbarasan P. M. High Capable Visible Light Driven Photocatalytic Activity of WO3 /g-C3 N4 Hetrostructure Catalysts Synthesized by a Novel One Step Microwave Irradiation Route. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 3294–3304. 10.1007/s10854-018-00602-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R.; Sharma M.; Goswamy J. K. Synthesis and Characterization of WO3–SnO2/RGO Nanocomposite for Propan-2-Ol Sensing. Sensors Int. 2022, 3, 100172 10.1016/j.sintl.2022.100172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Q.; Liu T.; Liu J.; Liu Q.; Jing X.; Zhang H.; Huang G.; Wang J. Controllable Synthesis and Enhanced Gas Sensing Properties of a Single-Crystalline WO3-RGO Porous Nanocomposite. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 14192–14199. 10.1039/c6ra28379a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis E. A.; Mott N. F. Conduction in Non-Crystalline Systems V. Conductivity, Optical Absorption and Photoconductivity in Amorphous Semiconductors. Philos. Mag. 1970, 22, 903–922. 10.1080/14786437008221061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tran V. A.; Nguyen T. P.; Le V. T.; Kim I. T.; Lee S. W.; Nguyen C. T. Excellent Photocatalytic Activity of Ternary Ag@WO3@rGO Nanocomposites under Solar Simulation Irradiation. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2021, 6, 108–117. 10.1016/j.jsamd.2020.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AbuMousa R. A.; Baig U.; Gondal M. A.; AlSalhi M. S.; Alqahtani F. Y.; Akhtar S.; Aleanizy F. S.; Dastageer M. A. Photo-Catalytic Killing of HeLa Cancer Cells Using Facile Synthesized Pure and Ag Loaded WO3 Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15224 10.1038/s41598-018-33434-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channei D.; Chansaenpak K.; Phanichphant S.; Jannoey P.; Khanitchaidecha W.; Nakaruk A. Synthesis and Characterization of WO3/CeO2Heterostructured Nanoparticles for Photodegradation of Indigo Carmine Dye. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 19771–19777. 10.1021/acsomega.1c02453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong J.; Zhang T.; Qiu F.; Rong X.; Zhu X.; Zhang X. Preparation of Hierarchical Micro/Nanostructured Bi2S3-WO3composites for Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 685, 812–819. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.06.210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Lee P. S.; Ma J. Synthesis, Growth Mechanism and Room-Temperature Blue Luminescence Emission of Uniform WO3 Nanosheets with W as Starting Material. J. Cryst. Growth 2009, 311, 316–319. 10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2008.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han B.; Popov A. L.; Shekunova T. O.; Kozlov D. A.; Ivanova O. S.; Rumyantsev A. A.; Shcherbakov A. B.; Popova N. R.; Baranchikov A. E.; Ivanov V. K. Highly Crystalline WO3 Nanoparticles Are Nontoxic to Stem Cells and Cancer Cells. J. Nanomater. 2019, 2019, 5384132 10.1155/2019/5384132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood F.; Iqbal J.; Jan T.; Ahmed W.; Ahmed W.; Arshad A.; Mansoor Q.; Ilyas S. Z.; Ismail M.; Ahmad I. Effect of Sn Doping on the Structural, Optical, Electrical and Anticancer Properties of WO3 Nanoplates. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 14334–14341. 10.1016/J.CERAMINT.2016.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood F.; Iqbal J.; Ismail M.; Mehmood A. Ni Doped WO3 Nanoplates: An Excellent Photocatalyst and Novel Nanomaterial for Enhanced Anticancer Activities. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 746, 729–738. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.01.409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.; Xiao X.; Wang Y.; Ye Z. Ag Nanoparticles Decorated WO3 /g-C3 N4 2D/2D Heterostructure with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity for Organic Pollutants Degradation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 467, 1000–1010. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.10.236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.; Liu X.; Long H.; Ding F.; Liu Q.; Chen X. Preparation and Photocatalytic Performance of Graphene Oxide/WO 3 Quantum Dots/TiO2 @SiO2 Microspheres. Vacuum 2019, 164, 66–71. 10.1016/j.vacuum.2019.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H.; Wang T. Graphene Oxide (RGO)-Metal Oxide (TiO2/Ag2O) Based Nanocomposites for the Removal of Rhodamine B at UV–Visible Light. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2021, 154, 110100 10.1016/j.jpcs.2021.110100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Yun G.; Bai Y.; An N.; Lian J.; Huang H.; Su B. Photodegradation of Rhodamine B with MoS2 /Bi2O2 CO 3 Composites under UV Light Irradiation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 313, 537–544. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.06.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao M. W.; Wang L. S.; Huang X. J.; Wu Y. D.; Dang Z. Synthesis and Characterization of WO3/Titanate Nanotubes Nanocomposite with Enhanced Photocatalytic Properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 470, 486–491. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2008.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q.; Yao J.; Arif M.; Huang T.; Liu X.; Duan G.; Yang X. Facile Fabrication and Photocatalytic Performance of WO3 Nanoplates in Situ Decorated with Ag/β-Ag2WO4 Nanoparticles. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 1969–1978. 10.1016/j.jece.2018.02.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Govea R.; Orona-Návar C.; Lugo-Bueno S. F.; Hernández N.; Mahlknecht J.; Garciá-Garciá A.; Ornelas-Soto N. Bi2O3/RGO/MonO3n-1all-Solid-State Ternary Z-Scheme for Visible-Light Driven Photocatalytic Degradation of Bisphenol A and Acetaminophen in Groundwater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104170 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S.; Sharma R.; Sharma V.; Harith G.; Sivakumar V.; Krishnan V. Role of RGO Support and Irradiation Source on the Photocatalytic Activity of CdS-ZnO Semiconductor Nanostructures. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2016, 7, 1684–1697. 10.3762/bjnano.7.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi P.; Singh J. P. Visible Light Induced Selective Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2to CH4on In2O3-RGO Nanocomposites. J. CO2 Util. 2021, 43, 101376 10.1016/j.jcou.2020.101376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]