Abstract

Black boys have been dying by suicide at an increasing rate. Although the reasons for this increase are unknown, suicide in Black boys is likely influenced by multiple, intersecting risk factors, including historical and ongoing trauma. Schools can serve as an important mechanism of support for Black boys; however, without intentional anti-racist frameworks that acknowledge how intersecting identities can exacerbate risk for suicide, schools can overlook opportunities for care and perpetuate a cycle of racism that compromises the mental health of Black youth. By recognizing their own implicit biases, modeling anti-racist practices, listening to and recognizing the strengths and diversity of Black youth, and fostering school-family-community partnerships, school psychologists can help transform the school environment to be a safe and culturally affirming place for Black youth. This paper outlines how school psychologists can apply a trauma- and Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (JEDI)-informed approach to suicide prevention in order to more holistically support Black boys, disrupt patterns of aggressive disciplinary procedures, and improve school-based suicide prevention programs. By applying this lens across a multitiered systems of support (MTSS) framework, school psychologists can help to prevent the deaths of Black boys and begin to prioritize the lives of Black boys.

Keywords: Suicide, Mental Health Services, Prevention, Social Justice, Trauma, Violence, School and Community

The innocent country set you down in a ghetto in which, in fact, it intended that you should perish. Let me spell out precisely what I mean by that, for the heart of the matter is here, and the root of my dispute with my country. You were born where you were born and faced the future that you faced because you were black and for no other reason. The limits of your ambition were, thus, expected to be set forever. You were born into a society which spelled out with brutal clarity, and in as many ways as possible, that you were a worthless human being. You were not expected to aspire to excellence: you were expected to make peace with mediocrity.

– James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time

Introduction

As James Baldwin wrote to his nephew in 1963, Black boys are born into a society that intends for them to “perish” (Baldwin, 1993). And, in fact, the rate of suicide among Black boys1 has shown an alarming increase over the past few decades (Bridge et al., 2015; Lindsey et al., 2019; Sheftall et al., 2016). Yet, discourse on suicide prevention is primarily framed around non-Latinx White (NLW) culture (Marraccini et al., 2021a; Opara et al., 2020), rendering suicidality in Black youth “invisible” (Bath & Njoroge, 2020; p. 19). Processes of gender and racial socialization interact to produce different commonalities in mental health experiences and access to supports for each racial-gendered identity (e.g., Black boys, non-binary individuals). Black boys face unique threats to accessing wellness (Howard et al., 2013; Mizell, 1999) as a result of intersecting internal and external processes (Prilleltensky, 2008). Internal, psychological processes include one’s own understanding and relationship with identity, culture, needs, and expectations (e.g., internalized rejection of emotionality as weakness, acceptance of substance use as an acceptable way of coping with distress; Prilleltensky, 2008). External, environmental processes involve how one is perceived and treated by others (e.g., racist treatment by healthcare providers in medical settings, police in the community, and teachers in schools; Howard et al., 2013; Prilleltensky, 2008). Thus, in addition to the many pathways conferring risk for suicide in all youth, in Black Americans, the impact of systemic, structural, interpersonal, and internalized racism is a key driver of negative health outcomes (Bath & Njoroge, 2020; Lambert et al., 2009) including suicidal ideation (Assari et al., 2017a; Opara et al., 2020).

Although schools have been conceptualized as a “great equalizer” for social, ecological, and health outcomes (Growe & Montgomery, 2003), their governing policies and psychological practices, together, can threaten Black boys’ wellness (Prilleltensky, 2008). For Black students, structural, interpersonal, and internalized racism permeates school systems and perpetuates negative educational and health outcomes (Benner et al., 2018). Behaviors that go against non-Latinx White (NLW) normativity (e.g., emotional outbursts, heighted responses to stimuli, and disengagement in the classroom) can be misidentified by school personnel as “problem behaviors” such as apathy or defiance (Dutil, 2020; Crosby et al., 2018). Psychological symptoms of depression, anxiety, or trauma in Black boys can present as “problem behaviors” (e.g., aggression, defiance) and misinterpreted as reasons for discipline. These misunderstandings can exacerbate aggressive disciplinary procedures that land Black boys in juvenile detention centers where they are significantly less likely to receive mental health care (Barksdale et al., 2010) and, instead, become victims of the school-to-prison pipeline (Congressional Black Caucus, 2019; Noguera, 2016). These actions not only compromise opportunities for providing Black boys with care, they can also exacerbate symptoms related to mental health conditions.

This paper explores how school practices intersect with psychological risk factors to prevent or exacerbate suicide risk in Black boys,2 and identifies strategies towards prevention. Concepts informing school-based suicide prevention for Black boys are presented in four main sections that address: (1) a theoretical framework for understanding suicide risk in Black boys; (2) the historical and current sociopolitical context of being a Black boy in the US; (3) research related to suicide-related thoughts and behaviors in Black boys; and (4) implications for practice.

We first present a theoretical framework for understanding suicide risk in Black boys, which accounts for historical and ongoing racial trauma. Next, we provide a historical overview of the role of schools in perpetuating racism and oppression of Black boys and describe the current sociopolitical context, in which we present school-based practices that are shaping Black student development, as well as some of the obstructions and facilitators to mental health care faced by Black families. Following these overviews, we share current research pertaining to prevalence of suicide-related behaviors, as well as risk and protective factors of suicide, in Black boys. We conclude by linking this research to school psychology practice implications, describing current models of suicide prevention and explicitly calling for a trauma- and justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (JEDI)- informed approach to disrupt these negative patterns in schools. Specific recommendations are aimed at: (a) creating a positive and safe school environment for Black boys; and (b) tailoring school-based suicide prevention practices to acknowledge and account for the historical and ongoing trauma faced by Black boys, including how the intersection of trauma, psychological processes, and school environment may influence risk.

Theoretical Framework for Understanding Suicide Risk

Suicide stems from multiple, converging factors, such as biological, environmental, and psychological factors (AFSP, 2021). Theoretical frameworks for understanding suicide risk have begun to distinguish risk for suicidal ideation (thoughts) and suicide attempts (behaviors), to better elucidate specific drivers leading to an attempt (Klonsky et al., 2018). These theories, identified as “ideation-to-action” frameworks, have been described by multiple researchers (e.g., Klonsky et al., 2018; Van Orden et al., 2010). One of the most commonly studied of these models, Joiner’s Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide (IPTS), proposes that suicidal ideation stems from a sense of hopelessness about feelings of disconnect (i.e., thwarted belongingness) and perceived burdensomeness, with diminished fear of death and higher levels of pain tolerance increasing the likelihood for an individual to make a suicide attempt (Van Orden et al., 2010).

Although IPTS is predominantly based on NLW normative culture and research, Opara and colleagues (2020) recently presented an adapted model of IPTS that integrates an intersectional framework and bioecological model for understanding suicidal behaviors for Black children. This model places interacting systems, including systemic oppression, racism, and marginalization, as risk factors for suicide among Black children, who may also experience psychological factors of IPTS (burdensomeness, thwarted belonginess, hopelessness), within a broader bioecological system (e.g., society, community, school, immediate environment; Opara et al., 2020). Other theoretical frameworks for understanding suicide risk in Black Americans have also underscored the need to consider systems level drivers of suicide risk in Black youth, including the race-related experiences of Black youth in school settings (Marraccini et al., 2021a; Wong et al., 2014). Collectively, researchers have called for clinicians, in and out of schools, to attend to the historical and ongoing trauma, abuse, and oppression of Black individuals that intersect with presenting symptoms and concerns for risk (Bath & Njoroge, 2020; Marraccini et al., 2021a; Opara et al., 2020).

Historical and Current Sociopolitical Context

Prilleltensky and Gonick (1996) name political and psychological oppression as separate but interlocking forces in which political oppression relates to “material, legal, military, economic, and/or other social barriers to the fulfilment of self-determination, distributive justice, and democratic participation” (p. 130). Psychological oppression is “the internalized view of self as negative, and as not deserving more resources or increased participation in societal affairs, resulting from the use of affective, behavioral, cognitive, material, linguistic, and cultural mechanisms by agents of domination to affirm their own political superiority” (Prilleltensky & Gonick, 1996, p. 130). Both work in tandem to deny Black students’ and families’ access to wellness at the individual, relational, and collective domains (Prilleltensky, 2008). Whereas psychological oppression gives rise to mental health conditions that can lead to suicidality, it cannot be examined separately from the political oppression that infiltrates and is upheld in schools and throughout society. For Black students, families, and communities, mental health must be examined in the context of a political system that enslaved their ancestors and an education system that actively excluded them until 1954. In fact, disparate outcomes for Black students in the American education system are as old, if not older, than public education itself.

Historical Context

A modern understanding of history starts with the Brown vs. Board of Education (1954) lawsuit that led education toward a {misguided} focus on individual characteristics rather than the interlocking systemic effects that produce negative outcomes for Black students (i.e., systematic racism). Systemic racism “encompasses the racial stereotyping, prejudices, and emotions of Whites, as well as the discriminatory practices and racialized institutions engineered to produce long-term domination of African American and other people of color” (Feagin & Barnett, 2004, p. 1102). A visible example of systematic racism in schools includes the curriculums and teaching strategies that are specifically designed to benefit White students, while taking a colorblind lens to issues such as racism and oppression (Kohli et al., 2017). Without challenging systematic racism in schools and society, a focus on the individual characteristics of Black students can be harmful, reinforcing the misguided notion that Black students should be able to “pull themselves up by their bootstraps,” despite being in an environment that is designed to knock them down. A present-day example includes the idea of “grit.” The notion that by teaching Black youth to have “grit” schools can help Black youth “overcome adversity” and reduce disparities, has been widely accepted in education policy and practice, obfuscating the detrimental effects of systemic racism (Love, 2019; Tefera et al., 2019).

The federally funded Equality of Educational Opportunity Report (Coleman, 1966), known as the “Coleman Report,” was also highly influential with both researchers and policymakers (Wong & Nicotera, 2004). Though challenged on methodological grounds and in the documented lived experiences of Black students, two findings from this report shaped approaches to closing opportunity gaps (then identified as “achievement gaps”) between Black and NLW students. First, school resources (e.g., school facilities, curriculum, and teacher quality) did not show statistically significant effects on student achievement; and second, the most significant effect on student achievement was the background characteristics of other students, or peer effects (Coleman, 1966; 1990). These findings, along with the ethos of the Brown vs. Board decision and the publication of A Nation at Risk (United States, 1983), which made strong claims about the decline of American global competitiveness, shifted thinking from equalizing educational inputs to equalizing outputs – without attention to disparate inputs that face Black students.

The No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act (2001), coming roughly fifty years after Brown vs. Board, solidified the same movement under the visage of high stakes accountability systems. One positive outgrowth of this movement, however, was that the role of the educator and other school-based personnel was an essential element of NCLB accountability policies. Indeed, a new resurgence in research demonstrated that for Black students, Black educators and school-based personnel do matter for Black students (Gershenson et al., 2021). For example, helping students apply critical consciousness, defined as “the ability to recognize and analyze systems of inequality and the commitment to take action against these systems,” can facilitate a pathway towards academic engagement and motivation in Black youth (El-Amin et al., 2017; p. 18). Findings solidified the importance of diversifying the educator workforce (by increasing the number of Black school-based personnel) and training all educators to better serve Black students by overcoming implicit and explicit biases and practices that are embedded within the fabric of the school (Gershenson et al., 2021). Yet, integration of schools effectively erased Black schools and dismissed Black teachers from the profession, interrupting processes of education, cultural socialization, and development of critical consciousness for Black youth (Tillman, 2004). Resulting outcomes likely contributed to the current racialized disparate school practices toward Black youth, highlighting the importance of JEDI practices in spite of historical events that likely obstructed identity development and school success.

Current Sociopolitical Context

Undoubtedly, these political processes have created school environments that deny Black youth a sense of belonging and community to holistically thrive. Such conditions present direct pathways for Black students to internalize psychological oppression, develop a thwarted sense of belongingness, and feel undeserving of care (Prilleltensky & Gonick, 1996). As relational and collective domains are often tethered to one’s individual sense of wellness, an individual’s positive experience often cannot be fully enjoyed as long as the collective (e.g., all Black youth) have the same opportunities and access to wellness. Therefore, in the following sections we elaborate on the sociopolitical context of school-based services, including disproportionate disciplinary practices and mental health diagnoses, and obstructions and facilitators to care in schools and in school-community systems. Note, however, that this literature reflects only a portion of the day-to-day oppression and inequities faced by Black communities.

Disproportionate Disciplinary and Mental Health Referrals in School

Oppressive tools, such as punitive racist disciplinary practices, a majority-White teacher workforce (with implicit and explicit anti-Black biases), and obstructions to mental health services, threaten the safety and well-being of Black youth and reinforce the school to prison pipeline (Cauce, 2002; Congressional Black Caucus, 2019; Noguera, 2016; Parker et al., 2019). This insidious nature of racism in the discipline process contributes to inequities in student achievement as well – students suspended or expelled are prevented from receiving access to educational instruction, leading to increased school disengagement (Cook et al., 2019). These practices are well-documented, most adversely affecting Black students compared to other racial or ethnic-racial identity groups (Malkus, 2016).

Despite increased attention to exclusionary discipline practices (Morris & Perry, 2016), disproportionality remains, with Black boys making up the largest group of students affected (Girvan, et al., 2017; Skiba & Losen, 2016). A recent meta-analysis indicates that, compared to NLW youth, Black students are more than two and a half times as likely to be disciplined in school (Young et al., 2018). These exclusionary disciplinary practices appear to have bidirectional effects on student mental health – that is, mental health problems may place youth in a more vulnerable position for being disciplined and disciplinary practices may also worsen mental health problems (Ford et al., 2018; Rushton et al., 2002). Yet, findings from a recent systematic review identify the potential for mental health services delivered during early childhood to be effective for promoting behavior management (Albritton et al., 2019). Unfortunately, the application of school based mental health services and consultation for behavioral problems is more likely to be utilized in schools serving predominantly affluent, White students compared to those serving predominantly low-income and ethnic and racial minoritized students, especially Black students (Albritton et al., 2019; Ramey, 2015). Instead, these schools are more likely to implement criminalized disciplinary policies with minoritized youth (e.g., suspensions, referrals to police; Ramey, 2015).

This is especially disconcerting, as more than 75% of students of color in need of mental health services do not receive treatment, especially among urban and Black students (Kataoka et al., 2002). Although school-based programs appear to play a critical role in providing services to Black and other minoritized youth (Cummings & Druss, 2011; Locke et al., 2017), disparities in school-based mental health services for Black youth remain (Barksdale et al., 2010). If students are assessed for mental health concerns, they are more likely to be diagnosed with conduct, behavioral, or learning disorders than NLW youth (Ghandour et al., 2019; Zablotsky & Alford, 2020) and less likely to receive treatment for internalizing symptoms (Katoaka et al., 2002; Shatkin, 2015). These diagnoses are often associated with symptoms seen by educators as “problem behaviors,” leading to punitive practices that reinforce the school-to-prison pipeline (Congressional Black Caucus, 2019; Noguera, 2016; Parker et al., 2019).

Although research dedicated towards understanding how depression, trauma, and suicidal ideation present in Black youth is scant, scholars propose that symptoms of other internalizing disorders may be “masked” as anger or irritability (Clarke & Mosleh, 2015). Instead, symptoms may present as aggressive behaviors that can lead to suspension and expulsion in schools (Assari et al., 2018a; Mallet, 2016). Experiencing violence has been shown to associate with aggressive behavior and depressive symptoms in Black boys (DuRant et al., 1994) and, compared to youth of other racial and ethnic groups, Black boys have demonstrated a higher co-occurrence of symptoms of anxiety, aggression, and depression (McLaughlin et al., 2007). Clinicians may not be aware of how to accurately assess for and identify internalizing symptoms within the cultural context of Black children’s experience, thus, missing a crucial opportunity to provide appropriate services. These missed opportunities may place youth at risk to aggressive disciplinary actions that can land them in juvenile detention centers, further exacerbating their mental health symptoms (Ford et al., 2018; Rushton et al., 2002). As detainees, they are less likely to have access to mental health care (Barksdale et al., 2010) and are at increased risk for dying by suicide (Gallagher & Dobrin, 2006; Hayes, 2009).

Obstructions in Linkages and Access to Mental Health Care

Several perceptual and structural reasons that can disrupt pathways to mental health care for Black individuals have been proposed (Cauce, 2002). Examples include limited access to health insurance, stigmatization of mental health, fear and mistrust of treatment providers, and a lack of culturally sensitive approaches to treatment (Lindsey et al., 2010; Murry et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2007). Obstructions3 extend beyond cultural differences, but also relate to the systematic oppression, institutional inequalities, and structural disparities embedded in systems of care (Burkett, 2017). Case workers have identified Black children as needing counseling services less often than NLW children (Wells et al., 2009) and teachers have indicated high degrees of comfort in recognizing externalizing problems in Black youth, but lower levels in recognizing internalizing problems (Williams et al., 2007). Schools serving predominantly minoritized student bodies appear less likely to have resources and supports for mental health services (Planey et al., 2019; Opara et al., 2020), and Black parents have identified several obstructions to accessing care for their children in schools (e.g., difficulty in navigating the school when seeking help, limited supports/resources; Lindsey et al., 2013; Murry et al., 2011).

Although teachers working in schools serving predominantly Black students have described concerns related to parent disengagement and lack of support, those working in schools with strong school-community partnerships have described parents as supportive (Williams et al., 2007). Such findings suggest the potential for strong school-community-family relationships (involving, for example, neighborhood roundtables, local church connections, and partnerships with community organization volunteers; Williams et al., 2007) to combat against negative bias against Black parents. Established therapeutic relationships and trustworthiness (Lindsey et al., 2006), as well as referrals or mandates by authorities such as teachers or schools (Graves, 2017; Lindsey et al., 2006; Murry et al., 2011), may also help reinforce access to care.

Although we are not aware of studies exploring school referrals for Black youth with suicide risk, research appears mixed regarding differential access to community care in Black youth with such concerns. An early study reported no significant differences in receipt of counseling between NLW and Black youth with suicidal behaviors (Pirkis, 2003). More recent research indicates that, compared to NLW youth, Black youth were less likely to receive mental health care following a suicide-related event and their need for treatment was less strongly associated with treatment engagement than it is for NLW youth (Freedenthal, 2007). Black youth were also less likely to present at the emergency department with psychiatric concerns compared to NLW youth (Pittsenbarger & Mannix, 2014). Collectively, findings showcase how obstructions to care persist even among Black youth with elevated risk for suicide.

Suicide and Suicidal Behaviors

Findings from numerous studies identify increased rates of suicides and suicide attempts in Black youth (Lindsey et al., 2019; Price & Khubchandani, 2019). In 2019, it was estimated that a total of 0.9 per 100,000 Black pre-adolescent (ages 8-12) boys and 7.7 per 100,000 Black adolescent (ages 13-18) boys died by suicide (CDC, n.d.). While suicide rates in NLW pre-adolescent children decreased over the past two decades, they have shown a significant rise in Black pre-adolescent children (Bridge et al., 2015). Moreover, pre-adolescent children who have died by suicide are more commonly Black and male (Bridge et al., 2018; Sheftall et al., 2016), with Black pre-adolescent children significantly more likely to die by hanging, strangulation, or suffocation (considered to be among the most accessible and lethal means of suicide) compared to non-Black children (Sheftall et al., 2016). In contrast, however, recent data (2018-2019) compiled by the CDC show similar rates of suicides classified as death due to suffocation in Black and White boys between ages 12-18 (approximately 40% in each group; CDC, n.d.). Irrespective of the means used for suicide, the increased likelihood for Black decedents to have deaths misclassified, leading to an underreporting of deaths classified as suicides, suggests that these rates are likely underestimates of the actual number of Black youth suicides (Ali et al., 2021).

Data collected by the Youth and Behavior Risk Surveillance Survey (YRBS) from 1991 to 2017 suggest a positive linear trend in self-reported suicide attempts (odds ratio [OR] = 1.04) and suicide attempts leading to injuries (OR = 1.04) among Black adolescent boys (Lindsey et al., 2019). Although the risk for Black boys to die by suicide was significantly higher than for Black girls (Joe et al., 2018), increased rates of suicide attempts over the past two decades were documented in Black adolescent boys and girls, with a 60% and 182% increase from 2001 to 2017, respectively (Price & Khubchandani, 2019). Compared to adolescents, pre-adolescent children hospitalized for suicide-related crises were also more commonly Black and male (Marraccini et al., 2021b).

In contrast to the increased rates of suicides and suicide attempts, suicidal ideation and suicide plans measured from YRBS data over the past three decades have shown a linear decrease across nearly all racial-ethnic and sex groups, including Black adolescent boys (Lindsey et al., 2019). Earlier research also suggests that, compared to NLW and Latinx youth, Black youth were less likely to report thoughts of suicide or a previous suicide attempt (Blum et al., 2000). An exception to these lower rates of suicidal ideation, however, can be found among boys in juvenile detention centers, where findings from at least one study suggest that, although few detainees reported sharing thoughts of death with others, thoughts of death were higher among Black (and Hispanic) detainees compared to NLW detainees (Abram et al., 2008). Taken together, Black boys appear to be increasingly likely to attempt and die by suicide, but, compared to youth of other ethnic-racial backgrounds, less likely to report thoughts or plans of suicide.

Risk and Protective Factors

Despite many overlapping risk and protective factors for NLW and Black children and adolescents (e.g., underlying psychopathology, substance abuse; Joe et al., 2009; 2018), the historical and current sociopolitical context of Black lives necessitates unique considerations for understanding suicide risk in Black youth. Opara and colleagues (2020) reviewed suicide research in Black children and identified four key factors that we summarize here: (1) mental health; (2) economic marginalization; (3) racism and discrimination; and (4) intersectionality. We also present (5) protective factors associated with lower suicide risk in Black youth.

Mental Health

Although underlying mental health conditions remain linked to suicide risk in Black children (e.g. O’Donnell et al., 2004; Spann et al., 2006), concerningly, in one study, nearly half of the sample of Black youth reporting a suicide attempt did not have a diagnosed mental health disorder by the time of their attempt (Joe et al., 2009). This finding is consistent with more recent research (Ali et al., 2021), which suggests that, compared to NLW adolescents, Black and other minoritized adolescents dying from suicide were less likely to have mental health problems or a history of mental health treatment. Black adolescents dying from suicide were found to be significantly less likely to have a documented mental health problem (adjusted OR [aOR] = 0.60), depressed mood (aOR = 0.70), intimate partner problems (aOR = 0.63), and other relationship problems (aOR = 0.64; Ali et al., 2021). In an earlier study, although mental health treatment and somatic symptoms were significant predictors of a suicide attempt in Black girls, they were not significant for Black boys (Borowsky et al., 2001). Findings from other studies have indicated that alcohol and substance use are less frequently identified as precipitants to suicide in Black youth than in NLW youth (Garlow, 2002; Groves et al., 2007). It is unclear if lower rates of mental health problems and treatment relate to improper or culturally insensitive diagnoses, obstructions of use, or other factors (Joe et al., 2009; Opara et al., 2020).

Economic Marginalization

Economic marginalization reflects a direct link between political and psychological oppression, contributing to mental health issues in Black boys. Black children and families are overrepresented within the lowest socioeconomic status (SES) groups, and, compared to NLW individuals, are less likely to graduate from high school and more likely to have lower incomes (Opara et al., 2020). For those living in under-resourced, low-income, and racially segregated conditions, exposure to community violence, gang activity, and drug use, which are closely linked to mental health problems, can further increase suicide risk (O’Donnell et al., 2004; Opara et al., 2020). Although higher SES is often considered a protective factor, it can also place Black youth in a more vulnerable position in terms of social isolation and pressure for success and renders less potent promotive effects for Black individuals compared to NLW individuals (Assari et al., 2018b; 2018c). Subjective perceptions of higher SES have been shown to interact with perceptions of discrimination in Black youth, intensifying effects on depressive symptoms (Assari et al., 2018a). Thus, both high and low SES may confer risk for mental health problems.

Racism and Discrimination

Experiences of ethnic and racial discrimination can interfere with treatment seeking (Goldston et al. 2008) and lead to psychological difficulties, such as increased depressive symptoms, decreased psychological well-being and life satisfaction (English et al., 2014; Lambert et al., 2009; Seaton et al., 2010), and increased risk for suicide-related behaviors (Assari et al., 2017a; Walker et al., 2017). Black boys have reported discrimination at a higher prevalence compared to Black girls4 (Assari et al., 2017a) with worse outcomes over time (Assari et al. 2017b). They also face harsher and more extreme disciplinary practices in school compared to NLW students (Bryan et al., 2012; Wallace et al., 2008; Skiba et al., 2011). Opara and colleagues (2020) described how chronic experiences of racial discrimination can exacerbate the stress responses (Berger & Sarnyai, 2015), which heightens risk for psychopathology and suicidal behavior (Polanco-Roman et al., 2019). Moreover, victimization of violence has been identified as a strong predictor of suicide attempts in Black boys (Borowsky et al., 2001). These empirical findings reinforce the race-based traumatic stress injury theory proposed by Carter (2007), which outlined how racial discrimination, harassment, and aversive-hostility can be experienced as negative, uncontrollable, and long-lasting, potentially leading to symptoms associated with trauma (e.g., hyperactivity, depression, avoidance, and increased vigilance).

Examples of racial discrimination in school may include forms of microaggressions from peers (e.g., social exclusion) and adults (e.g., lower academic expectations by teachers), as well as harsher levels of disciplinary procedures aimed at Black students by school staff and resource officers contributing to the school to prison pipeline (Bleakley & Bleakley, 2018; Morris & Perry, 2016). Black students frequently witness and experience the use of racial slurs, deliberate avoidance by peers, and demeaning unconscious behaviors in schools, which are associated with negative mental health outcomes (Jernigan & Daniel, 2011; Saleem et al., 2020). These experiences are often invalidated by school personnel, contributing to increased feelings of isolation of Black students in schools and oversight of the effects of these traumatic experiences (Jernigan & Daniel, 2011; Saleem et al., 2020). Despite the robust literature documenting the negative academic and psychological effects from these race-related traumas, limited research has explored the effects of in-school racial discrimination or disciplinary procedures on suicide in Black students (Marraccini et al., 2021a). Evidence does suggest, however, that experiences of racial discrimination in school can lessen Black students’ attachment to teachers and educational commitment, leading to increased behavioral problems (Unnever et al., 2016), intimating how racial discrimination in school may influence known protective factors of suicide.

Intersectionality

Black youth are a heterogenous group, with diversity across histories of trauma and oppression, ethnicity, time lived in the U.S., SES, ability, sexual and gender identity, skin color, body size, region, and religion, among other identities and identifiers. Accordingly, a full understanding of suicide risk in Black boys must acknowledge the complexity of these experiences produced by intersectionality (American Psychological Association [APA], 2018). Intersectionality is a frame for understanding how systems of privilege, power and oppression interact to produce different experiences for individuals based on their unique combination of social identities (Crenshaw, 1989; Love, 2019). For example, Queer Black boys not only experience anti-Black racism, but also face homonegativity, and all the specific ways those two forms of oppression interact to create unique stressors for Queer Black boys (Crenshaw, 1989). Indeed, Black and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning (LGBTQ) youth were found to be more susceptible to disciplinary referrals compared to heterosexual students (Poteat et al., 2016). Moreover, LGBTQ identity was associated with higher risk for suicide in Black youth (Mereish et al., 2019) and Black boys specifically (Borowsky et al., 2001), rendering Black youth identifying as LGBTQ particularly vulnerable.

Environmental context can also influence how varying factors confer risk for suicide. Higher SES was found to associate with higher depressive symptoms for Black adolescents living in predominantly White neighborhoods, but not for those living in predominantly Black neighborhoods (Assari et al., 2018c). Findings from a study comparing African American and Caribbean Black adolescents indicated that the former group was approximately four and a half times more likely to report a suicide attempt (Joe et al., 2009), intimating the presence of unique risk factors in Black Americans with a family history of enslavement.

Although much of these findings point to discrimination as a salient risk factor across identities, privilege and oppression in other components of identity influence the nature and magnitude of any given discriminatory experience. Thus, although anti-Black racism may lead to racial trauma symptoms for some Black youth, school and health professionals should be careful not to generalize across all Black individuals. In other words, school professionals should be aware of the ways Black students often face racism at the interpersonal and structural levels, and simultaneously the individuality and uniqueness of every Black student and their experiences.

Protective Factors

The Congressional Black Caucus (2019) identified five categories of strength and resiliency in Black individuals that converge to reinforce a sense of connectedness or mattering that may help to protect against suicide. These include: strong family relationships, closeness, and support; religious and spirituality; community and social support; personal factors (e.g., academics, emotional well-being) and positive racial identity; and environmental factors (e.g., housing, income, employment; Congressional Black Caucus, 2019; Jones & Neblett, 2017).

Of the empirical work that has addressed these protective factors, findings have been inconsistent. For example, findings from multiple studies suggest religiosity may only minimally predict suicidal ideation in Black youth (O’Donnell et al., 2004; Spann et al., 2006) with findings from at least one study failing to support a significant relationship between religiosity and suicidal ideation in Black boys (Cole-Lewis et al., 2016). Similarly, family closeness was found to associate with suicidal ideation in Black youth overall (Matlin et al., 2011; O’Donnell et al., 2004) and in Black girls specifically (Cole-Lewis et al., 2016), but has not been a consistent protective factor when explored specifically in Black boys (Cole-Lewis et al., 2016). School connectedness and attachment appear to play a protective role against suicide in students without disaggregating results by race, but have not emerged as consistent predictors of suicide in Black youth (Cole-Lewis et al., 2016; O’Donnell et al., 2004; Marraccini et al., 2021a).

Inconsistent findings across studies may reflect limitations of traditional resilience frameworks for capturing the unique lived experiences of Black youth (APA, 2008). For example, maladaptive coping responses such as hypervigilance and fearlessness may actually be protective for youth who have experienced violence or other trauma in school (Woods-Jaeger et al., 2020). Although these responses have been associated with aggressive behavior (Gaylord-Harden et al., 2017), they can also provide protection in the face of continued threats of violence occurring in and out of school (Woods-Jaeger et al., 2020). Collectively, these findings indicate the need to consider the environmental and social context of Black youth behaviors and the importance of strengthening school-family partnerships (Marraccini et al., 2021a).

Implications

Research guiding clinical and school-based practices for preventing suicide in Black youth is virtually non-existent (Bath & Njoroge, 2020; Joe et al., 2018; Leong et al., 2013; Opara et al., 2020). Although there is a critical need for interventions designed to prevent suicide in Black youth, a paradigm shift in school-based identification and referral approaches could also play a critical role in preventing the death of Black boys. We therefore call on school psychologists to take a trauma- and JEDI-informed approach for preventing, identifying, assessing, and intervening in suicide risk (APA, 2018). This shift in paradigms is critical for prevention programs targeting Black youth given that dominant prevention programs have focused on problem behaviors and were born out of oppressive and anti-Black policies such as the war on drugs (Jagers, 2016). By modeling, teaching, and practicing anti-racist approaches in schools, school psychologists can play an essential role in disrupting some of the stressors that may contribute to suicide in Black boys who are perishing at an alarming rate.

A Trauma- and JEDI- Informed Approach to Suicide Prevention

Trauma-informed care acknowledges and identifies the presence and symptoms of trauma, and their influence on children, adults, cultural groups, and systems (SAMHSA, 2014). Trauma-informed schools integrate the key assumptions (i.e., realization, recognition, response, and resistance) and principles (i.e., safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment, voice, and choice; and cultural, historical, and gender issues) of trauma-informed care into evidence-based practices and systems level change (Chafouleas et al., 2016; O’Neill et al., 2021). Application of trauma-informed approach to research and practice with Black boys (and men) acknowledges the historical and on-going dehumanization of Black boys to help facilitate a change in the contemporary narrative about Black lives (Lee, 2016). Instead of taking a deficit-oriented approach that places blame on Black boys, a trauma-informed approach fosters compassion and empathy, allowing individuals to see the impact of trauma that may have previously been invisible to them (Lee, 2016).

By acknowledging and identifying the presence and symptoms of racial trauma, and their influence on suicide in Black boys; and by focusing on approaches to suicide prevention that build safety and trust, leverage peer supports, collaborate and partner with family and community members, and empower Black boys and Black liberation oriented professionals, we propose a model that builds off of the key principles of a trauma-informed approach for Black individuals (Chafouleas et al., 2016; Lee, 2016). Because a single intervention is unlikely to disrupt racial inequity (Gregory et al., 2017), we present a trauma-informed approach that integrates multiple JEDI frameworks: approaches for educational equity that aim to eradicate disparities in school discipline and other negative school outcomes (Gregory et al., 2017; Jagers et al., 2019) and recommendations for establishing culturally grounded approaches to school-based suicide prevention (Marraccini et al., 2021a; Opara et al., 2020; Singer et al., 2019).

A JEDI approach requires that schools uphold the principles of Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion. JEDI principles represent unique, but overlapping, constructs that play separate roles in fostering antiracism. Justice refers to the dismantling of obstructions to resources and opportunities (e.g., school-related supports and services) for all students to thrive, learn, and grow in schools. Multiple types of justice can be considered within schools. For example, social justice refers to equitable access to resources and opportunities, and being treated with fairness and respect (National Education Association, 2019; Shriberg et al., 2008); distributive justice relates to perceptions of fairness in terms of the distribution of resources and opportunities; and restorative justice aims to facilitate relationship-centered approaches to collaboratively solve problems (as opposed to the punitive disciplinary procedures typically taken in instances of behavioral concerns; Fronius et al., 2019).

Equity in schools (or educational equity) means providing the supports and services that students need to develop to their full potential – services and supports that need to be differentiated for individual students according to the barriers and obstructions they face, with specific attention to ethnic and racial minoritized students (racial equity; National Equity Project, n.d.). Diversity reflects differences across individuals (rooted in obstructions and privilege), and a recognition that diverse educators, staff, and students enrichen the school environment (National Association of School Psychologists [NASP], 2020). Finally, inclusion refers to practices that center the needs and voices of students (and educators and staff) facing obstacles and disadvantages to build a school community that provides them with sense of safety and belonging in which they can participate in authentic learning.

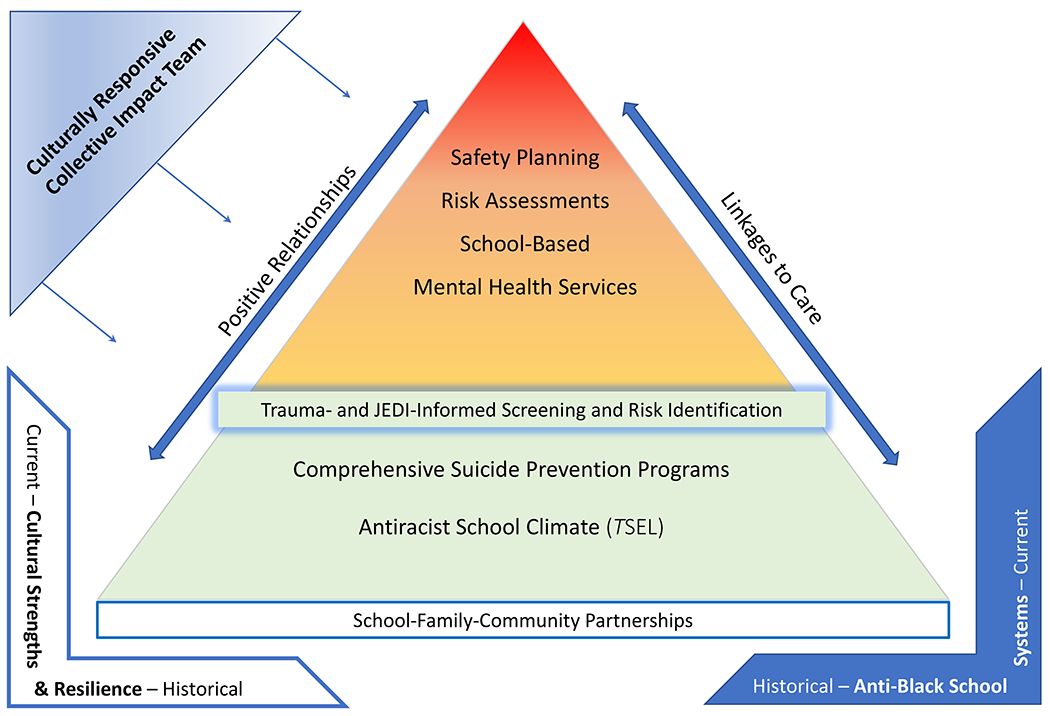

Framework for a Trauma- and JEDI-Informed Approach to Suicide Prevention

As shown in Figure 1, trauma- and JEDI-informed strategies for suicide prevention in Black boys are presented across the different tiers of a multi-tiered system of support (MTSS). Universal (Tier 1) prevention efforts, which target the general school population, include upstream approaches for fostering antiracist school climates and comprehensive, equitable suicide prevention programs. Inclusive screening and risk identification procedures are considered one of the pathways towards receiving selected and indicated (Tiers 2 and 3) approaches, which focus on youth identified for risk. Tier 2 and 3 strategies include safety planning, risk assessments conducted in schools, and school-based mental health interventions.

Figure 1. Trauma and JEDI-Informed Suicide Prevention Model in Schools.

Notes. JEDI = justice, equity, diversity, and inclusive; TSEL = transformative social and emotional learning.

Partnerships with the community and families are considered the foundation of this work; accordingly, strategies to support inclusive school-community-family partnerships are embedded across all levels of the model (and displayed at the base of the figure). These partnerships are strengthened by using a culturally responsive collective impact team (CR-CIT; Jones, 2017), shown in the top left of the figure. In a CR-CIT, school psychologists collaborate with other school, community, and cultural stakeholders to create collaborative communities that support a culturally grounded approach to MTSS. As described by Jones (2017), the CR-CIT shares responsibilities in leadership and decision making, with the goal of centering the cultural values and beliefs of Black (and other minoritized) youth, and also integrating these values and beliefs across disciplines. The exact individuals in the CR-CIT may vary, but should include cultural brokers or allies connected to schools (e.g., parents, language interpreters, and members of local community; Jones, 2017).5

Both linkages to care and positive relationships are presented as cross-cutting considerations integrated across all levels of MTSS. We describe linkages to care in the selected/indicated (Tiers 2 and 3) level; however, because they are relevant across tiers, we have represented them as an arrow that transects all tiers in the figure. Likewise, a key element across all the outlined strategies is for school psychologists and other adults to prioritize developing and maintaining positive relationships with Black boys, which is also represented across tiers.

Finally, as represented in the bottom left and right corners of the figure, this model is framed by acknowledgment of and accounting for the historical and sociopolitical influences on Black boys’ lives. Across all suicide prevention activities, a trauma and JEDI-informed approach must include recognition and nurturing of Black cultural strengths and resilience, as well as acknowledgement and rejection of anti-Black attitudes and climates in schools and communities. This framework aims to enhance protective factors against suicide, eradicate aggressive disciplinary referrals, and lay the groundwork for implementing culturally grounded school-based suicide prevention efforts focused on supporting Black boys. As Bath and Njoroge (2021) explain, “applying a JEDI lens means understanding structural racism and considering its implications through the continuum of care from prevention to treatment” (p. 19).

Tier 1, Universal Approaches

Universal suicide prevention programs in schools include: (1) upstream approaches that enhance protective factors and aim to prevent risk factors in youth from childhood through adolescence (Wyman, 2014); and (2) comprehensive suicide prevention programs designed to teach about and identify risk and connect youth to care (Singer et al., 2019). Accordingly, a trauma- and JEDI-informed approach to preventing suicide in Black boys at the universal level aims to facilitate a positive, anti-racist school climate that is culturally inclusive to Black boys and promotes positive school experiences (i.e., fostering positive student-adult relationships, student-student interactions, learning environments, and student leadership and other extracurricular opportunities; Chafouleas et al., 2016).

By establishing transformative social-emotional learning (TSEL) curriculums, schools can enhance skill development, promote collective action, and help to foster an anti-racist school climate (Chafouleas et al., 2016; Jagers, 2016; 2018). In addition to enhancing protective factors, these upstream approaches can help establish the strong relationships necessary for successful implementation of comprehensive suicide prevention programs, such as gatekeeper approaches, which provide education and training to community members in the school (Gould & Kramer, 2001). Systematic screenings should not only address risk for suicide and symptoms of trauma by surveying students, but they should also involve the monitoring of ongoing behavioral data. Because signs and symptoms of suicide and trauma may be masked as problem behaviors and aggression (e.g., Assari et al., 2018a), such monitoring is critical for distributive justice that irradicates inequitable disciplinary practices that contribute to mental health problems in Black youth. Because school and community resource availability may limit the extent to which schools can engage in all these processes (e.g., schools located in rural settings may have limited access to community mental health services; Wyman et al., 2010), upstream strategies are selected to leverage in-school resources and serve as an important foundational stage for suicide prevention irrespective of a school’s capacity to engage in additional services. Strategies are described in subsequent sections and shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Upstream Approaches: Transformative Social-Emotional Learning (TSEL)

The idea of taking an upstream approach to suicide prevention assumes that interventions effecting multiple risk factors, as opposed to a single risk factor, will have more success in fostering wellness and thus reducing rates of suicide (Wyman, 2014). Wyman (2014) describes a two-path approach towards preventing youth suicide: programs delivered to children that enhance self-regulation processes (e.g., behavior management programs) and interventions targeting adolescents that leverage peer connections to prevent risk behaviors and foster protective skills (e.g., Sources of Strength). As school psychologists select the most appropriate intervention tools and how best to wield them, it is critical that they intentionally center Black students’ wellness (Graves et al., 2021). Although there is evidence supporting interventions in each of these categories, studies of these interventions have infrequently disaggregated effects by racial groups (Joe et al., 2018) and none of the interventions focus on the unique risk and protective factors relevant for Black youth specifically.

Notable attention (e.g., Bowman-Perrott et al., 2016) has been given to the Good Behavior Game, a classroom management strategy that socializes children through team-based strategies to regulate behavior and has been evaluated in low-resourced, predominantly Black communities (Wilcox et al., 2008). Despite evidence that supports long-term effects for protecting against suicidal ideation (Wilcox et al., 2008), as described by Joe and colleagues (2018), data has not been disaggregated by race and effects have only clearly been supported in NLW youth. Although Sources of Strength is another promising intervention that appears well suited for tailoring according to varying school community needs and culture, evidence supporting its effectiveness for suicide-related outcomes largely rely on NLW samples (Wyman et al., 2010; Calear et al., 2016). In a study exploring the mechanisms of intervention exposure across individual and school-level characteristics, a lower proportion of Black students were selected to be peer leaders compared to NLW students, and boys and Black students were among the most likely to be isolated from peers and adults, lessening their exposure to the intervention (Pickering et al., 2018). Thus, implementation of these programs must prioritize inclusion of Black student leaders, especially given the stigma of mental health concerns and help-seeking that can prevent Black youth from connecting to care (Congressional Black Caucus, 2019).

Although no studies have evaluated a trauma- and JEDI-informed approach to universal suicide prevention in Black youth, we suggest the use of transformative social-emotional learning (TSEL) as an important first step in improving the school climate and enhancing protective factors against suicide and behavioral problems. Social and emotional learning is defined as “the process through which children and adults acquire and effectively apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions” (CASEL, 2021). Criticized for taking a colorblind approach and placing the onus on students (Gregory & Fergus, 2017), CASEL has begun to prioritize educational equity (Niemi, 2020). The idea of TSEL was first introduced by Jager and colleagues (2018; 2019) to explicitly integrate issues of power, privilege, prejudice, discrimination, social justice, empowerment, and self-determination into social-emotional learning.

Centralizing social and emotional learning around the concept of “engaged citizenship,” Jager and colleagues (2019) describe how the components within TSEL can be characterized as transformative and justice oriented, which hold distinct advantages over traditional views of social-emotional learning that encapsulate personally responsible and participatory practices. These latter approaches “align with conformist resistance that offers limited or no system critique and is motivated by surviving within the existing social order” (Jager et al., 2019; p. 165). To this end, TSEL curriculums adopt transformative practices to address competencies in each of the social and emotional learning components for both students and school professionals (Griffin et al., 2020; Jagers et al., 2018; 2019; Legette et al., 2020), many of which align to preventative strategies that have been suggested for increasing equity in school discipline (Gregory et al., 2017). In addition to student-focused supports, these efforts target teacher and school professional understanding and awareness of implicit bias and systemic racism, and make explicit their link to the inequitable disciplinary practices in Black youth (Jagers et al., 2018; Legette et al., 2020). As shown in Supplementary Table 1, there are several strategies that schools can employ to enhance each of the five domains of TSEL (self-awareness, self-management, responsible decision-making, relationship skills, and social awareness) as an upstream approach towards suicide prevention. Although future work exploring if TSEL relates to reduction in suicide-related risk and how best to integrate TSEL into a universal suicide prevention is warranted, application of these strategies may help set the stage for subsequent prevention programs (e.g., gatekeeper trainings).

Comprehensive Suicide Prevention Programs

There are several comprehensive suicide prevention programs designed for schools, such as suicide awareness curriculums, screenings, means restriction, and gatekeeper programs. Although limited by methodological weaknesses and minimal rigorous evaluations, programs that take a multi-method approach and combine comprehensive education to both students and adults, means restriction, gatekeeper trainings, and suicide-risk screenings across the levels of MTSS have demonstrated preliminary support (Pistone et al., 2019; Singer et al., 2019).

On-the-ground applications of school-based comprehensive suicide prevention programs that are equitable should avoid a “one size fits all” approach. Interventions should be culturally grounded and co-designed with school-community-family partnerships to match the needs of the schools’ student body and community (Marraccini et al., 2021a). For example, inclusive cultural adaptations selected in partnership with Black student consultants that were made to a cognitive-behavioral coping and stress prevention intervention (e.g., changes in language to fit common vernacular, visual representations of Black people, and concepts depicting Black heritage) were found to support suicide risk reduction in Black youth (Robinson et al., 2016). In a similar vein, suicide prevention programs should integrate partnerships with community supports most familiar with the cultural beliefs and practices of the community (Bluehen-Unger et al. 2017). By ensuring that key members of the CR-CIT with decision-making power regarding selection and adaptation of curricula and practice implementation are Black and/or Black liberation-oriented professionals (who are compensated and respected), schools can better align interventions with goals of serving Black boys.

In the following sections, we identify some of the core principles of suicide prevention programs, and provide strategies for integrating a trauma- and JEDI-informed approach to use as schools collaborate with students, families, and communities to develop and implement suicide prevention programs fitting their strengths and needs (see Supplementary Table 1). Recommendations are provided for school psychologists to consider as they engage with community and school partners in suicide prevention across two areas: (a) increasing knowledge and improving recognition of diversity within signs and symptoms of suicide; and (b) administering inclusive systematic screenings to identify students who may benefit from interventions or referrals.

Increasing Knowledge and Improving Recognition of Signs and Symptoms

School psychologists can enhance cultural sensitivity of approaches for understanding and recognizing risk by evaluating and revising training materials to include relevant risk and protective factors to Black boys. Although we provide an overview of considerations in Table 1, there is limited research identifying how symptoms of depression and trauma are expressed in Black boys or how warning signs of suicide may differ from other groups. The Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) does acknowledge cultural variations in symptoms of depression, but cautions against making direct linkages between specific cultures and symptoms. Yet, an initial evaluative step toward culturally sensitive practices with Black boys is to recognize that symptoms of depression and trauma are commonly misinterpreted as behavior problems that can trigger aggressive disciplinary procedures (e.g., Gregory & Weinstein, 2008; Stevenson, 2008).

Table 1.

Signs and Symptoms of Depression, Post-Traumatic Stress, and Suicide Risk

| Signs and Symptoms | Considerations for Black Boys | |

|---|---|---|

| Signs and symptoms associated with depressive disorders 1 | • Persistent depressed or irritable

mood • Changes in appetite or weight • Insomnia or hypersomnia • Low energy or fatigue • Low self-esteem or feelings of worthlessness • Poor concentration or difficulty making decisions • Feelings of hopelessness • Persistent suicide-related thoughts and behaviors |

• Internalizing symptoms may be viewed

as a weakness and be “self-masked” (Rochlen et al., 2010). • Internalizing symptoms may be “masked” by other problem behaviors, and thus overlooked (Assari et al., 2018a; Mallet, 2016; Rochlen et al., 2010). • Internalizing symptoms may display as irritability and aggression, as opposed to sadness and decreased energy (Clarke & Mosleh, 2015). • Symptoms of trauma may include avoidant symptoms and hypervigilance (Smith & Patton, 2016). • Black boys may be impacted by race-based traumatic stress (Carter, 2007). • Perceived constructs of masculinity influence coping dispositions utilized by Black boys (Addis & Mahalik, 2003). • Perceived constructs of masculinity may reinforce shame and stigma related to mental health problems (DuPont-Reyes et al., 2020; Lindsey et al. 2010) and interfere with help-seeking (e.g., verbalizations of suicidal ideation). • Violent and self-destructive behaviors may precipitate suicide in Black youth (Baker, 1990; Joe, 2006). |

| Signs and symptoms associated with criteria for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder 1 | • Intrusion (e.g.,

distressing memories or repetitive play, distressing dreams,

dissociative reactions or trauma-specific reenactment, distress or

physiological reactions to cues resembling trauma) • Avoidance of distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings, or external reminders of trauma • Negative alterations in mood or cognitions (e.g., inability to remember important aspect of event; negative beliefs about oneself, others, or the world; distorted cognitions about traumatic event; persistent negative state such as fear, horror, anger, guilt, shame; diminished interest or participation in activities; feelings of detachment), inability to experience positive emotions • Alterations in arousal or reactivity (e.g., irritable behavior and angry outbursts, reckless or self-destructive behavior, hypervigilance, exaggerated startle response, problems with concentration, sleep disturbance) |

|

| Warning signs associated with suicide risk 2 | • Mood (e.g., depression,

anxiety, loss of interest, irritability, humiliation and shame,

agitation and anger, and relief or sudden improvements) • Verbal (e.g., talking about killing themselves, feeling hopeless, having no reason to live, feeling like a burden, feeling trapped, and expressions of unbearable pain) • Behavioral (e.g., increase in alcohol or drug use, searching for methods, withdrawal, isolation, too much sleep, visiting people or saying goodbye, giving away important possessions, aggression, and fatigue) |

Because NLW health professionals have expressed discomfort with the “culturally rich jargon” used by African Americans and have been found to minimize symptoms in Black individuals (APA, 2018), professional development delivered to teachers and school professionals needs to explicitly address the detrimental and traumatic effects of racism on Black health (e.g., Gee & Ford, 2011) and teach approaches for self-monitoring biases. By creating a safe space for school professionals to look inward, suicide prevention trainings can help individuals to recognize their own biases and privilege, the societal and systems-level racism that both oppresses and capitalizes on Black lives, and the way school professionals are situated within these systems. This work can help school professionals acknowledge how these systems and interactions perpetuate the idea of problem behaviors in Black youth and lead to missed opportunities for connecting Black boys to school-based supports and mental health care.

By applying an anti-racism lens, school psychologists can be critical of referrals for “classroom disruptions” and “behavioral concerns” and consider the ways racial discrimination, cultural incongruencies, and symptoms of trauma experienced both in and out of school may better define these behaviors. These initial strategies for distributive justice regarding identifying and intervening in suicide risk must attend to the structural risks surrounding Black boys. Graves and colleagues (2021) identified coaching aimed at improving classroom management strategies as a promising intervention for reducing disciplinary referrals in minoritized students (Flynn et al., 2016), which could be integrated into trainings about signs and symptoms of suicide. Many of the strategies for integrating TSEL into the classroom may also be applied when training school professionals to engage in conversations with Black boys about suicide risk, particularly self-monitoring of implicit biases, active listening, and collaborative conversations. Finally, because social supports have been found to buffer the effects of stigma related to mental health concerns in Black boys (Lindsey et al., 2010), gatekeeper training programs and other interventions leveraging peer supports should prioritize Black boys as student leaders. Collaborating with Black boys around the appropriateness of the training materials can help facilitate cultural relevancy, inclusiveness, and intervention efficacy (e.g., Robinson et al., 2016).

Systematic Screenings

Universal suicide screenings include upstream approaches that aim to identify suicide-related risk factors such as depression, before a suicide-related crisis occurs, as well as surveys designed to assess suicide-related thoughts and behaviors (Singer et al., 2019). To enact distributive justice, we also recommend the use of data monitoring within upstream approaches to screening, that is, reviewing disciplinary referrals and connecting Black boys to care who may be less likely to be identified through the previously described screening approaches. Importantly, all comprehensive screening approaches require extensive preparation, including time to establish buy-in from parents, access to ample trained student support professionals to conduct follow-up assessments and support referrals, and a thorough list of community-based referrals prepared to provide treatment to identified youth (Mirick et al., 2018; Singer, 2017).

Upstream Approaches to Screening

Universal screenings for social, emotional, and behavioral concerns can identify youth with a myriad of risk factors, including those correlated with suicide, before a suicide-related crisis occurs (LeFevre, 2014; Singer et al., 2019). There are ample resources for engaging in these screenings using an MTSS framework (Battal et al., 2020), with preliminary evidence supporting their use with Black youth specifically (e.g., Lambert et al., 2018). Screenings administered with Black boys should also consider how socialization of Black boys may reinforce adherence to the traditional male role norms of coping, such as John Henryism, restrictive emotionality, and masculine self-reliance, which may influence how symptoms are expressed (Hammond, 2012; Matthews et al., 2013). Therefore, symptoms related to mood disorders specific to Black boys may be “self-masked” (Assari et al., 2018a; Mallet, 2016; Rochlen et al., 2010) and school professionals should consider mood and behavioral risk factors of suicide jointly. In addition to consideration of the clinical symptoms and risk factors shown in Table 1, school professionals should screen for irritability, aggression and violence, weapon carrying, hypervigilance and avoidance, substance use, and sexual behavior problems, which have been identified as symptoms of internalizing disorders in Black individuals (Simmons et al., in press; Smith & Patton, 2016).

In addition to these traditional screening methods, schools should also engage in data monitoring to identify the potential for subgroups or individual students overlooked for mental health care. Monitoring of disciplinary and mental health referrals together is an important strategy for identifying youth who may repeatedly be receiving disciplinary actions, but may benefit from social and emotional interventions instead. Though practices to prevent aggressive disciplinary referrals are considered part of the upstream approaches, it remains important to review disciplinary referrals regularly and intervene when youth are receiving discipline for problem behaviors that may better be explained by underlying mental health conditions. Working as part of the CR-CIT, school psychologists can help establish alternative interventions for these youth, and provide school-based mental health and/or referrals to community-based providers, in lieu of exclusive discipline. Outcomes from these efforts should, in part, be evaluated based on school-wide reviews of disciplinary referrals and policies that protect against aggressive discipline disaggregated by race and ethnicity.

Screening for Suicide-Related Thoughts and Behaviors

Recommendations vary regarding the evidence base for school-based screenings that explicitly assess suicidal ideation and behaviors (Arango et al., 2021; LeFevre, 2014; Singer et al., 2019). As of 2017, the National Registry of Evidence Based Programs and Practices identified only one evidence-based screening for suicide-related thoughts and behaviors (Signs of Suicide; Singer et al., 2019), but multiple evaluation studies have been conducted since the database was frozen by the White House in 2017 (see Arango et al., 2021). We therefore advise that school psychologists exert caution in engaging in screeners addressing suicide-related thoughts and behaviors, ensuring preparedness regarding culturally grounded and inclusive approaches to assessing risk, culturally sensitive discussions of risk with families, and appropriate linkages to care.

Two studies have explored school-based suicide screenings (Columbia Teen Screen and Columbia Health Screen) that included questions addressing both risk factors (e.g., negative mood) and suicide-related thoughts and behaviors with Black adolescents (Brown & Grumet, 2009; Husky et al., 2012). Findings from both studies indicated relatively low acceptance rates (i.e., agreement by the family or adult adolescent to complete the screener; 14% and 29%), high positive screen rates (45% and 45%), and high rates of connection to school-based mental health services (86% and 93%; Brown & Grumet, 2009; Husky et al., 2012). Although Black and White students reported comparable rates of suicide-related behaviors, significantly more Black youth asked for help for an emotional problem as compared to NLW students (Husky et al., 2012). Black students were also more likely than NLW students to access school-based services (93% compared to 76%) following the administration of the screeners (Brown & Grumet, 2009; Husky et al., 2012). In light of the lower likelihood for Black boys to report having suicidal ideation (Lindsey et al., 2019), findings further reinforce the importance of addressing indicators of affect and behavior in screenings (as opposed to relying on verbal indicators of thoughts of death) aimed at connecting Black youth to care.

As shown in Table 1 screenings addressing suicide-related risk should integrate cultural variations in mood (e.g., depression, anxiety, hopelessness), verbal expressions (e.g., talking about killing oneself), and behavioral factors (e.g., withdrawal and searching for methods to kill one self). The potential stigma and shame associated with mental health problems in Black boys (DuPont-Reyes et al., 2020; Lindsey et al., 2010) may reduce the saliency of verbal expressions of suicide. By proactively building peer-led support and risk identification procedures into the school community that prioritize the cultural wealth of Black boys, school professionals can avoid relying solely on verbal exchanges between students and adults as indicators of risk.

Selected and Indicated, Tier 2 and 3 Approaches

Selected and indicated approaches to suicide prevention include: (1) risk assessments to determine appropriate referrals or interventions; (2) collaborations with students, families, and providers in developing and supporting safety plans and monitoring risk; (3) linking youth to care in the school or community; and (4) school-based mental health interventions. Supplementary Table 2 displays trauma- and JEDI-informed suicide prevention strategies at tiers 2 and 3.

Risk Assessments

Although limited by minimal predictive validity (Silverman & Berman, 2014), risk assessments are considered a best practice approach for suicide prevention in schools (Crepeau-Hobson, 2013). Standard risk assessments involve interviews and observations to inquire about both current and past suicide-related thoughts and behaviors, risk factors, and protective factors (Crepeau-Hobson, 2013; Silverman & Berman, 2014). Typically, risk assessments involve multiple professionals, close monitoring of the student at risk, and collaborations with family and any treatment providers when making a suicide risk formulation. A trauma-informed approach applies a strengths-based framework during assessments, considering the strengths of the child, family, and culture for risk formulation, referrals, and safety planning (O’Neill et al., 2021).

To our knowledge, there are no culturally grounded risk assessment approaches designed for school settings. The Cultural Assessment of Risk of Suicide (CARS; Chu et al., 2017), which was designed for minoritized adults, provides some strategies for conducting risk assessments that may extend to Black boys. The CARS identifies risk and protective factors related to cultural sanctions (e.g., perceived shame of suicide), cultural idioms of distress-emotional/somatic (e.g., long-lasting anger), cultural idioms of distress-suicidal actions (e.g., access to lethal means), acculturative stress, minority stress (e.g., ethnic-racial discrimination), sexual and gender minority stress, family conflict, and social support. Although additional research exploring this risk assessment with youth is merited, school psychologists can consider the addition of these culturally bound stressors to standard risk assessments. Moreover, because stigma and shame related to mental health problems (e.g., DuPont-Reyes et al., 2020) may impact Black boys’ willingness to disclose suicidal thoughts or intent, open-ended questions that avoid mental health jargon may reveal more pertinent data to inform risk. For example, school psychologists can use behavioral-oriented terminology when asking questions, such as “How did you react when that happened?” as opposed to “How did you feel when that happened?”.

Safety Planning

Safety planning interventions are considered an evidence-based intervention for mitigating suicide risk in adults and adolescents (Drapeau, 2019). Safety planning may include the development of coping strategies, identification of sources of support and emergency contacts, plans for restricting access to lethal means, and increased monitoring by parents and caregivers (O’Neill et al., 2021). The degree to which safety planning is used in schools remains unclear (O’Neill et al., 2021); however, there is evidence of reductions in suicide risk in adolescent samples (Czyz et al., 2019) and safety planning is recommended to be integrated into school settings by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and others (AFSP et al., 2019).

Recently, O’Neill and colleagues (2021) described a trauma-informed approach to safety planning that emphasizes a collaborative approach for hope building that clearly defines plans that school personnel can draw upon in the case of increased intensity or the reemergence of risk in students. The researchers recommended integrating safety planning into school-based risk assessments, partnering with the student to encourage use of the plan instead of engaging in self-injury, and partnering with parents for restricting access to lethal means. In addition to integrating cultural sanctions (e.g., perceived shame of suicide), culturally bound stressors (e.g., discrimination), and culturally relevant protective factors (e.g., faith) into safety planning, school psychologists can address any misconceptions of suicide and rates within the Black community when informing parents about their child’s risk (when informing is deemed to not cause more harm). Dispelling the notion that suicide does not occur among Black youth or any tendency to minimize the threat could help establish more support for implementing the safety plan.

By discussing cultural wealth and resilience (e.g., positive racial identity development, spirituality, strong social relationships) and carefully listening to the student at the outset of safety planning, school professionals can build the trust required to tailor a safety plan to an individual’s strengths and needs. School professionals should explore the relevance of including specific race-related triggers or threats against masculinity and collaborate to select coping strategies that do not place additional stigma on the youth. For example, distractive coping, which involves intentionally shifting attention away from negative feelings or experiences towards neutral ones (e.g., playing sports, listening to music; Thomas et al., 2015) may be more acceptable than other coping strategies (e.g., deep breathing) that could be introduced later.

A final consideration for safety planning is identifying appropriate adults willing to provide immediate support as needed. Valuing social relationships and interdependence is a form of communalism rooted in Black culture and is integral to positive Black youth development (Gooden & McMahon, 2016). Identifying supportive individuals as part of safety planning should consider caregiver surrogates who may be part of the community and/or church, or who are family friends associated with a strong kinship tie (Simmons et al., in press). Ideally, school professionals will actively collaborate with the CR-CIT to build a network of Black and Black liberation-oriented adults in the school or community available to serve in these roles.

Linkages to Care

Linkages to care involve in-school referrals, wherein gatekeepers refer students of concern to specific individuals (e.g., school psychologists, school counselors) who engage in secondary or tertiary services to identify risk, and also involve referrals to community-based providers, school-based mental health, and emergency services. Because there are costs to overreliance on referrals to emergency departments, including the immediate stress faced by students and families and the financial costs associated with emergency care, it is best to reserve referrals to hospitalizations for those at imminent risk for suicide (e.g., suicidal ideation including a clear plan with intent to act, access to lethal means; O’Neill et al., 2021).

School psychologists can help ensure referrals are approached with cultural sensitivity by establishing pathways to brief interventions through community-school-family partnerships (Marraccini et al., 2021a; O’Neill et al., 2021). One strategy involves community asset mapping, in which schools collaborate with other organizations (e.g., congregations, non-profits, community centers) to explore how problems across sectors overlap, and engage in coordinated problem-solving to address a common goal (Griffin & Farris, 2010). These partnerships can map a continuum of services, from universal suicide prevention approaches (e.g., identification and connection to Black role models in the community; extracurriculars devoted to positive racial identity, Black history, and culture) to indicated interventions (e.g., network of treatment providers using culturally grounded practices for Black youth and families).

School-Based Mental Health Services