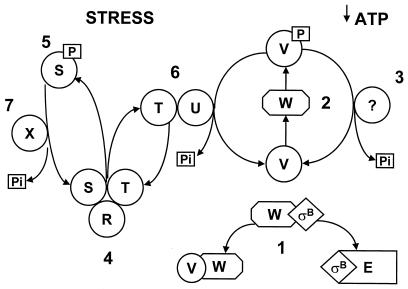

FIG. 1.

Model of ςB regulation. (Step 1) The anti-ςB protein RsbW (W) can form a mutually exclusive complex with either ςB or RsbV (V) (6, 9). When bound to RsbW, ςB is unavailable to RNA polymerase (E) (6). RsbV binding to RsbW allows the release of ςB and the formation of a ςB RNAP polymerase holoenzyme (E-ςB) (6). (Step 2) With ATP as a phosphate donor, RsbW can phosphorylate RsbV (2, 9). RsbV-P (V-P) is inactive as a ςB release factor (2, 9). During growth, relatively high ATP levels favor the phosphorylation and inactivation of RsbV, leaving ςB bound to RsbW (2, 38). If ATP levels fall, as when B. subtilis enters stationary phase, the phosphorylation of RsbV may be inefficient, leading to the persistence of active RsbV, the formation of RsbV-RsbW complexes, and the release of ςB (2, 38). (Step 3) The magnitude of the low-ATP activation of ςB is enhanced by dephosphorylation of a portion of the RsbV-P by an unknown mechanism (37). (Step 6) Environmental stress (e.g., heat shock, osmotic shock, and ethanol treatment) activates an RsbV-P phosphatase, RsbU (U), which creates active RsbV, regardless of ATP levels (37). (Step 4) RsbT (T), the activator of RsbU, is normally inactive due to an association with a negative regulator RsbS (S) (41). RsbR (R), an additional regulatory protein, binds to RsbS and RsbT (31) and is believed to play a structural role and to facilitate RsbT-RsbS interactions (1, 12). (Step 5) Upon exposure to stress, RsbT phosphorylates and inactivates RsbS and activates the RsbU phosphatase (12, 31). (Step 7) RsbS-P is dephosphorylated and reactivated by a phosphatase, RsbX (X) (31), which is encoded by one of the genes downstream of the sigB operon’s ςB-dependent promoter (17). RsbX levels increase with increasing ςB activity (10). This may serve to limit the activation process and return RsbT to an inactive complex with RsbS.