Abstract

Objective

Identify prevalence of self-reported swallow, communication, voice and cognitive compromise following hospitalisation for COVID-19.

Design

Multicentre prospective observational cohort study using questionnaire data at visit 1 (2–7 months post discharge) and visit 2 (10–14 months post discharge) from hospitalised patients in the UK. Lasso logistic regression analysis was undertaken to identify associations.

Setting

64 UK acute hospital Trusts.

Participants

Adults aged >18 years, discharged from an admissions unit or ward at a UK hospital with COVID-19.

Main outcome measures

Self-reported swallow, communication, voice and cognitive compromise.

Results

Compromised swallowing post intensive care unit (post-ICU) admission was reported in 20% (188/955); 60% with swallow problems received invasive mechanical ventilation and were more likely to have undergone proning (p=0.039). Voice problems were reported in 34% (319/946) post-ICU admission who were more likely to have received invasive (p<0.001) or non-invasive ventilation (p=0.001) and to have been proned (p<0.001). Communication compromise was reported in 23% (527/2275) univariable analysis identified associations with younger age (p<0.001), female sex (p<0.001), social deprivation (p<0.001) and being a healthcare worker (p=0.010). Cognitive issues were reported by 70% (1598/2275), consistent at both visits, at visit 1 respondents were more likely to have higher baseline comorbidities and at visit 2 were associated with greater social deprivation (p<0.001).

Conclusion

Swallow, communication, voice and cognitive problems were prevalent post hospitalisation for COVID-19, alongside whole system compromise including reduced mobility and overall health scores. Research and testing of rehabilitation interventions are required at pace to explore these issues.

Keywords: ARDS, COVID-19, critical care, pneumonia

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

COVID-19 is a multisystem disease with primary and potentially long-lasting impacts on respiratory function, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, circulatory, cardiac and nervous systems.

We do not yet know what the impact on swallow, communication, voice and cognition are post hospitalisation, so we explored what longer-term functional problems people experienced.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

We now know that swallow, communication, voice and cognitive problems are prevalent post hospitalisation for COVID-19 and were commonly associated with being younger, female and living in socially deprived areas.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This study tells us a significant number of people are experiencing swallow communication voice and cognitive issues, and they are likely to require support and effective rehabilitation to improve their function.

Future research and phenotype determination need to capture swallow, communication, voice and cognition subtypes, using detailed assessments and measurements of these important symptoms so we can improve outcomes.

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 has complex and multifaceted effects and results in the multisystem disease COVID-19. The primary impact of the virus and its variants are on respiratory function; however musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, circulatory, cardiac and nervous systems can also be compromised.1–4 Many experience symptoms persisting beyond 4 weeks from initial presentation, irrespective of severity of acute illness (long COVID).5 Our analysis explores data from PHOSP-COVID,6 which collected holistic clinical information from a large cohort of patients hospitalised with COVID-19 across the UK to determine chronic health sequelae. To date, there are no population-based studies on the prevalence of self-reported swallowing, communication, voice and cognitive problems post-COVID-19.

Swallowing problems and COVID-19

Causes of swallow compromise following COVID-19 are multifactorial. For those intubated and ventilated in hospital, iatrogenic injury to the larynx and upper airway frequently impacts on anatomy fundamental to safe and effective swallowing.7 Numerous patients who were not ventilated also experienced swallowing problems8 associated with respiratory compromise, neurological issues, encephalopathies and pre-existing comorbidities.9 10 Respiration and swallowing occur in synchrony via neural mechanisms. Consequently, when breathing is impacted by disease or respiratory support,11 destabilisation of the breathe-swallow pattern can result in aspiration (food and/or drink passing below the level of the vocal cords and into the trachea).11 This can cause a range of consequences from coughing and choking during eating and drinking to pneumonia and death.12

Communication and cognitive difficulties in COVID-19

Communication compromise may arise from a range of aetiologies associated with numerous pathologies.13 Word finding difficulties post COVID-19 have been described,14 potentially due to encephalopathies and associated dysexecutive syndromes. However no studies have prospectively investigated this symptom, its severity or recovery trajectory. Alongside communication issues, ‘brain fog’6 15 and neurocognitive problems16 have been reported.15 People may experience language deficits (dysphasia), or a conglomerate of symptoms involving language production and processing, and concurrent cognitive challenges which simultaneously impact on memory, perception, attention and reasoning. These cognitive processes are core components of successful communicative interactions and language use.17 These problems can be insidious and physically difficult for the individual to describe due to the nature of compromised language function.18

Voice and COVID-19

Voice changes (dysphonia) have been identified in both the acute presentation of the virus in hospitalised patients19; and in up to 43% of non-hospitalised patients.20 Laryngeal injury including vocal fold palsy can be a consequence of intubation and postviral infection,21 along with alteration to the physiology of the larynx and upper airway causing voice changes. Voice and vocal competence are fundamental to communication, and essential for individuals to work and function effectively in society.22 Significant distress has been reported as an effect of an inability to communicate.23 Impaired voice competence is an immediate and long-term risk to individual function, quality of life and ability to return to work, therefore a socioeconomic burden to the UK workforce.24

Clinical questions

What is the prevalence of swallow, voice, communication and cognitive problems after discharge from hospital following COVID-19?

What were the associations with individual characteristics in those who experienced these issues?

Methods

Methods, analysis and results are reported in line with Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.25 Prevalence of swallow, voice, communication and cognitive problems are reported, this is the proportion of the population included in the PHOSP data collection at and during particular time points, who self-reported these particular functional compromise.26

Data source

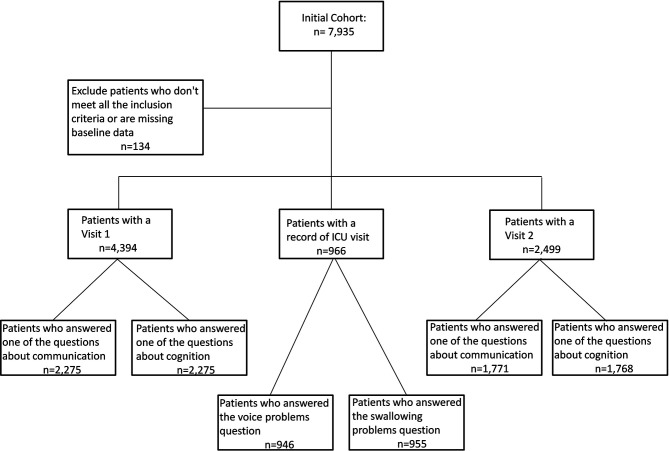

Data from PHOSP-COVID6 that recruited adult patients discharged from a ward or admissions unit at 64 UK hospital Trusts, with confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 were analysed to explore swallow communication, voice and cognitive symptoms. Participants were asked to complete two research visits; between 2–7 (visit 1) and 10–14 months (visit 2) post discharge, visits outside this timeframe were excluded (±14 days). Outcomes of interest were all derived from questionnaire responses completed at research visits. A number of participants were unable to attend their first visit but attended the second and therefore respondents included in the cohort at visit 2 may not have been in the visit 1 cohort (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart. ICU, intensive care unit.

Variables

Six outcomes of interest were self-reported communication issues and cognitive issues at visits 1 and 2, and self-reported voice and swallow problems during an intensive care unit (ICU) stay at some point in the index admission. Only people treated in ICU were asked whether they had voice or swallow problems. We defined someone as having a communication issue at either visit if they answered ‘yes’/‘yes—some difficulty’/‘yes—a lot of difficulty’ or ‘cannot do at all’ to “Using your usual (customary) language, do you have difficulty communicating, for example, understanding or being understood” or if they answered ‘yes’ to having ‘difficulty with communication’ within the last 7 days. Cognitive symptoms were identified if the respondent stated they had at least one of the following within the last 7 days; ‘confusion or fuzzy head’, ‘difficulty with concentration’, ‘short-term memory loss’, ‘physical slowing down’ or ‘slowing down in your thinking’. Swallowing and voice data were only collected from respondents who stated they had been admitted to ICU and answered ‘yes’ to either CRF question 3 “Are you having difficulties eating, drinking or swallowing such as coughing, choking or avoiding any food or drinks?” or the Patient Symptom Questionnaire (PSQ) “Have you or your family noticed any changes to your voice such as difficulty being heard, altered quality of the voice, your voice tiring by the end of the day or an inability to alter the pitch of your voice?” Any comorbidities listed as ‘other’ were reviewed individually and categorised, ensuring comprehensive data were included. Number of comorbidities were calculated as a count and treated as a continuous variable. Respondents’ body mass indices (BMI) were not collected at baseline but were collected at each of the follow-up visits.

Outcome measures

Relationships between six outcome variables and factors from the baseline visit were investigated, with further outcomes from questionnaires at both visits 1 and 2. We used the EQ-5D-5L27 health-related quality-of-life questionnaire, the Medical Research Council (MRC) Dyspnoea Scale,28 Dyspnoea 12,29 the Post-traumatic Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), a 20-item questionnaire which assesses the requirements for a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (overall score was categorised into 0–32 unlikely to have PTSD, and 33–80 indicative of probable PTSD) as per guidance,30 the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) assessment of cognition, visuospatial abilities, short-term memory, attention, working memory, language and orientation31 presenting a summary of the overall score, categorised as per published guidance31 into normal (>25), mild (18–25) and moderate or severe cognitive impairment (<18), and finally the Rockwood Clinical Frailty (RCF) score,32 a clinical measure of frailty from 1 (very fit) to 9 (terminally ill). We categorised the RCF into 1–4 (fit to vulnerable) and 5+ (mildly frail to terminally ill).

Explanatory variables: age and ethnicity were grouped and distributed. Respondents’ postcodes were linked to Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD)33 to provide an estimate of deprivation. We detailed ranked quintiles of IMD, 1 being most, 5 being least deprived.33

All levels of respiratory support during index admission were captured, with a combined variable relating to the WHO clinical progression scale. WHO respiratory support classification was ‘class 7–9’ for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), renal replacement therapy (RRT) or invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), ‘class 6’ for high flow nasal O2 (HFN), bi-level non-invasive ventilation (NIV), continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), ‘class 5’ for supplemental O2 and ‘class 4’ if the patient received none of these interventions.

Statistical methods

Respondents missing age, sex and gender were excluded from analysis. Categorical variables are reported as counts and percentages; continuous variables are presented as medians with IQRs. Univariable analysis of categorical variables was undertaken using either χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for small numbers, for continuous variables the Kruskal-Wallis test was used. Only completed data have been included for the summaries of the in-hospital, pre-hospital and outcomes. Although included in our protocol, after reviewing data for maximal inspiratory pressure and maximal expiratory pressure, handgrip and quadriceps strength and chest X-ray findings, we decided not to investigate these further due to incomplete data. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Before multivariable analyses were undertaken, a subset of variables were chosen to be included based on clinical knowledge. From the demographics section, we chose to exclude healthcare worker status and shielding status, the only COVID-19 symptoms included were cough, fever, headache confusion or other symptoms relating to ear, nose or throat problems, all comorbidities, new diagnoses, pre-admission medications and respiratory support were included. We only included antibiotic therapy, systemic steroids, therapeutic dose anticoagulation and RRT as these were treatment options available for the whole time period. For respondents included in the study, we included unknown categories for missing data in the baseline demographics in the multivariable analysis. For any pre-hospital or in-hospital variables included in the multivariable analysis, we included an unknown category.

We undertook lasso logistic regression with the binary outcomes of swallow, communication, voice or cognitive problems as the dependent variable for variable selection. We investigated a number of techniques including cross validation with 10 folds, adaptive lasso and elasticnet and chose the solution with the best out of sample model goodness of fit. We required age at admission and sex be included in the final models given their contextual importance.34 As a sensitivity analysis, we performed a complete-case analysis.

Results

Overall, 7935 participants were included in the study, n=134 were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria or had missing data. N=4394 had visit 1 data, n=966 had an intensive care unit visit and n=2499 had a visit 2 (see figure 1). Swallow, communication, voice and cognitive problems were prevalent and persisted over time from visit 1 to visit 2 (see tables 1 and 2). Swallow problems were reported in 20% (188/955) and voice problems in 34% (319/946) of those admitted to ICU. Of the whole cohort, communication issues were reported by 23.2% (527/2275) at visit 1 which remained at 22.5% (399/1771) at visit 2. Cognitive problems were more highly prevalent and reported by 70.2% (1598/2275) at visit 1, and remained at 69.6% (1231/1768) at visit 2.

Table 1.

Demographics of patients who answered questions about voice and swallow problems during their index admission

| ICU swallow problems | ICU voice problems | ||||||

| No | Yes | P value | No | Yes | P value | ||

| N (%) | 767 (80.3%) | 188 (19.7%) | 627 (66.3%) | 319 (33.7%) | |||

| Age at admission (years) | Median* (IQR) | 60 (51–67) | 57 (51–64.5) | 0.001 | 60 (51–68) | 59 (52–64) | 0.071 |

| Under 40 | 48 (6.3%) | 14 (7.4%) | 0.026 | 47 (7.5%) | 14 (4.4%) | 0.012 | |

| 40–49 | 105 (13.7%) | 26 (13.8%) | 79 (12.6%) | 50 (15.7%) | |||

| 50–59 | 216 (28.2%) | 73 (38.8%) | 177 (28.2%) | 106 (33.2%) | |||

| 60–69 | 260 (33.9%) | 53 (28.2%) | 203 (32.4%) | 110 (34.5%) | |||

| 70–79 | 138 (18.0%) | 22 (11.7%) | 121 (19.3%) | 39 (12.2%) | |||

| Sex | Female | 219 (28.6%) | 68 (36.2%) | 0.041 | 187 (29.8%) | 97 (30.4%) | 0.853 |

| Male | 548 (71.4%) | 120 (63.8%) | 440 (70.2%) | 222 (69.6%) | |||

| Ethnicity | White | 548 (71.4%) | 127 (67.6%) | 0.102 | 446 (71.1%) | 223 (69.9%) | 0.915 |

| South Asian | 79 (10.3%) | 27 (14.4%) | 67 (10.7%) | 39 (12.2%) | |||

| Black | 75 (9.8%) | 12 (6.4%) | 57 (9.1%) | 28 (8.8%) | |||

| Other† | 65 (8.5%) | 22 (11.7%) | 57 (9.1%) | 29 (9.1%) | |||

| BMI | Under/Normal weight | 52 (6.8%) | 10 (5.3%) | 0.237 | 43 (6.9%) | 19 (6.0%) | 0.153 |

| Overweight | 196 (25.6%) | 52 (27.7%) | 160 (25.5%) | 84 (26.3%) | |||

| Obese | 271 (35.3%) | 70 (37.2%) | 212 (33.8%) | 127 (39.8%) | |||

| Severe obesity | 67 (8.7%) | 23 (12.2%) | 58 (9.3%) | 31 (9.7%) | |||

| Not recorded | 181 (23.6%) | 33 (17.6%) | 154 (24.6%) | 58 (18.2%) | |||

| IMD quintile‡ | 1—most deprived | 175 (22.8%) | 40 (21.3%) | 0.528 | 140 (22.3%) | 75 (23.5%) | 0.121 |

| 2 | 170 (22.2%) | 50 (26.6%) | 150 (23.9%) | 65 (20.4%) | |||

| 3 | 155 (20.2%) | 40 (21.3%) | 115 (18.3%) | 75 (23.5%) | |||

| 4 | 135 (17.6%) | 25 (13.3%) | 115 (18.3%) | 40 (12.5%) | |||

| 5—least deprived | 130 (16.9%) | 35 (18.6%) | 100 (15.9%) | 60 (18.8%) | |||

| Unknown | § | § | § | § | |||

| Educational level | None | 42 (5.5%) | 8 (4.3%) | 0.135 | 39 (6.2%) | 10 (3.1%) | 0.331 |

| Primary school | 219 (28.6%) | 53 (28.2%) | 180 (28.7%) | 89 (27.9%) | |||

| Secondary school | 94 (12.3%) | 20 (10.6%) | 72 (11.5%) | 42 (13.2%) | |||

| Sixth form college | 98 (12.8%) | 35 (18.6%) | 82 (13.1%) | 50 (15.7%) | |||

| Vocational qualification | 131 (17.1%) | 24 (12.8%) | 106 (16.9%) | 48 (15.0%) | |||

| Undergraduate | 103 (13.4%) | 20 (10.6%) | 76 (12.1%) | 46 (14.4%) | |||

| Postgraduate | 80 (10.4%) | 28 (14.9%) | 72 (11.5%) | 34 (10.7%) | |||

| Unknown | 91 (11.9%) | 24 (12.8%) | 66 (10.5%) | 47 (14.7%) | |||

| Healthcare worker | 494 (64.4%) | 111 (59.0%) | 0.273 | 398 (63.5%) | 201 (63.0%) | 0.128 | |

| Shielding status prior to admission | Not | 130 (16.9%) | 30 (16.0%) | 0.145 | 108 (17.2%) | 50 (15.7%) | 0.653 |

| Voluntary shielding | 32 (4.2%) | 11 (5.9%) | 25 (4.0%) | 18 (5.6%) | |||

| Extremely vulnerable | 57 (7.4%) | 13 (6.9%) | 48 (7.7%) | 21 (6.6%) | |||

| Letter issued by HCP | 54 (7.0%) | 23 (12.2%) | 48 (7.7%) | 29 (9.1%) | |||

| Unknown | 175 (22.8%) | 40 (21.3%) | 140 (22.3%) | 75 (23.5%) | |||

Unless otherwise specified, numbers are shown as counts (percentages) and p values have been calculated using χ2 test; 20% of respondents who answered the question had swallow problems, patients were significantly more likely to be younger and female; 34% of respondents voice problems; there do not appear to be any significant differences in the demographics of patients who had voice problems compared with those who did not.

*P value calculated using Kruskal-Wallis, p<0.05 are bolded.

†Includes mixed and unknown.

‡Where numbers could be calculated, the other values have been rounded to the nearest 5 and % calculated on this new value.

§Numbers ≤5 have been suppressed.

BMI, body mass index; HCP, healthcare professional; ICU, intensive care unit; IMD, indices of multiple deprivation.

Table 2.

Demographics at the time of initial COVID-19 admission split by whether respondents have communication or cognitive issues at visit 1 or visit 2

| Visit 1 cognitive issues | Visit 2 cognitive issues | Visit 1 communication issues | Visit 2 communication issues | ||||||||||

| No | Yes | P value | No | Yes | P value | No | Yes | P value | No | Yes | P value | ||

| N (%) | 677 (29.8%) | 1598 (70.2%) | 537 (30.4%) | 1231 (69.6%) | 1748 (76.8%) | 527 (23.2%) | 1372 (77.5%) | 399 (22.5%) | |||||

| Age at admission (years) | Median* (IQR) | 60 (49–68) | 58 (50–66) | 0.976 | 60 (50–68) | 60 (52–68) | 0.361 | 60 (51–68) | 56 (49–63) | <0.001 | 61 (52.5–69) | 57 (51–64) | <0.001 |

| Under 40 | 64 (9.5%) | 118 (7.4%) | 0.002 | 49 (9.1%) | 68 (5.5%) | 0.102 | 142 (8.1%) | 40 (7.6%) | <0.001 | 86 (6.3%) | 31 (7.8%) | <0.001 | |

| 40–49 | 106 (15.7%) | 252 (15.8%) | 74 (13.8%) | 159 (12.9%) | 262 (15.0%) | 96 (18.2%) | 172 (12.5%) | 61 (15.3%) | |||||

| 50–59 | 158 (23.3%) | 494 (30.9%) | 143 (26.6%) | 368 (29.9%) | 451 (25.8%) | 201 (38.1%) | 362 (26.4%) | 151 (37.8%) | |||||

| 60–69 | 203 (30.0%) | 461 (28.8%) | 163 (30.4%) | 378 (30.7%) | 528 (30.2%) | 136 (25.8%) | 432 (31.5%) | 110 (27.6%) | |||||

| 70–79 | 119 (17.6%) | 225 (14.1%) | 91 (16.9%) | 214 (17.4%) | 299 (17.1%) | 45 (8.5%) | 265 (19.3%) | 38 (9.5%) | |||||

| 80 and over | 27 (4.0%) | 48 (3.0%) | 17 (2.2%) | 44 (3.6%) | 66 (3.8%) | 9 (1.7%) | 55 (4.0%) | 8 (2.0%) | |||||

| Sex | Female | 186 (27.5%) | 699 (43.7%) | <0.001 | 140 (26.1%) | 525 (42.6%) | <0.001 | 631 (36.1%) | 254 (48.2%) | <0.001 | 490 (35.7%) | 177 (44.4%) | 0.002 |

| Male | 491 (72.5%) | 899 (56.3%) | 397 (73.9%) | 706 (57.4%) | 1117 (63.9%) | 273 (51.8%) | 882 (64.3%) | 222 (55.6%) | |||||

| Ethnicity | White | 458 (67.7%) | 1243 (77.8%) | <0.001 | 382 (71.1%) | 980 (79.6%) | <0.001 | 1297 (74.2%) | 405 (76.9%) | 0.629 | 1060 (77.3%) | 304 (76.2%) | 0.404 |

| South Asian | 103 (15.2%) | 153 (9.6%) | 69 (12.8%) | 92 (7.5%) | 203 (11.6%) | 53 (10.1%) | 126 (9.2%) | 35 (8.8%) | |||||

| Black | 61 (9.0%) | 99 (6.2%) | 44 (8.2%) | 78 (6.3%) | 123 (7.0%) | 36 (6.8%) | 98 (7.1%) | 25 (6.3%) | |||||

| Other† | 55 (8.1%) | 103 (6.4%) | 42 (7.8%) | 81 (6.6%) | 125 (7.2%) | 33 (6.3%) | 88 (6.4%) | 35 (8.8%) | |||||

| BMI | Under/Normal weight | 68 (10.0%) | 137 (8.6%) | <0.001 | 61 (11.4%) | 85 (6.9%) | <0.001 | 166 (9.5%) | 39 (7.4%) | 119 (8.7%) | 27 (6.8%) | 0.047 | |

| Overweight | 197 (29.1%) | 390 (24.4%) | 163 (30.4%) | 285 (23.2%) | 456 (26.1%) | 131 (24.9%) | 0.259 | 365 (26.6%) | 83 (20.8%) | ||||

| Obese | 231 (34.1%) | 611 (38.2%) | 176 (32.8%) | 460 (37.4%) | 645 (36.9%) | 196 (37.2%) | 487 (35.5%) | 150 (37.6%) | |||||

| Severe obesity | 45 (6.6%) | 191 (12.0%) | 27 (5.0%) | 122 (9.9%) | 170 (9.7%) | 66 (12.5%) | 110 (8.0%) | 40 (10.0%) | |||||

| Not recorded | 136 (20.1%) | 269 (16.8%) | 110 (20.5%) | 279 (22.7%) | 311 (17.8%) | 95 (18.0%) | 291 (21.2%) | 99 (24.8%) | |||||

| IMD quintile‡ | 1—most deprived | 142 (21.0%) | 388 (24.3%) | 0.149 | 100 (18.6%) | 300 (24.4%) | <0.001 | 390 (22.3%) | 140 (26.6%) | 0.010 | 308 (22.4%) | 95 (23.8%) | 0.020 |

| 2 | 162 (23.9%) | 367 (23.0%) | 110 (20.5%) | 275 (22.3%) | 390 (22.3%) | 135 (25.6%) | 276 (20.1%) | 108 (27.1%) | |||||

| 3 | 132 (19.5%) | 265 (16.6%) | 100 (18.6%) | 220 (17.9%) | 300 (17.2%) | 95 (18.0%) | 250 (18.2%) | 65 (16.3%) | |||||

| 4 | 110 (16.2%) | 274 (17.1%) | 100 (18.6%) | 220 (17.9%) | 320 (18.3%) | 65 (12.3%) | 262 (19.1%) | 59 (14.8%) | |||||

| 5—least deprived | 123 (18.2%) | 296 (18.5%) | 125 (23.3%) | 215 (17.5%) | 330 (18.9%) | 90 (17.1%) | 269 (19.6%) | 72 (18.0%) | |||||

| Unknown | 8 (1.2%) | 8 (0.5%) | § | § | § | § | 7 (0.5%) | 0 | |||||

| Educational level | None | 14 (2.1%) | 46 (2.9%) | <0.001 | 10 (1.9%) | 34 (2.8%) | 0.008 | 44 (2.5%) | 16 (3.0%) | 0.009 | 36 (2.6%) | 9 (2.3%) | 0.020 |

| Primary school | 14 (2.1%) | 40 (2.5%) | 10 (1.9%) | 26 (2.1%) | 43 (2.5%) | 11 (2.1%) | 30 (2.2%) | 6 (1.5%) | |||||

| Secondary school | 166 (24.5%) | 511 (32.0%) | 161 (30.0%) | 393 (31.9%) | 519 (29.7%) | 159 (30.2%) | 429 (31.3%) | 126 (31.6%) | |||||

| Sixth form college | 97 (14.3%) | 198 (12.4%) | 63 (11.7%) | 161 (13.1%) | 225 (12.9%) | 70 (13.3%) | 159 (11.6%) | 65 (16.3%) | |||||

| Vocational qualification | 65 (9.6%) | 204 (12.8%) | 50 (9.3%) | 165 (13.4%) | 185 (10.6%) | 84 (15.9%) | 157 (11.4%) | 59 (14.8%) | |||||

| Undergraduate | 142 (21.0%) | 258 (16.1%) | 106 (19.7%) | 198 (16.1%) | 329 (18.8%) | 70 (13.3%) | 255 (18.6%) | 49 (12.3%) | |||||

| Postgraduate | 109 (16.1%) | 197 (12.3%) | 95 (17.7%) | 149 (12.1%) | 242 (13.8%) | 64 (12.1%) | 193 (14.1%) | 51 (12.8%) | |||||

| Unknown | 70 (10.3%) | 144 (9.0%) | 42 (7.8%) | 105 (8.5%) | 161 (9.2%) | 53 (10.1%) | 113 (8.2%) | 34 (8.5%) | |||||

| Healthcare worker | 84 (12.4%) | 238 (14.9%) | 0.252 | 70 (13.0%) | 180 (14.6%) | 0.210 | 230 (13.2%) | 91 (17.3%) | 0.010 | 186 (13.6%) | 64 (16.0%) | 0.452 | |

| Shielding status prior to admission | Not | 464 (68.5%) | 988 (61.8%) | <0.001 | 377 (70.2%) | 750 (60.9%) | 0.001 | 1142 (65.3%) | 309 (58.6%) | 0.001 | 884 (64.4%) | 244 (61.2%) | 0.091 |

| Voluntary shielding | 112 (16.5%) | 284 (17.8%) | 91 (16.9%) | 226 (18.4%) | 309 (17.7%) | 88 (16.7%) | 253 (18.4%) | 65 (16.3%) | |||||

| Extremely vulnerable | 24 (3.5%) | 99 (6.2%) | 21 (3.9%) | 79 (6.4%) | 83 (4.7%) | 40 (7.6%) | 75 (5.5%) | 26 (6.5%) | |||||

| Letter issued by HCP | 24 (3.5%) | 121 (7.6%) | 22 (4.1%) | 91 (7.4%) | 96 (5.5%) | 49 (9.3%) | 77 (5.6%) | 36 (9.0%) | |||||

| Unknown | 53 (7.8%) | 106 (6.6%) | 26 (4.8%) | 85 (6.9%) | 118 (6.8%) | 41 (7.8%) | 83 (6.0%) | 28 (7.0%) | |||||

Unless otherwise specified, numbers are shown as counts (percentages) and p values have been calculated using χ2 test; 70% of respondents at both visits 1 and 2 reported cognitive issues, and 23% of respondents reported communication issues. There did not appear to be significant difference in the proportion of patients who reported problems by whether or not they were healthcare workers. For communication issues, there did not appear to be any significant difference based on ethnicity or BMI.

*P value calculated using Kruskal-Wallis, p<0.05 are bolded.

†Includes mixed and unknown.

‡Where numbers could be calculated, the other values have been rounded to the nearest 5 and % calculated on this new value.

§Numbers ≤5 have been suppressed.

BMI, body mass index; HCP, healthcare professional; IMD, indices of multiple deprivation.

Swallow problems

Only participants who had been treated in ICU could report swallow problems. Important clinical features included the following: they were more likely to have undergone IMV (p<0.001), to have been proned (p=0.039) (table 3), to be younger (p=0.001) and female (p=0.041) (table 1). Significant physiological comorbidities associated with swallow problems were asthma (26% vs 16%, p=0.002) and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (15% vs 8%, p=0.002) (table 4). There did not appear to be any difference in ethnicity, education, deprivation, healthcare worker or shielding status prior to admission.

Table 3.

COVID-19 symptoms and treatments before and during the index admission for respondents who answered questions about voice or swallow problems

| ICU swallow* | ICU voice* | ||||||

| No | Yes | P value | No | Yes | P value | ||

| Duration of COVID-19 symptoms | Median (IQR)† | 8 (6–11) | 8 (6–12) | 0.791 | 8 (6–11) | 8 (6–12) | 0.228 |

| COVID-19 symptoms* | Fever | 582 (81.4%) | 144 (85.2%) | 0.245 | 475 (80.0%) | 247 (87.6%) | 0.006 |

| Cough | 603 (84.2%) | 135 (81.3%) | 0.364 | 497 (83.7%) | 234 (83.9%) | 0.940 | |

| Sore throat | 70 (12.0%) | 24 (17.1%) | 0.101 | 53 (10.7%) | 41 (18.1%) | 0.006 | |

| Runny nose | 26 (4.4%) | 12 (8.8%) | 0.041 | 27 (5.4%) | 11 (4.9%) | 0.781 | |

| Shortness of breath | 626 (86.7%) | 152 (88.9%) | 0.443 | 511 (86.3%) | 257 (88.3%) | 0.375 | |

| Loss of taste | 111 (19.8%) | 30 (21.7%) | 0.602 | 102 (21.1%) | 38 (17.9%) | 0.334 | |

| Loss of smell | 91 (16.1%) | 26 (19.3%) | 0.373 | 86 (17.8%) | 31 (14.5%) | 0.275 | |

| Headache | 128 (21.4%) | 37 (26.8%) | 0.170 | 103 (20.4%) | 59 (26.0%) | 0.094 | |

| Confusion | 89 (14.2%) | 25 (16.9%) | 0.400 | 74 (14.0%) | 41 (16.9%) | 0.306 | |

| Pre-admission medications | Immunosuppressant | 71 (10.5%) | 23 (14.5%) | 0.153 | 58 (10.3%) | 35 (13.3%) | 0.207 |

| Anti-infectives | 84 (12.3%) | 22 (14.1%) | 0.549 | 77 (13.6%) | 28 (10.6%) | 0.233 | |

| ACEI | 107 (15.8%) | 23 (14.2%) | 0.616 | 75 (13.3%) | 53 (19.9%) | 0.013 | |

| ARBS | 49 (7.3%) | 16 (10.0%) | 0.245 | 38 (6.7%) | 27 (10.2%) | 0.083 | |

| NSAID | 48 (7.2%) | 17 (11.0%) | 0.115 | 38 (6.8%) | 27 (10.6%) | 0.065 | |

| Respiratory support | Supplemental O2 | 708 (94.4%) | 172 (93.0%) | 0.460 | 576 (93.2%) | 295 (95.5%) | 0.199 |

| CPAP | 361 (50.3%) | 97 (56.4%) | 0.154 | 283 (47.5%) | 168 (59.2%) | 0.001 | |

| Bi-level NIV | 78 (11.4%) | 24 (14.6%) | 0.245 | 58 (10.2%) | 43 (15.7%) | 0.021 | |

| High flow nasal O2 | 306 (44.0%) | 61 (37.4%) | 0.125 | 244 (42.1%) | 119 (43.9%) | 0.627 | |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 319 (42.3%) | 103 (59.6%) | <0.001 | 223 (35.6%) | 201 (64.8%) | <0.001 | |

| ECMO | 24 (3.3%) | 9 (5.2%) | 0.242 | 22 (3.7%) | 11 (3.8%) | 0.925 | |

| Highest respiratory level | WHO class 3–4 | 40 (5.2%) | 11 (5.9%) | <0.001 | 39 (6.2%) | 12 (3.8%) | <0.001 |

| WHO class 5 | 142 (18.5%) | 28 (14.9%) | 132 (21.1%) | 36 (11.3%) | |||

| WHO class 6 | 260 (33.9%) | 39 (20.7%) | 227 (36.2%) | 68 (21.3%) | |||

| WHO class 7–9 | 325 (42.4%) | 110 (58.5%) | 229 (36.5%) | 203 (63.6%) | |||

| Treatments given | Antibiotic therapy | 644 (87.5%) | 167 (92.3%) | 0.079 | 521 (86.3%) | 282 (92.8%) | 0.005 |

| Systemic steroids | 452 (64.5%) | 89 (54.3%) | 0.014 | 368 (63.3%) | 167 (60.5%) | 0.406 | |

| Therapeutic dose anticoagulation | 396 (56.1%) | 93 (56.4%) | 0.949 | 320 (55.0%) | 164 (58.6%) | 0.320 | |

| Proning | 267 (39.9%) | 75 (49.0%) | 0.039 | 194 (34.9%) | 141 (54.4%) | <0.001 | |

| Renal replacement therapy | 75 (10.6%) | 21 (12.5%) | 0.473 | 58 (9.8%) | 37 (13.3%) | 0.132 | |

| Other diagnoses made during admission | PE/Microthrombi | 123 (17.0%) | 22 (12.8%) | 0.181 | 87 (14.5%) | 55 (19.1%) | 0.080 |

| Renal failure requiring dialysis | 60 (8.3%) | 20 (11.8%) | 0.155 | 44 (7.4%) | 35 (12.2%) | 0.013 | |

| Duration of stay | Median (IQR)† | 16 (9–33) | 24 (12–42.5) | <0.001 | 14 (8–28) | 28 (14–47) | <0.001 |

Unless otherwise specified, numbers are shown as counts (percentages) and p values have been calculated using χ2 test. Patients who had invasive mechanical ventilation were significantly more likely to report swallow and voice problems, likewise patients who were treated with systemic steroids and proning were significantly more likely to report swallow problems. Patients with swallow and voice problems had a significantly longer length of stay.

*The denominators vary for most variables, the number of excluded records due to missing data are recorded in online supplemental table S1.

†P value calculated using Kruskal-Wallis, p<0.05 are bolded.

ACEI, ACE inhibitors; ARBS, angiotensin II receptor blockers; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit; NIV, non-invasive ventilation; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Table 4.

Self-reported comorbidities recorded at baseline visit for those respondents who answered questions on voice or swallow problems

| ICU swallow | ICU voice | |||||

| No | Yes | P value | No | Yes | P value | |

| N (%) | 767 (80.3%) | 188 (19.7%) | 627 (66.3%) | 319 (33.7%) | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 34 (4.4%) | 6 (3.2%) | 0.446 | 25 (4.0%) | 15 (4.7%) | 0.605 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 46 (6.0%) | 14 (7.4%) | 0.463 | 37 (5.9%) | 22 (6.9%) | 0.549 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 33 (4.3%) | 10 (5.3%) | 0.547 | 30 (4.8%) | 13 (4.1%) | 0.620 |

| Hypertension | 298 (38.9%) | 65 (34.6%) | 0.279 | 236 (37.6%) | 124 (38.9%) | 0.712 |

| Congestive heart failure/Congenital heart disease/Valvular heard disease/Pacemaker/Implantable device/Peripheral vascular disease | 40 (5.2%) | 11 (5.9%) | 0.728 | 34 (5.4%) | 18 (5.6%) | 0.888 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia/Dyslipidaemia | 166 (21.6%) | 35 (18.6%) | 0.362 | 138 (22.0%) | 62 (19.4%) | 0.359 |

| Cerebrovascular accident/Transient ischaemic attack | 42 (5.5%) | 8 (4.3%) | 0.501 | 33 (5.3%) | 17 (5.3%) | 0.966 |

| Depression or anxiety | 103 (13.4%) | 41 (21.8%) | 0.004 | 86 (13.7%) | 56 (17.6%) | 0.118 |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic pain | 37 (4.8%) | 19 (10.1%) | 0.006 | 32 (5.1%) | 24 (7.5%) | 0.136 |

| Any previous treatment with antidepressant medication | 81 (10.6%) | 40 (21.3%) | <0.001 | 78 (12.4%) | 40 (12.5%) | 0.965 |

| Any previous treatment by a mental health professional for a mental health problem | 33 (4.3%) | 21 (11.2%) | <0.001 | 25 (4.0%) | 27 (8.5%) | 0.004 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 32 (4.2%) | 8 (4.3%) | 0.959 | 27 (4.3%) | 12 (3.8%) | 0.690 |

| Asthma | 126 (16.4%) | 49 (26.1%) | 0.002 | 96 (15.3%) | 74 (23.2%) | 0.003 |

| Obstructive sleep apnoea | 39 (5.1%) | 14 (7.4%) | 0.205 | 35 (5.6%) | 18 (5.6%) | 0.969 |

| Interstitial lung disease/Bronchiectasis/Obesity hypoventilation syndrome/Pleural effusion | * | * | * | 14 (2.2%) | 11 (3.4%) | 0.271 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | * | * | * | 20 (3.2%) | 9 (2.8%) | 0.756 |

| Osteoarthritis | 75 (9.8%) | 21 (11.2%) | 0.570 | 57 (9.1%) | 38 (11.9%) | 0.172 |

| Peptic ulcer disease/Liver disease | 41 (5.3%) | 6 (3.2%) | 0.221 | 34 (5.4%) | 13 (4.1%) | 0.367 |

| Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease | 62 (8.1%) | 29 (15.4%) | 0.002 | 52 (8.3%) | 39 (12.2%) | 0.052 |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 21 (2.7%) | 9 (4.8%) | 0.149 | 14 (2.2%) | 16 (5.0%) | 0.021 |

| Diabetes | 186 (24.3%) | 45 (23.9%) | 0.928 | 151 (24.1%) | 77 (24.1%) | 0.985 |

| Hypothyroidism | 38 (5.0%) | 9 (4.8%) | 0.924 | 30 (4.8%) | 17 (5.3%) | 0.716 |

| Chronic kidney disease (any stage) | 43 (5.6%) | 7 (3.7%) | 0.299 | 39 (6.2%) | 11 (3.4%) | 0.072 |

| Cancer | 58 (7.6%) | 9 (4.8%) | 0.182 | 44 (7.0%) | 23 (7.2%) | 0.913 |

| Infectious disease | * | * | * | 11 (1.8%) | 8 (2.5%) | 0.435 |

| Number of comorbidities | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.528 | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.171 |

Unless otherwise specified, numbers are shown as counts (percentages) and p values have been calculated using χ2 test.

*Numbers ≤5 have been suppressed, p<0.05 are bolded. Patients reporting asthma, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, depression, chronic fatigue syndrome and previous treatments for a mental health problem were significantly more likely to report a swallow problem, likewise patients reporting irritable bowel syndrome, asthma and previous treatment by a mental health professional were more likely to report voice problems.

ICU, intensive care unit.

bmjresp-2023-001647supp001.pdf (445.7KB, pdf)

Respondents with swallow problems spent longer in hospital (median length of stay: 24 vs 16 days) and were more likely to report worsening mobility (p<0.001), self-care (p<0.001), usual activities (p=0.005), pain or discomfort (p=0.006) and have lower health score (p<0.001) (table 5). They had a higher overall score on the Dyspnoea 12 (p<0.001), and on physical and affective subdomains (p<0.001), had a higher PCL-5 (PTSD) overall score (p<0.001) and were more likely to be clinically frail according to the RCF (p<0.001) (table 5). Swallow problems were only collected at one time point so it is not possible to determine how long these problems persisted. Variables included in the final model chosen by cross-validation are detailed in online supplemental data 1.1.

Table 5.

Outcomes for respondents who stated they had voice or swallow problems

| ICU swallow—visit 1* | ICU swallow—visit 2* | ICU voice—visit 1* | ICU voice—visit 2* | ||||||||||

| No | Yes | P value | No | Yes | P value | No | Yes | P value | No | Yes | P value | ||

| EQ-5D-5L | |||||||||||||

| Mobility | Improved | 30 (5.9%) | 9 (6.5%) | <0.001 | 34 (7.5%) | 7 (6.4%) | 25 (6.1%) | 14 (6.0%) | 25 (7.1%) | 16 (7.7%) | |||

| Stayed the same | 300 (58.8%) | 54 (38.8%) | 269 (59.5%) | 42 (38.5%) | <0.001 | 247 (60.5%) | 104 (44.4%) | <0.001 | 217 (61.8%) | 93 (44.9%) | <0.001 | ||

| Worsened | 180 (35.3%) | 76 (54.7%) | 149 (33.0%) | 60 (55.0%) | 136 (33.3%) | 116 (49.6%) | 109 (31.1%) | 98 (47.3%) | |||||

| Self-care | Improved/Stayed the same | 270 (52.9%) | 51 (36.7%) | <0.001 | 262 (57.8%) | 39 (35.8%) | <0.001 | 228 (55.7%) | 90 (38.6%) | <0.001 | 213 (60.5%) | 86 (41.5%) | <0.001 |

| Worsened | 240 (47.1%) | 88 (63.3%) | 191 (42.2%) | 70 (64.2%) | 181 (44.3%) | 143 (61.4%) | 139 (39.5%) | 121 (58.5%) | |||||

| Usual activities | Improved | 20 (3.9%) | 7 (5.0%) | 0.005 | 24 (5.3%) | 7 (6.4%) | 20 (4.9%) | 7 (3.0%) | 19 (5.4%) | 11 (5.3%) | |||

| Stayed the same | 274 (53.7%) | 53 (38.1%) | 259 (57.2%) | 37 (33.9%) | <0.001 | 231 (56.5%) | 91 (39.1%) | <0.001 | 208 (59.1%) | 86 (41.5%) | <0.001 | ||

| Worsened | 216 (42.4%) | 79 (56.8%) | 170 (37.5%) | 65 (59.6%) | 158 (38.6%) | 133 (57.1%) | 125 (35.5%) | 110 (53.1%) | |||||

| Pain/Discomfort | Improved | 99 (19.4%) | 22 (15.8%) | 0.006 | 98 (21.6%) | 22 (20.2%) | 82 (20.1%) | 39 (16.7%) | 78 (22.2%) | 40 (19.3%) | |||

| Stayed the same | 246 (48.3%) | 52 (37.4%) | 226 (49.9%) | 35 (32.1%) | <0.001 | 200 (49.0%) | 94 (40.3%) | 0.009 | 177 (50.3%) | 83 (40.1%) | 0.006 | ||

| Worsened | 164 (32.2%) | 65 (46.8%) | 129 (28.5%) | 52 (47.7%) | 126 (30.9%) | 100 (42.9%) | 97 (27.6%) | 84 (40.6%) | |||||

| Anxiety /Depression | Improved | 68 (13.4%) | 8 (5.8%) | 0.001 | 60 (13.3%) | 11 (10.1%) | 52 (12.7%) | 24 (10.3%) | 50 (14.2%) | 21 (10.2%) | |||

| Stayed the same | 242 (47.5%) | 53 (38.1%) | 229 (50.7%) | 40 (36.7%) | 0.004 | 203 (49.6%) | 89 (38.4%) | 0.004 | 177 (50.3%) | 89 (43.2%) | 0.030 | ||

| Worsened | 199 (39.1%) | 78 (56.1%) | 163 (36.1%) | 58 (53.2%) | 154 (37.7%) | 119 (51.3%) | 125 (35.5%) | 96 (46.6%) | |||||

| Summary—How good or bad is your health overall? | Current scoreˣ | 75 (60–85) | 64 (50–80) | <0.001 | 80 (60–90) | 60 (50–80) | <0.001 | 79 (60–86) | 65 (50–80) | <0.001 | 80 (60–90) | 70 (50–80) | <0.001 |

| Improved | 67 (13.6%) | 14 (10.7%) | 0.152 | 80 (18.3%) | 14 (13.9%) | 54 (13.6%) | 26 (11.8%) | 62 (18.3%) | 32 (16.3%) | ||||

| Stayed the same | 109 (22.1%) | 21 (16.0%) | 74 (16.9%) | 13 (12.9%) | 0.264 | 100 (25.2%) | 29 (13.2%) | 0.001 | 64 (18.9%) | 23 (11.7%) | 0.057 | ||

| Worsened | 317 (64.3%) | 96 (73.3%) | 283 (64.8%) | 74 (73.3%) | 243 (61.2%) | 165 (75.0%) | 213 (62.8%) | 141 (71.9%) | |||||

| MRC Dyspnoea Scale | Improved/Stayed the same | 110 (43.8%) | 28 (33.7%) | 0.106 | 53 (57.0%) | 19 (51.4%) | 0.560 | 86 (44.1%) | 50 (37.0%) | 0.207 | 45 (61.6%) | 27 (47.4%) | 0.104 |

| Worsened | 141 (56.2%) | 55 (66.3%) | 40 (43.0%) | 18 (48.6%) | 109 (55.9%) | 85 (63.0%) | 28 (38.4%) | 30 (52.6%) | |||||

| Dyspnoea 12‡ | Overall score | 3 (0–9) | 8 (2–19) | <0.001 | 2 (0–7) | 8 (1–18) | <0.001 | 2 (0–8) | 6 (1–15) | <0.001 | 1 (0–6) | 5 (1–15) | <0.001 |

| Physical domain | 2 (0–7) | 6 (2–12) | <0.001 | 2 (0–6) | 6 (1–11) | <0.001 | 2 (0–6) | 4 (1–10) | <0.001 | 1 (0–5) | 4 (1–10) | <0.001 | |

| Affective domain | 0 (0–2) | 1.5 (0–7) | <0.001 | 0 (0–1) | 2 (0–6) | <0.001 | 0 (0–1) | 1 (0–5) | <0.001 | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–5) | <0.001 | |

| PCL-5 | Overall scoreˣ | 9 (3–24) | 25 (8–41.5) | <0.001 | 7 (2–21) | 19.5 (7–42) | <0.001 | 7 (2–21) | 20 (7–39) | <0.001 | 6 (1–19) | 15 (5–38) | <0.001 |

| Overall score >32 | 107 (16.0%) | 65 (36.1%) | <0.001 | 79 (11.8%) | 48 (26.4%) | <0.001 | 78 (14.6%) | 91 (29.7%) | <0.001 | 54 (10.0%) | 71 (23.1%) | <0.001 | |

| MoCA§ | Overall scoreˣ | 26.5 (24–28) | 26 (23–28) | 0.306 | 27 (25–29) | 27 (25–29) | 0.439 | 26 (24–28) | 27 (24–28) | 0.757 | 27 (25–29) | 27 (25–29) | 0.612 |

| Normal function | 346 (61.1%) | 78 (53.8%) | 0.071 | 337 (69.8%) | 81 (66.4%) | 0.471 | 275 (59.5%) | 143 (59.6%) | 0.937 | 267 (69.2%) | 149 (69.3%) | ||

| Mild impairment | 204 (36.0%) | 58 (40.0%) | 146 (30.2%) | 41 (33.6%) | 172 (37.2%) | 88 (36.7%) | 109 (28.2%) | 59 (27.4%) | 0.884 | ||||

| Moderate/Severe impairment | 16 (2.8%) | 9 (6.2%) | 15 (3.2%) | 9 (3.8%) | 10 (2.6%) | 7 (3.3%) | |||||||

| RCF¶ | Frail | 41 (6.3%) | 23 (14.6%) | <0.001 | 22 (3.9%) | 21 (15.2%) | <0.001 | 27 (5.1%) | 36 (13.5%) | <0.001 | 19 (4.2%) | 23 (9.1%) | 0.009 |

Outcomes taken from the same visit as reported visit or swallow problems. Unless otherwise specified, numbers are reported as count (percentage) and p values are the result of a χ2 test. P<0.05 are bolded.

*The denominators vary for most variables, the number of excluded records due to missing data are recorded in online supplemental table S1.

‡Values are shown as median (IQR) and Kruskal-Wallis test is used.

§Normal cognitive function score >25, mild cognitive impairment score 18–25, moderate or severe cognitive impairment score <18.

¶Frail defined as RCF ≥5.

ICU, intensive care unit; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PCL-5, Post-traumatic Checklist for DSM-5; RCF, Rockwood Clinical Frailty.

Voice problems

Over a third of eligible respondents reported voice problems (319/946, 34%) during their admission. There were no demographic differences between participants with and without voice problems (table 1); however, they were more likely to have asthma (23% vs 15%, p=0.003) to have received CPAP (59% vs 47%, p=0.001), NIV (16% vs 10%, p=0.021) and almost twice as likely to have received IMV (65% vs 36%) (table 3). These are important associations which identify relationships between perceived voice problems and respiratory compromise. They were also more likely to receive antibiotics (93% vs 86%), to have been proned (54% vs 35%) and to have a new diagnosis of renal failure requiring dialysis (12% vs 7%). They were more likely to state one of their COVID-19 symptoms was a fever (88% vs 80%) and to have experienced a sore throat (18% vs 11%) than those without (table 3).

Respondents with voice problems spent on average 2 weeks longer in hospital than those without (median length of stay: 28 vs 14 days) and were more likely to report a worsening of their mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, anxiety or depression and have a lower health score (table 5). They had a higher overall score on the Dyspnoea 12 questionnaire (both physical and affective), had a higher PCL-5 overall score and were more likely to be classified as clinically frail. Variables included in the final model chosen by cross-validation are detailed in online supplemental data 1.2. Voice problems were only collected at one time point so it is not possible to comment on how long these problems lasted.

Communication issues

Visit 1

Approximately one in four experienced communication issues at visit 1 (527/2375, 23%), they were younger (median: 56 vs 60 years), a higher proportion were female (48% vs 36%), came from more deprived areas (27% vs 22%), were healthcare workers (17% vs 13%) and had been shielding prior to admission (34% vs 28%) (table 2). This is important clinical information, identifying those who recognised deterioration in their ability to communicate. They were more likely to report COVID-19 symptoms; fever (81% vs 77%, p=0.023), shortness of breath (88% vs 83%, p=0.014), sore throat (19% vs 13% p=0.003) and confusion (18% vs 11 %, p=0.001) (online supplemental table 6). They reported worse; mobility (51% vs 29%), self-care (64% vs 40%), usual activities (57% vs 35%), pain or discomfort (40% vs 25%) anxiety or depression (49% vs 35%) on the EQ-5D-5L, and worse overall health (online supplemental table 7) than pre-COVID-19. Their MRC Dyspnoea Scale was also worse (61% vs 50%) and they had higher Dyspnoea 12 (9 vs 2) scores, PCL-5 (25 vs 7), with more classed as frail (12% vs 4%). Respondents were also more likely to have mild cognitive impairment (42% vs 34%) or moderate/severe impairment (4% vs 3%) according to the MoCA. Variables included in the final model chosen by cross-validation are detailed in online supplemental data 1.3.

Visit 2

Just under one in four identified as having communication issues (n=399/1771, 23%), they were more likely to have been admitted to ICU (42% vs 36%), and to report headache (33% vs 26%) or sore throat (20% vs 14%) as COVID-19 symptoms (online supplemental table 6). They had significantly worse outcomes, with the exception of MoCA where there did not appear to be a significant difference (online supplemental table 7). Variables included in the final model chosen by cross-validation are detailed in online supplemental data 1.4

Cognitive issues

Visit 1

Over two-thirds reported cognitive issues at visit 1 (n=1598/2275, 70%) and were more likely to have been female (44% vs 27%), white (78% vs 68%), not educated beyond secondary school level (32% vs 25%) to have been shielding (32% vs 24%), to have more comorbidities at baseline (online supplemental table 8) median: 2 vs 1, but with no difference in age (table 2). There were no significant difference in treatments, respiratory support, additional diagnoses, admission to ICU nor the overall length of stay between respondents who did or did not state they had cognitive issues except those with cognitive issues at visit 2 were more likely to have received NIV (6% vs 3%).

Respondents with cognitive issues were more likely to report worsening mobility (42% vs 16%), self-care (56% vs 23%), usual activities (49% vs 20%), pain or discomfort (35% vs 13%), anxiety or depression (46% vs 20%), overall health (65% vs 52%) and MRC Dyspnoea Scale (58% vs 37%) compared with pre-COVID-19. The Dyspnoea 12 overall score was significantly higher for respondents with cognitive issues (median: 5 vs 0), as was the PCL-5 summary score (median 14 vs 3). There were slightly more respondents with self-reported cognitive issues classified as having moderate or severe cognitive impairment on the MoCA (4% vs 2%) and were significantly more likely to have been deemed clinically frail at the follow-up visit (8% vs 2%). Variables included in the final model chosen by cross-validation are detailed in online supplemental data 1.5.

Visit 2

A similar proportion of respondents self-reported cognitive issues at visit 2 (1231/1768, 70%), more likely to be female (43% vs 26%), white (80% vs 71%), shielding (32% vs 25%) and to have come from a more deprived area (Q1 24% vs 19%) (table 2). Significantly more respondents with cognitive issues at visit 2 were treated via CPAP (29% vs 24%) and had longer length of stay (8 vs 7 days). As with respondents who identified as having cognitive issues at visit 1, worsening in mobility (38% vs 14%), self-care (53% vs 20%), usual activities (46% vs 18%), pain or discomfort (33% vs 13%) and anxiety or depression (44% vs 18%) and overall worsening in their health (67% vs 50%) were identified (online supplemental table 8). They were also more likely to have worsening in breathing according to the MRC Dyspnoea Scale (49% vs 23%) and Dyspnoea 12 (4 vs 0), and more respondents were classed as frail (7% vs 1%). Significantly fewer respondents were classified as having normal cognitive function according to the MoCA (68% vs 75%). Variables included in the final model chosen by cross-validation are detailed in online supplemental data 1.6.

Discussion

This is the first large-scale prospective analysis of swallowing, communication, voice and cognitive function following hospitalisation with COVID-19 in the UK, with prevalent and persistent compromise identified. These data raise important questions about management and potential rehabilitation requirements for those individuals with complex symptoms and their recovery.

Swallow compromise following an ICU stay was associated with variables inherently linked to increased illness severity and treatment burden, specifically proning and mechanical ventilation, rather than pre-existing factors such as sociodemographics or number of comorbidities. This is reported in critical illness data predating COVID-19 and may reflect iatrogenic impact of ventilation on the upper airway,7 21 35–37 reiterating the importance of identification of swallow and voice problems and their aetiology post-ICU admission, to facilitate differential diagnosis and rehabilitation to improve function and positively influence bed stay.38 Patients with swallow/voice problems stayed in hospital over a week and 2 weeks longer than those without, respectively. They also had resultant frailty, poor mobility and worse quality of life scores.

Associations between swallow/voice symptoms and previous mental health problems were identified. Concurrent mental and physical health compromise are complex and costly for the individual, and for the economy if left untreated. Conservative estimates suggest39 poor mental health costing the UK economy £74–94 billion a year as a result of lost output. Given our findings regarding associations with physiological symptoms and mental health, devising interventions where the whole person and their symptoms are supported and rehabilitated must be prioritised.40 The ‘unknown illness’ of the pandemic, insufficient ‘medical spaces’41 and until now, under-recognised symptomatology described in this paper require urgent and collective attention from clinicians and commissioners to reduce physical, emotional and economic burden.

Nearly one in four participants reported communication issues at visits 1 and 2, with worse mobility, self-care, pain, anxiety or depression and overall health scores compared with pre-COVID-19. These people were more likely to be younger, female, health workers, from areas of social deprivation and have cognitive compromise. These are concerning conglomerate issues, with overt self-limiting realities regarding the ability to self-manage and seek support when cognition and communication skills are compromised. Early diagnosis and assessment may be challenged by this unusual profile or presentation for an individual reporting communication issues, so healthcare professionals may overlook this symptom in a clinical setting. The mechanism of injury, rehabilitation needs and recovery trajectory is not yet understood and future studies require detailed culturally appropriate assessments to fully uncover language pathology to determine appropriate, effective treatment interventions.

There are conflicting perspectives regarding associations between compromised cognition following COVID-1915 42 with severity of disease,43 44 severity of respiratory compromise45 and being female46 reported as independent variables by some groups, with others not identifying these relationships.47 48 Methodological variation and limitations of existing outcome measures are important factors to consider when comparing findings, along with the novel nature of this disease, reiterating the importance of creating core datasets.49 In our analysis, associations between worse self-reported cognition and social deprivation at visit 2 were identified. In the context of public health, social deprivation is linked to worse global health outcomes and mortality50 51 and is of practical importance when considering health literacy, access to health services and the individual’s ability to broadly navigate health systems to support their own recovery, perhaps without the appropriate tools or facilities.52 In context of the UK health system, finding solutions to these problems is challenged by conglomerate social and political drivers affecting identification, management and implementation of all health interventions. We offer suggestions from the insights generated in this analysis, while acknowledging the healthcare landscape and its realities.

Strengths and limitations

This analysis was not set-up as a formal prevalence study. There is acquisition bias in the cohort and therefore we can only report what is observed in the study rather than assuming this is representative of the wider population. We have not reported on incidence, the frequency or rate of occurrence of new self-reported functional compromise, as we sought to explore all cases reported in the time frame and their persistence over a specific time frame. Notwithstanding this limitation, it is the biggest study to date and therefore a rich dataset and a valuable observation. For the first time, we have been able to detail the prevalence of self-reported swallow, communication, voice and cognitive symptoms, defining associations and independent variables which may influence these outcomes. Triangulating these findings with intelligence around clinical provision will support understanding around how to design and commission services to support patients experiencing these issues.

Limitations include the following: only people admitted to ICU were asked to report on their swallowing and voice. We could therefore only report on this subgroup, and so are likely to be over-representing the prevalence but under-representing the total burden. In addition, lack of detail within the communication and swallow assessments means we are able to report on overall (self-reported) symptoms only. Direct laryngoscopy and assessment of swallow was not undertaken. We do not have the fine-grained information on swallow, or communication compromise required to identify what specific aspects of swallow, speech, language and/or communication have been impacted (and how), or if these were pre-existing and/or exacerbated. Data were collected over the first year post hospitalisation, but not beyond that point, so we do not yet know how these symptoms progress or change over time. Similarly, some data points, such as BMI, were only collected at visit 1 so comparisons of index scores cannot be made between visits. Missing data, as described in the ‘Methods’ section, is an important limitation of this study.

Conclusion

This is the first study to explore prevalence of swallow, communication, voice and cognitive issues post hospitalisation with COVID-19. These data are fundamental to identify and understand the complex functional compromise people experienced, and to determine what future interventions are required to reduce the burden of these symptoms. The individuals with greatest functional compromise were frequently those who had been most acutely unwell, women, from areas of social deprivation. We recommend; ring-fenced research funding to identify mechanism of injury and rehabilitation requirements, culturally appropriate communication and swallowing assessments to help understand the impact on the individual rehabilitation required and trajectories of recovery and access to dedicated swallow, communication, voice and cognitive evaluation within long COVID clinics.

Swallow, voice, communication and cognition are the cornerstones of human interaction and existence. Their compromise following COVID-19 has significant and far-reaching potential impact on the individual, their communities and the economy. There is a time-specific opportunity to research these challenges, to provide practical approaches to help people improve these key functions.

Acknowledgments

This study would not be possible without all the participants who have given their time and support. We thank all the participants and their families. We thank the many research administrators, healthcare and social care professionals who contributed to setting up and delivering the study at all of the 65 NHS Trusts/Health boards and 25 research institutions across the UK, as well as all the supporting staff at the NIHR Clinical Research Network, Health Research Authority, Research Ethics Committee, Department of Health and Social Care, Public Health Scotland and Public Health England, and support from the ISARIC Coronavirus Clinical Characterisation Consortium. We thank Kate Holmes at the NIHR Office for Clinical Research Infrastructure (NOCRI) for her support in coordinating the charities group. The PHOSP-COVID industry framework was formed to provide advice and support in commercial discussions, and we thank the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry as well NOCRI for coordinating this. We are very grateful to all the charities that have provided insight to the study: Action Pulmonary Fibrosis, Alzheimer’s Research UK, Asthma + Lung UK, British Heart Foundation, Diabetes UK, Cystic Fibrosis Trust, Kidney Research UK, MQ Mental Health, Muscular Dystrophy UK, Stroke Association Blood Cancer UK, McPin Foundations and Versus Arthritis. We thank the NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre patient and public involvement group and Long COVID Support.

Footnotes

Twitter: @camillacdawson, @alexrhorsley

Contributors: CD wrote the manuscript in collaboration with GC, FE, SW, AK, NS and SD. MC and AK conceptualised and formalised the data access. FE undertook the statistical analysis. DGW, CB, WM, SS, ED, JSa, MMcN, TC, MR, CEB, NJG, LVW, OCL, ARH, RMS, JKQ, L-PH, MM, JW, NH, NIL, RAE and HMcA all reviewed and provided updates and iterations to the drafting of the manuscript. CD is responsible for overall content as guarantor.The guarantor accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish. The PHOSP collaboration all supported data collection.

Funding: PHOSP-COVID is jointly funded by a grant from the MRC-UK Research and Innovation and the Department of Health and Social Care through the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) rapid response panel to tackle COVID-19 (grant references: MR/V027859/1 and COV0319).

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Health Service (NHS), the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists provided funding for the statistician support.

Competing interests: CEB has a UKRI PHOSP grant through NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre for support to conduct the PHOSP study, and Nottingham Hospital Trust Charity donations to support her research. JC has grants/contracts with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Insmed, Gilead Sciences, Grifols and has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Insmed, Gilead Sciences, Grifols, Pfizer, Zambon, Antabio, Janssen. LVW holds a UK Research and Innovation GSK/Asthma + Lung UK National Institute of Health Research Grant and Orion Pharma GSK Genentech AstraZeneca research funding and has received consulting fees from Galapagos Boehringer Ingelheim and travel fees from Greentech, is on the advisory board for Galapagos and is the Associate Editor for European Respiratory Journal. MR has received consulting fees from Galapagos Boehringer Ingelheim. ASi received joint funding UKRI & NIHR grant references: MR/V027859/1 and COV031. CB has received UKRI/DHSC PHOSP-COVID grant via NIHR Leicester BRC, grants from GSK, AZ, Sanofi, BI, Chiesi, Novartis, Roche, Genentech, Mologic, 4DPharma, consultancy paid to institution from GSK, AZ, Sanofi, BI, Chiesi, Novartis, Roche, Genentech, Mologic, 4DPharma, TEVA. RAE has received NIHR/UKRI/Wolfson Foundation grants, consulting fees from AstraZeneca for long COVID, honoraria payment from Boeringher, support from Chiesi to attend BTS, and is ERS Group 01.02 Pulmonary Rehabilitation Secretary. JKQ is on the Thorax editorial board.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the 'Methods' section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study was reviewed by the Yorkshire & Humber-Leeds West Research Ethics Committee (ethics reference: 20/YH/0225, IRAS Project ID: 285439). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Chevinsky JR, Tao G, Lavery AM, et al. Late conditions diagnosed 1–4 months following an initial Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) encounter: a matched-cohort study using inpatient and outpatient administrative data—United States. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73:S5–16.:ciab338. 10.1093/cid/ciab338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F, et al. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA 2020;324:603–5. 10.1001/jama.2020.12603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, et al. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA 2020;324:782. 10.1001/jama.2020.12839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelosi P, Tonelli R, Torregiani C, et al. Different methods to improve the monitoring of noninvasive respiratory support of patients with severe pneumonia/ARDS due to COVID-19: an update. JCM 2022;11:1704. 10.3390/jcm11061704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NICE . COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19 NICE guideline. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans RA, McAuley H, Harrison EM, et al. Physical, cognitive, and mental health impacts of COVID-19 after hospitalisation (PHOSP-COVID): a UK multicentre, prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2021;9:1275–87. 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00383-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dawson C, Nankivell P, Pracy JP, et al. Functional laryngeal assessment in patients with tracheostomy following COVID-19 a prospective cohort study. Dysphagia 2023;38:657–66. 10.1007/s00455-022-10496-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawson C, Capewell R, Ellis S, et al. Dysphagia presentation and management following COVID-19: an acute care tertiary centre experience. J Laryngol Otol 2020;2020:1–6. 10.1017/S0022215120002443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Argenziano MG, Bruce SL, Slater CL, et al. Characterization and clinical course of 1000 patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 in New York: retrospective case series. BMJ 2020;369:m1996. 10.1136/bmj.m1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with COVID-19 using the ISARIC WHO clinical characterisation protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ 2020;369:m1985. 10.1136/bmj.m1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin-Harris B. Clinical implications of respiratory-swallowing interactions. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008;16:194–9. 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3282febd4b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marik PE. Aspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2001;344:665–71. 10.1056/NEJM200103013440908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellis C, Urban S. Age and Aphasia: a review of presence, type, recovery and clinical outcomes. Top Stroke Rehabil 2016;23:430–9. 10.1080/10749357.2016.1150412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jennings G, Monaghan A, Xue F, et al. Comprehensive clinical characterisation of brain fog in adults reporting long COVID symptoms. J Clin Med 2022;11:3440. 10.3390/jcm11123440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hampshire A, Trender W, Chamberlain SR, et al. Cognitive deficits in people who have recovered from COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine 2021;39:101044. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carson G, Long Covid Forum Group . Research priorities for long Covid: refined through an international multi-stakeholder forum. BMC Med 2021;19:84. 10.1186/s12916-021-01947-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitworth A, Webster J, Howard D. A cognitive neuropsychological approach to assessment and intervention in Aphasia. In: A cognitive neuropsychological approach to assessment and intervention in aphasia: a clinician’s guide. Psychology Press, 2014. 10.4324/9781315852447 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Worrall L, Sherratt S, Rogers P, et al. What people with aphasia want: their goals according to the ICF. Aphasiology 2011;25:309–22. 10.1080/02687038.2010.508530 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halpin SJ, McIvor C, Whyatt G, et al. Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID‐19 infection: a cross‐sectional evaluation. J Med Virol 2021;93:1013–22. 10.1002/jmv.26368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cantarella G, Aldè M, Consonni D, et al. Prevalence of dysphonia in non hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Lombardy, the Italian epicenter of the pandemic. J Voice 2021:S0892-1997(21)00108-9. 10.1016/j.jvoice.2021.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brodsky MB, Levy MJ, Jedlanek E, et al. Laryngeal injury and upper airway symptoms after oral endotracheal intubation with mechanical ventilation during critical care: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 2018;46:2010–7. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Podesva RJ, Callier P. Voice quality and identity. Ann Rev Appl Linguist 2015;35:173–94. 10.1017/S0267190514000270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Misono S, Marmor S, Yueh B, et al. Treatment and survival in 10,429 patients with localized Laryngeal cancer: a population-based analysis. Cancer 2014;120:1810–7. 10.1002/cncr.28608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vilkman E. Voice problems at work: a challenge for occupational safety and health arrangement. Folia Phoniatr Logop 2000;52:120–5. 10.1159/000021519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:W163–94. 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010-w1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loney PL, Chambers LW, Bennett KJ, et al. Critical appraisal of the health research literature: prevalence or incidence of a health problem. Chronic Dis Can 1998;19:170–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727–36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fletcher C. Standardised questionnaire on respiratory symptoms. BMJ 1960;2:1665. 10.1136/bmj.2.5213.166513688719 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yorke J, Moosavi SH, Shuldham C, et al. Quantification of dyspnoea using descriptors: development and initial testing of the Dyspnoea-12. Thorax 2010;65:21–6. 10.1136/thx.2009.118521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, et al. The Posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM‐5 (PCL‐5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress 2015;28:489–98. 10.1002/jts.22059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:695–9. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005;173:489–95. 10.1503/cmaj.050051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.UK Government . English indices of deprivation 2019: technical report. Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, 2019. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.%20gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/835115/IoD2019_Statistical_Release.%20pdf [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sura L, Madhavan A, Carnaby G, et al. Dysphagia in the elderly: management and nutritional considerations. Clin Interv Aging 2012;7:287–98. 10.2147/CIA.S23404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miu K, Miller B, Tornari C, et al. 263 airway, voice and swallow outcomes following endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation for COVID-19 pneumonitis: preliminary results of a prospective cohort study. Br J Surg 2021;108:znab134.049. 10.1093/bjs/znab134.049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boggiano S, Williams T, Gill SE, et al. Multidisciplinary management of laryngeal pathology identified in patients with COVID-19 following Trans-Laryngeal intubation and Tracheostomy. J Intensive Care Soc 2022;23:425–32. 10.1177/17511437211034699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skoretz SA, Flowers HL, Martino R. The incidence of dysphagia following endotracheal intubation: a systematic review. Chest 2010;137:665–73. 10.1378/chest.09-1823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lerner AM, Robinson DA, Yang L, et al. Toward understanding COVID-19 recovery: National Institutes of health workshop on Postacute COVID-19. Ann Intern Med 2021;174:999–1003. 10.7326/M21-1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stevenson D, Farmer P. Thriving at work: the Stevenson/Farmer review of mental health and employers. London: Department for Work and Pensions and Department of Health, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naylor C, Parsonage M, McDaid D, et al. Long-term conditions and mental health: the cost of co-morbidities. London: King’s Fund, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Philip KEJ, Owles H, McVey S, et al. An online breathing and wellbeing programme (ENO breathe) for people with persistent symptoms following COVID-19: a parallel-group, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2022;10:851–62. 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00125-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henneghan AM, Lewis KA, Gill E, et al. Cognitive impairment in non-critical, mild-to-moderate COVID-19 survivors. Front Psychol 2022;13:770459. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.770459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferrucci R, Dini M, Groppo E, et al. Long-lasting cognitive abnormalities after COVID-19. Brain Sci 2021;11:235. 10.3390/brainsci11020235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Becker JH, Lin JJ, Doernberg M, et al. Assessment of cognitive function in patients after COVID-19 infection. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2130645. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.30645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miskowiak KW, Johnsen S, Sattler SM, et al. Cognitive impairments four months after COVID-19 hospital discharge: pattern, severity and association with illness variables. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2021;46:39–48. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mazza MG, Palladini M, De Lorenzo R, et al. Persistent psychopathology and neurocognitive impairment in COVID-19 survivors: effect of inflammatory biomarkers at three-month follow-up. Brain Behav Immun 2021;94:138–47. 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.02.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramani C, Davis EM, Kim JS, et al. Post-ICU COVID-19 outcomes: a case series. Chest 2021;159:215–8. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.08.2056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raman B, Cassar MP, Tunnicliffe EM, et al. Medium-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on multiple vital organs, exercise capacity, cognition, quality of life and mental health, post-hospital discharge. EClinicalMedicine 2021;31:100683. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munblit D, Nicholson TR, Needham DM, et al. Studying the post-COVID-19 condition: research challenges, strategies, and importance of core outcome set development. BMC Med 2022;20:50. 10.1186/s12916-021-02222-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eibner C, Evans WN. Relative deprivation, poor health habits, and mortality. J Human Resources 2005;XL:591–620. 10.3368/jhr.XL.3.591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carstairs V, Morris R. Deprivation and health in Scotland. Health Bull (Edinb) 1990;48:162–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Howard DH, Sentell T, Gazmararian JA. Impact of health literacy on socioeconomic and racial differences in health in an elderly population. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:857–61. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00530.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjresp-2023-001647supp001.pdf (445.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.