Abstract

Vapor-phase molecular simulation studies of aromatic compounds with five or more fluorine atoms on the ring reveal emission spectra characterized by S0 → πσ* and πσ*→S0 transitions. In this study, the absorption, excitation, and solvent-dependent emission spectra of fluorinated benzenes, including pentaflurophenyalanine (F5Phe), which is a potential marker for biochemical research, were collected and compared to the results of the simulation. Time-dependent self-consistent field (TD-SCF) density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to examine the nature of excited states and relevant photo-physical processes. The results show that pentafluorobenzene (PFB) and hexafluorobenzene (HFB) show behavior consistent with the vapor phase simulation studies, that tracts well with benzenes substituted with fewer fluorine atoms. For example, 1,2,3-trifluorobenzene (123TFB) and 1,2,3,4-tetrafluorobenzene (1234TFB) show emission spectra with varying intensities of tails and shoulders. Those features are attributed to πσ*→S0 transitions where the πσ* state has been stabilized in the presence of solvents like water, acetonitrile, and isopropanol, which are different from their simulated behavior in the gas phase. The emission in water solvent especially shows a significant increase in the emission intensity at 310 nm, which is common for all studied samples. The emission spectrum of F5Phe closely reflects that of PFB, which arises from the interplay of both ππ *→S0 and πσ*→S0 transitions. Also, it is observed that the interaction between adjacent σ* orbitals of C-F bond for 123-TFB, 1234-TFB, 12345-PFB, and 123456-HFB contributes to further narrowing the energy gap between S0 and S1 states with a significant red shift on the emission spectra compared to their isomers.

1. Introduction

Aromatic rings are found in natural compounds like amino acids and DNA bases as key building blocks with essential roles. Aromatic rings are commonly adapted in a significant portion of modern medicine [1]. Aromatic molecules with high degree of resonance stability and rigid structure are expected to fluoresce strongly, thus they are useful for biological research as a sensor or imaging agent [2]. Moreover, introducing halogens on the aromatic rings opened the door to diverse fields like material science, pharmaceutics, and medicinal sciences. In addition to the rich study of drug design [3] with fluorination, emulsions of fluorinated oils with water have expanded the application of fluorine to biomedical imaging and drug delivery [2]. Additionally fluorinated compounds also exhibit improved membrane permeability and pharmacokinetic properties due to stability in metabolism [4]. Another interesting property of fluorinated compounds is the formation of ordered molecular aggregations to enhance the emission of certain types of compounds that have a twisted resonance structure [5]. Heavily studied HFB (C6F6) was reported to have non-covalent bonding interaction with an oxygen atom in water molecule with bonding energy of about −2 kcal/mol. Various binary complexations between HFB molecules show the interaction energy from −1.74 to −5.38 kcal/mol, depending on their interaction modes [6].

Meanwhile, over the past decades, attention was brought to phenol, indole, diphenylacetylene, aminobenzonitriles, and halogenated aromatics due to their unusually weak absorption and fluorescence without the 0–0 band, which is attributed to the low-lying πσ*, noted by research using diverse aromatic systems by authors [7]. Computational calculations with the CASSCF method for phenol reported by Sobolewski also support the increased photo-acidity of phenol is due to the low-lying πσ* state of O—H interacting with the S1(ππ*) state and the S0 state due to the proton transfer to water clusters in the solvent [8]. Interestingly, the repulsive πσ* with chlorine atom undergoes fast intersystem crossing to triplet states and would photochemically break a looser C-Cl bond [9].

In the gas phase 10,11, the decreased absorption and fluorescence were reported to be dependent on the number of fluorinated atoms on the aromatic ring. The phenomena are attributed to the energy level of πσ* states. For the aromatic rings in the vapor phase with up to 4 fluorine atoms, the resulting aromatic molecules exhibit structured absorption and fluorescence spectra, high fluorescence efficiency, and nanosecond fluorescence lifetimes. Therefore, it was suggested that ππ* is the first excited state, S1 [12–14]. However, the gaseous aromatic rings with 5 and 6 fluorine atoms display structureless absorption and excitation spectra, very weak fluorescence with the very low quantum efficiency and biexponential fluorescence decays with picosecond and nanosecond lifetimes. Thus, the observation concluded the transition is forbidden from and to low-lying πσ* states and computational results confirm this observation [15].

In our previous study in solution [16], it was reported that pentafluorophenylalanine (F5Phe) exhibited photophysical features similar to fluorinated benzenes of vapor phase that contained a low-lying πσ* state. However, although the photo-physics of the fluorinated benzenes are well reported both experimentally and theoretically in the gas phase, the effect of πσ* of fluorinated aromatics in solution hasn’t been fully studied especially with fluorinated benzenes. The previous researchers intentionally limited their study to the gas phase to avoid the influence of their surroundings in the condensed phase. The purpose of this study is to investigate the solvent effect on the transition involved in the πσ* state and the ππ* state for benzenes with various fluorine numbers in solution. To achieve this objective, UV–visible and fluorescence spectroscopy were used to measure the absorption and emission spectra of different fluorinated benzenes and their results were compared to that of F5Phe in various solvents. Additionally, for better understanding of the observed data, computational modeling was also performed to examine the nature of the π-σ* state.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials and methods

Chemicals

The following standards/reagents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich at 99 % purity: Anisole and the fluorinated benzenes fluorobenzene (FB), 1,2-difluorobenzene (12DFB), 1,3-difluorobenzene (13DFB), 1,4-difluorobenzene (14DFB), 1,2,3-trifluorobenzene (123TFB), 1,2,4-trifluorobenzene (124TFB), 1,3,5-trifluorobenzene (135TFB), 1,2,3,4-tetrafluoro-benzene (1234TFB), 1,2,3,5-tetrafluoro-benzene (1235TFB), 1,2,4,5-tetrafluorobenzene (1245TFB), pentafluorobenzene (PFB) and hexafluorobenzene (HFB). Also, the solvents hexane, acetonitrile and isopropyl alcohol and the proteins l-tyrosine (l-Tyr), phenylalanine (Phe) and pentafluorophenylalanine (F5Phe) are purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Deionized water was obtained from a Millipore Q-POD water deionizer and purifier.

Instrumentation

A JASCO V-570 UV/VIS/NIR spectrophotometer was used to obtain the absorbance of the different samples utilizing a 2.0 nm detection bandwidth and 2 transients at a scan rate of 400 nm/min with a 1.0 nm data pitch. All emission spectra were obtained using a PERKIN ELMER Luminescence Spectrometer LS 50B with an excitation slit of 2.5 nm and detection slit of 5.0 nm carried out at 400 nm/min over 2 transients.

Sample preparation and analysis

The molar extinction coefficients (ε) of the fluorinated benzenes were obtained by preparing three solutions of each fluorinated benzene in acetonitrile with absorbance ranging from 0.5 to 1.0. Each of these solutions was further diluted three times and the ε value was then found from Beer-Lambert’s Law.

In the determination of fluorescence quantum yields, samples producing absorptions of 0.1–0.2 were used, exciting at their corresponding λmax for absorption. l-Tyr was used as the fluorescence quantum yield standard with a quantum yield of 0.14 [17]. The effect of different solvents (acetonitrile, isopropanol and deionized water) was determined by obtaining the emission spectra of compounds that exhibited unusual emission spectrum. These compounds include 123TFB, 1234TFB, PFB and HFB with 13DFB used as control.

2.2. Molecular modeling

Theoretical calculations of the excited states of the molecules in question were carried out with the Gaussian 09 suite of programs [18] using a TD-SCF/DFT/BVP86/6-311G/++ basis set. This method was shown to provide an accurate prediction of jet-cooled fluorescence of fluorobenzenes [10]. Additional data was fed through the default solvation method to consider the possible effects of solvents.

3. Results and discussions

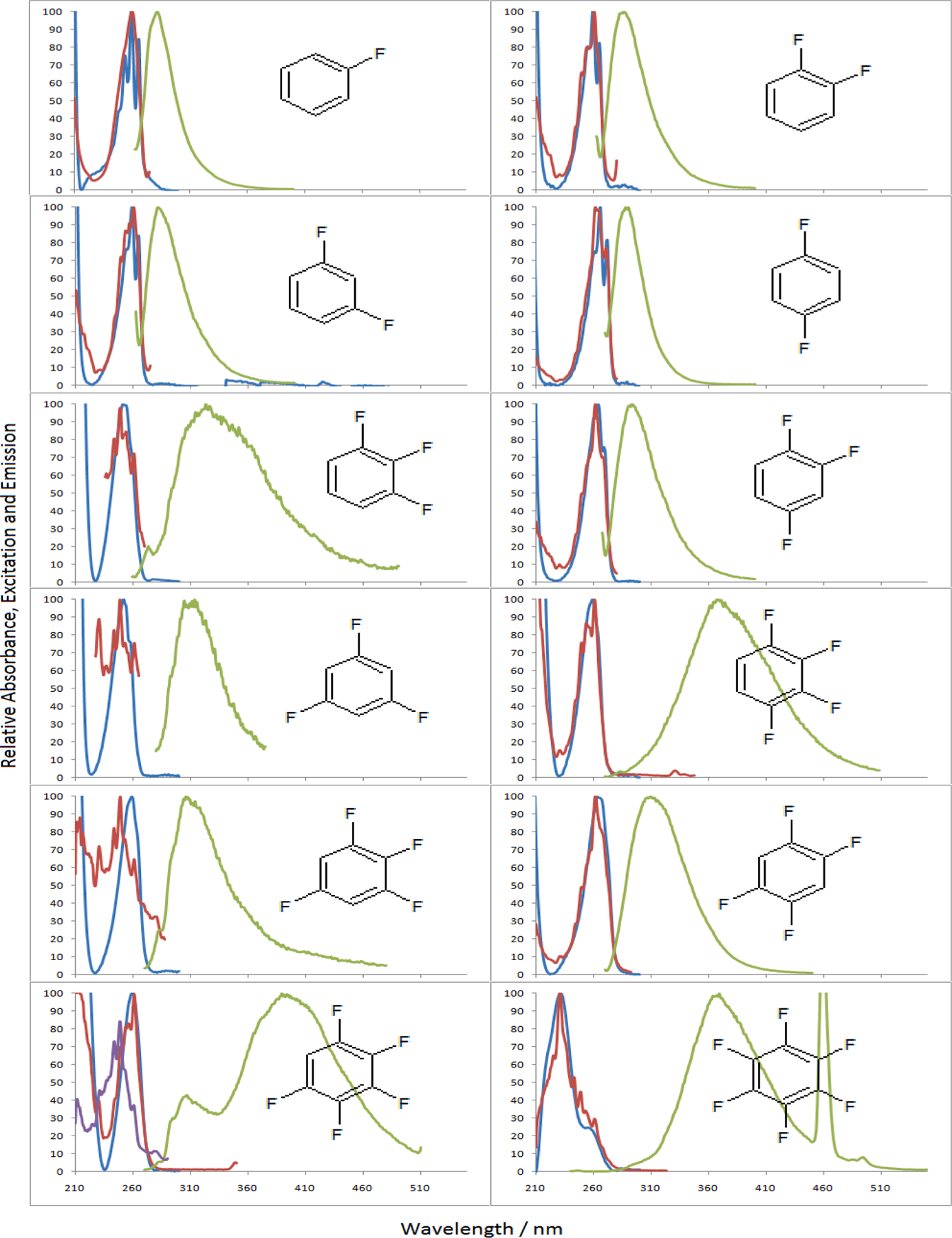

The absorbance, excitation and emission spectra of fluorinated benzenes were obtained using the following solvents: water, acetonitrile and isopropanol. The results in acetonitrile are shown in Fig. 1. Generally, in acetonitrile solution, the absorption for all samples except HFB occurs at around 260 nm (also shown in Fig. 2). Although the effect is not significant, more fluorine substitution on the ring follows the previously observed trend of narrowing energy gap between HOMO and LUMO in the gas phase. Fluorescence show the decrease in transition energy (reflecting energy gap decrease between S0 and S1) in a more dramatic manner by having more fluorines on the ring. Also, in general, the excitation spectra confirm the standard photophysical behavior of excited states with closely lying S1 and S2. It should be noted that the Gaussian modeling shows that the energy of HOMO and LUMO decreases with more fluorine atoms. 123TFB, 1234TFB, PFB and HFB have −0.27202, −0.27207, −0.27671, and −0.28675 Hartree, respectively for HOMO, while −0.03258, −0.04392, −0.04893, and −0.06078 Hartree for LUMO, in the order.

Fig. 1.

Normalized absorbance (blue) and emission (green) of the 12 fluorinated benzenes in acetonitrile with the corresponding excitation spectrum (red) for their λem max. The excitation spectrum of the 305 nm emission peak of PFB is also shown (purple). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

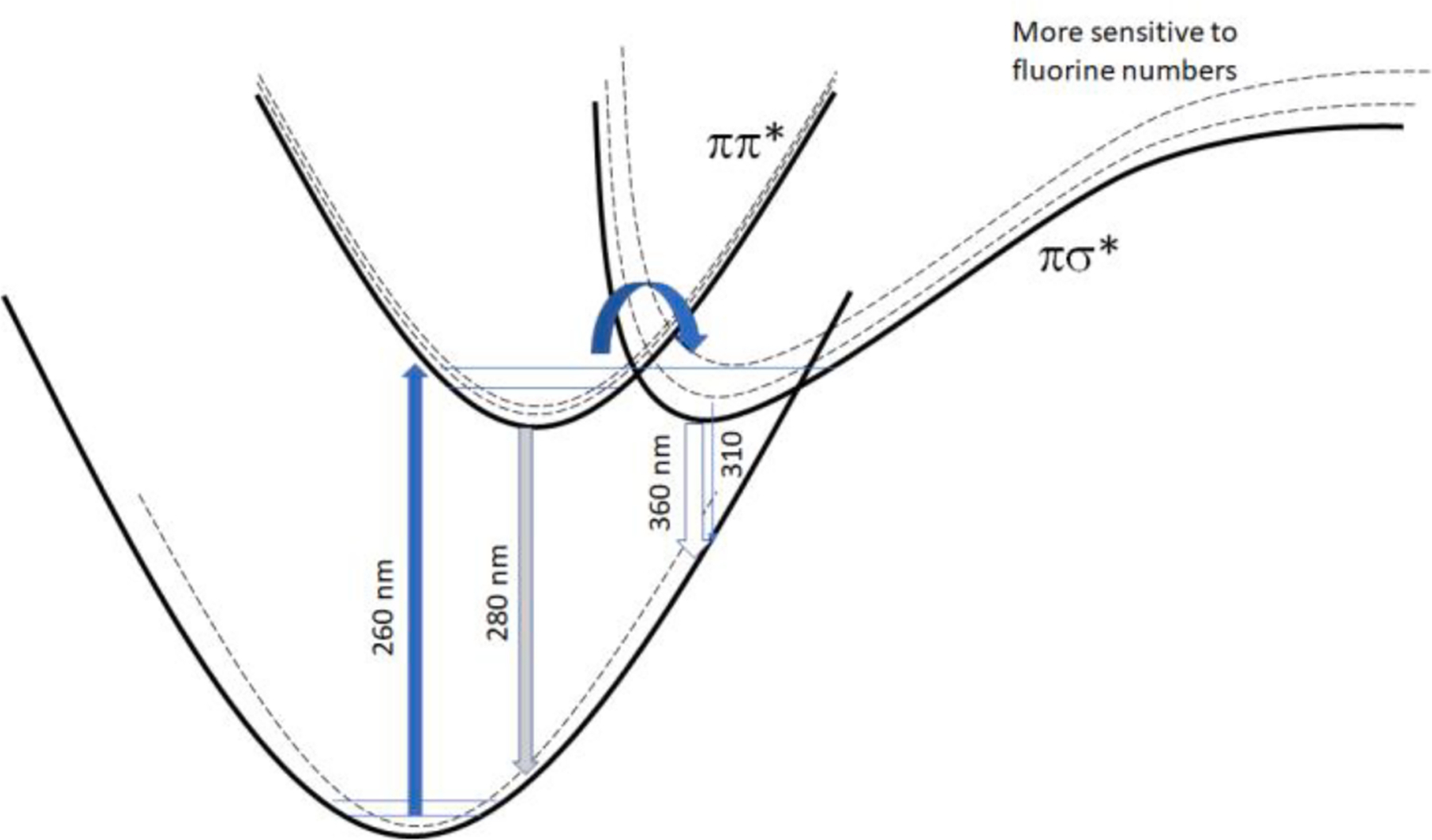

Fig. 2.

Absorption and emission between ground and excited state surfaces. The dotted curves are assumed curves with a different number of fluorine atoms for the ground state, ππ * and πσ * states. Shown on the graph is the typical S0 → S1(ππ *) transition at 260 nm and S1(ππ *) → S0 transition at 280 nm. The arrow indicates the possible crossing of a conical intersection.

3.1. Emission spectra

The emission maxima (λem max) of FB (C6H5F) and the DFBs (C6H4F2: 1,2-, 1,3- and 1,4-difluorobenzes are abbreviated as 12DFB, 13DFB, and 14DFB respectively) are at 283, 286, 282, and 288 nm respectively. Upon addition of another fluorine to give the trifluorinated benzenes (C6H3F3:1,2,3-, 1,3,5- and 1,2,4-trifluorobenzenes are abbreviated as 123TFB, 135TFB, and 124TFB respectively), the λem max was red shifted to 345, 309, and 293 nm, respectively. It should be noted that consecutive fluorination on 123TFB gives the most red-shift among the isomers. The tetrafluorinated benzenes (C6H2F4: 1,2,3,4-, 1,2,4,5-, 1,2,3,5-tetrafluorobenzenes are abbreviated as 1234TFB, 1245TFB, and 1235TFB respectively) exhibited λem max at 367, 309, and 306 nm; again, it should be noted that consecutive fluorination on 1234TFB shows the most effect in red-shift. Lastly, For the naturally consecutive fluorine substituted benzenes (PFB and HFB), PFB (C6HF5: 1,2,3,4,5-pentafluorobenzene) showed λem max at a much longer wavelength: 389 and 305, while HFB (C6F6: 1,2,3,4,5,6-hexafluorobenzene) at 365 nm.

Fig. 2 sketches absorption and emission between ground and excited state surfaces of samples. The dotted curves are assumed curves with different numbers of fluorine atoms for the ground state, ππ *, and πσ* states. Compounds like 124TFB, 135TFB, and tetrafluorobenzene isomers have emissions around 310 nm, while compounds with consecutive fluorines like 123TFB and 1234TFB show fluorescence intensity around 360 nm. Further stabilized πσ* state of PFB even shows at 390 nm in Fig. 1.

Meanwhile, HFB was found to be the only compound with nearly no absorption around 260 nm; instead, it shows at 231 nm. This strongly suggests that the absorption transition to S1 state is symmetrically forbidden. Therefore, it is reasonable to say that the energy of πσ * for HFB became lower than ππ * to cause a weak forbidden absoption to S1, πσ * state. Thus, the observed peak at 231 nm is the transition to upper level ππ * state like S3.

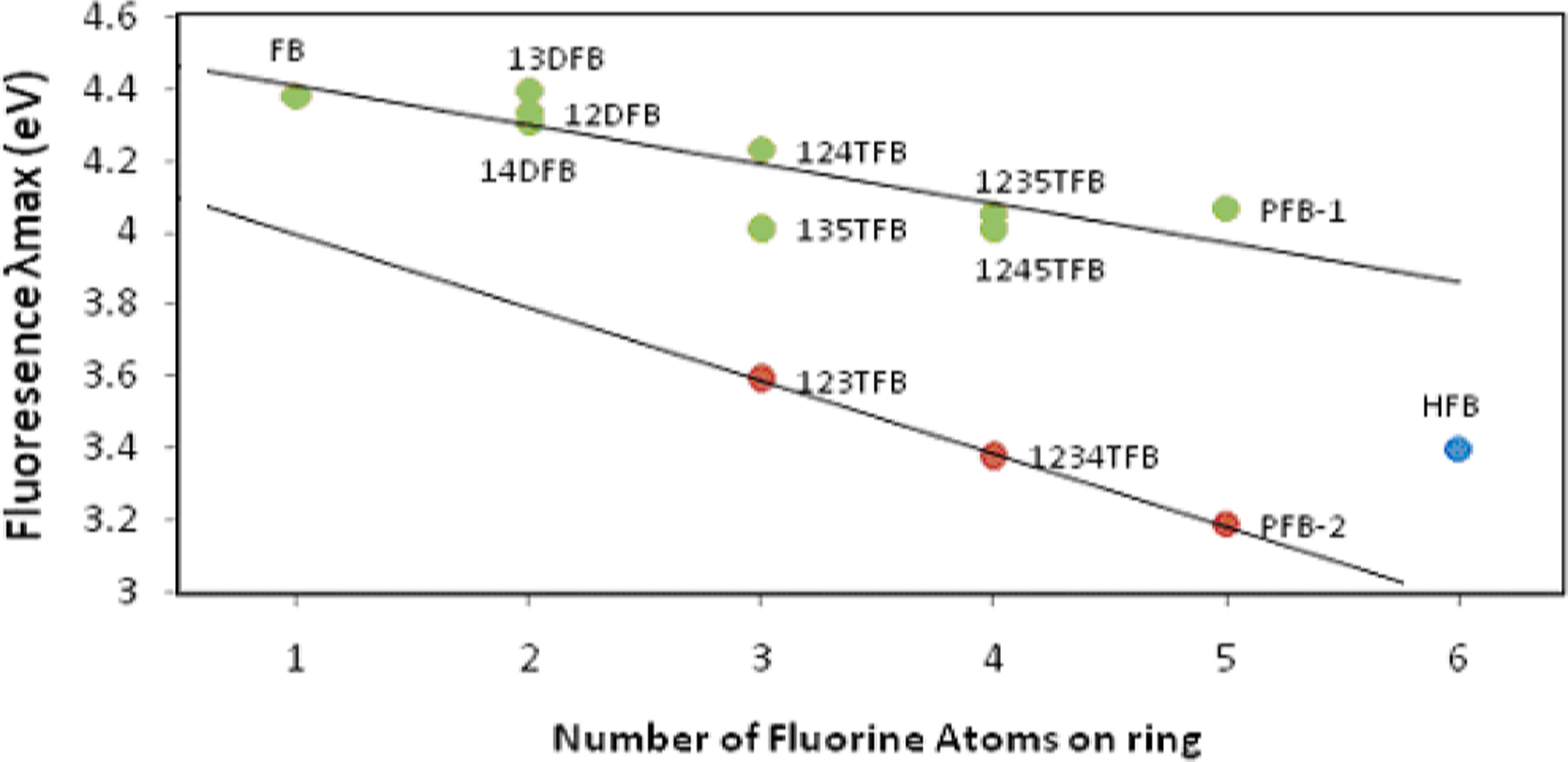

These energy gaps of observed emission are plotted in eV vs the number of fluorine atoms in Fig. 3. Two discrete linear trendlines were found. Interestingly, different from the results of gas phase, the rings with fluorine atoms consecutively showed a greater slope and have the emission peaks shift further compared to other isomers: 123TFB at 345 nm, 1234TFB at 367 nm, and PFB (C6HF5) at 389 nm. Based on the reported studies and calculations from the gas, ππ * does not greatly change the energy by fluorine numbers on the ring. It supports the observed spectra with the nearly constant transition of gaseous samples around 260 nm for absorption and around 280 for emission. Thus, it appears that both trendlines in Fig. 3, apart from the behavior of ππ * in gas phase, demonstrate sensitivity to the total number of fluorine atoms on the ring, and this outcome assimilates the πσ * in the reported results of the gas phase and the theoretical study [10]. The sensitivity (Figs. 2 and 3) of πσ * for fluorine numbers was attributed to the fact that πσ * is a more polar state with high contribution of σ* (C-F bond). Through various researches, it was concluded that the σ frame gets destabilized by the contribution of more fluorine atoms (i) through-space non-bonding interaction (ii) πelectron back-binding, and (iii) σ induction 19,20. Through-space interaction is the greatest cause for the destabilization of fluorinated benzenes, and the repulsion can act as the driving force for rings with adjacent fluorines towards out-of-plane geometry at an excited state as reported for PFB and HFB in the gaseous state [11].

Fig. 3.

The energies of the λem max of fluorinated benzenes. The energy of all emissions, with the exception of 123-TFB, 1234-TFB and the 305 nm peak of PFB, closely resemble the theoretical values.

The driving forece from the through-space interaction is believed to facilitate the vibronic mixing with a certain type of vibronic mode. Moreover, the the energy of the σ*orbital with a flat geometry stabilizes along with more fluorination according to our modeling result; especially, the consecutive fluorine substitution compared to other isomers shows a greater decrease in πσ * energy level as observed in Fig. 3.

The width of the peaks in Fig. 1 for 123TFB (C6H3F3) and 1234TFB (C6H2F4) are wider than those of ππ * for other corresponding isomers. In fact, although the peak-broadening effect by πσ * is less pronounced, even for compounds with some partially adjacent fluorine atoms like 124TFB and 1235TFB, the peak-broadening on the tail area of the peak is shown when compared to those without any adjacent ones. In contrast, this was only observed for PFB (C6HF5) and HFB (C6F6) in gas phase. Therefore it can be concluded that solution state influences the energy level of the polar πσ *, especially for the consecutively substituted rings. This behavior is different from gas-phase results.

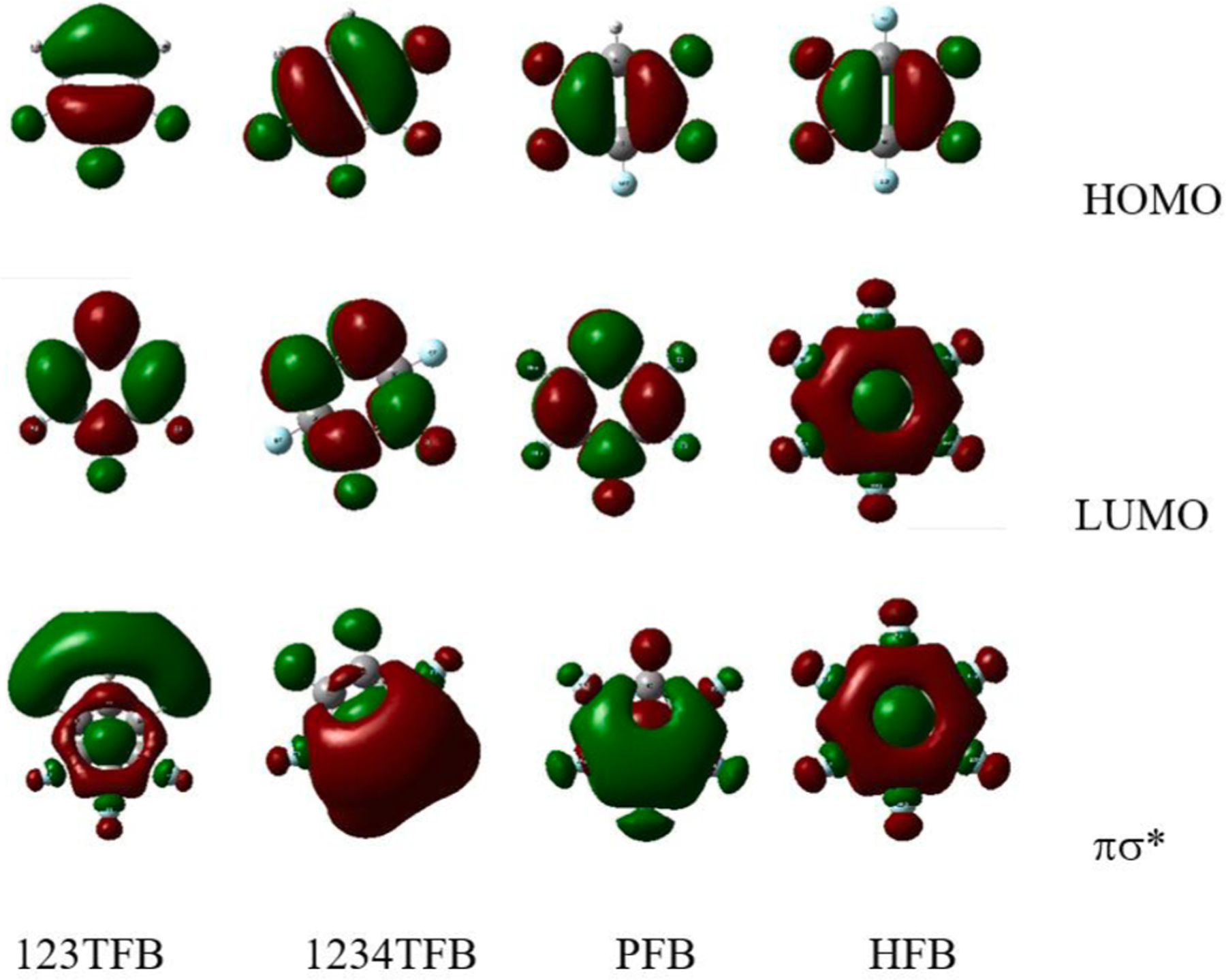

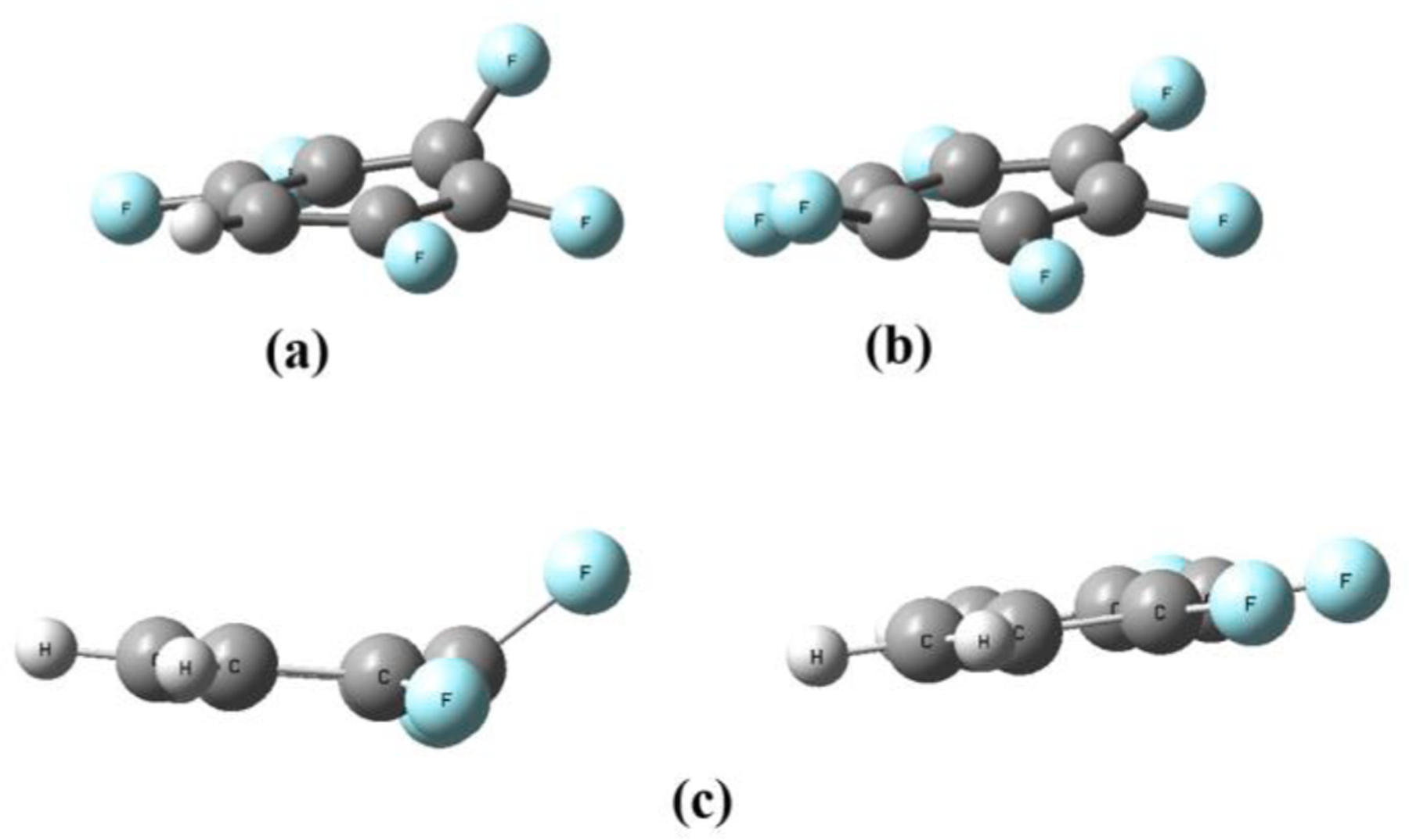

When MOs are compared in Fig. 4, the rings with consecutive substitution have σ * orbitals of carbons in C-F to overlap through the carbon backbone of the ring and, especially, inside of the ring. This is believed to provide extra stability for πσ * state of these compounds. Additional insight comes from TDDFT calculation (Fig. 5) after virtical excitation at the flat geometry, when the geometry of the excited states for compounds with five or six fluorines was examined. The calculation shows that change to the boat-shaped structure at the energy minima of the excited state further lowers the energy for highly repulsive rings like PFB and HFB. It is considered that, even with greater repulsion between six fluorine atoms on HFB, the strong overlap of carbon p-orbitals in σ * of C-F bonds (in Fig. 4) resists the bending. The calculation results for the excited state show that the out-of-plane fluorine is twisted by 55 degrees for PFB (Fig. 5-(a)) while it was 45 degrees for HFB (Fig. 5-(b)). This could be the reason why HFB shows an emission not following the trendline in Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

HOMO, LUMO, and πσ * orbitals of 123TFB, 1234TFB, PFB and HFB. p-orbitals in σ * of fluorine (C-F) have same phase; p-orbitals of carbons also aligned with the same phase.

Fig. 5.

Out-of-plane (e2u symmetry) of (a) PFB, (b) HFB and (c) dimer of 123TFB by TDDFT modeling for S1 state.

Furthermore, using the same TDDFT calculation, authors attempted to examine the effect of stacking between fluorinated rings, hinting at a mode only possible in solution, not in gas phase. As expected, 123TFB did not show the out-of-plane conformation when a single molecule was used, but the dimer of 123TFB unexpectedly showed that one of the molecules with the out-of-plane conformation as shown in Fig. 5-(c). The σ * character shown at the tail of the emission spectrum for solution samples (even for 123TFB) was observed from the MO graph of LUMO from TDDFT modeling. LUMO had electron density on the deformed molecule among the dimer molecules, while the HOMO had electron density on the flat molecule of the dimer. This implies charge transfer (CT) to form exciplex in the solution state.

3.2. Emission intensity

As shown in Table 1, the quantum efficiency of emission decreased dramatically with fluorine atoms present on the ring; especially those with three or more fluorine atoms gave ϕ (quantum efficiency) of fluorescence in numbers with three decimal places. Since substitution of more than three fluorines lowers energy of the πσ * surface, it is reasonable to believe that the crossing from ππ * to πσ * surface became less endothermic with lowered πσ * energy level. Additionally, as stated above, more fluorine substitution will facilitate the out-of-plane vibration to increase the conical crossing. Then, more crossing decreases the relaxation from ππ * (Fig. 2 and Table 1) and, the increased relaxation from πσ * will have a bad emission efficiency due to the forbidden symmetry. Thus, it is speculated that the conical crossing efficiency is responsible for and will explain the emission efficiency, since the vibronic mixing with e2u vibrational mode (boat and chair symmetry) could facilitate the formation of the most stable excited state conformation in boat or chair form [19–21]. 1234TFB with greater through-space interaction among fluorine atoms and lower πσ * energy level has 10-fold greater efficiency than 123TFB. With an assumption that 1234TFB undergoes more crossing, the 10-fold greater efficiency would only make sense if the πσ * →S0 transition became more efficient with 1234TFB.

Table 1.

The calculated molar extinction coefficients and fluorescence quantum yields of the fluorinated benzenes in acetonitrile.

| Compound | Ground State Symmetry | ε (M−1cm−1) | ΦF | Excitation wavelength (nm ± 2.5 nm) | Emission λmax (nm ± 2.5 nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FB | C2v | 254 nm – 571 ± 41 260 nm – 757 ± 51 266 nm – 600 ± 38 |

0.043 ± 0.002 | 260 | 283 |

| 12DFB | C2v | 255 nm – 736 ± 9 260 nm – 871 ± 13 265 nm – 676 ± 10 |

0.038 ± 0.002 | 260 | 286 |

| 13DFB | C2v | 259 nm – 780 ± 14 265 nm – 632 ± 14 |

0.025 ± 0.001 | 259 | 282 |

| 14DFB | D2h | 266 nm – 2149 ± 71 272 nm – 1742 ± 66 |

0.102 ± 0.006 | 266 | 288 |

| 123TFB | C2v | 251 nm – 160 ± 15 |

0.0042 ± 0.0003 | 251 | 345 |

| 124TFB | Cs | 264 nm – 1442 ± 90 269 nm – 1106 ± 69 |

0.135 ± 0.008 | 264 | 293 |

| 135TFB | D3h | 252 nm – 137 ± 9 |

0.0033 ± 0.0005 | 252 | 309 |

| 1234TFB | C2v | 260 nm – 1338 ± 51 |

0.050 ± 0.003 | 259 | 367 |

| 1235TFB | C2v | 259 nm – 642 ± 26 |

0.0058 ± 0.0004 | 259 | 306 |

| 1245TFB | D2h | 263 nm – 1724 ± 98 |

0.080 ± 0.005 | 263 | 309 |

| PFB | C2v | 260 nm – 651 ± 5 |

0.041 ± 0.002 | 259 | 305 389 |

| FB | D6h | 231 nm – 663 ± 2 |

0.078 ± 0.005 | 231 | 365 |

Meanwhile, when fluorine atoms are present on 1 and 4 positions with or without additional fluorine atoms on other carbons, the ring increases the quantum efficiency for emission by 10 – 25 times. For example, the quantum efficiency for 14DFB and 124TFB is over 0.1 while 123TFB has a quantum efficiency of 0.0042. Also, isomers with substitutions on 1 and 3 positions show much weaker intensity. Although the polarity of rings with sustitution on 1 and 4 increases as they fold to out-of-plane conformation in the excited state. Thus, it appears that the quantum efficiency is not just the result of energetics for energy levels, through-space interaction, and vibronic mixing mentioned above. Comapred to gas phase, the stabilization of these folded polar structure can be greater. Most importantly, the authors also observed that the fluorescence intensity is sensitive to the type of solvent and concentration. This suggests self-quenching by self-assembly interactions in a solvent cage. 123TFB revealed self-quenching of fluorescence at a concentration higher than 10−5 mol/L and 1234TFB showed similar behavior at 7 × 10−6 mol/L and above.

3.3. Solvent effect

In order to examine the nature of the solvent-mediated stabilization, emissions of the compounds exhibiting πσ*→S0 transition have been carried out in water, acetonitrile, and isopropanol. As shown in Fig. 6, unlike 13DFB (the control), other samples with consecutive fluorines show multiple emission peaks with generally lower quantum efficiency compared to that of benzene. As mentioned above, it can be attributed to self-quenching in solvent cage, since highly fluorinated compounds show excellent self-association ability. In general, the relative emission efficiency increases around 325 nm in water compared to the other two solvents. Also, more πσ * feature is shown over 350 nm. Meanwhile, as shown in Table 2, the vertical excitation energy does not change dramatically, therefore these emissions are from minima of πσ * with out-of-plane structure.

Fig. 6.

The normalized emission of 13DFB, 123TFB, 1234TFB, PFB and HFB in water (blue), acetonitrile (red) and isopropanol (green). The Raman scattering of water was observed in the emission spectra of 1234TFB and PFB. The narrow peaks observed in the emission spectra of HFB at 262 nm are attributed to the second-order detection of the excitation wavelength. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 2.

The vertical excitation energies of fluorinated benzenes using the default solvation method in the TD-SCF/DFT/BPV86/6-311G++ basis set (with the nature of the excited states in parenthesis).

| Compound | Calculated vertical excitation energy (eV) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no solvent |

acetonitrile |

water |

|||||||

| s0 → s1 | s0 → s2 | s0 → s3 | s0 → s1 | s0 → s2 | s0 → s3 | s0 → s1 | s0 → s2 | s0→s3 | |

| FB | 5.2176 (π*) | 6.0165 (σ*) | 6.0912 (π*) | 5.2393 (π*) | 6.1058 (σ*) | 6.2397 (π*) | – | – | – |

| 12-DFB | 5.1474 (π*) | 6.0313 (π*) | 6.0588 (σ*) | 5.1803 (π*) | 6.0594 (π*) | 6.2069 (σ*) | – | – | – |

| 13-DFB | 5.1601 (π*) | 6.0420 (π*) | 6.2153 (σ*) | 5.1876 (π*) | 6.0471 (π*) | 6.3938 (σ*) | 5.1885 (π*) | 6.0481 (π*) | 6.3940 (σ*) |

| 14-DFB | 5.0241 (π*) | 6.0338 (π*) | 6.0910 (σ*) | 5.0614 (π*) | 6.0378 (π*) | 6.2663 (σ*) | – | – | – |

| 123-TFB | 5.1227 (π*) | 5.8740 (σ*) | 5.9112 (σ*) | 5.1561 (π*) | 5.7560 (σ*) | 5.8185 (σ*) | 5.1645 (π*) | 5.7283 (σ*) | 5.7916 (σ*) |

| 124-TFB | 5.0099 (π*) | 5.9954 (π*) | 6.1112 (σ*) | 5.0487 (π*) | 6.0109 (π*) | 6.0627 (σ*) | – | – | – |

| 135-TFB | 5.1326 (π*) | 6.0101 (π*) | 6.6137 (σ*) | 5.1464 (π*) | 6.0102 (π*) | 6.5257 (σ*) | – | – | – |

| 1234-TFB | 5.0221 (π*) | 5.3913 (σ*) | 5.7356 (σ*) | 5.0706 (π*) | 5.2968 (σ*) | 5.6124 (σ*) | 5.072 (π*) | 5.2932 (σ*) | 5.6082 (σ*) |

| 1235-TFB | 5.0210 (π*) | 5.6705 (σ*) | 5.9618 (σ*) | 5.0517 (π*) | 5.5935 (σ*) | 5.8425 (σ*) | – | – | – |

| 1245-TFB | 4.8990 (π*) | 5.8411 (σ*) | 5.9712 (π*) | 4.9481 (π*) | 5.8242 (σ*) | 5.9829 (π*) | – | – | – |

| PFB | 4.9615 (π*) | 5.1014 (σ*) | 5.3952 (σ*) | 5.0072 (π*) | 5.0383 (σ*) | 5.2918 (σ*) | 5.0088 (π*) | 5.0348 (σ*) | 5.2857 (σ*) |

| HFB | 4.7117 (σ*) | 4.7124 (σ*) | 4.9439 (π*) | 4.6443 (σ*) | 4.6452 (σ*) | 4.9817 (π*) | 4.6409 (σ*) | 4.6416 (σ*) | (σ*) |

It was first attributed to solvation according to polarity; thus the dipole moments of each compound were compared using Gaussian calculation (Fig. 7). It turned out that more fluorinated rings are generally less polar: 3.01, 2.54, 1.42, and 0.0003 Debye for 123TFB, 1234TFB, PFB, and HFB respectively. Interestingly, fluorine atoms for all samples (123TFB, 1234TFB, PFB, HFB) have relatively similar amounts of negative charge, around −0.35. However, carbon-bearing fluorine atoms have a significantly different positive charge from 0.1 to 0.489: in general, the carbon of C-F next to methine has the least amount of positive charge.

Fig. 7.

Charge distribution of 123TFB, 1234TFB, PFB, and HFB calculated by DFT.

The calculations shown in Table 2 predict that the s0 → ππ* energy is increased in solvents (in the S3 state for HFB and S1 state for all other compounds). In contrast, the energy gap between S0 and πσ* decreases for those compounds with a consecutive substitution that exhibited red-shifted emission spectra (the S2 and S3 states in 123-TFB, 1234-TFB and PFB and the S1 and S2 states in HFB) due to more polar nature of σ*. Due to the forementioned low polarity of overall dipole moment at the ground state, the different polarity solvent does not seem to affect these vertical transitions significantly. However, it provides evidence that these πσ*→S0 transitions from the mina of the energy surface (Fig. 2) are red-shifted by solvation. A similar dependence of the πσ*→S0 transition on solvent has been observed in 4-(Dimethylamino)benzonitrile (DMABN) [11] and attributed to a charge-separation-like nature of the πσ* state. In addition, these compounds appear to form self-assemblies (Fig. 5-c) particularly in water, as stated above, causing the character of CT state. Thus the peak at 325 nm is attributed to the relaxation from the CT state to S0.

Meanwhile, as shown in Fig. 8, the fluorescence of the benzenes with consecutive fluorines in hexane was measured in comparison to results from the polar solvents mentioned above. Since hexane cannot stabilize the polar πσ * state greatly, the fluorescence peaks (dotted lines in Fig. 8) are blue-shifted from the peaks obtained in the polar acetonitrile solution (Table 1): from 345 to 322.5 nm for 123TFB, from 367 nm to 346 nm for 1234TFB, from 389 to 376.5 nm for PFB, and from 365 to 362 nm for HFB. When tri-substituted 123TFB exhibits a 22.5 nm shift, hexa-substituted HFB shows a 3 nm shift. This trend appears to agree with the calculation data above that the more highly substituted fluorobenzene is less polar. Thus, less polarity of HFB seems to cause a much weaker solvation effect.

Fig. 8.

The relative emission of 123TFB (red dotted line), 1234TFB (orange dotted line), PFB (green dotted line), and HFB (blue dotted line) in hexane. The quenched emission of the same benzenes with anisole (1:1 ratio): 123TFB (solid red line), 1234TFB (solid orange line), PFB (solid green line), and HFB (solid blue line). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Moreover, adding electron-rich anisole (1 equivalent) to the fluorinated benzenes in hexane completely quenched the fluorescence over 330 nm for 123TFB, 1234TFB, PFB, and HFB; this results in a weak emission around 300 nm, as shown in Fig. 8. It is reasonable to believe that the peak at 300 nm is from ππ *, which is relatively insensitive to the number of fluorinations. This observation is attributed to the quenching of the polar πσ * state. Thus, it suggests a possible assembly between an electron-poor fluorinated ring and an electron-rich anisole ring in non-polar hexane. This intriguing behavior in solution is additional evidence for the increased emission process from πσ * followed by ISC from ππ *, as shown in Fig. 2.

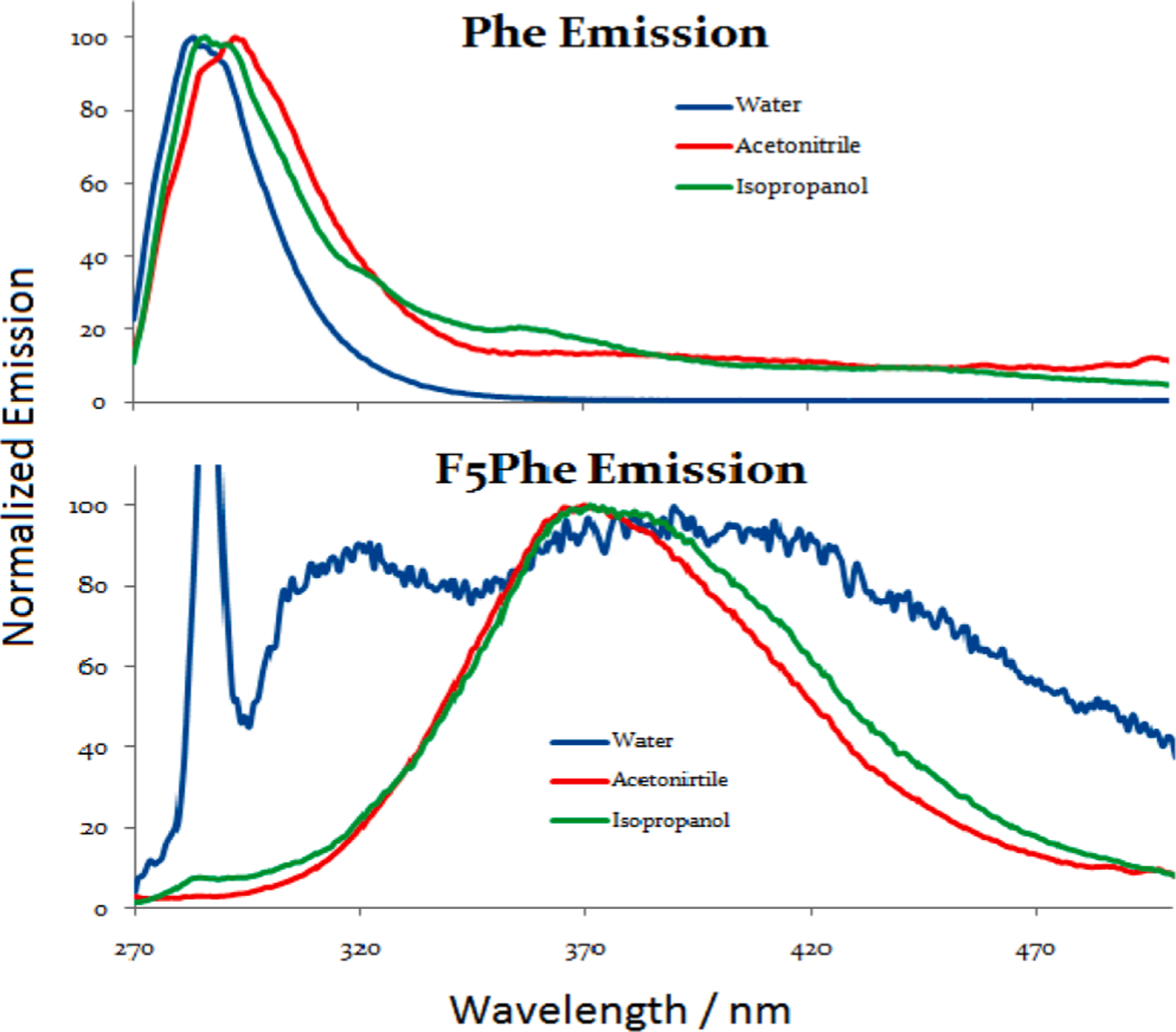

3.4. Pentafluorophenylalanine

Pentafluorophenylalanine (F5Phe) is similar in structure to PFB and therefore, is also expected to exhibit πσ*→S0 emission. In water, F5Phe is also expected to show the peak corresponding to the transition from CT state to ground state. Compared to PFB, it shows the same emission in acetonitrile and isopropanol. However, it shows stronger emission around 360–470 nm region while the same intense peak shows at 310 nm. The stronger peak over 360 nm can be attributed to extra-stabilization of the πσ * state by the intramolecular influence of polar functional groups, amino and carboxylic groups. In comparing the emission spectrum of F5Phe to phenylalanine (Phe) (Fig. 7), we observed that Phe displays the expected emission spectrum (an S1(ππ*) → S0 transition) with little to no solvent dependence of the λem max, whereas F5Phe shows the predicted widening with the two peaks attributed to ππ*→S0 and πσ*→S0 transitions clearly visible for the spectrum in water. These effects are also reflected in the theoretical calculations (Table 3).

Table 3.

The vertical excitation energies of Phe and F5Phe using the default solvation method and the TD-SCF/DFT/BPV86/6-311G++ basis set (the nature of the excited states are in parenthesis).

| Compound | Calculated vertical excitation energy (eV) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no solvent |

acetonitrile |

|||||

| s0→s1 | s0→s2 | s0→s3 | s0→s1 | s0→s2 | s0→s3 | |

| Phe | 3.0695 (π*) |

3.1703 (π*) |

3.5548 (σ*) |

3.0713 (π*) |

3.3078 (π*) |

3.7344 (σ*) |

| Phe | 1.3118 | 2.5018 | 2.8219 | 2.7802 | 3.3774 | 3.5137 |

| F5Phe | 2.4549 (π*) |

2.5856 (σ*) |

2.6484 (σ*) |

2.4350 (π*) |

2.5556 (σ*) |

2.5936 (σ*) |

| F5Phe† | 0.5767 | 0.8452 | 1.0802 | 0.8981 | 1.0078 | 1.3025 |

- these calculations were done using the zwitterion structure of the amino acids.

The zwitterion structures were included because the emission spectra (Fig. 9) were all taken at a neutral pH (no pH adjustments were made). However, these values predicted vertical excitation energies that are much lower than those observed. The non-zwitterion structures predicted vertical excitation energies closer to those observed and a red-shift for the S0 → πσ* transition of F5Phe; however, the opposite is observed for Phe when in solution. As mentioned above, this is an additional indication of the stabilizing effect of solvents and intramolecular interaction on the πσ* state of F5Phe that causes the observed widening and red-shifted emission spectrum resulting from a πσ*→S0 transition.

Fig. 9.

The normalized emission spectra of Phe and F5Phe in water (blue), acetonitrile (red) and isopropanol (green). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Conclusion

Despite of the useful properties of fluorinated aromatic compounds in pharmaceutics and drug delivery, the ‘dark’ πσ * state deters their application in some field like bio-marker and sensor. However, we conclude that the fluorescence intensity over 300 nm improves in solution compared to in gas. Most notable finding is that the rings with more than three consecutive fluorines show significant πσ * feature including penta- and hexafluorobenzene. According to our modeling in solution, it turned out that PFB and HFB show the similar out-of-plain structure to those from gas phase study. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 5, 123 and 1234 dimer also show a similar structure that is known to facilitate conical crossing. According to computational results, more substituted compounds are less polar with the flat geometry compared to the out-of-plain conformation. Thus, we believe the solvation can stabilize and facilitate the folding to exhibit stronger fluorescent feature from πσ * state. Thus, 123- or 1234-TFB should be further studied to apply them in sensor and bio-marker research in solutions.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the IH AREA grant (1R15GM134491-01). The authors are thankful to Chemistry Department of York College for the support and facilities that made the research possible.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Poleto MD, Rusu VH, Grisci BI, Dorn M, Lins RD, Verli H, Aromatic rings Commonly used in medicinal chemistry: Force fields comparison and interactions with water toward the design of new chemical entities, Front. Pharmacol 9 (2018) 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dichiarante V, Milani R, Metrangolo P, Natural surfactants towards a more sustainable fluorine chemistry, Green Chem 20 (2018) 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gillis E. p.; Eastman KJ; Hill MD; Donnelly DJ; Meanwell NA Application of fluorine in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem 2015, 58, 8315–8359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wang BC, Wang LJ, Jiang B, Wang SY, Wu N, Li XQ, Shi DY, Application of fluorine in drug design during 2010–2015 years: A mini-review, Mini Rev. Med. Chem 17 (2017) 683–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Suzuki S, Sasaki S, Sairi AS, Iwai R, Tang BZ, Konishi G, Principles of aggregation-induced emission: design of deactivation pathways for advanced AIEgens and applications, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 59 (2020) 9856–9867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Varadwaj P, Varadwaj A, Marques H, Yamashita K, Can combined electrostatic and polarization effects alone explain the F F Negative bonding in simple fluoro-substituted benzene derivatives? A first-principles perspective, Computation 6 (2018) 51–85. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Morita M, Yamada S, Konno T, Systematic studies on the effects of fluorine atoms in fluorinated Tolanes on their photophysical properties, Molecules 26 (2021) 2274–2286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sobolewski AL, Domke WJ, Photoinduced electron and proton transfer in phenol and its clusters with water and ammonia, Phys. Chem. A 105 (40) (2001) 9275–9283. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Terlizzi LD; Roncari F; Crespi S; Protti S; Fagnoni M Aryl-Cl vs heteroatom-Si bond cleavage on the route to the photochemical generation of σπ-heterodiradicals. Photochem. Photobio. Sci 2022, 21, 667–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zgierksi MZ; Fujiwara T; Lim EC Photophysics of aromatic molecules with low-lying πσ * states: fluorinated benzenes. J. Chem. Phys 2005, 122. 144312, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zgierski MZ, Fujiwara T, Lim EC, Role of the ps* state in molecular photophysics, Acc. of Chem. Res 43 (2010) 506–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Frueholz RPF, Mosher OA, Kuppermann A, Electronic spectroscopy of benzene and the fluorobenzenes by variable angle electron impact, J. Chem. Phys 70 (1979) 3057–3070. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Philis J, Bolovinos A, Andritsopoulos G, Pantos E, Tsekeris P, A comparison of the absorption spectra of the fluorobenzenes and benzene in the region 4.5–9.5 eV, J. Phys. Chem B 14 (1981) 3621–3635. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Robin MB, Higher Excited States of Polyatomic Molecules, Academic Press, New York, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- [15].O’Connor DVS, Morris JM, Yoshihara K, Non-exponential picosecond fluorescence decay in isolated pentafluorobenzene and hexafluorobenzene, Chem. Phys. Lett 93 (1982) 350–354. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Desamero RZB, Kang J, Dol C, Chingwong J, Walters K, Sivarajah T, Profit A, Spectroscopic characterization of the SH2- and active site-directed peptide sequences of a bivalent Src kinase inhibitor, Appl. Spectrosc 63 (2009) 767–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lakowicz JR, Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 2nd., Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Frish MJ, et al. , Gaussian 09, Revision B.01, s.n, Wallingford, CT, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Monda T, Mahapatra S, Photophysics of fluorinated benzene. 1. Quantum chemistry, J. Chem. Phys 133 (0884304) (2010) 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bartic D, Kovacevic B, Maksic ZB, Muller T, A novel approach in analyzing aromaticity by Homo- and Isostructural reactions: ab initio study of fluorobenzenes, J. Phys. Chem. A 109 (2005) 10594–10606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Penfold TJ, Worth GA, A model Hamiltonian to simulate the complex photochemistry of benzene II, J. Chem. Phys 131 (064303) (2009) 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]