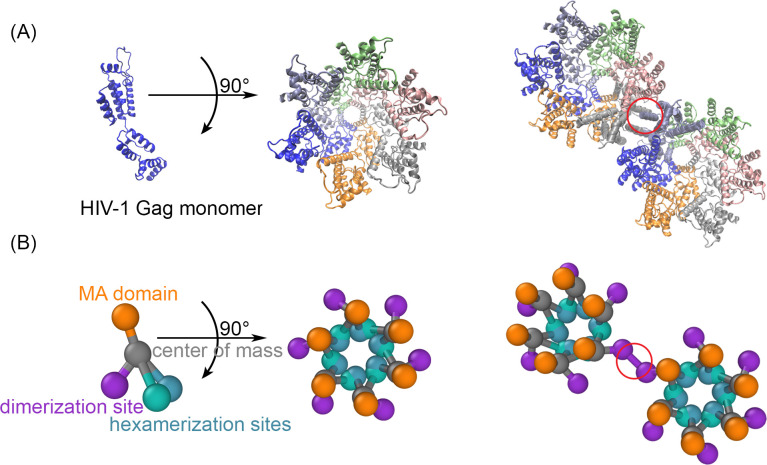

Figure 1. The structure-resolved reaction-diffusion model for Gag assembly on spherical membranes.

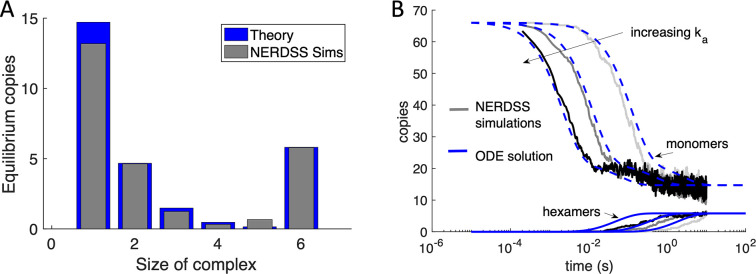

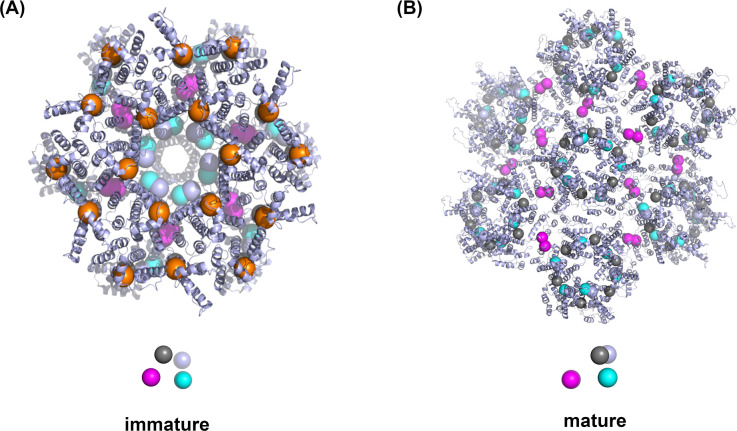

(A) The Gag monomers from the cryoET structure of the immature lattice (Schur et al., 2016) taken from 5L93.pdb is shown on its own, as part of a single hexamer (center), and with a dimerization interface in the red circle that brings together two hexamers (right). (B) Our coarse-grained model is derived from this structure to place interfaces on each monomer at the position where they bind. The reaction network contains three types of interactions. The MA domain (orange) binds to the membrane. The position of the MA site is not in the cryoET structure, and we position it to place each monomer normal to the surface. The distance of the MA site from the center of mass is set to 2 nm. The hexamerization sites (green and blue) mediate the front-to-back binding between monomers to form a cycle. The dimerization site (purple) forms a homo-dimer between two Gag monomers, as illustrated on the right. The reactive sites are point particles that exclude volume only with their reactive partners at the distances shown. Thus, the hexamer-hexamer binding radius is 0.42 nm, whereas the longer dimer-dimer binding radius is 2.21 nm. Positions and orientations are defined in Source Data. The experimental lattice has an intrinsic curvature, and our model recapitulates this to assemble a sphere. The binding kinetics between the interaction types for multiple rates was validated against theory (Figure 1—figure supplements 1 and 2), and we verified that the lipid binding site model did not significantly impact the dynamics of the lattice (Figure 1—figure supplement 3). The positioning of the Gag interfaces in this model of the immature lattice are distinct from a model that would assemble the mature lattice (Figure 1—figure supplement 4).