Abstract

There are no approved medicines for fragile X syndrome (FXS), a monogenic, neurodevelopmental disorder. Electroencephalogram (EEG) studies show alterations in resting-state cortical EEG spectra, such as increased gamma-band power, in patients with FXS that are also observed in Fmr1 knockout models of FXS, offering putative biomarkers for drug discovery. Genes encoding serotonin receptors (5-HTRs), including 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, and 5-HT1DRs, are differentially expressed in FXS, providing a rationale for investigating them as pharmacotherapeutic targets. Previously we reported pharmacological activity and preclinical neurotherapeutic effects in Fmr1 knockout mice of an orally active 2-aminotetralin, (S)-5-(2′-fluorophenyl)-N,N-dimethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-amine (FPT). FPT is a potent (low nM), high-efficacy partial agonist at 5-HT1ARs and a potent, low-efficacy partial agonist at 5-HT7Rs. Here we report new observations that FPT also has potent and efficacious agonist activity at human 5-HT1B and 5-HT1DRs. FPT’s Ki values at 5-HT1B and 5-HT1DRs were <5 nM, but it had nil activity (>10 μM Ki) at 5-HT1FRs. We tested the effects of FPT (5.6 mg/kg, subcutaneous) on EEG recorded above the somatosensory and auditory cortices in freely moving, adult Fmr1 knockout and control mice. Consistent with previous reports, we observed significantly increased relative gamma power in untreated or vehicle-treated male and female Fmr1 knockout mice from recordings above the left somatosensory cortex (LSSC). In addition, we observed sex effects on EEG power. FPT did not eliminate the genotype difference in relative gamma power from the LSSC. FPT, however, robustly decreased relative alpha power in the LSSC and auditory cortex, with more pronounced effects in Fmr1 KO mice. Similarly, FPT decreased relative alpha power in the right SSC but only in Fmr1 knockout mice. FPT also increased relative delta power, with more pronounced effects in Fmr1 KO mice and caused small but significant increases in relative beta power. Distinct impacts of FPT on cortical EEG were like effects caused by certain FDA-approved psychotropic medications (including baclofen, allopregnanolone, and clozapine). These results advance the understanding of FPT’s pharmacological and neurophysiological effects.

Keywords: Fmr1, serotonin, 5-HT1, EEG, alpha power, delta power, gamma power

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Fragile X syndrome (FXS), caused by epigenetic silencing of the FMR1 gene, is an X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder. It is the leading monogenic cause of intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In FXS, dysregulated expression and function of ion channels and ionotropic and metabotropic receptors1–3 can cause excessive pyramidal neuron firing and neural network activity,4–6 which likely contributes to neurological, psychiatric, and behavioral symptoms of FXS including seizures, cognitive rigidity, anxiety, sensory hypersensitivity, and social and communication deficits.7–9 Despite several breakthroughs in understanding its neuropathophysiology, there are currently no FDA-approved medicines for FXS.10

Recent studies of FXS aim to quantitatively assess cortical electroencephalogram (EEG) alterations as biomarkers to bridge the preclinical-to-clinical gap and provide more objective outcomes in clinical trials of pharmacotherapeutics for FXS. Clinical studies employing resting-state, non-task-related EEG—involving mostly male patients on psychotropic medications who were primed to relax and sit quietly during recordings—have revealed alterations in cortical EEG in FXS. The most consistent result across studies is an increase in gamma (30–80 Hz) power, and the next most consistent observation is a decrease in alpha (8–12 Hz) power;11–16 females with FXS present with different resting-state cortical EEG patterns.16 The increase in gamma power has also been observed in Fmr1 knockout (KO) mouse and rat models and can indicate cortical hyperexcitability.17–22

Cortical hyperexcitability in FXS likely predisposes individuals with FXS and Fmr1 KO models to seizures. Recently, a longitudinal analysis of a large clinic-based cohort of individuals with FXS showed that the prevalence of having at least one seizure was 12%, and seizures in FXS patients typically started during childhood.9 Numerous laboratories report that juvenile Fmr1 KO mice exhibit audiogenic seizures (AGS) with a high prevalence (generally >60%).23–27 AGS susceptibility decreases with age,24,28 which parallels decreases in seizures with age in FXS.9 AGS, however, are elicited, while spontaneous seizures account for most of the seizures in FXS.9 Recently, we reported that a substantial number of adult Fmr1 KO mice from our colony have unprovoked seizures, and the prevalence was higher in female than male Fmr1 KO mice.29 Intriguingly, a larger percentage of females than males with FXS exhibit seizures for the first time during adulthood and have their last seizures in adulthood.9

Previously, we showed that acute dosing of a novel direct-acting serotonin (5-HT) receptor modulator, (S)-5-(2′-fluorophenyl)-N,N-dimethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-amine (FPT), prevented AGS in 100% of juvenile Fmr1 KO mice, and enhanced social approach behavior, decreased anxiety-like behaviors, and decreased repetitive behaviors in several strains of mice.28,30 Our initial pharmacological investigations revealed that FPT is a potent (low nM), high-efficacy 5-HT1A receptor (5-HT1AR) partial agonist and a potent, low-efficacy 5-HT7R partial agonist.28,30 We have continued systematic pharmacological characterization of FPT and report herein our latest observations that FPT is a potent and efficacious agonist at 5-HT1B and 5-HT1DRs, but not 5-HT1FRs. These discoveries were motivating, as several papers have reported that 5-HT1BR activation enhances social behavior in various mouse models of ASD,31,32 and activation of 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, or 5-HT1DRs has anticonvulsant effects in seizure models.33–35 Furthermore, the genes encoding 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, and 5-HT1DRs are differentially expressed in the absence of FMRP—the protein lost due to FMR1 inactivation that causes FXS—in either human brain organoids or fetal brain tissue.3

Herein, we tested the effects of an acute subcutaneous 5.6 mg/kg dose of FPT—an optimal dose determined from our previous studies28,30—on non-task-related, cortical EEG in freely moving adult Fmr1 KO mice compared to control conspecific (wildtype, WT) mice. The primary objectives of this study were to evaluate FPT’s effects as well as sex and genotype effects on cortical EEG spectra, specifically measured above the somatosensory and auditory cortices. We hypothesized that adult Fmr1 KO mice would have EEG abnormalities, particularly an enhancement in relative gamma-band power, that might reflect their spontaneous seizure phenotype and that FPT would correct their EEG abnormalities. Furthermore, since FXS symptomology differs between males and females,36,37 and since we have observed sex differences in AGS and spontaneous seizures in Fmr1 KO mice,28,29 we hypothesized there would be sex differences in relative EEG power.

RESULTS

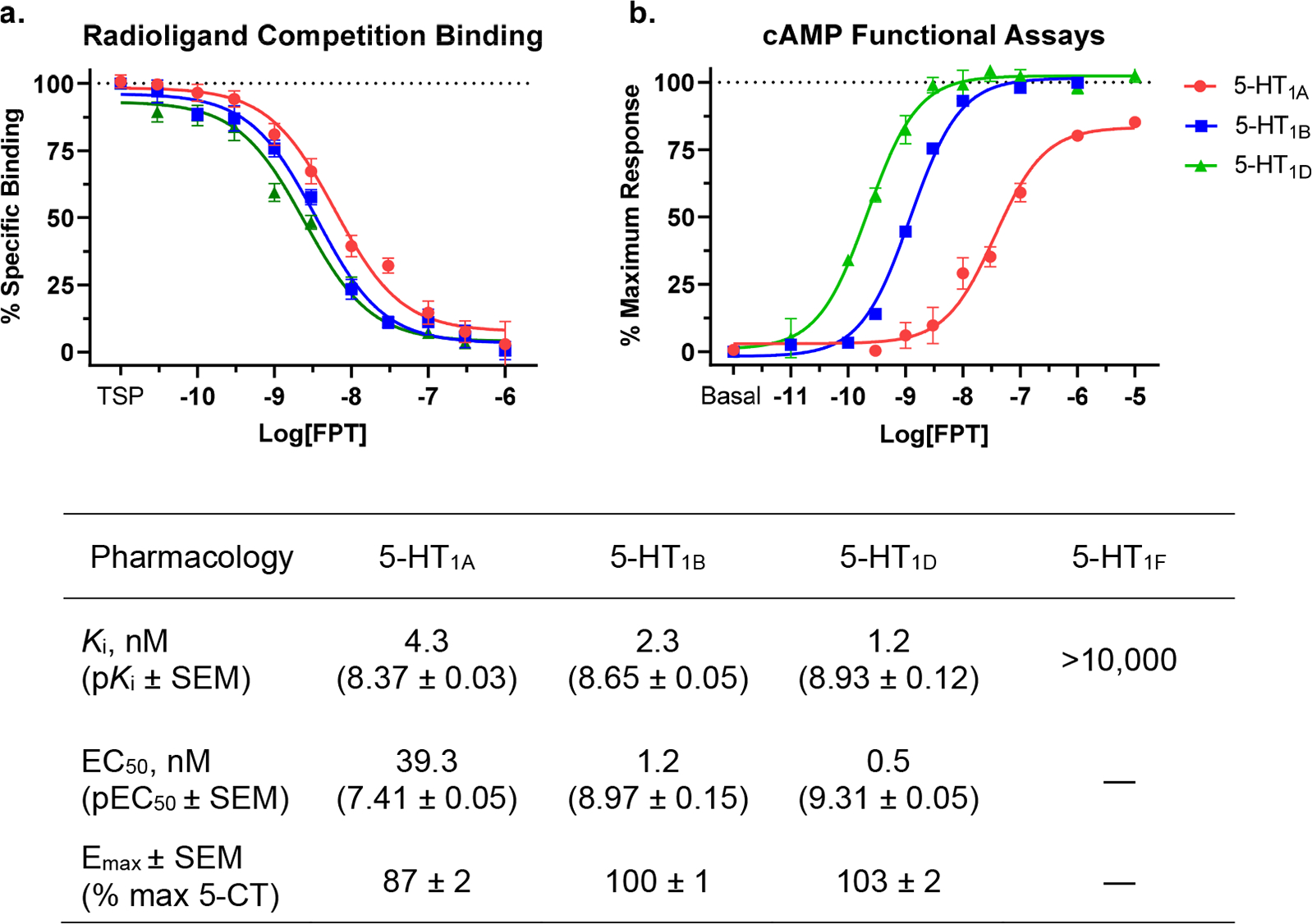

In Vitro Pharmacology of FPT (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(a, b) In vitro pharmacology of FPT at human 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, and 5-HT1FRs. Note that FPT was a full agonist at 5-HT1B and 5-HT1DRs and a high-efficacy, partial agonist at 5-HT1ARs, as determined by efficacies to decrease cAMP levels relative to 5-CT. FPT’s rank order of potency, including its binding affinities as determined in competition binding assays with [3H]5-CT and its EC50 values in cAMP assays, was 5-HT1D > 5-HT1B > 5-HT1A. FPT showed nil affinity at 5-HT1FRs, so we did not test its functional activity at them. The table at the bottom of the figure summarizes the pharmacological observations. TSP, total specific binding/no compound present.

We evaluated FPT’s affinity (Figure 1a), potency, and efficacy (Figure 1b) at 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, and 5-HT1DRs and its affinity at 5-HT1FRs. FPT was a potent and efficacious partial agonist at 5-HT1ARs, consistent with our previous reports.28,30 At 5-HT1B and 5-HT1DRs, FPT was a potent, full-efficacy agonist. The affinity of FPT at 5-HT1FRs was greater than 10 μM, so we concluded it had nil activity and therefore did not evaluate its functional activity at 5-HT1FRs. Results, including affinities obtained from radioligand competition binding assays (Ki values) and functional activities obtained from cAMP assays (EC50 and EMAX), are summarized in a table under Figure 1. For radioligand competition binding assays with [3H]5-CT, the average (±SEM) total specific binding, as counts per minute, was 513 (±48), 702 (±40), and 563 (±17) for 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, and 5-HT1DRs, respectively; for [3H]5-HT at 5-HT1FRs, total specific binding was 7040 (±214). Given the low variability of [3H]5-CT binding sites between 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, and 5-HT1DRs across multiple transfections, we conclude that receptor density differences did not strongly influence the relative EC50 and EMAX values we obtained in functional assays.

In Vivo EEG.

Effects of Genotype and Sex at Baseline (Figure 2). Relative Delta Power.

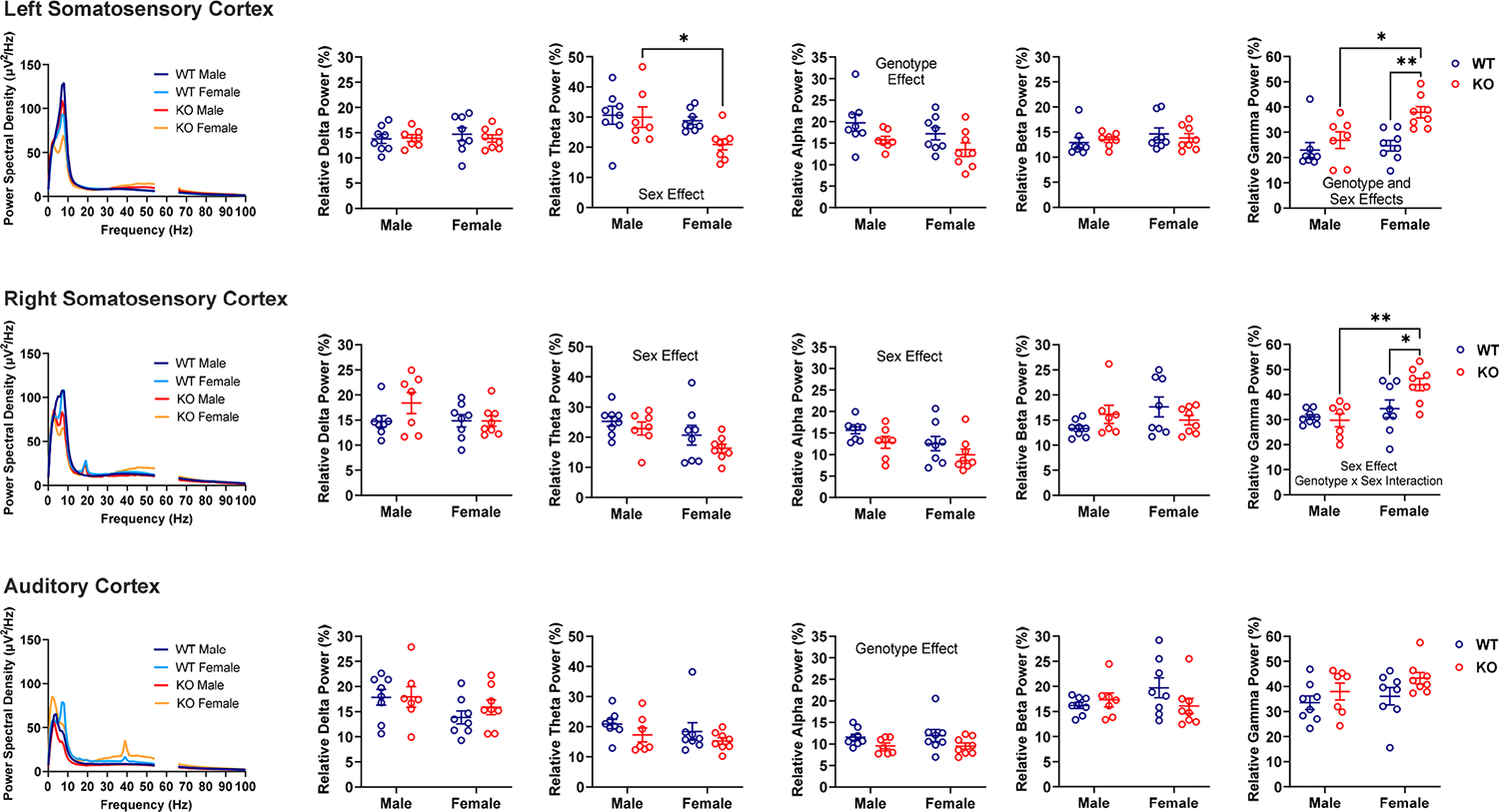

Figure 2.

Effects of genotype and sex on relative EEG power in male and female WT and Fmr1 KO mice at baseline. Power spectral density (leftmost column) shows absolute power per frequency. Scatter dot plots show relative power. Significant (P < 0.05) main effects are written on the graphs. Note there were region-dependent genotype effects on relative alpha (Fmr1 KO < WT) and gamma (Fmr1 KO > WT) power, and there were region-dependent sex effects on relative theta (female < male), alpha (female < male), and gamma (female > male) power. There was also a genotype-by-sex interaction on relative gamma power (higher power observed in female Fmr1 KO). Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 show significant results from Šídák’s multiple comparisons tests.

Across all neural systems, there were no significant interactions and no main effects of genotype or sex on relative delta power. There was only a trend for a sex effect on relative delta power recorded above the auditory cortex [F (1, 27) = 3.640, P = 0.0671], which accounted for 11.56% of the measured variation; females tended to exhibit lower delta power.

Relative Theta Power.

For the left somatosensory cortex, there was a main effect of sex [F (1, 27) = 4.931, P = 0.0350] on theta power, which accounted for the largest percentage (13.18%) of total measured variation. Multiple comparisons showed that Fmr1 KO females had lower relative theta power than Fmr1 KO males (P = 0.0316). There was also a trend toward a genotype effect [F (1, 27) = 3.047, P = 0.0922] on relative theta power, which female Fmr1 KO mice drove. For the right somatosensory cortex, there was a main effect of sex [F (1, 27) = 6.267, P = 0.0186] on relative theta power, and sex accounted for the largest percentage (17.42%) of the total measured variation. Multiple comparisons only showed a trend toward lower theta power in Fmr1 KO females compared to males (P = 0.0996). For the auditory cortex, there were no significant interactions and no main effects of genotype or sex on theta power.

Relative Alpha Power.

For the left somatosensory cortex, there was a main effect of genotype on relative alpha power [F (1, 27) = 6.280, P = 0.0185], with genotype accounting for the largest percentage (17.45%) of the total measured variation. Multiple comparisons tests did not reveal genotype differences (P > 0.15), but Fmr1 KO mice tended to exhibit lower relative alpha power. For the right somatosensory cortex, there was a main effect of sex on relative alpha power [F (1, 27) = 4.981, P = 0.0341]; sex accounted for the largest percentage of the total measured variation in alpha power (13.71%). Multiple comparisons did not reveal significant sex differences between males and females, but females tended to have lower alpha power. There was also a trend for a genotype effect [F (1, 27) = 4.028, P = 0.0549], where Fmr1 KO tended to show lower relative alpha power. For the auditory cortex, there was a main effect of genotype on the alpha band [F (1, 27) = 5.664, P = 0.0246], accounting for 17.29% of the measured variability. Multiple comparisons did not reveal genotype differences (P > 0.14), but Fmr1 KO mice tended to exhibit lower alpha power.

Relative Beta Power.

For the right somatosensory cortex, there was a trend toward a sex-by-genotype interaction on beta power [F (1, 27) = 3.683, P = 0.0656], which accounted for the majority of the measured variability (11.49%); female WT mice tended to have higher beta power than male WT mice (P = 0.0757), whereas the converse was observed for the Fmr1 KO mice. The sharp peaks in absolute power at ~20 Hz recorded above the right somatosensory cortex were likely artifacts, as they occurred in most groups, irrespective of genotype and sex, except for WT male mice. Also, the peaks from each group closely overlapped, and there is evidence that such peaks are related to motor responses.38 However, since we screened every video to remove EEG blips associated with noticeable muscle jerks and twitches, and yet these peaks remained, we decided we did not have sufficient reason to remove them. For the left somatosensory cortex and auditory cortex, there were no significant interactions, and no main effects of genotype or sex on beta power.

Relative Gamma Power.

For the left somatosensory cortex, there was a main effect of genotype [F (1, 27) = 10.36, P = 0.0033]; genotype accounted for the largest percentage (22.14%) of total measured variation in gamma power, and Fmr1 KO mice exhibited higher gamma power. There was also a main effect of sex [F (1, 27) = 5.713, P = 0.0241]; female mice exhibited higher relative gamma power. Multiple comparison tests showed that Fmr1 KO females exhibited higher relative gamma power compared to WT females (P = 0.0027) and Fmr1 KO males (P = 0.0154). The higher gamma power in female Fmr1 KO mice accounted for a trend toward a genotype x sex interaction [F (1, 27) = 3.060, P = 0.0916]. For the right somatosensory cortex, there was a main effect of sex on gamma power [F (1, 27) = 11.78, P = 0.0019], accounting for most of the measured variability (25.53%), and a significant genotype-by-sex interaction [F (1, 27) = 4.517, P = 0.0429]. Multiple comparison tests showed that Fmr1 KO females exhibited higher relative gamma power compared to WT females (P = 0.0232) and Fmr1 KO males (P = 0.0013). For the auditory cortex, there was only a trend toward a genotype effect [F (1, 27) = 3.765, P = 0.0629] on relative gamma power, which accounted for 11.44% of the total measured variability; Fmr1 KO mice tended to have higher gamma power. The sharp peaks in absolute power at ~40 Hz recorded above the auditory cortex of female mice were likely artifacts due to external auditory stimuli.17

Effects of Genotype, Sex, And Treatment (Figure 3). Relative Delta Power.

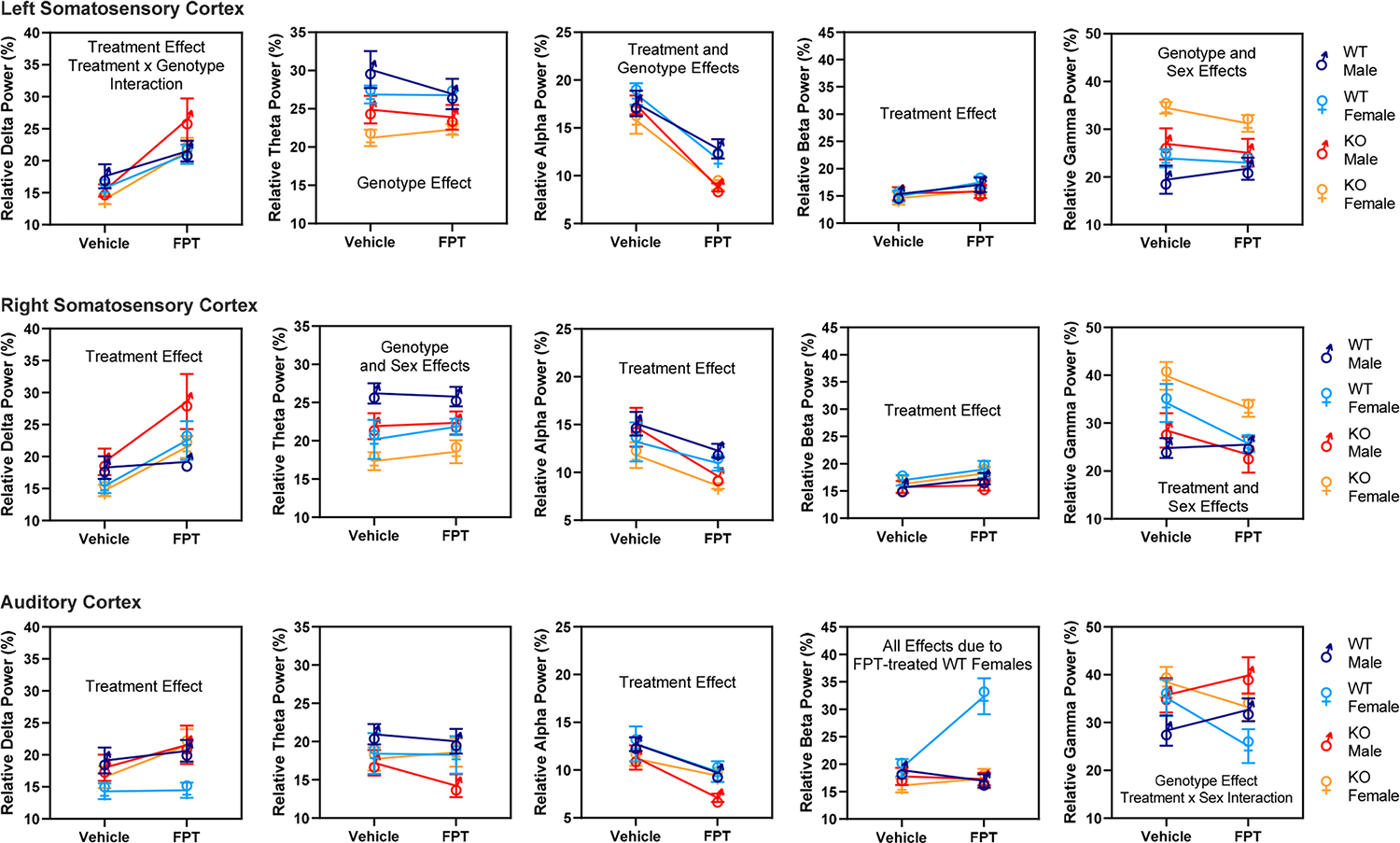

Figure 3.

Effects of genotype, sex, and treatment—vehicle compared to FPT—on relative EEG power in male and female WT and Fmr1 KO mice. For clarity, only significant (P < 0.05) main effects are written on the graphs. Notably, FPT significantly increased relative delta and beta power recorded above the somatosensory cortices and decreased relative alpha power recorded above the somatosensory and auditory cortices. FPT decreased relative gamma power in the right somatosensory cortex in most groups. Note also that where FPT had significant effects, they tended to be more robust in Fmr1 KO than in WT mice. Data were analyzed by repeated measures three-way ANOVA. Results from Fisher’s LSD multiple comparisons tests are reported in the Results section.

Averaging across channels, FPT accounted for the largest percentage of measured variation in relative delta power (19.28%). For the left somatosensory cortex, there was a main effect of treatment [F (1, 27) = 53.04, P < 0.0001] and a treatment-by-genotype interaction [F (1, 27) = 6.029, P = 0.02]. Multiple comparison tests showed that, relative to vehicle, FPT increased relative delta power in male and female WT mice (P = 0.046 and P = 0.009, respectively). FPT also increased delta power in male and female Fmr1 KO mice (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.004, respectively). The treatment-by-genotype interaction appeared to be caused by FPT producing a more statistically significant effect in Fmr1 KO mice. For the right somatosensory cortex, there was a main effect of treatment [F (1, 27) = 17.62, P = 0.0003]. There were no interactions, though there was a trend toward a sex-by-genotype interaction (P = 0.07). Multiple comparison tests showed that relative to vehicle, FPT increased relative delta power in female WT mice (P = 0.018) and male and female Fmr1 KO mice (P = 0.004 and P = 0.02, respectively). For the auditory cortex, there was a main effect of treatment [F (1, 27) = 6.642, P = 0.016]. There were no other significant effects, though there was a trend toward a main effect of sex (P = 0.08) and a treatment-by-genotype interaction (P = 0.096). Multiple comparison tests showed that, relative to vehicle, FPT increased delta power only in female Fmr1 KO mice (P = 0.017) and showed a trend to increase delta power in the male Fmr1 KO mice (P = 0.098).

Relative Theta Power.

Averaging across channels, genotype accounted for the largest percentage of measured variation in relative theta power (13.28%). For the left somatosensory cortex, there was a main effect of genotype [F (1, 27) = 11.76, P = 0.002]. There was a trend toward a treatment-by-sex interaction (P = 0.094). Multiple comparison tests showed vehicle-treated male Fmr1 KO had significantly lower relative theta power than vehicle-treated male WT mice (P = 0.02). There were similar significant differences between vehicle-treated female Fmr1 KO and vehicle-treated female WT mice (P = 0.01) and FPT-treated female Fmr1 KO compared to FPT-treated female WT mice (P = 0.04). For the right somatosensory cortex, there was a main effect of genotype [F (1, 27) = 6.178, P = 0.02] and a main effect of sex [F (1, 27) = 10.78, P = 0.003]. Multiple comparison tests showed a trend toward lower relative theta power in vehicle-treated male Fmr1 KO compared to vehicle-treated male WT mice (P = 0.06). Regarding sex effects, relative theta power was significantly lower in vehicle-treated WT female compared to vehicle-treated WT male mice (P = 0.008), and in vehicle-treated Fmr1 KO female compared to vehicle-treated Fmr1 KO male mice (P = 0.049). For the auditory cortex, there were no main effects of genotype, sex, or treatment on relative theta power. There were also no significant interactions.

Relative Alpha Power.

Averaging across channels, FPT accounted for the largest percentage of measured variation in relative alpha power (32.36%). For the left somatosensory cortex, there were main effects of treatment [F (1, 27) = 130.4, P < 0.0001] and genotype [F (1, 27) = 8.483, P = 0.007]. Multiple comparison tests showed that FPT, relative to vehicle, significantly decreased relative alpha power in all groups: WT males (P = 0.003), WT females (P < 0.0001), Fmr1 KO males (P < 0.0001), and Fmr1 KO females (P < 0.0001). Regarding genotype comparisons, FPT-treated male Fmr1 KO mice exhibited significantly lower relative alpha power compared to FPT-treated male WT mice (P = 0.008). Vehicle-treated female Fmr1 KO showed a trend of exhibiting lower relative alpha power compared to vehicle-treated female WT mice (P = 0.058). Similarly, FPT-treated female Fmr1 KO showed a trend of exhibiting lower relative alpha power than FPT-treated female WT mice (P = 0.061). For the right somatosensory cortex, there was a main effect of treatment [F (1, 27) = 21.3, P < 0.0001] and a trend toward a main effect of sex (P = 0.098). Multiple comparison tests showed that, relative to the respective vehicle control group, FPT significantly decreased alpha power in male and female Fmr1 KO mice (P = 0.002 and P = 0.03, respectively) and showed a trend to decrease relative alpha power in male WT mice (P = 0.059). For the auditory cortex, there was a main effect of treatment [F (1, 27) = 48.78, P < 0.0001). Multiple comparison tests showed that FPT, relative to vehicle, significantly decreased relative alpha power in all groups: WT males (P = 0.001), WT females (P = 0.002), Fmr1 KO males (P < 0.0001), and Fmr1 KO females (P = 0.043).

Relative Beta Power.

Averaging across channels, FPT accounted for the largest percentage of measured variation in relative beta power (5.208%). For the left somatosensory cortex, there was a main effect of treatment [F (1, 27) = 6.845, P = 0.014]. Multiple comparisons revealed that, relative to vehicle, FPT significantly increased relative beta power in WT female mice (P = 0.03). For the right somatosensory cortex, there was a main effect of treatment [F (1, 27) = 4.545, P = 0.0423]. Multiple comparison tests did not show any significant effects between groups. For the auditory cortex, there were main effects of every source that were driven by results from FPT-treated female WT mice. The main effects were treatment [F (1, 27) = 10.24, P = 0.0035], genotype [F (1, 27) = 10.10, P = 0.0037], sex [F (1, 27) = 5.651, P = 0.0248], a treatment-by-genotype interaction [F (1, 27) = 7.839 P = 0.0093], a treatment-by-sex interaction [F (1, 27) = 20.41, P = 0.0001], a genotype-by-sex interaction [F (1, 27) = 8.461, P = 0.0072], and a treatment-by-genotype-by-sex interaction [F (1, 27) = 12.91, P = 0.0013]. Multiple comparisons tests showed that FPT significantly increased relative beta power in female WT mice compared to all other groups: vehicle-treated female WT mice (P < 0.0001), FPT-treated male WT mice (P < 0.0001), FPT-treated male Fmr1 KO mice (P < 0.0001), and FPT-treated female Fmr1 KO mice (P < 0.0001).

Relative Gamma Power.

Averaging across channels, genotype accounted for the largest percentage of measured variation in relative gamma power (13.12%). For the left somatosensory cortex, there were main effects of genotype [F (1, 27) = 12.87, P = 0.0013] and sex [F (1, 27) = 5.492, P = 0.0267] and a trend toward a treatment-by-genotype interaction [F (1, 27) = 3.241, P = 0.083]. Multiple comparisons showed that vehicle-treated male and female Fmr1 KO mice had significantly higher relative gamma power than their respective WT controls (P = 0.0247 and 0.0014, respectively). Regarding the sex effect, compared to vehicle-treated male Fmr1 KO mice, vehicle-treated female Fmr1 KO mice showed significantly higher relative gamma power (P = 0.0239). For the right somatosensory cortex, there were main effects of treatment [F (1, 27) = 8.608, P = 0.0068] and sex [F (1, 27) = 12.35, P = 0.0016]. Multiple comparisons showed that FPT, relative to vehicle, significantly decreased relative gamma power in female Fmr1 KO mice (P = 0.0487). Similarly, relative to vehicle, FPT significantly decreased gamma power in female WT mice (P = 0.0155). Regarding the sex effect, vehicle-treated female WT mice had significantly higher relative gamma power than vehicle-treated male WT mice (P = 0.0169). Similar sex effects were observed in vehicle-treated Fmr1 KO mice (P = 0.0057) and the FPT-treated Fmr1 KO mice (P = 0.0176). For the auditory cortex, there were main effects of genotype [F (1, 27) = 4.769, P = 0.038] and a treatment-by-sex interaction [F (1, 27) = 17.43, P = 0.0003]. Multiple comparisons showed a trend toward higher relative gamma power in FPT-treated female Fmr1 KO compared to FPT-treated female WT mice (P = 0.0825). Regarding the treatment-by-sex interaction, FPT showed a trend to increase relative gamma power in male mice and had the converse effect in female mice. One significant effect was FPT decreased relative gamma power in female WT mice (P = 0.0013).

To test if the treatment effects we observed were affected by somatosensory stimulation from injections, we examined if there were any differences between the baseline and vehicle conditions. In the WT group, vehicle injections resulted in a statistically significant decrease in relative theta power in the left somatosensory cortex [t(7)=3.169, P = 0.0157, paired t test, data not shown]. No differences were observed in the Fmr1 KO group.

Pharmacokinetics and Residual Effects of FPT.

For our within-subject study design, subjects that received vehicle on day 1 received FPT on day 2 (~24 h later), and subjects that received FPT on day 1 received vehicle on day 2. To determine if FPT had persistent effects on EEG spectra, we tested if mice that received FPT on day 1 had significantly different baseline EEG spectra on the next day of testing. In the WT group, no significant differences in relative power were found between day 1 (pre-FPT) and day 2 (post-FPT) baselines (data not shown). In the Fmr1 KO group, compared to pre-FPT, post-FPT baseline theta was decreased in the left somatosensory cortex [t(7)=2.840, P = 0.025, paired t test], and alpha was increased in the left [t(7)=4.937, P = 0.002] and right [t(7)=7.837, P = 0.0001] somatosensory cortices (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we further characterized the pharmacology of FPT by determining its activity at human 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, and 5-HT1F receptors, compared to its activity at 5-HT1ARs. In addition to its potent agonist activity at 5-HT1ARs, which aligned with our previous observations,28,30 FPT was a potent, full agonist at 5-HT1B and 5-HT1DRs; it had nil activity at 5-HT1FRs. We also evaluated EEG power, recorded above the somatosensory and auditory cortices in freely moving adult male and female WT and Fmr1 KO mice, at baseline, after vehicle injection, and after an acute injection of a behaviorally active dose of FPT. We tested EEG activity in mouse subjects during a narrow age range (P94–99). Because we observed that spontaneous seizures in our Fmr1 KO mice occur most frequently during this period,29 we hypothesized we would detect alterations in their cortical EEG power that might reflect their seizure propensity.

We observed an increase in relative gamma (30–100 Hz) power measured above the left somatosensory cortex in adult female Fmr1 KO mice, compared to WT mice during baseline recordings; we also observed this effect in female and male Fmr1 KO mice in the vehicle treatment group condition. The high relative gamma-band power in male Fmr1 KO was like what others have reported.39 Considering sex effects, female Fmr1 KO exhibited higher relative gamma power at baseline and after vehicle injection than male Fmr1 KO mice. Most EEG studies report that males but not females—humans with FXS and Fmr1 KO mice—show increased gamma power,18,37 though there are notable exceptions wherein researchers have not observed an increase in cortical gamma power in male Fmr1 KO mice and rats.18,40 Nonetheless, increased gamma power can reflect neuronal hyperexcitability,41 and our findings of increased gamma power in adult female compared to male Fmr1 KO mice parallel our observations of an increased prevalence of spontaneous seizures in adult female compared to male Fmr1 KO.29 We observed that ~46% of adult female and ~15% of adult male Fmr1 KO mice from our colony exhibit spontaneous seizures in their home cages during the age range wherein we recorded cortical EEG.29 Since others have not reported the spontaneous seizure phenotype yet have observed increases in gamma power in Fmr1 KO mice, gamma power increases likely do not fully account for the spontaneous seizure phenotype. Since we did not control for phases of the estrous cycle in female mice, we cannot make conclusions about hormonal contributions to the sex differences we observed.

In contrast to previous findings that reported higher cortical theta (4–8 Hz) power in Fmr1 KO mice,11,12,37 we observed a decrease in relative theta power in the somatosensory cortex in Fmr1 KO at baseline and after vehicle injection. We also observed a sex effect on theta power in the somatosensory cortex, with female Fmr1 KO mice showing lower relative theta power than male Fmr1 KO mice. This finding is consistent with another preclinical study that showed reduced relative theta power in female Fmr1 KO rats.18 Clinical studies show decreased cortical alpha (8–13 Hz) power in FXS,11,12,14,16 which is similar to our observations of small, but significant, decreases in relative alpha power at baseline in the left somatosensory cortex and auditory cortex in Fmr1 KO mice. Other studies report no alterations in alpha power in Fmr1 KO subjects.22,40,42–46 The discrepancies could reflect differences in test subject histories and differences in set and setting. In summary, at baseline or after vehicle injections, we observed increased relative gamma power and decreased theta and alpha power in the somatosensory cortex in adult Fmr1 KO mice. We also observed a general tendency for females to exhibit more pronounced increases in gamma and decreases in theta and alpha than males. Finally, genotype effects detected from recordings above the left and right somatosensory cortices, such as increased relative gamma power in Fmr1 KO mice, were dampened or absent in the auditory cortex, like previous observations in adult mice.22

FPT reduced gamma power recorded above the right somatosensory cortex, but we did not observe a genotype effect of increased gamma above the right somatosensory cortex in untreated Fmr1 KO mice. FPT had a sex-dependent impact on gamma power in the auditory cortex, where it increased power in males but decreased power in females. We have not yet tested if FPT’s powerful anticonvulsant effects in juvenile Fmr1 KO mice persist in adult animals, but FPT did not reduce excessive relative gamma power recorded above the left somatosensory cortex in adult Fmr1 KO mice; this result is reminiscent of other medication candidates for FXS. The GABAB agonist, baclofen, and the GABAA positive allosteric modulator, BAER-10140, although effective at preventing AGS in Fmr1 KO mice, do not, in most studies, correct the elevations in cortical gamma power in Fmr1 KO mice.42,47,48,53 Thus, with the major caveat of age as a confounding variable—AGS were tested in juvenile mice, and EEG was recorded in adult mice—the elevated cortical gamma power phenotype in adult Fmr1 KO mice does not appear, at present, to reflect susceptibility to AGS. As AGS emanate predominantly from the inferior colliculus, the excessive cortical gamma power in Fmr1 KO mice may be a neurophysiological alteration independent of AGS.27

FPT robustly increased relative delta (0.5–4 Hz) and decreased relative alpha power across all channels, with more pronounced effects in Fmr1 KO mice. Notably, delta oscillations are associated with attention and decision-making processes.49,50 Like FPT, baclofen, which has shown some efficacy in treating FXS and ASD,51,52 increases delta power in both WT and Fmr1 KO mice.53 Decreases in slow wave delta power have been reported in Fmr1 KO rats.18 Therefore, FPT’s effect of increasing delta power might benefit patients with FXS. However, others report increases in delta power in Fmr1 KO mice19 and patients with FXS,14 so it is difficult to make conclusions about the impacts on delta power. There are also irregularities regarding cortical alpha power. Lower alpha power correlates with greater social impairment, increased hypersensitivity to sensory stimuli, and decreased inhibition of gamma waves in FXS.12 Still, others show that lower alpha power is associated with higher full-scale IQ in ASD.54 FPT also increased relative beta (13–30 Hz) power across channels, irrespective of genotype. FPT’s effects on relative beta power were comparatively modest, with one anomaly; FPT had an uncharacteristically large effect of increasing beta power in the auditory cortex of WT females. We do not have sufficient information to make conclusions about this effect. Compared to typically developing controls, FXS patients show a decrease in relative beta power; males show a reduction in low beta (13–20 Hz) power, whereas females show a reduction in low and high beta (20.5–30 Hz) power.16 We believe it is also important to note that alterations in cortical EEG spectra observed in patients with FXS and ASD could be related to their medications, their cognitive and emotional states and the setting during testing, or compensatory neural processing.

Despite inconsistencies regarding resting-state EEG power observations in the context of FXS, there are more evident effects of psychoactive medications on cortical EEG power. The psychotomimetic NMDA receptor antagonist, MK-801, increases alpha power,55 and FPT attenuates the behavioral effects of MK-801 in mice.30 The glycine transporter-1 inhibitor, SSR504734, which, like FPT, shows preclinical neurotherapeutic effects—including reversing MK-801-induced hyperactivity—suppresses MK-801-induced increases in alpha power; SSR504734 also reduces alpha-band power at baseline.55 Similarly, centrally acting muscarinic receptor antagonists that cause cognitive impairments and at high doses are psychotomimetic, increase alpha power, and potentiating muscarinic receptor activity, via acetylcholinesterase inhibition, positive allosteric modulation, or direct agonism counteract this effect;56 direct-acting muscarinic receptor agonists also decrease baseline alpha power.57 The decrease in alpha power may be a biomarker that translates clinically, as a recent phase 3 clinical trial showed that a centrally acting muscarinic receptor agonist effectively treats schizophrenia.58 Also, clinical studies consistently show that single-dose administration of the prototypical, second-generation antipsychotic, clozapine, which has unique and relatively low activity at dopamine D2 receptors,59 reduces alpha power;60 clozapine also suppresses MK-801-elicited increases in alpha power.55 Other FDA-approved neuropsychiatric medications, including the new antidepressant allopregnanolone, which acts as a GABAA positive allosteric modulator, decrease alpha power and increase beta power, as we observed with FPT.61 Therefore, FPT’s effect of lowering relative alpha power and increasing relative beta power might be pharmacotherapeutic for FXS patients, especially patients with psychotic and depressive symptoms.62,63 Furthermore, these points illustrate that there might be convergent effects on EEG power of neurotherapeutic medications with different mechanisms of action.

Evaluations of FPT’s pharmacology at human 5-HT1-type receptors showed that it is a potent near-full agonist at 5-HT1A receptors and a potent full agonist at 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors. Recently, we showed that selective 5-HT1AR activation prevents audiogenic seizures in Fmr1 KO mice,64 and 5-HT1AR agonists can have procognitive, memory-enhancing effects.65 Other studies show that 5-HT1B receptor activation enhances social behaviors and social memory.31,32 These observations support the hypothesis that FPT’s prosocial and anticonvulsant effects28 are likely mediated by the activation of 5-HT1-type receptors. However, its activity at 5-HT728 or undiscovered targets may also contribute to its effects. Since we did not measure EEG during behavioral or cognitive tasks, we cannot link FPT’s effects on relative EEG power to its distinct behavioral effects. We observed that FPT did not have residual effects on baseline EEG the day after it was administered to WT mice, yet we observed a rebound increase in relative alpha power in Fmr1 KO mice, suggestive of a compensatory change after pharmacokinetic elimination of FPT. Previously, we reported that, after peripheral administration to WT mice, FPT readily enters the brain, reaching maximal levels in 90 min, at which point they begin to wane.30

There is scant knowledge about the impact of 5-HT1Rs on cortical EEG activity recorded from the scalp. Preclinical studies report that nonselective 5-HT1AR agonists like buspirone (which also binds dopamine D2 and other receptors) and 8-OH-DPAT (which also activates 5-HT7Rs) slow theta activity and increase alpha power; however, recordings were from electrodes implanted into the sensorimotor cortex.66 5-HT1A/1BR agonists, such as CGS-12066B, dose-dependently decrease power spectral density, especially in the alpha and beta frequency ranges.67 More recently, a cortical EEG study in rats showed that the modestly selective 5-HT1AR agonist, flesinoxan,65 increases 18–30 Hz beta power and 30–50 Hz gamma power.68 FPT showed similar effects on EEG as the entactogen, prosocial drug MDMA, which has powerful serotonin-releasing effects. In drug-naïve human subjects, MDMA decreases alpha and increases beta power; however, unlike FPT, MDMA decreases delta and theta power, likely mediated by a combination of its serotonin-, dopamine-, and norepinephrine-releasing effects.69

Shortcomings of this study include limited analyses of the EEG data. Resting-state studies can capture aspects of EEG patterns in FXS patients other than power.12,13 Also, we did not separate the mobile and immobile phases of the EEG data; however, previous reports suggest that gamma differences between Fmr1 KO mice and WT mice persist independent of locomotion.19,22 We examined video recordings and observed that none of the mouse subjects slept or moved excessively during EEG recordings. We also removed several wave distortions associated with grooming and muscle twitching (see the Methods section for more details) before analyzing the data. We only tested FPT at a single, relatively high dose and during the light cycle of the mice (when they are typically sleeping). Given the polypharmacology of FPT, lower doses of FPT or repeated administration of FPT may lead to differential engagement of targets resulting in different EEG outcomes, which could be affected by circadian factors. Group numbers were 7–8, and increasing group sizes would likely have decreased variability in the data. A shortcoming in our conclusions about FPT’s effect on alpha waves is that the alpha waves we decoded could be mu waves present over the sensorimotor cortex.70 Suppression of mu waves is associated with the mirroring of actions, language, and empathy, and mu suppression appears disrupted in ASD and psychosis.71–73 However, examining such changes and the impact of FPT on them would require task-related, stimulus-induced EEG. Therefore, the decrease in relative power in the frequency range of 8–13 Hz caused by FPT needs further investigation. Finally, the effects of compounds, including FPT, on EEG power could be epiphenomena unrelated to their therapeutic benefits. Additional studies are required to further advance the field of pharmaco-EEG in psychiatry.

In summary, we observed sex differences in Fmr1 KO mice which pointed toward a more hyperexcitable state in female Fmr1 KO mice that might contribute to their susceptibility to spontaneous seizures.29 FPT, a highly potent and efficacious 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, and 5-HT1DR agonist, increased relative cortical delta power, did not significantly affect theta power, robustly decreased alpha power, modestly increased beta power, and had mixed effects on relative gamma power in adult mice. In addition to these findings, collectively, we have observed that FPT is an efficacious partial agonist at 5-HT1AR, a weak agonist at 5-HT7R, and a full agonist at 5-HT1BR and 5-HT1DR, with >10–10 000-fold selectivity over 5-HT1F, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C, α1A, α1B, H1, and D2 receptors, and FPT shows in vivo efficacy as an antiepileptic in Fmr1 knockout mice and has anxiolytic-like and prosocial effects in Fmr1 knockout mice and other mouse models.28,30 Future experiments aim to link FPT’s complex pharmacology to its neurophysiological and neurobehavioral effects. Evaluating brain waves after treatment with various subtype-selective 5-HTR ligands in conjunction with behavioral tests would help elucidate EEG signatures that may be useful biomarkers for FXS, and results would help guide the development of medication candidates with sharply defined polypharmacology.

METHODS

In Vitro Pharmacology.

Cell Culture and Transfections.

Human embryonic kidney 293t cells (HEK293t, ATCC no. CRL3216) were used to express human 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, and 5-HT1F receptors. All cells were grown in 10 cm cell-culture treated plates in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% carbon dioxide. The cells were fed Corning Cellgro Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, MT-10–013) supplemented with 10% regular fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (complete growth medium). cDNA encoding the wildtype 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, and 5-HT1FR was obtained from UMR cDNA Resource Center (Rolla, MO). Transfections were performed on HEK293t cells at less than pass 20 and ~80% confluency. Cells were washed with 1 mL 1× phosphate buffered saline and incubated for 48 h in a bath containing 10 μg of cDNA, 40 μL of polyethylenimine transfection reagent (Thermo Scientific, BMS1003-A), 3 mL of Opti-MEM (Gibco, ref. 31985–070), and 3 mL of complete growth medium.

Receptor Affinity Assays.

Radioligand competition assays to determine ligand affinities were performed following established methods.74 48 h after transfection, cells were collected in 25 mL of wash buffer (50 mM tris-HCl, 4 °C, pH = 7.4) and centrifuged at 12 000g at 4 °C for 10 min. Next, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was homogenized in wash buffer using 50 pumps of a handheld tissue grinder. The suspension was then centrifuged in 25 mL of wash buffer under the same conditions; this was repeated once more so that each preparation underwent three rounds of centrifugation. Following the last centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded, and the membrane pellet was frozen at −80 °C. On experimental days, standard binding buffer (50 mM tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 mM EDTA, pH = 7.4) was added to membrane pellets, and the membrane was homogenized. Ligand test concentrations spanned 10 half-log units. Serotonin, 10 μM, was used to define nonspecific binding of the 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, and 5-HT1DR agonist radiolabel [3H]5-carboxamidotryptamine ([3H]5-CT; 0.6–1 nM; 37.7 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA). For 5-HT1FR, LY334370, 10 μM, was used for nonspecific binding of the agonist radiolabel [3H]5-HT (5–7 nM; 45.6 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston MA). Experiments were performed in a total well volume of 250 μL, with 3–10 μg of protein per well. Following a 90 min incubation with the assay plate covered at room temperature shaking at 300 rpm, the assay was terminated by rapid vacuum filtration through Whatman GF/B fired filters (Brandel Inc., Gaithersburg, MD), presoaked with cold wash buffer, using an automated Tomtec Harvester 96 instrument (Hamden, CT). Filters were rewashed before being dried and then saturated with a scintillation cocktail (Scintiverse BD, Fisher Chemical, Fair Lawn, NJ). Scintillations were detected by a Tri-Carb 2910 TR liquid scintillation analyzer (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA). At least three independent assays, with ligands tested in triplicate or greater, were conducted (i.e., N ≥ 9 data points per concentration were collected).

Receptor Function Assays.

The potency (EC50) and efficacy (Emax) of FPT at 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, and 5-HT1DRs were assessed using PerkinElmer’s LANCE Ultra cAMP immunoassay. All functional assays were conducted according to the manufacturers’ guidelines in 384-well plates. 5-CT, a 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, and 5-HT1DR receptor full efficacy agonist was used to calculate Emax. After the cells were transfected, the medium was aspirated, and cells were washed with PBS. Cells were then incubated with ligands in serum-free buffer (5 mM HEPES, 1× HBSS, 0.1% BSA) containing 0.5 mM IBMX at 37 °C for 2 h with ~1500 cells and 0.3 μM forskolin (EC90) for tests at 5-HT1A and 5-HT1DRs and ~3500 cell and 3.0 μM forskolin for tests at 5-HT1B receptors. cAMP was detected using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek Boston, MA). Each compound was assessed at 10 concentrations in triplicate in at least three independent assays (i.e., N ≥ 9 individual data points per concentration were collected).

In Vivo EEG.

Subjects.

The Mercer University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all experimental protocols involving mice. All experimental procedures were performed following the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, eighth edition. FVB.129P2-Pde6b+ Tyrc-ch Fmr1tm1Cgr/J (Fmr1 KO, JAX stock 004624) and FVB.129P2-Pde6b+ Tyrc-ch/AntJ (WT control conspecifics, JAX stock 004828), procured from the Jackson Laboratory, were bred, housed, and genotyped as previously described.28 Pups were weaned at postnatal day (P) 21 ± 1, and all mice were group-housed by sex and genotype (N = 2–4 per cage) until the day of cranial surgery. Mice were maintained on a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle at a temperature of 73 ± 2 °F and relative humidity of 50 ± 5%, with food and water available ad libitum. A total of 32 adult—age P94–P99 during EEG testing—experimentally naïve mice were tested. These included 16 WT controls (8 male and 8 female) and 16 Fmr1 KO mice (8 male and 8 female). One male Fmr1 KO mouse was excluded from analyses since it had a seizure during EEG recording,29 leaving seven male Fmr1 KO mice in the study.

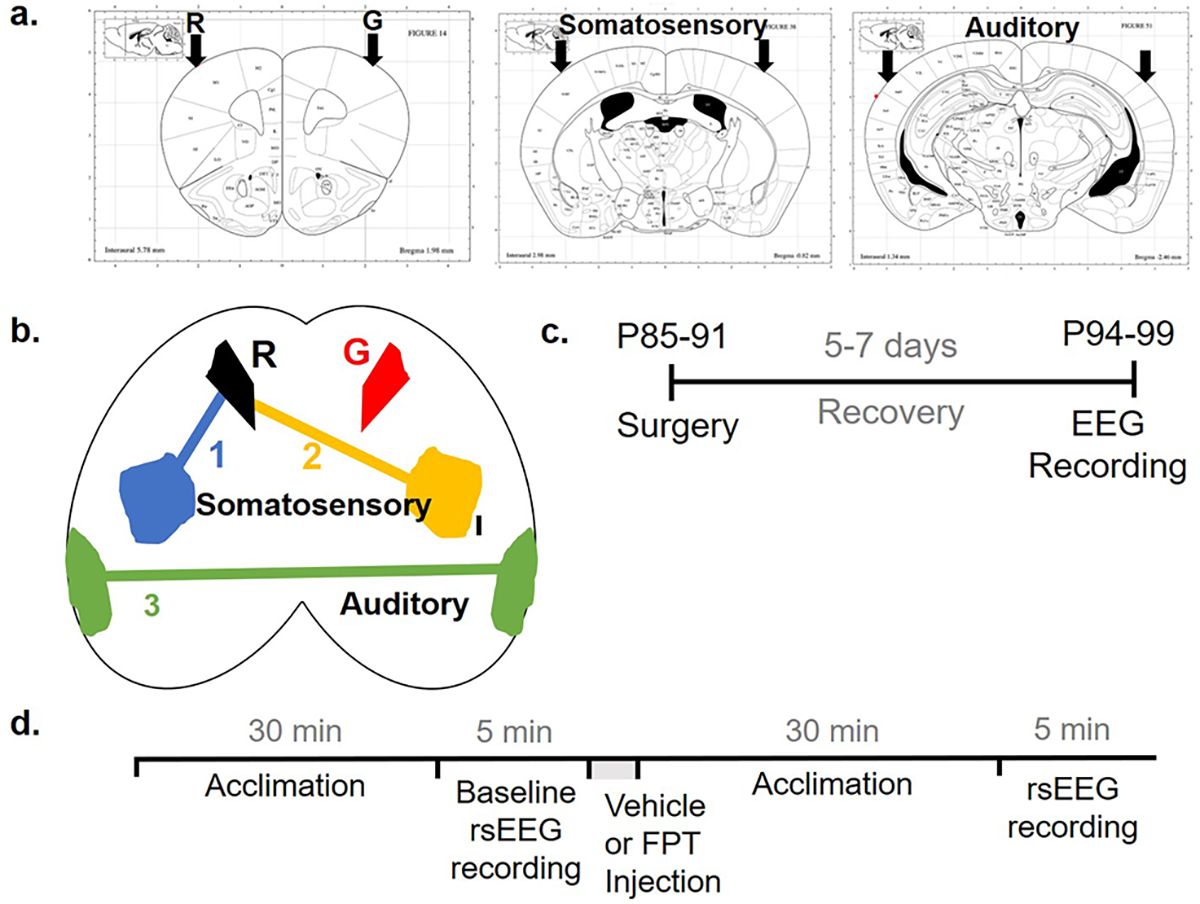

Surgery (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

EEG surgery coordinates and timelines. Electrode coordinates and channels are shown in coronal (a) and axial (b) planes. Timeline for surgery (c) and recording (d) of non-task-related, resting-state (rs) EEG. R, reference electrode; G, ground electrode.

Mice were anesthetized using 2.5% isoflurane and maintained at ~1.5% isoflurane throughout the surgical procedures. Mice were placed on a heating pad and the antibiotic, cefazolin sodium, 10 mg/kg, was administered subcutaneously (s.c.), followed by the application of Puralube eye ointment (Dechra Pharmaceuticals). Betadine solution was applied topically on shaved heads, and a rostrocaudal incision was made using a sterile scalpel. Coordinates for motor cortex [anteroposterior (AP) + 1.79 mm with respect to bregma, mediolateral (ML) ± 1.65 mm with respect to bregma], primary somatosensory/barrel cortex (AP − 0.89 mm, ML ± 2.44 mm), and secondary auditory cortex (AP − 3.27 mm, ML ± 4.00 mm) were marked on the cranium using a robot stereotaxic (Neurostar); coordinates were based on the mouse brain atlas by Paxinos and Franklin (Figure 4a,b). These regions for recording EEG were chosen based on previous reports of increased density of immature spines in the barrel and somatosensory cortices and hyper-responsive neurons in the auditory cortex.75–78 Holes of ~700 μm were drilled into the markings by twisting in a sterile 23G needle. Six sterile 0.1 in. mouse screws-with-wire-leads (Pinnacle Technology) were implanted epidurally and fixed using dental acrylic. The wires-leads from screws were soldered with a 6-pin surface headmount (Pinnacle Technology) using a tin wire. The electrodes in the motor cortex were designated as ground and common reference, and those in the somatosensory and auditory cortices were recording electrodes. A topical antibiotic was applied on the head around the dental acrylic casing; incised tissue was glued together using Vetbond tissue glue (3M). Mice recovered after surgery on a heating pad in a clean cage. After recovery, each mouse was housed individually, and the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory carprofen, 5 mg/kg, was administered s.c. daily for 5 days. After a five-to-seven-day recovery period, EEG data were recorded during the lights-on cycle (Figure 4c). Body weight, appearance, activity level, and general motor behavior were documented before and after surgery and on the day of recording.

Data Acquisition.

EEG recordings were performed as previously described19 (Figure 4d). Briefly, mice were acclimated to the recording room for 10 min in their home cages, followed by a 15 min acclimation to the recording chamber (240 mm diameter, clear Plexiglas bowl, with a layer of clean bedding). The headmount was then connected to a preamplifier attached to a commutator swivel under brief (<30 s) isoflurane anesthesia followed by another 15 min of acclimation. A 5 min baseline EEG was then recorded using a 3-channel tethered EEG system (Pinnacle Technology) and Sirenia Acquisition software 2.0.6 with a sampling rate of 2 kHz, 0.5 Hz high pass filter, and 100 Hz low pass filter. Vehicle (Milli-Q water, Millipore Sigma) or FPT, 5.6 mg/kg, was injected s.c. 30 min after the injection, EEG was recorded for another 5 min. The same mice were used the next day for a different treatment to minimize interindividual variability; mice that received vehicle on the first day received FPT on the second and vice versa. A top-mounted camera captured videos of mice during the EEG recording sessions. All recordings were performed between 10 am and 7 pm.

Since recording electrodes were implanted above the somatosensory and auditory cortices, we tried to minimize unnecessary stimuli that would elicit large potentials in these regions during EEG recordings. Somatosensory stimuli were minimized by providing subjects the same bedding in the recording chamber as in their home cages and regulating temperature and humidity in the testing room (72 °F and 50%, respectively) compared to the colony room (73 °F and 46%). Acclimation and recordings were performed in a quiet room with sound levels lower than the colony room (~61 dB), with only one experimenter (TSS). For all trials combined, sound levels in the test room during acclimation (mean ± SEM = 43.1 ± 0.3 dB) and recording (44.3 ± 0.3 dB) were consistent; dB were measured by a sound-level meter/data logger, REED Model SD-4023, placed next to the recording chamber.

Data Analyses.

All experimental data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 9.0 or a higher version (La Jolla, CA). Results with P < 0.05 were considered significant for all experiments. We also considered P values of 0.051–0.099 as trends. All data are shown as mean ± SEM.

In Vitro Pharmacology.

Results for binding assays were fitted with the one-site Ki nonlinear regression model. Results for functional assays were normalized to basal signaling (0%) and 10 μM 5-CT response (100%) and fitted with log(agonist) vs response (3 parameters).

In Vivo EEG.

EEG analyses were performed as previously described.29 Briefly, raw EEG recording files were converted to EDF files in Sirenia and imported into Python 3.6 using the open-source pyedf library. First, we matched video and EEG recordings and deleted EEG artifacts associated with muscle and head twitches, grooming, hiccups, scratching near the headmount, digging, and sudden jerks while rearing. We also deleted huge spike trains and wave distortions. Then, EEG signals were uniformly truncated for the maximum duration of the recordings, and power spectral density was calculated and graphed as a Welch plot using the scipy fft packages to obtain fast Fourier transforms. The area under the curve of the Welch plot was used to calculate absolute power in each frequency band—delta (0.5–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–13 Hz), beta (13–30 Hz), and gamma (30–55 Hz and 65–100 Hz). Frequencies between 55 and 65 Hz were eliminated as line noise. To minimize interindividual variability in absolute power, we used relative power per frequency band as the outcome measure.11,12,18,79 Relative power was calculated as the percentage of absolute power in a frequency band in one channel divided by the total absolute power in that channel. 2-way ANOVA analyzed baseline spectral EEG data to test for genotype and sex effects. Šídák’s multiple comparisons were performed to compare groups. Separately, data from each EEG spectral band obtained after vehicle and FPT treatment were analyzed by repeated measures 3-way ANOVA to test for treatment, genotype, and sex effects. We planned multiple comparisons between groups a priori, so these were performed using Fisher’s LSD test. We also evaluated if the first injection affected relative power in the somatosensory cortex by using paired t tests comparing baseline EEG data and EEG data recorded after the injection of vehicle on day 1. Furthermore, we evaluated, using within-subject, paired t tests, whether FPT had residual effects on EEG; this was done by comparing day 1 and day 2 baselines of mice that received FPT on day 1.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.2c00574

Contributor Information

Tanishka S. Saraf, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, Mercer University, Atlanta, Georgia 30341, United States

Ryan P. McGlynn, Center for Drug Discovery, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, and Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Northeastern University, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, United States

Omkar M. Bhatavdekar, Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland 21218, United States

Raymond G. Booth, Center for Drug Discovery, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, and Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Northeastern University, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, United States

Clinton E. Canal, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, Mercer University, Atlanta, Georgia 30341, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Deng PY; Klyachko VA Channelopathies in fragile X syndrome. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 2021, 22, 275–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Van der Aa N; Kooy RF GABAergic abnormalities in the fragile X syndrome. Eur. J. Paediatr Neuro 2020, 24, 100–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Kang Y; Zhou Y; Li Y; Han Y; Xu J; Niu W; Li Z; Liu S; Feng H; Huang W; Duan R; Xu T; Raj N; Zhang F; Dou J; Xu C; Wu H; Bassell GJ; Warren ST; Allen EG; Jin P; Wen Z A human forebrain organoid model of fragile X syndrome exhibits altered neurogenesis and highlights new treatment strategies. Nature Neuroscience 2021, 24, 1377–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Luque MA; Beltran-Matas P; Marin MC; Torres B; Herrero L Excitability is increased in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells of Fmr1 knockout mice. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0185067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Gildin L; Rauti R; Vardi O; Kuznitsov-Yanovsky L; Maoz BM; Segal M; Ben-Yosef D Impaired Functional Connectivity Underlies Fragile X Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Contractor A; Klyachko VA; Portera-Cailliau C Altered Neuronal and Circuit Excitability in Fragile X Syndrome. Neuron 2015, 87, 699–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Hagerman RJ; Berry-Kravis E; Hazlett HC; Bailey DB Jr.; Moine H; Kooy RF; Tassone F; Gantois I; Sonenberg N; Mandel JL; Hagerman PJ Fragile X syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis Primers 2017, 3, 17065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Kaufmann WE; Kidd SA; Andrews HF; Budimirovic DB; Esler A; Haas-Givler B; Stackhouse T; Riley C; Peacock G; Sherman SL; Brown WT; Berry-Kravis E Autism Spectrum Disorder in Fragile X Syndrome: Cooccurring Conditions and Current Treatment. Pediatrics 2017, 139, S194–S206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Consortium. Seizures in Fragile X Syndrome: Associations and Longitudinal Analysis of a Large Clinic-Based Cohort. Front Pediatr 2021, 9, 736255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Erickson CA; Davenport MH; Schaefer TL; Wink LK; Pedapati EV; Sweeney JA; Fitzpatrick SE; Brown WT; Budimirovic D; Hagerman RJ; Hessl D; Kaufmann WE; Berry-Kravis E Fragile X targeted pharmacotherapy: lessons learned and future directions. J. Neurodev Disord 2017, 9, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Van der Molen MJ; Van der Molen MW Reduced alpha and exaggerated theta power during the resting-state EEG in fragile X syndrome. Biol. Psychol 2013, 92, 216–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Wang J; Ethridge LE; Mosconi MW; White SP; Binder DK; Pedapati EV; Erickson CA; Byerly MJ; Sweeney JA A resting EEG study of neocortical hyperexcitability and altered functional connectivity in fragile X syndrome. J. Neurodev Disord 2017, 9, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Wilkinson CL; Nelson CA Increased aperiodic gamma power in young boys with Fragile X Syndrome is associated with better language ability. Mol. Autism 2021, 12, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Proteau-Lemieux M; Knoth IS; Agbogba K; Cote V; Biag HMB; Thurman AJ; Martin CO; Belanger AM; Rosenfelt C; Tassone F; Abbeduto LJ; Jacquemont S; Hagerman R; Bolduc F; Hessl D; Schneider A; Lippe S EEG Signal Complexity Is Reduced During Resting-State in Fragile X Syndrome. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12, 716707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Ethridge LE; De Stefano LA; Schmitt LM; Woodruff NE; Brown KL; Tran M; Wang J; Pedapati EV; Erickson CA; Sweeney JA Auditory EEG Biomarkers in Fragile X Syndrome: Clinical Relevance. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience 2019, 13, 00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Smith EG; Pedapati EV; Liu R; Schmitt LM; Dominick KC; Shaffer RC; Sweeney JA; Erickson CA Sex differences in resting EEG power in Fragile X Syndrome. J. Psychiatr Res. 2021, 138, 89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kozono N; Okamura A; Honda S; Matsumoto M; Mihara T Gamma power abnormalities in a Fmr1-targeted transgenic rat model of fragile X syndrome. Sci. Rep 2020, 10, 18799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Wong H; Hooper AWM; Niibori Y; Lee SJ; Hategan LA; Zhang L; Karumuthil-Melethil S; Till SM; Kind PC; Danos O; Bruder JT; Hampson DR Sexually dimorphic patterns in electroencephalography power spectrum and autism-related behaviors in a rat model of fragile X syndrome. Neurobiol Dis 2020, 146, 105118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Lovelace JW; Ethell IM; Binder DK; Razak KA Translation-relevant EEG phenotypes in a mouse model of Fragile X Syndrome. Neurobiol Dis 2018, 115, 39–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Jonak CR; Lovelace JW; Ethell IM; Razak KA; Binder DK Multielectrode array analysis of EEG biomarkers in a mouse model of Fragile X Syndrome. Neurobiol Dis 2020, 138, 104794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Lovelace JW; Rais M; Palacios AR; Shuai XS; Bishay S; Popa O; Pirbhoy PS; Binder DK; Nelson DL; Ethell IM; Razak KA Deletion of Fmr1 from Forebrain Excitatory Neurons Triggers Abnormal Cellular, EEG, and Behavioral Phenotypes in the Auditory Cortex of a Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome. Cereb Cortex 2020, 30, 969–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Wen TH; Lovelace JW; Ethell IM; Binder DK; Razak KA Developmental Changes in EEG Phenotypes in a Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome. Neuroscience 2019, 398, 126–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Chen L; Toth M Fragile X mice develop sensory hyperreactivity to auditory stimuli. Neuroscience 2001, 103, 1043–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Musumeci SA; Bosco P; Calabrese G; Bakker C; De Sarro GB; Elia M; Ferri R; Oostra BA Audiogenic seizures susceptibility in transgenic mice with fragile X syndrome. Epilepsia 2000, 41, 19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Saraf TS; Felsing DE; Armstrong JL; Booth RG; Canal CE Evaluation of lorcaserin as an anticonvulsant in juvenile Fmr1 knockout mice. Epilepsy Res. 2021, 175, 106677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Westmark PR; Gutierrez A; Gholston AK; Wilmer TM; Westmark CJ Preclinical testing of the ketogenic diet in fragile X mice. Neurochem. Int. 2020, 134, 104687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Gonzalez D; Tomasek M; Hays S; Sridhar V; Ammanuel S; Chang CW; Pawlowski K; Huber KM; Gibson JR Audiogenic Seizures in the Fmr1 Knock-Out Mouse Are Induced by Fmr1 Deletion in Subcortical, VGlut2-Expressing Excitatory Neurons and Require Deletion in the Inferior Colliculus. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 9852–9863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Armstrong JL; Casey AB; Saraf TS; Mukherjee M; Booth RG; Canal CE (S)-5-(2′-Fluorophenyl)-N,N-dimethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-amine, a Serotonin Receptor Modulator, Possesses Anticonvulsant, Prosocial, and Anxiolytic-like Properties in an Fmr1 Knockout Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome and Autism Spectrum Disorder. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020, 3, 509–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Armstrong JL; Saraf TS; Bhatavdekar O; Canal CE Spontaneous seizures in adult Fmr1 knockout mice: FVB.129P2-Pde6b(+)Tyr(c-ch)Fmr1(tm1Cgr)/J. Epilepsy Res. 2022, 182, 106891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Canal CE; Felsing DE; Liu Y; Zhu WY; Wood JT; Perry CK; Vemula R; Booth RG An Orally Active Phenylaminotetralin-Chemotype Serotonin 5-HT7 and 5-HT1A Receptor Partial Agonist That Corrects Motor Stereotypy in Mouse Models. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2015, 6, 1259–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Walsh JJ; Llorach P; Cardozo Pinto DF; Wenderski W; Christoffel DJ; Salgado JS; Heifets BD; Crabtree GR; Malenka RC Systemic enhancement of serotonin signaling reverses social deficits in multiple mouse models for ASD. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021, 46, 2000–2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Mitchell EJ; Thomson DM; Openshaw RL; Bristow GC; Dawson N; Pratt JA; Morris BJ Drug-responsive autism phenotypes in the 16p11.2 deletion mouse model: a central role for gene-environment interactions. Sci. Rep 2020, 10, 12303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Hatini PG; Commons KGA 5-HT1D-receptor agonist protects Dravet syndrome mice from seizure and early death. Eur. J. Neurosci 2020, 52, 4370–4374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Wesolowska A; Nikiforuk A; Chojnacka-Wojcik E Anticonvulsant effect of the selective 5-HT1B receptor agonist CP 94253 in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 541, 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Sourbron J; Lagae L Serotonin receptors in epilepsy: Novel treatment targets? Epilepsia Open 2022, 7, 231–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Rinehart NJ; Cornish KM; Tonge BJ Gender differences in neurodevelopmental disorders: autism and fragile x syndrome. Curr. Top Behav Neurosci 2010, 8, 209–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Smith EG; Pedapati EV; Liu R; Schmitt LM; Dominick KC; Shaffer RC; Sweeney JA; Erickson CA Sex differences in resting EEG power in Fragile X Syndrome. J. Psychiatr Res. 2021, 138, 89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Shackman AJ; McMenamin BW; Slagter HA; Maxwell JS; Greischar LL; Davidson RJ Electromyogenic artifacts and electroencephalographic inferences. Brain Topogr 2009, 22, 7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Razak KA; Binder DK; Ethell IM Neural Correlates of Auditory Hypersensitivity in Fragile X Syndrome. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12, 720752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Pirbhoy PS; Rais M; Lovelace JW; Woodard W; Razak KA; Binder DK; Ethell IM Acute pharmacological inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity during development restores perineuronal net formation and normalizes auditory processing in Fmr1 KO mice. J. Neurochem 2020, 155, 538–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Goswami S; Cavalier S; Sridhar V; Huber KM; Gibson JR Local cortical circuit correlates of altered EEG in the mouse model of Fragile X syndrome. Neurobiol Dis 2019, 124, 563–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Sinclair D; Featherstone R; Naschek M; Nam J; Du A; Wright S; Pance K; Melnychenko O; Weger R; Akuzawa S; Matsumoto M; Siegel SJ GABA-B Agonist Baclofen Normalizes Auditory-Evoked Neural Oscillations and Behavioral Deficits in the Fmr1 Knockout Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome. eNeuro 2017, 4, No. ENEURO.0380–16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Lovelace JW; Ethell IM; Binder DK; Razak KA Translation-relevant EEG phenotypes in a mouse model of Fragile X Syndrome. Neurobiology of Disease 2018, 115, 39–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Lovelace JW; Ethell IM; Binder DK; Razak KA Minocycline Treatment Reverses Sound Evoked EEG Abnormalities in a Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome. Front Neurosci 2020, 14, 771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Jonak CR; Sandhu MS; Assad SA; Barbosa JA; Makhija M; Binder DK The PDE10A Inhibitor TAK-063 Reverses Sound-Evoked EEG Abnormalities in a Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 1175–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Rais M; Lovelace JW; Shuai XS; Woodard W; Bishay S; Estrada L; Sharma AR; Nguy A; Kulinich A; Pirbhoy PS; Palacios AR; Nelson DL; Razak KA; Ethell IM Functional consequences of postnatal interventions in a mouse model of Fragile X syndrome. Neurobiol Dis 2022, 162, 105577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Pacey LK; Heximer SP; Hampson DR Increased GABA(B) receptor-mediated signaling reduces the susceptibility of fragile X knockout mice to audiogenic seizures. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009, 76, 18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Schaefer TL; Ashworth AA; Tiwari D; Tomasek MP; Parkins EV; White AR; Snider A; Davenport MH; Grainger LM; Becker RA; Robinson CK; Mukherjee R; Williams MT; Gibson JR; Huber KM; Gross C; Erickson CA GABAA Alpha 2,3 Modulation Improves Select Phenotypes in a Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 12, 678090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Harmony T The functional significance of delta oscillations in cognitive processing. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience 2013, 7, 00083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Nacher V; Ledberg A; Deco G; Romo R Coherent delta-band oscillations between cortical areas correlate with decision making. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 15085–15090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Berry-Kravis E; Hagerman R; Visootsak J; Budimirovic D; Kaufmann WE; Cherubini M; Zarevics P; Walton-Bowen K; Wang P; Bear MF; Carpenter RL Arbaclofen in fragile X syndrome: results of phase 3 trials. J. Neurodev Disord 2017, 9, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Veenstra-VanderWeele J; Cook EH; King BH; Zarevics P; Cherubini M; Walton-Bowen K; Bear MF; Wang PP; Carpenter RL Arbaclofen in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized, Controlled, Phase 2 Trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 1390–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Jonak CR; Pedapati EV; Schmitt LM; Assad SA; Sandhu MS; DeStefano L; Ethridge L; Razak KA; Sweeney JA; Binder DK; Erickson CA Baclofen-associated neurophysiologic target engagement across species in fragile X syndrome. J. Neurodev Disord 2022, 14, 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Webb SJ; Naples AJ; Levin AR; Hellemann G; Borland H; Benton J; Carlos C; McAllister T; Santhosh M; Seow H; Atyabi A; Bernier R; Chawarska K; Dawson G; Dziura J; Faja S; Jeste S; Murias M; Nelson CA; Sabatos-DeVito M; Senturk D; Shic F; Sugar CA; McPartland JC The Autism Biomarkers Consortium for Clinical Trials: Initial Evaluation of a Battery of Candidate EEG Biomarkers. Am. J. Psychiatry 2022, appiajp21050485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Depoortere R; Dargazanli G; Estenne-Bouhtou G; Coste A; Lanneau C; Desvignes C; Poncelet M; Heaulme M; Santucci V; Decobert M; Cudennec A; Voltz C; Boulay D; Terranova JP; Stemmelin J; Roger P; Marabout B; Sevrin M; Vige X; Biton B; Steinberg R; Francon D; Alonso R; Avenet P; Oury-Donat F; Perrault G; Griebel G; George P; Soubrie P; Scatton B Neurochemical, electrophysiological and pharmacological profiles of the selective inhibitor of the glycine transporter-1 SSR504734, a potential new type of antipsychotic. Neuropsychopharmacology 2005, 30, 1963–1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Kurimoto E; Nakashima M; Kimura H; Suzuki M TAK-071, a muscarinic M1 receptor positive allosteric modulator, attenuates scopolamine-induced quantitative electroencephalogram power spectral changes in cynomolgus monkeys. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0207969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Montani C; Canella C; Schwarz AJ; Li J; Gilmour G; Galbusera A; Wafford K; Gutierrez-Barragan D; McCarthy A; Shaw D; Knitowski K; McKinzie D; Gozzi A; Felder C The M1/M4 preferring muscarinic agonist xanomeline modulates functional connectivity and NMDAR antagonist-induced changes in the mouse brain. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021, 46, 1194–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Brannan SK; Sawchak S; Miller AC; Lieberman JA; Paul SM; Breier A Muscarinic Cholinergic Receptor Agonist and Peripheral Antagonist for Schizophrenia. New Engl J. Med. 2021, 384, 717–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).de Bartolomeis A; Vellucci L; Barone A; Manchia M; De Luca V; Iasevoli F; Correll CU Clozapine’s multiple cellular mechanisms: What do we know after more than fifty years? A systematic review and critical assessment of translational mechanisms relevant for innovative strategies in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Pharmacol Ther 2022, 236, 108236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Mucci A; Volpe U; Merlotti E; Bucci P; Galderisi S Pharmaco-EEG in psychiatry. Clin EEG Neurosci 2006, 37, 81–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Lambert PM; Ni R; Benz A; Rensing NR; Wong M; Zorumski CF; Mennerick S Non-sedative cortical EEG signatures of allopregnanolone and functional comparators. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, in press. DOI: 10.1038/s41386-022-01450-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Keshtkarjahromi M; Palvadi K; Shah A; Dempsey KR; Tonarelli S Psychosis and Catatonia in Fragile X Syndrome. Cureus 2021, 13, e12843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Winarni TI; Schneider A; Ghaziuddin N; Seritan A; Hagerman RJ Psychosis and catatonia in fragile X: Case report and literature review. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2015, 4, 139–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Saraf TS; Yang B; McGlynn RP; Booth RG; Canal CE Targeting 5-HT1A Receptors to Correct Neuronal Hyperexcitability in Fmr1 Knockout Mice. FASEB J. 2022, 36, R4662. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Newman-Tancredi A; Depoortere RY; Kleven MS; Kolaczkowski M; Zimmer L Translating biased agonists from molecules to medications: Serotonin 5-HT1A receptor functional selectivity for CNS disorders. Pharmacol Ther 2022, 229, 107937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Bogdanov NN; Bogdanov MB The role of 5-HT1A serotonin and D2 dopamine receptors in buspirone effects on cortical electrical activity in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 1994, 177, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Bjorvatn B; Ursin R Effects of the selective 5-HT1B agonist, CGS 12066B, on sleep/waking stages and EEG power spectrum in rats. J. Sleep Res. 1994, 3, 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Leiser SC; Pehrson AL; Robichaud PJ; Sanchez C Multimodal antidepressant vortioxetine increases frontal cortical oscillations unlike escitalopram and duloxetine–a quantitative EEG study in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 4255–4272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Frei E; Gamma A; Pascual-Marqui R; Lehmann D; Hell D; Vollenweider FX Localization of MDMA-induced brain activity in healthy volunteers using low resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (LORETA). Hum Brain Mapp 2001, 14, 152–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Garakh Z; Novototsky-Vlasov V; Larionova E; Zaytseva Y Mu rhythm separation from the mix with alpha rhythm: Principal component analyses and factor topography. J. Neurosci Methods 2020, 346, 108892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Bernier R; Dawson G; Webb S; Murias M EEG mu rhythm and imitation impairments in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Brain Cogn 2007, 64, 228–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Oberman LM; Hubbard EM; McCleery JP; Altschuler EL; Ramachandran VS; Pineda JA EEG evidence for mirror neuron dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders. Brain Res. Cogn Brain Res. 2005, 24, 190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Singh F; Pineda J; Cadenhead KS Association of impaired EEG mu wave suppression, negative symptoms and social functioning in biological motion processing in first episode of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2011, 130, 182–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Perry CK; Casey AB; Felsing DE; Vemula R; Zaka M; Herrington NB; Cui M; Kellogg GE; Canal CE; Booth RG Synthesis of novel 5-substituted-2-aminotetralin analogs: 5-HT1A and 5-HT7 G protein-coupled receptor affinity, 3D-QSAR and molecular modeling. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28, 115262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Kazdoba TM; Leach PT; Silverman JL; Crawley JN Modeling fragile X syndrome in the Fmr1 knockout mouse. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2014, 3, 118–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Rais M; Binder DK; Razak KA; Ethell IM Sensory Processing Phenotypes in Fragile X Syndrome. ASN Neuro 2018, 10, 1759091418801092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Rotschafer S; Razak K Altered auditory processing in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Brain Res. 2013, 1506, 12–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Gibson JR; Bartley AF; Hays SA; Huber KM Imbalance of neocortical excitation and inhibition and altered UP states reflect network hyperexcitability in the mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J. Neurophysiol 2008, 100, 2615–2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Nuwer MR Quantitative EEG: I. Techniques and problems of frequency analysis and topographic mapping. J. Clin Neurophysiol 1988, 5, 1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]