Abstract

In recent years, strategies targeting β-cell protection via autoimmune regulation have been suggested as novel and potent immunotherapeutic interventions against type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D). Here, we investigated the potential of toceranib (TOC), a receptor-type tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitor used in veterinary practice, to ameliorate T1D. TOC reversed streptozotocin-induced T1D and improved the abnormalities in muscle and bone metabolism characteristic of T1D. Histopathological examination revealed that TOC significantly suppressed β-cell depletion and improved glycemic control with restoration of serum insulin levels. However, the effect of TOC on blood glucose levels and insulin secretion capacity is attenuated in chronic T1D, a more β-cell depleted state. These findings suggest that TOC improves glycemic control by ameliorating the streptozotocin-induced decrease in insulin secretory capacity. Finally, we examined the role of platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) inhibition, a target of TOC, and found that inhibition of PDGFR reverses established T1D in mice. Our results show that TOC reverses T1D by preserving islet function via inhibition of RTK. The previously unrecognized pharmacological properties of TOC have been revealed, and these properties could lead to its application in the treatment of T1D in the veterinary field.

Keywords: anticancer drug, diabetes mellitus, drug repositioning, tyrosine kinase

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D) is a progressive autoimmune disease caused by genetic and environmental factors [11, 12]. T1D progression is characterized by insulin deficiency and loss of glucose homeostasis due to the destruction of insulin-producing β-cells by β-cell-specific CD8 T cells [5, 12]. The current treatment for T1D in humans and animals is insulin supplementation, and no type of immunotherapy has been established to inhibit the onset and progression of T1D.

Recently, strategies targeting β-cell protection via autoimmune regulation have been suggested as novel and potent immunotherapeutic interventions against T1D [13]. One of the most important of these is signaling via the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/VEGF receptor (VEGFR), a potent angiogenic factor. VEGF enhances angiogenesis and vascular permeability mainly by activating VEGFR-2, which stimulates the migration of immune cells such as T cells and monocytes/macrophages [28]. In fact, VEGF/VEGFR-2 stands out as an important pathway regulating the pathogenesis of inflammatory and immune diseases [30, 35]. Previous reports revealed that VEGF-associated angiogenesis and inflammation decrease the number of β-cells in the pancreas [1, 2]. Consistent with this finding, serum levels of VEGF in T1D patients are significantly higher than those in healthy controls and are positively correlated with elevated HbA1c levels [10]. In addition, VEGFR-2 protein expression and angiogenesis in pancreatic islets are enhanced in patients with T1D [33]. These findings suggest that VEGFR-2-mediated β-cell depletion may contribute to T1D progression. Therefore, agents that regulate VEGF/VEGFR-2 signaling could be novel T1D therapeutics that act via β-cell protection.

Toceranib (TOC) is a receptor-type tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitor designed to target canine malignancies. TOC exerts its antitumor effects by potently inhibiting VEGFR-2 and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) and suppressing angiogenesis in the tumor microenvironment [22, 23]. In this regard, the RTK inhibition profile of TOC raises the possibility that it may be beneficial for the prevention and treatment of T1D. However, the utility of TOC in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases has not been demonstrated, and the effect of TOC on T1D is unknown.

Here, we tested the therapeutic effects of TOC in a mouse model of T1D and identified novel pharmacological properties of TOC in T1D. We showed that TOC prevents the onset of T1D and reverses T1D by improving glucose tolerance associated with β-cell protection. Furthermore, we found that inhibition of PDGFR, a target of TOC, contributed to T1D remission. These results suggest that TOC has promising pharmacological properties as a therapeutic agent for T1D.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Tokyo (approval code P18-131). Male C57BL/6J mice (8–10 weeks) were used in this study. The mice were purchased from Sankyo Labo Service Corp., Inc., Tokyo, Japan and were kept at 22 ± 2°C with a 12 hr light/dark cycle. The mice were allowed ad libitum access to water and standard mouse feed. The experimental procedures using mice were conducted in accordance with the Guide for Animal Experiments of the University of Tokyo.

Induction and evaluation of diabetes

We used streptozotocin (STZ, FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) to prepare a T1D mouse model. Low dose of STZ causes insulitis with the infiltration of T cells, ultimately inducing the destruction of β-cells and hyperglycemia [17]. As in a previous report [32], C57BL/6J mice were injected intraperitoneally (ip) with STZ (50 mg/kg) for 5 consecutive days to induce T1D. Blood samples for blood glucose measurement were collected periodically from the tail vein of the mice. Blood glucose levels were monitored using the LabAssay glucose kit (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical); the onset of T1D was marked by hyperglycemia (>250 mg/dL). Diabetes reversal with treatment was defined as mice with blood glucose levels below 250 mg/dL.

In this study, we set a humane endpoint for the development of T1D: if the rate of weight loss exceeded 20% within a few days after STZ administration, the mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation under deep isoflurane anesthesia.

Drugs and treatments

Toceranib phosphate (TOC; Palladia, Zoetis Animal Health, Madison, NJ, USA) tablets were purchased from Zoetis and were ground and suspended in distilled water to make liquid samples. TOC (0.5 mg/mouse) was administered orally every other day. In experiments to evaluate the onset of T1D, TOC treatment was initiated simultaneously with the administration of STZ. Control mice received the same dose of solvent orally. In experiments to evaluate T1D progression, mice with newly developed T1D (blood glucose levels 250–400 mg/dL) were treated with TOC. In some experiments, mice that were >5 weeks post STZ administration and had blood glucose levels >400 mg/dL were treated similarly.

Crenolanib (CP-868596, MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) was suspended in 0.5% dimethyl sulfoxide. In this study, crenolanib was used as a PDGFRα/β inhibitor, and its dosage was based on a previous report [16]. Mice with newly developed T1D (blood glucose levels 250–400 mg/dL) received crenolanib intraperitoneally daily at 10 mg/kg. Control mice received the same dose of solvent intraperitoneally.

Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry

Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) was performed in accordance with previous reports [19]. The body composition (fat mass, lean mass, and bone mass) of each mouse was measured using a cone beam flat-panel DXA detector (iNSiGHT VET DXA, Osteosys, Korea). Regions of interest (ROIs) were applied to the hind limbs of each mouse, and lean mass and bone mass were calculated for the lower regions of the right and left hind limbs.

Blood chemistry tests

Blood samples for the determination of insulin levels were incubated at room temperature for 2 hr and then centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant obtained by this centrifugation was used as the serum sample. Insulin levels in serum samples were determined using a Mouse Insulin ELISA Kit (10-1247-01, Mercodia, Winston-Salem, NC, USA). The experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunofluorescence

Immunohistochemical staining was performed to assess insulin-producing β-cells in the islets of Langerhans. Pancreatic tissues excised from mice were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. The paraffin-embedded tissues were sliced and subjected to deparaffinization. Antigen retrieval was performed using Tris-EDTA buffer (95°C, 20 min). The tissues were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min to inactivate endogenous peroxidase, followed by incubation with a rabbit anti-insulin antibody (Proteintech, Tokyo, Japan, 1:5,000) at room temperature for 1.5 hr. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline, the specimens were treated with a peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Nichirei Biosciences Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Antibody binding was visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine, and the nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin. The area of insulin-positive β-cells was quantified using the image analysis software Fiji [31].

Statistical analysis

The numerical data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical differences were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t-test for comparisons between two groups and by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s test for comparisons among more than two groups. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05. Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient analysis was used to evaluate the relationships between variables.

RESULTS

Toceranib prevents the development of STZ-induced T1D

First, to determine whether TOC affects the onset and progression of T1D, the blood glucose levels of the mice were followed over time after STZ administration. The blood glucose levels increased in a stepwise manner one week after STZ administration. In contrast, this increase in blood glucose levels was significantly suppressed in mice treated with STZ and TOC (Fig. 1A and 1B). Furthermore, we analyzed individual blood glucose data as an indicator of T1D onset (blood glucose levels >250 mg/dL) and found that all STZ-treated mice developed T1D at 3 weeks after the first dose. In contrast, significantly fewer individuals developed T1D in mice treated with STZ and TOC (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that TOC can prevent the onset of T1D.

Fig. 1.

Toceranib prevents the development of streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes mellitus. (A) and (B) Blood glucose levels after streptozotocin (STZ) administration. Hyperglycemia is a typical metabolic change suggestive of the development of type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D). Changes in blood glucose levels were calculated by the difference between Day 0 and Day 14. Each column shows the mean ± SEM (n=5–7). (C) Individual glucose measurements and percentages of diabetic mice in the STZ-treated (n=5) and STZ+toceranib (TOC)-treated (n=7) groups are shown. TOC administration was started simultaneously with streptozotocin (STZ) administration and continued for 3 weeks. *P<0.05, **P<0.01; significantly different from control mice. #P<0.05, ##P<0.01; significantly different from STZ-treated mice.

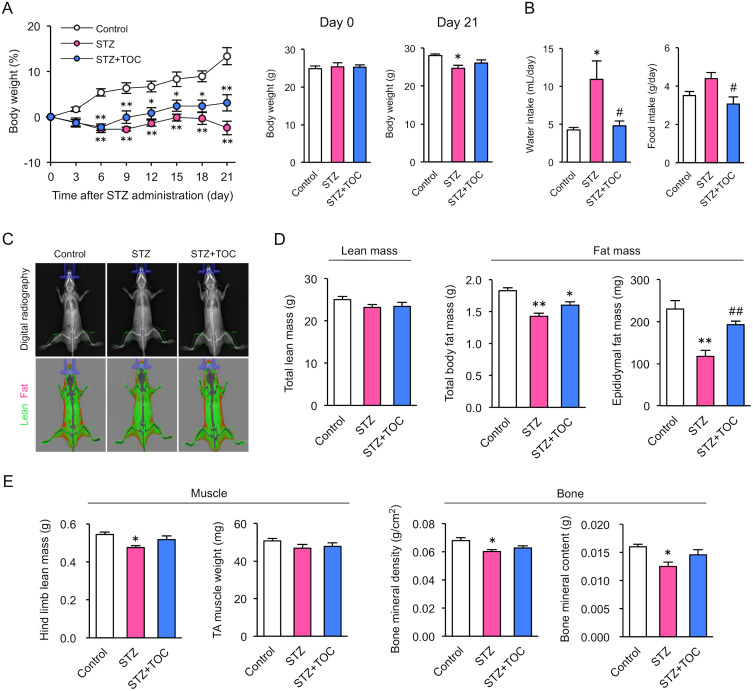

Toceranib improves metabolic abnormalities caused by T1D

Next, we examined whether TOC affects the changes in body composition associated with the development of T1D. T1D mice are characterized by decreased body weight, increased water intake and food intake, and decreased muscle and bone mass. In control mice, body weight increased with growth, while STZ-treated mice gradually lost weight starting 3 days after STZ administration (Fig. 2A). By 3 weeks after STZ treatment, daily water consumption and food intake were significantly lower in mice treated with STZ and TOC than in mice treated with STZ alone (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Toceranib ameliorates type 1 diabetes mellitus-induced abnormalities in body composition. (A) Changes in body weight after streptozotocin (STZ) administration. Each column shows the mean ± SEM (n=5–7). (B) Changes in water intake and food intake after STZ administration. Each column shows the mean ± SEM (n=5–7). (C) Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan images of control, STZ-treated and STZ+toceranib (TOC)-treated mice. DXA can distinguish fat (in red) from non-fat tissues (in green). (D) Total body lean mass and fat mass obtained via DXA. Each column shows the mean ± SEM (n=5–7). (E) Lean mass, bone mineral density and bone mineral content of the hind limbs were obtained via DXA. The data for each sample were calculated by averaging the values for both hind limbs. Each column shows the mean ± SEM (n=5–7). These body composition measurements were conducted on Day 21 after STZ administration. *P<0.05, **P<0.01; significantly different from control. #P<0.05, ##P<0.01; significantly different from STZ-treated mice.

Subsequently, we quantified whole-body body composition using DXA and found that the T1D-induced reduction in fat mass was suppressed in TOC-treated mice (Fig. 2C and 2D). In addition, TOC treatment inhibited T1D-induced reductions in muscle mass and bone mass in the hind limbs and tibia (Fig. 2E). These results suggest that TOC may reduce T1D-induced metabolic abnormalities.

Toceranib preserves islet function in T1D mice

We evaluated insulin secretory capacity, a function of pancreatic islets, to determine whether insulin secretion plays a role in the preventive effect of TOC on the development of T1D. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed a significant reduction in the area of insulin-positive β-cells in the pancreatic islets of STZ-treated mice. However, this decrease was significantly inhibited by TOC treatment (Fig. 3A and 3B). When insulin serum levels were measured in mice 3 weeks after STZ administration, the decrease in serum insulin levels due to T1D was significantly suppressed in TOC-treated mice (Fig. 3C). In addition, Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient analysis was performed to determine the correlation between TOC-induced changes in blood glucose levels and serum insulin levels. The blood glucose levels of mice in this study correlated with their serum insulin levels (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that TOC may improve glycemic control by inhibiting the STZ-induced decrease in insulin secretory capacity.

Fig. 3.

Toceranib prevents the streptozotocin-induced decrease in insulin secretory capacity. (A) Representative images showing insulin-positive cells within pancreatic islets. (B) Quantification of the area ratio of insulin-positive cells within the pancreatic islets. Each column shows the mean ± SEM (n=4). (C) Serum insulin levels on Day 21 after streptozotocin (STZ) administration. Each column shows the mean ± SEM (n=5–7). (D) Correlation between blood glucose and serum insulin levels derived from Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient analysis. **P<0.01; significantly different from control mice. #P<0.05, ##P<0.01; significantly different from STZ-treated mice.

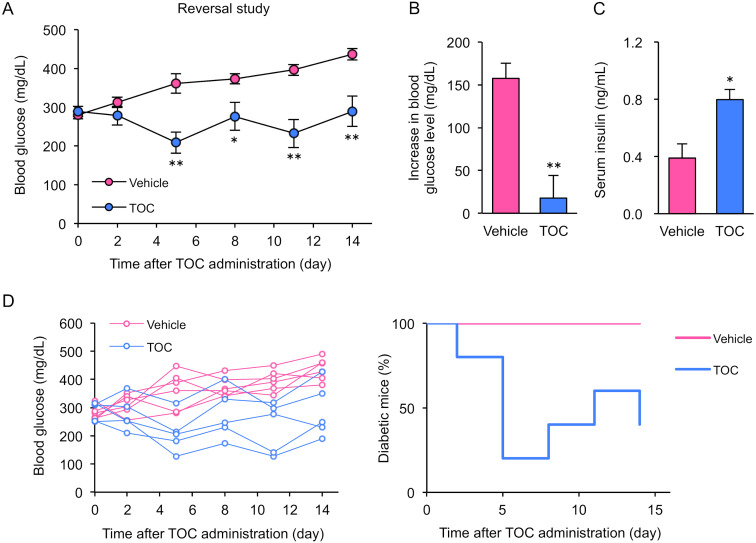

Toceranib reverses established T1D in mice

We focused on the possibility that TOC may reverse T1D by restoring insulin secretion capacity. To investigate whether TOC treatment actually contributes to T1D improvement, we evaluated blood glucose and serum insulin levels after TOC treatment of mice with established T1D. Blood glucose levels in T1D mice increased in a stepwise manner over time. In contrast, this increase in blood glucose levels was significantly suppressed in TOC-treated T1D mice (Fig. 4A and 4B). By 14 days after TOC treatment, serum insulin levels were significantly higher in TOC-treated T1D mice than in T1D mice that did not receive treatment (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, individual blood glucose data were analyzed as an indicator of T1D onset and remission. We found that many TOC-treated mice had remission of T1D, defined as individuals with blood glucose levels below 250 mg/dL (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that TOC reverses T1D by restoring insulin secretion capacity.

Fig. 4.

Toceranib induces remission of established type 1 diabetes mellitus. (A) and (B) Blood glucose levels after toceranib (TOC) treatment. TOC treatment of type 1 diabetic (T1D) mice was initiated at the time of disease onset (blood glucose 250–400 mg/dL) and continued for 2 weeks. Changes in blood glucose levels were calculated by the difference between Day 0 and Day 14. Each column shows the mean ± SEM (n=5–6). (C) Serum insulin levels on Day 14 after TOC treatment. Each column shows the mean ± SEM (n=5–6). (D) Individual glucose measurements and percentages of diabetic mice in the vehicle-treated (n=5) and TOC-treated (n=6) groups are shown. *P<0.05, **P<0.01; significantly different from vehicle-treated mice.

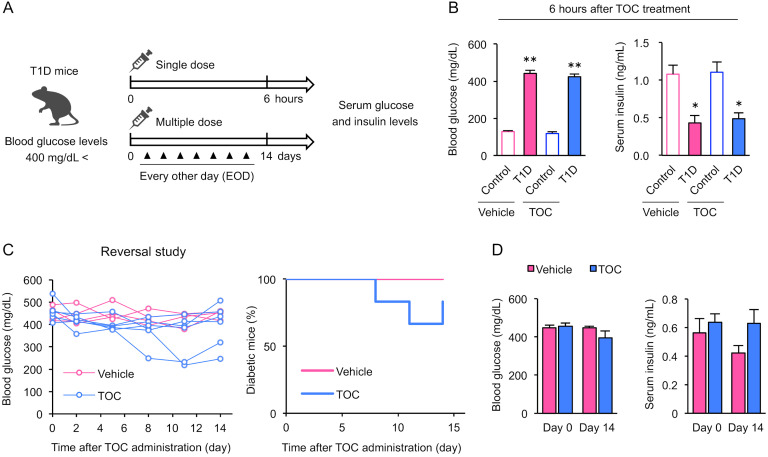

Chronic T1D attenuates the effect of toceranib on blood glucose levels and insulin secretion capacity

Validation using chronic T1D mice, which are in a more β-cell depleted state, is important to determine the appropriate timing of TOC intervention. To determine whether TOC can reverse chronic T1D, we evaluated blood glucose and serum insulin levels after single and multiple doses of TOC to chronic T1D mice (blood glucose levels >400 mg/dL) characterized by β-cell and insulin depletion (Fig. 5A). A single dose of TOC did not affect blood glucose or serum insulin levels (Fig. 5B). Some individuals showed a decrease in blood glucose levels after 14 days of TOC treatment, while many did not show any improvement in T1D (Fig. 5C). At this time, there was no significant difference between blood glucose and serum insulin levels before and after TOC treatment (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that the effect of TOC on blood glucose levels and insulin secretion capacity is attenuated in chronic T1D, a more β-cell depleted state.

Fig. 5.

The effect of toceranib on blood glucose levels and insulin secretion capacity is attenuated in chronic type 1 diabetic mice. (A) Protocols for single and multiple doses of toceranib (TOC) in chronic type 1 diabetic (T1D) mice (blood glucose levels >400 mg/dL) characterized by β-cell and insulin depletion are shown. (B) Blood glucose and serum insulin levels 6 hr after a single dose of TOC. Each column shows the mean ± SEM (n=4–5). (C) TOC treatment of T1D mice was initiated when the chronic course of the disease started (blood glucose >400 mg/dL) and continued for 2 weeks. Individual glucose measurements and percentages of diabetic mice in the vehicle-treated (n=4) and TOC-treated (n=6) groups are shown. (D) Blood glucose and serum insulin levels at the beginning (Day 0) and end (Day 14) of TOC treatment are shown. Each column shows the mean ± SEM (n=4–6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01; significantly different from control mice.

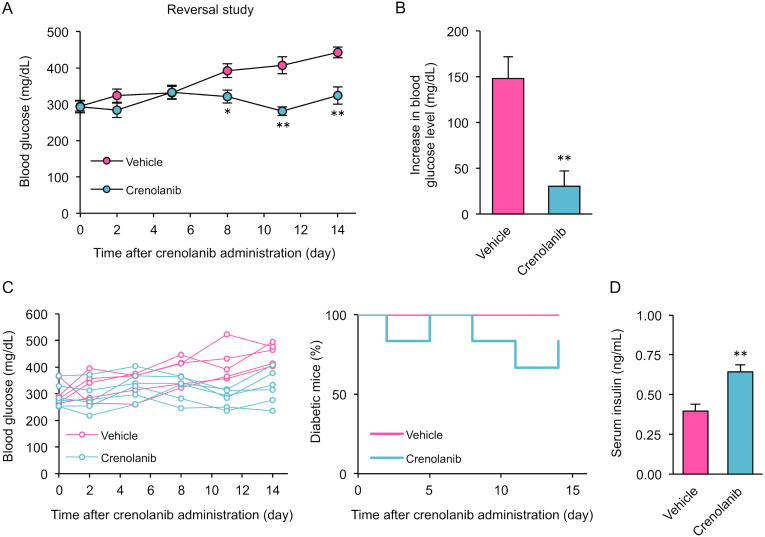

Inhibition of PDGFR reverses established T1D in mice

Finally, to determine whether PDGFR, one of the tyrosine kinase pathways that is potently inhibited by TOC, plays a key role in T1D recovery, we applied crenolanib, a small molecule compound that specifically inhibits PDGFRα/β. Mice treated with crenolanib for 14 days after the onset of T1D had significantly reduced blood glucose levels (Fig. 6A and 6B). Individual blood glucose data indicated that crenolanib induced remission of T1D (Fig. 6C). In addition, serum insulin levels were significantly higher in mice treated with crenolanib than in T1D mice that did not receive treatment (Fig. 6D). These results suggest that inhibition of PDGFR, a target of TOC, contributes to T1D remission.

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor receptor induces remission of established type 1 diabetes mellitus. (A) and (B) Blood glucose levels after crenolanib treatment. Crenolanib treatment of type 1 diabetic (T1D) mice was initiated at the time of disease onset (blood glucose 250–400 mg/dL) and continued for 2 weeks. Changes in blood glucose levels were calculated by the difference between Day 0 and Day 14. Each column shows the mean ± SEM (n=6). (C) Individual glucose measurements and percentages of diabetic mice in the vehicle-treated (n=6) and crenolanib-treated (n=6) groups are shown. (D) Serum insulin levels on Day 14 after crenolanib treatment. Each column shows the mean ± SEM (n=6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01; significantly different from vehicle-treated mice.

DISCUSSION

This is the first report to show that TOC, an anticancer drug used to treat tumors, reverses T1D by improving glucose homeostasis, an effect associated with β-cell protection. T1D remains an intractable disease, and treatment options to restore T1D once it has developed are limited. Our finding that blockade of VEGFR and PDGFR by TOC can reverse T1D suggests that therapies aimed at protecting islets could be a novel therapeutic strategy for T1D.

TOC is one of the RTK inhibitors used in veterinary medicine and has demonstrated clinical activity against many types of tumors, including canine mast cell tumors [21]. RTK inhibitors are emerging as potentially useful in ameliorating autoimmune diseases. In particular, imatinib, which primarily targets c-Abl, has been demonstrated to be effective for treating skeletal muscle dystrophy [18], rheumatoid arthritis [27], autoimmune nephritis [29], and T1D [15, 24] in mouse models. Recently, imatinib has attracted attention as a new therapeutic agent to inhibit the autoimmune destruction of β-cells in T1D, and some clinical trials have been conducted in humans [14]. The improvement of T1D by imatinib is attributed to the reduction of endoplasmic reticulum stress and the protection of β-cells by induction of antioxidant capacity in B lymphocytes via c-Abl inhibition [25, 34].

The present study showed that TOC, which primarily targets VEGFR-2 and PDGFR but not c-Abl, reverses T1D. The inhibition profile of TOC is different from that of imatinib, and the therapeutic effect of TOC is probably due to the protection of β-cells via a different signaling pathway than that of imatinib. This idea is supported by studies showing that blockade of VEGFR activity inhibits T1D-induced islet vasoactivity, impairs T-cell migration to the islets, and improves glycemic control [33]. Our study’s findings suggest that a c-Abl-independent mechanism of action, regulation of angiogenesis by inhibition of VEGFR-2 and PDGFR, is how TOC treats T1D.

VEGF/VEGFR-2 signaling is a master regulator of angiogenesis and vascular permeability and is associated with various chronic inflammatory conditions [26]. Indeed, VEGF mobilizes leukocytes and contributes to inflammation by inducing chemokine expression [6, 20]. Increasing β-cell VEGF-A binding to VEGFR-2 activates islet endothelial cells but leads to β-cell loss [7, 8]. In addition, previous reports have shown that the reduction in islet inflammation in T1D is due to islet vascular remodeling loss due to the inhibition of VEGFR-2 signaling [33]. The β-cell protection conferred by TOC treatment may be attributed to the reduction in islet inflammation due to islet vascular remodeling loss. However, the impact of TOC on the islet vasculature in T1D is unknown, which is a limitation of this study. The role of TOC in islet vascular remodeling requires further investigation.

Our current findings demonstrate that crenolanib, a PDGFRα/β inhibitor, reverses T1D by protecting insulin secretion capacity. Thus, PDGFR signaling, similar to VEGFR-2, could be an important pathway that determines β-cell fate in T1D. PDGF and PDGFR are widely expressed in diverse tissues and are involved in pathological cell growth, including angiogenesis, fibrosis and tumor growth [4]. In addition, given that VEGF is a ligand for PDGFR [3], PDGFR signaling could be activated in T1D and reduce the number of β-cells via islet vascular remodeling. Indeed, previous studies have shown that neutralization of PDGF-BB binding to PDGFRβ reduces blood glucose levels in T1D mice [24]. On the other hand, other studies have reported that increased PDGF-AA/PDGFRα signaling promotes β-cell proliferation [9]. These findings suggest that PDGFRα/β signaling may contribute to recovery and worsening of T1D, respectively. T1D reversal with crenolanib, an inhibitor of PDGFRα/β, could be attributed to the predominant effect of PDGFRβ inhibition. Additional studies on the role of PDGFRα/β in T1D reversal, including subtype classification, are needed since our experiment with crenolanib demonstrated that PDGFR inhibition contributes to T1D reversal. TOC may effectively protect β-cells and improve glycemic control via both VEGFR-2 and PDGFR.

In summary, our results with a mouse model have identified TOC as a drug that reverses T1D via protection of β-cells and suggest that its pharmacological mechanism involves inhibition of VEGFR-2 and PDGFR. Since TOC is commonly used as an anticancer drug in veterinary practice, its clinical application for treating T1D by drug repositioning could be smoothly implemented. TOC may be a new effective therapeutic tool to help prevent and reverse T1D in the veterinary field.

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (24248050 to MH) and a Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (20J11240 to KK).

REFERENCES

- 1.Agudo J, Ayuso E, Jimenez V, Casellas A, Mallol C, Salavert A, Tafuro S, Obach M, Ruzo A, Moya M, Pujol A, Bosch F. 2012. Vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated islet hypervascularization and inflammation contribute to progressive reduction of β-cell mass. Diabetes 61: 2851–2861. doi: 10.2337/db12-0134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akirav EM, Baquero MT, Opare-Addo LW, Akirav M, Galvan E, Kushner JA, Rimm DL, Herold KC. 2011. Glucose and inflammation control islet vascular density and beta-cell function in NOD mice: control of islet vasculature and vascular endothelial growth factor by glucose. Diabetes 60: 876–883. doi: 10.2337/db10-0793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ball SG, Shuttleworth CA, Kielty CM. 2007. Vascular endothelial growth factor can signal through platelet-derived growth factor receptors. J Cell Biol 177: 489–500. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Betsholtz C. 2004. Insight into the physiological functions of PDGF through genetic studies in mice. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 15: 215–228. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bluestone JA, Herold K, Eisenbarth G. 2010. Genetics, pathogenesis and clinical interventions in type 1 diabetes. Nature 464: 1293–1300. doi: 10.1038/nature08933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boulday G, Haskova Z, Reinders ME, Pal S, Briscoe DM. 2006. Vascular endothelial growth factor-induced signaling pathways in endothelial cells that mediate overexpression of the chemokine IFN-gamma-inducible protein of 10 kDa in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol 176: 3098–3107. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.3098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brissova M, Aamodt K, Brahmachary P, Prasad N, Hong JY, Dai C, Mellati M, Shostak A, Poffenberger G, Aramandla R, Levy SE, Powers AC. 2014. Islet microenvironment, modulated by vascular endothelial growth factor-A signaling, promotes β cell regeneration. Cell Metab 19: 498–511. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai Q, Brissova M, Reinert RB, Pan FC, Brahmachary P, Jeansson M, Shostak A, Radhika A, Poffenberger G, Quaggin SE, Jerome WG, Dumont DJ, Powers AC. 2012. Enhanced expression of VEGF-A in β cells increases endothelial cell number but impairs islet morphogenesis and β cell proliferation. Dev Biol 367: 40–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H, Gu X, Liu Y, Wang J, Wirt SE, Bottino R, Schorle H, Sage J, Kim SK. 2011. PDGF signalling controls age-dependent proliferation in pancreatic β-cells. Nature 478: 349–355. doi: 10.1038/nature10502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiarelli F, Spagnoli A, Basciani F, Tumini S, Mezzetti A, Cipollone F, Cuccurullo F, Morgese G, Verrotti A. 2000. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in children, adolescents and young adults with Type 1 diabetes mellitus: relation to glycaemic control and microvascular complications. Diabet Med 17: 650–656. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00350.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiMeglio LA, Evans-Molina C, Oram RA. 2018. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 391: 2449–2462. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31320-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eizirik DL, Colli ML, Ortis F. 2009. The role of inflammation in insulitis and beta-cell loss in type 1 diabetes. Nat Rev Endocrinol 5: 219–226. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gearty SV, Dündar F, Zumbo P, Espinosa-Carrasco G, Shakiba M, Sanchez-Rivera FJ, Socci ND, Trivedi P, Lowe SW, Lauer P, Mohibullah N, Viale A, DiLorenzo TP, Betel D, Schietinger A. 2022. An autoimmune stem-like CD8 T cell population drives type 1 diabetes. Nature 602: 156–161. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04248-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gitelman SE, Bundy BN, Ferrannini E, Lim N, Blanchfield JL, DiMeglio LA, Felner EI, Gaglia JL, Gottlieb PA, Long SA, Mari A, Mirmira RG, Raskin P, Sanda S, Tsalikian E, Wentworth JM, Willi SM, Krischer JP, Bluestone JA. Gleevec Trial Study Group. 2021. Imatinib therapy for patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 9: 502–514. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00139-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hägerkvist R, Sandler S, Mokhtari D, Welsh N. 2007. Amelioration of diabetes by imatinib mesylate (Gleevec): role of beta-cell NF-kappaB activation and anti-apoptotic preconditioning. FASEB J 21: 618–628. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6910com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayashi Y, Bardsley MR, Toyomasu Y, Milosavljevic S, Gajdos GB, Choi KM, Reid-Lombardo KM, Kendrick ML, Bingener-Casey J, Tang CM, Sicklick JK, Gibbons SJ, Farrugia G, Taguchi T, Gupta A, Rubin BP, Fletcher JA, Ramachandran A, Ordog T. 2015. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α regulates proliferation of gastrointestinal stromal tumor cells with mutations in KIT by stabilizing ETV1. Gastroenterology 149: 420–32.e16. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herold KC, Bloch TN, Vezys V, Sun Q. 1995. Diabetes induced with low doses of streptozotocin is mediated by V beta 8.2+ T-cells. Diabetes 44: 354–359. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.3.354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang P, Zhao XS, Fields M, Ransohoff RM, Zhou L. 2009. Imatinib attenuates skeletal muscle dystrophy in mdx mice. FASEB J 23: 2539–2548. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-129833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kishi K, Goto M, Tsuru Y, Hori M. 2023. Noninvasive monitoring of muscle atrophy and bone metabolic disorders using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in diabetic mice. Exp Anim 72: 68–76. doi: 10.1538/expanim.22-0097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee TH, Avraham H, Lee SH, Avraham S. 2002. Vascular endothelial growth factor modulates neutrophil transendothelial migration via up-regulation of interleukin-8 in human brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 277: 10445–10451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107348200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.London C, Mathie T, Stingle N, Clifford C, Haney S, Klein MK, Beaver L, Vickery K, Vail DM, Hershey B, Ettinger S, Vaughan A, Alvarez F, Hillman L, Kiselow M, Thamm D, Higginbotham ML, Gauthier M, Krick E, Phillips B, Ladue T, Jones P, Bryan J, Gill V, Novasad A, Fulton L, Carreras J, McNeill C, Henry C, Gillings S. 2012. Preliminary evidence for biologic activity of toceranib phosphate (Palladia(®)) in solid tumours. Vet Comp Oncol 10: 194–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5829.2011.00275.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.London CA, Hannah AL, Zadovoskaya R, Chien MB, Kollias-Baker C, Rosenberg M, Downing S, Post G, Boucher J, Shenoy N, Mendel DB, McMahon G, Cherrington JM. 2003. Phase I dose-escalating study of SU11654, a small molecule receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in dogs with spontaneous malignancies. Clin Cancer Res 9: 2755–2768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.London CA, Malpas PB, Wood-Follis SL, Boucher JF, Rusk AW, Rosenberg MP, Henry CJ, Mitchener KL, Klein MK, Hintermeister JG, Bergman PJ, Couto GC, Mauldin GN, Michels GM. 2009. Multi-center, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized study of oral toceranib phosphate (SU11654), a receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of dogs with recurrent (either local or distant) mast cell tumor following surgical excision. Clin Cancer Res 15: 3856–3865. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Louvet C, Szot GL, Lang J, Lee MR, Martinier N, Bollag G, Zhu S, Weiss A, Bluestone JA. 2008. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors reverse type 1 diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 18895–18900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810246105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morita S, Villalta SA, Feldman HC, Register AC, Rosenthal W, Hoffmann-Petersen IT, Mehdizadeh M, Ghosh R, Wang L, Colon-Negron K, Meza-Acevedo R, Backes BJ, Maly DJ, Bluestone JA, Papa FR. 2017. Targeting ABL-IRE1α signaling spares ER-stressed pancreatic β cells to reverse autoimmune diabetes. Cell Metab 25: 883–897.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olsson AK, Dimberg A, Kreuger J, Claesson-Welsh L. 2006. VEGF receptor signalling-in control of vascular function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 359–371. doi: 10.1038/nrm1911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paniagua RT, Sharpe O, Ho PP, Chan SM, Chang A, Higgins JP, Tomooka BH, Thomas FM, Song JJ, Goodman SB, Lee DM, Genovese MC, Utz PJ, Steinman L, Robinson WH. 2006. Selective tyrosine kinase inhibition by imatinib mesylate for the treatment of autoimmune arthritis. J Clin Invest 116: 2633–2642. doi: 10.1172/JCI28546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossant J, Howard L. 2002. Signaling pathways in vascular development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 18: 541–573. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.012502.105825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sadanaga A, Nakashima H, Masutani K, Miyake K, Shimizu S, Igawa T, Sugiyama N, Niiro H, Hirakata H, Harada M. 2005. Amelioration of autoimmune nephritis by imatinib in MRL/lpr mice. Arthritis Rheum 52: 3987–3996. doi: 10.1002/art.21424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scaldaferri F, Vetrano S, Sans M, Arena V, Straface G, Stigliano E, Repici A, Sturm A, Malesci A, Panes J, Yla-Herttuala S, Fiocchi C, Danese S. 2009. VEGF-A links angiogenesis and inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 136: 585–95.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez JY, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A. 2012. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9: 676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimokawa C, Kato T, Takeuchi T, Ohshima N, Furuki T, Ohtsu Y, Suzue K, Imai T, Obi S, Olia A, Izumi T, Sakurai M, Arakawa H, Ohno H, Hisaeda H. 2020. CD8+ regulatory T cells are critical in prevention of autoimmune-mediated diabetes. Nat Commun 11: 1922. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15857-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Villalta SA, Lang J, Kubeck S, Kabre B, Szot GL, Calderon B, Wasserfall C, Atkinson MA, Brekken RA, Pullen N, Arch RH, Bluestone JA. 2013. Inhibition of VEGFR-2 reverses type 1 diabetes in NOD mice by abrogating insulitis and restoring islet function. Diabetes 62: 2870–2878. doi: 10.2337/db12-1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson CS, Spaeth JM, Karp J, Stocks BT, Hoopes EM, Stein RW, Moore DJ. 2019. B lymphocytes protect islet β cells in diabetes prone NOD mice treated with imatinib. JCI Insight 5: e125317. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.125317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoo SA, Kwok SK, Kim WU. 2008. Proinflammatory role of vascular endothelial growth factor in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis: prospects for therapeutic intervention. Mediators Inflamm 2008: 129873. doi: 10.1155/2008/129873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]