Abstract

The advent of high-throughput technologies has enabled the analysis of minute amounts of tumor-derived material purified from body fluids, termed liquid biopsies. Prostate cancer (PCa) management, like in many other cancer types, has benefited from liquid biopsies at several stages of the disease. Although initially describing circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in blood, the term “liquid biopsy” has come to more prominently include cell-free, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), RNA, proteins and other molecules. They provide tumor molecular information representing the entire, often-heterogeneous disease, relatively non-invasively and longitudinally. Blood has been the main liquid biopsy specimen in PCa, and urine has also proven beneficial. Technological advances have allowed clinical implementation of some liquid biopsies in prostate cancer, in disease monitoring and precision oncology. This narrative review introduces the main types of blood-based PCa liquid biopsies focusing on advances in the past 5 years. Clinical adoption of liquid biopsies to detect and monitor the evolving PCa tumor biology promise to deepen our understanding of the disease and improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: prostate cancer, liquid biopsy, ctDNA, CTC, extracellular vesicles

1. Introduction

Although the term liquid biopsy was initially coined over a decade ago to refer to circulating tumor cells (CTCs, intact cancer cells disseminated from tumors and found in blood) by Pantel and Alix-Panabieres1, detection of blood-derived tumor material had existed much longer with the measurement of several protein-based biomarkers, most prominently the prostate specific antigen (PSA) in prostate cancer (PCa)2. Technological advances over the past two decades, notably in next generation sequencing (NGS) of nucleic acids extracted from tissue has led to a better understanding of PCa driver genomic alterations 3,4. This has allowed extension of this knowledge to liquid biopsies by developments in interrogation of the small amounts of nucleic acids, proteins and other analytes obtained from body fluids, such as blood and urine. Prominent among these is detection of cell-free, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), thought to be released by dying (or live) cancer cells. Detection of somatic ctDNA mutations in plasma and their fraction as a component of the total (mutant and normal) DNA reflects disease burden and portends worse prognosis at various stages5,6. Likewise, the number of CTCs in blood of PCa patients is also associated with disease burden and prognosis7. Further, liquid biopsy tends to be minimally invasive, thus allowing serial monitoring, which is key given the propensity of tumors to evolve in response to endogenous constraints and selective therapeutic pressures8. Rapid turnover of cancer-derived materials in blood (measured in hours for CTC and ctDNA) means a near real-time picture of the evolving disease. Liquid biopsy is also thought to contain a broader representation of the entire disease compared to localized tissue biopsies. This is important given the heterogenous nature of most cancers9,10, but it is especially central in PCa given the propensity for multifocal disease11. This narrative review introduces the main areas of application of blood-based liquid biopsy in PCa with the goal of describing advances made in the past 5 years.

2. Methods

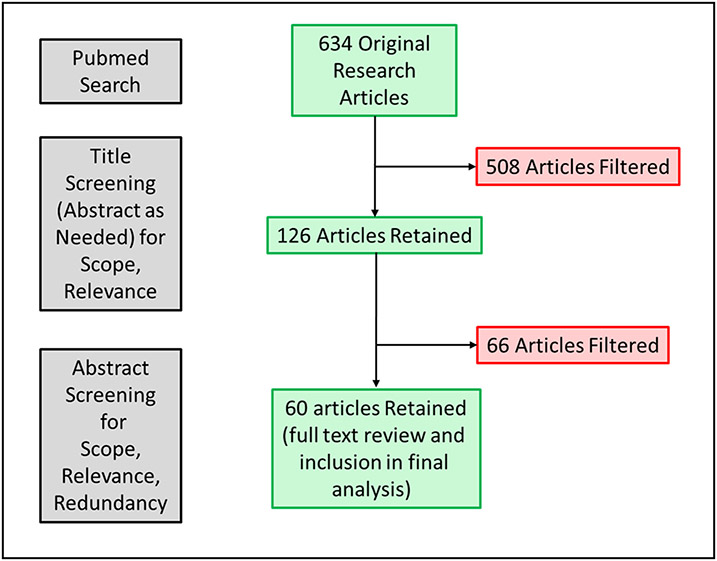

A literature search was performed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) criteria. The topics for this semi-systematic PCa liquid biopsy review were pre-defined: CTCs, ctDNA, and extracellular vesicles. A search of PUBMED database using the following terms: “prostate cancer” AND (CTC OR ctDNA OR “extracellular vesicles” OR “liquid biopsy”) was performed. Studies were excluded due to inability to access the full article, non-English manuscripts, and those belonging to excluded publication types i.e., not presenting original research and studies not involving male human subjects/samples. The search was limited to publications in the past 5 years since the time of manuscript preparation (03/2018 – 03/2023). A total of 634 articles were initially identified followed by unbiased screening according to the above pre-established criteria. Articles on malignancies other than PCa or those not solely focused on PCa, or non-relevant to the scope/topics of the review, were filtered out based on title (and abstract, as needed) review. This yielded 126 articles for which abstract evaluation was performed for relevance with the scope/topics of the review or redundancy with others. Publications with the highest level of evidence were selected for review. This yielded 60 articles for which full text evaluation was performed and included in the final review12-71. A flow diagram of the articles’ evaluation process is shown in Figure 1. Both authors reviewed and approved the search/filtering strategy and the final reference list. The results of the literature search are grouped by topic and presented in a narrative fashion.

Figure 1.

Flow chart detailing literature search and selection of articles.

3. Evidence synthesis

ctDNA

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has provided biological insights in multiple cancer types, including PCa72. Methods used for detection have included the highly sensitive droplet digital PCR (ddPCR); NGS, which can take the form of deep targeted sequencing (fixed gene panel or tailor-made, bespoke panels based on a patient’s cancer tissue mutations), as well as low-pass whole genome sequencing; and methylomic/fragmentomic analysis to infer gene expression, amongst others.

Notable advances have been made in solidifying methodology, consolidating the value of ctDNA fraction in circulation as a marker of poor prognosis, studying ctDNA behavior under various treatment regimens, etc. Thus, a comparison of a major commercial ctDNA sequencing assay (Guardant360) with an academic laboratory-based gene panel identified very good concordance at 1% ctDNA fraction or above, below which, alteration calls became considerably discordant/questionable27. When correlated to serum PSA, 4 of every 5 PCa patients with a PSA of >5 ng/ml were above the 1% ctDNA tumor fraction threshold, as opposed to fewer than half of patients with a PSA <5ng/ul26. Comparison of ctDNA findings to those in matched, synchronous tissue biopsies as the benchmark method has continued to be studied. In a de-novo metastatic, castration-sensitive cohort, ctDNA was 80% concordant with tissue in detecting genomic alterations, indicating complementarity between the two approaches21. A larger cohort of mCRPC patients reflected this high tissue-ctDNA concordance, including in the actionable BRCA1/2 gene alterations, but less so in putative resistance alterations found in ctDNA17. The reasons for the observed high, but imperfect concordance, also seen in other cancer types, can be varied. They likely include time between the tissue and liquid biopsies (reflecting tumor evolution, especially in late, heavily treated disease12,25,73), intra-patient heterogeneity more likely to be fully captured in ctDNA than in tissue14,25, and a deeper analysis of the specific region of the lesion biopsied in tissue due to higher tumor fraction vs. broader, lower tumor fraction analysis in ctDNA.

The independent prognostic impact of ctDNA fraction in PCa patients undergoing various therapies has been demonstrated in several studies. In mCRPC patients on taxane chemotherapy, a higher baseline circulating total cell-free DNA content in blood (not ctDNA, but total DNA, including that of normal origin) as well as a cell-free DNA response (decrease upon treatment initiation), was associated with a shorter progression-free and overall survival6. This is important as it avoids the need for DNA sequencing. A look at the actual tumor-derived ctDNA in the same cohort by low-pass (i.e., shallow) whole genome sequencing, equally found prognostic association of ctDNA content with progression-free and overall survival22. Similar findings were obtained in enzalutamide or abiraterone-treated mCRPC patients20, whereas the role of ctDNA in predicting success of abiraterone-to-enzalutamide treatment switch was not straightforward and depended on the genomic alterations13. Apalutamide added to ADT in the non-metastatic setting did not cause any marked changes in ctDNA alterations in blood16. Meanwhile, looking at circulating RNAs, Benoist and colleagues identified microRNA miR-3687 and confirmed miR-375 as poor prognosis factors for mCRPC patients being treated with enzalutamide18.

Lineage plasticity, known to be involved in trans-differentiation of treatment-resistant mCRPC into truly androgen independent neuroendocrine cancer was detected in ctDNA by Beltran et al. using whole exome DNA and bisulfite sequencing (to detect DNA methylation patterns). High detection accuracy was obtained by combining genetic (RB1, TP53) and epigenetic (ASXL3, SPDEF) alterations23. Hypermethylated ctDNA of DOCK2, HAPLN3, and FBXO30 was a poor prognostic factor for development of mCRPC from localized or non-existing PCa15, whereas global ctDNA hypermethylation (with hypomethylation of regions near centromeres) distinguished metastatic PCa from localized disease24. Finally, Nimir and colleagues tackled a comparison of detecting AR-V7 (an AR splice variant associated with advanced anti-androgen therapy resistance; see CTC section below) in circulating RNA, CTCs and extracellular vesicles, showing a significant advantage of CTCs in detecting AR-V7, also aided by the frequent presence of CTCs in advanced mCRPC disease29.

CTCs

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) provide useful prognostic and predictive information in PCa. Generally, half, or more patients have detectable cancer cells in their blood, depending on disease stage, method of detection and other factors74. PCa CTC detection by the FDA-cleared CellSearch® method based on EpCAM immunomagnetic enrichment was established early7. Other approaches, such as apheresis-based methods that screen larger volumes of blood to retrieve CTCs and route the rest of blood components back into circulation have shown the ability to isolate greater numbers of CTCs75. This has been followed by the demonstration in PCa of the prognostic value of CTC counts7,31,37 in line with several other cancer types where presence of greater numbers of CTCs, unsurprisingly, portends poorer prognosis76. Demonstration of several other CTC detection/isolation platforms in PCa have since followed, some in the recent past. Most notably, the EPIC® system uses an enrichment-free platform where nucleated cells are smeared on glass slides and analyzed using digital pathology based on morphological and other factors. Using this method, CTC enumeration was shown to be highly-concordant to CellSearch® (r=0.84) and prognostic of overall survival in advanced PCa patients35. With the same platform, Salami et al. found CTCs in 73% of high-risk localized PCa patient, being often heterogeneous in their expression of epithelial cytokeratin markers and androgen receptor (AR), consistent with epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)46. Single-cell whole genome sequencing allowed copy number profiling revealing further, genomic heterogeneity. Greater CTC counts, AR+ CTCs, and phenotypic heterogeneity by this method correlated with biochemical recurrence and development of metastatic disease on imaging46.

Advances in methods to isolate and characterize CTC have provided opportunities for their utilization not only to gain biological insights, but in some cases yield biomarkers with proven clinical utility, such as markers of anti-androgen therapy resistance and predictive of chemotherapy benefit. Advanced PCa patients whose cancer develops resistance to the initial androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), so-called metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), commonly benefit from next generation AR signaling blockers (e.g., abiraterone, enzalutamide and apalutamide). Persistent AR blockade, however, drives the development of a constitutively active, truncated AR splice variant, AR-V7, which lacks the androgen ligand binding domain, the direct/indirect target of those inhibitors. CTCs have become an optimal analyte for non-invasive AR-V7 detection. Thus, CTC AR-V7 has been shown to be a biomarker of resistance to next generation AR blockade in mCRPC50,77, and of benefit from taxane chemotherapy instead78. A more recent report, however, finds unclear evidence for CTC AR-V7 positivity as providing additional, statistically significant prognostic value beyond known prognosticators such as CTC enumeration47. In another study, this was especially true in patients with high CTC counts42. This latter study’s population consisted mostly of patients already undergoing taxane treatment (sometimes chosen based on AR-V7 positivity), thus it may define a strata of patients where this biomarker’s value is confounded/not present42. The former study was also comprised of a population receiving heterogeneous treatment types47. A third study, by Sieuwerts et al. did not find association of AR-V7 with outcome on cabazitaxel, a taxane chemotherapy45. Indeed, at present, the clinical utility of AR-V7 detected on CTCs seems to be greatest in selecting patients for AR signaling inhibitor vs. taxane chemotherapy in mCRPC 41, although one report demonstrated prognostic ability of AR-V7 (and its related variant, ARv567es) in taxane treatment48.

Work toward identification of expression of other variants/genes in early ADT treatment33,34, and beyond AR-V7 in advanced disease as prognostic factors in PCa CTCs continues. For example, the presence of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-positive CTCs in CRPC portended a shorter biochemical recurrence-free survival in patients progressing on one line of therapy and starting the next40. This is also exemplified by Cheung et al. who looked at a panel of 89 transcripts identifying an 8-gene signature including AR-V7, that outperformed AR-V7 alone in predicting biochemical recurrence44.

CTC profiling has made headways in other PCa biomarker areas such as detection of deletions in homologous recombination DNA damage repair genes, approved markers of benefit from PARP inhibition in mCRPC, another area of excitement in PCa therapy (and in other cancer types). Thus, Barnett and colleagues were able to detect BRCA2 loss at the single-cell level in CTCs of mCRPC patients equally accurately as in matched non-osseous tissue biopsies and more accurately than in bone biopsies32. Similarly, work by the same group measured single-cell, genome-wide chromosomal instability (largely an outcome of deficient homologous recombination repair) by DNA sequencing39. This instability was correlated with, and could be recapitulated by cell morphological changes that, when analyzed with digital pathology methods, yielded a model that could prognosticate outcomes on AR-directed or taxane therapy.

As a result of persistent AR-inhibition, formerly AR-dependent PCa undergoes lineage plasticity and trans-differentiates into neuroendocrine (NE) PCa. Zhao at al. recently reported on detection by RT-qPCR of the expression of NE markers synaptophysin (SYN) and chromogranin-A (CHGA) together with AR signaling reporter transcripts in CTCs. They showed 100% accuracy of detecting NE disease at the patient level against known, tissue-based NE status in at least one blood sample over longitudinal monitoring30. Indeed interest in the serial tracing of patients by CTC liquid biopsy to monitor prognosis and response to therapies, tumor heterogeneity and evolution, and other applications has been growing recently in several cancer types as in PCa36,43,49,79,80. Lorente et al. found that an increase in CTC counts compared to baseline in advanced PCa patients starting AR-directed treatment or chemotherapy was associated with worse overall survival49. A report by Hille and colleagues devised a method to detect AR-V7 in PCa from CTCs enriched by the FDA-cleared CellSearch® system, which could be useful for clinical monitoring of AR-directed therapy43. Likewise, Gupta et al. analyzed CTC samples from mCRPC patients at the start of, and after progression on next generation AR inhibitors to detect mutations and copy number alterations revealing CTC genomic heterogeneity and evolution, at times in genes related to NE differentiation such as RB1 and TP5336. CTC platelet cloaking (the covering of the CTC surface by platelets speculated to protect CTCs in transit in the bloodstream from harsh conditions, the immune system etc.81) is also beginning to be studied in PCa38,82. Ongoing strategies include comparing/combining CTCs with circulating DNA/RNA and/or extracellular vesicles 28,29.

Extracellular Vesicles

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), or exosomes, are nano-scale, membrane-enclosed cellular fragments released into the extracellular environment carrying RNA, DNA, protein and other cell components. They are speculated to have intriguing functions in cancer, from preparing the distant metastatic niche to transforming normal cells. Recent work in EVs of PCa patients has complemented earlier studies by shedding light on several aspects such as methodology, individual biomarkers, and panel-based studies of multiple markers contained in them in diagnosis and risk stratification of early disease or at prostatectomy, using both urine and blood-based approaches. In a small cohort, Pang et al. showed that size-exclusion chromatography-based methods provided purer populations of EVs compared to precipitation methods in blood for PCa diagnosis70. Notably, the ExoDx Prostate (IntelliScore) test based on EV detection of long non-coding and gene fusion RNAs in urine has been shown to aid detection of high-risk disease 66 67. Likewise, when performed prior to repeat biopsies in men with previous negative biopsies, the ExoDx test could predict high risk disease in the repeat biopsy setting64. In other assays, plasma EVs positive for the protein STEAP1 had significant biomarker potential for detection/diagnosis but carried little prognostic information69. Urine EV RNA profiling assayed by ddPCR identified the long non-coding RNAs PCA3 (an established urine PCa biomarker) and PCGEM1 as predictors of high-grade cancer on diagnostic biopsy65. And as mentioned above, EVs demonstrated inferior performance characteristics when compared to CTCs in AR-V7 detection29. Other urine-based approaches that may include EV-derived materials have been reported51-63. Lastly, proteomic EV profiling in sera of PCa patients has shown some prognostic potential68.

4. Limitations

We did not perform a comprehensive systematic review and confined the review to publications on the topics of ctDNA, CTCs and EVs in the last 5 years. The search terms used may not be exhaustive and filtering criteria based on redundancy of topic/findings between publications may have removed secondary or supplemental findings not included in the retained papers. Except for the topic of EVs, urine based PCa liquid biopsy is largely not covered in this review. Nevertheless, our review captured the key advancements in the field of PCa liquid biopsy research over the last 5 years.

5. Conclusions

In this review, we describe recent advances and clinical applications of blood-based liquid biopsy approaches in prostate cancer including ctDNA, CTCs, and EVs. The current data demonstrates the prognostic and, in some cases, the predictive capacity of liquid biopsy. Importantly, optimization of the technology and techniques for acquiring and analyzing liquid biopsy specimens will better our understanding of the biology of the disease across the of prostate cancer clinical continuum as well facilitate integration into patient care paradigms.

Financial Support:

S.S.S. is supported by the Prostate Cancer Foundation, the National Institutes of Health (the University of Michigan Prostate S.P.O.R.E., P50 CA186786-05), the Men of Michigan Prostate Cancer Research Fund, the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center core grant (2-P30-CA-046592-24), the A. Alfred Taubman Biomedical Research Institute, the Department of Defense, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation as part of the Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program (AMFDP), and the Urology Care Foundation Rising Stars in Urology Research Award Program and Astellas, Inc.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of U-M Precision Health. S.S.S. is on a study advisory committee for Bayer Pharma and has a non-sponsored research agreement with GenomeDx. A.K.C. has no conflict of interest to disclose.

References:

- 1.Pantel K, Alix-Panabieres C: Circulating tumour cells in cancer patients: challenges and perspectives. Trends Mol Med 16:398–406, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stamey TA, Yang N, Hay AR, et al. : Prostate-specific antigen as a serum marker for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. N Engl J Med 317:909–16, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N: The Molecular Taxonomy of Primary Prostate Cancer. Cell 163:1011–25, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bostrom PJ, Bjartell AS, Catto JW, et al. : Genomic Predictors of Outcome in Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol 68:1033–44, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choudhury AD, Werner L, Francini E, et al. : Tumor fraction in cell-free DNA as a biomarker in prostate cancer. JCI Insight 3, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehra N, Dolling D, Sumanasuriya S, et al. : Plasma Cell-free DNA Concentration and Outcomes from Taxane Therapy in Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer from Two Phase III Trials (FIRSTANA and PROSELICA). Eur Urol 74:283–291, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Bono JS, Scher HI, Montgomery RB, et al. : Circulating tumor cells predict survival benefit from treatment in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 14:6302–9, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbosh C, Frankell AM, Harrison T, et al. : Tracking early lung cancer metastatic dissemination in TRACERx using ctDNA. Nature 616:553–562, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144:646–74, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, et al. : Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med 366:883–892, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boutros PC, Fraser M, Harding NJ, et al. : Spatial genomic heterogeneity within localized, multifocal prostate cancer. Nat Genet 47:736–45, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn AW, Stenehjem D, Nussenzveig R, et al. : Evolution of the genomic landscape of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in metastatic prostate cancer over treatment and time. Cancer Treat Res Commun 19:100120, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moses M, Niu A, Lilly MB, et al. : Circulating-tumor DNA as predictor of enzalutamide response post-abiraterone treatment in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Treat Res Commun 24:100193, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Necchi A, Cucchiara V, Grivas P, et al. : Contrasting genomic profiles from metastatic sites, primary tumors, and liquid biopsies of advanced prostate cancer. Cancer 127:4557–4564, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjerre MT, Norgaard M, Larsen OH, et al. : Epigenetic Analysis of Circulating Tumor DNA in Localized and Metastatic Prostate Cancer: Evaluation of Clinical Biomarker Potential. Cells 9, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith MR, Thomas S, Gormley M, et al. : Blood Biomarker Landscape in Patients with High-risk Nonmetastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Treated with Apalutamide and Androgen-Deprivation Therapy as They Progress to Metastatic Disease. Clin Cancer Res 27:4539–4548, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tukachinsky H, Madison RW, Chung JH, et al. : Genomic Analysis of Circulating Tumor DNA in 3,334 Patients with Advanced Prostate Cancer Identifies Targetable BRCA Alterations and AR Resistance Mechanisms. Clin Cancer Res 27:3094–3105, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benoist GE, van Oort IM, Boerrigter E, et al. : Prognostic Value of Novel Liquid Biomarkers in Patients with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Treated with Enzalutamide: A Prospective Observational Study. Clin Chem 66:842–851, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peter MR, Bilenky M, Shi Y, et al. : A novel methylated cell-free DNA marker panel to monitor treatment response in metastatic prostate cancer. Epigenomics 14:811–822, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fettke H, Kwan EM, Bukczynska P, et al. : Prognostic Impact of Total Plasma Cell-free DNA Concentration in Androgen Receptor Pathway Inhibitor-treated Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol Focus 7:1287–1291, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vandekerkhove G, Struss WJ, Annala M, et al. : Circulating Tumor DNA Abundance and Potential Utility in De Novo Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol 75:667–675, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sumanasuriya S, Seed G, Parr H, et al. : Elucidating Prostate Cancer Behaviour During Treatment via Low-pass Whole-genome Sequencing of Circulating Tumour DNA. Eur Urol 80:243–253, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beltran H, Romanel A, Conteduca V, et al. : Circulating tumor DNA profile recognizes transformation to castration-resistant neuroendocrine prostate cancer. J Clin Invest 130:1653–1668, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen S, Petricca J, Ye W, et al. : The cell-free DNA methylome captures distinctions between localized and metastatic prostate tumors. Nat Commun 13:6467, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herberts C, Annala M, Sipola J, et al. : Deep whole-genome ctDNA chronology of treatment-resistant prostate cancer. Nature 608:199–208, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Antonarakis ES, Tierno M, Fisher V, et al. : Clinical and pathological features associated with circulating tumor DNA content in real-world patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Prostate 82:867–875, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taavitsainen S, Annala M, Ledet E, et al. : Evaluation of Commercial Circulating Tumor DNA Test in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol 3, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kohli M, Li J, Du M, et al. : Prognostic association of plasma cell-free DNA-based androgen receptor amplification and circulating tumor cells in pre-chemotherapy metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 21:411–418, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nimir M, Ma Y, Jeffreys SA, et al. : Detection of AR-V7 in Liquid Biopsies of Castrate Resistant Prostate Cancer Patients: A Comparison of AR-V7 Analysis in Circulating Tumor Cells, Circulating Tumor RNA and Exosomes. Cells 8, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao SG, Sperger JM, Schehr JL, et al. : A clinical-grade liquid biomarker detects neuroendocrine differentiation in prostate cancer. J Clin Invest 132, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swami U, Sayegh N, Jo Y, et al. : External Validation of Association of Baseline Circulating Tumor Cell Counts with Survival Outcomes in Men with Metastatic Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 21:1857–1861, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barnett ES, Schultz N, Stopsack KH, et al. : Analysis of BRCA2 Copy Number Loss and Genomic Instability in Circulating Tumor Cells from Patients with Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol 83:112–120, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zavridou M, Smilkou S, Tserpeli V, et al. : Development and Analytical Validation of a 6-Plex Reverse Transcription Droplet Digital PCR Assay for the Absolute Quantification of Prostate Cancer Biomarkers in Circulating Tumor Cells of Patients with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin Chem 68:1323–1335, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reichert ZR, Kasputis T, Nallandhighal S, et al. : Multigene Profiling of Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) for Prognostic Assessment in Treatment-Naive Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer (mHSPC). Int J Mol Sci 23, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scher HI, Armstrong AJ, Schonhoft JD, et al. : Development and validation of circulating tumour cell enumeration (Epic Sciences) as a prognostic biomarker in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer 150:83–94, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta S, Halabi S, Kemeny G, et al. : Circulating Tumor Cell Genomic Evolution and Hormone Therapy Outcomes in Men with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Mol Cancer Res 19:1040–1050, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldkorn A, Tangen C, Plets M, et al. : Baseline Circulating Tumor Cell Count as a Prognostic Marker of PSA Response and Disease Progression in Metastatic Castrate-Sensitive Prostate Cancer (SWOG S1216). Clin Cancer Res 27:1967–1973, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brady L, Hayes B, Sheill G, et al. : Platelet cloaking of circulating tumour cells in patients with metastatic prostate cancer: Results from ExPeCT, a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 15:e0243928, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schonhoft JD, Zhao JL, Jendrisak A, et al. : Morphology-Predicted Large-Scale Transition Number in Circulating Tumor Cells Identifies a Chromosomal Instability Biomarker Associated with Poor Outcome in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res 80:4892–4903, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagaya N, Nagata M, Lu Y, et al. : Prostate-specific membrane antigen in circulating tumor cells is a new poor prognostic marker for castration-resistant prostate cancer. PLoS One 15:e0226219, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Graf RP, Hullings M, Barnett ES, et al. : Clinical Utility of the Nuclear-localized AR-V7 Biomarker in Circulating Tumor Cells in Improving Physician Treatment Choice in Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol 77:170–177, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belderbos BPS, Sieuwerts AM, Hoop EO, et al. : Associations between AR-V7 status in circulating tumour cells, circulating tumour cell count and survival in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer 121:48–54, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hille C, Gorges TM, Riethdorf S, et al. : Detection of Androgen Receptor Variant 7 (ARV7) mRNA Levels in EpCAM-Enriched CTC Fractions for Monitoring Response to Androgen Targeting Therapies in Prostate Cancer. Cells 8, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung JS, Wang Y, Henderson J, et al. : Circulating Tumor Cell-Based Molecular Classifier for Predicting Resistance to Abiraterone and Enzalutamide in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Neoplasia 21:802–809, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sieuwerts AM, Onstenk W, Kraan J, et al. : AR splice variants in circulating tumor cells of patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer: relation with outcome to cabazitaxel. Mol Oncol 13:1795–1807, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salami SS, Singhal U, Spratt DE, et al. : Circulating Tumor Cells as a Predictor of Treatment Response in Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol 3, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharp A, Welti JC, Lambros MBK, et al. : Clinical Utility of Circulating Tumour Cell Androgen Receptor Splice Variant-7 Status in Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol 76:676–685, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tagawa ST, Antonarakis ES, Gjyrezi A, et al. : Expression of AR-V7 and ARv(567es) in Circulating Tumor Cells Correlates with Outcomes to Taxane Therapy in Men with Metastatic Prostate Cancer Treated in TAXYNERGY. Clin Cancer Res 25:1880–1888, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lorente D, Olmos D, Mateo J, et al. : Circulating tumour cell increase as a biomarker of disease progression in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients with low baseline CTC counts. Ann Oncol 29:1554–1560, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Wang H, et al. : AR-V7 and resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 371:1028–38, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson H, Guo J, Zhang X, et al. : Development and validation of a 25-Gene Panel urine test for prostate cancer diagnosis and potential treatment follow-up. BMC Med 18:376, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cani AK, Hu K, Liu CJ, et al. : Development of a Whole-urine, Multiplexed, Next-generation RNA-sequencing Assay for Early Detection of Aggressive Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol Oncol 5:430–439, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jeon J, Olkhov-Mitsel E, Xie H, et al. : Temporal Stability and Prognostic Biomarker Potential of the Prostate Cancer Urine miRNA Transcriptome. J Natl Cancer Inst 112:247–255, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Larsen LK, Jakobsen JS, Abdul-Al A, et al. : Noninvasive Detection of High Grade Prostate Cancer by DNA Methylation Analysis of Urine Cells Captured by Microfiltration. J Urol 200:749–757, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eskra JN, Rabizadeh D, Zhang J, et al. : Specific Detection of Prostate Cancer Cells in Urine by RNA In Situ Hybridization. J Urol 206:37–43, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tosoian JJ, Trock BJ, Morgan TM, et al. : Use of the MyProstateScore Test to Rule Out Clinically Significant Cancer: Validation of a Straightforward Clinical Testing Approach. J Urol 205:732–739, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Newcomb LF, Zheng Y, Faino AV, et al. : Performance of PCA3 and TMPRSS2:ERG urinary biomarkers in prediction of biopsy outcome in the Canary Prostate Active Surveillance Study (PASS). Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 22:438–445, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tutrone R, Donovan MJ, Torkler P, et al. : Clinical utility of the exosome based ExoDx Prostate(IntelliScore) EPI test in men presenting for initial Biopsy with a PSA 2-10 ng/mL. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 23:607–614, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hendriks RJ, van der Leest MMG, Israel B, et al. : Clinical use of the SelectMDx urinary-biomarker test with or without mpMRI in prostate cancer diagnosis: a prospective, multicenter study in biopsy-naive men. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 24:1110–1119, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Margolis E, Brown G, Partin A, et al. : Predicting high-grade prostate cancer at initial biopsy: clinical performance of the ExoDx (EPI) Prostate Intelliscore test in three independent prospective studies. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 25:296–301, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao F, Vesprini D, Liu RSC, et al. : Combining urinary DNA methylation and cell-free microRNA biomarkers for improved monitoring of prostate cancer patients on active surveillance. Urol Oncol 37:297 e9–297 e17, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eyrich NW, Wei JT, Niknafs YS, et al. : Association of MyProstateScore (MPS) with prostate cancer grade in the radical prostatectomy specimen. Urol Oncol 40:4 e1–4 e7, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lebastchi AH, Russell CM, Niknafs YS, et al. : Impact of the MyProstateScore (MPS) Test on the Clinical Decision to Undergo Prostate Biopsy: Results From a Contemporary Academic Practice. Urology 145:204–210, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McKiernan J, Noerholm M, Tadigotla V, et al. : A urine-based Exosomal gene expression test stratifies risk of high-grade prostate Cancer in men with prior negative prostate biopsy undergoing repeat biopsy. BMC Urol 20:138, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kohaar I, Chen Y, Banerjee S, et al. : A Urine Exosome Gene Expression Panel Distinguishes between Indolent and Aggressive Prostate Cancers at Biopsy. J Urol 205:420–425, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kretschmer A, Kajau H, Margolis E, et al. : Validation of a CE-IVD, urine exosomal RNA expression assay for risk assessment of prostate cancer prior to biopsy. Sci Rep 12:4777, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kretschmer A, Tutrone R, Alter J, et al. : Pre-diagnosis urine exosomal RNA (ExoDx EPI score) is associated with post-prostatectomy pathology outcome. World J Urol 40:983–989, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Signore M, Alfonsi R, Federici G, et al. : Diagnostic and prognostic potential of the proteomic profiling of serum-derived extracellular vesicles in prostate cancer. Cell Death Dis 12:636, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Khanna K, Salmond N, Lynn KS, et al. : Clinical significance of STEAP1 extracellular vesicles in prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 24:802–811, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pang B, Zhu Y, Ni J, et al. : Quality Assessment and Comparison of Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Separated by Three Commercial Kits for Prostate Cancer Diagnosis. Int J Nanomedicine 15:10241–10256, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chi KN, Barnicle A, Sibilla C, et al. : Detection of BRCA1, BRCA2, and ATM Alterations in Matched Tumor Tissue and Circulating Tumor DNA in Patients with Prostate Cancer Screened in PROfound. Clin Cancer Res 29:81–91, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, et al. : Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med 6:224ra24, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu MC, MacKay M, Kase M, et al. : Longitudinal Shifts of Solid Tumor and Liquid Biopsy Sequencing Concordance in Metastatic Breast Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol 6:e2100321, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Morgan TM, Lange PH, Porter MP, et al. : Disseminated tumor cells in prostate cancer patients after radical prostatectomy and without evidence of disease predicts biochemical recurrence. Clin Cancer Res 15:677–83, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lambros MB, Seed G, Sumanasuriya S, et al. : Single-Cell Analyses of Prostate Cancer Liquid Biopsies Acquired by Apheresis. Clin Cancer Res 24:5635–5644, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, et al. : Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 351:781–91, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Armstrong AJ, Halabi S, Luo J, et al. : Prospective Multicenter Validation of Androgen Receptor Splice Variant 7 and Hormone Therapy Resistance in High-Risk Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: The PROPHECY Study. J Clin Oncol 37:1120–1129, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Scher HI, Graf RP, Schreiber NA, et al. : Phenotypic Heterogeneity of Circulating Tumor Cells Informs Clinical Decisions between AR Signaling Inhibitors and Taxanes in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res 77:5687–5698, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Paoletti C, Cani AK, Larios JM, et al. : Comprehensive Mutation and Copy Number Profiling in Archived Circulating Breast Cancer Tumor Cells Documents Heterogeneous Resistance Mechanisms. Cancer Res 78:1110–1122, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cani AK, Dolce EM, Darga EP, et al. : Serial monitoring of genomic alterations in circulating tumor cells of ER-positive/HER2-negative advanced breast cancer: feasibility of precision oncology biomarker detection. Mol Oncol 16:1969–1985, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Darga EP, Dolce EM, Fang F, et al. : PD-L1 expression on circulating tumor cells and platelets in patients with metastatic breast cancer. PLoS One 16:e0260124, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chai S, Matsumoto N, Storgard R, et al. : Platelet-Coated Circulating Tumor Cells Are a Predictive Biomarker in Patients with Metastatic Castrate-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Mol Cancer Res 19:2036–2045, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]