Abstract

Considering the undesirable metabolic stability of our recently identified NNRTI 5 (t1/2 = 96 min) in human liver microsomes, we directed our efforts to improve its metabolic stability by introducing a new favorable hydroxymethyl side chain to the C-5 position of pyrimidine. This strategy provided a series of novel methylol-biphenyl-diarylpyrimidines with excellent anti-HIV-1 activity. The best compound 9g was endowed with remarkably improved metabolic stability in human liver microsomes (t1/2 = 2754 min), which was about 29-fold longer than that of 5 (t1/2 = 96 min). This compound conferred picomolar inhibition of WT HIV-1 (EC50 = 0.9 nmol/L) and low nanomolar activity against five clinically drug-resistant mutant strains. It maintained particularly low cytotoxicity (CC50 = 264 μmol/L) and good selectivity (SI = 256,438). Molecular docking studies revealed that compound 9g exhibited a more stable conformation than 5 due to the newly constructed hydrogen bond of the hydroxymethyl group with E138. Also, compound 9g was characterized by good safety profiles. It displayed no apparent inhibition of CYP enzymes and hERG. The acute toxicity assay did not cause death and pathological damage in mice at a single dose of 2 g/kg. These findings paved the way for the discovery and development of new-generation anti-HIV-1 drugs.

Key words: NNRTI, HIV-1, DAPYs, Picomolar, Metabolic stability

Graphical abstract

Herein, we reported the discovery of a picomolar NNRTI 9g featuring significantly improved metabolic stability by introducing a favorable hydroxymethyl side chain to the C-5 position of pyrimidine of 5.

1. Introduction

According to report from the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), more than 38 million people were diagnosed with HIV worldwide in 2021, and approximately 650,000 AIDS-related patients died of HIV1. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is considered the most effective strategy for HIV therapy2, 3, 4, 5, 6. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) have been recognized as a significant component of ART that is widely utilized in combination with other agents for HIV therapy7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12. Diarylpyrimidine (DAPY) derivatives possessed noticeable anti-HIV potency and pharmacological profiles, represented by etravirine (ETR, 1) and rilpivirine (RPV, 2) (Fig. 1)13. However, both of them suffer from poor water solubility, high cytotoxicity, and rapid emergence of drug resistance, which stimulates the demand of searching for novel DAPYs with good security and drug-like properties.

Figure 1.

Structures of representative DAPYs.

Over the past, structural optimization of ETR and RPV has been extensively conducted14, 15, 16, and several series of biphenyl-DAPYs with significant inhibition of wild-type (WT) HIV-1 and mutant viruses were disclosed (Fig. 1). Among these DAPY analogs, compound 3 exhibited extremely high activity against WT HIV-1 (EC50 = 1 nmol/L) and low single-digit nanomolar activity toward various drug-resistant mutants. However, it was highly cytotoxic (CC50 = 2.08 μmol/L) with undesirable metabolic stability in human liver microsomes (t1/2 = 14.6 min)17,18. Then, the substitution of the cyanophenyl group with a heteroaromatic pyridine ring afforded compound 4, whose metabolic stability could not be accurately assessed19. Furthermore, the entrance channel of RT enzyme was also explored by the installation of different groups at different positions of the central pyrimidine core. Notably, compound 5 featuring a methyl tail at the C5-position of pyrimidine was characterized by significantly enhanced metabolic stability in human liver microsome (t1/2 = 1.6 h), which remained an unsatisfactory parameter as a drug candidate20,21.

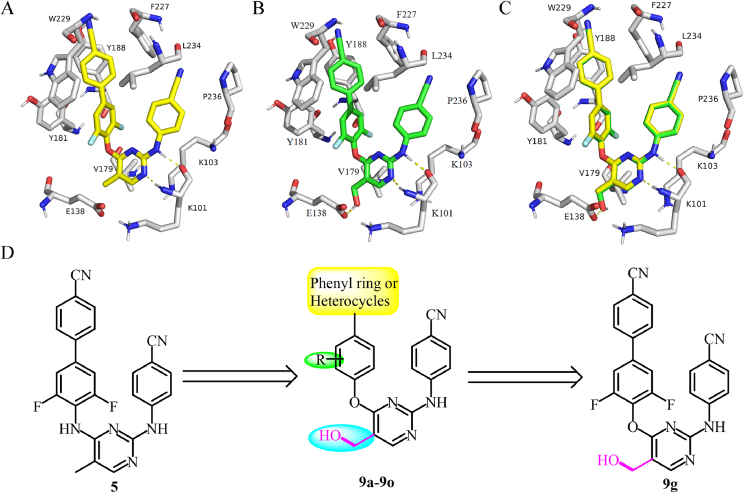

The present investigation work was continually initiated by introducing a new favorable hydroxymethyl side chain to the C-5 position of the pyrimidine of 5, which was expected to enhance its potency and metabolic stability. The molecular docking results indicated that 9g adopted a horseshoe-like configuration, similar to that of 5, as shown in Fig. 2. Compound 9g exhibited a more stable conformation within the allosteric binding pocket of WT RT due to the newly constructed hydrogen bond of the hydroxymethyl group with E138, whereas no similar interaction was observed between 5 and the protein, which was also confirmed by their docking scores (13.173 vs 13.630). To confirm our hypothesis, a novel series of methylol-biphenyl-diarylpyrimidines were synthesized. The early screening assay indicated that all of them (9a‒9o) were endowed with excellent anti-HIV-1 potency. Especially, 9g was characterized by picomolar inhibition of WT HIV-1 (EC50 = 0.9 nmol/L) and low nanomolar inhibition of five drug-resistant mutant strains. Also, 9g exhibited particularly low cytotoxicity and good selectivity (CC50 = 264 μmol/L, SI = 256,438).

Figure 2.

The simulated binding modes of 5 (A) and 9g (B) with WT HIV-1 RT (PDB code: 2ZD1); (C) Overlay of 5 and 9g within the binding pocket; (D) Design of methylol-biphenyl-DAPYs.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

The synthetic method of 9a–9o was depicted in Scheme 1. The nucleophilic substitution of 6, prepared through a well-established protocol22, and appropriate 4-bromophenol was conducted in DMF at 80 °C for 8 h, producing diarylpyrimidines 7a–7g in 76%–92% yields. The intermediates 7a–7g were then subjected to Suzuki-Miyaura coupling, catalyzed by Pd(dppf)Cl2 at 110 °C for 18 h, to give rise to biphenyl-diarylpyrimidines 8a–8o in 55%–78% yields23,24. The desired compounds 9a–9o in 45%–70% yields were finally achieved by the reduction of compounds 8a–8o using DIBAL-H as the catalysis in anhydrous THF at ‒45–0 °C for 12 h.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compounds 9a–9o. Reagents and conditions: (a) substituted 4-bromophenol, Cs2CO3, DMF, 80 °C, 8 h, 76%–92%; (b) arylboromic acid, Pd(dppf)Cl2, Cs2CO3, dioxane, 110 °C, 18 h, 55%–78%; (c) DIBAL-H, anhydrous THF, ‒45–0 °C, 12 h, 45%–70%.

2.2. Antiviral (WT) activity and cytotoxicity evaluation

All these new compounds (9a–9o) were surveyed for their inhition of WT HIV-l and cytotoxicity in MT-4 cells, and nevirapine (NVP), efavirenz (EFV), and etravirine (ETR) were selected as the controls. The experimental data were outlined in Table 1. Many of them displayed prominent inhibition of WT HIV-1 (EC50 = 0.9–305.9 nmol/L) and acceptable selectivity index (SI = 207–256,438). Among the 4-cyanophenyl-containing derivatives, 9a–9g exhibited excellent antiviral ability with the anti-HIV-1 EC50 values below 4 nmol/L. Compound 9a with a dimethyl wing on the different side of 4-cyanophenyl group had potent anti-HIV efficacy at the single-digit level (EC50 = 2.5 nmol/L), but with an unsatisfactory CC50 of 15.6 μmol/L. Replacing the dimethyl moiety of 9a with a methyl, methoxyl, fluoro, chloro, trifluoromethyl, or difluoro group, respectively, gave 9b–9g with 1- to 2.7-fold enhanced antiviral potency, except for the fluorine-substituted derivative 9d with slightly decreased activity (EC50 = 3.9 nmol/L). These derivatives exhibited significantly reduced cytotoxicity compared to 9a. Remarkably, compound 9g with a difluoro moiety exhibited picomolar anti-HIV-1 activity (EC50 = 0.9 nmol/L) and the highest selectivity index (SI = 256,438), making it a promising candidate for further investigation. Then, 3/4-pyridyl ring was introduced as a traditional bioisosterism of 4-cyanophenyl to study their anti-HIV ability. Compounds 9h–9l containing a 4-pyridinyl group maintained strong potency (EC50 = 0.9–18.2 nmol/L). However, 3-pyridyl-biphenyl-DAPYs (9m–9o) showed reduced anti-HIV activity at moderate nanomolar level (EC50 = 60.3–305.9 nmol/L). Among them, compound 9l exhibited similar antiviral potency (EC50 = 0.9 nmol/L) but higher cytotoxicity (CC50 = 128.3 μmol/L), compared with 9g.

Table 1.

Anti-HIV-1 activity and cytotoxicity of 9a–9o in MT-4 cells.

| Compd. | R | Ar | WT |

CC50 (μmol/L)b | SIc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (nmol/L)a | |||||

| 9a | di-Me | 4-Cyanophenyl | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 15.6 ± 4.6 | 6343 |

| 9b | Me | 4-Cyanophenyl | 1.2 ± 0.1 | >46.2 | >38,095 |

| 9c | OMe | 4-Cyanophenyl | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 258.0 ± 1.2 | 149,540 |

| 9d | F | 4-Cyanophenyl | 3.9 ± 0.4 | >45.8 | >11,594 |

| 9e | Cl | 4-Cyanophenyl | 2.6 ± 0.5 | >44.1 | >17,021 |

| 9f | CF3 | 4-Cyanophenyl | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 14.6 ± 3.1 | 7891 |

| 9g | di-F | 4-Cyanophenyl | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 225.4 ± 3.9 | 256,438 |

| 9h | di-Me | 4-Pyridyl | 7.1 ± 3.0 | 220.6 ± 12.5 | 30,868 |

| 9i | OMe | 4-Pyridyl | 18.2 ± 6.8 | 30.5 ± 3.4 | 1679 |

| 9j | F | 4-Pyridyl | 4.7 ± 0.7 | >48.4 | >10,256 |

| 9k | Cl | 4-Pyridyl | 4.9 ± 0.9 | 264.5 ± 10.2 | 53,539 |

| 9l | di-F | 4-Pyridyl | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 128.3 ± 5.5 | 138,219 |

| 9m | F | 3-Pyridyl | 305.9 ± 43.6 | 178.3 ± 32.9 | 583 |

| 9n | Cl | 3-Pyridyl | 60.3 ± 6.3 | >291.3 | >4831 |

| 9o | di-F | 3-Pyridyl | 65 ± 9 | 13.5 ± 0.3 | 207 |

| NVP | 293 ± 0.1 | >15.0 | >51 | ||

| EFV | 7 ± 0.0 | >6.3 | >863 | ||

| ETR | 6 ± 0.0 | >4.6 | >833 |

Concentration required to achieve 50% protection of MT-4 cells against HIV-induced cytopathic effect, as determined by the MTT method; values are the mean ± SD of at least two parallel tests.

Concentration required to reduce the viability of uninfected cells by 50%, as determined by the MTT method, and values were averaged from at least four independent experiments.

Selectivity index (SI): CC50/EC50.

2.3. Effect of 9a–9g on HIV-1 mutants

These biphenyl-DAPYs were further evaluated for effect on five common mutant strains. As described in Table 2, compounds 9a–9g bearing a 4-cyanophenyl group were more active than the heteroaromatic-biphenyl-DAPYs (9h–9o), and, especially, the antiviral ability of the 3-pyridyl-containing analogs (9m–9o) was significantly damaged. Compounds 9a–9g were active against mutants K103N, L100I, E138K, and Y181C, with EC50 of 1.9–901 nmol/L. However, these derivatives were little sensitive to Y188L, except for 9a (EC50 = 33 nmol/L). It should be noted that 9g had the same inhibitory effect as ETR on L100I, Y181C, K103N, and E138K mutants, but the inhibitory effect on Y188L was weakened.

Table 2.

Effect of 9a–9o on HIV-1 mutants.

| Compd. | EC50 (nmol/L)a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L100I | K103N | Y181C | Y188L | E138K | |

| 9a | 6.3 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 16.1 ± 2.3 | 33.0 ± 4.0 | 6.5 ± 0.5 |

| 9b | 18.1 ± 3.4 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 11.0 ± 0.3 | 144 ± 25.9 | 3.6 ± 0.7 |

| 9c | 20.5 ± 1.3 | 6.5 ± 0.2 | 27.6 ± 3.0 | 137 ± 8.1 | 19.4 ± 4.8 |

| 9d | 117 ± 17.7 | 14.4 ± 1.5 | 901 ± 208 | 41,793 ± 509 | 34.9 ± 3.2 |

| 9e | 18.5 ± 3.6 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 22.5 ± 3.5 | 564 ± 97.0 | 11.0 ± 2.1 |

| 9f | 11.1 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 29.9 ± 1.9 | 85.3 ± 8.4 | 7.9 ± 0.2 |

| 9g | 8.2 ± 1.4 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 15.4 ± 1.0 | 161 ± 27.6 | 3.5 ± 0.8 |

| 9h | 323 ± 44.5 | 20.1 ± 3.0 | 274 ± 7.7 | 1584 ± 103.2 | 38.9 ± 4.1 |

| 9i | 560 ± 137 | 95.6 ± 17.6 | 383 ± 15.0 | 1753 ± 122.6 | 217 ± 18.4 |

| 9j | 327 ± 44.9 | 35.1 ± 8.1 | 350 ± 21.2 | >48,410 | 42.4 ± 6.7 |

| 9k | 327 ± 54.8 | 35.4 ± 12.3 | 355 ± 12.6 | 42,967 ± 532 | 45.9 ± 5.9 |

| 9l | 22.2 ± 6.2 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 50.7 ± 3.8 | 720 ± 272 | 13.6 ± 1.2 |

| 9m | 13704 ± 1137 | 1691 ± 165 | 46,560 ± 1255 | >178,250 | 2492 ± 388 |

| 9n | 1996 ± 275 | 396 ± 42.1 | 6148 ± 316 | >13,450 | 490 ± 54.2 |

| 9o | 2658 ± 252 | 399 ± 30.7 | 2689 ± 255 | 151,258 ± 48,209 | 396 ± 17.1 |

| NVP | 2100 ± 750 | >10,080 | >15,870 | >15,870 | 2100 ± 30 |

| EFV | 440 ± 70 | 102 ± 50. | 7 ± 0.0 | 290 ± 40 | 6 ± 0.0 |

| ETR | 7 ± 0.0 | 3 ± 0.0 | 12 ± 10 | 20 ± 10 | 7 ± 10 |

EC50: The effective concentration required to protect MT-4 cells against viral cytopathicity by 50%, and values were averaged from at least three independent experiments.

2.4. Effect of 9a‒9g on WT HIV-1 RT

Next, we surveyed the effect of 9a–9g on WT HIV-1 RT. The results organized in Table 3 indicated that these derivatives exerted excellent nanomolar inhibition of WT HIV-1 RT with IC50 of 21–35 nmol/L. Especially, 9g was stronger (IC50 = 21 nmol/L) than NVP but was almost equally potent to that of EFV and ETR.

Table 3.

Effect of 9a‒9g on WT HIV-1 RT.

| Compd. | IC50 (μmol/L)a | Compd. | IC50 (μmol/L)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9a | 0.035 ± 0.008 | 9f | 0.021 ± 0.006 |

| 9b | 0.027 ± 0.002 | 9g | 0.021 ± 0.001 |

| 9c | 0.021 ± 0.008 | NVP | 0.404 ± 0.07 |

| 9d | 0.033 ± 0.002 | EFV | 0.030 ± 0.02 |

| 9e | 0.029 ± 0.003 | ETR | 0.011 ± 0.01 |

IC50: inhibitory concentration of test compound required to inhibit wild-type HIV-1 reverse transcriptase polymerase activity by 50%. Values are the mean ± SD of at least two parallel tests. The data were obtained from the same laboratory (Prof. Erik De Clercq, Rega Institute for Medical Research).

2.5. Molecular docking

Molecular docking was further performed by Schrödinger Bio-Luminate to elucidate the rationale for 9g with the most significant inhibitory activity25. The complex (PDB code: 2ZD1) was selected in this work, and the classical mutants (K103N, L100I, Y188L, Y181C, and E138K) were produced by point-specific mutations of 2ZD1. Compound 9g was predicted to insert into the binding pocket of RT with a typical binding conformation as a “U” mode. The biphenyl fragment nicely occupied the hydrophobic subpocket, generated by Y188, Y181, W229, and F227. As shown in Fig. 3A, two classical hydrogen bonds were maintained between the ligand and K101 (NH⋯O distance = 1.8, N⋯HN distance = 2.1). Notably, a newly constructed hydrogen bond between the ligand and E138 was observed, which contributed to their increased antiviral efficacy. In addition, similar docking results were observed in the simulated complexes of 9g with L100I, Y181C, K103N, Y188L, and E138K, respectively (Fig. 3B‒F), and the indispensable binding force was retained, such as hydrogen bonds, electrostatic, hydrophobic interactions, and van der Waals. Particularly, despite the lack of hydrogen bond of 9g with K138, a supplementary water-mediated hydrogen-bonding network between the methylol group and K138 residue was formed, which was responsible for its excellent potency against E138K (EC50 = 3.5 nmol/L), 2-fold better than ETR (EC50 = 7 nmol/L).

Figure 3.

Simulated docking complexes of 9g with WT HIV-1 RT (A), L100I (B), K103N (C), Y181C (D), Y188L (E), and E138K (F), respectively.

2.6. Molecular dynamic simulations

Schrödinger Maestro 11.4 was applied to monitor the important interactions that occurred in molecular recognition and the protein-ligand complex (Fig. 4A‒D). The RMSD represents the conformational drift (protein and ligand) (Fig. 4A). The 9g–2ZD1 complex stabilized rapidly and the RMSD value for 9g was generally below the allowable limit of 3 Å within 50 ns molecular dynamic (MD) simulation. The simulated interaction modes were outlined in Fig. 4B‒D, showing the detailed interactions of the protein‒9g complex. Several classical interactions were observed throughout the MD simulation, including hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic, ionic, and water bridges. The value of the interaction fraction predicts the probability that a specific contact will occur during the simulation time. Values above 100% may be due to multiple interactions between protein and ligand. Consistent with our previous results, the two hydrogen bonds between 9g and the LYS101 (K101) backbone functioned for almost the entire 50 ns. A key hydrogen bond, formed by the ligand and E138, was almost consistently observed with a water-mediated hydrogen bond that occasionally occurred. A new water-bridge hydrogen bond of the complex occurred discontinuously, which was undetected in the docking analysis. Moreover, the crucial hydrophobic interactions of 9g with LEU100 (L100), TYR318 (Y318), TRP229 (W229), TYR188 (Y188), and TYR181 (Y181) occurred throughout most of the simulation time (Fig. 4B‒D).

Figure 4.

Molecular dynamic simulations of 9g with WT HIV-1 RT (PDB code: 2ZD1). (A) RMSD of 9g and the protein; (B and C) Ligand‒protein contacts analysis of MD trajectory; (D) The two-dimensional interaction diagram and interactions which occur over 30.0% of 50 ns were presented.

2.7. In vitro CYP enzymatic inhibitory activity

ETR and RPV were stimulators of CYP enzymes that induced various drug‒drug interactions4,26. Then, several classical CYP isoforms were selected to evaluate their sensitivity toward 9g, and the data were organized in Table 4. It was found that 9g was not sensitive to CYP2C9, CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP3A4M, and CYP3A4T with IC50 of above 25 μmol/L. Additionally, 9g weakly inhibited CYP2C19 (IC50 = 14 μmol/L), which was very sensitive to RPV (IC50 = 0.34 μmol/L). These data supported that 9g may not induce significant drug‒drug interactions.

Table 4.

Effect of 9g on CYP enzymes.

| Compd. | IC50 (μmol/L) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP1A2 | CYP2C9 | CYP2C19 | CYP2D6 | CYP3A4-T | CYP3A4-M | |

| 9g | >25 | >25 | 14.0 | >25 | >25 | >25 |

| RPV26 | 9.11 | 0.346 | 0.335 | 3.41 | 2.17 | |

| Reference | 0.042a | 0.529b | 1.57c | 0.0397d | 0.0452e | 0.0739f |

Phenacetin.

Tolbutamide

Mephenytoin

Dextromethorphan.

Testosterone, and.

Midazolam were selected as the reference drugs (substrate midazolam).

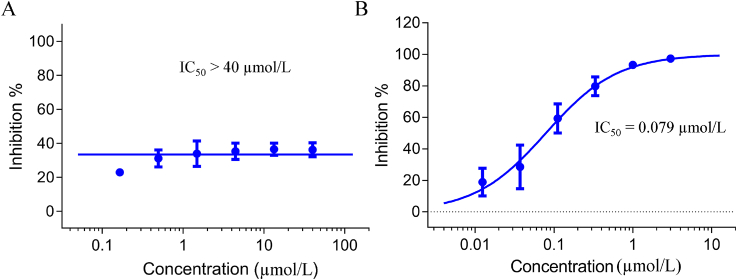

2.8. Effect of compound 9g on hERG

The human ether-à-go-go-related gene (hERG) blocker was associated with cardiac arrhythmias27. RPV displayed nanomolar inhibition of hERG (IC50 = 0.50 μmol/L)28. To further assess the potential toxicity of 9g to hERG, we conducted the relevant assay with 9g and the positive control cisapride in CHO-hERG cells, and the results were organized in Fig. 5. The efficacy of cisapride was assayed by CHO-hERG cell model as the positive agent. As shown in Fig. 5A, compound 9g had no significant inhibition of hERG at 40 μmol/L, and its hERG toxicity was lower than cisapride (IC50 = 0.079 μmol/L), further demonstrating its security.

Figure 5.

Effect of compound 9g (A) and cisapride (B) on hERG in CHO-hERG cells.

2.9. The metabolic stability of 9g in different species

Next, the metabolic stability of 9g was assessed in three different species, including monkey, dog, and human, which were collected in Table 5. The metabolic stability of compound 9g in three species was significantly different. Compound 9g displayed poor metabolic stability with a short half-life (t1/2 = 26.1 min) and high clearance rate (Clint = 80.5 mL/min/kg) in monkey liver microsome, while moderate metabolic stability was presented in dog liver microsome (t1/2 = 71.2 min, Clint = 29.5 mL/min/kg). Pleasingly, compared with compound 5 (t1/2 = 138 min, Clint = 5.0 mL/min/kg)21, the metabolic stability of 9g in human liver microsome was significantly enhanced, characterized by much longer half-life (t1/2 = 2754 min) and lower clearance (Clint = 0.763 mL/min/kg), featuring an excellent MF value of 96.3%.

Table 5.

Liver microsomal stability of 9g in different species.

| Compd. | Species | Liver microsomal stability |

MF (%)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t1/2 (min) | Clint(mic) (mL/min/kg) | Clint(hep) (mL/min/kg) | |||

| 5 | Human | 138 | 5.0 | – | – |

| 9g | Monkey | 26.1 | 80.5 | 122 | 28.1 |

| Dog | 71.2 | 29.5 | 179 | 42.2 | |

| Human | 2754 | 0.763 | 56.2 | 96.3 | |

MF%: The parameter of liver microsomal stability, MF%>70% (excellent); 30% < MF% < 70% (good); MF% <30% (poor).

2.10. In vivo pharmacokinetics analysis

The pharmacokinetic (PK) profiles of 9g in Sprague−Dawley rats were also surveyed after intravenous or oral administration, respectively. The results collected in Table 6 indicated that 9g exhibited better PK profiles than 521. After intravenously administrated, the maximum concentration of 9g (Cmax) reached 296 ng/mL, the half-life was 1.5 h, and the mean residence time (MRT) was 1.19 h. When 10.0 mg/kg of 9g was orally administered, the maximum concentration (Cmax) was 39.3 ng/mL at 0.83 h and the half-life was 5.21 h. It has been reported that the F value of RPV cannot be accurately determined, and the F value of ETR remains unknown29,30. Therefore, the low oral bioavailability (F = 8.01%) requires further optimization, albeit with a slight improvement relative to compound 5 (F = 2.39%).

Table 6.

PK profile of 9g in rata.

| Parameter | 10.0 mg/kg (p.o.) | 1.0 mg/kg (i.v.) |

|---|---|---|

| t1/2 (h) | 5.21 ± 3.02 | 1.50 ± 0.14 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.83 ± 0.29 | 0.08 ± 0.00 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 39.3 ± 8.04 | 296 ± 79.4 |

| AUC0‒t (h·ng/mL) | 159 ± 48.7 | 244 ± 24.5 |

| AUC0‒∞ (h·ng/mL) | 198 ± 38.6 | 247 ± 25.8 |

| MRT0‒t (h) | 3.91 ± 2.38 | 1.19 ± 0.16 |

| MRT0‒∞ (h) | 6.80 ± 2.79 | 1.33 ± 0.21 |

| F (%) | 8.01 ± 0.02 |

p.o.: oral administration; i.v.: intravenous injection; t1/2: half-life; Tmax: time at peak concentration; Cmax: peak concentration; AUC: area under the concentration-time curve; MRT: mean residence time; F: oral bioavailability.

2.11. Acute toxicity assay of 9g

The acute toxicity of 9g was assayed in healthy mice. As shown in Fig. 6, intragastric administration of 9g (2 g/kg) did not cause mice death. The body weight of the experimental group (male and female) increased gradually within two weeks, and the growth trend was better than the control group (Fig. 6A‒B). No behavioral abnormalities occurred during the assay. Therefore, 9g was well tolerated for a single oral administration of 2 g/kg. Meanwhile, hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining test was also carried out. The results suggested that no obvious pathological injury was found in six organs, as shown in Fig. 6C.

Figure 6.

Changes of body weight over time in female (A) and male (B) mice; (C) Histological changes by HE staining (magnification: × 200).

3. Conclusions

In summary, a series of novel hydroxymethyl-biphenyl-diarylpyrimidines were synthesized to enhance the metabolic stability of compound 5. Most of these derivatives exhibited excellent anti-HIV-1 potency and low cytotoxicity. Especially, the most potent compound 9g was picomolar inhibition of WT HIV-1 (EC50 = 0.9 nmol/L) and low nanomolar inhibition of five tested drug-resistant mutant strains, coupled with particularly low cytotoxicity and good selectivity (CC50 = 264 μmol/L, SI = 256,438). It was almost equally potent to that of EFV and ETR in terms of WT HIV-1 RT inhibition (IC50 = 21 nmol/L). Molecular docking analysis showed that the newly introduced hydroxymethyl group of 9g nicely filled the subpocket, encircled by K101, E138, V179, and Y181, and interacted with E138 through a newly constructed hydrogen bond. Compound 9g displayed significantly different in vitro metabolic stability in three species (dog, monkey, and human). Pleasingly, compared with compound 5 (t1/2 = 138 min, Clint = 5.0 mL/min/kg), the metabolic stability of 9g in human liver microsome was remarkably enhanced with a much longer half-life (t1/2 = 2754 min) and lower clearance (Clint = 0.763 mL/min/kg). In addition, both CYP enzymes and hERG were not sensitive to 9g. The acute toxicity assay revealed that no death and obvious pathological damage occurred at a single oral administration of 2 g/kg. These findings will further guide and accelerate the development of new-generation anti-HIV-1 drugs.

4. Experimental

4.1. Chemistry

4.1.1. Synthetic protocol of 7a‒7g and 8a‒8o

The detailed synthetic protocol followed our previously reported method23,24.

4.1.2. Synthetic protocol of 9a–9o

To a solution of 9a–9o (0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) in dry THF was slowly added DIBAL-H (2.5 mmol, 5.0 equiv.) at ‒45 °C under N2 protection, which was raised to 0 °C after reaction for 2 h. Upon completion, quench the reaction with 1.5 mL MeOH:H2O (v/v = 2:1) at ‒45 °C, followed by the addition of potassium sodium tartrate solution for another 3 h. The crude product was extracted with ethyl acetate (15 mL × 3) and purified to deliver compounds 9a‒9o.

4′-((2-((4-Cyanophenyl)amino)-5-(hydroxymethyl)pyrimidin-4-yl)oxy)-3′,5′-dimethyl-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (9a), white solid, yield 54%, mp 264.7–266.9 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 10.07 (1H, s), 8.45 (1H, s), 8.05–7.92 (4H, m), 7.65 (2H, d, J = 5.7 Hz), 7.55 (2H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.47 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.35 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 5.31 (1H, s), 4.65 (2H, s), 2.15 (6H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 191.12, 166.29, 158.72, 158.65, 150.89, 145.17, 144.53, 135.97, 133.34, 132.94, 131.80, 130.80, 129.59, 127.92, 127.86, 127.67, 119.83, 119.36, 118.43, 117.95, 113.27, 110.39, 102.55, 56.21, 16.64. MS (ESI) m/z C27H21N5O2: calcd 447.17; found, 448.1614 [M + 1]+.

4′-((2-((4-Cyanophenyl)amino)-5-(hydroxymethyl)pyrimidin-4-yl)oxy)-3′-methyl-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (9b), white solid, yield 45%, mp 249.0–250.3 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 10.06 (1H, s), 8.45 (1H, s), 7.96 (4H, s), 7.82 (1H, s), 7.78–7.69 (1H, m), 7.57 (2H, t, J = 10.7 Hz), 7.38 (1H, d, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.33 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 5.29 (1H, t, J = 5.3 Hz), 4.62 (2H, d, J = 4.9 Hz), 2.18 (3H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 191.29, 166.93, 158.87, 158.57, 152.61, 150.77, 146.84, 146.62, 135.21, 131.89, 130.81, 130.15, 129.66, 126.23, 123.91, 121.64, 118.06, 113.49, 56.19, 16.43. MS (ESI) m/z C26H19N5O2: calcd 433.15; found 434.1458 [M + 1]+.

4′-((2-((4-Cyanophenyl)amino)-5-(hydroxymethyl)pyrimidin-4-yl)oxy)-3′-methoxy-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (9c), white solid, yield 59%, mp 237.6–239.2 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 10.08 (1H, d, J = 15.0 Hz), 8.43 (1H, s), 8.01 (4H, dd, J = 20.9, 10.3 Hz), 7.59 (3H, d, J = 11.9 Hz), 7.51 (1H, d, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.44 (1H, d, J = 7.1 Hz), 7.40 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 7.35 (1H, t, J = 7.2 Hz), 5.28 (1H, d, J = 5.0 Hz), 4.60 (2H, s), 3.82 (3H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 191.30, 166.88, 158.47, 152.29, 146.67, 145.17, 144.56, 142.23, 133.34, 133.00, 130.84, 130.63, 129.61, 128.23, 128.19, 127.99, 124.34, 120.17, 118.42, 117.98, 113.41, 110.61, 102.52, 56.53, 56.08. MS (ESI) m/z C26H19N5O3: calcd 449.15; found, 450.1404 [M + 1]+.

4′-((2-((4-Cyanophenyl)amino)-5-(hydroxymethyl)pyrimidin-4-yl)oxy)-3′-fluoro-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (9d), white solid, yield 62%, mp 248.2–250.5 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 10.10 (1H, s), 8.48 (1H, s), 8.09–7.91 (5H, s), 7.74 (1H, s), 7.66–7.48 (4H, s), 7.41 (1H, s), 5.33 (1H, s), 4.60 (2H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 193.08, 166.42, 159.27, 158.40, 144.94, 143.03, 133.45, 133.04, 130.83, 130.69, 128.14, 127.96, 125.64, 124.46, 119.81, 119.20, 118.62, 118.17, 116.11, 115.91, 113.42, 111.16, 102.86, 55.98. MS (ESI) m/z C25H16FN5O2: calcd 437.13; found, 438.1198 [M + 1]+.

3′-Chloro-4′-((2-((4-cyanophenyl)amino)-5-(hydroxymethyl)pyrimidin-4-yl)oxy)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (9e), white solid, yield 52%, mp 240.8–242.9 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 10.10 (1H, d, J = 9.8 Hz), 8.49 (1H, s), 8.10 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz), 8.03 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz), 8.02 (1H, s), 7.98 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.90 (1H, dd, J = 8.4, 2.1 Hz), 7.58 (3H, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 7.41 (2H, d, J = 8.7 Hz), 5.35 (1H, t, J = 5.5 Hz), 4.63 (2H, d, J = 5.3 Hz). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 166.40, 159.05, 158.32, 149.37, 144.97, 142.88, 137.93, 133.46, 133.01, 129.28, 128.23, 127.84, 127.75, 125.81, 119.81, 119.19, 118.59, 113.55, 111.19, 102.80, 56.00. MS (ESI) m/z C25H16ClN5O2: calcd 453.10; found, 454.0900 [M + 1]+.

4′-((2-((4-Cyanophenyl)amino)-5-(hydroxymethyl)pyrimidin-4-yl)oxy)-3′-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (9f), white solid, yield 47%, mp 223.0–224.5 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 10.11 (1H, s), 8.50 (1H, s), 8.21 (2H, d, J = 12.2 Hz), 8.12–7.95 (4H, m), 7.71 (1H, s), 7.67–7.51 (3H, m), 7.46 (1H, s), 5.34 (1H, s), 4.61 (2H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 193.26, 191.39, 166.73, 158.96, 158.27, 146.40, 144.92, 142.85, 136.73, 133.52, 133.49, 133.11, 130.85, 130.73, 129.87, 128.44, 128.23, 126.78, 126.66, 119.83, 119.17, 118.66, 113.88, 111.34, 102.89, 55.90. MS (ESI) m/z C26H16F3N5O2: calcd 487.13; found, 488.1159 [M + 1]+.

4′-((2-((4-Cyanophenyl)amino)-5-(hydroxymethyl)pyrimidin-4-yl)oxy)-3′,5′-difluoro-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (9g), white solid, yield 61%, mp 257.9–259.0 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 10.21 (1H, s), 8.54 (1H, d, J = 4.1 Hz), 8.06 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz), 8.00 (2H, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 7.90 (2H, dd, J = 8.7, 3.6 Hz), 7.60 (2H, d, J = 8.7 Hz), 7.46 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 5.38 (1H, t, J = 5.5 Hz), 4.62 (2H, d, J = 5.3 Hz). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 165.66, 159.88, 158.42, 154.50, 144.77, 141.90, 133.48, 133.10, 128.24, 119.74, 119.07, 118.69, 113.14, 112.11, 111.88, 111.75, 103.11, 55.81. MS (ESI) m/z C25H15F2N5O2: calcd 455.12; found, 456.1103 [M + 1]+.

4-((4-(2,6-Dimethyl-4-(pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)-5-(hydroxymethyl)pyrimidin-2-yl)amino)benzonitrile (9h), white solid, yield 50%, mp 279.1–281.5 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 10.11 (1H, s), 9.65 (1H, s), 8.66 (2H, s), 8.46 (1H, s), 7.77 (2H, d, J = 3.7 Hz), 7.70 (2H, s), 7.55 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.48 (2H, d, J = 7.9 Hz), 5.31 (1H, s), 4.65 (2H, s), 2.16 (6H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 191.24, 166.29, 158.85, 158.72, 151.27, 150.73, 146.97, 146.66, 134.97, 131.89, 130.80, 129.61, 127.58, 121.62, 117.95, 113.14, 56.22, 16.63. MS (ESI) m/z C25H21N5O2: calcd 423.17; found, 424.1637 [M + 1]+.

4-((5-(Hydroxymethyl)-4-(2-methoxy-4-(pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)pyrimidin-2-yl)amino)benzonitrile (9i), white solid, yield 63%, mp 212.0–213.6 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 10.10 (1H, s), 9.67 (1H, s), 8.70 (2H, dd, J = 4.6, 1.5 Hz), 8.45 (1H, s), 7.84 (2H, dd, J = 4.5, 1.6 Hz), 7.65 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz), 7.59 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.54–7.48 (3H, m), 7.38 (1H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), 5.30 (1H, t, J = 5.5 Hz), 4.61 (2H, d, J = 5.4 Hz), 3.83 (3H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 191.28, 166.87, 158.62, 158.48, 152.41, 150.74, 147.01, 146.67, 142.64, 136.54, 130.84, 129.63, 124.44, 121.87, 119.95, 117.99, 113.29, 112.12, 56.58, 56.09. MS (ESI) m/z C24H19N5O3: calcd 426.15; found, 427.1970 [M + 1]+.

4-((4-(2-Fluoro-4-(pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)-5-(hydroxymethyl)pyrimidin-2-yl)amino)benzonitrile (9j), white solid, yield 65%, mp 225.4–226.7 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 10.16 (1H, d, J = 16.5 Hz), 9.68 (1H, s), 8.71 (2H, dd, J = 4.6, 1.5 Hz), 8.50 (1H, d, J = 4.0 Hz), 8.02 (1H, dd, J = 11.7, 2.0 Hz), 7.85–7.81 (3H, m), 7.63–7.57 (3H, m), 7.55 (1H, s), 7.43 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 5.34 (1H, t, J = 5.3 Hz), 4.62 (2H, d, J = 4.4 Hz). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 191.34, 166.44, 159.37, 158.48, 150.90, 146.41, 145.53, 137.01, 133.05, 130.84, 129.85, 125.77, 124.22, 121.71, 118.63, 118.17, 115.91, 115.71, 113.27, 55.98. MS (ESI) m/z C23H16FN5O2: calcd 413.13; found, 414.1560 [M + 1]+.

4-((4-(2-Chloro-4-(pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)-5-(hydroxymethyl)pyrimidin-2-yl)amino)benzonitrile (9k), white solid, yield 48%, mp 244.8–246.2 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 10.16 (1H, s), 9.67 (1H, s), 8.71 (2H, d, J = 4.8 Hz), 8.50 (1H, s), 8.17 (1H, s), 7.97 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.85 (2H, d, J = 4.9 Hz), 7.62 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.58 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.52 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 5.35 (1H, s), 4.64 (2H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 191.31, 166.41, 159.15, 158.40, 150.89, 149.81, 146.45, 145.40, 136.97, 130.81, 129.80, 129.08, 127.92, 127.63, 125.95, 121.79, 118.13, 113.39, 56.01. MS (ESI) m/z C23H16ClN5O2: calcd 429.10; found, 430.0901 [M + 1]+.

4-((4-(2,6-Difluoro-4-(pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)-5-(hydroxymethyl)pyrimidin-2-yl)amino)benzonitrile (9l), white solid, yield 60%, mp 223.5–225.6 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 10.21 (1H, s), 8.71 (2H, s), 8.53 (1H, s), 8.02–7.80 (4H, m), 7.65–7.40 (4H, m), 5.37 (1H, s), 4.61 (2H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 191.27, 166.98, 158.81, 158.59, 151.80, 148.96, 148.07, 146.65, 135.45, 135.16, 134.55, 131.75, 130.82, 130.17, 129.65, 126.21, 124.41, 123.81, 118.08, 113.51, 56.21. MS (ESI) m/z C23H15F2N5O2: calcd 431.12; found, 432.1160 [M + 1]+.

4-((4-(2-Fluoro-4-(pyridin-3-yl)phenoxy)-5-(hydroxymethyl)pyrimidin-2-yl)amino)benzonitrile (9m), white solid, yield 65%, mp 201.7–203.5 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 10.18 (1H, s), 9.68 (1H, s), 9.03 (1H, s), 8.64 (1H, s), 8.50 (1H, s), 8.20 (1H, s), 7.94 (1H, s), 7.74 (1H, s), 7.65–7.45 (6H, m), 5.33 (1H, s), 4.62 (2H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 191.31, 166.49, 159.31, 158.50, 156.12, 153.66, 149.55, 148.19, 146.44, 140.09, 139.97, 136.97, 134.76, 134.19, 130.85, 129.84, 125.67, 124.46, 124.15, 118.17, 115.84, 115.65, 113.29, 56.00. MS (ESI) m/z C23H16FN5O2: calcd 413.13; found, 414.1560 [M + 1]+.

4-((4-(2,6-Difluoro-4-(pyridin-3-yl)phenoxy)-5-(hydroxymethyl)pyrimidin-2-yl)amino)benzonitrile (9n), white solid, yield 70%, mp 212.5–213.7 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 10.16 (1H, s), 9.67 (1H, s), 9.02 (1H, s), 8.64 (1H, s), 8.50 (1H, s), 8.21 (1H, d, J = 7.1 Hz), 8.10 (1H, s), 7.89 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.64–7.49 (6H, m), 5.35 (1H, s), 4.64 (2H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 191.29, 166.46, 159.09, 158.41, 149.56, 148.99, 148.22, 146.47, 136.91, 134.85, 134.06, 130.82, 129.78, 129.00, 127.76, 127.59, 125.85, 124.46, 118.13, 113.40, 56.02. MS (ESI) m/z C23H16ClN5O2: calcd 429.10; found, 430.0905 [M + 1]+.

4-((4-(2-Chloro-4-(pyridin-3-yl)phenoxy)-5-(hydroxymethyl)pyrimidin-2-yl)amino)benzonitrile (9o), white solid, yield 49%, mp 216.5–218.2 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 10.26 (1H, s), 9.68 (1H, s), 9.07 (1H, s), 8.75–8.28 (2H, m), 8.24 (1H, s), 7.88 (2H, s), 7.65–7.45 (5H, m), 5.39 (1H, s), 4.63 (2H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 191.30, 165.72, 159.92, 158.52, 154.54, 150.08, 148.26, 146.25, 134.86, 133.19, 130.86, 130.01, 128.52, 124.44, 118.23, 113.01, 111.77, 111.54, 55.84. MS (ESI) m/z C23H15F2N5O2: calcd 431.12; found, 432.1107 [M + 1]+.

4.2. In vitro anti-HIV assay

Evaluation of the antiviral activity of the compounds against WT HIV-1, and mutant strains (L100I, K103N, E138K, and Y181C) in MT-4 cells was performed using the MTT assay as previously described31. Stock solutions of test compounds were added in 25 μL volumes to two series of triplicate wells to allow simultaneous evaluation of their effects on mock- and HIV-infected cells at the beginning of each experiment. Serial 5-fold dilutions of test compounds were made directly in flat-bottomed 96-well microtiter trays using a Biomek 3000 robot (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA, USA). Standard concentrations tested were 125, 25, 5, 1, 0.2, 0.04, 0.008, 0.0016 μg/mL, thus 8 concentrations were tested. Untreated HIV- and mock-infected cell samples were included as controls. HIV stock (50 μL) at 100–300 CCID50 (50% cell culture infectious doses) or culture medium was added to either the infected or mock-infected wells of the microtiter tray. Mock-infected cells were used to evaluate the effects of test compound on uninfected cells to assess the cytotoxicity of the test compounds. Exponentially growing MT-4 cells were centrifuged for 5 min at 220×g and the supernatant was discarded. The MT-4 cells were resuspended at 6 × 105 cells/mL and 50 μL volumes were transferred to the microtiter tray wells. Five days after infection, the viability of mock-and HIV-infected cells was examined spectrophotometrically using the MTT assay. The MTT assay is based on the reduction of yellow colored 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) (Acros Organics) by mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity in metabolically active cells to a blue-purple formazan that can be measured spectrophotometrically. The absorbances were read in an eight-channel computer-controlled photometer (Infinite M1000, Tecan), at two wavelengths (540 and 690 nm). All data were calculated using the median absorbance value of three wells. The 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) was defined as the concentration of the test compound that reduced the absorbance (OD540) of the mock-infected control sample by 50%. The concentration achieving 50% protection against the cytopathic effect of the virus in infected cells was defined as the 50% effective concentration (EC50).

4.3. HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibition assay

Recombinant wild-type p66/p51 HIV-1 RT was expressed and purified in our lab32. The RT assay is performed with the EnzCheck Reverse Transcriptase Assay kit (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen), as described by the manufacturer. The assay is based on the dsDNA quantitation reagent PicoGreen. This reagent shows a pronounced increase in fluorescence signal upon binding to dsDNA or RNA‒DNA heteroduplexes. Single-stranded nucleic acids generate only minor fluorescence signal enhancement when a sufficiently high dye: base pair ratio is applied33. This condition is met in the assay. A poly(rA) template of approximately 350 bases long, and an oligo(dT)16 primer, are annealed in a molar ratio of 1:1.2 (60 min at room temperature). Fifty-two ng of the RNA/DNA is brought into each well of a 96-well plate in a volume of 20 μL polymerization buffer (60 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 60 mmol/L KCl, 8 mmol/L MgCl2, 13 mmol/L DTT, 100 μmol/L dTTP, pH 8.1). The inhibitor concentrations tested were: 120, 24, 4.8, 0.96, 0.192, 0.038, 0.0077, and 0.0015 μg/mL, therefore 8 concentrations of the compounds were tested. 5 μL of RT enzyme solution, diluted to a suitable concentration in enzyme dilution buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 20% glycerol, 2 mmol/L DTT, pH 7.6), is added. The reactions are incubated at 25 °C for 40 min and then stopped by the addition of EDTA (15 mmol/L fc). Heteroduplexes are then detected by the addition of PicoGreen. Signals are read using an excitation wavelength of 490 nm and emission detection at 523 nm using a spectrofluorometer (Safire 2, Tecan). To test the activity of compounds against RT, 1 μL of compound in DMSO is added to each well before the addition of RT enzyme solution. Control wells without compound contain the same amount of DMSO. Results are expressed as relative fluorescence and the fluorescence signal of the reaction mix with compound divided by the signal of the same reaction mix without compound.

4.4. hERG channel qpatch assay

9g was dissolved in DMSO and prepared to a 20 mmol/L stock solution. Before assay, the test compound 9g stock solution was thawed and 3-fold serial diluted to work solution in DMSO, then 500-fold diluted into external solution to get the desired final solutions. The DMSO concentration in the final solution is 0.2%, which has no effect on hERG currents. hERG-CHO cells (constructed in-house) were cultured in T75 flasks to maximum of 70%–80% confluence at 37 °C 5% CO2 incubator. The culture media (F-12 medium (Invitrogen 11765062, ThermoFisher, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen 10099141, ThermoFisher, USA), 100 g/mL G418 (Invitrogen 11811023, ThermoFisher, USA) and 100 g/mL Hygromycin B (Invitrogen 10687010, ThermoFisher, USA) was removed and the hERG-CHO cells were washed with 7 mL PBS. Then the cells were dissociated with 3 mL Detachin reagent in 37 °C incubator for 3 min, and 7 mL medium was added to gently suspend cells by pipetting up and down several times. Finally, the cells were harvested by 800 rpm/min centrifuge and adjusted to 2−5 million cells/mL for automated Qpatch 16x experiments (Qpatch 16x, Sophion, Denmark).

The hERG currents were recorded in the whole-cell patch clamp configuration on QPatch 16x using single-hole QPlate. The cells were voltage clamped at a holding potential of −80 mV. hERG current was activated by depolarizing at +20 mV for 5 s, after which the current was taken back to −50 mV for 5 s to remove the inactivation and observe the deactivating tail current. The peak size of tail current was used to quantify hERG current amplitude. Each concentration of 9g was tested on at least 3 cells. Raw data has been included statistics as membrane resistance Rm > 100 MΩ and tail current amplitude >300 pA in control.

4.5. Cytochrome P450 inhibition assay

Compound 9g at eight concentrations (0, 0.01, 0.02, 0.20, 1.00, 2.00, 10.0, 30.0 μmol/L) was incubated with human liver microsomes (0.25−1.25 mg/mL) and NADPH (5 mmol/L) in the presence of CYP1A2 probe substrate phenacetin (25 μmol/L), CYP2C9 probe substrate Tolbutamide (100 μmol/L), CYP2C19 probe substrate S-mephenytoin (40 μmol/L), CYP2D6 probe substrate dextromethorphan (5 μmol/L), CYP3A4M probe substrate midazolam (5 μmol/L), and CYP3A4T probe substrate testosterone (45 μmol/L) for 15−45 min in a 37 °C water bath. Then, the selective CYP1A2 inhibitor α-naphthoflavone, the selective CYP2C9 inhibitor sulfaphenazole, the selective CYP2C19 inhibitor nootkatone, the selective CYP2D6 inhibitor quinidine, and the selective CYP3A4 inhibitor ketoconazole were screened alongside the test compound as a positive control. Methanol-containing Tolbutamide as an internal standard was used for stopping the reaction. Positive controls, duplicates of 9g for each concentration, were prepared in parallel (n = 2).

4.6. PK study

Male Sprague−Dawley rats (180−200 g) were randomly divided into groups (n = 3) to receive the dosage level (1 mg/kg, i.v.) or the medium dosage level (10 mg/kg, p.o.) of compound. The sample was suspended in a mixture of DMSO, polyethylene glycol (PEG) 400, and normal saline (10/40/50, v/v/v) before the experiment. Compound was administered to rats by gavage. Blood samples were collected from the sinus jugular into heparinized centrifugation tubes at 5, 15, 30 min, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 24 h after dosing. The samples were then centrifuged to separate plasma, which was stored at −80 °C until analysis. LCMS analysis was used to determine the concentration of compound in plasma. Briefly, 25 μL of plasma was added to 25 μL of internal standard and 200 μL of methanol in a 5 mL centrifugation tube, which was centrifuged at 3000g for 10 min. The supernatant layer was collected, and a 20 μL aliquot was injected for LCMS analysis. Standard curves in blood were generated by the addition of various concentrations of compound together with internal standard to blank plasma. All samples were quantified with a Shimadzu LC-20AD. The mobile phase was methanol/1.5% acetic acid (50:50, v/v) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min, and the test wavelength was 225 nm. All blood samples were centrifuged in an Eppendorf 5430R centrifuge and quantified by Shimadzu LC-20AD. PK status was calculated with WinNonlin 6.3 software using the NCA model.

4.7. Acute toxicity assay and HE staining of organ tissue

Six Male Sprague−Dawley rats (180−220 g) aged 6−8 weeks were obtained from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Rats were randomly divided into two groups (n = 2) to receive intravenous (1 mg/kg) or oral administration (5 mg/kg) and maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights-on at 7:00 a.m.) in a temperature-controlled environment with free access to food and water. All animal treatments were performed under the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals using an approved animal protocol by the Fudan University Committee on Animal Care (2020CHEM-JS-008). The animals were kept in an airconditioned rat room and used to determine the kinetic profiles. Solutions of 9g were prepared in a mixture of polyethylene glycol (PEG-400)/normal saline/DMSO (75/20/5, v/v/v) before the experiment. Blood samples (250 μL each time) from the intravenous or oral administration group were collected from the posterior orbital venous plexus into heparinized centrifugation tubes at 5, 15, 30 min, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h after dosing. Plasma samples were obtained by centrifugation at 6000 rpm, 4 °C for 3 min, and immediately frozen (−20 °C). LC−MS analysis was used to determine the concentration of 9g in plasma. Standard curves for 9g in blood were generated by the addition of various concentrations together with an internal standard to blank plasma. All samples were quantified with a Shimadzu LC-30AD. The mobile phase was methanol/0.1%formic acid at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. All blood samples were centrifuged in an Eppendorf 5424R centrifuge and quantified by the Shimadzu LC-20AD. Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using WinNolin 8.2 software.

4.8. Other protocols

Other experimental methods were presented in Supporting Information.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22077018). We also express our gratitude to Fudan University for providing the sources of molecular modeling and molecular dynamic simulations suite (Schrödinger Maestro).

Author contributions

Ya-Li Sang conducted the synthesis and structure confirmation. Erik De Clercq and Christophe Pannecouque completed the biological evaluation. Shuai Wang and Ya-Li Sang conducted drugability evaluation experiments and molecular docking studies. Shuai Wang, Ya-Li Sang and Fen-Er Chen were in charge of writing this article and summarizing the data. Fen-Er Chen conceived the project and provided the resources, supervision, and funding assistance. All authors critically evaluated the manuscript prior to submission.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2023.03.022.

Contributor Information

Shuai Wang, Email: shuaiwang@fudan.edu.cn.

Fen-Er Chen, Email: rfchen@fudan.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supporting information

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Global HIV & AIDS statistics-Fact sheet 2022. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf

- 2.Jin K., Liu M., Zhuang C., De Clercq E., Pannecouque C., Meng G., et al. Improving the positional adaptability: structure-based design of biphenyl-substituted diaryltriazines as novel non-nucleoside HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:344–357. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han S., Sang Y., Wu Y., Tao Y., Pannecouque C., De Clercq E., et al. Molecular hybridization-inspired optimization of diarylbenzopyrimidines as HIV-1 nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors with improved activity against K103N and E138K mutants and pharmacokinetic profiles. ACS Infect Dis. 2020;6:787–801. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.9b00229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang D., Feng D., Sun Y., Fang Z., Wei F., De Clercq E., et al. Structure-based bioisosterism yields HIV-1 NNRTIs with improved drug-resistance profiles and favorable pharmacokinetic properties. J Med Chem. 2020;63:4837–4848. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang B., Ginex T., Luque F.J., Jiang X., Gao P., Zhang J., et al. Structure-based design and discovery of pyridyl-bearing fused bicyclic HIV-1 inhibitors: synthesis, biological characterization, and molecular modeling studies. J Med Chem. 2021;64:13604–13621. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X. Anti-retroviral drugs: current state and development in the next decade. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2018;8:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu N., Wei L., Huang L., Yu F., Zheng W., Qin B., et al. Novel HIV-1 non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor agents: optimization of diarylanilines with high potency against wild-type and rilpivirine-resistant E138K mutant virus. J Med Chem. 2016;59:3689–3704. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X., Ding L., Tao Y., Pannecouque C., De Clercq E., Zhuang C., et al. Bioisosterism-based design and enantiomeric profiling of chiral hydroxyl-substituted biphenyl-diarylpyrimidine nonnucleoside HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;202 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han S., Sang Y., Wu Y., Tao Y., Pannecouque C., De Clercq E., et al. Fragment hopping-based discovery of novel sulfinylacetamide-diarylpyrimidines (DAPYs) as HIV-1 nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;185 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang D., Ruiz F.X., Sun Y., Feng D., Jing L., Wang Z., et al. 2,4,5-Trisubstituted pyrimidines as potent HIV-1 NNRTIs: rational design, synthesis, activity evaluation, and crystallographic studies. J Med Chem. 2021;64:4239–4256. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z., Zalloum W.A., Wang W., Jiang X., De Clercq E., Pannecouque C., et al. Discovery of novel dihydrothiopyrano[4,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives as potent HIV-1 NNRTIs with significantly reduced hERG inhibitory activity and improved resistance profiles. J Med Chem. 2021;64:13658–13675. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li G., Wang Y., De Clercq E. Approved HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitors in the past decade. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:1567–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sang Y., Han S., Pannecouque C., De Clercq E., Zhuang C., Chen F. Conformational restriction design of thiophene-biphenyl-DAPY HIV-1 non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;182 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhan P., Chen X., Li D., Fang Z., De Clercq E., Liu X. HIV-1 NNRTIs: structural diversity, pharmacophore similarity, and implications for drug design. Med Res Rev. 2013;33(Suppl 1):E1–E72. doi: 10.1002/med.20241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhan P., Liu X., Li Z., Pannecouque C., De Clercq E. Design strategies of novel NNRTIs to overcome drug resistance. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:3903–3917. doi: 10.2174/092986709789178019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhuang C., Pannecouque C., De Clercq E., Chen F. Development of non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs): our past twenty years. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:961–978. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sang Y., Han S., Pannecouque C., De Clercq E., Zhuang C., Chen F. Ligand-based design of nondimethylphenyl-diarylpyrimidines with improved metabolic stability, safety, and oral pharmacokinetic profiles. J Med Chem. 2019;62:11430–11436. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin K., Yin H., De Clercq E., Pannecouque C., Meng G., Chen F. Discovery of biphenyl-substituted diarylpyrimidines as non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors with high potency against wild-type and mutant HIV-1. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;145:726–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding L., Pannecouque C., De Clercq E., Zhuang C., Chen F.E. Improving druggability of novel diarylpyrimidine NNRTIs by a fragment-based replacement strategy: from biphenyl-DAPYs to heteroaromatic-biphenyl-DAPYs. J Med Chem. 2021;64:10297–10311. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding L., Pannecouque C., De Clercq E., Zhuang C., Chen F.E. Discovery of novel pyridine-dimethyl-phenyl-DAPY hybrids by molecular fusing of methyl-pyrimidine-DAPYs and difluoro-pyridinyl-DAPYs: improving the druggability toward high inhibitory activity, solubility, safety, and PK. J Med Chem. 2022;65:2122–2138. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding L., Pannecouque C., De Clercq E., Zhuang C., Chen F.E. Hydrophobic pocket occupation design of difluoro-biphenyl-diarylpyrimidines as non-nucleoside HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors: from N-alkylation to methyl hopping on the pyrimidine ring. J Med Chem. 2021;64:5067–5081. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sang Y., Pannecouque C., De Clercq E., Zhuang C., Chen F. Chemical space exploration of novel naphthyl-carboxamide-diarylpyrimidine derivatives with potent anti-HIV-1 activity. Bioorg Chem. 2021;111 doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.104905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deng Q., Zheng Q., Zuo B., Tu T. Robust NHC-palladacycles-catalyzed Suzuki−Miyaura cross-coupling of amides via C‒N activation. Green Synth Catal. 2020;1:75–78. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gong B., Zhu H., Liu Y., Li Q., Yang L., Wu G., et al. Palladium-catalyzed sulfonylative coupling of benzyl(allyl) carbonates with arylsulfonyl hydrazides. Green Synth Catal. 2022;3:110–115. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin X., Zhao L.M., Wang S., Huang W.J., Zhang Y.X., Pannecouque C., et al. Structure-based discovery of novel NH2-biphenyl-diarylpyrimidines as potent non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors with significantly improved safety: from NH2-naphthyl-diarylpyrimidine to NH2-biphenyl-diarylpyrimidine. J Med Chem. 2022;65:8478–8492. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez V.E., Sanchez-Parra C., Serrano Villar S. Etravirine drug interactions. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2009;27(Suppl 2):27–31. doi: 10.1016/S0213-005X(09)73216-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garrido A., Lepailleur A., Mignani S.M., Dallemagne P., Rochais C. hERG toxicity assessment: useful guidelines for drug design. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;195 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalyaanamoorthy S., Barakat K.H. Development of safe drugs: the hERG challenge. Med Res Rev. 2018;38:525–555. doi: 10.1002/med.21445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garvey L., Winston A. Rilpivirine: a novel non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:1035–1041. doi: 10.1517/13543780903055056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.John J., Liang D. Oral liquid formulation of etravirine for enhanced bioavailability. J Bioequivalence Bioavailab. 2014;6:46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pannecouque C., Daelemans D., De Clercq E. Tetrazolium-based colorimetric assay for the detection of HIV replication inhibitors: revisited 20 years later. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:427–434. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Auwerx J., North T.W., Preston B.D., Klarmann G.J., De Clercq E., Balzarini J. Chimeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and feline immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptases: role of the subunits in resistance/sensitivity to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:400–406. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.2.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singer V.L., Jones L.J., Yue S.T., Haugland R.P. Characterization of PicoGreen reagent and development of a fluorescence-based solution assay for double-stranded DNA quantitation. Anal Biochem. 1997;249:228–238. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.