Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Fixed-ratio combinations of basal insulin (BI) and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) have greater simplicity of administration with expected improved adherence/persistence with therapy, but real-world data are lacking.

OBJECTIVE:

To compare medication persistence, adherence, and health care resource utilization (HRU) and costs for insulin glargine 100 U/mL and the GLP-1 RA lixisenatide (iGlarLixi) with newly initiated free-dose combinations of BI and GLP-1 RAs initiated simultaneously or sequentially.

METHODS:

This analysis used the US Optum Clinformatics (January 2017 to November 2019) database and included data from adults (aged ≥ 18 years) with type 2 diabetes and a glycated hemoglobin A1c (A1c) of 8% or more. Participants received iGlarLixi or free-dose combinations of BI and GLP-1 RAs prescribed simultaneously or subsequently. Participants were followed for 12 months. Cohorts were propensity score matched on baseline characteristics. The primary outcome was persistence (days on treatment without discontinuation). Secondary outcomes were adherence (proportion of days covered), change in A1c, and all-cause and diabetes-related health care resource utilization and costs. Subgroup analyses were performed for individuals with A1c levels of 9% or more.

RESULTS:

After propensity score matching, there were 1,357 patients in each group; groups were well balanced. In the free-dose combination group, 65.6% started on BI, then added GLP-1 RAs; 28.5% started on GLP-1 RAs, then added BI; and 5.9% started on GLP-1 RAs and BI on the same day. In the subgroup with a baseline of A1c levels of 9% or more, 952 (iGlarLixi) and 932 (free-dose combination) participants were included. A significantly higher proportion of participants in the overall population who received iGlarLixi vs free-dose combinations were persistent (44.8% vs 36.3% [hazard ratio = 1.22, 95% CI = 1.11-1.35, P < 0.001]; the median [Q1, Q3] number of persistent days was 150 [63, 360] vs 120 [60, 310]) and adherent to therapy (41.3% vs 18.7%, [odds ratio = 3.06, 95% CI = 2.57-3.65; P < 0.001]). Results for persistence in the subpopulation of participants with HbA1c levels of 9% or more were similar. Reductions in A1c from baseline were similar between iGlarLixi and the free-dose combination group (overall population: −1.2% vs −1.3%; P = 0.1913), but the number of participants in the database with follow-up A1c data was low. All-cause and diabetes-related pharmacy visits and total medication and diabetes medication pharmacy claims costs were significantly lower (all P < 0.001) for those receiving iGlarLixi vs free-dose combinations in both populations.

CONCLUSIONS:

In adults with type 2 diabetes, iGlarLixi was associated with longer persistence by approximately 30 days, improved adherence, and reductions in outpatient and pharmacy visits and in pharmacy costs.

Plain language summary

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and basal insulin are types of treatment for people with type 2 diabetes. These treatments are injected under the skin. In this study, researchers wanted to see if there was a difference to receiving both treatments in the same injection (insulin glargine 100 U/mL and the GLP-1 RA lixisenatide [iGlarLixi]) or as separate injections. People who took iGlarLixi were more likely to continue treatment and take it as instructed. They also visited the pharmacy less often, resulting in lower pharmacy-related costs.

Implications for managed care pharmacy

This real-world study examined data from individuals with type 2 diabetes receiving either the fixed-ratio combination therapy iGlarLixi or newly initiated free-dose combinations of basal insulin and GLP-1 RA either simultaneously or sequentially. iGlarLixi was associated with significantly greater treatment persistence and adherence and fewer all-cause and diabetes-related pharmacy visits. Participants receiving iGlarLixi also had lower total medication and diabetes medication pharmacy claims costs, resulting in netneutral total health care costs.

Diabetes (both type 1 and type 2) represents a major health burden, affecting more than 10% of the American population (approximately 34 million people, of which 90%-95% have type 2 diabetes [T2D]).1 Health care costs are 2.3 times greater for Americans with diabetes (type 1 and type 2 combined) compared with those without diabetes, with $1 of every $7 spent on treating diabetes and its complications.2 Data from 2017 showed this represented an annual burden of $327 billion, of which $237 billion is spent on direct medical costs.2 As such, treating health care providers often need to consider overall value, including efficacy, safety, ease of use, and cost when determining choice of therapy.

T2D is a progressive, multifactorial disease with several pathophysiologic abnormalities, often requiring complex combination therapy to achieve and maintain glycemic control.3 Additionally, the progressive decline in pancreatic β-cell function leads to insulin deficiency and the need for treatment advancement.4

A considerable proportion of people with T2D need injectable agents such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) (30%-60% of people with T2D qualify for a GLP-1 RA; however, only 1%-10% receive them5) and/or basal insulin (BI) (approximately 26% of people with T2D in the United States use any type of insulin6) to manage their blood glucose. However, advancing therapy to an injectable option is often delayed, as reflected in real-world data reporting that initiation of a GLP-1 RA or BI in adults with suboptimally controlled T2D occurred at glycated hemoglobin A1c (A1c) values between 8.8% and 9.5%, respectively, in the United States, and 9.6% and 10.3%, respectively, in the United Kingdom.7 The same study showed that of those with a baseline A1c level of 9% or more, only 25% achieved control with a single injectable agent added to existing oral therapy (participants included were on ≥ 1 oral antidiabetic during the 180-day baseline period).7 Therefore, in those with A1c levels of 9% or more, both a simultaneous treatment approach and optimal persistence and adherence to therapy are needed to achieve better glycemic control. Unfortunately, complex medication regimens increase treatment burden for the individual with diabetes and increase the risk for suboptimal treatment adherence and persistence.

Other reported barriers to the use of injectable therapies include injection anxiety, concerns about insulin therapy,8-10 and fear of hypoglycemia, all of which can drive poor adherence and are often reported as reasons for missed, mistimed, or reduced insulin doses.9,11 There is an inverse relationship between the number of injections prescribed and treatment adherence or persistence, with once-daily regimens being associated with improvements in adherence and persistence compared with regimens requiring more than 1 injection per day.12,13

For people with T2D who need injectable therapy, a GLP-1 RA with demonstrated cardiovascular disease benefits is currently recommended as the first choice, with advancing therapy to include BI in those whose A1c remains above target.14 For individuals who are receiving GLP-1 RA therapy and need to intensify their therapy to include a BI, as they are above their target A1c, the American Diabetes Association Standards of Care recommends considering the use of a fixed-ratio combination (FRC) product.14 The American Diabetes Association standards also suggest that, in patients on BI therapy, the combination of BI therapy with a GLP-1 RA improves both efficacy and durability compared with BI alone. FRCs of BI and GLP-1 RAs (such as insulin glargine 100 U/mL and the GLP-1 RA lixisenatide [iGlarLixi] and insulin degludec 100 U/mL and liraglutide) have greater simplicity of administration than separate administration of their components.15 Although it is reasonable to assume that simplification of treatment would lead to improved adherence to and persistence with therapy, these outcomes cannot be measured in randomized controlled trials, and real-world data are lacking.

This retrospective, observational study compared persistence, treatment adherence, health care resource utilization (HRU), and costs for initiation of iGlarLixi vs the free-dose combinations of BI and GLP-1 RA, initiated simultaneously or sequentially.

Methods

POPULATION

This analysis used the US Optum Clinformatics database, a large electronic medical records database that provides deidentified patient-level data, including medical claims, pharmacy claims, laboratory test results, inpatient confinement, and provider data.16 Data were included from adults (aged ≥ 18 years) with a diagnosis of T2D using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes between January 1, 2017, and November 30, 2019, inclusive. Eligible participants had continuous medical and prescription drug coverage for the 6 months before the index date (baseline period) and at least 1 valid A1c value (between 8.0% and 15.0%) during the baseline period. Participants were excluded if they had a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes, were pregnant, or had gestational diabetes or polycystic ovarian syndrome during the study period. They were also excluded if they had any bolus or premix claims during the baseline period or on the index date.

To be included in the analysis, participants had to have at least 1 claim for oral antidiabetics drugs, BI, or GLP-1 RA during the baseline period. Participants were excluded from the iGlarLixi group if they had any claim for an FRC (iGlarLixi or insulin degludec 100 U/mL and liraglutide) therapy or any claims for 2 separate injectables (BI and GLP-1 RA) during the baseline period. Participants were excluded from the free-dose combination group if they had any claim for an FRC or any claims for 2 separate injectables (BI and GLP-1 RA) during the baseline period. The index date was the date of the first iGlarLixi claim for those in the iGlarLixi group. For the free-dose combination group, the index date was the date of any claim for simultaneous BI and GLP-1 RA or the date of claim for the sequential addition of the second injectable (BI or GLP-1 RA). An overlap between GLP-1 RA and BI claims of at least 14 days from the index date was required for inclusion.

Participants were propensity score matched using a greedy nearest neighbor matching algorithm. At first, a “caliper” (a measure of the required closeness of the match, defined based on a proportion of the SD of the logit of the propensity score) was identified. The algorithm then selected a participant treated with iGlarLixi and a matched participant treated with a free combination of BI and GLP-1 RA, whose propensity score was closest to that of the iGlarLixi participant within the caliper distance of each other. Matches were chosen for each iGlarLixi participant 1 at a time. Once a match was made, patients were not reconsidered for matching.

STUDY OUTCOMES

The primary outcome was treatment persistence, calculated as the number of days of continuous therapy from the point of initiation until the end of 12 months of follow-up.17 A maximum gap of 45 days was allowed between fills, which was similarly applied for 30-, 60-, or 90-day refills. Dates of early refills were adjusted to the day after finishing the supply from the previous fill. Treatment was considered to have been discontinued if the gap between the run-out date of the previous fill and the next fill was more than 45 days. A sensitivity analysis was performed using a permissible gap of 60 days.

Secondary outcome measures were treatment adherence, change from baseline in A1c, HRU, and health care costs. Treatment adherence was defined as the proportion of days covered (total days supplied on the claim divided by the number of days in refill interval, assuming all medications were consumed as prescribed) using a cutoff of 80% or more to define adherence and less than 80% for poor adherence. The same rule was applied separately for each prescription of BI or GLP-1 RA in the free-dose combination arm. Medication adherence was modeled using logistic regression. Change in A1c was calculated between the A1c measurement at baseline and 12 months after the index date. For inclusion in the A1c analysis, values were required at both baseline and 12 months. HRU was assessed during the follow-up period and included hospital admissions, emergency department (ED) visits, outpatient visits, and pharmacy visits. All-cause and diabetes-related hospitalization, ED, outpatient, medical claims, pharmacy claims, and total health care costs during the follow-up period were calculated.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

For treatment persistence, a Cox proportional hazards model was used to compare the risk of treatment discontinuation between the treatment groups, whereas Kaplan–Meier analyses were performed to compare the time to discontinuation. The percentage of participants with treatment persistence throughout the 12-month follow-up period was calculated along with the median duration of persistence in days. For treatment adherence, statistical differences in the rates of proportion of days covered at 80% or more were assessed using logistic regression. Crude incidence rates for hospitalizations and ED visits were reported as mean number of events and event rates (number of events per 100 person-years [P100PY]). Event rates for outpatient and pharmacy visits (number of unique days when a prescription was filled) were reported per person per year (PPPY). Health care costs were reported as US dollar costs PPPY (adjusted for inflation up to 2020). All-cause and diabetes-related HRU and costs were estimated with a generalized linear regression model with Poisson and gamma distribution during the follow-up period.18 Statistical differences in A1c change was assessed using generalized linear regression model.

Results

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

From an initial sample of 4,448,622 people with T2D diagnosed between January 1, 2017, and November 30, 2019, a total of 1,357 people who initiated iGlarLixi and 4,482 who initiated a free-dose combination of a GLP-1 RA and BI were identified as eligible for propensity score matching (PSM) (Supplementary Table 1 (129.2KB, pdf) , available in online article). After PSM, there were 1,357 participants in each group; each group was well balanced, with a mean age of 62.1 years, 52% female, and a mean A1c closest to the index date (taken during the baseline period) of 10.0% (Table 1). In the free-dose combination group, 890 (65.6%) participants started on BI then sequentially added a GLP-1 RA, 387 (28.5%) participants started on GLP-1 RA and then sequentially added BI, and 80 (5.9%) started GLP-1 RA and BI on the same day. The most common GLP-1 RA prescribed was dulaglutide (weekly, range: 44.4%-50.2% for each free-dose combination scenario) followed by liraglutide (daily, range: 30.7%-39.5%).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Propensity Score–Matched Population

| Baseline patient characteristic | Propensity score-matched population | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| iGlarLixi cohort n = 1,357 | Free-combo cohort n = 1,357 | Standardized mean difference | |

| Age group, n (%) | |||

| 18-49 years | 193 (14.2) | 189 (13.9) | 0.0443 |

| 50-64 years | 547 (40.3) | 535 (39.4) | |

| 65-74 years | 425 (31.3) | 452 (33.3) | |

| ≥ 75 years | 192 (14.1) | 181 (13.3) | |

| Age, years | |||

| Mean (SD) | 62.1 (11.4) | 62.2 (11.3) | 0.0058 |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 63 (17.00) | 63.0 (15.00) | |

| Minimum, maximum | 26, 88 | 24, 90 | |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 651 (48.0) | 650 (47.9) | 0.0015 |

| Female | 706 (52.0) | 707 (52.1) | |

| Unknown | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | |

| Race and ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Asian | 50 (3.7) | 40 (2.9) | 0.0424 |

| African American | 191 (14.1) | 190 (14.0) | |

| Hispanic | 353 (26.0) | 352 (25.9) | |

| White | 564 (41.6) | 571 (42.1) | |

| Other/unknown | 199 (14.7) | 204 (15.0) | |

| Health plan type, n (%) | |||

| Commercial | 705 (52.0) | 683 (50.3) | 0.0324 |

| Medicare | 652 (48.0) | 674 (49.7) | |

| Region, n (%) | |||

| Midwest | 81 (6.0) | 73 (5.4) | 0.0291 |

| Northeast | 70 (5.2) | 72 (5.3) | |

| South | 917 (67.6) | 926 (68.2) | |

| West | 264 (19.5) | 263 (19.4) | |

| Unknown | 25 (1.8) | 23 (1.7) | |

| Common comorbidities and diabetic complications of interest, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 1,128 (83.1) | 1,120 (82.5) | 0.0156 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1,126 (83.0) | 1,127 (83.1) | 0.0020 |

| Neuropathy | 398 (29.3) | 383 (28.2) | 0.0244 |

| Nephropathy | 115 (8.5) | 131 (9.7) | 0.0411 |

| Retinopathy | 181 (13.3) | 182 (13.4) | 0.0022 |

| Obesity | 532 (39.2) | 521 (38.4) | 0.0166 |

| Depression | 204 (15.0) | 206 (15.2) | 0.0041 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 286 (21.1) | 283 (20.9) | 0.0054 |

| Hypoglycemia | 53 (3.9) | 44 (3.2) | 0.0357 |

| A1c closest to index treatment initiation, n (%) | |||

| ≥ 8 and < 9 | 405 (29.8) | 425 (31.3) | 0.0329 |

| ≥ 9 and < 11 | 623 (45.9) | 614 (45.2) | |

| ≥ 11 | 329 (24.2) | 318 (23.4) | |

| A1c closest to index treatment initiation | |||

| Mean (SD) | 10.0 (1.5) | 9.9 (1.5) | 0.0319 |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 9.6 (2.10) | 9.6 (2.10) | |

| Minimum, maximum | 8, 15 | 8, 15 | |

| SH event rate per 100 person-years during baseline period | 2.2 | 2.5 | |

| SH incidence during baseline period, n (%) | 13 (1.0) | 15 (1.1) | 0.0146 |

| Number of OADs in baseline period, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 134 (9.9) | 139 (10.2) | 0.0273 |

| 1 | 536 (39.5) | 538 (39.6) | |

| 2 | 453 (33.4) | 459 (33.8) | |

| ≥ 3 | 234 (17.2) | 221 (16.3) | |

| Use of OADs medications in baseline period, n (%) | |||

| Metformin | 818 (60.3) | 826 (60.9) | 0.0121 |

| Sulfonylureas | 489 (36.0) | 482 (35.5) | 0.0108 |

| DPP-4i | 280 (20.6) | 283 (20.9) | 0.0055 |

| SGLT-2 inhibitors | 337 (24.8) | 339 (25.0) | 0.0034 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 149 (11.0) | 142 (10.5) | 0.0167 |

| α-glucosidase inhibitors | 9 (0.7) | 9 (0.7) | 0.0000 |

| Meglitinides | 21 (1.5) | 18 (1.3) | 0.0186 |

| SGLT-2 combo | 6 (0.4) | 2 (0.1) | 0.0544 |

| Biguanides combination | 93 (6.9) | 81 (6.0) | 0.0361 |

| Health care utilization, n (%) | |||

| ≥ 1 office visit | 1,274 (93.9) | 1,267 (93.4) | 0.0211 |

| ≥ 1 office visit with a diabetologist or endocrinologist | 320 (23.6) | 322 (23.7) | 0.0035 |

| ≥ 1 hospitalization | 78 (5.7) | 79 (5.8) | 0.0032 |

| ≥ 1 ED visit | 231 (17.0) | 237 (17.5) | 0.0117 |

DPP-4i = dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; ED = emergency department; A1c = glycated hemoglobin A1c; iGlarLixi = insulin glargine 100 U/mL and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide; OAD = oral antidiabetic drug; SH = severe hypoglycemia; SGLT-2 = sodium-glucose cotransporter-2.

For the subset analyses of participants with an A1c of 9% or more at baseline, a subgroup of the overall population after PSM was used (952 participants in the iGlarLixi group and 932 in the free-dose combination).

PRIMARY OUTCOME: TREATMENT PERSISTENCE

During the 12-month follow-up period, a significantly higher proportion of the overall population of participants who received iGlarLixi vs free-dose combinations were persistent with therapy (44.8% vs 36.3% [hazard ratio = 1.22, 95% CI = 1.11-1.35; P < 0.001]) (Figure 1). The median (Q1, Q3) number of persistent days was 150 (63, 360) for iGlarLixi and 120 (60, 310) for free-dose combinations. The sensitivity analysis (using a < 60-day gap) supported the main findings (hazard ratio = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.14-1.41; P < 0.001).

FIGURE 1.

Persistence and Adherence in the Overall Population and in Those With a Baseline A1c of 9% or More

In the population with a baseline A1c of 9% or more, a significantly higher proportion of participants who received iGlarLixi vs free-dose combination were persistent with therapy (43.5% vs 35.0%; [hazard ratio = 1.25, 95% CI = 1.11-1.35; P < 0.001]) (Figure 1). The median (Q1, Q3) number of persistent days was 137 (60, 360) for iGlarLixi and 111 (60, 294) for free-dose combinations.

SECONDARY OUTCOMES

A significantly higher proportion of participants who received iGlarLixi vs free-dose combinations were adherent to therapy (41.3% vs 18.7% [odds ratio = 3.06, 95% CI = 2.57-3.65; P < 0.001]) (Figure 1). The median number of adherent days was 200 for iGlarLixi and 99 for free-dose combinations. Similar results were observed in the subpopulation of patients with an A1c of 9% or more (40.8% vs 19.4% [odds ratio = 2.85, 95% CI = 2.32-3.52; P < 0.001]) (Figure 1).

Reductions in A1c from baseline were similar between iGlarLixi and the free-dose combination group both for the overall population (−1.2% vs −1.3%; P = 0.1913) and for the population with a baseline A1c of 9% or more (−1.6 vs −1.8; P = 0.1674). Follow-up data were available for only 36% of the individuals enrolled in the Optum Clinformatics database and for only 24% of the subset of participants with a baseline A1c of 9% or more.

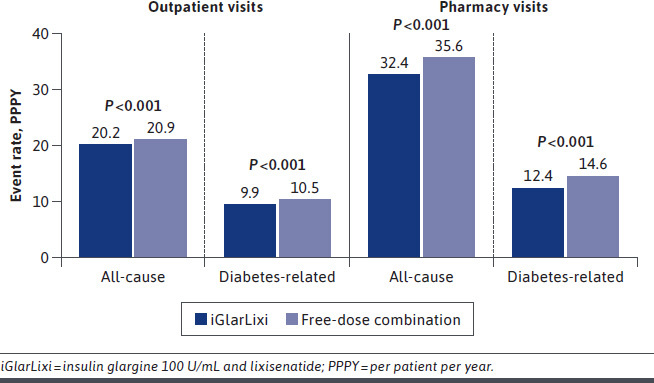

In the overall population, hospitalization event rates were comparable between the iGlarLixi and free-dose combination groups: all-cause (20.7 vs 20.0 P100PY; P = 0.706) and diabetes-related (19.5 vs 19.0 P100PY; P = 0.773). Event rates for ED visits for all-cause (56.5 vs 57.5 P100PY; P = 0.756) and diabetes-related (42.5 vs 42.9 P100PY; P = 0.897) were also comparable between iGlarLixi and free-dose combination groups. Statistically significant lower event rates for all-cause (20.2 vs 20.9 PPPY; P < 0.001) and diabetes-related (9.9 vs 10.5 PPPY; P < 0.001) outpatient visits were observed in the iGlarLixi group, compared with the free-dose combination group (Figure 2), although the differences were minimal. Similarly, statistically significant lower event rates for all-cause (32.4 vs 35.6 PPPY; P < 0.001) and diabetes-related (12.4 vs 14.6 PPPY; P < 0.001) pharmacy visits were observed in the iGlarLixi group vs the free-dose combination group (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Health Care Resource Utilization in the Overall Population

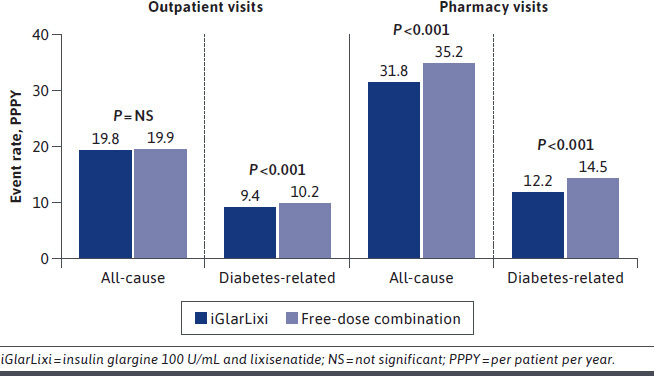

For the subpopulation with a baseline A1c of 9% or more, event rates for hospitalizations (all-cause [22.5 vs 20.5 P100PY; P = 0.429] and diabetes-related [21.1 vs 19.6 P100PY; P = 0.475]) and ED visits (all-cause [61.5 vs 61.2 P100PY; P = 0.941] and diabetes-related [46.0 vs 44.2 P100PY; P = 0.592]) were comparable between the iGlarLixi and free-dose combination groups, respectively (Figure 3). Statistically significant lower event rates for diabetes-related outpatient visits (9.4 vs 10.2 PPPY; P < 0.001) and all-cause (31.8 vs 35.2 PPPY; P < 0.001) and diabetes-related (12.2 vs 14.5 PPPY; P < 0.001) pharmacy visits were observed in the iGlarLixi group compared with the free-dose combination group (Figure 2). The difference in event rates for all-cause outpatient visits (19.8 vs 19.9 PPPY; P = 0.85) was not statistically different between the iGlarLixi and free-dose combination groups.

FIGURE 3.

Health Care Resource Utilization in Those With a Baseline Glycated Hemoglobin A1c of 9% or More

In the overall population, costs for all-cause and diabetes-related hospitalizations and ED visits, as well as outpatient, medical claims, and total claims costs, were comparable, though generally numerically lower, between the iGlarLixi and the free-dose combination groups (Table 2). Similar results were observed in those with a baseline A1c of 9% or more. All-cause and diabetes-related pharmacy claims costs, however, were significantly lower (all P < 0.001) for those receiving iGlarLixi than for those receiving free-dose combinations, both in the overall population and in those with a baseline A1c of 9% or more (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Health Care Claims Costs

| Costs | Overall population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause costs | Diabetes-related costs | |||||

| iGlarLixi n = 1,357 | Free-dose combination n = 1,357 | P value | iGlarLixi n = 1,357 | Free-dose combination n = 1,357 | P value | |

| Hospitalization | 6,150.51 | 5,791.90 | 0.781 | 5,470.85 | 5,560.34 | 0.890 |

| ED | 838.08 | 896.77 | 0.486 | 719.34 | 746.26 | 0.708 |

| Outpatient | 6,767.33 | 6,814.97 | 0.856 | 3,841.55 | 4,417.42 | 0.188 |

| Medical claims | 13,755.92 | 13,503.64 | 0.930 | 10,031.74 | 10,724.02 | 0.513 |

| Pharmacy claims | 4,239.27 | 5,865.43 | < 0.001 | 2,566.56 | 4,119.61 | < 0.001 |

| Total claims | 17,995.19 | 19,369.07 | 0.271 | 12,598.30 | 14,843.62 | 0.050 |

| Costs | Baseline ≥ 9% | |||||

| All-cause costs | Diabetes-related costs | |||||

| iGlarLixi n = 952 | Free-dose combination n = 932 | P value | iGlarLixi n = 952 | Free-dose combination n = 932 | P value | |

| Hospitalization | 6,636.71 | 6,031.29 | 0.671 | 5,731.47 | 5,904.96 | 0.877 |

| ED | 896.26 | 907.59 | 0.899 | 758.36 | 729.09 | 0.815 |

| Outpatient | 6,604.06 | 6,698.54 | 0.862 | 3,722.40 | 4,562.34 | 0.138 |

| Medical claims | 14,137.04 | 13,637.42 | 0.790 | 10,212.23 | 11,196.39 | 0.490 |

| Pharmacy claims | 4,189.66 | 5,693.90 | < 0.001 | 2,529.76 | 3,998.52 | < 0.001 |

| Total claims | 18,326.69 | 19,331.32 | 0.521 | 12,741.99 | 15,194.91 | 0.092 |

Costs are per person per year in US dollars.

ED = emergency department; iGlarLixi = insulin glargine 100 U/mL and lixisenatide.

Discussion

The results of this retrospective, real-world observational study in people with T2D show that compared with free-dose combinations of BI and a GLP-1 RA, the use of iGlarLixi was associated with statistically significant improvements in treatment persistence and adherence, reductions in pharmacy visits, and reductions in pharmacy costs. There was no difference in change in A1c between the use of iGlarLixi or freedose combinations; however, only a small number of patients had follow-up data for A1c available. These results were also observed in the cohort of patients with a baseline A1c of 9% or more.

Overall rates of persistence and adherence in the current study to both iGlarLixi and free-dose combinations were within the ranges for injectable agents reported in a systematic review of adherence, persistence, and health outcomes of injectable antihyperglycemics.19 That review showed that estimates of persistence for GLP-1 RAs were between 17% and 86%, and estimated 1-year persistence for insulin therapy ranged between 21% and 66%.19 Reported rates of adherence for insulin range between 30% and 86%.9 In a recent study comparing persistence and adherence to therapy between the weekly injectable GLP-1 RAs dulaglutide and semaglutide, persistence (no gap in therapy for ≥ 45 days) of 55.5% vs 45.3% and adherence (proportion of days covered ≥ 80%) of 54.4 vs 43.3 were observed, respectively.20 Persistence and adherence measures to iGlarLixi in the current study were similar to those observed with semaglutide. Of note, in the free-dose combination group, approximately 45%-50% of people included were taking dulaglutide, further adding relevance to the diminished persistence and adherence in the free-dose combinations of GLP-1 RAs and BI observed in our study. However, comparisons between studies are difficult to make because of differences in study populations and methods used to measure persistence or adherence. Furthermore, when using claims data, because individualized dosing information is often unavailable, treatment persistence and adherence can only be estimated.

In the current study, iGlarLixi was associated with significantly greater persistence and adherence to therapy than free-dose combinations of BI and GLP-1 RAs. It is known that as the complexity of therapeutic regimens increases, so does the burden on the individual needing the therapy. This increased burden can be driven by different factors, such as number of prescribed agents, dosing frequency and titration, side effects, medication costs, and concerns over the use of injectables.9 In particular, fear of insulin therapy and anxiety over injections have been reported as barriers to persistence and poor adherence.8-10 A US study demonstrated that persistence was higher in people initiating insulin with once-daily insulin glargine compared with a twice-daily, premixed insulin analog (55.9% vs 45.4%, respectively; P < 0.0001).12 A study of people with T2D in Scotland has also shown that adherence to treatment is associated with the number of injections a day, with those using a single daily injection having higher adherence than those receiving 4 injections a day (78.3% vs 60.8%, respectively; P < 0.0001).13 Taken together with the results of the current study, this would suggest that the single injection required for iGlarLixi offers a more simplified administration, compared with the 2 separate injections needed for a free-dose combination of BI and a GLP-1 RA, and could be related to the higher persistence and adherence observed in this study with iGlarLixi. However, it is important to note that in the free-dose combination group, between 44.4% and 50.2% of participants were prescribed the weekly GLP-1 RA dulaglutide. These participants would require 1 injection of insulin per day, except for the 1 day a week with the added injection for the additional GLP-1 RA.

Another factor related to poor persistence is fear of hypoglycemia.9 Compared with insulin glargine alone, treatment with iGlarLixi can achieve greater glycemic control with a comparable risk of hypoglycemia.21,22 In addition, iGlarLixi mitigates the gastrointestinal effects associated with treatment of lixisenatide alone, which may be because lixisenatide is titrated more slowly when administered as iGlarLixi than when administered alone.23 Taken together, improved persistence and adherence observed with iGlarLixi in this study may in part be driven by these factors. However, as data for hypoglycemic or adverse event rates are not included in this analysis, no firm conclusion can be made.

Both in the overall population and in those with baseline A1c of 9% or more, patients receiving iGlarLixi required fewer all-cause or diabetes-related outpatient or pharmacy visits, compared with those receiving free-dose combinations. Additionally, all-cause and diabetes-related pharmacy claims costs were lower for those receiving iGlarLixi vs free-dose combinations of BI and GLP-1 RA. Single prescriptions for iGlarLixi offer convenience compared with separate prescriptions, possibly dispensed on separate days, for BI and GLP-1 RA.

In the current study, reductions in A1c were similar between those receiving iGlarLixi or free-dose combination therapies. It is important to note that this comparable efficacy is achieved at a lower pharmacy cost. Unfortunately, A1c values at 12 months of follow-up were available for only 36% of the individuals enrolled in the Optum Clinformatics database and for only 24% of the subset of participants with a baseline A1c of 9% or more; consequently, no definitive conclusions on efficacy can be drawn from this small sample, and this may not allow for any translatable benefit to glycemic control from higher persistence or adherence to be observed in this study. A previous real-world evidence study using data from the regional US electronic medical records database Research Action for Health Network demonstrated that simultaneous initiation of BI and GLP-1 RA achieved glycemic control (A1c < 7% at 12 months) more effectively than the sequential initiation of BI with GLP-1 RA added beyond 90 days (33.4% of 109 participants vs 20.9% of 459 participants, respectively; P = 0.0186).24

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

Strengths of this analysis are that the Optum claims database allows the use of a large population with long-term follow-up and breadth of coverage, which provided considerable statistical power. However, caution is required when interpreting results of comparative observational studies, as biases may be present because of the lack of randomization. In the current study, the use of PSM should have mitigated some of the confounding factors. Data were collected from a clinical practice database, which was not specifically designed for research purposes. As a result, data that would often be useful for analysis may have been missing, erroneous, or misclassified.25 Laboratory results are often not available for all people included in the Optum database, as exhibited in this study, in which 12-month follow-up A1c values were available for only 36% of the individuals in the main analysis and for only 24% of the subset of participants with a baseline A1c of 9% or more. Individualized dosing data were not available; therefore, it is not possible to know how many days supply was included in each individual prescription. Furthermore, it is not possible to determine if medication was taken or titrated to the maximum effective dose, or how individualized A1c targets may have affected glycemic outcomes. Additionally, it is not possible to know the reasons for therapy discontinuation or medication switches. The database is only current to 2019, and treatment patterns may have changed. Finally, the generalizability of the study may be limited to the populations represented in the Optum Clinformatics database.

Conclusions

Compared with those who received free-dose combinations of BI and a GLP-1 RA, participants receiving iGlarLixi had 18% less risk of discontinuing therapy, a median of 30 days of longer persistence with therapy, significantly lower all-cause and diabetes-related pharmacy visits, significantly lower total and diabetes medication pharmacy claims costs, and were 3 times more likely to be adherent to therapy. Findings for the subpopulation of participants with a baseline A1c of 9% or more were similar to those for the overall cohort. There was no difference between iGlarLixi and other treatments in reduction in A1c; however, the low numbers of participants with follow-up data for A1c measurements (64% and 76% with no follow-up data for the overall population and those with a baseline A1c of ≥ 9%, respectively) made any meaningful comparison between groups difficult. The findings of this study suggest that people with T2D who require both a GLP-1 RA and BI would benefit from a single injection offered by an FRC drug, such as iGlarLixi, because of a reduced need to visit the pharmacy, which tends to result in lower costs. These benefits translated to better persistence and adherence to therapy in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Quentin Pilard (Quinten Health, France) and Kahina Lounaci (Quinten Health, France) for providing analytical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020. Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. 2020. Accessed September 21, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf

- 2.American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the US in 2017. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(5):917-28. doi: 10.2337/dci18-0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeFronzo RA, Eldor R, Abdul-Ghani M. Pathophysiologic approach to therapy in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36 (Suppl 2):S127-38. doi: 10.2337/dcS13-2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wysham C, Shubrook J. Beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes: Mechanisms, markers, and clinical implications. Postgrad Med. 2020;132(8):676-86. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2020.1771047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nauck MA, Quast DR, Wefers J, Meier JJ. GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes – state-of-the-art. Mol Metab. 2021;46:101102. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang M, Wang D, Coresh J, Selvin E. Trends in diabetes treatment and control in US adults, 1999–2018. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(23):2219-28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa2032271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng XV, McCrimmon RJ, Shepherd L, et al. Glycemic control following GLP-1 RA or basal insulin initiation in real-world practice: A retrospective, observational, longitudinal cohort study. Diabetes Ther. 2020;11(11):2629-45. doi: 10.1007/s13300-020-00905-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies MJ, Gagliardino JJ, Gray LJ, Khunti K, Mohan V, Hughes R. Real-world factors affecting adherence to insulin therapy in patients with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Diabet Med. 2013;30(5):512-24. doi: 10.1111/dme.12128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerci B, Chanan N, Kaur S, Jasso-Mosqueda JG, Lew E. Lack of treatment persistence and treatment nonadherence as barriers to glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2019;10(2):437-49. doi: 10.1007/s13300-019-0590-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicolucci A, Kovacs Burns K, Holt RI, et al. Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs second study (DAWN2TM): Cross-national benchmarking of diabetes-related psychosocial outcomes for people with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2013;30(7): 767-77. doi: 10.1111/dme.12245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ampudia-Blasco FJ, Galán M, Brod M. A cross-sectional survey among patients and prescribers on insulin dosing irregularities and impact of mild (self-treated) hypoglycemia episodes in Spanish patients with type 2 diabetes as compared to other European patients. Endocrinol Nutr. 2014;61(8):426-33. doi: 10.1016/j.endonu.2014.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baser O, Tangirala K, Wei W, Xie L. Real-world outcomes of initiating insulin glargine-based treatment versus premixed analog insulins among US patients with type 2 diabetes failing oral antidiabetic drugs. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:497-505. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S49279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donnelly LA, Morris AD, Evans JMM; DARTS/MEMO collaboration. Adherence to insulin and its association with glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. QJM. 2007;100(6):345-50. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(Suppl 1):S1-2. doi: 10.2337/dc22-Sint [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skolnik N, Hinnen D, Kiriakov Y, Magwire ML, White JR, Jr. Initiating titratable fixed-ratio combinations of basal insulin analogs and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists: What you need to know. Clin Diabetes. 2018;36(2):174-82. doi: 10.2337/cd17-0048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Optum Inc. Clinformatics for managed markets. Accessed March 15, 2022. https://www.optum.com/business/solutions/life-sciences/real-world-data/managed-markets.html

- 17.Mody R, Huang Q, Yu M, et al. Adherence, persistence, glycaemic control and costs among patients with type 2 diabetes initiating dulaglutide compared with liraglutide or exenatide once weekly at 12-month follow-up in a real-world setting in the United States. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21(4):920-9. doi: 10.1111/dom.13603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olsen M, Schafer J. A two-part random-effects model for semicontinuous longitudinal data. J Am Stat Assoc. 2001;96 (454):730-45. doi: 10.1198/016214501753168389 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamersky CM, Fridman M, Gamble CL, Iyer NN. Injectable antihyperglycemics: A systematic review and critical analysis of the literature on adherence, persistence, and health outcomes. Diabetes Ther. 2019;10(3):865-90. doi: 10.1007/s13300-019-0617-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mody R, Manjelievskaia J, Marchlewicz EH, et al. Greater adherence and persistence with injectable dulaglutide compared with injectable semaglutide at 1-year follow-up: Data from US clinical practice. Clin Ther. 2022;44(4):537-54. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2022.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aroda VR, Rosenstock J, Wysham C, et al. Efficacy and safety of LixiLan, a titratable fixed-ratio combination of insulin glargine plus lixisenatide in type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on basal insulin and metformin: The LixiLan-L randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(11):1972-80. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenstock J, Aronson R, Grunberger G, et al. Benefits of LixiLan, a titratable fixed-ratio combination of insulin glargine plus lixisenatide, versus insulin glargine and lixisenatide monocomponents in type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on oral agents: The LixiLan-O randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(11):2026-35. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hinnen D, Strong J. iGlarLixi: A new once-daily fixed-ratio combination of basal insulin glargine and lixisenatide for the management of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2018;31(2):145-54. doi: 10.2337/ds17-0014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng XV, Ayyagari R, Lubwama R, et al. Impact of simultaneous versus sequential initiation of basal insulin and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on HbA1c in type 2 diabetes: A retrospective observational study. Diabetes Ther. 2020;11(4):995-1005. doi: 10.1007/s13300-020-00783-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernandez-Boussard T, Monda KL, Crespo BC, Riskin D. Real world evidence in cardiovascular medicine: Ensuring data validity in electronic health record-based studies. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(11):1189-94. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]