Abstract

Purpose of Review

Proximal humerus fracture dislocations typically result from high-energy mechanisms and carry specific risks, technical challenges, and management considerations. It is vital for treating surgeons to understand the various indications, procedures, and complications involved with their treatment.

Recent Findings

While these injuries are relatively rare in comparison with other categories of proximal humerus fractures, fracture dislocations of the proximal humerus require treating surgeons to consider patient age, activity level, injury pattern, and occasionally intra-operative findings to select the ideal treatment strategy for each injury.

Summary

Proximal humerus fracture dislocations are complex injuries that require special considerations. This review summarizes recent literature regarding the evaluation and management of these injuries as well as the indications and surgical techniques for each treatment strategy. Thorough pre-operative patient evaluation and shared decision-making should be employed in all cases. While nonoperative management is uncommonly considered, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), hemiarthroplasty, and reverse total shoulder replacement are at the surgeon’s disposal, each with their own indications and complication profile.

Keywords: Fracture dislocation, Glenohumeral joint, Proximal humerus, Shoulder dislocation

Introduction

Proximal humerus fractures account for 4–10% of all fractures and present a wide range of fracture patterns and injury severity [1]. The incidence of proximal humerus fractures increases substantially with increasing age, with incidence surpassing 200 per 100,000 person-years in patients age 60 and over [2]. Additionally, women are 2.7 times more likely than men to experience these injuries [3]. A subset of proximal humerus fractures include fracture dislocations, which typically arise from higher energy mechanisms and carry specific risks, technical challenges, and management considerations. While these injuries are encountered less frequently, fracture dislocations of the proximal humerus represent complex injuries that require treating surgeons to consider both patient and injury factors to determine the ideal treatment.

Classification Schemes

Neer studies provide a widely used framework for characterization and evaluation of proximal humerus fractures [4]. The four “parts” described by Neer include the following: (1) the greater tuberosity, (2) the lesser tuberosity, (3) the surgical neck, and (4) the anatomic neck. In the setting of proximal humerus fractures, these four parts are represented and identifiable based on anatomic relationships. The greater tuberosity represents the insertion site for the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor tendons, commonly referred to as posterosuperior rotator cuff. The lesser tuberosity functions as the insertion site for the subscapularis tendon, which constitutes the anterior portion of the rotator cuff. Together, these muscles and their relevant insertion sites provide dynamic support of the shoulder joint. The intertubercular sulcus or groove, where the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii travels, provides a bony landmark that separates the greater and lesser tuberosities [5]. The surgical neck is located below the humeral head and typically represents the weakest region of bone in the proximal humerus. Lastly, the anatomic neck is the fused remnant of the proximal humeral epiphysis.

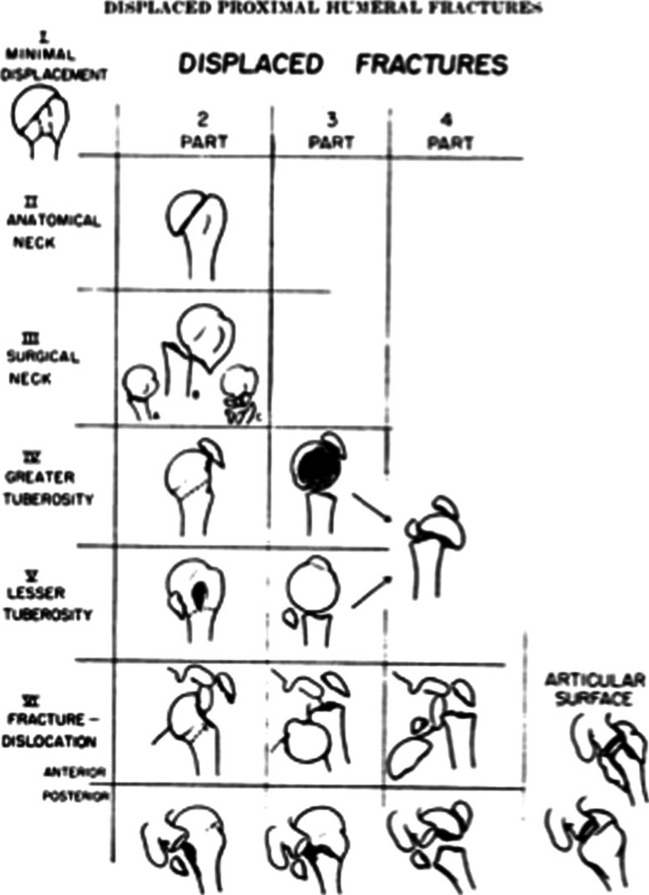

The Neer classification, which is displayed in Fig. 1, is based on the presence or absence of displacement of one or more of the four anatomical segments of the proximal humerus [4]. Displacement of a segment was arbitrarily defined as greater than 1 cm of fragment migration from its anatomic location or fragment angulation greater than 45°. Description of injuries utilizing the Neer classification can be carried out by describing the number of displaced segments or alternatively through the classification Groups I–VI initially described by Neer.

Fig. 1.

The Neer four-segment classification system for proximal humerus fractures. Reprinted with permission from Neer CS 2nd. Displaced proximal humeral fractures. I. Classification and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52:1077–1089

A “One-Part” injury describes any fracture pattern in which no part is displaced i.e. no segment is over a centimeter displaced or angulated greater than 45°. It should be noted that nondisplaced fracture lines involving multiple parts of the proximal humerus still constitute a “One-Part” fracture pattern under the classification set forth by Neer. A “Two-Part” injury signifies displacement of a single segment, which may include the anatomic neck, the surgical neck, the greater tuberosity, or the lesser tuberosity. Three- and Four-Part injuries represent displacement of additional proximal humerus segments and signify an increase in proximal humerus injury severity as well as proximal humeral blood supply disruption.

Neer Group VI defines fracture dislocations of the proximal humerus, which will be the focus of this review [4]. These injury patterns involve displacement of one or more of the four parts of the proximal humerus with concomitant glenohumeral joint dislocation. These groups of injuries encompass a wide array of proximal humerus fracture patterns in the setting of anterior or posterior glenohumeral dislocation, ranging from a greater tuberosity fracture (“Two-Part”) to a “Four-Part” fracture with articular split.

The Mayo-Fundación Jiménez Díaz (Mayo-FJD) classification for proximal humerus fractures similarly identifies fracture patterns via displacement criteria [6]. This classification system, which can be seen in Fig. 2, simplifies fracture patterns into three main groups and then further categorizes them into one of seven major patterns. The three main classifications described in the Mayo-FJD Classification system include (1) fractures where only the tuberosities are fractured, (2) fractures where the humeral head is severely compromised due to fracture dislocation, severe impaction, or head-splitting, and (3) fractures where the head is intact, not dislocated, but fractured at the anatomic or surgical neck.

Fig. 2.

Mayo-FJD classification system of proximal humerus fractures. Radiographs depict examples of the 7 major patterns of proximal humerus fractures as defined by the classification system, which include isolated tuberosity fracture (GT or LT), varus posteromedial (VPM), valgus impacted (VL), surgical neck (SN), head dislocation, head split, and head impression. Reprinted with permission from Foruria AM, Martinez-Catalan N, Pardos B, Larson D, Barlow J, Sanchez-Sotelo J. Classification of proximal humerus fractures according to pattern recognition is associated with high intraobserver and interobserver agreement. JSES International. 2022;6(4):563–568

Group 1 injuries, or fractures of the greater tuberosity or lesser tuberosity, can be an isolated injury or occur in the setting of an anterior or posterior dislocation, respectively. Tuberosity displacement is only assessed after reduction of the dislocation. Group 2 injuries represent fractures patterns with humeral head compromise or articular injury, including fractures with head dislocation, severe humeral head impaction, or head-split components. Group 3 injuries, or fractures of the anatomic or surgical neck, are further defined by their characteristic displacement deformity and referred to as varus posteromedial (VPM), valgus impacted (VL), or surgical neck (SN) fractures. These injuries can also be further subclassified by the presence or absence of fracture of one or both tuberosities.

Associated Injuries

Anterior fracture dislocations of the proximal humerus have been reported to confer increased risk of injury to the axillary neurovascular bundle as it courses from anterior to posterior at the inferior glenoid neck [7–9]. While axillary artery injuries remain rare overall, anterior shoulder dislocation increases the risk of axillary artery injuries from both undue tension and/or direct trauma [8]. Additionally, significant medialization of the humeral shaft into the anteroinferior glenoid neck as can often be seen in proximal humerus fracture dislocations is also a reported mechanism for axillary artery occlusion or laceration [7, 9]. Axillary artery injuries may not present with distal ischemia or loss of pulses as a result of compensatory collateral flow to the upper extremity.

Clinicians should be aware that proximal humerus fracture dislocations are also associated with an increased risk of associated axillary nerve injury, which can arise from either a traction-induced brachial plexopathy or direct axillary nerve trauma [8]. Axillary nerve injury may be masked by pain and limited physical exam at the time of presentation. Given the axillary nerve’s role in innervation of the teres minor and deltoid muscles, axillary nerve injury in the setting of a proximal humerus fracture carries significant clinical implications. As such, axillary nerve function should be evaluated prior to any surgical intervention, especially if reverse shoulder arthroplasty is a potential treatment option.

Evaluation and Management

Careful physical exam is required for all patients presenting with proximal humerus fractures. The clinician must inspect the area for open fracture and deformity and carry out a neurologic and vascular examination of the affected extremity. Loss of deltoid contour may increase suspicion of a fracture dislocation [9]. Neurologic examination of the axillary nerve may be challenging to assess at presentation, as patient pain and loss of function typically precludes motor examination of the deltoid or teres minor [8]. The deltoid musculature can be evaluated for subtle contractility if the patient is compliant and tolerant. Axillary nerve sensory innervation over the lateral shoulder, also referred to as the “regimental badge area,” can be assessed as a proxy for axillary nerve function. As discussed, vascular compromise must be a consideration even in the setting of intact distal pulses. Reduction in Doppler ultrasound signal with comparison to the contralateral limb or an expanding axillary mass should raise concern for axillary artery injury. [7]

Standard radiographic imaging should include Grashey (true AP), Neer (scapular Y), and axillary lateral views [9]. If an axillary view cannot be obtained to evaluate for glenohumeral dislocation secondary to patient discomfort, a Velpeau view can be utilized. Traction views have been largely abandoned in favor of computed tomography, although some surgeons do use traction fluoroscopic images in the operating room just prior to sterile preparation of the surgical field. Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the shoulder is typically performed to further assist in injury classification and preoperative planning, particularly in the setting of fracture dislocations. Three-dimensional reconstructions of these CT scans are extremely helpful to understand the fracture pattern in more detail. [10]

Fracture dislocations can present challenging clinical decisions regarding attempted reduction in the emergency room versus in the operating room with full muscle paralysis [11]. Prompt reduction is recommended to mitigate potential neurovascular complications. However, the potential benefits of closed reduction must be balanced against the risk of iatrogenic fracture propagation and displacement (Fig. 3). Displacement of an associated surgical neck fracture at the time of attempted closed reduction may have a profound impact on remaining humeral head blood supply as well as treatment options. The same is true for the more uncommon iatrogenic neck fracture at the time of closed reduction. CT imaging of the shoulder should be meticulously scrutinized prior to any reduction attempt to evaluate the proximal humerus for an occult, non-displaced surgical neck fracture. If CT imaging reveals a non-displaced surgical neck fracture, closed reduction under full paralysis versus open reduction are recommended; alternatively, temporary percutaneous fixation of the surgical neck fracture may be consider to reduce the risk of fracture displacement at the time of reduction [11]. There is evidence that larger greater tuberosity fracture size confers greater risk of iatrogenic surgical neck fracture during attempted closed reduction of a greater tuberosity fracture dislocation [12]. As such, these injury patterns should garner strong consideration for closed reduction in the operating room in order to avoid further complications. In the absence of the risk factors noted above, closed reduction of a tuberosity fracture dislocation under sedation is a reasonable course of action. In these instances, care must be taken to ensure the humeral head is not incarcerated on the anterior-inferior or postero-inferior edges of the glenoid with very gentle internal and external rotation prior to any reduction attempt.

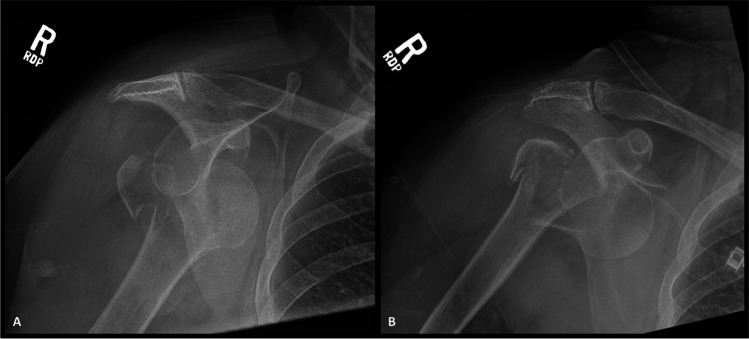

Fig. 3.

Radiographs show AP injury films (A) of a 68-year-old female who presented with a right greater tuberosity proximal humerus fracture dislocation following a ground-level fall. Attempted closed reduction was carried out under conscious sedation, resulting in an iatrogenic surgical neck fracture, as illustrated in post-procedure imaging (B). Given failed closed reduction and injury progression to a 3-part proximal humerus fracture dislocation, non-operative management was no longer possible. The patient subsequently underwent RSA for this injury

Treatment

The selection of nonoperative management versus operative management of a proximal humerus fracture is multifactorial, requiring consideration of fracture pattern, patient age and activity level, medical comorbidities, as well as other traumatic injuries or relevant weight-bearing restrictions, when present. The authors recommend approaching these injuries with a patient-centered approach to aid in achieving optimal management and maximizing outcomes.

Non-operative Management

Non-operative treatment has high success rates for all types of nondisplaced and minimally displaced proximal humerus fractures [13]. Criteria for non-operative management of displaced proximal humerus fractures remain controversial.

In successfully closed reduced tuberosity fracture dislocations, advanced imaging in the form of CT or MR imaging may be useful in determining residual tuberosity displacement. These parameters can provide guidance in the decision for operative versus non-operative management. In patients with non-displaced or minimally displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity, guidelines recommend non-operative treatment for fractures with less than 5–10 mm of displacement in the general population or fractures with less than 3–5 mm of displacement in active patients [14]. Results of randomized prospective controlled trials have shown that immediate mobilization improves short-term pain and function when compared to prolonged immobilization [15]. An example of greater tuberosity fracture dislocation treated successfully with closed reduction followed by non-operative management can be seen in Fig. 4. Non-operative management of more complex proximal humerus fracture dislocations (fractures with a “shield” fragment, 3- and 4-part proximal humerus fracture dislocation, head split fracture dislocation) is typically contra-indicated, although special consideration for nonoperative management in critically ill patients should always be weighed against the risks involved with general anesthesia and surgical intervention. [16]

Fig. 4.

Radiographs show injury films (A) of a 22-year-old male who presented with a right anteroinferior greater tuberosity fracture dislocation. Following successful closed reduction, radiographs (B) and CT imaging (C) were carried out to evaluate residual greater tuberosity displacement and potential need for surgery. As the greater tuberosity was minimally displaced, the patient was treated non-operatively in a shoulder immobilizer. Radiographs at 6-week follow-up (D) reveal healed greater tuberosity fracture

Non-operative management typically involves immobilization of the injured extremity in a sling and non-weight-bearing precautions. Patients are typically maintained on strict shoulder immobilization for the first week following injury with active range of motion of the hand, wrist, and elbow encouraged. The patient can subsequently be progressed to passive range of motion and Codman exercises 2 weeks after the injury followed by active-assisted range of motion (AAROM) at approximately 3 weeks following injury. Typically, active range of motion can be resumed 6 weeks after injury. Strengthening can be resumed 2 months following injury in the setting of pain-free shoulder AROM or radiographs revealing fracture healing, first with isometric exercises and later on using elastic band exercises.

Open Reduction and Internal Fixation

In the setting of proximal humerus fracture dislocations, all irreducible injuries require surgical treatment. Surgery may also be indicated after closed reduction of a dislocation with tuberosity fracture when residual tuberosity displacement is substantial (> 5–10 mm in the general population and > 3–5 mm in active patients) [17]. These displacement parameters are known to alter rotator cuff biomechanics [18, 19]. A case of greater tuberosity fracture dislocation with residual greater tuberosity displacement following closed reduction requiring operative fixation can be seen in Fig. 5. Other classic indications for surgery include open injuries and vascular compromise.

Fig. 5.

Radiographs show injury films (A) of a 35-year-old male who presented with a left anterior greater tuberosity fracture dislocation. Following successful closed reduction confirmed with AP and Velpeau radiographs (B), CT imaging revealed greater tuberosity displacement of 25 mm, as can be appreciated on 3D CT reconstructions (C). The patient underwent arthroscopic repair of the greater tuberosity fragment. Post-operative radiographs (D) reveal anatomic tuberosity reduction. Radiographs at a 3-month follow-up (E) revealed healed greater tuberosity fragment

Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is the treatment of choice in reconstructible, proximal humerus fracture dislocations in non-elderly patients. Generally, ORIF of proximal humerus fractures meeting operative criteria is reserved for active patients typically less than 65 years of age, although physiologic age is more important than chronological age. One study identified age over 60 as an independent risk factor for screw cut-out and complications following proximal humerus fracture ORIF [20]. Additionally, one randomized controlled trial has reported worse results with internal fixation when compared to reverse in patients over the age of 65 [21].

In fracture dislocations with one or both tuberosities fractured and in patients meeting criteria for ORIF, locking plate fixation is most commonly used in North America, given the biomechanical advantage observed in fixed-angle stabilization of proximal humerus fractures with poor bone quality and/or metaphyseal comminution [22, 23]. Intramedullary nailing is selectively considered in other parts of the world as well. An example of a posterior 3-part proximal humerus fracture dislocation that underwent successful operative fixation with locked plating can be seen in Fig. 6.

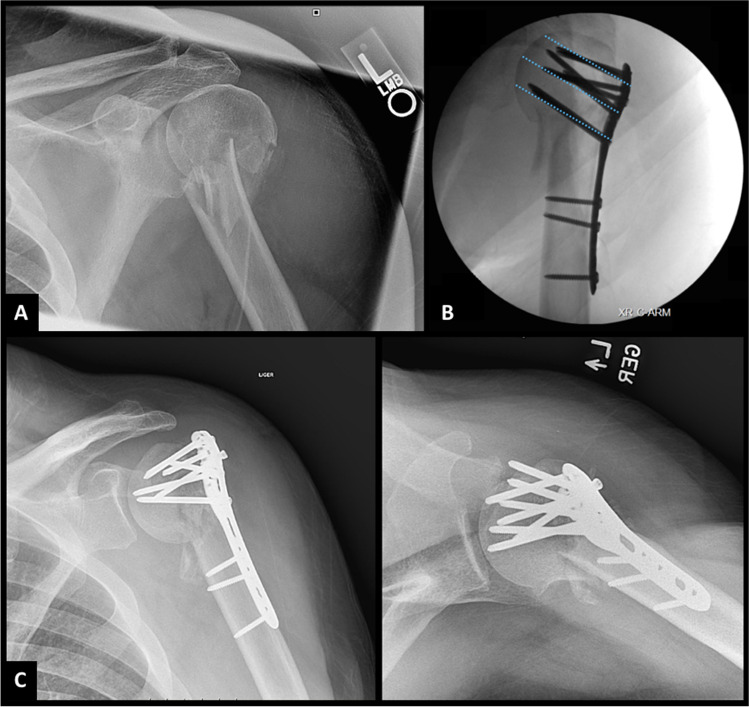

Fig. 6.

Injury radiographs (A) and 3-dimensional CT reconstructions (B) of a 58-year-old female who presented with a posterior, 4-part fracture dislocation of the right glenohumeral joint in addition to an intra-articular scapula fracture following motor vehicle accident. The patient underwent open reduction and internal fixation of her proximal humerus fracture dislocation with locked proximal humerus plating and non-operative management of the minimally displaced intra-articular scapula fracture. Immediate post-operative radiograph (C) reveal anatomic reduction and 14-week follow-up radiographs (D) reveal proximal humerus fracture union

Locking-Plate Fixation: Operative Technique

Surgical approach is largely dependent on surgeon preference. While the deltopectoral approach is the most commonly reported interval and is effective in gaining exposure of most proximal humerus fractures, the anterolateral deltoid-split approach can be useful in certain fracture patterns, in particular for access of a posteriorly displaced greater tuberosity fracture. The authors prefer a deltopectoral approach, given its extensile nature, the ability to use the same approach in the revision setting, and in light of recent RCT data indicating improved outcomes. [24]

Established plate fixation principles should be understood and adhered to when performing fracture fixation in the proximal humerus. First, avoidance of residual displacement of the humeral head and adequate reduction of the tuberosities are needed to provide the best possible outcome. Reduction of the humeral head in slight valgus may be advantageous, and some degree of shortening at the surgical neck level is well tolerated when needed in order to achieve adequate contact and compression. On the contrary, the humeral head must be kept out of varus at the time of fixation, especially in shoulders with calcar comminution. Plate positioning is another important consideration during the treatment of these injuries. Placing the proximal humerus plate too proximal may result in both subacromial impingement and suboptimal calcar screw placement. Generally, locking screws should be placed in a manner to maximize spread within the humeral head. Importantly, the inferior calcar screws should be within the lower 25%, or within the inferior 12 mm, of the humeral head [25]. The length of the inferior calcar screw is best measured and placed under fluoroscopic imaging so that the screw tip is within 5 mm of the subchondral bone [25]. If these principles are not met, the likelihood of fixation failure increases, as exemplified in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Injury radiographs (A) of a 41-year-old male presenting as a poly-trauma patient following motor vehicle accident with a 2-part proximal humerus fracture. Final intra-operative fluoroscopic imaging (B) reveals slight varus alignment of the proximal humerus fracture following locked proximal humerus plating as well as malpositioning of the inferior calcar screw outside of the bottom 25% of the humeral head. Follow-up radiographs (C) reveal fixation failure complicated by recurrent varus deformity and peri-articular screw cut-out

The rate of complications after proximal humerus ORIF is not insignificant. Screw cut-out, commonly cited as the most common complication following operative fixation, has been observed in up to 57% of cases and seems to correlate with both patient age and fracture pattern [20, 26]. As previously stated, patient age over 60 has been identified as an independent risk factor for post-operative complication as well as screw cut-out following operative fixation [20]. The incidence of avascular necrosis (AVN) has been reported to range from 3 to 35% following ORIF, with increased rates observed following operative fixation versus conservative management [20, 27]. Increasing fracture type severity has been observed to be an independent risk factor for AVN following proximal humerus ORIF [20]. Proximal humerus nonunion rates have been observed in as high as 13% of cases following operative fixation [20]. Hertel et al. studied the relationship between humeral head ischemia and proximal humerus fracture morphology and observed the three strongest predictors in order of importance were (1) length of metaphyseal head extension, (2) integrity of the medial hinge, and (3) certain basic fracture patterns [28]. In cases where all three of these risk factors were present, i.e., an anatomic neck fracture with short calcar and disrupted medial hinge, the positive predictive value for humeral head ischemia reached 97%. Interestingly, their study reported a poor association between humeral head ischemia and glenohumeral dislocation (accuracy 0.49) as well as a humeral head split component (accuracy 0.49) [28]. It is important for surgeons to recognize that the presence of humeral head dislocation or reconstructible head split patterns does not preclude operative fixation of proximal humerus fractures, and all attempts should be made to salvage the proximal humerus with ORIF when possible, especially in very young patients. Other identified risk factors that may increase the risk of non-union include age, female sex, smoking, and osteoporosis. [20]

Hemiarthroplasty

Hemiarthroplasty (HA) has largely fallen out of favor in the treatment of proximal humerus fractures given the advances in reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) techniques and comparatively improved outcomes seen in patients treated with either ORIF or RSA [29, 30]. While this technique is being utilized less frequently for proximal humerus fractures, it remains a useful procedure for certain indications, specifically in younger patients (40 to 65 years old) with complex, non-reconstructible articular injuries with or without associated glenohumeral dislocation [4]. Hemiarthroplasty is particularly appealing for the rare isolated anatomic neck fracture dislocations as well as fracture dislocations with a single, large greater tuberosity fracture in males. Tuberosity healing remains the most critical factor in determining successful outcome following hemiarthroplasty [31]. As a result, any patient characteristic or fracture pattern that could prohibit tuberosity healing may be considered a relative contraindication to hemiarthroplasty.

When performing hemiarthroplasty, anatomic reduction and stable fixation of tuberosity position should be a primary surgical goal, as this maximizes rate of tuberosity healing [32]. Malpositioning of the tuberosities results in aberrant glenohumeral joint forces and has been shown to result in worse functional results and higher rates of implant failure [31]. Poor tuberosity reduction will also occur when the prosthetic humeral head is not positioned in the correct height and/or version. The upper edge of the pectoralis major insertion may be used as a landmark for proper height and version of the implant to allow anatomic tuberosity reconstruction [33]. Torrens et al. found that the prosthesis can be placed 5.6 cm above the upper insertion of the pectoralis major to replicate native anatomy with high accuracy. The ‘Black and Tan Technique’ described by Formaini et al. for maximizing tuberosity healing in the setting of a cemented RSA implant is a technique that can also be utilized in hemiarthroplasty [34]. This technique utilizes distal cementation with proximal impaction grafting around the humeral implant to provide an autogenous cancellous bone bed interface to aid in tuberosity healing. Stable fixation of tuberosity is also of utmost importance. Loss of tuberosity fixation will result in an unstable implant, leading to superior implant migration, loss of function, and increased pain [35, 36]. The authors preferred tuberosity fixation technique utilizes four high-strength suture tapes passed in horizontal cerclage fashion around the greater and lesser tuberosity bone tendon junction and through the humeral stem medial suture eyelets to provide fixation between the greater and lesser tuberosities as well as between the tuberosities and the humeral stem. An additional two suture tape cerclages are placed around the proximal humeral metaphysis, and subsequently thrown through the bone tendon junction of the greater and lesser tuberosities, respectively, providing vertically oriented fixation of the tuberosities to the humeral metaphysis. A case of hemiarthroplasty for treatment of a four-part fracture dislocation in a 53-year-old female can be seen in Fig. 8.

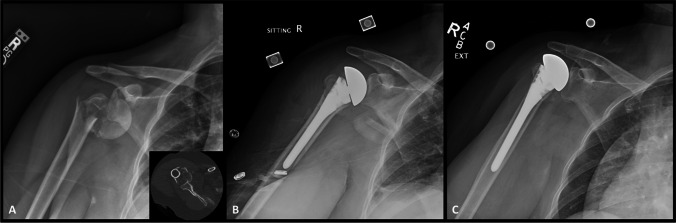

Fig. 8.

Radiograph and CT imaging (A) of a 53-year-old woman presented with a four-part fracture dislocation with greater tuberosity comminution. Intra-operatively, there was concern for humeral head ischemia. Given age, injury pattern, and intra-operative findings, hemiarthroplasty was elected (B). Anatomic reduction of tuberosities was attempted; however, due to comminution and bone loss, a slight overreduction of the tuberosity was accepted in order to provide cortical contact for healing. Radiographs at 12-month follow-up (C) reveal well-healed tuberosities with interval decrease in acromio-humeral interval and slight superior migration of the hemiarthroplasty with respect to the glenoid

Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty

Reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) has become a highly utilized surgical intervention in the treatment of proximal humerus fractures [37]. The main advantage of RSA is that shoulder function and patient outcome are less dependent on tuberosity healing in contrast to both ORIF and HA. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty implant designs medialize the glenohumeral center of rotation and distalize the humerus to varying degrees, which improves the deltoid moment arm and theoretically increases passive muscular tension for more efficient deltoid recruitment during forward flexion and abduction. [38]

When compared to HA, RSA seems to provide better functional outcomes for 3- and 4-part proximal humeral fracture in terms of satisfaction, flexion, and abduction [37]. In patients over the age of 65, there is strong evidence that RSA is superior to plate fixation in severely displaced proximal humerus fractures [21]. Data also suggests that when indications are met to proceed with RSA in a severely displaced proximal humerus fracture, acute treatment is superior to delayed treatment in terms of lower 1-year revision rates, lower surgical post-operative dislocations, and less mechanical complications [39]. Intraoperative complications that may arise include nerve injury and iatrogenic fractures. Postoperative complications may include hematoma, periprosthetic joint infection, dislocation, acromial/scapular spine fractures, scapular notching, and implant loosening [38]. A case of RSA for treatment of a four-part posterior fracture dislocation in a 63-year-old male can be seen in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Injury radiographs (A & B) and 3D CT reconstructions (C) of a 63-year-old male who presented with a right four-part posterior fracture dislocation. Given age and injury pattern, reverse shoulder arthroplasty was elected for surgical intervention. Post-operative radiographs (D) reveal a well-positioned RSA with anatomic tuberosity reduction

When performing RSA for fracture, there are multiple surgical principles that should be followed. Much like hemiarthroplasty, research has shown improved clinical outcomes in patients undergoing RSA for fracture who achieve tuberosity healing [40]. There are several instrumentation and fixation-specific techniques that have been shown to increase likelihood of tuberosity healing following RSA. In regard to instrumentation, fracture-specific humeral stems, which typically employ suture eyelets for tuberosity fixation as well as splined proximal bodies with porous ongrowth surfaces, have been found to be clinically superior to standard arthroplasty stems in the setting of RSA for fracture [41]. Additionally, research has shown that tuberosity healing rates following RSA increase significantly when humeral prothesis inclination is 135° when compared to protheses with either 145° or 155° humeral inclination [40]. Decreased glenosphere lateralization may also play a role in achieving an anatomic tuberosity reduction, allowing improved tuberosity healing, although this remains poorly defined in current literature [42].

Humeral component fixation plays an important role in RSA for fracture. Comminution of the humeral metaphysis typically precludes metaphyseal press-fit fixation at time of surgery. As such, cementation is often utilized for humeral stem fixation [43]. When humeral stem cementation is utilized, the “Black and Tan Technique” previously described may be utilized to promote tuberosity healing with the use of autogenous humeral head bone grafting [34]. Research has shown decreased complication rates with cemented RSA (5.5%) when compared to uncemented RSA (9.7%) [44]. Modern implants that provide a more extended bone-ingrowth coating and stem diameters in 1 mm increments may successfully be used in an uncemented fashion. The same is true for modern long-stemmed, splined, diaphyseal engaging humeral components, which can provide stout humeral component rotational stability in the setting of metaphyseal comminution, which may change how these injuries are approached in the future, although research on these designs remains limited.

Using the superior border of the pectoralis tendon, similar to methods used for HA, can serve as a useful guide in determining humeral component height and version. Cagle et al. suggest that the top of the stem should be 5 cm superior to the upper border of the insertion of the pectoralis major, with the stem cemented in 20° of retroversion [45].

Conclusion

Proximal humerus fracture dislocations are complex injuries that require special considerations. These injuries typically arise from high-energy mechanisms and can be associated with additional injuries, as well as neurovascular compromise. Thorough pre-operative patient evaluation and shared decision-making should be employed in all cases. In addition to non-operative management, ORIF, hemiarthroplasty, and reverse total shoulder replacement are at the surgeon’s disposal, each with their own indications and complication profile. When treated with operative intervention, these complex and technical challenging injuries require thoughtful pre-operative planning and surgical decision-making.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

JTL, NPK, and YA have no conflicts of interest to disclose. JSS serves as a consultant and receives royalties and/or consulting fees from Stryker, Exactech, and Acumed, receives publishing royalties from Elsevier and OUP, receives honorarium from JSES, and has stock in Precision OS and PSI. JDB receives royalties from Stryker.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Passaretti D, Candela V, Sessa P, Gumina S. Epidemiology of proximal humeral fractures: a detailed survey of 711 patients in a metropolitan area. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(12):2117–2124. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Launonen AP, Lepola V, Saranko A, Flinkkila T, Laitinen M, Mattila VM. Epidemiology of proximal humerus fractures. Arch Osteoporos. 2015;10:209. doi: 10.1007/s11657-015-0209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergdahl C, Ekholm C, Wennergren D, Nilsson F, Moller M. Epidemiology and patho-anatomical pattern of 2,011 humeral fractures: data from the Swedish Fracture Register. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:159. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1009-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neer CS. 2nd. Displaced proximal humeral fractures. I. Classification and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52(6):1077–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCausland C, Sawyer E, Eovaldi BJ, Varacallo M. Anatomy, shoulder and upper limb, shoulder muscles. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) 2022. [PubMed]

- 6.Foruria AM, Martinez-Catalan N, Pardos B, Larson D, Barlow J, Sanchez-Sotelo J. Classification of proximal humerus fractures according to pattern recognition is associated with high intraobserver and interobserver agreement. JSES Int. 2022;6(4):563–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jseint.2022.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thorsness R, English C, Gross J, Tyler W, Voloshin I, Gorczyca J. Proximal humerus fractures with associated axillary artery injury. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(11):659–663. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rathore S, Kasha S, Yeggana S. Fracture dislocation of shoulder with brachial plexus palsy: a case report and review of management options. J Orthop Case Rep. 2017;7(2):48–51. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pencle FJ, Varacallo M. Proximal Humerus Fracture. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) 2022. [PubMed]

- 10.Bahrs C, Rolauffs B, Sudkamp NP, Schmal H, Eingartner C, Dietz K, et al. Indications for computed tomography (CT-) diagnostics in proximal humeral fractures: a comparative study of plain radiography and computed tomography. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-10-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green A, Choi P, Lubitz M, Aaron DL, Swart E. Proximal humeral fracture-dislocations: which patterns can be reduced in the emergency department? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022;31(4):792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2021.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo J, Liu Y, Jin L, Yin Y, Hou Z, Zhang Y. Size of greater tuberosity fragment: a risk of iatrogenic injury during shoulder dislocation reduction. Int Orthop. 2019;43(5):1215–1222. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-4022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rangan A, Handoll H, Brealey S, Jefferson L, Keding A, Martin BC, et al. Surgical vs nonsurgical treatment of adults with displaced fractures of the proximal humerus: the PROFHER randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(10):1037–1047. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rath E, Alkrinawi N, Levy O, Debbi R, Amar E, Atoun E. Minimally displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity: outcome of non-operative treatment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(10):e8–e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodgson SA, Mawson SJ, Saxton JM, Stanley D. Rehabilitation of two-part fractures of the neck of the humerus (two-year follow-up) J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(2):143–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edelson G, Kelly I, Vigder F, Reis ND. A three-dimensional classification for fractures of the proximal humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(3):413–425. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.86b3.14428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rouleau DM, Mutch J, Laflamme GY. Surgical treatment of displaced greater tuberosity fractures of the humerus. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24(1):46–56. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Platzer P, Kutscha-Lissberg F, Lehr S, Vecsei V, Gaebler C. The influence of displacement on shoulder function in patients with minimally displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity. Injury. 2005;36(10):1185–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bono CM, Renard R, Levine RG, Levy AS. Effect of displacement of fractures of the greater tuberosity on the mechanics of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(7):1056–1062. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b7.10516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boesmueller S, Wech M, Gregori M, Domaszewski F, Bukaty A, Fialka C, et al. Risk factors for humeral head necrosis and non-union after plating in proximal humeral fractures. Injury. 2016;47(2):350–355. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fraser AN, Bjordal J, Wagle TM, Karlberg AC, Lien OA, Eilertsen L, et al. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty is superior to plate fixation at 2 years for displaced proximal humeral fractures in the elderly: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102(6):477–485. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.19.01071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haidukewych GJ. Innovations in locking plate technology. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12(4):205–12. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200407000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Omid R, Trasolini NA, Stone MA, Namdari S. Principles of locking plate fixation of proximal humerus fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29(11):e523–e535. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rouleau DM, Balg F, Benoit B, Leduc S, Malo M, Vezina F, et al. Deltopectoral vs. deltoid split approach for proximal HUmerus fracture fixation with locking plate: a prospective Randomized study (HURA) J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29(11):2190–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Padegimas EM, Zmistowski B, Lawrence C, Palmquist A, Nicholson TA, Namdari S. Defining optimal calcar screw positioning in proximal humerus fracture fixation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(11):1931–1937. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters PM, Plachel F, Danzinger V, Novi M, Mardian S, Scheibel M, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes after surgical treatment of proximal humeral fractures with head-split component. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102(1):68–75. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.19.00320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu J, Zhang C, Wang T. Avascular necrosis in proximal humeral fractures in patients treated with operative fixation: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014;9:31. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-9-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hertel R, Hempfing A, Stiehler M, Leunig M. Predictors of humeral head ischemia after intracapsular fracture of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(4):427–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorsness R, Shields E, Chen RE, Owens K, Gorczyca J, Voloshin I. Open reduction and internal fixation versus hemiarthroplasty in the management of complex articular fractures and fracture-dislocations of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Arthroplast. 2017;1:2471549217709364. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sebastia-Forcada E, Cebrian-Gomez R, Lizaur-Utrilla A, Gil-Guillen V. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty for acute proximal humeral fractures. A blinded, randomized, controlled, prospective study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(10):1419–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chambers L, Dines JS, Lorich DG, Dines DM. Hemiarthroplasty for proximal humerus fractures. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2013;6(1):57–62. doi: 10.1007/s12178-012-9152-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huffman GR, Itamura JM, McGarry MH, Duong L, Gililland J, Tibone JE, et al. Neer Award 2006: Biomechanical assessment of inferior tuberosity placement during hemiarthroplasty for four-part proximal humeral fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(2):189–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torrens C, Corrales M, Melendo E, Solano A, Rodriguez-Baeza A, Caceres E. The pectoralis major tendon as a reference for restoring humeral length and retroversion with hemiarthroplasty for fracture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(6):947–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Formaini NT, Everding NG, Levy JC, Rosas S. Tuberosity healing after reverse shoulder arthroplasty for acute proximal humerus fractures: the “black and tan” technique. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(11):e299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boileau P, Krishnan SG, Tinsi L, Walch G, Coste JS, Mole D. Tuberosity malposition and migration: reasons for poor outcomes after hemiarthroplasty for displaced fractures of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(5):401–12. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.124527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu J, Li SH, Cai ZD, Lou LM, Wu X, Zhu YC, et al. Outcomes, and factors affecting outcomes, following shoulder hemiarthroplasty for proximal humeral fracture repair. J Orthop Sci. 2011;16(5):565–572. doi: 10.1007/s00776-011-0113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jonsson EO, Ekholm C, Salomonsson B, Demir Y, Olerud P, Collaborators in the SSG Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty provides better shoulder function than hemiarthroplasty for displaced 3- and 4-part proximal humeral fractures in patients aged 70 years or older: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30(5):994–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou HS, Chung JS, Yi PH, Li X, Price MD. Management of complications after reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2015;8(1):92–97. doi: 10.1007/s12178-014-9252-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seidel HD, Bhattacharjee S, Koh JL, Strelzow JA, Shi LL. Acute versus delayed reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the primary treatment of proximal humeral fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29(19):832–839. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-01375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Sullivan J, Ladermann A, Parsons BO, Werner B, Steinbeck J, Tokish JM, et al. A systematic review of tuberosity healing and outcomes following reverse shoulder arthroplasty for fracture according to humeral inclination of the prosthesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29(9):1938–1949. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Onggo JR, Nambiar M, Onggo JD, Hau R, Pennington R, Wang KK. Improved functional outcome and tuberosity healing in patients treated with fracture stems than nonfracture stems during shoulder arthroplasty for proximal humeral fracture: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30(3):695–705. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmalzl J, Jessen M, Sadler N, Lehmann LJ, Gerhardt C. High tuberosity healing rate associated with better functional outcome following primary reverse shoulder arthroplasty for proximal humeral fractures with a 135 degrees prosthesis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s12891-020-3060-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barlow JD, Bartels DW, Parkes CW, Sanchez-Sotelo J. High rate of anatomic reduction and healing of tuberosities with a fracture specific cemented stem in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for proximal humerus fracture. Seminars in Arthroplasty: JSES. 2021 2021/11/01/;31(4):696–702.

- 44.Rossi LA, Tanoira I, Ranalletta M, Kunze KN, Farivar D, Perry A, et al. Cemented vs. uncemented reverse shoulder arthroplasty for proximal humeral fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022;31(3):e101–e19. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2021.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cagle PJ, Jr, Reizner W, Parsons BO. A technique for humeral prosthesis placement in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for fracture. Shoulder Elbow. 2019;11(6):459–464. doi: 10.1177/1758573218793904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]