Abstract

Objective: To assess the efficacy of 0.1% cyclosporine A (CsA) cationic emulsion (CE) in the treatment of dry eye disease (DED) in terms of ocular surface disease index (OSDI).

Methods: DED patients with corneal fluorescein staining grade (CFS) ≤ 3 on the Oxford scale and Schirmer test score < 10 mm/ 5 min were enrolled for once-daily CsA use in this observational, prospective, one-center study. Efficacy of CE at 30, 60, and 90-day follow-up visit was evaluated using OSDI questionnaire. Both the overall OSDI score and the outcomes for all subscales - ocular symptoms (OS), vision-related function (VRF) and environmental triggers (ET) were considered.

Results: Twelve patients (10 women and 2 men), whose baseline OSDI ranged between 27.08 and 70.03 mm (48.2 ± 11.8), were included. Their achieved mean scores for subscales such OS, VRF and ET were 66.6 ± 16.8, 42.2 ± 12.0 and 42.2 ± 12.5, respectively. Statistically significant results were obtained after 30 days for OSDI (45.5 ± 10.0; p=0.011), whereas after 90 days for both OSDI (35.4 ± 7.4; p=0.003) and OS (47.2 ± 10.9; p=0.005), VRF (30.5 ± 6.1; p=0.003) and ET (33.3 ± 11.2; p=0.008).

Conclusions: CsA CE significantly reduced symptoms of patients with DED. Recovery was the most successful after 90 days of treatment and included OSDI, OS, VRF and ET.

Abbreviations: CE = cationic emulsion, CFS = corneal fluorescein staining, CsA = cyclosporine A, DED = dry eye disease, ET = environmental triggers, OS = ocular symptoms, OSDI = ocular surface disease index, VRF = vision-related function

Keywords: cyclosporine A, cationic emulsion, dry eye disease, ocular surface disease index

Introduction

Report of the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society International Dry Eye Workshop II concluded that DED is a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface, characterized by a loss of homeostasis of the tear film, and accompanied by ocular symptoms, in which tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities play etiological roles [1,2]. DED affects from 5 up to even 50% of the population [3]. DED patients complain not only of pain and sore eyes, which are sensitive to light, but also of difficulties performing basic activities of daily living, such as using a computer and driving, which are caused by visual problems such as blurry vision [4,5]. Without treatment, DED can progress, becoming more resistant to medicaments and potentially leading to permanent ocular damage [2,6].

Current treatment strategies for DED have largely been restricted to use various artificial tear formulations, which provide only short-term relief from DED symptoms and do not address ocular surface inflammation, which is the main pathophysiological component of DED [7,8]. Topical steroids have been shown to be effective in reducing the symptoms and signs of DED, however, their ocular side-effects, such as intraocular hypertension and cataract, exclude them form long-term therapy [9]. So, it has become obvious that other anti-inflammatory agents should be used in the treatment of DED. CsA has shown significant benefits in moderate to severe DED and has been the focus of investigation in recent years [2,7,9,10-12]. CsA is a lipophilic drug, so only its CE may prolong pre-corneal residence time, increase its bioavailability at the ocular surface, as well as improve corneal penetration [9,13,14].

The research methodology in DED is most often based on CFS, on the Oxford scale, Schirmer test score without anesthesia, tear breakup time, rarely corneal/ conjunctival lissamine green staining score on van Bijsterveld scale [7,9,13,15-17]. Only a few authors have considered the OSDI to estimate the efficacy of the treatment [2,9], though DEWS II report recommends the use of the OSDI (Allergan Inc, California, USA) for the assessment of the symptoms of DED [18]. The OSDI is an outcome of popular questionnaire that evaluates both symptom frequency and health-related quality of life [19]. It contains 12 questions divided into three subscales: OS - questions 1-3, VRF - questions 4-9 and ET - questions 10-12, shown in Table 1 [19].

Table 1.

Ocular surface disease questionnaire

| Ocular surface disease questionnaire | ||||||

| Have you experienced any of the following during the last week? | None | Some | Half | Most | All | |

| 1. Eyes that are sensitive to light? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | |

| 2. Eyes that feel gritty? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | |

| 3. Painful or sore eyes? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | |

| 4. Blurred vision? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | |

| 5. Poor vision? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | |

| Have problems with your eyes limited you in performing any of the following during the last week? | N/A | None | Some | Half | Most | All |

| 6. Reading? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 7. Driving at night? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 8. Working with a computer? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 9. Watching TV? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Have your eyes felt uncomfortable in any of the following situations during the last week? | N/A | None | Some | Half | Most | All |

| 10. Windy conditions? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 11. Places with low humidity (very dry)? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 12. Areas that are air conditioned? | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

The advantages of OSDI include its translation and validation in many languages [20,21], as well as the possibility of its implementation without patient observation, which was especially valuable during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study using the OSDI aimed to assess the efficacy of 0.1% CsA CE in the treatment of DED, in terms related to the frequency of symptoms and health-related quality of life of the patient.

Material and methods

The study enrolled adult patients with DED determined by CFS grade ≤ 3 on Oxford scale [22], a Schirmer test score without anesthesia < 10 mm/ 5 min. [23], as well as an OSDI score ≥ 23 [9], and was carried out between December 2019 and February 2021. Rigorous exclusion criteria were applied, such BCVA less than 0.5, the history of eye surgery, as well as other eye diseases.

The study was conducted adhering to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Each patient signed an informed consent for routine pharmacological treatment.

All the patients administered 1 drop of unpreserved single-dose 0.1% cyclosporine A cationic emulsion once daily at bedtime. Each of them filled out an OSDI questionnaire four times, i.e. at baseline, on the thirtieth, the sixtieth and the ninetieth day of treatment.

Then, the total OSDI score was calculated using the following formula:

where the severity was graded on a scale of 0 = none of the time, 1 = some of the time, 2 = half of the time, 3 = most of the time, 4 = all the time.

Additionally, subscales scores were computed as it follows:

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistica 13.1 package. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant unless it was necessary to apply Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons that reduced the significance level down to even 0.017. The Friedman ANOVA test was used to check statistically significant differences in the severity of the symptoms/ signs between consecutively completed questionnaires. Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to determine significant differences between specific questionnaires, i.e. 0 versus 30, 0 versus 60, and 0 versus 90.

Results

Twelve adult patients (10 women - 83.3% and 2 men - 16.7%) in the age range between 49 and 75 (mean 63.5 ± 7.3), were included in the study. The baseline OSDI of the studied eyes ranged between 27.1 and 70.0 (48.2 ± 11.8).

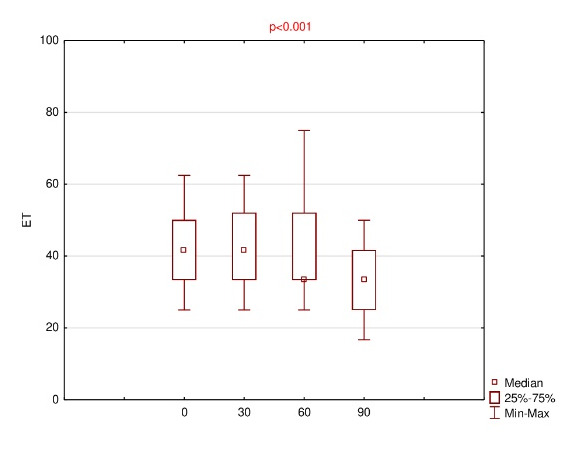

Detailed results of OSDI, OS, VRF and ET for baseline and follow-up visits were summarized using descriptive statistics - mean, standard deviation (SD), median, range and listed in Fig. 1-4.

Fig. 1.

Results of OSDI for baseline (0) and follow-up (30th, 60th, 90th day of the treatment)

Fig. 4.

Results of environmental triggers (ET) for baseline (0) and follow-up (30th, 60th, 90th day of the treatment)

Fig. 2.

Results of ocular symptoms (OS) for baseline (0) and follow-up (30th, 60th, 90th day of the treatment)

Fig. 3.

Results of vision-related function (VRF) for baseline (0) and follow-up (30th, 60th, 90th day of the treatment)

The mean OSDI score reduced on subsequent visit up to 35.4 ± 7.4 at the end. The results of the mean of all subscales were finally decreased; however, for OS, the mean 60 > mean 30 (61.8 ± 16.5 and 61.1 ± 13.5, respectively). Anyway, using ANOVA Friedman test, it was realized that p<0.001, which was lower than the significance level both for OSDI and all subscales, e.g. OS, VRF and ET.

Therefore, using Wilcoxon signed rank test, statistically significant differences were observed for variables pairs 0 versus 30 (p=0.011) and 0 versus 90 (p=0.003) in the case of OSDI, and for pairs 0 versus 90 in the case of each of the subscales, i.e. OS, VRF and ET (p= 0.005, 0.003 and 0.008, respectively).

Discussion

DED is one of the most common ophthalmic diseases with a great impact on the quality of life [3-5,7,9,16]. Although we have many drugs to treat DED, we are still looking for new substances that will improve the comfort of DED patients [2,7,9,11,24].

This study demonstrated that 0.1% CsA CE significantly decreased OSDI score after 90 days of the treatment (from median of 47.8 to 33.3). Moreover, a statistical reduction also applies to the results of all the subscales, i.e. OS, VRF, ET (from median of 66.7 to 50; 39.6 to 29.2; 41.7 to 33.3; respectively).

Miller et al. agreed that the overall OSDI score defined the ocular surface as normal (0-12 points), or as having mild (13-22 points), moderate (23-32 points) or severe (33-100 points) DED. In their multicenter study involving 310 patients, they proved that the minimal clinically important difference ranged from 7.0 to 9.9 for all OSDI categories, while from 4.5 to 7.3 for mild or moderate and from 7.3 to 13.4 for severe DED [19]. The baseline OSDI of all the patients in this study was more than 27 (moderate or severe DED) and the difference of OSDI, median after 90 days of 0.1% CsA CE treatment, was 14.4, which was more than minimal clinically important.

The SANSIKA study, conducted in 50 centers in 9 European countries as 6-month, randomized, double-masked, vehicle-controlled research, accepted patients with at least 30% improvement of OSDI as responders to the treatment of DED with 0.1% CsA CE [7]. Similar criteria used by Baudouin et al. in their SANSIKA’s open-label 6-month extension involved 177 patients [9]. In this study, 30.33% reduction of OSDI was achieved after 3 months of treatment with 0.1% CsA CE, which proved its efficacy.

In this study, a statistically significant mild improvement of OSDI (47.8 versus 45.8) was obtained after 30 days. It was related to anti-inflammatory properties of CsA [16,25]. In the SANSIKA study, Leonardi et al. observed a significant decrease in human leucocyte antigen DR (HLA-DR) expression after only 1 month of CsA treatment [7]. The effect of CsA on the reduction of HLA-DR expression was observed in the SICCANOVE study, which was conducted in 61 sites located in 6 European countries involving 492 patients [16].

There were several limitations to the study. Firstly, relatively few patients were enrolled in the study. However, research on the efficacy of CsA in the treatment of DED in the Scottish University Teaching Hospital also involved a small number of patients [26]. Concomitant use of artificial tears was permitted, which might have confounded the interpretation of CsA CE effect. However, artificial tears were allowed even in the SANSIKA study [7,9]. Additionally, OSDI was the only tool to assess the efficacy of CsA CE. But, in their study, Schiffman et al. involved 139 patients and proved that OSDI demonstrated good sensitivity and specificity in the evaluation of severity of DED [27]. However, it is worth mentioning that the study lasted 16 months to avoid the biases from seasonal and weather-related conditions [28].

Conclusions

The study showed that the CsA CE has a good efficacy in the treatment of DED. It reduces the patients’ symptoms and improves their quality of life. Additionally, the study proved that the OSDI is a simply but efficacious tool to assess the force of the cure of DED. Although the reliability of the presented results could be limited due to a small number of the studied group, the whole concept of such method, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the contact with the patient was restricted, seemed promising.

Conflict of Interest statement

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent and Human and Animal Rights statement

Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

Authorization for the use of human subjects

Ethical approval: The research related to human use complies with all the relevant national regulations, institutional policies, is in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, and has been approved by the Ethical Committee of MW med Eye Centre, Cracow, Poland.

Acknowledgements

None.

Sources of Funding

None.

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, Caffery B, Dua HS, Joo CK, Liu Z, Nelson JD, Nichols JJ, Tsubota K, Stapleton F. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul Surf. 2017 Jul;15(3):276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.008. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leonardi A, Messmer EM, Labetoulle M, Amrane M, Garrigue JS, Ismail D, Sainz-de-la-Manza M, Figueiredo FC, Baudouin C. Efficacy and safety of 0.1% ciclosporin A cationic emulsion in dry eye disease: a pooled analysis of two double-masked, randomised, vehicle-controlled phase III clinical studies. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019 Jan;103(1):125–131. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-311801. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-311801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stapleton F, Alves M, Bunya VY, Jalbert I, Lekhanont K, Malet F, Na KS, Schaumberg D, Uchino M, Vehof J, Viso E, Vitale S, Jones L. TFOS DEWS II epidemiology report. Ocul Surf. 2017 Jul;15(3):334–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.003. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labetoulle M, Rolando M, Baudoin C, van Setten G. Patients’ perception of DED and its relation with time to diagnosis and quality of life: an international and multilingual survey. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017 Aug;101(8):1100–1105. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-309193. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-309193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Figueiredo F, Baudoin C, Rolando M, Messmer EM, van Setten G, Garrigue JS, Garrigos G, Labetoulle M. The Enduring Experience in Dry Eye Diagnosis: a Non-Interventional Study Comparing the Experiences of Patients Living with and without Sjögren’s Syndrome. Ophthalmol Ther. 2021 Jun;10(2):321–335. doi: 10.1007/s40123-021-00341-6. doi: 10.1007/s40123-021-00341-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baudoin C, Aragona P, Messmer EM, Tomlinson A, Calonge M, Boboridis KG, Akova YA, Geerling G, Labetoulle M, Rolando M. Role of hyperosmolarity in the pathogenesis and management of dry eye disease: proceedings of the OCEAN group meeting. Ocul Surf. 2013 Oct;11(4):246–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2013.07.003. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leonardi A, Van Setten G, Amrane M, Ismail D, Garrigue JS, Figueiredo FC, Baudouin C. Efficacy and safety of 0.1% cyclosporine A cationic emulsion in the treatment of severe dry eye disease: a multicenter randomized trial. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2016 Jun 10;26(4):287–296. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000779. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bron AJ, de Pavia CS, Chauhan SK, Bonini S, Gabison EE, Jain S, Knop E, Markoulli M, Ogawa Y, Perez V, Uchino Y, Yokoi N, Zoukhri D, Sullivan DA. TFOS DEWS II pathophysiology report. Ocul Surf. 2017 Jul;15(3):438–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.011. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baudoin C, de la Maza MS, Amrane M, Garrigue JS, Ismail D, Figueiredo FC, Leonardi A. One-Year Efficacy and Safety of 0.1% Cyclosporine a cationic Emulsion in the Treatment of Severe Dry Eye Disease. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2017 Nov 8;27(6):678–685. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5001002. doi: 10.5301/ejo.50001002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plugfelder SC. Antiinflammatory therapy for dry eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004 Feb;137(2):337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.10.036. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Labbe A, Baudoin C, Ismail D, Amrane M, Garrigue JS, Leonardi A, Figueiredo FC, van Setten G, Labetoulle M. Pan-European survey of the topical ocular use of cyclosporine A. J Fr Ophthalmol. 2017 Mar;40:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2016.12.004. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nebiosso M, Alisi L, Giovannetti F, Armentano M, Lambiase A. Eye drop emulsion containing 0.1% cyclosporin (1mg/mL) for the treatment of severe vernal keratoconjunctivitis: an evidence-based review and place in therapy. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019 Jul 5;13:1147–1155. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S181811. doi: 10.2147/OPHT.S181811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy O, Labbé A, Borderie V, Laroche L, Bouheraoua N. Topical cyclosporine in ophthalmology: Pharmacology and clinical indications. J Fr Ophthalmol. 2016 Mar;39(3):292–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2015.11.008. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daull P, Lallemand F, Garrigue JS. Benefits of cetalkonium chloride cationic oil-in-water nanoemulsions for topical ophthalmic drug delivery. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2014 Apr;66(4):531–541. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12075. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhahir RK, Al-Nima AM, Al-Bazzaz FY. Nanoemulsions as Ophthalmic Drug Delivery Systems. Nanoemulsions as Ophthalmic Drug Delivery Systems. 2021 Oct 28;18(5):652–664. doi: 10.4274/tjps.galenos.2020.59319. doi: 10.4274/tjps.galenos.2020.59319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pisella P-J, Labetoulle M, Doan S, Cochener-Lambard B, Amrane M, Ismail D, Creuzot-Garcher C, Baudouin C. Topical ocular 0.1% cyclosporine A cationic emulsion in dry eye disease patients with severe keratitis: experience through the French early-access program. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018 Feb 5;12:289–299. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S150957. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S150957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baudoin C, Figueiredo FC, Messmer EM, Ismail D, Amrane M, Garrigue JS, Bonini S, Leonardi A. A randomized study of the efficacy and safety of 0.1% cyclosporine A cationic emulsion in treatment of moderate to severe dry eye. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2017 Aug 30;27(5):520–530. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000952. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daull P, Feraille L, Barabino S, Cimbolini N, Antonelli S, Mauro V, Garrigue JS. Efficacy of a new topical cationic emulsion of cyclosporine A on dry eye clinical signs in an experimental mouse model of dry eye. Exp Eye Res. 2016 Dec;153:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2016.10.016. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2016.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chatterjee S, Agrawal D, Chaturvedi P. Ocular Surface Disease Index © and the five-item dry eye questionnaire: a comparison in Indian patients with dry eye disease. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021 Sep;69(9):2396–2400. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_3345_20. doi: 104103/ijo.IJO_3345_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller KL, Walt JG, Mink DV, Satram-Hoang S, Wilson SE, Perry HD, Asbell PA, Pflugfelder SC. Minimal clinically important difference for the ocular surface disease index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010 Jan;128(1):94–101. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.356. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Midorikawa-Inomata A, Inomata T, Nojiri S, Nakamura M, Iwagami M, Fujimoto K, Okumura Y, Iwata N, Eguchi A, Hasegawa H, Kinouchi H, Murakami A, Kobayashi H. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the ocular surface disease index for dry eye disease. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e033940. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033940. doi: 101136/bmjopen-2019-033940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bakkar MM, El-Sharif AK, Al Qadire MA. Validation of the Arabic version of the Ocular Surface Disease Index Questionnaire. Int J Ophthalmol. 2021 Oct 18;14(10):1595–1601. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2021.10.18. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2021.10.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Begley C, Caffery B, Chalmers R, Situ P, Simpson T, Nelson JD. Review and analysis of grading scales for ocular surface staining. Ocul Surf. 2019 Apr;17(2):208–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2019.01.004. doi: 1016/j.jtos.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers R, Djalilian A, Dogru M, Dumbleton K, Gupta PK, Karpecki P, Lazreg S, Pult H, Sullivan BD, Tomlinson A, Tong L, Villani E, Yoon KC, Jones L, Craig JP. TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology report. Ocul Surf. 2017 Jul;15(3):539–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.001. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones L, Downie LE, Korb D, Benitez-Del-Castillo JM, Dana R, Deng SX, Dong PN, Geerling G, Hida RY, Liu Y, Seo KY, Tauber J, Wakamatsu TH, Xu J, Wolffsohn JS, Craig J. TFOS DEWS II Management and Therapy Report. Ocul Surf. 2017 Jul;15(3):575–628. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.006. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donnenfeld E, Pflugfelder SC. Topical ophthalmic cyclosporine: pharmacology and clinical uses. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009 May-Jun;54(3):321–338. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2009.02.002. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hind J, Macdonald E, Lockington D. Real-world experience at a Scottish university teaching hospital regarding the tolerability and persistence with topical Ciclosporin 0.1% (Ikervis) treatment in patients with dry eye disease. Eye (Lond) 2019 Apr;33(4):685–686. doi: 10.1038/s41433-018-0289-7. doi: 10.1038/s41433-018-0289-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, Hirsch JD, Reis BL. Reliability and validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000 May;118(5):615–621. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.5.615. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]