Abstract

Background

Right ventricular failure (RVF) in patients with a continuous-flow left ventricle assist device (CF-LVAD) is associated with higher incidence of mortality. This systematic review aims to assess the overall proportion of RVF and the pre-operative echocardiographic parameters which are best correlating to RVF.

Methods

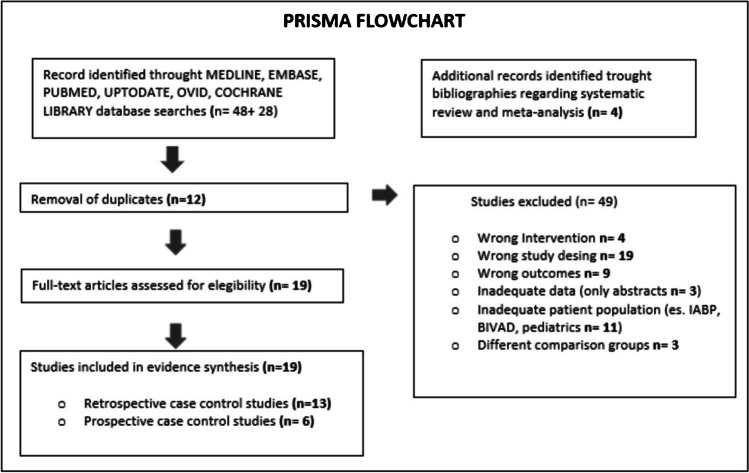

A systematic research was conducted between 2008 and 2019 on MEDLINE, EMBASE, PUBMED, UPTODATE, OVID, COCHRANE LIBRARY, and Google Scholar electronic databases by performing a PRISMA flowchart. All observational studies regarding echocardiographic predictors of RVF in patients undergoing CF-LVAD implantation were included.

Results

A total number of 19 observational human studies published between 2008 and 2019 were included. We identified 524 RVF patients out of a pooled final population of 1741 patients. The RVF overall proportion was 28.25% with 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.24–0.34. The highest variability of perioperative echocardiographic parameters between the RVF and no right ventricular failure (NO-RVF) groups has been found with tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), fractional area change (FAC), and right ventricular global longitudinal strain (RVGLS). Their standardized mean deviation (SMD) was − 0.33 (95% CI − 0.54 to − 0.11; p value 0.003), − 0.34 (95% CI − 0.53 to − 0.15; p value 0.0001), and 0.52 (95% CI 0.79 to 0.25; p value 0.0001), respectively.

Conclusions

The echocardiographic predictors of RVF after CF-LVAD placement are still uncertain. However, there seems to be a trend of statistical correlation between TAPSE, FAC, and RVGLS with RVF event after CF-LVAD placement.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12055-022-01447-7.

Keywords: Right ventricular failure, Continuous-flow LVAD, Echocardiographic assessment, Advanced heart failure

Introduction

Implantation of continuous-flow left ventricular assist device (CF-LVAD) is indicated for selected patients with acute and chronic advanced heart failure (AHF) [1]. Complications associated with CF-LVAD and other mechanical cardiac support (MCS) devices have been described previously with right ventricular failure (RVF) being one of the most frequently reported complications [2].

RVF in patients implanted with a CF-LVAD placement is associated with higher incidence of acute renal injury and increased mortality [3]. The proportion of RVF after CF-LVAD placement ranges between 3 and 40% depending in part on definition: (1) early acute RVF, where a right ventricular assist device (RVAD) is required before the patient leaves the operating room; (2) early post-operative RVF (RVAD within 30 days of CF-LVAD, with failure to wean from inotropic/vasopressor support within 14 days and/or death within 14 days of implant with diagnosis of RVF); and (3) late RVF (need for RVAD after > 30 days after CF-LVAD, or hospitalization requiring intravenous diuretics or inotropic support and association with RVF symptoms) [2, 4].

In the immediate post-operative period, these complications are attributed to the increase in pump speed, which leads to a “suck down” of the left ventricle (LV) and a leftward shift of the interventricular septum (IVS).

The latter may lead to an acute and progressive dilation of the right ventricle (RV) and the onset of tricuspid regurgitation (TR) and to ventricular-arterial uncoupling. Such complications are potentially fatal [5–7].

At this time, there is no approved MCS as destination therapy for the right heart only or for biventricular support. This limits the utility of left ventricular assist devices in patients with RVF.

Therefore, it is essential to select appropriate candidates for CF-LVAD who have sufficient RV reserve and to pursue diagnostic avenues, for example, echocardiographic assessments, haemodynamic parameters, or other biomarkers, to see if there are any specific parameters that can indicate, pre-operatively, a patient’s predisposition to post-CF-LVAD development of RVF [8].

For instance, the late referral of patients with AHF has been shown to be correlated with higher incidence of RVF post-CF-LVAD implantation [9]. That’s why the American Heart Association (AHA) has recently published guidance for timely and appropriate referral of patients with AHF, where Morris et al. suggest the mnemonic I-NEED-HELP (Inotropes-New York Heart Association (NYHA) class/Natriuretic Peptides/End Organ Dysfunction/Ejection Fraction/Defibrillator Shocks/Hospitalizations/Edema/Low Pressure/Prognostic Medication) acronym as a good method to identify patients that can be take advantages from CF-LVAD implantation [10, 11].

However, RVF is a heterogeneous syndrome, rather than a single pathology, where the RV is unable to meet the blood flow demands without excessive use of the Frank-Starling curve [12]. The most commonly used clinical definition of acute RVF, described in the classification of mechanical cardiac support (i.e., INTERMACS, EUROMACS), does not precisely identify this phenomenon [13].

Current definitions are based on nonspecific clinical findings, which may be secondary to left ventricular dysfunction. Moreover, in certain circumstances, a RVF diagnosis may result from exclusion criteria. These are some of the reasons why the proportion of RVF after CF-LVAD placement ranges widely from 3 to 40% in the literature [4].

Several multiparametric scores for early diagnosis of RVF may be adopted in clinical practice [14]. Nevertheless, a meta-analysis by Bellavia et al. reports that there are no demographic or biometric parameters able to stratify the risk of RVF [15].

The present meta-analysis aims to evaluate whether echocardiography may be used to assess RVF events after LVAD implantation. However, we need to consider that a quantitative echocardiographic approach may be not sufficient and that a qualitative approach is also needed.

A qualitative approach is an experience-driven operator dependent evaluation (“eyeballing”) of the RV walls (lateral, anterior, inferior, coronal view) through a multiplane approach analyzing the RV tridimensional (3D) shape. The quantitative approach takes into consideration all the two-dimensional (2D) and 3D echocardiographic parameters, together with myocardial deformation imaging, known as global longitudinal strain (GLS) [16–20].

Myocardial strain/strain reflects the deformation of cardiac muscle and quantifies the myocardial systolic function. It can be obtained either from speckle-training echography (STE) or from tissue Doppler imaging (TDI). By the speckle motion analysis in the 2D ultrasonic images, this technique allows a non-Doppler angle-independent objective assessment of myocardial deformation, with the possibility to quantify the thickening, shortening, and rotation dynamics of cardiac function. Since this technique does not require a Doppler imaging, the analysis is relatively angle-independent and is marginally affected by cardiac in-plane motion artefacts [21].

Cumulatively, these echocardiographic parameters can provide information about the perioperative status of the RV and its reaction to the new pump [22].

So far, randomized control trials (RCTs) assessing the echocardiographic power in predicting the risk of RVF after CF-LVAD implantation are still lacking, and literature is composed mainly by case series and single-center observational studies with heterogeneous sample populations [19, 20, 23–39].

This systematic review summarizes the contemporary challenge in finding a common definition of acute RVF in CF-LVAD patients and aims to focus on the “echocardiographic state of the art” parameters of RVF assessment after LVAD placement.

The aim of this study is to assess the overall proportion of RVF and the pre-operative echocardiographic parameters which are best correlated to RVF after CF-LVAD implantation.

Statistical method

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic literature search of all studies regarding the echocardiographic assessment of RVF after LVAD placement on the following electronic medical databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PUBMED, UPTODATE, OVID, COCHRANE LIBRARY, and Google Scholar.

Keywords used were as follows: “Left Ventricular Assist Device,” “LVAD,” “Left Ventricular Assist Support,” “Right Ventricular function,” “candidate selection,” “Echocardiography,” “assessment,” “evaluation,” “strain,” combined with “prediction,” “Right ventricular Failure,” “severe Right ventricular Failure,” “Acute Right Ventricular Failure.”

The literature search was restricted to scientific papers in the English language and to studies where the minimum age of the participants enrolled was 18 years of age. We selected only adult patients in order to restrict the field of investigation and include the most possible homogeneous groups of patients.

Two different investigators performed the original search independently (G.P. and L.N.). The results of the original research were then discussed with a third investigator (M.B.). The three investigators had to reach a consensus on the eligibility of all studies by performing a PRISMA flowchart [40], i.e., flowchart of evidence search and selection of studies about echocardiographic predictors of RVF in patients undergoing CF-LVAD implantation.

As we recognized the statistical limit of dealing with observational studies, we assessed their quality by using the 18 criteria of Delphi technique [41]. All studies included in the systematic review analysis had received at least 14 “yes,” so that they were all considered sufficient quality and then were assessed for eligibility.

The publications which met the inclusion criteria were carefully scrutinized to identify the perioperative echocardiographic RV function in CF-LVAD patients. We systematically reviewed all the available studies comparing patients who developed acute severe RVF after CF-LVAD placement (RVF group) with patients who did not develop such complications (NO-RVF group). For each publication, we identified the RVF definition, and the echocardiographic parameters related to the perioperative RV function. We did not consider the echocardiographic parameters measured only once across the studies. We did not consider adult population features (gender, geographic distribution, range of age).

We did not consider the purpose of CF-LVAD therapy in each study (destination therapy, bridge to transplant, or bridge to recovery).

Consensus was required for each echocardiographic parameter reported in the data collection. Two reviewers abstracted the data together (M.B. and L.N.). Any conflicting data recordings were solved by an independent senior evaluator (M.Ba.).

Identification of the most significant echocardiographic variables related to the risk of RVF was primarily based on quantification of the effect size (ES) obtained as standardized mean deviation (SMD), since we were studying continuous variables.

It expresses the size of the event (RVF) effect in each study relative to the variability observed in that study. The p value for the overall ES was calculated using a Z-score.

Since continuous variables have been used, we defined the ES of each parameter by the difference between the mean values in the 2 groups (RVF and NO-RVF). The result was divided by the standard deviation (SD) of each study in order to obtain the SMD. We displayed the results in forest plots for each echocardiographic parameter.

Eligibility criteria

We included all observational studies regarding echocardiographic predictors of RVF in adult patients undergoing CF-LVAD implantation.

Studies that provided insufficient data (for example, only abstracts), pediatric patients, patients scheduled to receive a pulsatile-flow LVAD, and patients receiving additional use of intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) or biventricular assist devices (BIVAD) were excluded.

Results

We identified 76 studies during our initial electronic database search. We identified four more studies regarding how to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis. We removed twelve duplicates. We assessed nineteen full-text observational studies for eligibility (raw data are provided as Supplementary material 1, 2, 3). All researchers agreed with the study eligibility criteria and the studies included in the quantitative synthesis were prospective case control studies (n = 6) and retrospective case control studies (n = 13).

Figure 1 displays the PRISMA flowchart of included and excluded studies. A total of 19 observational human studies published between 2008 and 2019 regarding the perioperative echocardiographic RV function in CF-LVAD patients were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis performed using a STATA software version 14.2.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart

The collected data for each study are reported in Table 1 and Table 2. Table 1 reports study characteristics, including year of publication, first author’s last name, type of study (observational, retrospective, prospective), definition criteria of acute RVF, sample size, and RVF proportion. Table 2 displays the main echocardiographic parameters discussed in all studies and how often they have been reported in all studies.

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Author | Year | Type of study | Acute RVF Definition |

Sample size | RVF (n) | RVF proportion/percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beck et al. [25] | 2017 | Retrospective cohort | Need for RV mechanical support device, inotropic and/or inhaled pulmonary vasodilator requirements for > 14 days | 57 | 21 | 36.84 |

| Silverton et al. [26] | 2018 | Retrospective,observational | Either 14 consecutive days of inotrope therapy or subsequent RVAD implantation | 100 | 19 | 19.00 |

| Aymami et al. [28] | 2018 | Retrospective | INTERMACS Definition: sustained elevation of central venous pressure > 16 mmHg and the need for prolonged inotropes beyond 7 days, or the unplanned need for RV assist device (RVAD) implantation | 158 | 60 | 37.97 |

| Boegershausen et al. [29] | 2017 | Retrospective |

INTERMACS Definition: The need for an RV assist device or (ii) the requirement of inhaled nitric oxide or inotropic therapy for > 1 week any time after LVAD implantation in the presence of symptoms and signs of persistent RV dysfunction, such as central venous pressure (CVP) > 18 mmHg with a cardiac index 18 mmHg, cardiac tamponade, ventricular arrhythmias or pneumothorax |

54 | 13 | 24.07 |

| Kalogeropoulos et al. [48] | 2016 | Single-center prospective | Symptoms and signs of persistent RV dysfunction (defined as central venous pressure .18 mmHg with a cardiac index, 2.0 L/min/m2 in the absence of pulmonary capillary wedge pressure .18 mmHg, tamponade, ventricular arrhythmias, or pneumothorax), requiring RVAD or inhaled nitric oxide (or other pulmonary vasodilator) or inotropic therapy for .7 days any time after LVAD implantation | 38 | 15 | 39.47 |

| Charisopoulou et al. [24] | 2019 | Retrospective | Need of RVAD | 70 | 14 | 20.00 |

| Grant et al. [27] | 2012 | Observational | Unplanned insertion of an RVAD or the use of an intravenous inotropes for > 14 days post-operatively | 117 | 47 | 40.17 |

| Kato et al. [30] | 2013 | Prospective | Need for RVAD, inotropic support at 14 days after surgery or inhaled or oral pulmonary vasodilators at 14 days after surgery | 68 | 24 | 35.29 |

| Vivo et al. [31] | 2013 | Prospective | Requirement of a RVAD or ≥ 14 consecutive days of inotropic support | 109 | 25 | 22.94 |

| Sugiyama Kato et al. [32] | 2012 | Observational | Unexpected RV assist devices requirement, nitric oxide inhalation > 48 h, and/or inotropic support > 14 days | 111 | 21 | 18.92 |

| Kukucka et al. [33] | 2011 | Prospective | The occurrence of 2 of the following criteria in the absence of cardiac tamponade within the first 48 h after surgery: mean arterial pressure < 55 mmHg, central venous pressure > 16 mmHg, mixed venous saturation < 55%, cardiac index < 2 l/min/m2, inotropic support > 20 units | 115 | 15 | 13.04 |

| Puwanant et al. [34] | 2008 | Retrospective | The need for inotropic support or pulmonary vasodilators for > 14 days post-operatively | 33 | 11 | 33.33 |

| Topilsky et al. [35] | 2011 | Retrospective | A need for an RV assist device or inotropic support for more than 7 days post-operatively | 83 | 23 | 27.71 |

| Gudejko et al. [36] | 2019 | Retrospective cohort | INTERMACS Definition, meeting one or more of the following criteria: the need for a RV mechanical support device (RVAD) or need for inotropic/inhaled pulmonary vasodilator for > 14 days post-operatively | 85 | 28 | 32.94 |

| Magunia et al. [18] | 2018 | Single-center retrospective | Prolonged inotropic support for > 14 days after LVAD implantation or consecutive implantation of a right ventricular assist device | 26 | 5 | 19.23 |

| Drakos et al. [19] | 2010 | Prospective | The need for inhaled nitric oxide for > 48 h or intravenous inotropes for > 14 days and/or right ventricular assist device implantation | 175 | 77 | 44.00 |

| Potapov et al. [37] | 2008 | Retrospective | The presence of two of the following criteria in the first 48 h after surgery: mean arterial pressure 55 mmHg; central venous pressure 16 mmHg; mixed venous saturation 55%; cardiac index liters/min/m2; inotropic support score 20 units; or need for an RVAD | 54 | 9 | 16.67 |

| Baumwol et al. [38] | 2011 | Retrospective | Patients requiring continuous post-operative inotropes for > 14 days; inhalati onal nitric oxide (iNO) > 48 h or the need for sildenafil/iloprost on cessation of iNO; or requiring right-sided mechanical support, with venous-pulmonary artery extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VPA-ECMO) | 40 | 13 | 32.50 |

| Amsallem et al. [23] | 2019 | Retrospective | Symptoms or findings of persistent RV failure characterized by both of the following: documentation of elevated central venous pressure (direct invasive measurement with evidence of a central venous pressure or RAP > 16 mmHg, or findings of significantly dilated inferior vena cava with absence of inspiratory variation by echocardiography, or clinical findings of elevated jugular venous distension) and manifestations of elevated central venous pressure (i.e., peripheral edema, ascites, or palpable hepatomegaly on physical examination or by diagnostic imaging or laboratory evidence of worsening hepatic [total bilirubin > 2.0 mg/dL] or renal dysfunction [creatinine > 2.0 mg/dL]) | 194 | 75 | 38.66 |

Table 2.

Echocardiographic parameters

| Echographic parameter | Comments | N of studies |

|---|---|---|

|

TAPSE mm Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (Normal cutoff: > 16 mm) |

- Parameter of global RV function which describes apex-to-base shortening - M-mode alignment-dependent measurement - Strongly influenced by changes in volume and preload - TAPSE increase in response to dobutamine infusion |

13 |

|

FAC % Fractional area change (Normal cutoff: ≥ 35%) |

- The % of area change within the RV between diastole and systole, an estimate of the RV systolic function - The need to have a good visualization of the endocardium - Greatly influenced by the type of performed technique (trans-thoracic or trans-esophageal) |

11 |

|

RVGLS — % Right ventricular longitudinal strain (Negative value, cutoff not universally recognized) |

- Index of quantitative analysis of regional myocardial deformation in different RV segments - Independent of global cardiac movement |

6 |

|

RVEDD to LVEDD ratio Right ventricular end diastolic diameter to left ventricular end diastolic diameter ratio (Cutoff not universally recognized: the value > 0.72 correlates with RVF across the studies) |

- Right-heart anatomic parameters ratio, describing acute geometric deformation - Conflicting results on its efficacy in predicting RVF across the studies |

4 |

|

TDI (S□) cm/s Tissue Doppler Imaging (Normal cutoff > 10) |

- Systolic ejection rate with pulsed Doppler on the lateral tricuspid ring - Dependent on the correct US alignment |

2 |

|

E/e′ ratio Early diastolic (E) velocity of the right ventricular free wall at the tricuspid annulus assessed with tissue Doppler and the early diastolic tricuspid annulus velocity (e′) ratio (Normal cutoff influenced by age, gender, and cardiac disease) |

- Grading a diastolic dysfunction as it represent a reliable noninvasive surrogate for RV diastolic pressures - It could be acutely augmented the more increasing in the pump speed, the more increasing in the leftward shift of interventricular septum and in right ventricular venous return, but it has not been statistically proven |

2 |

|

LSR OF RV FW — % Longitudinal systolic strain of right ventricular free wall (Negative value, cutoff not universally recognized) |

- The degree of RV FW myocardial deformation - It assesses regional myocardial function, more independently of t the LVAD induced geometrical deformations |

4 |

|

RVEDA cm2 Right ventricular end diastolic area (Normal cutoff: 18 ± 5) |

- Using 2D echocardiography, RV size can be measured from a 4-chamber view obtained from the apical window at end-diastole. Although quantitative validation is lacking, qualitatively, the right ventricle should appear smaller than the left ventricle and usually no more than two thirds the size of the left ventricle in the standard apical 4-chamber view | 4 |

|

RV-MPI Right ventricular index of myocardial performance (Normal cutoff: 0.44 ± 0.08) |

- The ratio between the sum of the times of the isovolumic periods and the ejection time for the RV - The MPI is a parameter of global function, combining information on both systole and diastole |

3 |

|

RV long axis mm Right ventricular long axis (Normal cutoff: 56–86) |

- The longitudinal dimension is drawn from the plane of the tricuspid annulus to the RV apex | 3 |

|

RV basal diameter mm Right ventricular basal diameter (Normal cutoff: 24–42) |

----The maximal short-axis dimension in the basal one third of the right ventricle seen on the 4-chamber view | 2 |

The INTERMACS criteria were the most used across the studies (i.e., death or hospitalization including any of the following: prolonged inotropic support ≥ 14 days of iNO ventilation ≥ 14 days; RV mechanical support; urgent heart transplantation) [13].

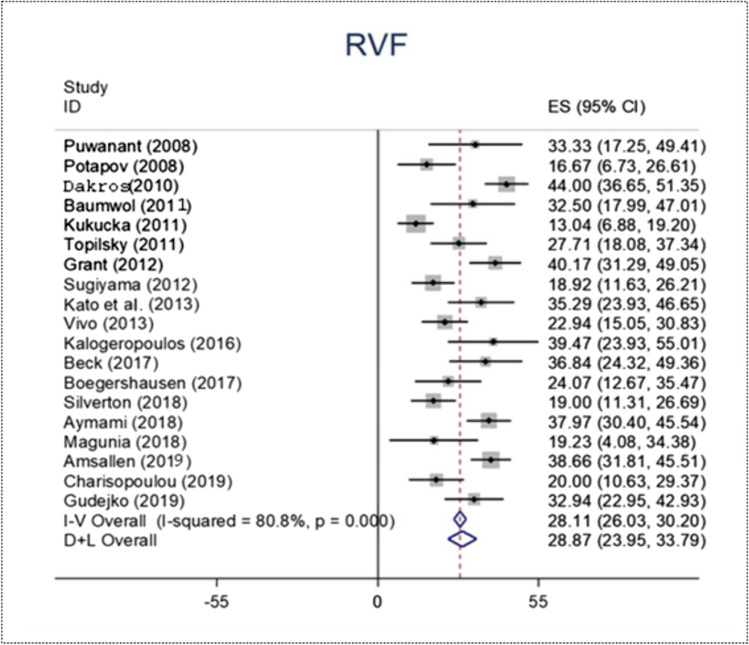

We identified 524 RVF patients out of a pooled final population of 1741 patients. The RVF overall proportion was 28.25% with 95% CI 0.24–0.34 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of RVF proportion

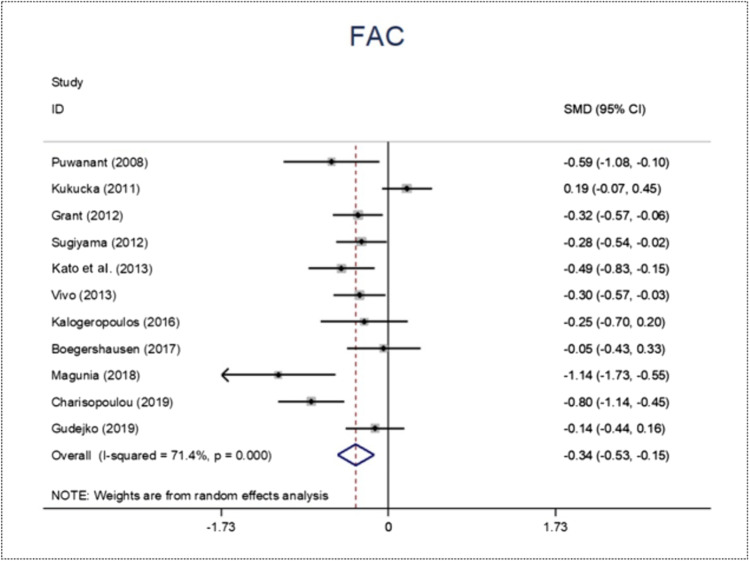

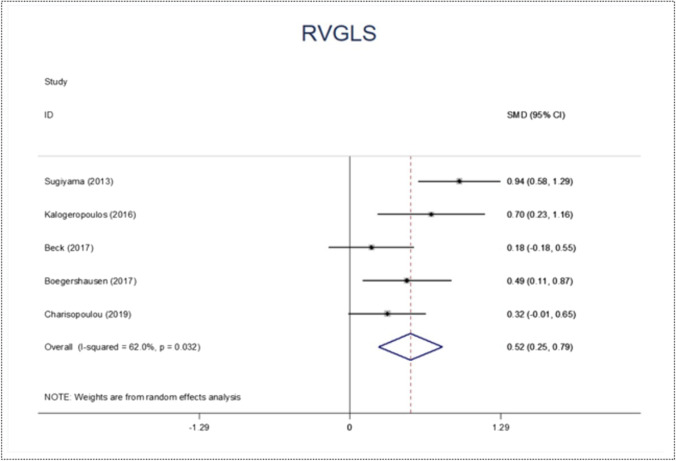

The highest variability of perioperative echocardiographic parameters between RVF and NO-RVF groups has been found with tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), fractional area change (FAC), and right ventricular global longitudinal strain (RVGLS). Figures 2, 3, 4, and 5 display the forest plot for RVF proportion, TAPSE, FAC, and RVGLS, respectively. Their SMD was − 0.33 (95% CI − 0.54 to − 0.11; p value 0.003) (Fig. 3), − 0.34 (95% CI − 0.53 to − 0.15; p value 0.0001) (Fig. 4), and − 0.52 (95% CI − 0.79 to 0.25; p value 0.0001) (Fig. 5), respectively.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE)

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of fractional area change (FAC)

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of right ventricular global longitudinal strain (RVGLS)

Meta-analysis and meta-regression would have been performed by using the Dersimonian and Laird method for variance estimator. However, the extreme result variability and heterogeneity across the studies (I-squared 80.8; p 0.000) made this impossible.

Discussion

RVF is a frequent complication arising after CF-LVAD implantation. It can dramatically affect the clinical outcomes of implanted patients. In our study, the overall RVF proportion among the pooled patient population was 28.25%, with 95% CI 0.24–0.34 (Fig. 2). This result is in line with Liu et al.’s findings. They reported a 3 to 40% incidence of RVF in CF-LVAD-implanted patients [4]. Such results are worrisome and predicting RVF recurrence after CF-LVAD is mandatory to select the ideal patients and to make this MCS device as beneficial as possible.

In their meta-analysis, Bellavia et al. have reported the data about CF-LVAD preimplantation assessment [15]. They found correlations between some invasive, noninvasive, biochemical, and clinical parameters with the RVF event. In particular, the need for mechanical ventilation (MV) or continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), the international normalized ratio (INR) and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), right ventricular stroke work index (RVSWI), and central venous pressure (CVP) were the variables with the highest ES in predicting RVF. Among the echocardiographic parameters, the longitudinal systolic strain of RV free wall showed the highest ES but also the greatest heterogeneity, so that it was only marginally significant (p = 0.05).

After a CF-LVAD placement, and in general following a cardiac surgery, a mechanical and inflammatory insult occurs [42].

The regional contractility of the right ventricle is changed from longitudinal to a more transverse orientation. Equally, the CF-LVAD-induced deformation of the RV alters its degree of deformability and therefore its performance [2, 4].

An independent echocardiographic parameter able to quantify the intrinsic functional reserve of the right ventricle, regardless of the type of the device and the effects related to cardiopulmonary by-pass and anesthesia (vasoplegia, RV, and IVS stunning), could be the ideal one.

In this meta-analysis, we decided to focus on the RV echocardiographic parameters which may be correlated to RVF in patients who are candidates to CF-LVAD implantation. We are aware that echocardiographic RV evaluation may be challenging and that obtaining reliable data may be difficult. This is mainly due to the particular RV anatomy, i.e., its small size and triangular shape. For this reason, the RV has been neglected for a long time, whereas the structure and function of the LV have been studied extensively.

Furthermore, given the absence of RCTs about the echocardiographic predictors of RV function after CF-LVAD implantation, the role of echocardiography in this field is still unclear and lacks strong statistical significance.

In addition, there are concerns about cutoff values of echocardiographic parameters that may predict a significant increase of severe RVF proportion after LVAD placement.

Liu et al. report that some quantitative measures of RV size and function have been developed as important evaluation criteria of RVF. However, they confirm that currently no singular measurements can be used in predicting RVF with certainty [4].

In other words, is there a “magic range” for every single echocardiographic parameter?

In this meta-analysis, there seems to be a trend of statistical correlation between TAPSE, FAC, and RVGLS with RVF after CF-LVAD placement, even if the small sample size and high degree of heterogeneity across studies made this correlation not statistically significant.

TAPSE is frequently related to RV function assessment in literature [43, 44]. In our study, we observed a significant SMD representing the difference of TAPSE values between the groups with and without RVF. However, the p value of this correlation was not so strong (p = 0.003), and this makes this report to be interpreted with caution.

TAPSE is likely not a strong indicator of RV function in patients with severe RV dysfunction. This lack of reliability may be explained by the way that TAPSE quantifies a M-mode alignment-dependent measurement, and it is strongly influenced by changes in volume and preload, rather than being directly dependent on the intrinsic function of the RV [43, 44].

With a clearer statistical significance, we found FAC to be a likely indicator of RVF occurrence after insertion of a CF-LVAD. This result is in line with the meta-analysis of L.-E. Chriqui et al., where the RVF group presented a significantly lower FAC compared to the group without RVF, with a summary SMD of − 2.61% (95% CI − 4.12 to − 1.09%; p value 0.0001) [45].

The European guidelines confirm the role of FAC in offering a reliable indication of RV systolic function evaluation [44]. They state that a 35% cutoff value is suggestive of systolic dysfunction. However, in our study, most pooled patients already presented a FAC value < 35% before surgery. As a consequence, the concern is that FAC can be an interesting parameter in predicting RVF events, but further studies are needed in order to set a cutoff value for the preimplantation setting.

Recent highlights in strain analysis by 2D speckle tracking echocardiography (STE) showed that right atrium and ventricle strain analyses by STE are independent and more sensitive than conventional echocardiography in predicting the need of right ventricular assist device (RVAD) following a LVAD placement, especially for right atrium longitudinal strain, RV free wall longitudinal strain, intra-RV dyssynchrony (RV free wall to septal peak strain difference), and interventricular dyssynchrony (RV free wall to left ventricle free wall peak strain time difference) [46, 47].

In our study, this parameter was likely to be a good predictor of RVF events after CF-LVAD implantation. The difference of RVLGS value between the groups with and without RVF was significant (p = 0.0001).

A RV free wall strain (RV FWS) cutoff value of − 9.6% was found to have an incremental predictive value of RVF (76% specificity; 68% sensitivity) in literature [48].

Conversely, in a more recent retrospective study, Dufendach et al. demonstrated that RVGLS was not associated with post-LVAD RVF (OR = 1.07, p = 0.29) [49].

Bellavia et al. suggest the usefulness of RV FWS, which presents the highest effect size (SMD 0.73), but also the greatest heterogeneity (I2 = 74%) and it is thus marginally significant (p = 0.05) [15].

A recent prospective study by the same group confirms its usefulness and effectiveness even in the distinction between acute and chronic RVF, which is beyond our interest in this study [46].

Limitations

Despite the potential benefit of a pooled analysis, there are several limitations of our current meta-analysis. Firstly, selection biases are prone for observational studies as discussed earlier, but this cannot be avoided because no RCTs in echocardiographic predictors of RVF events have been found.

Secondly, the experience of the operator plays a significant role in the echocardiographic measurements and could differ among studies.

Finally, the viability of the investigation could decrease when taking into account the heterogeneity of patient populations, especially for demographics and primary outcomes being assessed.

Conclusions

Predicting the RVF event after CF-LVAD implantation cannot depend on one single parameter, because several factors including clinical assessment, as well as hemodynamics, biochemical markers, and imaging, need to be considered together.

However, some echocardiographic parameters can help us to identify patients at higher risk of RVF occurrence.

We focused on echocardiographic assessments and found that TAPSE can have a role in predicting RVF, but other parameters, such as FAC and RVGLS, may be more reliable.

However, most of the studies analyzed in this meta-analysis are single-center observational studies. Further studies are needed along with a more systematic and reproducible echocardiographic approach in a more homogeneous study population to clarify the RV behavior.

We can conclude by saying that finally “Cinderella goes to the party” [50]. If the prince has been the left ventricle for ages, the physiology of LVADs showed how life-threatening RV may be. A valid predictivity of the RV’s behavior is needed in order to promptly treat its failure.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not needed being a meta-analysis.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not sought, as this study utilized previously published material, and all data utilized was already deidentified.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and animal rights

Not needed being a meta-analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Key messages

What is known:

- RVF is a life-threatening event in patients with CF-LVAD, but its incidence and prediction are still unclear

- RVF definition remains a challenge, especially in patients with mechanical assist devices.

What is new:

- Demographic and clinical features are not useful to stratify the RVF risk in CF-LVAD population.

- We have to adopt a systematic and reproducible echocardiographic evaluation on homogeneous study samples.

- Strain analysis by 2D speckle tracking echocardiography (STE) is an independent and sensitive parameter able to significantly predict the need of RVAD following a CF-LVAD placement.

References

- 1.McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:3599–3726. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kormos RL, Antonides CFJ, Goldstein DJ, et al. Updated definitions of adverse events for trials and registries of mechanical circulatory support: A consensus statement of the mechanical circulatory support academic research consortium. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39:735–750. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2020.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurihara C, Critsinelis AC, Kawabori M, et al. Frequency and consequences of right-sided heart failure after continuous-flow left ventricular assist device implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2018;121:336–342. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu H, Jones TE, Jeng E, Peng KL, Peng YG. Risk stratification and optimization to prevent right heart failure during left ventricular assist device implantation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2021;35:3385–3393. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2020.09.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheehan F, Redington A. The right ventricle: anatomy, physiology and clinical imaging. Heart. 2008;94:1510–1515. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.132779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harjola V-P, Mebazaa A, Čelutkienė J, et al. Contemporary management of acute right ventricular failure: a statement from the Heart Failure Association and the Working Group on Pulmonary Circulation and Right Ventricular Function of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:226–241. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Houston BA, Shah KB, Mehra MR, Tedford RJ. A new "twist" on right heart failure with left ventricular assist systems. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36:701–707. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2017.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner KR. Right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device placement-The beginning of the end or just another challenge? J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2019;33:1105–1121. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2018.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seferovic PM, Ponikowski P, Anker SD, et al. Clinical practice update on heart failure 2019: pharmacotherapy, procedures, devices and patient management. An expert consensus meeting report of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:1169–1186. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris AA, Khazanie P, Drazner MH, et al. Guidance for timely and appropriate referral of patients with advanced heart failure: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;144:e238–e250. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumwol J. "I Need Help"-A mnemonic to aid timely referral in advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36:593–594. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vieillard-Baron A, Naeije R, Haddad F, et al. Diagnostic workup, etiologies and management of acute right ventricle failure : A state-of-the-art paper. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:774–790. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LaRue SJ, Raymer DS, Pierce BR, Nassif ME, Sparrow CT, Vader JM. Clinical outcomes associated with INTERMACS-defined right heart failure after left ventricular assist device implantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36:475–477. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2016.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frankfurter C, Molinero M, Vishram-Nielsen JKK, et al. Predicting the risk of right ventricular failure in patients undergoing left ventricular assist device implantation: A systematic review. Circ Heart Fail. 2020;13:e006994. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.120.006994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellavia D, Iacovoni A, Scardulla C, et al. Prediction of right ventricular failure after ventricular assist device implant: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:926–946. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paluszkiewicz L, Börgermann J. The value of echocardiographic examination in predicting right ventricular heart failure in patients after the implantation of continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2018;27:931–937. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivy303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiernan MS, French AL, DeNofrio D, et al. Preoperative three-dimensional echocardiography to assess risk of right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device surgery. J Card Fail. 2015;21:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magunia H, Dietrich C, Langer HF, et al. 3D echocardiography derived right ventricular function is associated with right ventricular failure and mid-term survival after left ventricular assist device implantation. Int J Cardiol. 2018;272:348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drakos SG, Janicki L, Horne BD, et al. Risk factors predictive of right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:1030–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kavarana MN, Pessin-Minsley MS, Urtecho J, et al. Right ventricular dysfunction and organ failure in left ventricular assist device recipients: A continuing problem. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:745–750. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03406-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mondillo S, Galderisi M, Mele D, et al. Speckle-tracking echocardiography: a new technique for assessing myocardial function. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30:71–83. doi: 10.7863/jum.2011.30.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Bradburn MJ. Statistical method failure and mid-term survival after left ventricular assist device implantation. Int J Cardiol. 2018;272:348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amsallem M, Aymami M, Hiesinger W, et al. Right ventricular load adaptability metrics in patients undergoing left ventricular assist device implantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;157:1023–1033.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.08.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charisopoulou D, Banner NR, Demetrescu C, Simon AR, Rahman HS. Right atrial and ventricular echocardiographic strain analysis predicts requirement for right ventricular support after left ventricular assist device implantation. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;20:199–208. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jey065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck DR, Foley L, Rowe JR, et al. Right ventricular longitudinal strain in left ventricular assist device surgery-A retrospective cohort study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2017;31:2096–2102. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2017.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverton NA, Patel R, Zimmerman J, et al. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography and right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device implantation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32:2096–2103. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2018.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grant ADM, Smedira NG, Starling RC, Marwick TH. Independent and incremental role of quantitative right ventricular evaluation for the prediction of right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:521–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aymami M, Amsallem M, Adams J, et al. The incremental value of right ventricular size and strain in the risk assessment of right heart failure post - left ventricular assist device implantation. J Card Fail. 2018;24:823–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boegershausen N, Zayat R, Aljalloud A, et al. Risk factors for the development of right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device implantation—a single-centre retrospective with focus on deformation imaging. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;52:1069–1076. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kato TS, Jiang J, Schulze PC, et al. Serial echocardiography using tissue Doppler and speckle tracking imaging to monitor right ventricular failure before and after left ventricular assist device surgery. JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vivo RP, Cordero-Reyes AM, Qamar U, et al. Increased right-to-left ventricle diameter ratio is a strong predictor of right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:792–799. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugiyama Kato T, Farr M, Schulze PC, et al. Usefulness of two-dimensional echocardiographic parameters of the left side of the heart to predict right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kukucka M, Stepanenko A, Potapov E, et al. Right-to-left ventricular end-diastolic diameter ratio and prediction of right ventricular failure with continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puwanant S, Hamilton KK, Klodell CT, et al. Tricuspid annular motion as a predictor of severe right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device implantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:1102–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Topilsky Y, Oh JK, Atchison FW, et al. Echocardiographic findings in stable outpatients with properly functioning HeartMate II left ventricular assist devices. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24:157–169. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gudejko MD, Gebhardt BR, Zahedi F, et al. Intraoperative hemodynamic and echocardiographic measurements associated with severe right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device implantation. Anesth Analg. 2019;128:25–32. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Potapov EV, Stepanenko A, Dandel M, et al. Tricuspid incompetence and geometry of the right ventricle as predictors of right ventricular function after implantation of a left ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:1275–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baumwol J, Macdonald PS, Keogh AM, et al. Right heart failure and "failure to thrive" after left ventricular assist device: clinical predictors and outcomes. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:888–895. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grant AD, Smedira NG, Starling RC, Marwick TH. Independent and incremental role of quantitative right ventricular evaluation for the prediction of right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:521–8. London, UK: BMJ Publication Group; 2001. Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-Analysis in Context (2nd edition) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moga C, Guo B, Schopflocher D, Harstall C. Development of a quality appraisal tool for case series studies using a modified Delphi technique. Edmonton: Institute of Health Economics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang PC, Haft JW, Romano MA, et al. Right ventricular failure following left ventricular assist device implantation is associated with a preoperative pro-inflammatory response. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;14:80. doi: 10.1186/s13019-019-0895-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, et al. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:685–713. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:233–270. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chriqui L-E, Monney P, Kirsch M, Tozzi P. Prediction of right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device implantation in patients with heart failure: a meta-analysis comparing echocardiographic parameters. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2021;33:784–792. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivab177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bellavia D, Iacovoni A, Agnese V, et al. Usefulness of regional right ventricular and right atrial strain for prediction of early and late right ventricular failure following a left ventricular assist device implant: A machine learning approach. Int J Artif Organs. 2020;43:297–314. doi: 10.1177/0391398819884941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Longobardo L, Suma V, Jain R, et al. Role of two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography strain in the assessment right ventricular systolic function and comparison with conventional parameters. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2017;30:937–946. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2017.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kalogeropoulos AP, Al-Anbari R, Pekarek A, et al. The right ventricular function after left ventricular assist device (RVF-LVAD) study: rationale and preliminary results. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17:429–437. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dufendach KA, Zhu T, Diaz Castrillon C, et al. Pre-implant right ventricular free wall strain predicts post-LVAD right heart failure. J Card Surg. 2021;36:1996–2003. doi: 10.1111/jocs.15479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Di Mauro M. Finally, Cinderella goes to the party. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152:620–621. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.04.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.