Abstract

Objective

Transforming the University of Southern California health care system requires that institutions and organizations position equity, diversity, inclusion (EDI), and anti-racism as central to their missions. The purpose of this administrative case report was to describe a systematic approach taken by an academic physical therapy department to develop a comprehensive antiracism plan that engages all interested and affected parties and includes processes for sustainable, long-term engagement.

Methods

Four strategies contributed to organizational change toward anti-racism: Holding Ourselves Accountable; Developing a Plan; Building Consensus; and Providing Education, Support, and Resources. The attitudes of faculty and staff about racism and anti-racist actions were assessed through surveys at the start of the process and after 1 year. Engagement in activities, meetings, and trainings related to EDI and anti-racism was logged for faculty and staff.

Results

From November 2020 through November 2021, several outcomes were achieved, including: making structural organizational changes; updating faculty merit review to include EDI; developing a bias reporting mechanism; establishing faculty development activities, resources, and groups; and implementing structured efforts to recruit a diverse cohort. Within that year, faculty and staff engaged in 99.32 hours of EDI and anti-racism trainings, workshops, and resource groups. Survey data showed persistent high support and commitment to EDI and anti-racism. Faculty and staff reported that they felt more equipped to identify and address individual and institutional racism and they reported risking their reputations to talk about race more often. Confidence in their ability to identify and resolve conflicts related to microaggressions, cultural insensitivity, and bias improved. However, their self-reported ability to identify and address structural racism remained unchanged.

Conclusion

By approaching anti-racism as transformative rather than performative, an academic physical therapy department was able to develop and implement a comprehensive anti-racism plan with high support and engagement.

Impact

The physical therapy profession has not been immune to racism and health injustice. Organizational change to become anti-racist is imperative for excellence and a necessary challenge to undertake if the physical therapy profession is to transform society and improve the human experience.

Keywords: Anti-Racism, Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Institutional Racism, Race, Social Determinants of Health, Social Justice

Background and Purpose

The physical therapy profession exists and functions within academic and health care systems founded on inequitable policies and practices, ranging from implicit biases seen in admissions,1 hiring and promotion,2 research awards,3 access to health care services,4 and clinical decision making,5 to the long historical record of intentional exclusion of specific racial and ethnic groups in these same systems.6,7 Calls to action across health care and academic institutions intensified in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and reckoning on racial injustice.8–10 These calls to action bring awareness to issues of equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI), but often fall short of directly confronting racism through explicit anti-racism work (Tab. 1).

Table 1.

| Key Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Equity | To treat everyone fairly. An equity emphasis seeks to render justice by deeply considering structural factors that benefit some social groups/communities and harm other social groups/communities. Sometimes justice demands, for the purpose of equity, an unequal response. |

| Diversity | Diversity includes all the ways in which people differ, and it encompasses all the different characteristics that make 1 individual or group different from another. Diversity can be used to describe race, ethnicity, and gender, age, national origin, religion, disability, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, education, marital status, language, and physical appearance among other factors. It also involves different ideas, perspectives, and values. |

| Inclusion | Authentically bringing traditionally excluded individuals and/or groups into processes, activities, and decision/policy making in a way that shares power. |

| Individual racism | Beliefs, attitudes, and actions, which can be conscious or unconscious, that are based on ideas that racial groups exist on a hierarchy favoring, advantaging, or viewing as superior those perceived to be of 1 specific race, usually white, over those of other races. |

| Interpersonal racism | Outward acts expressing implicit or explicit prejudice, discrimination, or support for the idea that racial groups exist on a hierarchy. |

| Institutional / organizational racism | Policies, practices, laws, and cultural norms in organizations or institutions that produce or sustain inequity between racial groups. These often do not explicitly mention race, but the impacts (and sometimes the implicit or explicit intentions) create advantages for 1 racial group and disadvantages for others. |

| Structural racism | The overarching system of racial bias across multiple institutions or society as a whole that produces or sustains racial inequities and perpetuates the idea of racial hierarchies. |

| Anti-racism | Taking action to support written and unwritten laws, rules, procedures, processes, regulations, guidelines, and cultural norms that produce or sustain equity between racial groups. |

All 4 of these goals—equity, diversity, inclusion, and anti-racism—require deliberate action. It is not enough to “not be” racist, exclusive, or inequitable. Directly addressing these goals through the active inclusion of individuals as diverse as the society to be served and the equitable distribution of support and resources to members of society is an imperative for any institutional or organizational mission, which looks to advance the health or education of society.

The purpose of this administrative case report is to describe a systematic approach in an academic physical therapy program to (1) develop a plan to address racism and bring an equity lens across the academic unit, (2) engage all interested and affected parties (faculty, staff, students, and alumni) in executing that plan, and (3) institute sustainable processes to carry that plan forward into future years.

Case Description

The University of Southern California is a private university in Los Angeles, CA, USA with an academic medical center that includes 8 health professions programs, a network of hospitals and outpatient clinics, and numerous interdisciplinary research centers and institutes. The USC Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy has a total enrollment of 483 students in 3 degree programs: Doctor of Physical Therapy (430), Master of Science in Biokinesiology (23), and Doctor of Philosophy in Biokinesiology (30). The Division also has 4 physical therapist residency programs with 21 residents and 3 physical therapist fellowships with 3 fellows. In addition, Division faculty manage patient care within 3 outpatient centers and a 401-bed acute care hospital and conduct movement science research in 16 active research labs. Of the 182 faculty members within the Division, 36 are considered core academic teaching and research faculty, 62 are clinical faculty providing patient care across the clinics and hospital, and 84 are part-time adjunct teaching faculty located across the US teaching in residential and hybrid pathways.

The Administrative Issue

In the summer of 2020, as COVID-19 exposed staggering health disparities and the continued murders of Black Americans sparked a surge of social activism and protest, the Division awoke to the need to respond to the moment. The USC Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy embarked on a self-reflection and planning phase to develop a Comprehensive Anti-Racism Plan that would be implemented in the 2020–2021 academic year. Prior to 2020, the Division had adopted initiatives to improve diversity such as holistic admissions and the development of a diversity committee. In light of local and national events of 2020, it was realized that these initiatives were inadequate, and that the Division’s vision of transforming health care could not be met without EDI and anti-racism as a central part of the mission.5 The Division had long aspired to be leaders and innovators with a strategic vision to “transform healthcare by creating the future in physical therapy,” but a new form of transformation was needed.

Although greater clarity was gained in the need to address EDI and anti-racism to meet the mission and vision, there was no mechanism focused on advancing the Division in these areas. The existing diversity committee, which was established in 2016, did not have a strong leadership role in the Division and had not established itself as a vehicle to advance diversity–related initiatives. It was primarily used to collect and transmit data regarding student diversity outcomes to a central University office and organize EDI–related speakers or presentations. With the support of the Division executive leadership team, members of the already existing diversity committee emerged as leaders to expand the role of this committee and push the beginning stages of the intervention forward.

Intervention: Initiating Change

The intervention was developed in response to an unprecedented time in the nation. In reflecting on what made the intervention successful, we recognized 4 processes: Holding Ourselves Accountable; Developing a Plan; Building Consensus; and Providing Education, Support, and Resources. Engaging in these processes concurrently as opposed to sequentially was crucial for moving the organization forward quickly and effectively (Figure).

Figure.

Organizational anti-racist growth can be conceptualized as a planetary gear set. The central “sun” gear is Holding Ourselves Accountable. It is surrounded by the 3 “planet” gears: Developing a Plan; Building Consensus; and Providing Education, Support, and Resources. The concurrent movement and interaction of the gears generate motion in the “ring” gear: Organizational Anti-Racist Growth. Note that the sun and planet gears are interdependent, meaning headway in 1 organizational process will generate headway in the others, and Holding Ourselves Accountable acts as the link and central driver for sustained anti-racist growth within the organization. Keeping these gears moving results in transformative, not just performative, action toward making the organization more anti-racist and equitable.

Paralleling the implementation science paradigm of the Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycle,11 progression in this intervention was non-linear, allowing plans to adapt as learning occurred. Engaging fluidly and concurrently in all elements of the PDSA cycle allowed for opportunities to understand the problem, receive guidance from the community, and reassessment of needs. This adjustment to the paradigm is affirmed by Safir and Dugan’s12 challenge that “plan” comes 2 steps prior to “study.” They state, “When pursuing equity, how can we plan anything responsive without first listening to those at the margins?”11(p 70) In engaging and empowering the community early on in this process, the “study” stage of the model was where the intervention began. This resulted in a change process that allowed movement toward action without being stalled by preplanning all details of the change process.

Holding Ourselves Accountable

To begin working toward advancing anti-racism and becoming an equity-minded organization, we focused on listening and accepting the issues that were facing us in the nation, profession, and organization in which we work. This process began in a community conversation held on June 2, 2020, where 230 individuals in the Division, including students, faculty, staff, and alumni, engaged in a listening session in the wake of the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, as well as alarming evidence regarding the disproportionate use of force by police against Black people.13 This session was unstructured and offered a time for any members of the Division to share thoughts and concerns. The session was intended as a source for community healing, not research; however, notes were taken during the meeting and 3 themes emerged from the conversation in which individuals who identify as Black shared their concerns and feelings: (1) the personal lived experiences of anti-Black racism were widely unknown to those who did not identify as Black, (2) improving the representation of Black educators, clinicians, and researchers is important and impactful, and (3) white allies have significant power to address racism. The priority of this initial session was to listen to and truly hear the lived experiences of our community, rather than providing immediate solutions.

In the 3 weeks that followed this initial session, 3 open listening sessions among students and 3 open listening sessions among faculty and staff were held. In these sessions, ideas for solutions to address the themes of the community conversation were developed. A note-taker was present at each session. The deidentified notes, comments, reflections from these sessions were reviewed and discussed by Division leadership and the Diversity Committee for the development of priorities and a strategic plan. These solutions included enhancing faculty and student recruitment and retention, expanding curricular and research areas to address societal challenges, and supporting the education and development of all Division members to advance anti-racism.

Developing a Comprehensive Anti-Racism Plan

A Comprehensive Anti-Racism Plan was drafted with input from faculty, staff, and students using the notes from the listening sessions and follow-up meetings. One member of the faculty, who was already on the Diversity Committee, was emerging as the leader of this work in the Division. This faculty member—who later was named Vice Chair of EDI—led this process. The final plan outlined 12 objectives in 9 key areas of the Division (Suppl. Appendix 1). These objectives spanned common actions to improve diversity and inclusion, such as increasing representation of historically minoritized groups across the Division and supporting affinity-based student organizations. The objectives also included explicitly anti-racist actions such as making the community more protective of people of color; educating ourselves about racism in health care education, practice, and research; and creating mechanisms to require and reward faculty for engaging in this work, including the revision of the faculty merit review process.

At the outset of this work, there was a desire for immediate visible action and confidence that change could be initiated while the comprehensive plan was in development. Therefore, as the plan was being drafted, affinity groups were developed, diversity-focused student recruitment efforts were initiated, and a bias incident reporting form was created.

Building Consensus

To increase engagement and build consensus, the draft plan was shared in stages by the Vice Chair of EDI. The plan was first shared with the Division executive leadership team, followed by a small group of students and alumni who had written a letter of concern to the Division regarding recent events. After sharing with these 2 groups, the plan was shared with faculty and staff in a Division faculty meeting and finally with the entire student body and alumni who had engaged in the initial community conversation. All Division members were invited to provide input and propose changes in each stage via use of a collaborative online document as well as via a form for anonymous comments. One regularly scheduled faculty meeting and 1 larger Division-wide meeting were also held to discuss the plan and receive feedback. This feedback was reviewed and integrated into the plan draft by members of the Diversity Committee.

Providing Education, Support, and Resources

A concern that was consistently raised among Division members during follow-up meetings was the need for more education and training on EDI and anti-racism. As a result, multiple avenues for self-education, community discussions, and organized trainings were offered. All faculty and staff were encouraged to attend a University-wide 4-part racial equity program in Fall 2020, and clinical faculty and staff were given paid release time to attend. Within the Division, several educational resource groups were formed for students, faculty, and staff, including anti-racism workshops and discussion groups, a faculty and staff book club, and training sessions on diversity in research. Many of these efforts were led by members of the Division who did not identify as persons of color to limit cultural taxation.14,15 Together, these efforts allowed community members, whether new to or seasoned in social justice and anti-racism to engage, grow, and learn with and from each other in a variety of different settings and times.

To track progress in these areas—developing a plan, building consensus, and providing support—we implemented an annual survey of faculty and staff to assess attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, and skills related to the new Division initiatives. The survey was adapted from a Staff Racial Equity and Inclusion Survey developed by Living Cities,16 which itself compiled items from GARE Employee Survey for Local Governments,17 D5 initiative’s Field Survey,18 Vanessa Daniels’ article “More is Required of Us,”19 as well as best practices from the field. Items framed as statements were answered on a Likert scale with 5 possible responses from “Strongly Agree” (5) to “Strongly Disagree” (1). Items framed as questions were answered on a Likert scale with 5 possible responses from “very much” (5) to “very little” (1). This survey was delivered twice—once in November 2020 and at a 1-year follow-up in November 2021. It is important to note that the initial survey was conducted after 4 months of discussion and action and thus did not reflect the state of the Division prior to beginning this work. Results were reported as the mean and standard deviation of responses, as well as the 95% CI of the difference between the 2 means where a positive change indicates an increase in score from November 2020 to November 2021. A mean score greater than 3.5 indicates the average response fell within the “Agree” or “Strongly Agree” range. A CI that does not include zero indicates a statistically significant change at the ɑ = 0.05 level. Selected results are reported in Table 2 with full survey results in Supplementary Appendix 2.

Table 2.

Selected Faculty and Staff Survey Resultsa

|

Outcomes

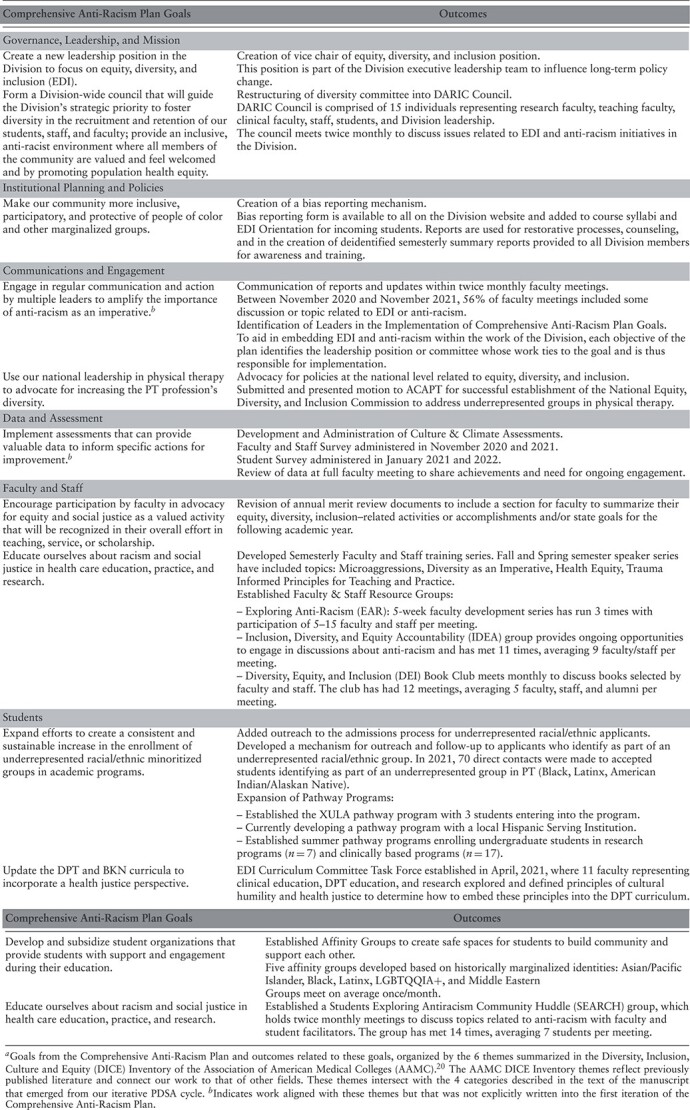

The adoption and implementation of the Division’s first anti-racism plan occurred over a period of 12 months. This plan resulted in several outcomes including structural organizational changes, activities to aid all faculty and staff in bringing an equity lens to their work, engagement of faculty and staff, and changes in faculty and staff perceptions. The Division plan and its resulting outcomes are organized in Table 3 by the 6 themes summarized in the Diversity, Inclusion, Culture and Equity Inventory of the Association of American Medical Colleges.20

Table 3.

Division Initiatives and Outcomesa

|

Structural Organizational Changes

As previously described, a new leadership position, Vice Chair of EDI, was created to ensure that diversity–related issues were considered in higher level decision-making within the Division, as well as to aid and support leadership across the Division in bringing EDI and anti-racism into their work. The Diversity Committee was expanded and reorganized as the Diversity, Anti-Racism, Inclusion, and Community Engagement Council (DARIC) and led by the Vice Chair. Membership was expanded to include students, research faculty, and staff. In addition, administrative staff support was added to assist in organizing and assembling the group. The council met weekly for 3 months to build momentum then slowed to twice-monthly meetings to promote sustainability. Throughout the reorganization process, attention was focused on the Comprehensive Anti-Racism Plan, which would serve to guide the Division on goals aimed at improving racial equity.

Division Activities

Several Division activities were initiated within the first year of work. At the outset, a large focus of the work was on creating avenues to allow for continued listening to the community, supporting faculty and staff development, and encouraging faculty and staff to engage and participate in this work. A bias report mechanism was created to allow community members to share any experiences of bias within the Division. Over the course of the first year, 7 bias reports were received. A process was developed for addressing bias reports and educating Division members on a semiannual basis through the use of anonymized reports. Development of faculty and staff was addressed through a semesterly faculty and staff training series, a 5-week workshop series, and 2 resource groups created to educate faculty and staff on critical topics in the areas of EDI and antiracism. Faculty were encouraged to view EDI and anti-racism as part of their work through the revision of annual faculty merit review. In the revised merit review documents, items related to advancing EDI in the Division were added to self-assessment rubrics and faculty were provided space to include equity diversity, inclusion and anti-racism activities, and goals for the following academic year in the areas of scholarship, teaching, and service.

Faculty and Staff Engagement

For such a large and ambitious plan to be successfully implemented, engaging faculty, staff, students, and alumni, and empowering Division members to take on leadership roles were essential. From November 2020 to November 2021, 32 (18%) faculty and staff served on 3 DARIC subcommittees and 2 work groups related to the plan. In addition, 7 (4%) faculty created and led 3 educational resource groups, organizing 32 separate meetings with attendance ranging from 5 to 15 faculty and staff per meeting. Three outside speakers were invited to provide an educational session to faculty and staff with attendance ranging from 59 to 74 (32–41%). In total, 99.32 hours of Division activities and training related to EDI and anti-racism occurred during the study period.

Faculty and Staff Perceptions

The perception of the Division’s commitment to change and ability to implement change was high in the initial survey (commitment: mean = 4.12 [SD = 0.61]; ability: mean = 3.92 [SD = 0.58]) and showed no change after 1 year (commitment: mean = 4.20 [SD = 0.70], 95% CI = −0.11 to 0.27; ability: mean = 4.00 [SD = 0.75], 95% CI = −0.12 to 0.28), suggesting that momentum and buy-in were sustained (Tab. 2, Suppl. Appendix 2). Of the 9 survey items included within the category assessing the Division’s commitment to change, means all fell within the “Agree” or “Strongly Agree” ranges, but the lowest scoring item and that with the largest variance was, “The Division creates an environment where everyone has equal opportunities to advance” (initial: mean = 3.71 [SD = 1.00]; follow-up: mean = 3.81 [SD = 1.03]). Taking a deeper look at this item, the majority of respondents expressed agreement with this statement, and from initial to follow-up, 10% of respondents moved from a neutral response to agreement. The number of respondents who expressed disagreement (12%), however, did not change. This suggests some success in this area, but finding additional concrete actions to ensure everyone in the Division has equal opportunity to advance must continue to be a priority of this work.

After 1 year, participants felt more confident (95% CI = 0.18 to 0.76) and comfortable (95% CI = 0.14 to 0.72) engaging in content related to EDI and brought up these concepts more often, embedding them within teaching, research, and service (95% CI = 0.28 to 0.92). Participants also were more confident they could identify (95% CI = 0.20 to 0.74), address (95% CI = 0.45 to 1.03), and resolve (95% CI = 0.18 to 0.74) conflicts related to bias, microaggressions, or cultural insensitivity. Faculty and staff also reported risking their reputation to talk about race more often (95% CI = 0.15 to 0.57).

Regarding identifying and addressing racism at the individual/interpersonal, institutional, and structural levels, the survey results revealed that after 1 year of this work, participants felt more equipped to both identify and address racism at the individual/interpersonal level (identify: 95% CI = 0.07 to 0.55; address: 95% CI = 0.16 to 0.66) and at the institutional level (identify: 95% CI = 0.09 to 0.59; address: 95% CI = 0.09 to 0.67). These improvements were not observed, however, when faculty and staff were asked about structural racism (identify: 95% CI = −0.07 to 0.41; address: 95% CI = −0.04 to 0.54). Consistently, respondents expressed greater confidence in identifying racism compared with addressing racism. Identification involves cognitive processes individuals engage in by themselves through attention, awareness, and reflection. Although identification of racism can still cause discomfort, it may be an easier process than addressing racism, which requires some type of action between multiple individuals or within an institution or system. Taking action can make the individual vulnerable to the commentary, response, or critique of peers or students. Furthermore, identifying racism likely must precede addressing racism as one must be able to identify the problem before one can address it appropriately.21 It may, therefore, be expected that confidence in identifying racism will always exceed confidence in addressing racism. Fortunately, the initiatives pursued through the Comprehensive Anti-Racism Plan increased confidence in both of these processes at the individual/interpersonal and at the institutional levels. This increase in confidence can be attributed in part to the success of the multiple speakers, workshops, and trainings the community engaged with, which focused not only on education but also on building skills to address racism. The second observation from these data is that confidence in identifying and addressing racism decreases as the levels become more complex. Structural racism in particular, in the context of an academic physical therapy program, involves the interacting systems of health care, higher education, and capitalism among others.22 Future trainings should emphasize ways faculty and staff can participate in addressing racism at the more complex institutional and structural levels to improve confidence and ability.

Discussion

This administrative case report provides 1 example of how an academic physical therapy program integrated explicit anti-racist action and expanded its EDI initiatives. Prior to the development and implementation of the Comprehensive Anti-Racism Plan, the Division had begun work in the areas of holistic admissions, the development of a diversity committee, and the development of an undergraduate to Doctor of Physical Therapy pathway program partnering with a Historically Black University. These initiatives were all valuable to the Division’s mission of creating a more racially diverse student cohort; however, they were not sufficient to achieve racial equity across the Division. After the first year of this work, significant structural organizational changes were made, and several successful initiatives were implemented including updating faculty merit review to include EDI, the development of a bias reporting mechanism, faculty development activities, resources, and groups around EDI and anti-racism, and expanded efforts to recruit a more diverse class. In addition, improvements in faculty and staff confidence in their ability to identify and address racism, bias, and microaggressions were observed.

A key factor in the success of developing and implementing the plan was the significant support and engagement by faculty and staff, with 95% agreeing or strongly agreeing that it is valuable to examine and discuss the impacts of race on the work of the Division (mean = 4.47 [SD = 0.86]). This support and engagement was likely a result of concurrent pursuits of listening to the Division community humbly, educating ourselves about others’ lived experiences and about systems that uphold inequity, building consensus with all Division members, and allowing a range of opportunities to engage and lead. A second factor in this success was the openness to the shifting needs of the Division and changing priorities of the University. The plan was and is a work-in-progress, requiring iterations each year as needs are stated by Division members, more is understood about the Division, and Division members feel equipped to address particular issues. As momentum mounted in the summer of 2020, Division leadership made the conscious choice to begin initiatives as soon as enough preparation had been done for them to be viable rather than a long planning process with the goal for perfection. In retrospect, this was the beginning of rejecting “perfectionism” (an oppressive cultural characteristic)23 as a pillar of the journey to becoming an anti-racist institution. Moving forward, the DARIC Council leadership is looking to move from revising the plan annually to developing a 3- to 5-year strategic plan that is integrated into the Division’s strategic plan. The intention of a longer term plan is to further embed this work into all Division operations and sustain momentum to achieve longer term goals.

The many successes in this process also came with several challenges, including a fear of saying or doing the wrong thing by Division members new to discussing racism and a feeling of burden in addressing this in the middle of a pandemic. Keys to addressing these challenges were building a culture of humility and acceptance and framing anti-racism as a new lens through which to view the work of the Division, not a separate job or task list. Lastly, building consensus around the plan as it was being shaped was an important objective, but it was understood that consensus did not necessarily mean unanimity. Indeed, there were some faculty and staff in the Division who felt the plan went too far and others who believed it did not go far enough. In our view, consensus was not to be thought of as a state of general agreement by most or all of the faculty and staff. Rather, consensus was viewed as a dynamic process of change in our collective understanding of structural racism and its impact on our community as well as on health care and higher education as larger entities. This evolution of our community did not proceed in lockstep; on the contrary, individuals moved at different rates in their development, a process that continues to this day. The important aspect of having consensus as a primary objective was that it continuously encouraged the leadership of the Division to provide multiple opportunities for engagement rather than simply developing the plan using a top-down approach.

Conclusion

Academic programs are in a unique position to aid health care systems in facing the recalcitrant problem of racism, which continues to be a significant cause of health disparities in the United States. In order for the physical therapy profession to make progress in confronting racism in health care systems, EDI and anti-racism work need to be seen as an imperative for excellence. As with any valued work in academic programs, infrastructure to address these issues will need to be built, comprehensive and thoughtful assessments that lead to the development of measurable goals will have to be administered, and the work of faculty and staff to move these goals forward will need to be valued and rewarded as part of the merit review process. Academic programs should look to create alignment on these issues with their parent universities, professional organizations, and accreditation bodies, as well as with organizations specifically devoted to advancing equity and anti-racism in higher education.

In conclusion, the vision of the physical therapy profession is to transform society. This will require dismantling the racism and inequities that have plagued society for generations. To accomplish this, the profession must start inside its organizations and institutions. This article describes the experience of 1 organization in confronting that challenge.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the many members of our USC Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy who have aided in the development, implementation, and iteration of our comprehensive anti-racism plan over the past 2 years, with special acknowledgement to Kristan Leech, PT, DPT, PhD; Kathyrn L. Havens, PhD; and Kari S. Kretch, PT, DPT, PhD, faculty members whose insight aided in the improvement of this manuscript. We also acknowledge and thank Ben Hecht, Ellen Ward, Hafizah Omar, and Nadia Owusu of Living Cities for allowing us to use items from their Staff Racial Equity & Inclusion Competency Survey.

Contributor Information

Ndidiamaka D Matthews, Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA.

K Michael Rowley, Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA; Department of Kinesiology, California State University East Bay, Hayward, California, USA.

Stacey C Dusing, Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Libby Krause, Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Noriko Yamaguchi, Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA.

James Gordon, Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Author Contributions

Concept/idea/research design: N.D. Matthews, K.M. Rowley, S.C. Dusing, L. Krause, N. Yamaguchi, J. Gordon

Writing: N.D. Matthews, K.M. Rowley, S.C. Dusing, L. Krause, N. Yamaguchi, J. Gordon

Data collection: N.D. Matthews, K.M. Rowley, J. Gordon

Data analysis: N.D. Matthews, K.M. Rowley, J. Gordon

Project management: N.D. Matthews

Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): K.M. Rowley, L. Krause

Funding

This project was supported by grants from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) of the US National Institutes of Health (UL1TR001855 and UL1TR000130). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Ethics Approval

The IRB Approval Number is UP-20-00994.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data were generated at the University of Southern California in the Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Disclosures

The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reported no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Capers Q, Clinchot D, McDougle L, Greenwald A. Implicit racial bias in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2017;92:365–369. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gasman M. Doing the Right Thing: How Colleges and Universities Can Undo Systemic Racism in Faculty Hiring. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ginther DK, Schaffer WT, Schnell J, et al. Race, ethnicity, and NIH research awards. Science. 2011;333:1015–1019. 10.1126/science.1196783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mahajan S, Caraballo C, Lu Y, et al. Trends in differences in health status and health care access and affordability by race and ethnicity in the United States, 1999-2018. JAMA. 2021;326:637–648. 10.1001/jama.2021.9907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, et al. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for Black and white patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1231–1238. 10.1007/s11606-007-0258-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The History of African Americans and Organized Medicine. American Medical Association. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/ama-history/history-african-americans-and-organized-medicine.

- 7. Feagin J, Bennefield Z. Systemic racism and U.S. healthcare. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:7–14. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mate KS, Wyatt R. Health equity must be a strategic priority. NEJM Catalyst. 2017;3:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Salles A, Arora VM, Mitchell KA. Everyone must address anti-Black racism in health care: steps for non-Black health care professionals to take. JAMA. 2021;326:601–602. 10.1001/jama.2021.11650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wedekind L, Noe A, Mokaya J, et al. Equity for excellence in academic institutions: a manifesto for change. Wellcome Open Res. 2021;6:142. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16861.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moen R, Norman C. The history of the PDCA cycle. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the 7th ANQ Congress; September 17, 2009; Tokyo. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Safir S, Dugan J. Street Data: A Next-Generation Model for Equity, Pedagogy, and School Transformation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peeples L. What the data say about police brutality and racial bias- and which reforms might work. Nature. 2020;583:22–24. 10.1038/d41586-020-01846-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Joseph TD, Hirshfield LE. “Why don’t you get somebody new to do it?” Race and cultural taxation in the academy. Ethn Racial Stud. 2010;34:121–141. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cleveland R, Sailes J, Gilliam E, Watts J. A theoretical focus on cultural taxation: who pays for it in higher education. Adv Soc Sci Res J. 2018;5:95–98. 10.14738/assrj.510.5293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Survey: Assessing Our Staff’s Racial Equity & Inclusion Competency. Living Cities. 2018. Accessed September 1, 2020. https://livingcities.org/resources/survey-assessing-our-staffs-racial-equity-inclusion-competency/.

- 17.Home page. Government Alliance on Race and Equity. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://www.racialequityalliance.org/.

- 18.Home page. D5 Coalition. Accessed October 2, 2022. https://www.d5coalition.org/.

- 19.Giving InSight. Health & Environmental Funders Network. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://www.hefn.org/connect/blog/more_is_required_of_us5.

- 20. Association of American Medical Colleges . Diversity, Inclusion Culture, and Equity (DICE) Inventory User Guide. Washington, DC: AAMC; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gordon SP. Making meaning of whiteness: a pedagogical approach for multicultural education. J Phys Ther Educ. 2005;19:21–27. 10.1097/00001416-200501000-00004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Matthews ND, Rowley KM, Dusing SC, Krause L, Yamaguchi N, Gordon J. Beyond a statement of support: changing the culture of equity, diversity, and inclusion in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2021;101:pzab 212. 10.1093/ptj/pzab212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Okun, T. White Supremacy Culture. Accessed October 14, 2022 https://www.whitesupremacyculture.info/.

- 24.Being Anti-Racist. Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Accessed January 27, 2021. https://nmaahc.si.edu/learn/talking-about-race/topics/being-antiracist.

- 25.Racial Equity Tools Glossary. Racial Equity Tools. Accessed January 27, 2021. https://www.racialequitytools.org/glossary.

- 26. Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretical framework and a Gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1212–1215. 10.2105/AJPH.90.8.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Armitage P, Berry G. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 3rd ed. London: Blackwell; 1994: 108–109. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data were generated at the University of Southern California in the Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.