Abstract

Snake envenomation is a neglected tropical disease. In Brazil, the Bothrops genus is responsible for about 86% of snakebite accidents. Despite extensive evidence of the cytotoxicity of snake venoms, the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved are not fully understood, especially regarding the effects on cell cycle progression and cytoskeleton organization. Traditionally, the effectiveness and quality control tests of venoms and antivenoms are assessed by in vivo assays. Despite this, there is a rising effort to develop surrogate in vitro models according to the 3R principle (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement). In this study, we treated rat liver cells (BRL-3A) with venoms from five Bothrops species (B. jararaca, B. jararacussu, B. moojeni, B. alternatus, and B. neuwiedi) and analyzed cell viability and IC50 by MTT assay, cell cycle phases distribution by flow cytometry, and morphology and cytoskeleton alterations by immunofluorescence. In addition, we evaluated the correlation between IC50 and the enzymatic and biological activities of each venom. Our results indicated that Bothrops spp. venoms decreased the cell viability of rat liver BRL-3A cells. The rank order of potency was B. jararacussu > B. moojeni > B. alternatus > B. jararaca > B. neuwiedi. The mechanisms of cytotoxicity were related to microtubules and actin network disruption, but not to cell cycle arrest. No clear correlation was found between the IC50 and retrieved literature data of in vitro enzymatic and in vivo biological activities. This work contributed to understanding cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the Bothrops spp. venom cytotoxicity, which can help to improve envenomation treatment, as well as disclose potential therapeutic properties of snake venoms.

Keywords: Bothrops, Venom, Cell culture, Cytotoxicity, Cytoskeleton, Cell cycle, 3R principle

1. Introduction

Snakebites are a problem of global concern, especially in tropical and developing countries [1], due to their potential for lethality. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), about 4.5–5.4 million people are bitten by snakes annually: with 1.8–2.7 million developing clinical illnesses and 81,000 to 138,000 dying from complications resulting from snakebite envenoming [2]. Based on this, the WHO classified snakebites as a neglected tropical disease in 2017 and established a plan to reduce 50% of envenomation-related deaths and disabilities by 2030 [3].

Envenomation by the Bothrops genus is of utmost medical importance in Brazil, accounting for nearly 86% of snakebites [4]. Local symptoms include edema, hemorrhage, inflammation, and necrosis, while systemic effects include pain, coagulopathy shock, and acute renal failure [5]. The most abundant components of Bothrops venoms comprise snake venom metalloproteinases (SVMPs), snake venom serine proteases (SVSPs), phospholipases (PLAs), l-amino acid oxidases (LAAOs), and lectins (LECs) [6,7].

Nevertheless, the diversity of bothropic venom composition implies distinct toxic activities [7,8] associated with local and systemic envenomation effects, which are not neutralized efficiently by current serum therapy [9]. Despite the extensive evidence of snake venom's cytotoxicity [10], the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms are not fully understood, especially regarding the effects on cell cycle progression and cytoskeleton organization.

The cell cycle progression, regulated by checkpoint proteins, consists of five phases, designated G0 (gap 0), G1 (gap 1), S (DNA synthesis), G2 (gap 2), and M (mitosis). The checkpoint proteins monitor not only the integrity of cellular components but also the fidelity of DNA synthesis [11]. The dysregulation of these checkpoints is an effective way to induce cell cycle arrest and prevent cell proliferation used by several cytotoxic agents [12]. Arresting in the G0/G1 or G2/M phases could lead to cell inhibition, ultimately resulting in cell death [13].

The cytoskeleton, composed of microtubules, actin microfilaments, and intermediate filaments, plays a crucial role in various cellular functions. Microtubules, made of α and β-tubulin dimers, are involved in mitotic spindle assembly, intracellular transport, organelle positioning, cell-cell signaling, motility, and cell morphology maintenance [14]. Actin microfilaments are F-actin-based linear double helical structures that participate in cell morphogenesis, membrane dynamics, cell mechanics, gene transcription, and protein translation [14]. Many cytotoxic compounds can bind to microtubules, modifying their polymerization and dynamics, leading to mitosis blocking and cell death [15]; a disorganized actin network is related to loss of cell adhesion, migration, and metastasis [16], actin machinery is closely involved in the programmed cell death [17], and actin cytoskeleton also plays an essential role in virus infection [18] and immune response [19].

Traditionally, the effectiveness and quality control tests of venoms and antivenoms are assessed by in vivo assays [20]. Despite this, there is a rising effort to develop surrogate in vitro models [21] according to the 3R principle (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) [22,23]. The Replacement principle encourages the development of alternative methods, such as in vitro or in silico tests, to reduce reliance on animal testing. The Reduction principle aims to minimize the number of animals in the experimental designs, enhancing techniques to avoid waste and integrating in vivo with in vitro and ex vivo techniques at different research stages. The Refinement principle values the animal's welfare, seeking to avoid unnecessary risks and reduce suffering during experimental conditions [24].

In this study, we investigated the effects of five Bothrops spp. venoms on cell viability, distribution of cell cycle phases, cell morphology, and cytoskeleton organization. Besides, we evaluated the correlation between the venom concentration able to reduce 50% of cell viability (IC50) and in vitro enzymatic or in vivo biological activities to propose this cell culture model as an alternative method that complies with the principle of the 3Rs.

Our results indicated that Bothrops spp. venoms decreased the cell viability of rat liver BRL-3A cells. The rank order of potency was B. jararacussu > B. moojeni > B. alternatus > B. jararaca > B. neuwiedi. The mechanisms of cytotoxicity seem to be related to microtubules and actin network disruption, but not to cell cycle arrest. No clear correlation was found between the IC50 and enzymatic or biological activities.

2. Methods

2.1. Bothrops spp. venoms

We used the venoms from five Bothrops species (B. jararaca, B. jararacussu, B. moojeni, B. alternatus, and B. neuwiedi). Each venom was collected separately from specimens maintained at the Laboratory of Herpetology of Butantan Institute, pooled, snap-frozen, lyophilized, and stored at −20 °C. Before use, each venom was reconstituted in sterile phosphate saline buffer at 1 mg/mL, sterilized by 0.22 μm syringe filtration, and stored at −20 °C in aliquots, which were thawed and diluted just before use. The same venom lot (01/19-1) was used for all the experiments.

2.2. Cell culture

Human retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPE-1, CRL-4000 ATCC, USA) and rat immortalized liver cells (BRL-3A, BCRJ, Brazil) were cultivated in DMEM-F12 culture medium (GIBCO, USA) with fetal bovine serum supplementation (10%) and antibiotics penicillin (100 IU/mL) and streptomycin (0.1 mg/mL) at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

2.3. Treatment of cells with Bothrops spp. venoms

2.3.1. Cell viability and calculation of IC50

For cell viability assay and calculation of the IC50, 1.5 × 104 cells of RPE-1 or 5 × 103 cells of BRL-3A were seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 16 h before treatment with Bothrops spp. venoms in a DMEM-F12 medium without fetal bovine serum supplementation for 24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Each venom (1 mg/mL) was diluted to concentrations from 0.5 to 10 μg/mL in DMEM-F12 medium, and 100 μL was added to each well. DMEM-F12 alone was used as a control sample. After treatment, the medium was removed, 100 μL of the MTT solution (1.0 mg/mL) was transferred to each well and the plate was incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. The MTT solution was removed and 100 μL of DMSO was added to each well, placed at 37 °C for 5 min, and absorbance at 570 nm and 630 nm were read in BioTek's Gen5™ Data Analysis software [25]. The absorbance values at 630 nm were subtracted from the values at 570 nm and the percentage of cell viability was calculated relative to the control (set as 100%) by the mean ± SD or SEM of three independent experiments with six replicates for each sample [25]. The IC50 values were calculated using the functions drm and ED from the R package for “Analysis of Dose-Response Curves”, dcr [26]. The corresponding figure was plotted using ggplot2 [27]. Statistical analysis was performed using Dunnett's test - ANOVA.

2.3.2. Correlation of IC50 and enzymatic and biological activities of Bothrops spp. venoms

To evaluate the correlation between IC50 and the enzymatic and biological activities of each venom, we retrieved data on phospholipase A2, hyaluronidase, and proteolytic activities from Queiroz et al. (2008) [7] and hemorrhagic, necrotizing, edematogenic, coagulant, and myotoxic activities from Ferreira et al. (1992) [8]. Both works used venoms from specimens maintained at the Laboratory of Herpetology of Butantan Institute. The medium values of the lethal dose (LD50) stipulated for each venom were obtained from the technical control reports of the same venoms' lot (01/19-1) used in the experiments. In the linear regression analysis, IC50 was the dependent variable, and the venom activities were the independent variables. The correlation coefficient was calculated by Pearson's product-moment, using the cor.test function from the stats package in R base [28]. The strength of the correlation coefficient (R) was classified according to the correlation coefficient range: [0.0, 0.19] very weak; [0.20, 0.39] weak; [0.40, 0.59] moderate; [0.60, 0.79] strong; and [0.80–1] extraordinarily strong, considering significant a p-value <0.05.

2.3.3. Cell cycle phases distribution

For analysis of the cell cycle phases distribution, BRL-3A cells (3.1 × 104 cells/well) were plated in 6-well plates, incubated for 48 h, and treated with B. jararacussu 3 μg/mL, B. moojeni 4 μg/mL, B. alternatus 5 μg/mL, B. jararaca 5.5 μg/mL or B. neuwiedi 7.5 μg/mL venoms in DMEM-F12 medium without fetal bovine serum supplementation for 24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. DMEM-F12 alone was used as a control sample. Then, cells were fixed with cold 75% methanol at room temperature for 1 h, followed by washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBSA). DNA was stained with propidium iodide (10 μg/mL) diluted in PBSA containing RNase (1 mg/mL) and incubated at 4 °C for 1 h. Analysis was performed on a flow cytometer (GUAVA EasyCyte Plus, MA, USA). Because the number of cells available after treatment with IC50 of each venom was not sufficient to obtain reliable results, we set to decrease 1 μg/mL from IC50 values of each venom for the cell cycle and cell morphology assays.

2.3.4. Cell morphology and nuclear and cytoskeleton analyses

Nuclear and cell morphology were analyzed by photographed images in bright field microscopy with a 20x objective (Life Technologies EVOS XL Digital Imaging System) and by immunofluorescent staining. BRL-3A cells were cultured on coverslips in 35 mm plates and treated with each Bothrops spp. venoms for 24 h, as described before. Cells were fixed with formaldehyde (3.7%) for 30 min and permeabilized with Triton X-100 (0.5%) for 30 min [29]. The samples were washed with PBSA, immunostained with primary monoclonal antibodies produced in mice, anti-α-tubulin (1:50) and anti-β-tubulin (1:50) (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), and incubated overnight at room temperature in the dark. Corresponding secondary antibody anti-mouse IgG (H + L), F(ab')2 Fragment (Alexa Fluor® 488 Conjugate) (1:50) (Cell Signaling Technology®, MA, USA), was incubated for 2 h. Actin microfilaments were labeled with phalloidin conjugated to Alexa Fluor® 555 (1:20) (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) for 2 h. Nuclei were labeled with DAPI (1:100) (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), and the coverslips were mounted with Vecta-Shield (Vector Laboratories, CA, USA). Analyses were performed on the LionHeart FX fluorescence microscope (Biotek, VT, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Cell viability and IC50

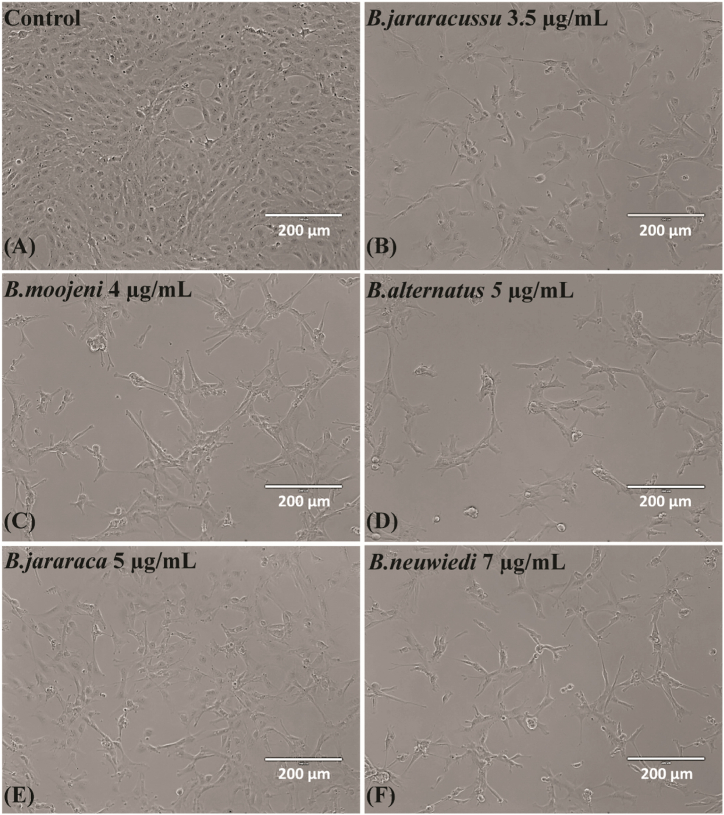

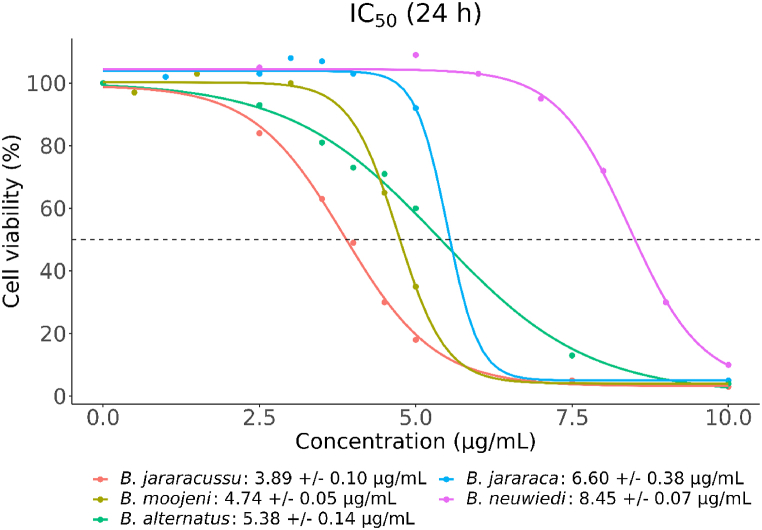

At first, we compared the effect of B. jararaca venom on the cell viability in two immortalized cell lines: human retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPE-1) and rat liver cells (BRL-3A). B. jararaca crude venom caused morphological alterations and cytotoxicity in both cell lines (Figs. 1 and 4, S1, and S2 - Supplementary Material). The cell density of the RPE-1 line gradually decreased, forming clusters above 75 μg/mL (Fig. S1). These results were supported by a concentration-dependent decrease in cell viability, with 20 μg/mL of venom causing a significant reduction of RPE-1 cell viability (58.7 ± 6.2%), which smoothly diminished to 28.1 ± 9.1% at 75 μg/mL until 9.3 ± 2.2% at 150 μg/mL (Fig. S2). In comparison, BRL-3A cells presented morphological alterations from 5 μg/mL (Fig. 4E), with a drastic decrease in cell viability at 10 μg/mL (5.2 ± 0.3%) (Fig. 1D). The IC50 for RPE-1 cells was 31.7 ± 14.1 μg/mL, and the IC50 for BRL-3A cells was 6.6 ± 0.4 μg/mL (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Cell viability measured by MTT assay of BRL-3A cells treated with B. jararacussu (A), B. moojeni (B), B. alternatus (C), B. jararaca (D), or B. neuwiedi (E) venoms from 0.5 μg/mL to 10 μg/mL for 24 h. Data were expressed by mean ± SEM of the relative percentage of the control of three independent experiments with four replicates for each sample. The Dunnett - ANOVA test performed statistical analysis for multiple comparisons vs. control. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

Fig. 4.

Cell morphology after treatment of BRL-3A cells with Control (A), B. jararacussu 3.5 μg/mL (B), B. moojeni 4 μg/mL (C), B. alternatus 5 μg/mL (D), B. jararaca 5 μg/mL (E), or B. neuwiedi 7 μg/mL (F) for 24 h. Bar = 200 μm.

Fig. 2.

Venom concentrations able to reduce 50% of cell viability (IC50) of BRL-3A cells treated with B. jararacussu, B. moojeni, B. alternatus, B. jararaca, or B. neuwiedi, from 0.5 μg/mL to 10 μg/mL, for 24 h. Cell viability was measured by MTT assay. Data are expressed by the mean of three independent experiments with six replicates for each sample [25]. The IC50 values were calculated using the functions drm and ED from the dcr package [26] and were plotted using ggplot2 [27].

Given that the IC50 of RPE-1 cells was much higher than BRL-3A cells and most of the in vivo tests were first conducted in rats or mice, we selected BRL-3A rat liver cells for further investigation. Treatment of BRL-3A cells with 0.5–10 μg/mL of five Bothrops spp. venoms affected cell viability. In the MTT assay, all five venoms presented less than 10% of cell viability at 10 μg/mL. B. jararacussu and B. alternatus venoms induced a concentration-dependent decrease starting from 2.5 μg/mL (Fig. 1A, C), while for B moojeni and B. neuwiedi, the decrease in cell viability started from 4.5 μg/mL and 8 μg/mL respectively (Fig. 1B, E). B. jararaca venom presented an abrupt decrease in cell viability from 92.0 ± 4.5% with 5 μg/mL to 5.2 ± 0.3% with 10 μg/mL (Fig. 1D).

BRL-3A cell line presented the following IC50 for each venom: B. jararacussu (3.9 ± 0.1 μg/mL), B. moojeni (4.7 ± 0.05 μg/mL), B. alternatus (5.4 ± 0.1 μg/mL), B. jararaca (6.6 ± 0.4 μg/mL), and B. neuwiedi (8.4 ± 0.1 μg/mL) (Fig. 2).

One of the limitations of this experiment is that the cell viability evaluated by MTT assay is an indirect measurement of an integrated set of enzyme activities that are related in many ways to cell metabolism rather than a direct cell count [30].

3.2. Correlation of IC50 and enzymatic and biological activities of Bothrops spp. venoms

To evaluate if toxicity analysis in BRL-3A cell culture might be eligible as a surrogate in vitro model according to the 3R principle, we calculated the correlation coefficient R of the IC50 obtained in cell viability assay with previous in vitro enzymatic activities, the medium lethal dose (LD50), and biological activities in mice [7]. We plotted the linear regression of each comparison and calculated the correlation coefficient R (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficient between IC50 X enzymatic activities and biological activities of five Bothrops spp. venoms.

| Venom activity | R | statistic | p.value | conf.low | conf.high |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lethal | |||||

| LD50 a (mg/kg) | −0.78 | −2.13 | 0.12 | −0.98 | 0.34 |

| LD50-Lot (μg/animal) | −0.73 | −1.84 | 0.16 | −0.98 | 0.43 |

| Enzymatic | |||||

| PLA2 a (nmol/min/mg) | −0.31 | −0.56 | 0.61 | −0.94 | 0.79 |

| Hyal a (UTR/mg) | 0.27 | 0.49 | 0.66 | −0.80 | 0.93 |

| Prot a (U/μg) | 0.27 | 0.48 | 0.66 | −0.80 | 0.93 |

| Biological | |||||

| Hemo b (mm2/μg) | 0.22 | 0.39 | 0.72 | −0.82 | 0.92 |

| Edema b (mg/μg) | 0.41 | 0.78 | 0.49 | −0.74 | 0.95 |

| Necro b (mm2/μg) | 0.84 | 2.70 | 0.07 | −0.16 | 0.99 |

| Myo b (U/mg) | −0.34 | −0.54 | 0.63 | −0.94 | 0.77 |

| Coag b (mg-1) | 0.75 | 1.97 | 0.14 | −0.39 | 0.98 |

LD50: medium lethal dose. LD50 Lot: Data from quality control report of extracted venoms (lot Bja 01/19-1) Butantan Institute. PLA2: phospholipase A2, HYAL: hyaluronidase, Prot: proteolytic, Hemo: hemorrhagic, Edema: edematogenic, Necro: necrotizing, Myo: myotoxic, Coag: coagulant. R: correlation coefficient; conf.low: low limit of the confidence interval; conf.high: high limit of the confidence interval. a Data from Queiroz et al., 2008 [7] b Data from Ferreira et al., 1992 [8].

No clear correlation could be calculated between the IC50 values and LD50 values retrieved from the Lot report (−0.73) and Queiroz et al., 2008 (−0.78). Regarding enzymatic activities, a moderate correlation between IC50 and hyaluronidase activity (0.27), or proteolytic activity (0.27) was found. The correlation of IC50 values with biological activity values was very weak for hemorrhagic (0.22), myotoxic (−0.34), edematogenic (0.41), and coagulant (0.75) activities considering the p-value >0.05. The correlation coefficient R for necrotizing activity was 0.84 (p-value = 0.07), which suggests a potential correlation with IC50. However, further standardized experiments with a higher number of replicates are required for the establishment of a statistically significant correlation.

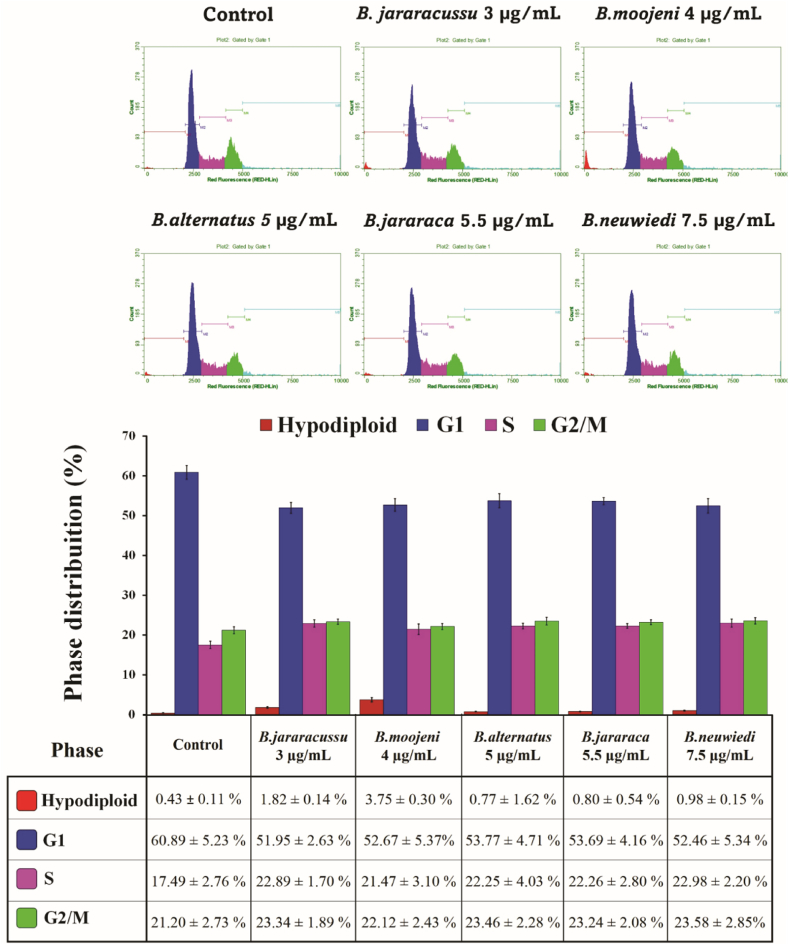

3.3. Cell cycle phases distribution

To deeply investigate the mechanism of action of cytotoxicity induced by each venom, we analyzed the cell cycle phases distribution of treated BRL-3A cells (Fig. 3). All the venoms’ treatments resulted in quite a similar cell distribution. Compared with the control, the hypodiploid, S, and G2/M phases presented a slight increase with a decrease in the G1 phase. The frequency of hypertetraploid corresponds to cells with a DNA ploidy of more than 4 N, which do not belong to any specific cell cycle phase. Therefore, they were not considered to calculate the frequencies of the G1, S, and G2/M populations (Fig. 3). However, the inclusion of hypertetraploid cells in the calculation resulted in a frequency ranging from 3.52 ± 0.55% to 3.86 ± 0.70% (Fig. S4). Since this assay is based on the DNA staining according to the different cell ploidy along the cell cycle phases, it was not possible to determine if the cells continue cycling or can proliferate.

Fig. 3.

Flow cytometry distribution of cell cycle phases of BRL-3A cells treated with B. jararacussu 3 μg/mL, B. moojeni 4 μg/mL, B. alternatus 5 μg/mL, B. jararaca 5.5 μg/mL or B. neuwiedi 7.5 μg/mL for 24 h. Hypertetraploid cells were not included in the construction of the histogram. Data were expressed by mean ± SEM of the relative percentage of the control of three independent experiments with two replicates for each sample.

3.4. Cell morphology and nuclear and cytoskeleton analyses

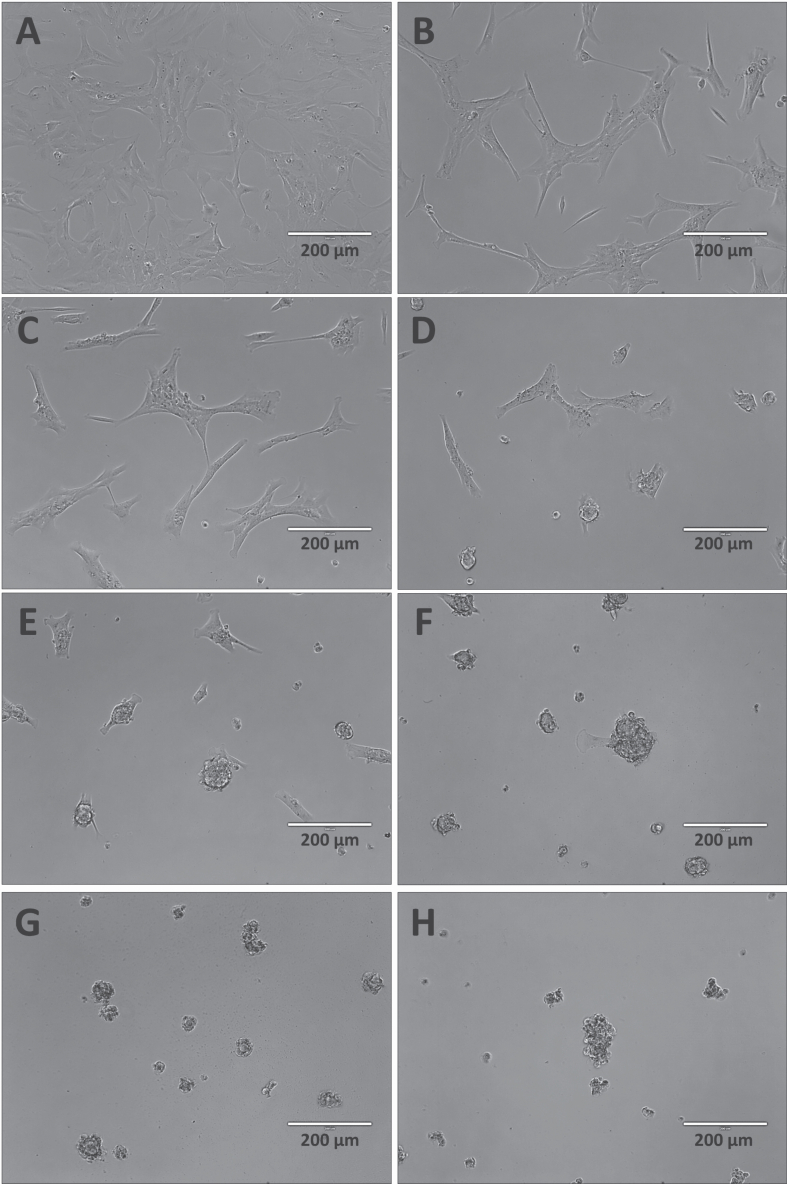

Analysis of bright field images of BRL-3A cells acquired in the cell viability assay showed that all the venoms caused a decrease in cell density and altered cell morphology (Fig. 4A–F). These results prompted us to verify the presence of alterations in the nucleus and cytoskeleton by immunofluorescent staining of microtubules and actin microfilaments (Figs. S3 and 5A–F).

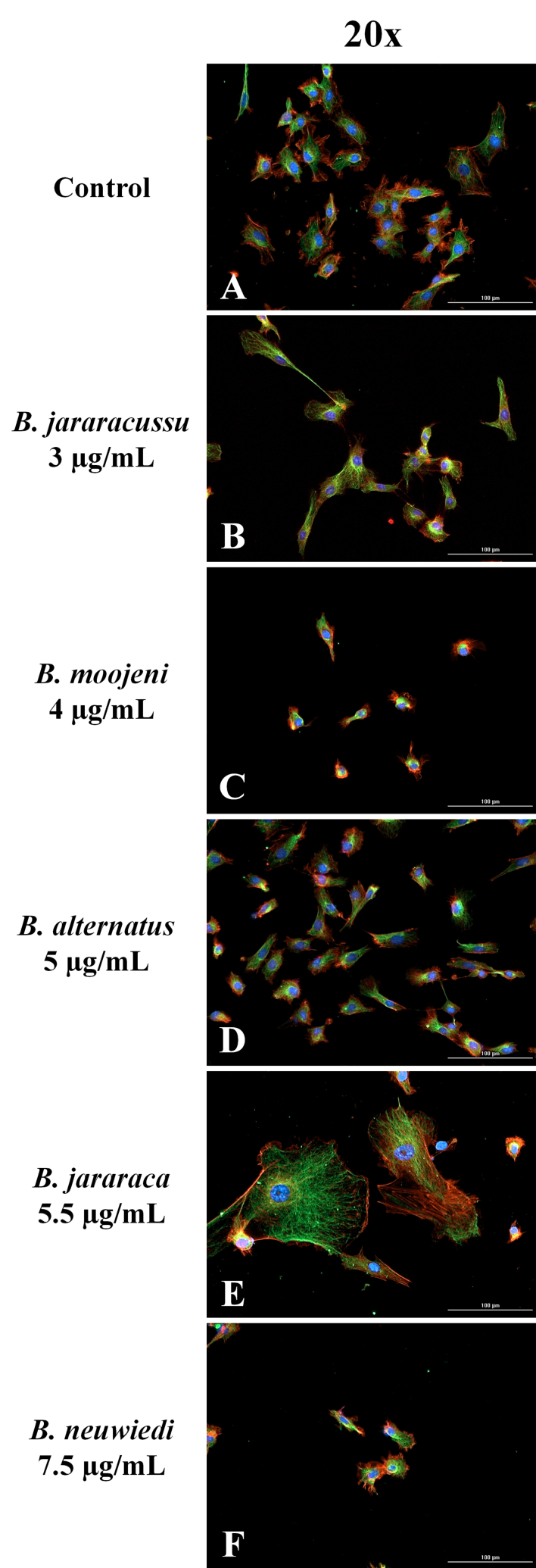

Fig. 5.

Fluorescence microscopy images of BRL-3A cytoskeleton. Images of control (A) and after 24 h treatment of BRL-3A with B. jararacussu 3 μg/mL (B), B. moojeni 4 μg/mL (C), B. alternatus 5 μg/mL (D), B. jararaca 5.5 μg/mL (E) or B. neuwiedi 7.5 μg/mL (F), submitted to immunofluorescence reaction with antibodies against α and β-tubulin (microtubules) plus anti-mouse secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (green). Microfilaments of F-actin were stained by phalloidin - Alexa Fluor 555 (red) and nuclei by DAPI (blue). Bar = 30 μm. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

In the panel of Fig. 5A–F, we showed representative fluorescent images with the nucleus in blue, α and β-tubulins of the microtubules in green, and F-actin microfilaments in red. No significant alteration in the nucleus morphology was observed (Fig. S3). The effect of cell shrinkage induced by B. moojeni (Fig. 5C, C1, C2) and B. neuwiedi (Fig. 5F, F1, F2) venoms was similar. B. jararacussu′s venom induced spindle-shaped cells (Fig. 5B, B1, B2). On the contrary, B alternatus venom presented the least affected cell morphology (Fig. 5D, D1, D2). Oddly, B. jararaca venom induced the formation of giant cells (Fig. 5E, E1, E2).

4. Discussion

The cytotoxicity of snake venoms has long been known [31]. However, different cell lines exhibit significant variations in venom susceptibility. We selected the BRL-3A cell line from rat liver to assess the toxicities of Bothrops spp. venoms because it is well characterized in vitro [32]. Our results showed that BRL-3A cells were more susceptible to B. jararaca venom than RPE-1 cells, with an IC50 of 6.6 ± 0.4 μg/mL, compared to RPE-1 (31.7 ± 14.1 μg/mL). Other studies showed an IC50 of 11.79 μg/mL in Vero cells [33] and an IC50 of 9.96 μg/mL in MGSO-3 cells [34], suggesting that the BRL-3A cell line, a non-tumoral rat liver cell, is more susceptible than the human mammary tumor cell line MGSO-3 and the Vero monkey kidney cell line.

In MGSO-3 cells, the rank order of potency of bothropic venoms and IC50 (μg/mL) are B. neuwiedi (4.07) > B. jararacussu (4.24) > B. moojeni (4.66) > B. jararaca (9.96)> B. alternatus (12.42) [34]. Our results showed the following rank order of potency and IC50 (μg/mL) for BRL-3A cells: B. jararacussu (3.9 ± 0.1 μg/mL), B. moojeni (4.7 ± 0.05 μg/mL), B. alternatus (5.4 ± 0.1 μg/mL), B. jararaca (6.6 ± 0.4 μg/mL), and B. neuwiedi (8.4 ± 0.1 μg/mL) (Fig. 2). Comparing the rank order of IC50 of the MGSO-3 and BRL-3A cell lines, it is interesting to note that the IC50 of B. neuwiedi was the lowest for the MGSO-3 but highest for the BRL-3A line. For other venoms, the order of IC50 was almost the same. However, comparisons of IC50 and LD50 values of each venom from the same lot used in all the experiments showed a different susceptibility pattern. The rank order of potency and LD50 (μg/animal) was B. neuwiedi (31.26) > B. jararaca (48.71) > B. jararacussu (82.38) > B. alternatus (126.38) > B. moojeni (131.08).

Even if in vivo testing cannot be completely replaced, cell culture offers an alternative to the widespread use of animal models. Although BRL-3A cell culture is a well-characterized model for in vitro toxicity assays [35], the liver is not an organ usually affected by envenomation, which could explain the lack of correlation between IC50 and enzymatic or biological activities of Bothrops spp. venoms, especially with LD50 (Table 1). Despite this, other cell lines and viability assays have already been proposed as a surrogate in vitro model to assess the toxic effect of venoms and antivenoms [36]. In the human primary breast cancer MGSO-3 cell line, the IC50 of Bothrops spp. venoms, measured by neutral red incorporation, showed no correlation with LD50 but presented positive correlations with LAAO activity, necrosis, and edema [34]. On the other hand, a positive correlation was found in Vero cells between IC50 and LD50 of some species of the Bothrops genus [37]. Vero cells and AlamarBlue® reagent have been proposed as viable alternatives for determining bothropic antivenom potency [33]. In addition to cell culture, alternative in vitro assays have also been under development, such as the Artemia salina bioassay as a potential surrogate test of dermonecrosis in mice [38] and embryonated eggs to assess antivenom potency [39].

For an effective establishment of any surrogate model for in vivo assays, the inherent complexity of venoms should be considered, their inter and intraspecies differences [40], the need for a strong correlation between in vitro and in vivo tests, and the intrinsic variation of each in vitro model. Even considering the requirement of systematic correlation analysis with a high number of replicates, cell culture with viability assays still represents a valuable alternative to pursue the reduction and refinement of animal use according to the 3R principle.

Snake venoms are a complex mixture of molecules, including snake venom metalloproteinases (SVMPs), snake venom serine proteases (SVSPs), hyaluronidases (HYALs), phospholipases (PLAs), l-amino acid oxidases (LAAOs), lectins (LECs), and others [41], each with a unique mechanism of action that reflects the diversity of biological effects related to the envenomation clinical manifestations [7,8].

In general, SVMPs are associated with hemorrhage due to direct action on specific components of the microvasculature [42], which contributes significantly to envenomation lethality [5]. SVSPs are toxins that affect platelet aggregation, several factors of the coagulation cascade, and fibrinolytic and kallikrein-kinin systems activity, which have been associated with the hemostatic disorders of envenomation [43]. PLAs hydrolyze membrane phospholipids, generating arachidonic acid, the precursor of leukotrienes and prostaglandins, involved in numerous homeostatic biological functions, vascular permeability, and inflammation [44]. LAAOs exert actions on platelet aggregation, induction of apoptosis, hemorrhage, and cytotoxicity [45]. LECs are haemotoxic, and can be anticoagulant, platelet aggregation inhibitors, or platelet aggregation agonists [46].

Besides systemic effects, envenomation by bothropic venoms induces several local damages, such as edema, pain, and tissue necrosis [47]. SVMPs and PLAs are central in edema [48,49] and hyperalgesic effects [50]. Myonecrosis resulted from a direct action of PLAs on the cell membrane, vascular alterations caused by SVMPs, LAAOs interaction with the cell surface and internalization, or ionic status disturbances controlled by other proteins [47,51].

Analyzing the venom's effects on cell cycle progression, we observed that the cell cycle phases distribution showed a slight increase in the number of cells in hypodiploid, S, and G2/M phases with a decrease in the G1 phase, suggesting that modulation of the cell cycle may not be the leading mechanism of action of none of the Bothrops spp. venoms.

The observed reduction of cell density (Fig. 4A–F) upon incubation with the bothropic venoms might be due to a loss of cell adhesion and probably to some type of cell death, such as necrosis, apoptosis, autophagia or others [52], which have already been proposed as mechanisms of cell death of some Bothrops spp. venoms and toxins [51,53,54]. BthTX-II, a PLA2 from B. jararacussu venom, causes no alteration in the cell cycle phase distribution of MCF10A breast epithelial cells but inhibits cell proliferation and promotes G2/M cell cycle arrest in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells [55]. Treatment of tumoral cell lines with BthTX-I, another PLA2 from B. jararacussu venom, promotes G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [56,57]. B. jararaca and B. erythromelas snake venoms promote G0/G1 cell cycle arrest, nuclear condensation, fragmentation, and induce apoptosis via mitochondrial depolarization in cervical cancer cells [53]. LAAO from B. atrox snake venom triggers apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy in normal human keratinocytes [51].

Each venom caused remarkable but distinct morphological changes through cytoskeleton disruption (Fig. 5A–F). B. jararacussu′s venom induced spindle-shaped cells with thin protrusions (Fig. 5B, B1, B2). Microtubules were more affected than actin microfilaments with B. moojeni (Fig. 5C, C1, C2) and B. neuwiedi (Fig. 5F, F1, F2) venoms, which induced cell shrinkage, microfilament aggregates and loss of cell adhesion. B. alternatus venom had a lesser impact on cell morphology (Fig. 5D, D1, D2), displaying a cytoskeleton network similar to the control cells (Fig. 5A, A1, A2). Notably, B. jararaca venom induced an abnormal microtubule organization, leading to the formation of mononucleated giant cells (Fig. 5E, E1, E2).

Histopathological analysis of muscle from chick biventer cervicis treated with different bothropic venoms shows myonecrosis, characterized by the disorganization of myofibrils with subsequent digestion of the myofilaments, condensation of nuclear chromatin with a decrease in volume and dislocation from its original position. Among the venoms tested, B. jararacussu venom caused the greatest extent of myonecrosis, followed by B. moojeni, B. neuwiedi, and B. jararaca [58]. Comparative analysis of local effects caused by B. alternatus and B. moojeni snake venoms demonstrated that the myotoxicity caused by B. moojeni venom is more prominent than B. alternatus venom [48]. Consistent with these findings, our results indicated that B. jararacussu, B. moojeni, and B. neuwiedi venoms induced a high extent of cytoskeleton alterations, followed by B. jararaca and B. alternatus (Fig. 5A–F).

Comparing the venom composition of Bothrops spp., SVMPs are found to be the most abundant component [7]. In B. jararacussu venom, PLAs equally contribute to venom composition as SVMPs followed by LAAOs, SVSPs, and LECs. In B. moojeni venom, PLAs and SVSPs are the second most abundant components, followed by LAAOs/LECs. B. neuwiedi venom presents LAAOs as the second most abundant component, followed by equal contributions of PLAs, SVSPs, and LECs. SVMPs contribute to almost 50% of the venom composition of B. alternatus, followed by LAAOs/LECs, and PLAs/SVSPs. SVMPs and SVSPs contribute equally to B. jararaca venom, followed by PLAs and LAAOs/LECs, reviewed by Mamede et al., 2020 [5].

PLA2 and its active phosphorylated form were shown to relocate at protrusions of the cell membrane involved in actin and membrane dynamics [59]. Arachidonic acid produced by PLAs induces actin polymerization and bundling, affecting cytoskeleton and cell morphology [60]. PLA2 can hydrolyze phospholipids, altering plasma membrane microviscosity, which disturbs actin dynamics and cell motility [61]. Furthermore, the permeabilization and disruption of the cell membrane integrity catalyzed by PLA2 result in an uncontrolled influx of extracellular molecules, such as Ca2+ ions, which trigger a set of events that lead to cell death [62,63]. In addition, the reaction catalyzed by PLA2s releases free fatty acids, such as arachidonic acid and lysophospholipids, which are precursors for several signaling molecules involved in inflammatory processes and pain [[64], [65], [66], [67]].

BJcuL, a lectin derived from B. jararacussu venom, induces apoptosis and actin cytoskeleton disassembly in gastric tumoral cells [54] and affects the adhesion and growth of the tumor and endothelial cells [68]. In lung cancer cells, Daboialectin, a lectin from Daboia russelli venom, produces morphological changes, including a spindle-like shape leading to loss of cell-cell contact [69]. B. moojeni crude venom disrupts the integrity of F-actin-rings in osteoclasts, which can affect their bone resorption capacity [70].

Therefore, the interspecific variation in the venom composition and toxins properties of Bothrops species [7,8] might be associated with the cytotoxicity and diverse morphological alterations observed in BRL-3A cells.

Considering the complexity of the pathogenesis of envenomation, we hypothesized further putative cellular and molecular mechanisms of action, which might be synergistically associated with the venom-induced biological effects.

The mononucleated giant cells induced by B. jararaca venom could be originated from endoreduplication of DNA, endomitosis and nuclear fusion, failures in cytokinesis [71,72], and hepatocyte hypertrophy [73]. During development, life, and aging, hepatocytes can be mononucleated or binucleated cells. However, binuclear hepatocytes assemble all condensed chromosomes from two nuclei during mitosis, producing two mononuclear hepatocytes leading to fewer binuclear hepatocytes during liver regeneration in contrast to liver development [73]. Although it is established that proliferation is an essential process in liver regeneration, it has been shown that the liver regenerates from 30% hepatectomy by hypertrophy without proliferation, and in a 70% hepatectomy, both processes equally account for liver regeneration [73]. It is hypothesized that hypertrophy might respond more efficiently to the immediate requirement to maintain homeostasis during regeneration and may be a general mechanism to compensate for the partial loss of the organ [73].

Besides, alterations in the cytoskeletal organization can also suggest that the activities of the Rho family of guanosine triphosphatases (RhoGTPases) may be altered by bothropic venoms, especially by B. jararacussu and B. neuwiedi venoms (Fig. 5B2 and 5F2).

RhoGTPases act as molecular switches that coordinate cytoskeletal organization and rearrangements by cycling between an active GTP-bound state, regulated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) [74] and an inactive GDP-bound state, stimulated by GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) [75]. In addition, guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors (GDIs) may block spontaneous activation [76].

The activation or inhibition of RhoGTPases (Rho, Rac, and Cdc42) by different stimuli affects signal transduction pathways that promote formation (actin polymerization) and organization (filament bundling) of actin filaments leading to protrusions and retractions, forming lamellipodia, filopodia, and membrane ruffling [77,78]. In addition, RhoGTPases can affect microtubule dynamics, regulating the assembly and disassembly of microtubule plus end-binding proteins [79]. Therefore, RhoGTPases play a significant role in several cellular processes, such as cell morphology, motility, mitosis, proliferation, adhesion, spreading, polarity, and migration [80].

B. jararacussu impaired retracting cell rear while making a large lamellipodium in the front (Fig. 5B2). This phenotype is commonly observed upon reduced Rho activity and/or increased relative Rac activity [80]. Cellular adhesion properties seemed to be more affected by B. neuwiedi venom (Fig. 5F2).

Actually, Jararhagin, a metalloproteinase isolated from the venom of B. jararaca [81], stimulates spreading, actin dynamics, and neurite outgrowth in neuroblastoma cells through the translocation of the Rac1 to the membrane fraction, suggesting its activation [82]. Russell's viper venom (RVV) induces morphological changes in human lung cancer cells A549 through modulation of Rac, Rho, and Cdc42 expression, which affects cellular-nuclear architecture related to cell proliferation, migration, and apoptosis [83]. Furthermore, a snake c-type lectin isolated from RVV, Daboialectin, alters the morphology of A549 cells via regulation of the cytoskeleton through RhoGTPases [69]. C. durissus terrificus venom and its main toxin, crotoxin, cause reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton in macrophages, and crotoxin significantly reduces membrane-associated RhoA and Rac1, negatively regulating the activity of RhoGTPases [84].

In addition to actin cytoskeleton modulation, RhoGTPases regulate cell cycle progression by acting in G1/S transition, progression of mitosis, and during cytokinesis [85].

It is tempting to suggest a potential involvement of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the observed cytoskeleton alterations. Snake venoms PLA2 and LAAOs can generate ROS (for review see Ref. [86]), which have been associated with reduction/oxidation modifications of cysteine and methionine residues of actin, actin-binding proteins, adhesion molecules, and signaling proteins involved in regulation dynamics [87].

Furthermore, the cytoskeletal disruption without cell cycle arrest induced by Bothrops spp. venoms could raise a question about how actin cytoskeleton dynamics relate to cell cycle progression control [85].

Along with growth factors and adhesion to extracellular matrix (ECM), the organization of the actin cytoskeleton has been implicated in cell cycle progression since disruption of the actin network by several drugs can lead to G1 arrest in a variety of cell lines [85,88].

In normal human fibroblasts, an organized cytoskeleton rather than cell adhesion per se is required to promote cell cycle progression through G1 [89]. Disruption of the actin network, inhibition of cell spreading, as well as signals provided by ECM, can block the cell cycle in the G1/S transition [89].

However, other studies demonstrated that inhibition of actin assembly can result in G1 arrest without interference in cell spreading, formation of focal adhesions, or normal cellular cleavage [90]. In addition, post-mitotic disruption of the actin cytoskeleton allows cell cycle progression independently of focal adhesion signaling, cytoskeletal organization, and cell shape, presumably because pre-existing cyclin D level is sufficient to drive cell cycle progression at the M-G1 border [91]. Cell cycle progression of cycling cells with disrupted cytoskeleton depends on MAPK activity, which allows cell proliferation independently of actin stress fibers, focal adhesions, or cell spreading [92]. Therefore, it is suggested that the integrity of the actin cytoskeleton and cell spreading is required for the cell cycle progression of quiescent cells (G0), but not for cells that are already in the cycle (M-G1 cells) [92]. Likewise, the lack of alteration in the cell cycle phases distribution in our results might suggest that the cells could be able to cycle and proliferate, even if cell spreading and actin organization were strongly perturbed.

In conclusion, our results indicated that Bothrops spp. venoms decreased cell viability of rat liver BRL-3A cells, without cell cycle arrest. No clear correlation was found between the IC50 and enzymatic or biological activities. Each venom induced remarkable but distinct morphological changes through microtubules and actin network disruption, reflecting the diversity of venom composition and related physiopathological effects.

This work contributed to understanding cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the Bothrops spp. venom cytotoxicity, which can help to improve envenomation treatment, as well as disclose potential therapeutic properties of snake venoms.

Funding

This work was supported by the “Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP- 2015/17177-6)”; “Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq-316504/2021-1)”; and “Fundação Butantan”. S.S.R. received fellowships from “Centro de Formação de Recursos Humanos do Sistema Único de Saúde da Secretaria de Estado da Saúde de São Paulo (CEFOR/SUS/SES/SP 586/2021)”. B.S.T. received a fellowship from “Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES-88887.508742/2020-00)”.

Author contribution statement

Bianca Sayuri Takayasu: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Sheila Silva Rodrigues: Performed the experiments.

Carlos Eduardo Madureira Trufen: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Glaucia Maria Machado-Santelli, Janice Onuki: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dra. Marisa Maria Teixeira da Rocha, who helped in the initial draft of the Material and Methods and promptly provided us with the stocked venoms and the respective control reports. We are also grateful to all the personnel of the Laboratory of Herpetology of Butantan Institute responsible for the maintenance of the indoor serpentarium and venom extraction, and the personnel of the Rodents Animal Facility at Butantan Institute for breeding and maintaining the prey used for feeding the snakes.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18317.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

figs1.

figs2.

figs3.

figs4.

References

- 1.Longbottom J., Shearer F.M., Devine M., Alcoba G., Chappuis F., Weiss D.J., Ray S.E., Ray N., Warrell D.A., Ruiz de Castañeda R., Williams D.J., Hay S.I., Pigott D.M. Vulnerability to snakebite envenoming: a global mapping of hotspots. Lancet. 2018;392:673–684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31224-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Team - Control of Neglected Diseases . WHO; 2019. Snakebite Envenoming: a Strategy for Prevention and Control. [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO - Departmental News, Snakebite . WHO; 2019. WHO Targets 50% Reduction in Deaths and Disabilities.https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/06-05-2019-snakebite-who-targets-50-reduction-in-deaths-and-disabilities [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matos R.R., Ignotti E. Incidence of venomous snakebite accidents by snake species in brazilian biomes. Ciência Saúde Coletiva. 2020;25:2837–2846. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232020257.31462018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mamede C.C.N., de Sousa Simamoto B.B., da Cunha Pereira D.F., de Oliveira Costa J., Ribeiro M.S.M., de Oliveira F. Edema, hyperalgesia and myonecrosis induced by Brazilian bothropic venoms: overview of the last decade. Toxicon. 2020;187:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2020.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almeida D.D., Viala V.L., Nachtigall P.G., Broe M., Lisle Gibbs H., De Toledo Serrano S.M., Moura-Da-Silva A.M., Ho P.L., Nishiyama M.Y., Junqueira-De-Azevedo I.L.M. Tracking the recruitment and evolution of snake toxins using the evolutionary context provided by the Bothrops jararaca genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021;118:1–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2015159118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Queiroz G.P., Pessoa L.A., V Portaro F.C., Furtado M. de Fátima D., V Tambourgi D. Interspecific variation in venom composition and toxicity of Brazilian snakes from Bothrops genus. Toxicon. 2008;52:842–851. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferreira M.L., Moura-da-Silva A.M., França F.O.S., Cardoso J.L., Mota I. Toxic activities of venoms from nine Bothrops species and their correlation with lethality and necrosis. Toxicon. 1992;30:1603–1608. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(92)90032-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alangode A., Rajan K., Nair B.G. Snake antivenom: challenges and alternate approaches. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020;181 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chong H.P., Tan K.Y., Tan C.H. Cytotoxicity of snake venoms and cytotoxins from two southeast asian cobras (Naja sumatrana, Naja kaouthia): exploration of anticancer potential, selectivity, and cell death mechanism. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.583587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panagopoulos A., Altmeyer M. The hammer and the dance of cell cycle control. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2021;46:301–314. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2020.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Visconti R., Della Monica R., Grieco D. Cell cycle checkpoint in cancer: a therapeutically targetable double-edged sword. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;35 doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0433-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiman K.G., Zhivotovsky B. Understanding cell cycle and cell death regulation provides novel weapons against human diseases. J. Intern. Med. 2017;281:483–495. doi: 10.1111/joim.12609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hohmann T., Dehghani F. The cytoskeleton-A complex interacting meshwork. Cells. 2019;8 doi: 10.3390/cells8040362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bates D., Eastman A. Microtubule destabilising agents: far more than just antimitotic anticancer drugs. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017;83:255–268. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janiszewska M., Primi M.C., Izard T. Cell adhesion in cancer: beyond the migration of single cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:2495–2505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV119.007759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin L.-M., Campillo C., Gourlay C., Huang J., Ren W., Zhao W., Cao L. Involvement of the actin machinery in programmed cell death. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.634849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kloc M., Uosef A., Wosik J., Kubiak J.Z., Ghobrial R.M. Virus interactions with the actin cytoskeleton—what we know and do not know about SARS-CoV-2. Arch. Virol. 2022;167:737–749. doi: 10.1007/s00705-022-05366-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acharya D., Reis R., Volcic M., Liu G.Q., Wang M.K., Chia B.S., Nchioua R., Groß R., Münch J., Kirchhoff F., Sparrer K.M.J., Gack M.U. Actin cytoskeleton remodeling primes RIG-I-like receptor activation. Cell. 2022;185:3588–3602.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO WHO guidelines for the production, control and regulation of snake antivenom immunoglobulins. Biol Aujourdhui. 2016;204:87–91. doi: 10.1051/jbio/2009043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gutiérrez J.M., Vargas M., Segura Á., Herrera M., Villalta M., Solano G., Sánchez A., Herrera C., León G. In vitro tests for assessing the neutralizing ability of snake antivenoms: toward the 3Rs principles. Front. Immunol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.617429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russell W.M.S., Burch R.L., Hume C.W. Univ Federation for Animal Welfare; 1959. Principle of Humane Experimental Techniques. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tannenbaum J., Bennett B.T. Russell and Burch's 3Rs then and now: the need for clarity in definition and purpose. J. Am. Assoc. Lab Anim. Sci. 2015;54:120–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cazarin K.C.C., Corrêa C.L., Zambrone F.A.D. Reduction, refinement and replacement of animal use in toxicity testing: an overview. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2004;40:289–299. doi: 10.1590/s1516-93322004000300004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tada H., Shiho O., ichi Kuroshima K., Koyama M., Tsukamoto K. An improved colorimetric assay for interleukin 2. J. Immunol. Methods. 1986;93:157–165. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(86)90183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritz C., Baty F., Streibig J.C., Gerhard D. Dose-response analysis using R. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wickham H. vol. 3. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Stat.; 2011. pp. 180–185. (ggplot2). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.R. Core Team, R: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2013. A language and environment for statistical computing.http://www.R-project.org [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takayasu B.S., Martins I.R., Garnique A.M.B., Miyamoto S., Machado-Santelli G.M., Uemi M., Onuki J. Biological effects of an oxyphytosterol generated by β-Sitosterol ozonization. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2020;696 doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2020.108654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghasemi M., Turnbull T., Sebastian S., Kempson I. The MTT assay: utility, limitations, pitfalls, and interpretation in bulk and single-cell analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms222312827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collares-Buzato C.B., de Paula Le Sueur L., da Cruz-Höfling M.A. Impairment of the cell-to-matrix adhesion and cytotoxicity induced by Bothrops moojeni snake venom in cultured renal tubular epithelia. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2002;181:124–132. doi: 10.1006/taap.2002.9404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Asmari A.K., Khan H.A., Manthiri R.A., Al-Khlaiwi A.A., Al-Asmari B.A., Ibrahim K.E. Protective effects of a natural herbal compound quercetin against snake venom-induced hepatic and renal toxicities in rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018;118:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopes-de-Souza L., Costal-Oliveira F., Stransky S., de Freitas C.F., Guerra-Duarte C., Braga V.M.M., Chávez-Olórtegui C. Development of a cell-based in vitro assay as a possible alternative for determining bothropic antivenom potency. Toxicon. 2019;170:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Souza L.L., Stransky S., Guerra-duarte C., Flor-sá A., Schneider F.S., Kalapothakis E., Chávez-olórtegui C. Determination of toxic activities in Bothrops spp. snake venoms using animal-free approaches: correlation between in vitro versus in vivo assays. Toxicol. Sci. 2015;147:458–465. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li C., Lan M., Lv J., Zhang Y., Gao X., Gao X., Dong L., Luo G., Zhang H., Sun J. Screening of the hepatotoxic components in Fructus gardeniae and their effects on rat liver BRL-3A cells. Molecules. 2019;24 doi: 10.3390/molecules24213920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hiu J.J., Yap M.K.K. Cytotoxicity of snake venom enzymatic toxins: phospholipase A2 and L-amino acid oxidase. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2020;48:719–731. doi: 10.1042/BST20200110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oliveira J.C.R., de Oca H.M., Duarte M.M., Diniz C.R., Fortes-Dias C.L. Toxicity of south american snake venoms measured by an in vitro cell culture assay. Toxicon. 2002;40:321–325. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(01)00229-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okumu M.O., Mbaria J.M., Gikunju J.K., Mbuthia P.G., Madadi V.O., Ochola F.O., Jepkorir M.S. Artemia salina as an animal model for the preliminary evaluation of snake venom-induced toxicity. Toxicon X. 2021;12 doi: 10.1016/j.toxcx.2021.100082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verity E.E., Stewart K., Vandenberg K., Ong C., Rockman S. Potency testing of venoms and antivenoms in embryonated eggs: an ethical alternative to animal testing. Toxins. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/toxins13040233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Serrano S.M.T., Zelanis A., Kitano E.S., Tashima A.K. Analysis of the snake venom peptidome. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018;1719:349–358. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7537-2_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calvete J.J. Antivenomics and venom phenotyping: a marriage of convenience to address the performance and range of clinical use of antivenoms. Toxicon. 2010;56:1284–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiménez N., Escalante T., Gutiérrez J.M., Rucavado A. Skin pathology induced by snake venom metalloproteinase: acute damage, revascularization, and re-epithelization in a mouse ear model. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2008;128:2421–2428. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Serrano S.M.T., Maroun R.C. Snake venom serine proteinases: sequence homology vs. substrate specificity, a paradox to be solved. Toxicon. 2005;45:1115–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galvão I., Sugimoto M.A., Vago J.P., Machado M.G., Sousa L.P. In: Immunopharmacology and Inflammation. Riccardi C., Levi-Schaffer F., Tiligada E., editors. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2018. Mediators of inflammation; pp. 3–32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Izidoro L.F.M., Sobrinho J.C., Mendes M.M., Costa T.R., Grabner A.N., Rodrigues V.M., Da Silva S.L., Zanchi F.B., Zuliani J.P., Fernandes C.F.C., Calderon L.A., Stábeli R.G., Soares A.M. Snake venom L-amino acid oxidases: trends in pharmacology and biochemistry. BioMed Res. Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/196754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ogawa T., Chijiwa T., Oda-Ueda N., Ohno M. Molecular diversity and accelerated evolution of C-type lectin-like proteins from snake venom. Toxicon. 2005;45:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gutiérrez J.M., Rucavado A., Escalante T., Herrera C., Fernández J., Lomonte B., Fox J.W. Unresolved issues in the understanding of the pathogenesis of local tissue damage induced by snake venoms. Toxicon. 2018;148:123–131. doi: 10.1016/J.TOXICON.2018.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mamede C.C.N., De Sousa B.B., Pereira D.F.D.C., Matias M.S., De Queiroz M.R., De Morais N.C.G., Vieira S.A.P.B., Stanziola L., De Oliveira F. Comparative analysis of local effects caused by Bothrops alternatus and Bothrops moojeni snake venoms: enzymatic contributions and inflammatory modulations. Toxicon. 2016;117:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zychar B.C., Dale C.S., Demarchi D.S., Gonçalves L.R.C. Contribution of metalloproteases, serine proteases and phospholipases A2 to the inflammatory reaction induced by Bothrops jararaca crude venom in mice. Toxicon. 2010;55:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zambelli V.O., Picolo G., Fernandes C.A.H., Fontes M.R.M., Cury Y. Secreted phospholipases A 2 from animal venoms in pain and analgesia. Toxins. 2017;9:1–27. doi: 10.3390/toxins9120406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Costal-Oliveira F., Stransky S., Guerra-Duarte C., De Souza D.L.N., Vivas-Ruiz D.E., Yarlequé A., Sanchez E.F., Chávez-Olórtegui C., Braga V.M.M. L-amino acid oxidase from Bothrops atrox snake venom triggers autophagy, apoptosis and necrosis in normal human keratinocytes. Sci. Rep. 2019;9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37435-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Galluzzi L., Vitale I., Aaronson S.A., Abrams J.M., Adam D., Agostinis P., Alnemri E.S., Altucci L., Amelio I., Andrews D.W., Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli M., V Antonov A., Arama E., Baehrecke E.H., Barlev N.A., Bazan N.G., Bernassola F., Bertrand M.J.M., Bianchi K., V Blagosklonny M., Blomgren K., Borner C., Boya P., Brenner C., Campanella M., Candi E., Carmona-Gutierrez D., Cecconi F., Chan F.K.M., Chandel N.S., Cheng E.H., Chipuk J.E., Cidlowski J.A., Ciechanover A., Cohen G.M., Conrad M., Cubillos-Ruiz J.R., Czabotar P.E., D'Angiolella V., Dawson T.M., Dawson V.L., De Laurenzi V., De Maria R., Debatin K.M., Deberardinis R.J., Deshmukh M., Di Daniele N., Di Virgilio F., Dixit V.M., Dixon S.J., Duckett C.S., Dynlacht B.D., El-Deiry W.S., Elrod J.W., Fimia G.M., Fulda S., García-Sáez A.J., Garg A.D., Garrido C., Gavathiotis E., Golstein P., Gottlieb E., Green D.R., Greene L.A., Gronemeyer H., Gross A., Hajnoczky G., Hardwick J.M., Harris I.S., Hengartner M.O., Hetz C., Ichijo H., Jäättelä M., Joseph B., Jost P.J., Juin P.P., Kaiser W.J., Karin M., Kaufmann T., Kepp O., Kimchi A., Kitsis R.N., Klionsky D.J., Knight R.A., Kumar S., Lee S.W., Lemasters J.J., Levine B., Linkermann A., Lipton S.A., Lockshin R.A., López-Otín C., Lowe S.W., Luedde T., Lugli E., MacFarlane M., Madeo F., Malewicz M., Malorni W., Manic G., Marine J.C., Martin S.J., Martinou J.C., Medema J.P., Mehlen P., Meier P., Melino S., Miao E.A., Molkentin J.D., Moll U.M., Muñoz-Pinedo C., Nagata S., Nuñez G., Oberst A., Oren M., Overholtzer M., Pagano M., Panaretakis T., Pasparakis M., Penninger J.M., Pereira D.M., Pervaiz S., Peter M.E., Piacentini M., Pinton P., Prehn J.H.M., Puthalakath H., Rabinovich G.A., Rehm M., Rizzuto R., Rodrigues C.M.P., Rubinsztein D.C., Rudel T., Ryan K.M., Sayan E., Scorrano L., Shao F., Shi Y., Silke J., Simon H.U., Sistigu A., Stockwell B.R., Strasser A., Szabadkai G., Tait S.W.G., Tang D., Tavernarakis N., Thorburn A., Tsujimoto Y., Turk B., Vanden Berghe T., Vandenabeele P., Vander Heiden M.G., Villunger A., Virgin H.W., Vousden K.H., Vucic D., Wagner E.F., Walczak H., Wallach D., Wang Y., Wells J.A., Wood W., Yuan J., Zakeri Z., Zhivotovsky B., Zitvogel L., Melino G., Kroemer G. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the nomenclature committee on cell death 2018. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:486–541. doi: 10.1038/s41418-017-0012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bernardes-Oliveira E., Gomes D.L., Palomino G.M., Farias K.J.S., Da Silva W.D., Rocha H.A.O., Gonçalves A.K., Fernandes-Pedrosa M.D.F., Crispim J.C.D.O. Bothrops jararaca and Bothrops erythromelas snake venoms promote cell cycle arrest and induce apoptosis via the mitochondrial depolarization of cervical cancer cells. Evid. Bas. Comp. Alter. Med. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/1574971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nolte S., de Castro Damasio D., Baréa A.C., Gomes J., Magalhães A., Zischler L.F.C.M., Stuelp-Campelo P.M., Elífio-Esposito S.L., Roque-Barreira M.C., Reis C.A., Moreno-Amaral A.N. BJcuL, a lectin purified from Bothrops jararacussu venom, induces apoptosis in human gastric carcinoma cells accompanied by inhibition of cell adhesion and actin cytoskeleton disassembly. Toxicon. 2012;59:81–85. doi: 10.1016/J.TOXICON.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Vasconcelos Azevedo F.V.P., Zóia M.A.P., Lopes D.S., Gimenes S.N., Vecchi L., Alves P.T., Rodrigues R.S., Silva A.C.A., Yoneyama K.A.G., Goulart L.R., de Melo Rodrigues V. Antitumor and antimetastatic effects of PLA2-BthTX-II from Bothrops jararacussu venom on human breast cancer cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;135:261–273. doi: 10.1016/J.IJBIOMAC.2019.05.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.da Silva C.P., Costa T.R., Paiva R.M.A., Cintra A.C.O., Menaldo D.L., Antunes L.M.G., V Sampaio S. Antitumor potential of the myotoxin BthTX-I from Bothrops jararacussu snake venom: evaluation of cell cycle alterations and death mechanisms induced in tumor cell lines. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2015;21:44. doi: 10.1186/s40409-015-0044-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bezerra P.H.A., Ferreira I.M., Franceschi B.T., Bianchini F., Ambrósio L., Cintra A.C.O., Sampaio S.V., De Castro F.A., Torqueti M.R. BthTX-I from Bothrops jararacussu induces apoptosis in human breast cancer cell lines and decreases cancer stem cell subpopulation. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2019;25 doi: 10.1590/1678-9199-jvatitd-2019-0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zamunér S.R., Da Cruz-Höfling M.A., Corrado A.P., Hyslop S., Rodrigues-Simioni L. Comparison of the neurotoxic and myotoxic effects of Brazilian Bothrops venoms and their neutralization by commercial antivenom. Toxicon. 2004;44:259–271. doi: 10.1016/J.TOXICON.2004.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moes M., Boonstra J., Regan-Klapisz E. Novel role of cPLA 2 a in membrane and actin dynamics. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010;67:1547–1557. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0267-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Glenn H.L., Jacobson B.S. Arachidonic Acid signaling to the cytoskeleton: the role of cyclooxygenase and cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in actin bundling. Cytoskeleton. 2002;53:239–250. doi: 10.1002/cm.10072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ghosh P.K., Vasanji A., Murugesan G., Eppell S.J., Graham L.M., Fox P.L. Membrane microviscosity regulates endothelial cell motility. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;28:October. doi: 10.1038/ncb873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oliveira A.L., Viegas M.F., Da Silva S.L., Soares A.M., Ramos M.J., Fernandes P.A. The chemistry of snake venom and its medicinal potential. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2022;6:451–469. doi: 10.1038/s41570-022-00393-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fernández J., Caccin P., Koster G., Lomonte B., Gutiérrez J.M., Montecucco C., Postle A.D. Muscle phospholipid hydrolysis by Bothrops asper Asp49 and Lys49 phospholipase A2 myotoxins - distinct mechanisms of action. FEBS J. 2013;280:3878–3886. doi: 10.1111/febs.12386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xiao H., Pan H., Liao K., Yang M., Huang C. Snake venom PLA2, a promising target for broad-spectrum antivenom drug development. BioMed Res. Int. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/6592820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Burke J.E., Dennis E.A. Phospholipase A2 biochemistry. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2009;23:49–59. doi: 10.1007/s10557-008-6132-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schaloske R.H., Dennis E.A. The phospholipase A2 superfamily and its group numbering system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2006;1761:1246–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Castro-Amorim J., de Oliveira A.N., Da Silva S.L., Soares A.M., Mukherjee A.K., Ramos M.J., Fernandes P.A. Catalytically active snake venom PLA2 enzymes: an overview of its elusive mechanisms of reaction. J. Med. Chem. 2023;66:5364–5376. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.De Carvalho D.D., Schmitmeier S., Novello J.Â.C., Markland F.S. Effect of BJcuL (a lectin from the venom of the snake Bothrops jararacussu) on adhesion and growth of tumor and endothelial cells. Toxicon. 2001;39:1471–1476. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(01)00106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pathan J., Mondal S., Sarkar A., Chakrabarty D. Daboialectin, a C-type lectin from Russell's viper venom induces cytoskeletal damage and apoptosis in human lung cancer cells in vitro. Toxicon. 2017;127:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.D’amélio F., Vigerelli H., Rossan Á., Prieto-Da-Silva B., Frare E.O., Batista I.D.F.C., Pimenta D.C., Kerkis I. Bothrops moojeni venom and its components strongly affect osteoclasts' maturation and protein patterns. Toxins. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/toxins13070459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Donne R., Sangouard F., Celton-Morizur S., Desdouets C. Hepatocyte polyploidy: driver or gatekeeper of chronic liver diseases. Cancers. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/cancers13205151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Matsumoto T. Implications of polyploidy and ploidy alterations in hepatocytes in liver injuries and cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23 doi: 10.3390/ijms23169409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Miyaoka Y., Ebato K., Kato H., Arakawa S., Shimizu S., Miyajima A. Hypertrophy and unconventional cell division of hepatocytes underlie liver regeneration. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:1166–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schmidt A., Hall A. Guanine nucleotide exchange factors for Rho GTPases: turning on the switch. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1587–1609. doi: 10.1101/gad.1003302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bernards A. GAPs galore! A survey of putative Ras superfamily GTPase activating proteins in man and Drosophila. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Canc. 2003;1603:47–82. doi: 10.1016/S0304-419X(02)00082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dransart E., Olofsson B., Cherfils J. RhoGDIs revisited: novel roles in Rho regulation. Traffic. 2005;6:957–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Spiering D., Hodgson L. Dynamics of the rho-family small GTPases in actin regulation and motility. Cell Adhes. Migrat. 2011;5:170–180. doi: 10.4161/cam.5.2.14403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gautreau A.M., Fregoso F.E., Simanov G., Dominguez R. Nucleation, stabilization, and disassembly of branched actin networks. Trends Cell Biol. 2022;32:421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2021.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van Haren J., Wittmann T. Microtubule plus end dynamics − Do we know how microtubules grow?: cells boost microtubule growth by promoting distinct structural transitions at growing microtubule ends. Bioessays. 2019;41 doi: 10.1002/bies.201800194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ridley A.J. Rho GTPase signalling in cell migration. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015;36:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Paine M.J.I., Desmond H.P., David R., Theakston G., Crampton J.M. Purification, cloning, and molecular characterization of a high molecular weight hemorrhagic metalloprotease, Jararhagin, from Bothrops jararaca venom - insights into the disintegrin gene family. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:22869–22876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Costa E.P., Del Debbio C.B., Cintra L.C., da Fontoura Costa L., Hamassaki D.E., Santos M.F. Jararhagin, a snake venom metalloprotease-disintegrin, activates the Rac1 GTPase and stimulates neurite outgrowth in neuroblastoma cells. Toxicon. 2008;52:380–384. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.04.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pathan J., Martin A., Chowdhury R., Chakrabarty D., Sarkar A. Russell's viper venom affects regulation of small GTPases and causes nuclear damage. Toxicon. 2015;108:216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sampaio S.C., Santos M.F., Costa E.P., Rangel-Santos A.C., Carneiro S.M., Curi R., Cury Y. Crotoxin induces actin reorganization and inhibits tyrosine phosphorylation and activity of small GTPases in rat macrophages. Toxicon. 2006;47:909–919. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Heng Y.W., Koh C.G. Actin cytoskeleton dynamics and the cell division cycle. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010;42:1622–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Urra F.A., Araya-Maturana R. Putting the brakes on tumorigenesis with snake venom toxins: new molecular insights for cancer drug discovery. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022;80:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schnoor M., Ugalde C., Samstag Y., Balta E., Kramer J. Redox regulation of the actin cytoskeleton in cell migration and adhesion: on the way to a spatiotemporal view. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;1 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.618261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Assoian R.K., Schwartz M.A. Integrins and RTKs in the regulation of G 1 phase cell-cycle progression. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2001;11:48–53. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bohmer R.-M., Scharf E., Assoian R.K. Cytoskeletal integrity Is required throughout the mitogen stimulation phase of the cell cycle and mediates the anchorage-dependent expression of cyclin D1. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1996;7:101–111. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Huang S., Chen C.S., Ingber D.E. Control of cyclin D1, p27 Kip1 , and cell cycle progression in human capillary endothelial cells by cell shape and cytoskeletal tension. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1998;9:3179–3193. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.11.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Margadant C., van Opstal A., Boonstra J. Focal adhesion signaling and actin stress fibers are dispensable for progression through the ongoing cell cycle. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:66–76. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Margadant C., Cremers L., Sonnenberg A., Boonstra J. MAPK uncouples cell cycle progression from cell spreading and cytoskeletal organization in cycling cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013;70:293–307. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1130-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]