Abstract

Invasive fungal infections are on the rise, leading to a continuous demand for antifungal antibiotics. Rare actinomycetes have been shown to contain a variety of interesting compounds worth exploring. In this study, 15 strains of rare actinobacterium Gordonia were isolated from the gut of Periplaneta americana and screened for their anti-fungal activity against four human pathogenic fungi. Strain WA8-44 was found to exhibit significant anti-fungal activity and was selected for bioactive compound production, separation, purification, and characterization. Three anti-fungal compounds, Collismycin A, Actinomycin D, and Actinomycin X2, were isolated from the fermentation broth of Gordonia strain WA8-44. Of these, Collismycin A was isolated and purified from the secondary metabolites of Gordonia for the first time, and its anti-filamentous fungi activity was firstly identified in this study. Molecular docking was carried out to determine their hypothetical binding affinities against nine target proteins of Candida albicans. Chitin Synthase 2 was found to be the most preferred antimicrobial protein target for Collismycin A, while 1,3-Beta-Glucanase was the most preferred anti-fungal protein target for Actinomycin D and Actinomycin X2. ADMET prediction revealed that Collismycin A has favorable oral bioavailability and little toxicity, making it a potential candidate for development as an orally active medication.

Keywords: Antifungal, Periplaneta americana, Gordonia, Molecular docking, Collismycin A

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The incidence of invasive fungal infections is on the rise due to an increase in the number of immunocompromised patients [1] and the emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains, particularly those resistant to azole drugs [2]. There is an urgent need to develop new anti-fungal antibiotics with novel mechanisms of action to efficiently combat these infections [3]. To address this challenge, researchers have undertaken a diverse range of approaches, including the discovery of new bioactive molecules and the advancement of novel techniques [4]. Microorganisms are an inexhaustible source of new bioactive molecules [5], with actinomycetes having produced nearly 10,000 antibiotics to date [6]. However, finding new compounds from traditional sources has become less likely in recent years [7], leading scientists to explore alternative microbial sources such as rare actinomycetes, insect-associated actinomycetes, and underrepresented taxa [8].

The genus Gordonia is a kind of rare actinomycetes [9]. Currently, most studies surrounding Gordonia bacteria focus on biodegradation [10,11]. There are few reports on their secondary metabolites, particularly those with antimicrobial properties. The first secondary metabolites to be identified from Gordonia were three novel steroid molecules called bendigoles A, B, and C [12]. Ana Patricia Gra et al. isolated the first three strains of Gordonia identified with antibacterial activity from Erylus discophorus sponges [13], and Park et al. found that Gordonia SP. KMC005 co-cultured with Streptomyces tendae KMC006 could produce a new antibacterial substance, gordonic acid [14]. However, no potential bioactive chemicals from Gordonia with anti-fungal action have been reported.

P. americana is a human health pest on a global scale and has been used in Chinese traditional medicine (TCM) for several thousand years [15]. P. americana extracts have been shown to improve immunity, blood circulation, and wound healing effects. Living in polluted areas has also made P. americana more resilient to microbial diseases [16], and bacteria in the P. americana gut are likely to produce antimicrobial compounds that aid the insect immune system.

In our previous studies, we found that P. americana gut-dwelling bacteria generate anti-bacterial chemicals that may be a source of new anti-bacterial compounds [[17], [18], [19], [20]]. The current investigation aimed to determine if secondary metabolites generated by Gordonia, isolated from the gut of P. americana, have any anti-fungal effects. The metabolites produced by Gordonia strain WA8-44 were purified, characterized, and assessed for their anti-fungal activities. Additionally, we used in silico models to assess their ADMET profiles and predict how they bind to known molecular targets in C. albicans.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sampling, pre-treatment, and isolation of actinobacteria

The P. americanas used in this study were collected from the campus of Guangdong Pharmaceutical University. Actinobacteria were isolated from the gut of P. americana using Lima et al.'s method [21]. Briefly, the P. americana samples were washed with sterile water, 75% ethanol, and 0.47 mol/L sodium hypochlorite. The gut was then ground and diluted to the required concentration (10, 5, 2.5 μg/mL). The samples were spread onto culture plates containing 0.25 mmol/L potassium dichromate and incubated at 28 °C for seven days. The visible colonies were isolated and purified based on their morphological characteristics.

2.2. Test pathogens for the current study

There were four fungi for testing; the fungi were Candida albicans ATCC 10231, Trichophyton rubrum ATCC 60836, Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC 96918, and Aspergillus niger ATCC 16404. All strains were obtained from Guangdong Microbial Culture Collection Center.

2.3. Screening of gordonia for anti-fungal activity

We evaluated the anti-fungal activity of Gordonia strains against C. albicans using the Oxford cup method. Briefly, C. albicans suspension (4 × 106 CFU/mL) was swabbed onto PDA plates, and 200 μL of fermentation broth was added into an Oxford cup, followed by incubation for 24 h at 28 °C. We used amphotericin B (34.62 μmol/L) as a positive control and recorded the diameters of inhibition zones. For assessing the anti-fungal activity against T. rubrum, A. fumigatus, and A. niger, we performed plate confrontation assays [22]. Here, the Gordonia strain was inoculated on one side of PDA plates and incubated for four days at 28 °C. Subsequently, spores of T. rubrum ATCC 60836, A. fumigatus ATCC 96918, and A. niger ATCC 16404 were spotted on the other side of the plate, followed by incubation at 28 °C for 3–5 days. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

2.4. Molecular identification and phylogenetic analysis of isolates

The micromorphological characteristics of the strains were observed using a scanning electron microscope (Quanta FEG 200, USA). Genomic DNA was extracted from WA8-44 using the GenElute Bacterial Genomic DNA Kit (Sigma). The 16 S rRNA gene was amplified using primers 27 F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492 R (5′-TACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) from the 15 isolates, and the resulting PCR products were sequenced by Invitrogen Co. The obtained sequences were submitted to NCBI, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with MEGA 5.0 software.

2.5. Bioassay-guided isolation and purification of anti-fungal compounds

An inoculum of the WA8-44 strain was cultured it in ISP-1 broth for three days at 28 °C 15 mL of the seed culture was then transferred to a 500 mL conical flask containing 300 mL ISP-2 medium and agitated on a rotary shaker at 28 °C for seven days. The fermentation broth was concentrated by centrifugation at 1708×g for 25 min, and the supernatant was extracted three times using ethyl acetate. The clear supernatant was then evaporated using a rotary flash evaporator and freeze-dried, yielding 12.0 g crude extract.

The crude extract was fixed on silica gel (300–400 mesh, 680 g) and fractionated through flash chromatography as ten fractions. Fractions 2 and 3 exhibited strong anti-fungal activity and were selected for further purification. Fraction 2 was fractionated using open-column chromatography with silica gel and yielded four subfractions (fractions 2–1 to 2–4). Fraction 2–3 was further purified using preparative RP-HPLC with a YMC-Pack ODS-A/S-5 μm/12 nm 250 × 10.0 mm column, a flow rate of 3 mL/min, MeOH/H2O (80% at 20 and 22 min), with UV detection at 210 nm. This led to the isolation of two compounds, A (182 mg) and B (20 mg). Fraction 3 was subjected to open-column chromatography using silica gel (gradient of PE/EA) and Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography with MeOH as the eluent. Compound C (29 mg) was then purified using preparative RP-HPLC with a YMC-Pack ODS-A/S-5 μm/12 nm 250 × 10.0 mm column, a flow rate of 3 mL/min, and MeOH/H2O (70% in 25 min), with UV detection at 210 nm.

2.6. Minimum inhibitory concentration testing

Following the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines, the M27-A3 method was used to determine the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of C. albicans [23], while the M38-A2 method was used for filamentous fungi [24]. To prepare the samples, C. albicans was diluted with RPMI1640 to a final concentration of 0.5–2.5 × 103 spores/ml, A. fumigatus, and A. niger were diluted to 1 × 104 spores/ml, and T. rubrum was diluted to 2 × 103 spores/ml. The test samples were dissolved in DMSO and then diluted with RPMI1640 to a series of concentrations. Next, 100 μL of the test sample solutions were added to 100 μL of the cell suspension and incubated for 48 h. Each experiment was repeated three times.

2.7. Structural prediction of antifungal compounds

The NMR spectra of the chemicals were measured using a 600 MHz spectrometer (Brucker AVANCE III, 600 M, Germany), with tetramethyl silane (TMS) as the internal reference and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as the solvent. The compounds were injected separately into a Triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific TSQ Endura™, USA) to obtain mass spectra. All solvents used for extraction were of LR grade, whereas HPLC-grade solvents were used for analysis.

Compound A, orange-red crystalline powder, 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.60 (d, 1H); 7.35 (d, 1H); 5.20 (qd, 1H); 5.20 (qd, 1H); 4.60 (d, 1H); 4.51 (dd, 1H); 3.65 (d, 2H); 3.62 (d, 2H); 2.92 (s, 3H); 2.90 (s, 3H); 2.90 (s, 3H); 2.90 (s, 3H); 2.86 (s, 3H); 2.86 (s, 3H); 2.68 (s, 3H); 2.52 (s, 3H); 1.23 (d, 3H); 1.23 (d, 3H); 1.11 (d, 3H); 1.11 (d, 3H); 0.91 (d, 3H); 0.87 (d, 6H); 0.87 (d, 6H); 0.94 (d, 3H); 0.73 (d, 6H); 0.73 (d, 6H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 179.10, 173.69, 173.39, 173.34, 173.32, 169.09, 168.63, 167.79, 167.70, 166.71, 166.63, 166.57, 166.42, 147.69, 145.93, 145.16, 140.56, 132.55, 130.43, 129.15, 127.85, 125.80, 113.62, 101.67, 75.13, 75.04, 71.42, 71.22, 58.93, 58.79, 56.62, 56.38, 55.23, 54.88, 51.46, 51.44, 47.67, 47.43, 39.36, 39.24, 35.03, 34.97, 31.85, 31.61, 31.33, 31.05, 29.36, 27.06, 26.99, 23.08, 22.90, 21.73, 21.64, 19.36, 19.32, 19.18, 19.15, 19.11, 19.07, 17.81, 17.38, 15.14, 7.84; HR-ESI-MS m/z 1277.43 [M+Na]+, HR-ESI-MS m/z 1255.49 [M+H]+.

Compound B, orange-red crystalline powder, 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.24 (d, 1H); 7.71 (d, 1H); 7.66 (d, 1H); 7.14 (d, 1H); 6.55 (d, 1H); 5.93 (d, 1H); 5.25 (qb, 1H); 5.16 (qd, 1H); 4.72 (d, 1H); 4.57 (dd, 1H); 4.57 (d, 1H); 4.57 (d, 1H); 4.50 (dd, 1H); 3.98 (d, 1H); 3.87 (m, 1H); 3.83 (dd, 1H); 3.72 (m, 1H); 3.71 (dd, 1H); 3.64 (d, 1H); 3.64 (d, 1H); 3.58 (dd, 1H); 3.00 (s, 3H); 2.93 (s, 3H); 2.88 (s, 3H); 2.88 (s, 3H); 2.67 (m, 1H); 2.67 (m, 1H); 2.67 (m, 1H); 2.67 (m, 1H); 2.67 (m, 1H); 2.33 (d, 1H); 2.22 (m, 1H); 2.10 (m, 1H); 2.08 (m, 1H); 2.03 (m, 1H); 1.85 (dd, 1H); 1.26 (d, 3H); 1.14 (d, 3H); 1.12 (d, 3H); 1.12 (d, 3H); 0.95 (d, 3H); 0.95 (d, 3H); 0.90 (d, 3H); 0.85 (d, 3H); 0.74 (d, 3H); 0.74 (d, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 208.97, 179.17, 174.16, 173.67, 173.26, 172.83, 169.11, 168.87, 167.66, 167.63, 166.74, 166.46, 166.28, 166.07, 147.50, 146.09, 145.18, 140.67, 132.23, 130.51, 129.30, 128.07, 126.28, 113.79, 101.87, 74.90, 74.79, 71.58, 71.38, 58.69, 57.31, 56.60, 55.09, 54.89, 54.44, 53.01, 51.49, 51.45, 47.59, 42.05, 39.53, 39.35, 35.08, 34.93, 32.01, 31.85, 31.17, 27.17, 27.10, 23.12, 21.86, 21.75, 19.39, 19.36, 19.23, 19.20, 19.07, 18.97, 17.83, 17.29, 15.22, 7.93. HR-ESI-MS m/z 1291.17 [M+Na]+, HR-ESI-MS m/z 1269.41 [M+H]+.

Compound C, opalescent powder, 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.63 (s, 1H), 9.09 (s, 1H), 8.66 (m, 1H), 8.52 (d, 1H), 8.03 (s, 1H), 7.85 (td, 1H), 7.34 (dd, 1H), 4.12 (s, 3H), 2.38 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.37, 157.46, 155.15, 152.56, 148.93, 148.05, 137.18, 124.34, 122.17, 121.87, 103.71, 56.43, 18.52; HR-ESI-MS m/z 275.97 [M+H]+.

2.8. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis

The morphological changes induced in C. albicans by the active compounds were observed using SEM, as described by Jeyanthi et al. [25]. 4 × MIC of the active compounds were applied to C. albicans suspensions (1–5 × 105 CFU/mL) for 48 h at 28 °C. The cells were then fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C overnight, washed three times with PBS for 20 min, and subsequently underwent a series of ethanol washes (30–100%). Finally, SEM images were obtained using a Quanta FEG 200 FESEM, which was operated at an accelerating voltage of 2–19 KV under standard operating conditions.

2.9. In-silico molecular docking studies

Nine molecular targets associated with antimicrobial biological activity in C. albicans were selected for the study. The crystal structures of dihydrofolate reductase (PDB ID: 1M78), secreted aspartic proteinase 5 (PDB ID: 2QZX) [26], 3-beta-glucanase (PDB ID: 4M80), lanosterol 14-alpha demethylase (PDB ID: 5V5Z) [27], chitin synthase 2 (PDB ID: 6LNK), fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase (PDB ID: 7V6F) [28], and N-myristoyltransferase (PDB ID: 1IYL) [29], were obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/). Squalene epoxidase (AF ID: Q92206) [30] and thymidylate synthase (AF ID: P12461) were obtained from the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/). The 3D structures of the ligands, including Collismycin A (PubChem CID: 135482271), Actinomycin D (PubChem CID: 2019), and Actinomycin X2 (PubChem CID: 159855), were downloaded from the PubChem Database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The 3D structures of the ligands were constructed and minimized using Chimera 1.16. The molecular docking was carried out using iGEMDOCK v2.1 with default parameter values [31], and protein-ligand interactions were analyzed using Biovia Discovery Studio Visualizer v2021.

2.10. In-silico drug-likeness and ADMET prediction of bioactive compounds

We utilized several web tools, including PreADMET (https://preadmet.qsarhub.com/) [32], pkCSM (https://biosig.lab.uq.edu.au/pkcsm) [33], ProTox-II (https://tox-new.charite.de/protox_II/) [34], and SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/) [35], to predict drug-likeness and ADMET properties of the bioactive compounds.

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and screening

15 strains of Gordonia were isolated from the gut of P. americana (as shown in Fig. 1AB). Among these strains, 8 strains demonstrated anti-C. albicans activity, 4 strains showed anti-T. rubrum activity, 3 strains displayed anti-A. fumigatus activity, and 3 strains exhibited anti-A. niger activity (as listed in Table 1). Notably, strain WA8-44 demonstrated significant activity against all the tested fungi. Therefore, strain WA8-44 was chosen for further investigation (as shown in Fig. 3ABCD and Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Morphological characteristics of strain Gordonia. A Results of identification of colonies of strain Gordonia on Gauze's medium. B Observation of culture plates by optical microscopy following Gram staining ( × 100).

Table 1.

Antimicrobial activity of Gordonia fermented liquid (mm growth inhibition, n = 3).

| Strains | C. albicans | T. rubrum | A. fumigatus | A. niger |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WA1-1 | – | – | – | – |

| WA2-5 | 32.5 ± 3.6 | + | – | – |

| WA2-19 | 18.7 ± 2.5 | – | – | – |

| WA3-1-78 | 12.1 ± 1.9 | – | – | – |

| WA4-31 | 30.8 ± 3.7 | + | + | + |

| WA4-43 | – | – | – | – |

| WA8-44 | 25.8 ± 3.2 | + | + | + |

| WA12-1-1 | 16.6 ± 2.7 | + | + | + |

| WA14-2-8 | 14.1 ± 1.5 | – | – | – |

| WA20-4-4 | – | – | – | – |

| WA23-2-5 | 12.2 ± 1.1 | – | – | – |

| WA23-2-6 | – | – | – | – |

| WA23-4-1 | – | – | – | – |

| WA23-4-2 | – | – | – | – |

| WA23-4-10 | – | – | – | – |

| Amphotericin B | 22.4 ± 2.8 | + | + | + |

Note: + Strain growth inhibited, - Strain growth is not inhibited.

Fig. 3.

Anti-fungal activity of Gordonia sp. WA8-44. (A1) A. niger, (A2) Confrontation assay between A. niger and Gordonia sp. WA8-44; (B1) A. fumigatus, (B2) Confrontation assay between A. fumigatus and Gordonia sp. WA8-44; (C1) R. rubrum, (C2) Confrontation assay between R. rubrum and Gordonia sp. WA8-44; (D) Antifungal activity of Gordonia sp. WA8-44 against C. albicans using the Oxford cup method.

3.2. Identification of potent isolate WA8-44

Gordonia sp. WA8-44 exhibited good growth on Gauze's Agar No. 1 medium, with irregularly shaped and raised colonies that were either reddish-brown or milky yellow, with a moist and opaque surface (Fig. 2A). The strain was observed to be a gram-positive bacterium based on Gram staining results (Fig. 2B). Short, smooth, rod-shaped cell was observed using SEM (Fig. 2CD).

Fig. 2.

Morphological characteristics of Gordonia sp. WA8-44. A Colony morphology of Gordonia sp. WA8-44 on Gauze's No. 1 medium. B Gram stain of Gordonia sp. WA8-44. C&D Scanning electron micrograph of Gordonia sp. WA8-44. E Neighbor-Joining phylogenetic tree based on 16 S rRNA gene sequence showing the relationship between strain Gordonia sp. WA8-44 and representatives of some other related taxa.

The 16 S rRNA sequence of strain WA8-44 was submitted to NCBI, and an accession number was obtained in GeneBank (MH605445). A phylogenetic tree of strain WA8-44, based on the Neighbor-Joining method, formed a single clade involving Gordonia terrae (NR_118,598) with a similarity of 99.55% (Fig. 2E). Molecular characterization confirmed that the strain belonged to Gordonia terrae.

3.3. Extraction, purification, and characterization

A bioassay-guided investigation was performed to isolate the active constituents from an ethyl acetate extract of strain WA8-44. Gradient elution was performed using different organic solvents and the activity of different fractions was determined using C. albicans ATCC 10231 as an indicator. The active components were further purified and the final purification of the sub-fractions was achieved by preparative RP-HPLC. In total, three active compounds were isolated and identified (Fig. 1S–9S). Compound A appeared as an orange-red crystalline powder and had a HR-ESI-MS m/z value of 1277.43 [M+Na]+ and 1255.49 [M+H]+. Compound B was also an orange-red crystalline powder and had a HR-ESI-MS m/z value of 1291.17 [M+Na]+ and 1269.41 [M+H]+. Compound C was an opalescent powder and had a HR-ESI-MS m/z value of 275.97 [M+H]+. The chemical structures of the purified compounds were elucidated based on HR-ESI-MS, 1H NMR, and 13C NMR. Consequently, Compounds A-C were identified as Actinomycin D, Actinomycin X2, and Collismycin A, respectively.

3.4. Anti-fungal activity of isolated bioactive compounds

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of the isolated compounds are presented in Table 2. Actinomycin D, Actinomycin X2, and Collismycin A showed potent activity against C. albicans ATCC 10231, T. rubrum ATCC 60836, A. fumigatus ATCC 96918, and A. niger ATCC 16404, with MICs ranging from 3.19–101.96 μmol/L. This suggests that Actinomycin D, Actinomycin X2, and Collismycin A have the potential to be potent antifungal agents with broad spectra. The anti-C. albicans effect of Actinomycin D (Fig. 4CG), Actinomycin X2 (Fig. 4BF), and Collismycin A (Fig. 4DH) was observed through SEM analysis. The cell membrane structure of C. albicans ATCC 10231 was damaged after treatment with these compounds, which may have resulted in cell lysis.

Table 2.

Antimicrobial activity of active compounds (MIC, μmol/L).

| Actinomycin D | Actinomycin X2 | Collismycin A | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candida albicans ATCC 10231 | 3.19 | 25.21 | 7.26 |

| Aspergillus niger ATCC 16404 | 101.96 | 100.84 | 58.11 |

| Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC 96918 | 101.96 | 100.84 | 58.11 |

| Trichophyton rubrum ATCC 60836 | 101.96 | 100.84 | 58.11 |

Fig. 4.

Scanning electron microscopy images of C. albicans treated and untreated with pure compounds. A & E Untreated C. albicans. B & F Actinomycin X2-treated C. albicans. C& G Actinomycin D-treated C. albicans. D & H Collismycin A-treated C. albicans.

3.5. Molecular docking studies

In this study, molecular docking analysis was conducted to evaluate the potential binding affinity of Actinomycin D, Actinomycin X2, and Collismycin A to selected receptors. The receptors selected were N-myristoyltransferase, dihydrofolate reductase, Secreted aspartic proteinase 5, 1,3-Beta-Glucanase, lanosterol 14-alpha demethylase, chitin Synthase 2, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase, thymidylate synthase, and squalene epoxidase (Table 3). The results showed that Actinomycin D and Actinomycin X2 exhibited the highest affinity towards 1,3-Beta-glucanase with binding free energies ranging between −89.088 and −129.82 kcal/mol, and −78.579 and −118.283 kcal/mol, respectively. Collismycin A, on the other hand, showed the highest affinity towards Chitin Synthase 2 with a binding free energy of −94.578 kcal/mol, followed by squalene epoxidase (−86.692 kcal/mol), and 1,3-Beta-glucanase (−81.002 kcal/mol). These results suggest that Actinomycin D, Actinomycin X2, and Collismycin A have the potential to target these receptors and may be useful as antifungal agents.

Table 3.

Molecular docking analysis between Actinomycin D, Actinomycin X2, and Collismycin A with receptors.

| Receptors | ID | Docking predicted binding energy (Kcal/mol) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinomycin D | Actinomycin X2 | Collismycin A | ||

| N-myristoyltransferase | 1IYL | −97.636 | −93.728 | −79.694 |

| Dihydrofolate reductase | 1M78 | −96.225 | −93.095 | −78.085 |

| Secreted aspartic proteinase 5 | 2QZX | −89.088 | −78.579 | −59.835 |

| 1,3-Beta-Glucanase | 4M80 | −129.824 | −118.283 | −81.002 |

| Lanosterol 14-alpha demethylase | 5V5Z | −101.023 | −86.989 | −73.011 |

| Chitin Synthase 2 | 6LNK | −127.663 | −105.582 | −94.578 |

| Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase | 7V6F | −99.196 | −99.637 | −66.599 |

| Thymidylate synthase | P12461 | −124.139 | −106.425 | −70.1723 |

| Squalene epoxidase | Q92206 | −99.508 | −102.384 | −86.692 |

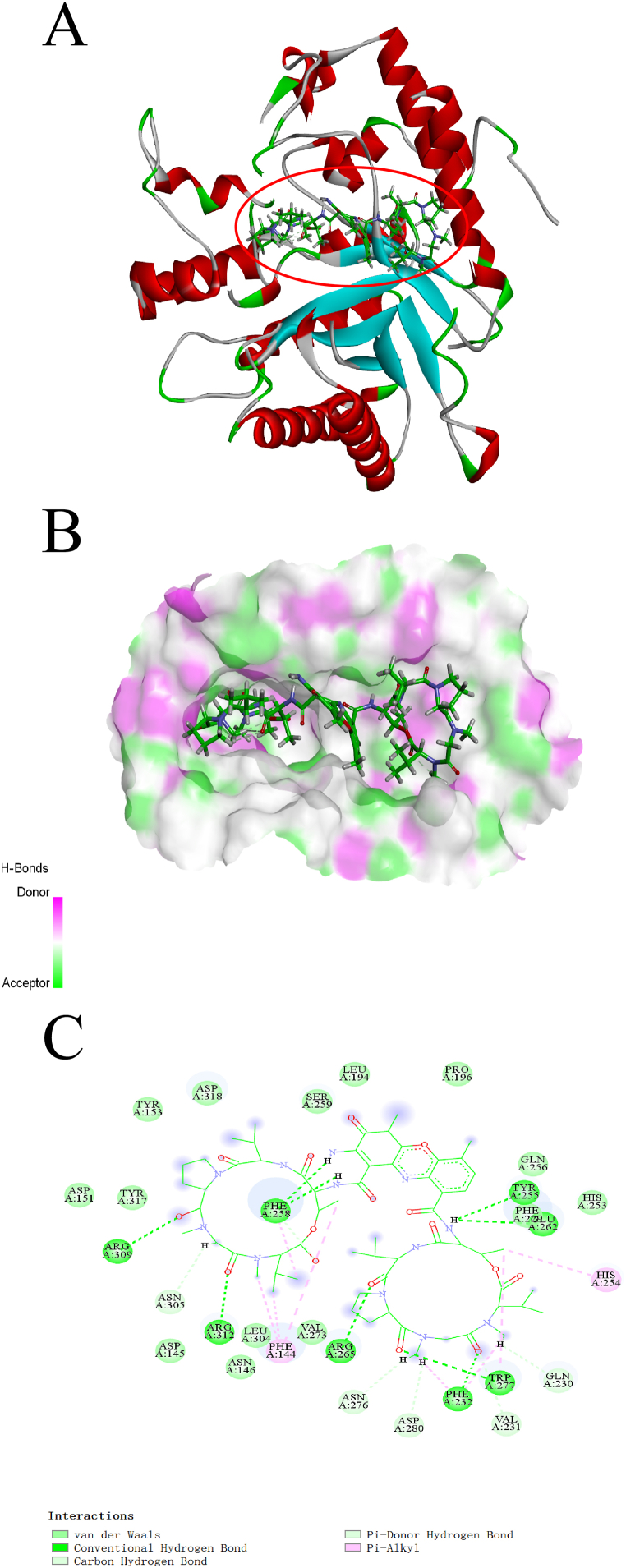

We also provided visual representations of the interaction between these compounds and their respective receptors in Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7AB, as well as detailed information about the intermolecular interactions in Table S1. The stability of the interactions was mainly due to the formation of H-bonds and hydrophobic interactions between the compounds and the receptor active sites. At 1,3-Beta-glucanase, Actinomycin D formed nine conventional H-bonds, five carbon H-bonds, and two hydrophobic interactions, while Actinomycin X2 formed four conventional H-bonds, four carbon H-bonds, and seven hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 5C). The researchers also noted that although Actinomycin D and Actinomycin X2 have a slight difference in chemical structure, the two compounds only have six same interactions (Fig. 6C). At Chitin Synthase 2, Collismycin A formed two carbon H-bonds with Tyr302 and Val303, and four hydrophobic interactions with Arg300, Arg300, Val303, and LysA306 (Fig. 7C). Overall, these findings suggest potential new targets for these compounds and provide insights for further drug design and development.

Fig. 5.

Binding complex and interaction visualization between 1,3-Beta-Glucanase (4M80) and Actinomycin D. A & B 3D interaction analyses of 1,3-Beta-Glucanase complexed with Actinomycin D. C 2D interactions analyses of 1,3-Beta-Glucanase complexed with Actinomycin D.

Fig. 6.

Binding complex and interaction visualization between 1,3-Beta-Glucanase (4M80) and Actinomycin X2. A & B 3D interaction analyses of 1,3-Beta-Glucanase complexed with Actinomycin X2. C 2D interactions analyses of 1,3-Beta-Glucanase complexed with Actinomycin X2.

Fig. 7.

Binding complex and interaction visualization between Chitin Synthase 2 (6LNK) and Collismycin A. A & B 3D interaction analyses of Chitin Synthase 2 complexed with Collismycin A. C 2D interactions analyses of Chitin Synthase 2 complexed with Collismycin A.

3.6. In-silico drug-likeness and ADMET prediction of bioactive compounds

In this study, Lipinski's rule of five was used to predict the drug-like properties of the bioactive compounds. According to Lipinski's rule of five, a molecule that is most likely to be developed as a candidate for an orally active medication should meet certain criteria, including a molecular weight less than 500 Da, no more than 10 hydrogen bonds, no more than 5 hydrogen H-Bond Donors, and MLogP<4.15. As shown in Table 4, the results indicate that Collismycin A complies with Lipinski's rule of five and can be strongly recommended as an oral drug.

Table 4.

Lipinski's rule of five analysis.

| Compounds | Molecular Formula | Lipinski's Parameters |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | MLogP | H-Bond Donor | H-Bond Acceptor | Violations | ||

| Actinomycin D | C62H86N12O16 | 1255.42 | −2.99 | 5 | 17 | 2 |

| Actinomycin X2 | C62H84N12O17 | 1269.40 | −3.74 | 5 | 18 | 2 |

| Collismycin A | C13H13N3O2S | 275.33 | 0.47 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

Pharmacokinetics refers to how a drug behaves after it is introduced into the body, with ADMET parameters being the factors influencing its pharmacokinetics. The ADMET parameters of the bioactive compounds in silico were presented in Table 5. Caco2 permeability of all compounds was above 0.9, which indicates that the compounds can be administered orally. The blood-brain barrier (BBB) plays a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis in the central nervous system (CNS) by preventing unrestricted movement of poisonous or harmful compounds, transit of nutrients, and removal of metabolites from the brain. However, both compounds cannot cross into the brain as their BBB permeability was above 0.3. Actinomycin D and Actinomycin X2 have a class II acute oral toxicity, which means they are fatal if swallowed, with LD50 values between 5 and 50 mg/kg, while Collismycin A has a class IV acute oral toxicity, which means it is harmful if swallowed, with LD50 values between 300 and 2000 mg/kg.

Table 5.

In silico ADMET properties of each compound.

| Parameters | Actinomycin D | Actinomycin X2 | Collismycin A |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption (A) | |||

| Caco2 permeability | 1.464 | 1.486 | 1.21 |

| Distribution (D) | |||

| BBB permeability (<-1) | −1.383 | −1.408 | −0.66 |

| Metabolism (M) | |||

| CYP1A2 inhibitor | No | No | No |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | No | No | No |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor | No | No | No |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | No | No | No |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | No | No | No |

| Excretion (E) | |||

| Clearance | −1.374 | −1.448 | 0.757 |

| Renal OCT2 substrate | No | No | No |

| Toxicity (T) | |||

| Cytotoxicity | Yes | Yes | No |

| AMES toxicity | No | No | No |

| Hepatotoxicity | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Skin Sensitisation | No | No | No |

| Oral Toxicity (LD50) (mg/kg) | 7 | 7 | 1000 |

| Acute oral toxicity | Class II | Class II | Class IV |

4. Discussion

Rare actinomycetes have recently gained popularity in research, and several valuable compounds have been discovered from them [36]. Examples include vancomycin from Amycolatopsis [37], macrolides from Micromonospora [38], and erythromycin from Saccharopolyspora [39]. Gordonia is a member of the rare actinomycetes family that can be found in various environments such as the human body, soil, sewage, and oil wells [40]. However, it is rarely found in insects. In this study, 15 strains of Gordonia were isolated from the gut of P. americana for the first time, which provides new sources of Gordonia.

Insects are the largest group in nature and they harbor a large number of symbiotic bacteria in their bodies. It has been suggested by many researchers that gut-inhabiting bacteria protect their insect hosts against pathogens by synthesizing specific antimicrobial compounds [[41], [42], [43]]. For instance, Nurdjannah et al. found that Bacillus cereus from Apis dorsata gut produced surfactin, fengycin, and iturin A that exhibited potent anti-Neisseria gonorrhoeae activity [44]. Pleosporales sp. BYCDW4 from Odontotermes formosanus produced 5-hydroxyramulosin and biatriosporin M, which showed strong antibacterial effects against E. coli, C. albicans, B. subtilis, and S. aureus [45]. It is widely acknowledged that microorganisms isolated from insects are crucial sources for discovering and producing bioactive compounds.

The microbiomes of insects hold great promise for developing new antibiotics to treat fungal infections. In a study by MG Chevrette et al., insect-associated actinomycetes showed significantly greater activity against fungi and a wider range of biosynthetic capabilities compared to soil-associated actinomycetes, as determined through ecologically optimized bioassays, genomic, and metabolomic analyses [46]. While previous studies have not reported the anti-fungal activity of Gordonia isolated from different environments, our research found that 53.3% of Gordonia strains isolated from the gut of P. americana exhibited anti-fungal effects. This discovery highlights a new source of microorganisms for exploring novel natural anti-fungal products.

Out of all the isolates, WA8-44 showed robust anti-fungal activity against common human pathogens. Therefore, WA8-44 was selected for further investigation. Through morphological characteristics, molecular identification, and 16 S rRNA phylogenetic tree analysis, WA8-44 was identified as Gordonia terrae (GenBank Accession Number: MH605445). Using bioassay-guided isolation methods, three active anti-fungal compounds were separated from the fermentation broth of WA8-44. The purified compounds were chemically characterized through MS, 1H NMR, and 13C NMR. The three active anti-fungal compounds were identified as Collismycin A, Actinomycin D, and Actinomycin X2.

Collismycin A is a natural product that is known to have cytotoxic activity against cancer cells and is typically produced only by Streptomyces [47]. However, our study discovered that Gordonia also produces Collismycin A, which showed remarkable activity against fungi. While previous studies have not reported the anti-filamentous fungi activity of Collismycin A, our findings reveal its potential as an effective anti-filamentous fungi agent. Additionally, Actinomycin D and Actinomycin X2, two chromopeptide lactone antibiotics with various biological activities, including anti-cancer [48], anti-bacterial, anti-fungal [49], and anti-leishmanial properties [50], were also identified in Gordonia. These compounds are typically produced by Streptomyces [51] and, in some cases, Micromonospora [52], but this study demonstrated that they can also be produced by Gordonia. The MIC assay showed that all three active compounds had significant anti-fungal activity against C. albicans, T. rubrum, A. fumigatus, and A. niger, with MICs ranging from 3.19–101.96 μmol/L.

Molecular docking is a powerful computational method used to predict the binding affinities and conformations of drug candidates [53,54]. In this study, in-silico virtual screening was employed to determine the mechanism of action of three antifungal bioactive compounds derived from Gordonia sp. WA8-44 against C. albicans. Nine modeled protein targets from C. albicans were docked with the bioactive compounds, and the results showed that Actinomycin D and Actinomycin X2 were the most potent against 1,3Beta-Glucanase. This protein is a potential therapeutic target for treating Candida infections because it is responsible for most of the glucanase activity in the Candida cell wall [55]. Although Actinomycin X2 and Actinomycin D are similar in chemical structure, Actinomycin D exhibited stronger anti-C. albicans activity due to its six additional H-bonding interactions with 1,3Beta-Glucanase [56]. Likewise, in the Hamdoon's study, methylated taxifolin demonstrated enhanced binding affinity towards various pro- and antiapoptotic proteins compared to taxifolin, thereby displaying heightened anticancer efficacy [57]. Although previous studies have reported the anti-Candida albicans effect of Collismycin A, its mechanism of action is still unclear [58]. In Candida albicans, Chitin Synthase II is primarily responsible for synthesizing the primary septum and is considered a potential target for antifungal drugs [59]. These results provide insights into the possible specific mechanisms of action of these compounds and could guide future experimental investigations.

Drug development is a time-consuming and costly process, and inadequate pharmacokinetics is a significant cause of failure in clinical trials [60]. Therefore, ADME data, which provide information on a drug's absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion, are becoming increasingly crucial in drug development. In-silico techniques offer a cost-effective way to filter and optimize drug candidates in the early stages of drug development since experimental acquisition of ADME data can be expensive. In this study, an in-silico assessment of the ADME properties of the three bioactive compounds was conducted. The Caco2 permeability values of all compounds were greater than 0.9, suggesting their suitability for oral administration. The BBB permeability of all three substances was low, indicating that none of them would have any significant negative impact on the central nervous system. In the metabolic process of drugs, CYP enzymes, including CYP450 inhibitors, play a central role. None of the three drugs were predicted to inhibit P450, indicating that they would not present drug-drug interaction problems with medications targeting those CYP enzymes. Consistent with previous reports in the literature, Actinomycin D and Actinomycin X2 were predicted to have moderate toxicity [48]. The results obtained from the in-silico ADMET studies predicts Collismycin A as a potent oral drug candidate due to its low toxicity and compliance with the Lipinski rule of five.

This study represents the first attempt to isolate anti-fungal secondary metabolites from Gordonia associated with P. americana. A total of 15 strains of Gordonia were isolated from the gut of P. americana, and 53.3% of them exhibited anti-fungal activity. Among these strains, three anti-fungal compounds (Collismycin A, actinomycin D, and actinomycin X2) were identified and purified from the secondary metabolites of Gordonia sp. WA8-44. Notably, Collismycin A was isolated from Gordonia for the first time, and its anti-filamentous fungi activity was firstly identified in this study. Based on the predicted ADMET properties, Collismycin A demonstrated good oral bioavailability and low toxicity, making it a promising candidate for the development of orally active drugs.

Author contribution statement

Wenbin liu, Ph.D.; Xiaobao Jin: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Ertong Li: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Lingyan Liu; Fangyuan Tian; Xiongming luo; Yanqu Cai: Performed the experiments.

Jie Wang: Conceived and designed the experiments.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. Material/referenced in article.

Additional information

Supplementary content related to this article has been published online at [URL].

Funding statement

This work was funded by the Guangzhou Science and technology planning project (No. 202201010357), the Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (No. 2020A1515011097), the Public Welfare Research and Capacity Building Project of Guangdong Province (2017A020211008), and the Key Projects of Basic Research and Applied Basic Research of Guangdong Province Normal University (No. 2018KZDXM041).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17777.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Jenks J.D., Cornely O.A., Chen S.C., Thompson G.R., 3rd, Hoenigl M. Breakthrough invasive fungal infections: who is at risk? Mycoses. 2020;63(10):1021–1032. doi: 10.1111/myc.13148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pristov K.E., Ghannoum M.A. Resistance of Candida to azoles and echinocandins worldwide. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019;25(7):792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rathod B.B., Korasapati R., Sripadi P., Reddy Shetty P. Novel actinomycin group compound from newly isolated Streptomyces sp. RAB12: isolation, characterization, and evaluation of antimicrobial potential. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018;102(3):1241–1250. doi: 10.1007/s00253-017-8696-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alharthi M.N., Ismail I., Bellucci S., Jaremko M., Abo-Aba S.E.M., Abdel Salam M. Biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles using ziziphus jujube plant extract assisted by ultrasonic irradiation and their biological applications. Separations. 2023;10(2):78. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katz L., Baltz R.H. Natural product discovery: past, present, and future. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016;43(2–3):155–176. doi: 10.1007/s10295-015-1723-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah A.M., Shakeel U.R., Hussain A., Mushtaq S., Rather M.A., Shah A., Ahmad Z., Khan I.A., Bhat K.A., Hassan Q.P. Antimicrobial investigation of selected soil actinomycetes isolated from unexplored regions of Kashmir Himalayas, India. Microb. Pathog. 2017;110:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacob C., Weissman K.J. Unpackaging the roles of Streptomyces natural products. Cell Chem. Biol. 2017;24(10):1194–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Fadhli A.A., Threadgill M.D., Mohammed F., Sibley P., Al-Ariqi W., Parveen I. Macrolides from rare actinomycetes: structures and bioactivities. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2022;59(2) doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2022.106523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andalibi F., Gordonia Fatahi-Bafghi M. Isolation and identification in clinical samples and role in biotechnology. Folia Microbiol. 2017;62(3):245–252. doi: 10.1007/s12223-017-0491-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J., Zhan P., Koopman Ben, Fang G., Shi Y. Bioaugmentation with Gordonia strain JW8 in treatment of pulp and paper wastewater. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy. 2012;14(5):899–904. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tatangelo V., Mangili I., Caracino P., Anzano M., Najmi Z., Bestetti G., Collina E., Franzetti A., Lasagni M. Biological devulcanization of ground natural rubber by Gordonia desulfuricans DSM 44462(T) strain. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016;100(20):8931–8942. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7691-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider K., Graf E., Irran E., Nicholson G., Stainsby F.M., Goodfellow M., Borden S.A., Keller S., Süssmuth R.D., Fiedler H.P. Bendigoles A approximately C, new steroids from Gordonia australis Acta 2299. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 2008;61(6):356–364. doi: 10.1038/ja.2008.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graça A.P., Bondoso J., Gaspar H., Xavier J.R., Monteiro M.C., de la Cruz M., Oves-Costales D., Vicente F., Lage O.M. Antimicrobial activity of heterotrophic bacterial communities from the marine sponge Erylus discophorus (Astrophorida, Geodiidae) PLoS One. 2013;8(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park H.B., Park J.S., Lee S.I., Shin B., Oh D.C., Kwon H.C. Gordonic acid, a polyketide glycoside derived from bacterial coculture of Streptomyces and Gordonia species. J. Nat. Prod. 2017;80(9):2542–2546. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng C., Liao Q., Hu Y., Shen Y., Geng F., Chen L. The role of Periplaneta americana (blattodea: blattidae) in modern versus traditional Chinese medicine. J. Med. Entomol. 2019;56(6):1522–1526. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjz081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amer A., Hamdy B., Mahmoud D., Elanany M., Rady M., Alahmadi T., Alharbi S., AlAshaal S. Antagonistic activity of bacteria isolated from the Periplaneta americana L. Gut against some multidrug-resistant human pathogens. Antibiotics. 2021;10(3):294. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10030294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang X., Shen J., Wang J., Chen Z.L., Lin P.B., Chen Z.Y., Liu L.Y., Zeng H.X., Jin X.B. Antifungal activity of 3-acetylbenzamide produced by actinomycete WA23-4-4 from the intestinal tract of Periplaneta americana. J. Microbiol. 2018;56(7):516–523. doi: 10.1007/s12275-018-7510-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma Y., Xu M., Liu H., Yu T., Guo P., Liu W., Jin X. Antimicrobial compounds were isolated from the secondary metabolites of Gordonia, a resident of intestinal tract of Periplaneta americana. Amb. Express. 2021;11(1):111. doi: 10.1186/s13568-021-01272-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Z., Ou P., Liu L., Jin X. Anti-MRSA activity of actinomycin X(2) and Collismycin A produced by Streptomyces globisporus WA5-2-37 from the intestinal tract of American cockroach (Periplaneta americana) Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:555. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J., Liu H., Zhu L., Wang J., Luo X., Liu W., Ma Y. Prodigiosin from Serratia marcescens in cockroach inhibits the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. Molecules. 2022;27(21):7281. doi: 10.3390/molecules27217281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lima S.M., Melo J.G., Militão G.C., Lima G.M., do Carmo A.L.M., Aguiar J.S., Araújo R.M., Braz-Filho R., Marchand P., Araújo J.M., Silva T.G. Characterization of the biochemical, physiological, and medicinal properties of Streptomyces hygroscopicus ACTMS-9H isolated from the Amazon (Brazil) Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017;101(2):711–723. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7886-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vieira P.M., Santos M.P., Andrade C.M., Souza-Neto O.A., Ulhoa C.J., Aragão F.J.L. Overexpression of an aquaglyceroporin gene from Trichoderma harzianum improves water-use efficiency and drought tolerance in Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017;121:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altinbaş R., Barış A., Şen S., Öztürk R., Kiraz N. Comparison of the Sensititre YeastOne antifungal method with the CLSI M27-A3 reference method to determine the activity of antifungal agents against clinical isolates of Candidaspp. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020;50(8):2024–2031. doi: 10.3906/sag-1909-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang W., Bao F., Wang Z., Liu H., Zhang F. Comparison of the Sensititre YeastOne(®) and CLSI M38-A2 microdilution methods in determining the activity of nine antifungal agents against dermatophytes. Mycoses. 2021;64(7):734–741. doi: 10.1111/myc.13272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeyanthi V., Anbu P., Vairamani M., Velusamy P. Isolation of hydroquinone (benzene-1,4-diol) metabolite from halotolerant Bacillus methylotrophicus MHC10 and its inhibitory activity towards bacterial pathogens. Bioproc. Biosyst. Eng. 2016;39(3):429–439. doi: 10.1007/s00449-015-1526-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ikonomova S.P., Moghaddam-Taaheri P., Jabra-Rizk M.A., Wang Y., Karlsson A.J. Engineering improved variants of the antifungal peptide histatin 5 with reduced susceptibility to Candida albicans secreted aspartic proteases and enhanced antimicrobial potency. FEBS J. 2018;285(1):146–159. doi: 10.1111/febs.14327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marin V., Iturra A., Opazo A., Schmidt B., Heydenreich M., Ortiz L., Jiménez V.A., Paz C. Oxidation of isodrimeninol with PCC yields drimane derivatives with activity against Candida yeast by inhibition of lanosterol 14-alpha demethylase. Biomolecules. 2020;10(8):1101. doi: 10.3390/biom10081101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han X., Zhu X., Hong Z., Wei L., Ren Y., Wan F., Zhu S., Peng H., Guo L., Rao L., Feng L., Wan J. Structure-based rational design of novel inhibitors against fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase from Candida albicans. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017;57(6):1426–1438. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qureshi K.A., Imtiaz M., Parvez A., Rai P.K., Jaremko M., Emwas A.H., Bholay A.D., Fatmi M.Q. In vitro and in silico approaches for the evaluation of antimicrobial activity, time-kill kinetics, and anti-biofilm potential of thymoquinone (2-methyl-5-propan-2-ylcyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione) against selected human pathogens. Antibiotics. 2022;11(1):79. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11010079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prajapati J., Goswami D., Dabhi M., Acharya D., Rawal R.M. Potential dual inhibition of SE and CYP51 by eugenol conferring inhibition of Candida albicans: computationally curated study with experimental validation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022;151(Pt A) doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.106237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsu K.C., Chen Y.F., Lin S.R., Yang J.M. iGEMDOCK: a graphical environment of enhancing GEMDOCK using pharmacological interactions and post-screening analysis. BMC Bioinf. 2011;12(Suppl 1):S33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-S1-S33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Viana Nunes A.M., das Chagas Pereira de Andrade F., Filgueiras L.A., de Carvalho Maia O.A., Cunha R., Rodezno S.V.A., Maia Filho A.L.M., de Amorim Carvalho F.A., Braz D.C., Mendes A.N. preADMET analysis and clinical aspects of dogs treated with the Organotellurium compound RF07: a possible control for canine visceral leishmaniasis? Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020;80 doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2020.103470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pires D.E., Blundell T.L., Ascher D.B. pkCSM: predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58(9):4066–4072. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banerjee P., Eckert A.O., Schrey A.K., Preissner R. ProTox-II: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W257–w263. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Subramani R., Sipkema D. Marine rare actinomycetes: a promising source of structurally diverse and unique novel natural products. Mar. Drugs. 2019;17(5):249. doi: 10.3390/md17050249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang C.Z., Zhang Z., Anderson S., Yuan C.S. Natural products and chemotherapeutic agents on cancer: prevention vs. treatment. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2014;42(6):1555–1558. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X1420002X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laakso J.A., Mocek U.M., Van Dun J., Wouters W., Janicot M. R176502, a new bafilolide metabolite with potent antiproliferative activity from a novel Micromonospora species. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 2003;56(11):909–916. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.56.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li X., Chen J., Andersen J.M., Chu J., Jensen P.R. Cofactor engineering redirects secondary metabolism and enhances erythromycin production in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. ACS Synth. Biol. 2020;9(3):655–670. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan C., Kuranaga T., Liu C., Lu S., Shinzato N., Kakeya H., Thioamycolamides A.-E. Sulfur-containing cycliclipopeptides produced by the rare actinomycete Amycolatopsis sp. Org. Lett. 2020;22(8):3014–3017. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c00776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grubbs K.J., Surup F., Biedermann P.H.W., McDonald B.R., Klassen J.L., Carlson C.M., Clardy J., Currie C.R. Cycloheximide-producing Streptomyces associated with Xyleborinus saxesenii and Xyleborus affinis fungus-farming ambrosia beetles. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.562140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ellegaard K.M., Engel P. Genomic diversity landscape of the honey bee gut microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2019;10(1):446. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08303-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benndorf R., Guo H., Sommerwerk E., Weigel C., Garcia-Altares M., Martin K., Hu H., Küfner M., de Beer Z.W., Poulsen M., Beemelmanns C. Natural products from actinobacteria associated with fungus-growing termites. Antibiotics. 2018;7(3):83. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics7030083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niode N.J., Adji A., Rimbing J., Tulung M., Alorabi M., El-Shehawi A.M., Idroes R., Celik I., Fatimawali, Adam A.A., Dhama K., Mostafa-Hedeab G., Mohamed A.A., Tallei T.E., Emran T.B. In silico and in vitro evaluation of the antimicrobial potential of Bacillus cereus isolated from Apis dorsata gut against Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antibiotics. 2021;10(11):1401. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10111401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu X., Shao M., Yin C., Mao Z., Shi J., Yu X., Wang Y., Sun F., Zhang Y. Diversity, bacterial symbionts, and antimicrobial potential of termite-associated fungi. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:300. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chevrette M.G., Carlson C.M., Ortega H.E., Thomas C., Ananiev G.E., Barns K.J., Book A.J., Cagnazzo J., Carlos C., Flanigan W., Grubbs K.J., Horn H.A., Hoffmann F.M., Klassen J.L., Knack J.J., Lewin G.R., McDonald B.R., Muller L., Melo W.G.P., Pinto-Tomás A.A., Schmitz A., Wendt-Pienkowski E., Wildman S., Zhao M., Zhang F., Bugni T.S., Andes D.R., Pupo M.T., Currie C.R. The antimicrobial potential of Streptomyces from insect microbiomes. Nat. Commun. 2019;10(1):516. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08438-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shindo K., Yamagishi Y., Okada Y., Kawai H., Collismycins A. Novel non-steroidal inhibitors of dexamethasone-glucocorticoid receptor binding. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1994;47(9):1072–1074. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.47.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lamture G., Crooks P.A., Borrelli M.J. Actinomycin-D and dimethylamino-parthenolide synergism in treating human pancreatic cancer cells. Drug Dev. Res. 2018;79(6):287–294. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zeng H., Feng P.X., Wan C.X. Antifungal effects of actinomycin D on Verticillium dahliae via a membrane-splitting mechanism. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019;33(12):1751–1755. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2018.1431630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qureshi K.A., Al Nasr I., Koko W.S., Khan T.A., Fatmi M.Q., Imtiaz M., Khan R.A., Mohammed H.A., Jaremko M., Emwas A.H., Azam F., Bholay A.D., Elhassan G.O., Prajapati D.K. In vitro and in silico approaches for the antileishmanial activity evaluations of actinomycins isolated from novel Streptomyces smyrnaeus strain UKAQ_23. Antibiotics. 2021;10(8):887. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10080887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peng F., Zhang M.Y., Hou S.Y., Chen J., Wu Y.Y., Zhang Y.X. Insights into Streptomyces spp. isolated from the rhizospheric soil of Panax notoginseng: isolation, antimicrobial activity and biosynthetic potential for polyketides and non-ribosomal peptides. BMC Microbiol. 2020;20(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12866-020-01832-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wagman G.H., Marquez J.A., Watkins P.D., Gentile F., Murawski A., Patel M., Weinstein M.J. A new actinomycin complex produced by a Micromonospora species: fermentation, isolation, and characterization. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1976;9(3):465–469. doi: 10.1128/aac.9.3.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pinzi L., Rastelli G. Molecular docking: shifting paradigms in drug discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(18):4331. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kijewska M., Sharfalddin A.A., Jaremko Ł., Cal M., Setner B., Siczek M., Stefanowicz P., Hussien M.A., Emwas A.H., Jaremko M. Lossen rearrangement of p-toluenesulfonates of N-oxyimides in basic condition, theoretical study, and molecular docking. Front. Chem. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.662533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cutfield S.M., Davies G.J., Murshudov G., Anderson B.F., Moody P.C., Sullivan P.A., Cutfield J.F. The structure of the exo-beta-(1,3)-glucanase from Candida albicans in native and bound forms: relationship between a pocket and groove in family 5 glycosyl hydrolases. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;294(3):771–783. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cseke A., Schwarz T., Jain S., Decker S., Vogl K., Urban E., Ecker G.F. Propafenone analogue with additional H-bond acceptor group shows increased inhibitory activity on P-glycoprotein. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim) 2020;353(3) doi: 10.1002/ardp.201900269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mohammed H.A., Almahmoud S.A., El-Ghaly E.M., Khan F.A., Emwas A.H., Jaremko M., Almulhim F., Khan R.A., Ragab E.A. Comparative anticancer potentials of taxifolin and quercetin methylated derivatives against HCT-116 cell lines: effects of O-methylation on taxifolin and quercetin as preliminary natural leads. ACS Omega. 2022;7(50):46629–46639. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c05565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stadler M., Bauch F., Henkel T., Mühlbauer A., Müller H., Spaltmann F., Weber K. Antifungal actinomycete metabolites discovered in a differential cell-based screening using a recombinant TOPO1 deletion mutant strain. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim) 2001;334(5):143–147. doi: 10.1002/1521-4184(200105)334:5<143::aid-ardp143>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walker L.A., Munro C.A., de Bruijn I., Lenardon M.D., McKinnon A., Gow N.A. Stimulation of chitin synthesis rescues Candida albicans from echinocandins. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Daoud N.E., Borah P., Deb P.K., Venugopala K.N., Hourani W., Alzweiri M., Bardaweel S.K., Tiwari V. ADMET profiling in drug discovery and development: perspectives of in silico, in vitro and integrated approaches. Curr. Drug Metabol. 2021;22(7):503–522. doi: 10.2174/1389200222666210705122913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supp. Material/referenced in article.