Abstract

Our aim was to investigate the association between gut microbiota and delirium occurrence in acutely ill older adults. We included 133 participants 65+ years consecutively admitted to the emergency department of a tertiary university hospital, between September 2019 and March 2020. We excluded candidates with ≥24-hour antibiotic utilization on admission, recent prebiotic or probiotic utilization, artificial nutrition, acute gastrointestinal disorders, severe traumatic brain injury, recent hospitalization, institutionalization, expected discharge ≤48 hours, or admission for end-of-life care. A trained research team followed a standardized interview protocol to collect sociodemographic, clinical, and laboratory data on admission and throughout the hospital stay. Our exposure measures were gut microbiota alpha and beta diversities, taxa relative abundance, and core microbiome. Our primary outcome was delirium, assessed twice daily using the Confusion Assessment Method. Delirium was detected in 38 participants (29%). We analyzed 257 swab samples. After adjusting for potential confounders, we observed that a greater alpha diversity (higher abundance and richness of microorganisms) was associated with a lower risk of delirium, as measured by the Shannon (odds ratio [OR] = 0.77; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.60–0.99; p = .042) and Pielou indexes (OR = 0.69; 95% CI = 0.51–0.87; p = .005). Bacterial taxa associated with pro-inflammatory pathways (Enterobacteriaceae) and modulation of relevant neurotransmitters (Serratia: dopamine; Bacteroides, Parabacteroides: GABA) were more common in participants with delirium. Gut microbiota diversity and composition were significantly different in acutely ill hospitalized older adults who experienced delirium. Our work is an original proof-of-concept investigation that lays a foundation for future biomarker studies and potential therapeutic targets for delirium prevention and treatment.

Keywords: Consciousness disorders, Hospitalization, Microbiome

The gut microbiome represents the nature, genome, and surrounding environment of microorganisms inhabiting the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract (1). Disturbances in the gut microbiome (ie, gut dysbiosis) increase with age and have been linked to relevant conditions, particularly obesity, insulin resistance, and inflammatory bowel disease (2).

Gut dysbiosis has also been studied in chronic neuropsychiatric diseases such as depression and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (3–7). Patients with the major depressive disorder appear to have a different gut microbial composition from healthy controls, with significant changes in the relative abundance of their bacterial phyla (8). Similar findings have been described in patients with AD, with a lower abundance of specific bacteria groups and a diversity of microorganisms distinct from healthy controls (5). Despite these findings in chronic neuropsychiatric disorders, data on gut dysbiosis in more acute conditions are lacking.

Delirium is the most frequent acute neuropsychiatric complication in hospitalized older adults and is characterized by inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered consciousness, features that often fluctuate over time (9). Delirium is associated with several adverse outcomes, including functional and cognitive decline, institutionalization, and death (10). Interestingly, delirium and gut dysbiosis share three fundamental characteristics: (a) higher prevalence in older adults; (b) association with complex and multifactorial conditions; and (c) biological pathways significantly influenced by inflammation, neuroendocrine dysregulation, and oxidative stress (10–14). We also know that despite being relatively stable under healthy circumstances, studies in critical patients have demonstrated that the gut microbiome can change during acute illnesses in just a few days (15). Therefore, it would be reasonable to expect that dynamic changes in microbial composition might be detected in the context of delirium.

Several delirium pathophysiological models have been proposed in recent years, but substantial gaps remain. Results from the growing field of microbiome research suggest that new insights might arise from investigating dysbiosis in delirium, with the potential identification of novel biomarkers and treatment pathways. To explore this hypothesis, our study aimed to investigate the association between gut microbiota diversity and composition and delirium occurrence in acutely ill older adults.

Method

Design, Setting, and Population

We prospectively screened for participation patients admitted to the Emergency Department (ED) of a tertiary university hospital between September 30, 2019, and March 17, 2020. Hospital das Clinicas is a 2 200-bed hospital located in São Paulo, Brazil, dedicated to the care of high-complexity medical and surgical patients. Admissions to its ED are centrally managed by the Regulatory Central of the State of São Paulo, and severely ill patients are preferably referred to the hospital.

Eligible patients were 65 years or older and hospitalized for less than 24 hours. We excluded candidates according to the following criteria: (a) antibiotic utilization for 24 hours or more on admission; (b) pre, pro, or symbiotics utilization in the 30 days preceding admission; (c) enteral or parenteral nutrition; (d) acute GI disorders (eg, acute diarrhea, GI bleeding, acute abdomen); (e) severe traumatic brain injury; (f) previous hospitalization in the 30 days preceding admission or institutionalization; (g) expected hospital discharge in 48 hours or less; and (h) hospitalization for end-of-life care.

The study was approved by the local institutional review board (CAPPESq, no. 006688019.0.0000.0068, February 7, 2019). We obtained written informed consent from all participants or their legal representatives and used REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) resources to secure and manage all study-related data (16).

Baseline Characteristics

Trained investigators completed the study interviews and assessments using standardized REDCap forms. We collected baseline sociodemographic and clinical data, including age, sex, literacy level, medical history, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) (17), nutritional status using the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) (18), polypharmacy (chronic use of 5 or more medications), admission diagnoses, and recent antibiotic utilization history. We performed functional and cognitive assessments, respectively scoring activities of daily living and the 10-point Cognitive Screener (10-CS) (19).

We further collected the following laboratory tests upon study inclusion: C-reactive protein, blood urea nitrogen, and inflammatory biomarkers (interleukin[IL]-6, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor[TNF]-α). We measured cytokine plasma levels using the magnetic bead immunoassay Milliplex and the MAGPIX System (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA).

Rectal Swab Samples

We obtained deep rectal swabs (Copan Liquid Amies Swab, ESwab, COPAN Italia) for gut microbiota sampling (20,21). Although stool samples are more commonly used for this purpose, the unpredictable nature of bowel movements would jeopardize timely sample collection, given the acute and fluctuating nature of delirium. Moreover, rectal swab samples provide comparable microbiota profiling to fecal analysis for the same individual (21).

Three registered nurses performed the sampling, which consisted of carefully inserting the rectal swab ≥2 cm past the external anal border, avoiding the perianal skin to prevent contamination, and completing a gentle 360° rotation. The procedure was completed in private examining rooms or screen-protected areas to preserve our participants’ privacy during the sample collection. Each swab was immediately placed in its original container with the preservation medium and stored at −20°C for up to 48 hours before being transferred to a −80°C freezer for long-term storage and further processing.

The sampling procedures were performed on inclusion (S1) and repeated 72 hours after inclusion (S2). Participants who were discharged or died within 72 hours of admission, or refused to provide additional samples, were not swabbed again. We obtained a third sample (S3) from participants who converted either from a negative to positive CAM (incident delirium) or from a positive to negative CAM (delirium resolution) after S2. Detailed sampling procedures can be found in Supplementary Figure 1.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was the overall occurrence of delirium based on the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) criteria. We completed the CAM algorithm (22) twice daily to detect delirium throughout hospital stay. Our standardized interview protocol incorporated a brief neuropsychiatric anamnesis, cognitive screening (10-CS), attention testing (days of the week backwards and vigilance A test) (23), level of consciousness assessment (Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale [RASS]) (24), and electronic medical record revisions.

Our raters attended training sessions before the study initiation, which included simulations and bedside evaluations, and we achieved high interrater reliability levels for CAM-based delirium diagnoses (>95%). Even so, whenever our raters were uncertain regarding the presence of delirium, two experienced physicians (FBG and JCGA) repeated or reviewed the assessments to adjudicate the final diagnosis.

Secondary outcomes included delirium duration (total of CAM-positive days), delirium severity as measured by the CAM-Severity (CAM-S) (25), and level of consciousness according to the RASS. We scored the CAM-S at each time point, with higher scores indicating greater severity. We also documented surgical procedures, admissions to intensive care, length of hospital stay, and in-hospital mortality.

Microbiota Analyses

We used q2-diversity to estimate microbiota diversity and summarized microbiota compositions as relative abundances of bacterial taxa (26). We reported alpha diversity, which analyzes microbial diversity within each community or sample, using the number of observed species, the Shannon index, and the Pielou index. We reported beta diversity, which analyzes the differences between two communities or samples, using the Bray-Curtis distance and the UniFrac test. For beta diversity estimation, we used principal coordinate analyses (PCoA) to visualize potential dissimilarities. We used permutational multivariable analyses of variance (PERMANOVA) to numerically compare beta-diversities across groups. We also estimated linear discriminant analysis effect sizes (LEfSe) (27), a validated method for class comparisons in metagenomic studies, to characterize relevant microbial differences between participants with and without delirium.

We explored the core microbiota, characterized by microorganisms (or groups of taxa) detected in the totality (CORE 100%) or most of the samples per group (CORE 75-80%). The core microbiota analyses were performed in the overall swab sample and in samples from participants with CAM conversion during hospital stay (either incident delirium or delirium resolution). In this subgroup, we categorized participants according to early (<72 hours) or late CAM conversion (≥72 hours).

Additional details of bioinformatics and microbiota analyses are described in the Supplementary Material. All microbiome terminology was thoroughly revised by experts and follows existing recommendations (1). Accordingly, the term microbiota was used along the text to represent our analysis restricted to bacterial communities, not including their surrounding environment. We further ascertained bacterial taxonomic information using the Integrated Taxonomic Information System online database (www.itis.gov).

Statistical Analyses

Continuous data were compared according to delirium occurrence using unpaired t-tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, and categorical data were analyzed using Pearson’s χ 2 tests or Fisher’s exact tests. We examined the association between microbiota measures (alpha diversity, beta diversity, and relative abundance of bacterial taxa) and our prespecified outcomes at two levels: (a) swabs and (b) participants.

In our primary analysis, we included the overall sample of swabs (S1, S2, and S3) to compare gut microbiota composition according to delirium occurrence (present vs absent), delirium severity (CAM-S score), and impaired consciousness (RASS score ≠0). These three outcomes fluctuate and are, therefore, variable in each participant. Since they are dependent observations, and multiple swab samples were collected per participant, the outcomes were evaluated concerning alpha diversity and relative abundance (at genus level) using generalized estimating equations (GEE) and generalized linear models. In these models, the participants defined clusters. The independent association between gut microbiota composition and binary outcomes (delirium and level of consciousness) was evaluated using logistic regression models based on GEE, while the severity of delirium by CAM-S was analyzed as a continuous variable.

In a secondary analysis, we used each participant’s baseline swab (S1) to explore the association between pre-admission microbiota composition and the following outcomes: incident delirium; delirium duration; delirium severity; and impaired consciousness. We used Wilcoxon’s rank-sum or Kruskal–Wallis tests for comparisons according to categorical outcomes and Spearman’s correlation coefficients to analyze alpha diversity indexes according to CAM-S scores and inflammatory biomarker levels (IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α).

We also performed post hoc interaction analyses to explore whether nutritional status or antibiotic use, relevant contributors for both delirium occurrence and microbiota disturbances, might modify our principal findings. We grouped the 133 participants according to baseline MNA categories (from best to worst: “without risk”; “at risk of malnutrition”; “malnutrition”) and antibiotic use at the study inclusion. In each subgroup, we calculated alpha diversity indexes (Shannon and Pielou) and relative abundances of specific taxa (the most predominant ones identified in our primary analysis). A p-value for interaction was reported when appropriate (28).

We used directed acyclic graphs to select our adjustment variables a priori (29). Our final multivariable models were adjusted for age, sex, CCI, and body mass index. We performed statistical analyses using Stata Version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), and all tests were 2-tailed, admitting alpha errors up to 5%. We further adjusted p-values for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg method, as appropriate. Relative abundance analyses and their graphical data were processed in the R environment version 4.0.2 (R Foundation For Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, available at http://www.r-project.org).

Results

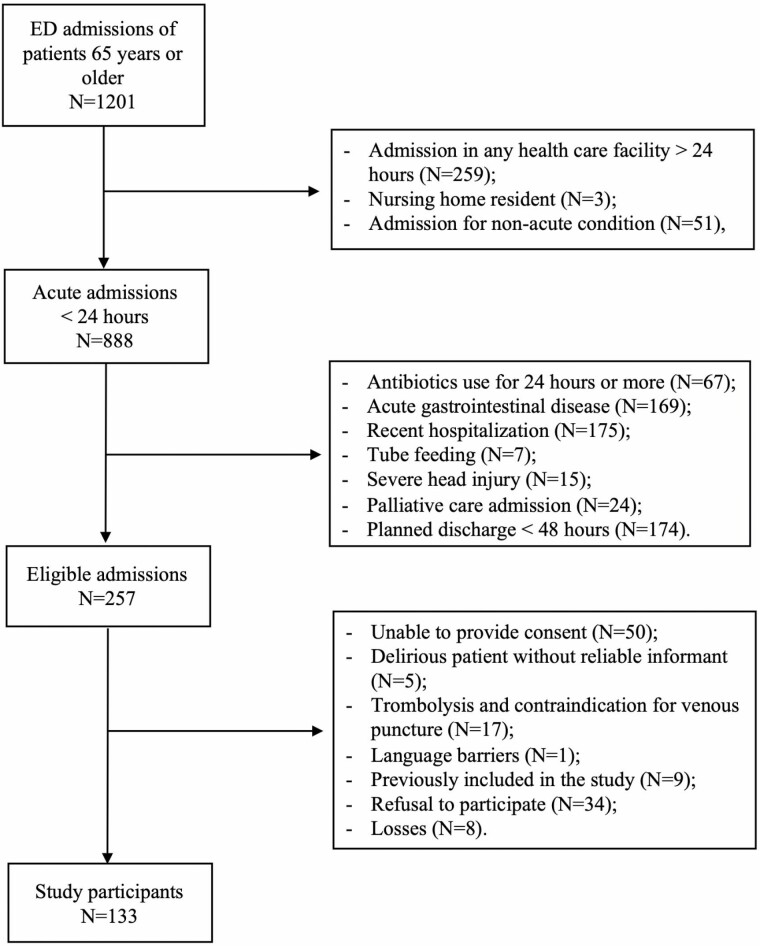

We included 133 participants (Table 1 and Figure 1). They were mostly male (56%), had a mean age of 75 (±8) years, and were hospitalized for a median 8 (5, 15) days. Overall, one-third of our sample had evidence of preexisting cognitive impairment, but this proportion reached 45% (N = 17) in participants who experienced delirium. We detected delirium in 38 individuals (29%)—19 on admission (prevalent delirium) and 19 during hospital stay (incident delirium). We observed that maximum CAM-S scores were 0 in 11% (N = 14) of our sample, 1–2 in 54% (N = 72), and 3–7 in 35% (N = 47). Delirium episodes had a median duration of 4 (2, 7) days. Surgical procedures, admission to intensive care units, and antibiotic utilization had a similar occurrence in delirium and non-delirium participants. Excepting TNF-α, inflammatory biomarkers had higher levels in the delirium group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Participants According to Delirium Occurrence

| Total | No delirium | Delirium | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 133 | N = 95 | N = 38 | ||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age range, No. (%), years | .001 | |||

| 65–74 | 74 (56) | 59 (62) | 15 (39) | |

| 75–84 | 40 (30) | 29 (31) | 11 (29) | |

| ≥85 | 19 (14) | 7 (7) | 12 (32) | |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 75 (8) | 73 (7) | 78 (9) | .002 |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 74 (56) | 54 (57) | 20 (52) | .66 |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 5 (4) | 6 (5) | 5 (4) | .34 |

| Baseline clinical characteristics | ||||

| Admission diagnosis, No. (%) | .70 | |||

| Cardiovascular | 47 (35) | 34 (36) | 13 (34) | |

| Sepsis/infection | 33 (25) | 21 (22) | 12 (32) | |

| Neurological* | 25 (19) | 19 (20) | 6 (16) | |

| Others | 28 (21) | 21 (22) | 7 (18) | |

| Antibiotics on inclusion (<24 hours), No. (%) | 15 (11) | 10 (11) | 5 (13) | .66 |

| CCI, median (IQR) | 1 (0, 3) | 1 (0, 3) | 1 (0, 3) | .53 |

| Cognitive decline, No. (%) | 44 (33) | 27 (28) | 17 (45) | .07 |

| Polypharmacy, No. (%) | 51 (38) | 35 (37) | 16 (42) | .57 |

| Visual impairment, No. (%) | 108 (81) | 80 (84) | 28 (74) | .16 |

| Hearing impairment, No. (%) | 22 (16) | 15 (16) | 7 (18) | .71 |

| Bladder catheterization, No. (%) | 48 (36) | 30 (32) | 18 (47) | .08 |

| Functional status, No. (%) | .04 | |||

| Dependent | 6 (4) | 3 (3) | 3 (8) | |

| Partially dependent | 25 (19) | 14 (15) | 11 (29) | |

| Independent | 102 (77) | 78 (82) | 24 (63) | |

| Nutritional status, No. (%) | .001 | |||

| Without risk | 24 (18) | 20 (21) | 4 (11) | |

| At-risk for malnutrition | 60 (45) | 50 (53) | 10 (26) | |

| Malnutrition | 49 (37) | 25 (26) | 24 (63) | |

| Baseline laboratory results | ||||

| BUN, median (IQR), mg/dL | 23 (16, 38) | 22 (16, 34) | 26 (15, 43) | .33 |

| CRP, median (IQR), mg/dL | 37 (8, 32) | 35 (7, 70) | 41 (9, 134) | .15 |

| IL-6, median (IQR), pg/mL | 5.7 (2.2, 17.0) | 4.3 (1.9, 15.6) | 10.8 (2.9, 47.1) | .024 |

| IL-10, median (IQR), pg/mL | 3.2 (1.6, 9.9) | 2.9 (1.6, 8.1) | 5.5 (1.9, 15.2) | .10 |

| TNF-α, median (IQR), pg/mL | 8.1 (4.9, 15.6) | 8.4 (5.5, 14.8) | 7.1 (3.8, 22.7) | .46 |

| Hospital outcomes | ||||

| ICU admission, No. (%) | 46 (35) | 29 (31) | 17 (45) | .12 |

| Antibiotic utilization, No. (%) | 69 (52) | 46 (48) | 23 (61) | .21 |

| Surgical procedures, No. (%) | 40 (30) | 27 (28) | 13 (34) | .51 |

| Length of stay, median (IQR), days | 8 (5, 15) | 8 (4, 13) | 14 (6, 32) | .003 |

| Death | 21 (16) | 8 (8) | 13 (34) | <.001 |

Notes: BUN = blood urea nitrogen; CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; CRP = C-reactive protein; ICU = intensive care unit; IL = interleukin; IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation; TNF = tumor necrosis factor.

*Candidates with severe brain injury were not included.

Figure 1.

Inclusion flowchart of study participants.

Diversity Metrics

Primary analyses—Swab-sample level

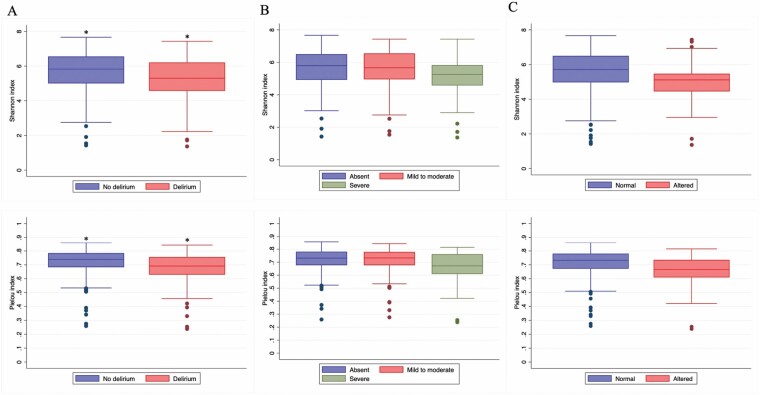

We analyzed 257 rectal swabs (Supplementary Figure 2). Overall, swabs from delirium participants had a lower diversity as measured by the Shannon and Pielou indexes (Figure 2). The results were confirmed in multivariable analyses, with higher alpha diversity metrics being associated with lower delirium occurrence (Shannon index: odds ratio [OR] = 0.77; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.60–0.99; p = .042); Pielou index: OR = 0.69; 95% CI = 0.51–0.87; p = .005). Additional results for alpha diversity are displayed in Supplementary Table 2.

Figure 2.

Alpha diversity by delirium-related outcomes in the overall swab sample. We represented Shannon and Pielou indexes of our primary analysis as follows: (A) Delirium occurrence; (B) Delirium severity by the Confusion Assessment Method-Severity (CAM-S); (C) Level of consciousness by the Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale (RASS). Data were analyzed using non-adjusted generalized estimating equations and presented as medians (interquartile ranges). Lower Shannon and Pielou indexes indicate poorer bacterial diversity and evenness. *p < .05.

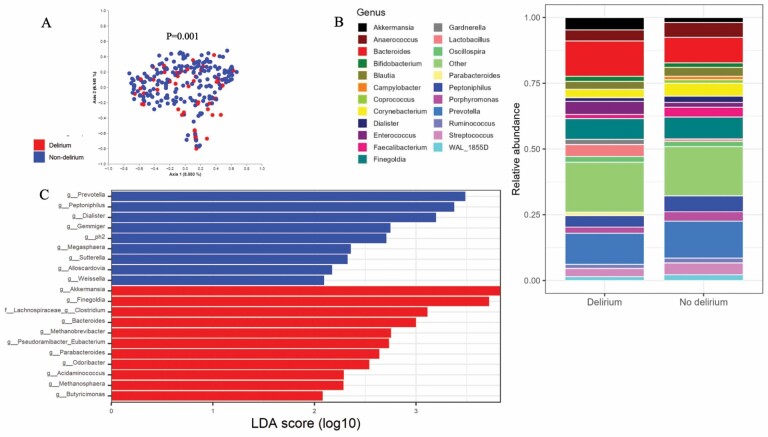

Our beta diversity analyses also revealed significant dissimilarities between the gut microbiota of delirium and non-delirium participants both for Bray-Curtis (Figure 3A) and unweighted UniFrac (p = .012). Likewise, PERMANOVA analyses demonstrated beta diversity differences in participants with impaired consciousness (Bray-Curtis: p = .006; unweighted UniFrac: p = .03), although no distinctions were detected according to delirium severity.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of beta diversity and relative abundances in the overall swab sample according to delirium occurrence. (A) Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) plot; each point in the graph represents a different sample. Blue dots represent swabs from non-delirium participants and red dots represent those from delirium participants. Beta diversity (Bray-Curtis distance) was numerically compared across groups using PERMANOVA. Results from the homogeneity of multivariable variances (PERMDISP) analyses showed that the observed differences were not alternatively explained by excessive data dispersion. (B) Relative abundances across groups at the genus level. (C) Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) for comparison of bacterial features across groups.

Secondary analyses—Participant level

Restricting our analyses to participants who were not delirious on admission (N = 114), we did not find differences in baseline diversity metrics between participants who never experienced delirium during hospital stay (N = 95) and those who had incident delirium (N = 19). However, after reincluding those 19 participants with delirium at admission (N = 133), we observed similar results to our primary analyses, with lower Shannon and Pielou indexes in the delirium group (Supplementary Table 1).

We found that higher baseline IL-6 and IL-10 were associated with lower median Shannon and Pielou indexes, whereas TNF-α was only associated with reduced Shannon index (Supplementary Table 2).

Microbial Composition and Core Microbiota

Overall, the most abundant taxa in our sample at the genus level were Bacteroides (5.7%), Prevotella (5%), Finegoldia (2.6%), Peptoniphilus (2.2%), Anaerococcus (1.7%), and Enterococcus (0.03%). Comparatively, we observed that the genera Lactobacillus and Peptoniphilus were less common in the delirium group, while Bacteroides and Enterococcus were more common (Figure 3B and Supplementary Figure 3).

We found independent associations between various bacterial taxa and delirium occurrence, impaired consciousness, and delirium severity (Supplementary Table 3). The genus Serratia was consistently associated with each of these outcomes, and the family Enterococcaceae was associated with impaired consciousness and higher delirium severity.

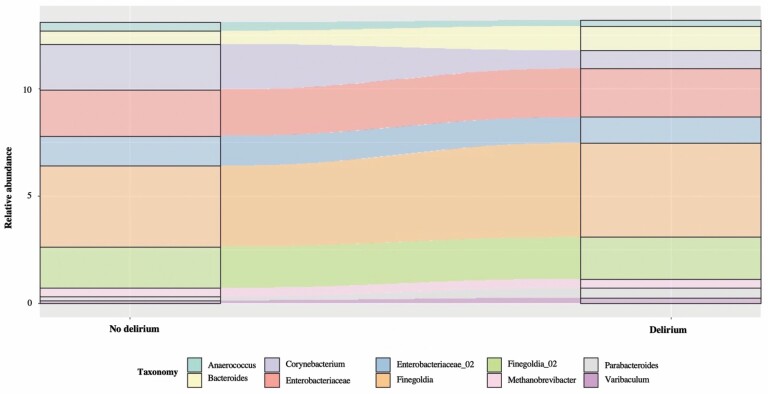

We identified bacteria from the genus Finelgodia as CORE 80% in our overall swab sample. The genera Bacteroides, Methanobrevibacter, and Varibaculum, were detected as CORE 80% in delirium episodes of participants with early CAM conversion, while the genus Parabacteroides was present in delirium episodes regardless of the CAM conversion time points (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 4.

Change in microbiota composition of swab samples from participants with early CAM conversion (incident delirium or delirium resolution). Samples were collected from the same individuals with and without delirium at different time points. For samples of participants with delirium, the core microbiota was uniquely represented by the genera Bacteroides, Parabacteroides, Methanobrevibacter, and Varibaculum. CAM, Confusion Assessment Method.

The differential abundance of specific bacterial taxa between the delirium and no delirium groups was further confirmed by the LEfSE analysis (Figure 3C).

We identified associations between altered baseline cytokines levels and relative abundances of delirium-related taxa (Supplementary Table 4). The genus Enterococcus was associated with higher levels of IL-6 (p = .045) and IL-10 (p < .0004) and a nonsignificant elevation of TNF-α levels (p = .13). Conversely, the genus Methanobrevibacter was enriched in samples of participants with lower cytokine levels, although this was only significant for IL-10 (p = .039).

Interaction Analysis: Nutritional Status and Antibiotic Use at Study Inclusion

Overall, we observed lower Shannon and Pielou indexes in samples from participants with worse nutritional status (Supplementary Figure 4). Alpha diversity was even more reduced in participants with delirium, regardless of their MNA category. Notably, those with both delirium and malnutrition had the lowest microbial diversity (p for interaction: Shannon = .054; Pielou = .039). Participants with delirium in the same nutritional stratum (ie, “At risk of malnutrition”) had similar abundances of specific taxa as observed in our principal analysis (Supplementary Figure 5). The relative abundances of these taxa were similar across the other nutritional categories, irrespective of delirium occurrence

We also identified a nonsignificant reduction in microbial diversity in samples of participants exposed to antibiotics for less than 24 hours of study inclusion. Antibiotics significantly modified the association between delirium and diversity indexes (p for interaction: Shannon = .048 and Pielou = .0006). Still, these indexes were consistently decreased in participants with delirium regardless of antibiotics, with the most significant reduction observed in those with delirium and antibiotic exposure (Supplementary Figure 6).

Discussion

Our results indicate that the gut microbiota differs in diversity and composition according to delirium occurrence, as demonstrated by alpha and beta diversity metrics, the relative abundance of taxa, and core microbiota. Participants who experienced delirium had lower richness and diversity of microorganisms and a distinctive representation of bacterial taxa. These results were also observed in participants with impaired consciousness, a more sensitive marker of acute mental change (30), supporting our main findings.

The association between gut microbiome composition and neuropsychiatric disorders has already been described in chronic disorders. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis reported that microbial richness was decreased in bipolar disorder, and beta diversity had consistent differences in depressive disorder, psychosis, and schizophrenia. These conditions also shared a transdiagnostic pattern with a decrease in anti-inflammatory butyrate-producing bacteria and an increase in pro-inflammatory bacteria (31). Conversely, acute neuropsychiatric disorders, such as delirium, have been less explored in the context of gut dysbiosis. We have found only one study reporting the presence of dysbiosis in an animal model of postoperative delirium (32). Analogous to our findings in older adults, mice with postoperative delirium had lower diversity measures and distinctive bacterial compositions in all taxonomic ranks. Older adults living with AD also demonstrate reduced diversity and microbial compositional differences compared to healthy controls. Similar to our results, the gut microbiota of AD patients appear to have a decreased Shannon index (33,34), and a marked enrichment of the family Enterobacteriaceae (33) and the genus Bacteroides (33,34). More than simply coincidental, those similar characteristics between the gut microbiota of AD and delirium patients might indicate a superimposition of shared mechanisms along the gut-brain axis that should be elucidated in the future.

Inflammation is a plausible mechanism linking delirium and gut dysbiosis since both conditions are associated with higher inflammatory biomarkers (11,35). Specific gut bacteria can produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, while other taxa (eg, Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium breve) often present anti-inflammatory activities (36). We detected increased IL-6 and IL-10 in participants with delirium and in those with lower alpha diversity indexes. The enrichment of Enterococcus was associated with higher levels of these cytokines, while Methanobrevibacter was associated with lower IL-10 levels. We also identified a marginal association between elevated TNF-α levels and decreased Shannon indexes, without compositional differences for delirium-related taxa. Although IL-10 is thought to be anti-inflammatory, there is evidence for a dual role of this cytokine, with a modulatory effect beginning early in acute phase responses, which explains the elevation of both IL-6 and IL-10 in our delirium group (37). The strong correlation between IL-6 and IL-10 has also been demonstrated in patients admitted to the intensive care unit (38). Despite these significant results, the secondary nature of our cytokine analyses might have attenuated the effect measures. Larger sample sizes or blood samples over different time points might help overcome our methodological constraints in future investigations. We also verified a predominance of the Enterobacteriaceae family after delirium incidence, particularly in samples from participants with early CAM conversion. Enterobacteriaceae is a pro-inflammatory taxon that modulates inflammatory responses and can exacerbate acute tissue damage (39). Altogether, these findings corroborate inflammation as a potential mediation pathway for the association between gut microbiome and delirium.

Other pathophysiological mechanisms possibly contribute to this relationship. Noteworthy, some bacterial strains can modulate the production of neurotransmitters involved in delirium occurrence (40,41). Bacteria from the genus Serratia, for example, can produce dopamine, while Bacteroides and Parabacteroides have been associated with GABA modulation (41,42). In our study, these genera were predominantly found in swab samples from the delirium group.

The influence of clinical factors related to delirium is also important to shed light on our findings. For instance, the genus Methanobrevibacter integrated the core microbiota only in participants with delirium. These methanogens are reported to appear in high concentrations in patients with firm stool consistency and slow intestinal transit, and constipation is recognized as a potential precipitating factor in delirium (43,44). Although our study was not designed to identify the temporality of Methanobrevibacter richness, constipation, and delirium, we can speculate that pathogenic bacteria may precede or accompany precipitant factors, increasing the risk of delirium. Future research should explore how different risk factors might interact with the gut microbiota composition and contribute to delirium occurrence. In this regard, we identified a significant interaction between nutritional status and delirium for some microbiota features. Patients with delirium and malnutrition had the lowest microbial diversity, although malnutrition itself did not modify the overall predominance of specific taxa associated with delirium. One should note that malnutrition is an important predisposing factor for delirium (45). In a cohort of 475 individuals aged 70 or older, the MNA categories “risk of malnutrition” and “overt malnutrition” were independently associated with postoperative delirium after adjusting for demographic, functional, and cognitive characteristics (46). Therefore, the co-occurrence of delirium and malnutrition might increase gut microbiota disturbances, potentially influencing clinical outcomes. In the context of our findings, this interface strengthens our understanding that targeted nutritional interventions should be explored in future studies as potential measures for delirium prevention and management.

Therefore, the association between delirium and gut microbiota is likely bidirectional. On the one hand, precipitating factors (eg, infections, metabolic disturbances) or those related to delirium pathophysiology (eg, inflammatory biomarkers, neuroendocrine dysregulation) are potential microbiota modifiers. On the other, gut bacteria might modulate the occurrence of delirium by producing (or failing to neutralize) cytokines and neurotransmitters. Even if causality is yet to be determined, our findings open new theoretical venues for delirium etiopathogenesis and treatment.

Some limitations of our investigation should be mentioned. First, we conducted a single-center study in a tertiary university hospital that preferably admits severely ill patients for specialized care. Second, we opted to use stricter eligibility criteria, which might have compromised our external validity. However, as a proof-of-concept study, our priority was to minimize confounding at the expense of the epidemiological representation of our target population. Moreover, we included a sizeable number of acutely ill older adults, with baseline characteristics comparable to previous studies (47). Finally, our microbiota analyses were focused on bacterial strains that have already been registered in validated databases, and specific functional pathways that might lead to delirium occurrence remain to be determined in these bacterial communities.

We also included patients using antibiotics for less than 24 hours at admission, knowing that older adults visiting the ED might have already started medications. Although antibiotics can potentially change the microbiota in a few hours, previous studies showed that their use for a median of 3 days did not significantly alter the gut microbiota of hospitalized older adults (48,49). Even so, we opted for a more conservative cutoff of 24 hours to minimize potential confounding.

Our study has many strengths. This was the first clinical study to investigate the association between gut microbiota and delirium in acutely ill older adults. We were able to implement a rigorous delirium detection protocol, and screening was completed twice daily by a trained research team. We collected an impressive number of rectal swab samples compared to the gut microbiota studies. In most cases, we collected more than one sample per participant at different time points, with minimal data loss. We not only analyzed baseline gut microbiota composition but also completed serial evaluations during hospital stay, capturing the conversion from non-delirious to delirious states and vice-versa. The prospective design enabled us to explore the association between gut microbiome and delirium bidirectionally over time. We also investigated whether malnutrition and antibiotics modified the association between delirium and gut microbiota. While our primary results were largely unchanged, the positive interactions suggest a more vulnerable microbiota in patients with delirium compared to their counterparts, susceptible to a greater impact in diversity when exposed to additional insults (eg, antibiotics). Finally, we were able to quantify inflammatory biomarkers in our sample and correlate them to delirium occurrence and microbiota diversity, exploring a potential mediation pathway in their association.

In conclusion, gut microbiota diversity and composition were significantly different according to delirium occurrence in a sample of acutely ill hospitalized older adults. The findings from this original proof-of-concept investigation should encourage future studies, such as those involving shotgun or metatranscriptomic analyses, to explore the potential role of bacterial metabolic pathways in the association between gut dysbiosis and delirium. Despite significant advances in the past decade, many gaps persist in understanding the pathophysiology and management of delirium (45). Our results provide groundwork for future experimental and clinical studies aiming to investigate new biomarkers and therapeutic targets across the brain-gut axis in delirium.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients, medical students, and laboratory researchers at the University of São Paulo, and statisticians at the Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, for their contribution to this study.

Contributor Information

Flavia Barreto Garcez, Laboratorio de Investigacao Medica em Envelhecimento (LIM 66), Servico de Geriatria, Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil; Departamento de Medicina, Hospital Universitario, Universidade Federal de Sergipe, São Cristóvão, Brazil.

Júlio César Garcia de Alencar, Laboratorio de Investigacao Medica em Emergencias Clinicas (LIM 51), Departamento de Clínica Médica, Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

Shirley Steffany Muñoz Fernandez, Departamento de Nutricao, Faculdade de Saude Publica, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

Vivian Iida Avelino-Silva, Departamento de Molestias Infecciosas e Parasitarias, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil; Faculdade Israelita de Ciencias da Saude Albert Einstein, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil.

Ester Cerdeira Sabino, Departamento de Molestias Infecciosas e Parasitarias, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil; Laboratório de Parasitologia Medica (LIM 46), Instituto de Medicina Tropical, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

Roberta Cristina Ruedas Martins, Laboratório de Parasitologia Medica (LIM 46), Instituto de Medicina Tropical, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

Lucas Augusto Moysés Franco, Laboratório de Parasitologia Medica (LIM 46), Instituto de Medicina Tropical, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

Sandra Maria Lima Ribeiro, Departamento de Nutricao, Faculdade de Saude Publica, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

Heraldo Possolo de Souza, Laboratorio de Investigacao Medica em Emergencias Clinicas (LIM 51), Departamento de Clínica Médica, Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

Thiago Junqueira Avelino-Silva, Laboratorio de Investigacao Medica em Envelhecimento (LIM 66), Servico de Geriatria, Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil; Faculdade Israelita de Ciencias da Saude Albert Einstein, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil.

Funding

This work was funded by the Network for Investigation of Delirium: Unifying Scientists (NIDUS) as a subaward of the National Institutes of Health Federal Award [grant numbers R24AG054259 and R33AG071744] for delirium and microbiome analyses and partially supported by Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), [grant number 2016/14566-4], for the analysis of inflammatory biomarkers. S.S.M.F. received a scholarship from the Coordenacao de Aperfeicoamento de Pessoal de Nivel Superior -Brazil (CAPES)-Financial Code 001.

Conflict of Interest

Vivian Iida Avelino-Silva is the University of São Paulo principal investigator for the Janssen COVID-19 vaccine trial and received fees for a lecture on COVID-19 vaccines from Bayer pharmaceuticals in 2020. The other authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1. Marchesi JR, Ravel J. The vocabulary of microbiome research: a proposal. Microbiome. 2015;3(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0094-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lynch SV, Pedersen O. The human intestinal microbiome in health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2369–2379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1600266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O’Toole PW, Jeffery IB. Gut microbiota and aging. Science (80-). 2015;350(6265):1214–1215. doi: 10.1126/science.aac8469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rogers GB, Keating DJ, Young RL, Wong ML, Licinio J, Wesselingh S. From gut dysbiosis to altered brain function and mental illness: mechanisms and pathways. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(6):738–748. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhuang Z-Q, Shen L-L, Li W-W, et al. Gut microbiota is altered in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63(4):1337–1346. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Borsom EM, Lee K, Cope EK. Do the bugs in your gut eat your memories? Relationship between gut microbiota and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Sci. 2020;10(11):814. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10110814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhuang Z, Yang R, Wang W, Qi L, Huang T. Associations between gut microbiota and Alzheimer’s disease, major depressive disorder, and schizophrenia. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-01961-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zheng P, Zeng B, Zhou C, et al. Gut microbiome remodeling induces depressive-like behaviors through a pathway mediated by the host’s metabolism. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(6):786–796. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marcantonio ER. Delirium in hospitalized older adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(15):1456–1466. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1605501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Inouye SK, Westendorp RG, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911–922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60688-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. DeJong EN, Surette MG, Bowdish DME. The gut microbiota and unhealthy aging: disentangling cause from consequence. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;28(2):180–189. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grenham S, Clarke G, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Brain-gut-microbe communication in health and disease. Front Physiol. 2011;2 DEC(December):1–15. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Foster JA, Rinaman L, Cryan JF. Stress & the gut-brain axis: regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiol Stress. 2017;7:124–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maldonado JR. Neuropathogenesis of delirium: review of current etiologic theories and common pathways. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(12):1190–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ojima M, Motooka D, Shimizu K, et al. Metagenomic analysis reveals dynamic changes of whole gut microbiota in the acute phase of intensive care unit patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(6):1628–1634. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-4011-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guigoz Y. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA (R)) review of the literature - What does it tell us? J Nutr Heal Aging. 2006;10:466–487. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(98)00171-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Apolinario D, Lichtenthaler DG, Magaldi RM, et al. Using temporal orientation, category fluency, and word recall for detecting cognitive impairment: the 10-point cognitive screener (10-CS). Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(1):4–12. doi: 10.1002/gps.4282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. COPAN Diagnostics. ESwab(TM) - Package insert and How to use guide. Accessed October 4, 2020. https://www.copanusa.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ESwab-Package-Insert_HPC030_eSwab_copoliestere_Rev00_Date2016.02.pdf

- 21. Bassis CM, Moore NM, Lolans K, et al. ; CDC Prevention Epicenters Program. Comparison of stool versus rectal swab samples and storage conditions on bacterial community profiles. BMC Microbiol. 2017;17(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s12866-017-0983-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Inouye SK, Van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method: a new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941–948. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tieges Z, Brown LJE, MacLullich AMJ. Objective assessment of attention in delirium: a narrative review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29(12):1185–1197. doi: 10.1002/gps.4131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(10):1338–1344. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Inouye SK, Kosar CM, Tommet D, et al. The CAM-S: Development and validation of a new scoring system for delirium severity in 2 cohorts. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(8):526–533. doi: 10.7326/M13-1927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Knight R, Vrbanac A, Taylor BC, et al. Best practices for analysing microbiomes. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(7):410–422. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0029-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12(6):R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Knol MJ, VanderWeele TJ. Recommendations for presenting analyses of effect modification and interaction. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(2):514–520. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shrier I, Platt RW. Reducing bias through directed acyclic graphs. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Garcez FB, Jacob-Filho W, Avelino-Silva TJ. Association between level of arousal and 30-day survival in acutely ill older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(4):493–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nikolova VL, Smith MRB, Hall LJ, Cleare AJ, Stone JM, Young AH. Perturbations in gut microbiota composition in psychiatric disorders: a review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(12):1343–1354. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang J, Bi J, Guo G, et al. Abnormal composition of gut microbiota contributes to delirium-like behaviors after abdominal surgery in mice. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2019;25(6):685–696. doi: 10.1111/cns.13103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu P, Wu L, Peng G, et al. Altered microbiomes distinguish Alzheimer’s disease from amnestic mild cognitive impairment and health in a Chinese cohort. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;80:633–643. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vogt NM, Kerby RL, Dill-McFarland KA, et al. Gut microbiome alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):13537. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13601-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McNeil JB, Hughes CG, Girard T, et al. Plasma biomarkers of inflammation, coagulation, and brain injury as predictors of delirium duration in older hospitalized patients. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e02264126–e02264115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thevaranjan N, Puchta A, Schulz C, et al. Age-associated microbial dysbiosis promotes intestinal permeability, systemic inflammation, and macrophage dysfunction. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21(4):455–466.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Saraiva M, Vieira P, O’Garra A. Biology and therapeutic potential of interleukin-10. J Exp Med. 2020;217(1): e20190418. doi: 10.1084/jem.20190418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ritter C, Tomasi CD, Dal-Pizzol F, et al. Inflammation biomarkers and delirium in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2014;18(3):R106. doi: 10.1186/cc13887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Menezes-Garcia Z, Do Nascimento Arifa RD, Acúrcio L, et al. Colonization by Enterobacteriaceae is crucial for acute inflammatory responses in murine small intestine via regulation of corticosterone production. Gut Microbes. 2020;11(6):1531–1546. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2020.1765946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fond G, Boukouaci W, Chevalier G, et al. The “psychomicrobiotic”: Targeting microbiota in major psychiatric disorders: a systematic review. Pathol Biol. 2015;63(1):35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lyte M. Probiotics function mechanistically as delivery vehicles for neuroactive compounds: microbial endocrinology in the design and use of probiotics. Bioessays. 2011;33(8):574–581. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Strandwitz P, Kim KH, Terekhova D, et al. GABA-modulating bacteria of the human gut microbiota. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4(3):396–403. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0307-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vandeputte D, Falony G, Vieira-Silva S, Tito RY, Joossens M, Raes J. Stool consistency is strongly associated with gut microbiota richness and composition, enterotypes and bacterial growth rates. Gut. 2016;65(1):57–62. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Smonig R, Wallenhorst T, Bouju P, et al. Constipation is independently associated with delirium in critically ill ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(1):126–127. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-4050-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wilson JE, Mart MF, Cunningham C, et al. Delirium. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2020;6(1):90. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00223-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mazzola P, Ward L, Zazzetta S, et al. Association between preoperative malnutrition and postoperative delirium after hip fracture surgery in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(6):1222–1228. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bo M, Bonetto M, Bottignole G, et al. Postdischarge clinical outcomes in older medical patients with an emergency department stay-associated delirium onset. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(9):e18–e19. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Milani C, Ticinesi A, Gerritsen J, et al. Gut microbiota composition and Clostridium difficile infection in hospitalized elderly individuals: a metagenomic study. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):25945. doi: 10.1038/srep25945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ticinesi A, Milani C, Lauretani F, et al. Gut microbiota composition is associated with polypharmacy in elderly hospitalized patients. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):11102. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10734-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.