To the Editor:

Monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL), monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), and clonal hematopoiesis (CH) are all asymptomatic hematological conditions characterized by clonal expansion of blood cells [1, 2]. These conditions are notably associated with increased risk of hematologic cancers. Each condition has an annual progression rate of ~1–2%/year, with MBL progressing to chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) [3] or lymphoid malignancies [4], MGUS progressing mostly to multiple myeloma (MM) [5], and CH progressing predominately to myeloid neoplasms [2]. Additionally, these premalignant conditions (or a particular subtype of them) are associated with adverse outcomes, including increased risk of infections [6–8] and reduced overall survival [2, 4, 5]. Known risk factors for these conditions are limited but include aging [4, 9] and common inherited variants [10–12].

The prevalence of each of these conditions has been established, ranging from 5–25% overall, with particular subtypes having varying prevalence rates [2, 4, 9]. However, little is known about their co-occurrence. One hospital-based cohort of ~1500 non-hematological patients screened for MBL and MGUS found no significant association between them [13]. Another study of 777 subjects enrolled in the Monzino 80-plus cohort found no significant association between MGUS and CH [14]. Herein, we investigate the co-occurrence of MBL with MGUS and with CH, along with the associations between them and the prevalence of all three conditions.

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center, and participants provided written informed consent. Study participants were a cross-sectional sample from the Mayo Clinic Biobank who were recruited between 2009–2016 from general medical practice clinics, randomly selected from participants who had no prior history of hematological cancers, 40 years or older, and provided a biospecimen needed for MBL and MGUS screening [4]. For a more representative cohort, we included participants who resided predominantly from counties surrounding Mayo Clinic and therefore who typically receive their general medical care at Mayo Clinic. CH screening was conducted on a subset of these individuals and were selected based on MBL status (a case-control study comprised of 330 individuals with MBL and 588 age- and sex-matched individuals without MBL).

The methods used for MBL screening [4, 7] and MGUS screening [9] have been previously published. For CH, peripheral blood DNA was used to sequence the coding regions from 42 CH-related genes (Supplementary Table 1) using the Illumina HiSeq 4000. The average coverage depth was >1000x. Somatic mutations were called using MuTect2. Variants were excluded if the number of reads supporting variant alleles was <8, variant allele fraction (VAF) was <0.01, gnomAD allele frequency was ≥0.005, more than 80% of the variant reads came from a single strand, or the VAF did not deviate from 50% at a p value of at least 0.00001 unless reported in COSMIC at least 10 times. Loss-of-function variants (nonsense, frameshift, and consensus splice sites) and missense variants, classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic, were used to identify individuals with CH. Different laboratory technicians performed each premalignant screening assay, thus were blinded to the results of the other screening assays.

Logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) using R (version 3.6.2). All analyses were adjusted for age and sex; in addition, association analyses between CH and MGUS were also adjusted for MBL status.

Results/Discussion

In total, 1630 individuals were screened for MBL and MGUS; 1151 (70.6%) were negative for both, 275 (16.9%) identified to have MBL only, 147 (9.0%) identified to have MGUS only, and 57 (3.5%) identified to have both MBL and MGUS (Table 1). Individuals with MBL only were, on average, older than those without MBL/MGUS (median 70 vs. 63 years of age, respectively, p < 0.001) and were more likely to be male (54.5% vs. 41.0%, respectively, p < 0.001). CLL-like MBL was the most common MBL subtype (87.3%), followed by non-CLL-like (8.4%), and atypical MBL (4.4%). Individuals with MGUS only were also older than those without MBL/MGUS (median 68 vs. 63 years of age, respectively, p < 0.001); however, there was no significant difference in sex (p = 0.13). Non-IgM (86.0%), and particularly IgG MGUS (63.5%), were the most common MGUS isotypes.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by premalignant condition status.

| No MBL/MGUS (N = 1151) | MBL only (N = 275) | MGUS only (N = 147) | Both MBL/MGUS (N = 57) | Total (N = 1630) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 679 (59.0%) | 125 (45.5%) | 77 (52.4%) | 29 (50.9%) | 910 (55.8%) |

| Male | 472 (41.0%) | 150 (54.5%) | 70 (47.6%) | 28 (49.1%) | 720 (44.2%) |

| Age at MBL screening (years) | |||||

| Median | 63.0 | 70.0 | 68.0 | 72.0 | 65.0 |

| Range | 40.0–89.0 | 43.0–96.0 | 43.0–94.0 | 53.0–94.0 | 40.0–96.0 |

| MBL immunophenotype | |||||

| Atypical | – | 12 (4.4%) | – | 5 (8.8%) | 17 (5.1%) |

| CLL-like | – | 240 (87.3%) | – | 42 (73.7%) | 282 (84.9%) |

| Non-CLL-like | – | 23 (8.4%) | – | 10 (17.5%) | 33 (9.9%) |

| MBL clonal size | |||||

| HC-MBL | – | 15 (5.5%) | – | 7 (12.3%) | 22 (6.6%) |

| LC-MBL | – | 260 (94.5%) | – | 50 (87.7%) | 310 (93.4%) |

| MGUS heavy chain isotype | |||||

| Missing | – | – | 1 | 0 | 1427 |

| Biclonal | – | – | 8 (5.5%) | 6 (10.5%) | 14 (6.9%) |

| IgA | – | – | 21 (14.4%) | 10 (17.5%) | 31 (15.3%) |

| IgG | – | – | 96 (65.8%) | 33 (57.9%) | 129 (63.5%) |

| IgM | – | – | 21 (14.4%) | 8 (14.0%) | 29 (14.3%) |

| M-Spike (g/dl) | |||||

| Missing | – | – | 13 | – | – |

| <0.2 | – | – | 103 (75.2%) | 41 (74.5%) | 144 (75.0%) |

| 0.2–1.5 | – | – | 29 (21.2%) | 13 (23.6%) | 42 (21.9%) |

| ≥1.5 | – | – | 5 (3.6%) | 1 (1.8%) | 6 (3.1%) |

| CH (overall)a | |||||

| Missing | 644 | 2 | 66 | 0 | 712 |

| No | 369 (72.8%) | 198 (72.5%) | 62 (76.5%) | 40 (70.2%) | 669 (72.9%) |

| Yes | 138 (27.2%) | 75 (27.5%) | 19 (23.5%) | 17 (29.8%) | 249 (27.1%) |

| DNMT3A CH | 63 (12.4%) | 37 (13.6%) | 5 (6.2%) | 4 (7.0%) | 109 (11.9%) |

| TET2 CH | 45 (8.9%) | 18 (6.6%) | 10 (12.3%) | 4 (7.0%) | 77 (8.4%) |

| ASXL1 CH | 10 (2.0%) | 4 (1.5%) | 1 (1.2%) | 3 (5.3%) | 18 (2.0%) |

| nonDTA CH | 41 (8.1%) | 28 (10.3%) | 8 (9.9%) | 10 (17.5%) | 87 (9.5%) |

MBL monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis, MGUS monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, CH clonal hematopoiesis, LC-MBL low-count MBL, HC-MBL high-count MBL, nonDTA non DNMT3A, TET2, or ASXL1 somatic mutation carrier.

aFrequencies exclude individuals missing CH sequencing information.

Among the 57 individuals with both MGUS and MBL, 49.1% were male and median age was 72 years (Table 1). The frequency of MBL and MGUS coexisting was 3.5%, which is higher than the 0.4% reported previously [13]. This discrepancy is likely due to the higher sensitivity of MGUS detection used in the current study [15]. When restricted to the detection metrics of M-spike >0.2 g/dl, the frequency of those with MBL and MGUS was similar to the prior report (0.8%), although the prior publication was unclear of their M-spike threshold.

A subset of 918 individuals were sequenced for CH, of whom 249 (27.1%) had CH detected. Genes DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1 (DTA-CH) made up 65.1% of the CH carriers (Table 1).

Although CH screening was not available on the entire cohort, it was complete for those with both MBL and MGUS (Table 1), allowing for accurate estimates of all three conditions. In total, 17 (1.0%) individuals concurrently had all three premalignant conditions. These individuals were 47% male with a median age of 78 years. CLL-like MBL was the most common MBL subtype (47.1%) and non-IgM MGUS were the most common MGUS isotypes (73.7%).

Further, CH screening was available on all but 2 individuals with MBL from the full cohort, allowing for accurate estimate of the prevalence of CH and MBL. In total, 92 (5.6%) out of the1,630 individuals concurrently had MBL and CH. We did not have sequencing completed on all MGUS in the full sample and thus were unable to estimate their co-occurrence.

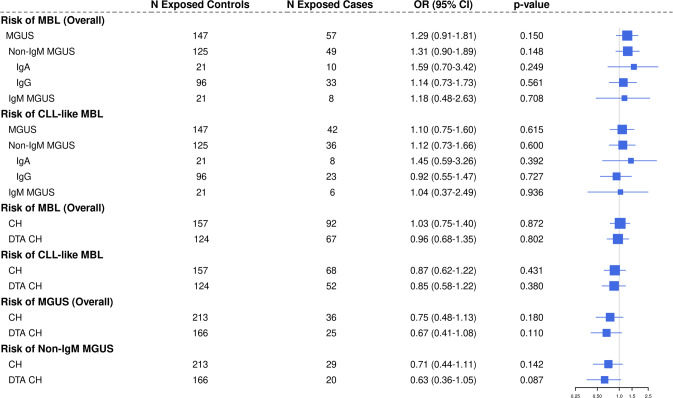

The associations among these premalignant conditions are shown in Fig. 1. There was an elevated OR for the association of MGUS overall with MBL (OR = 1.29, 95% CI: 0.91–1.81, p = 0.15) which did not reach statistical significance. The OR was highest for IgA MGUS 1.59 (95% CI: 0.70–3.42), but small sample sizes limited power for subtype specific associations.

Fig. 1. Forest plot of associations between premalignant conditions of monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL), monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), and clonal hematopoiesis (CH).

DTA CH: DNMT3A, TET2, or ASXL1 somatic mutation carrier.

When we subset to individuals with CLL-like MBL, there was no evidence of an association between MGUS overall and CLL-like MBL (OR = 1.10, 95% CI: 0.75–1.60, p = 0.62, Fig. 1). Similarly, there was no evidence of an association between CLL-like MBL and non-IgM MGUS or any of the MGUS isotypes, although power was limited for these MGUS isotype analyses. Moreover, there was no statistical evidence of an association between CH and MBL overall or with CLL-like MBL (ORs 1.03 and 0.87, respectively). There was also no evidence of an association between DTA-CH and MBL overall or CLL-like MBL (ORs 0.96 and 0.85, respectively). When investigating the relationship between CH and MGUS, we found no statistical evidence of an association, although there may be an inverse relationship between CH and MGUS (Fig. 1), like the nonsignificant association in Da Via et al. [14]. The results were similar when analysis was limited to individuals with CH who had a VAF > 2% (Supplementary Table 2) [2].

Lastly, there are 19 genes in our CH gene list (Supplementary Table 1) that are also recurrently mutated in lymphoid malignancies. Because MBL and MGUS are precursors to lymphoid malignancies, we restricted our CH definition to exclude these 19 genes and found similar results to our overall analysis (Supplementary Table 2).

In summary, this study of 1630 individuals found no statistical evidence of a relationship among risk of common hematological premalignant conditions. Particularly, we found no evidence of associations between MGUS with CLL-like MBL or between CH with CLL-like MBL. However, further studies are needed to evaluate associations among the rare subtype conditions due to limited sample size herein. Overall, these results suggest these premalignant conditions do not appear to cluster together. Future studies are needed to investigate whether those with two or more of these conditions have increased clinical phenotypes (e.g., cytopenias, cancers, infections) or mortality compared to those with only one or no premalignant condition.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01 AG58266, R01 CA235026, and U01 CA271014. The Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine provided the Mayo Clinic Biobank materials.

Author contributions

Concept and study design was performed by: SLS, TDS, CMV, and NJB. Manuscript was drafted by NJB, CMV, and SLS. Interpretation of data and manuscript reviewed was done by all authors.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Celine M. Vachon, Susan L. Slager.

Contributor Information

Celine M. Vachon, Email: Vachon.Celine@mayo.edu

Susan L. Slager, Email: Slager.Susan@mayo.edu

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41375-023-01914-z.

References

- 1.Alaggio R, Amador C, Anagnostopoulos I, Attygalle AD, Araujo IBO, Berti E, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of haematolymphoid tumours: lymphoid neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36:1720–48. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01620-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niroula A, Sekar A, Murakami MA, Trinder M, Agrawal M, Wong WJ, et al. Distinction of lymphoid and myeloid clonal hematopoiesis. Nat Med. 2021;27:1921–7. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slager SL, Lanasa MC, Marti GE, Achenbach SJ, Camp NJ, Abbasi F, et al. Natural history of monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis among relatives in CLL families. Blood. 2021;137:2046–56. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slager SL, Parikh SA, Achenbach SJ, Norman AD, Rabe KG, Boddicker NJ, et al. Progression and survival of monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL): a screening study of 10,139 individuals. Blood. 2022;140:1702–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022016279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, Offord JR, Larson DR, Plevak MF, et al. A long-term study of prognosis in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:564–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa01133202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kristinsson SY, Tang M, Pfeiffer RM, Bjorkholm M, Goldin LR, Blimark C, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and risk of infections: a population-based study. Haematologica. 2012;97:854–8. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.054015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shanafelt TD, Kay NE, Parikh SA, Achenbach SJ, Lesnick CE, Hanson CA, et al. Risk of serious infection among individuals with and without low count monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL) Leukemia. 2021;35:239–44. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0799-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zekavat SM, Lin SH, Bick AG, Liu A, Paruchuri K, Wang C, et al. Hematopoietic mosaic chromosomal alterations increase the risk for diverse types of infection. Nat Med. 2021;27:1012–24. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01371-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vachon CM, Murray J, Allmer C, Larson D, Norman AD, Sinnwell JP, et al. Prevalence of heavy chain MGUS by race and family history risk groups using a high-sensitivity screening method. Blood Adv. 2022;6:3746–50. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021006201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bick AG, Weinstock JS, Nandakumar SK, Fulco CP, Bao EL, Zekavat SM, et al. Inherited causes of clonal haematopoiesis in 97,691 whole genomes. Nature. 2020;586:763–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clay-Gilmour AI, Hildebrandt MAT, Brown EE, Hofmann JN, Spinelli JJ, Giles GG, et al. Coinherited genetics of multiple myeloma and its precursor, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood Adv. 2020;4:2789–97. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleinstern G, Weinberg JB, Parikh SA, Braggio E, Achenbach SJ, Robinson DP, et al. Polygenic risk score and risk of monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis in caucasians and risk of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in African Americans. Leukemia. 2022;36:119–25. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01344-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voigtlaender M, Vogler B, Trepel M, Panse J, Jung R, Bokemeyer C, et al. Hospital population screening reveals overrepresentation of CD5(-) monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance of IgM type. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:1559–65. doi: 10.1007/s00277-015-2409-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Da Via MC, Lionetti M, Marella A, Matera A, Travaglino E, Signaroldi E, et al. MGUS and clonal hematopoiesis show unrelated clinical and biological trajectories in an older population cohort. Blood Adv. 2022;6:5702–6. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021006498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray D, Kumar SK, Kyle RA, Dispenzieri A, Dasari S, Larson DR, et al. Detection and prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a study utilizing mass spectrometry-based monoclonal immunoglobulin rapid accurate mass measurement. Blood Cancer J. 2019;9:102. doi: 10.1038/s41408-019-0263-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.