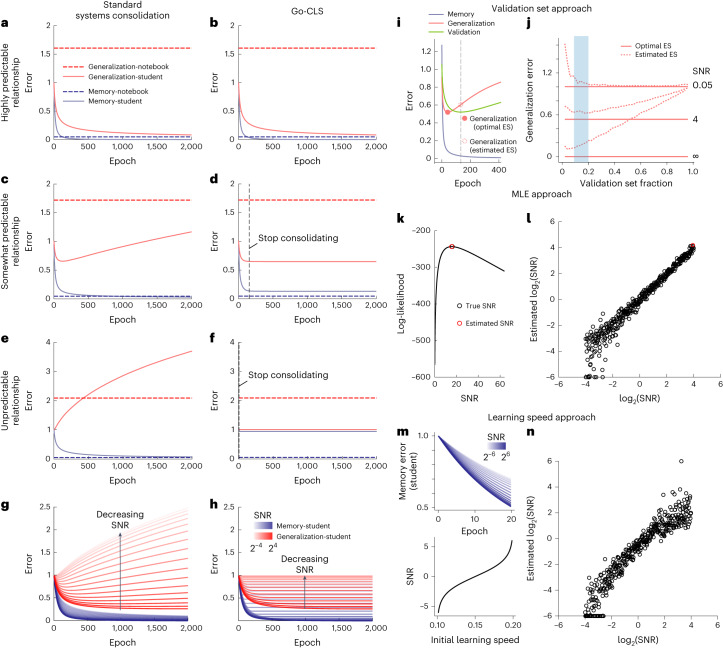

Fig. 2. The predictability of experience controls the dynamics of systems consolidation.

a–h, Dynamics of student generalization error, student memorization error, notebook generalization error and notebook memorization error when optimizing for student memorization (a, c, e and g) or generalization (b, d, f and h) performance. The student’s input dimension is N = 100, and the number of patterns stored in the notebook is P = 100 (all encoded at epoch = 1; epochs in the x axis correspond to time passage during systems consolidation). The notebook contains M = 2,000 units, with a sparsity a = 0.05. During each epoch, 100 patterns are randomly sampled from the P stored patterns for reactivating and training the student. The student’s learning rate is 0.015. Teachers differed in their levels of predictability (a and b, SNR = ∞; c and d, SNR = 4; e and f, SNR = 0.05; g and h, SNR ranges from 2−4 to 24). i–n, Methods for regulating consolidation. i, Using a validation set to estimate optimal early stopping time (SNR = 4, P = N = 100, 10% of P are used as validation set and not used for training). Filled red dot marks the generalization error at the optimal early stopping time (optimal ES), and dashed red dot marks the generalization error at the early stopping time estimated by the validation set (estimated ES). The vertical gray dashed line marks the estimated early stopping time. j, Generalization errors at optimal (solid red lines) vs estimated early stopping time (dashed red lines), as a function of the validation set fraction, SNR and α (P/N). The blue shading indicates the validation set fraction from 10% to 20%. k, Illustration of maximum likelihood estimation (MLE; Supplementary Information Section 9.2). l, MLE predicts SNR well from teacher-generated data. m, Initial learning speed monotonically increases as a function of SNR. n, Initial learning speed serves as a good feature for estimating true SNR in numerical simulations (P = N = 1,000).