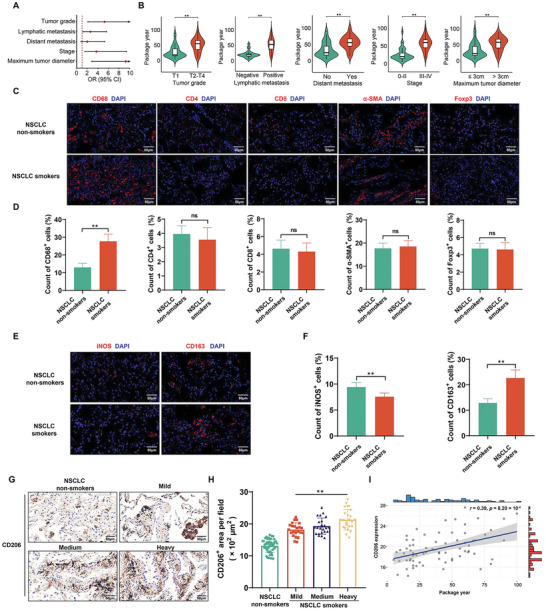

Figure 1.

Cigarette smoking is associated with the progression of NSCLC and the accumulation of M2‐TAMs in NSCLC tissues. A) Logistic regression models of associations of cigarette smoking with tumor grade, lymphatic metastasis, distant metastasis, stage, and maximum tumor diameter for individuals with NSCLC. The logistic regression models were adjusted for age and sex (Non‐smokers, n = 48; Smokers, n = 70). B) Levels of cigarette smoking for individuals with NSCLC with different tumor grades, lymphatic metastasis, distant metastasis, stage, and maximum tumor diameter (n = 70). C) Immunofluorescence staining for macrophages (CD68+), CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CAFs (α‐SMA+), and Tregs (Foxp3+) was measured to reveal different cell types (red) in the tumor microenvironment (n = 8), and D) measurement of CD68, CD4, CD8, α‐SMA, and Foxp3‐positive cells in NSCLC tissues from smoking or never‐smoking patients (n = 8, randomly selected fields per group). DAPI labels nuclei (blue). Scale bar, 50 µm. E) Immunofluorescence staining for iNOS (red) and CD163 (red) was measured (n = 8), and F) measurement of iNOS‐and CD163‐positive cells in NSCLC tissues from smoking or never‐smoking patients (n = 8, randomly selected fields per group). DAPI labels nuclei (blue). Scale bar, 50 µm. NSCLC patients with a smoking history were divided into groups according to levels of cigarette smoking (Non‐smokers, n = 48; Mild group, n = 23; Medium group, n = 23; Heavy group, n = 24). G) IHC staining for CD206 was conducted, and H) measurement of CD206‐positive signals in NSCLC tissues from different levels of cigarette smoking. Scale bar, 50 µm. I) Correlation of CD206 expression in NSCLC tissues for NSCLC patients with different levels of cigarette smoking. All data represent means ± SD. ns, not significant. *p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.