Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus poses a severe public health problem as one of the vital causative agents of healthcare- and community-acquired infections. There is a globally urgent need for new drugs with a novel mode of action (MoA) to combat S. aureus biofilms and persisters that tolerate antibiotic treatment. We demonstrate that a benzonaphthopyranone glycoside, chrysomycin A (ChryA), is a rapid bactericide that is highly active against S. aureus persisters, robustly eradicates biofilms in vitro, and shows a sustainable killing efficacy in vivo. ChryA was suggested to target multiple critical cellular processes. A wide range of genetic and biochemical approaches showed that ChryA directly binds to GlmU and DapD, involved in the biosynthetic pathways for the cell wall peptidoglycan and lysine precursors, respectively, and inhibits the acetyltransferase activities by competition with their mutual substrate acetyl-CoA. Our study provides an effective antimicrobial strategy combining multiple MoAs onto a single small molecule for treatments of S. aureus persistent infections.

Chrysomycin A utilizes multiple mechanisms to fight against Staphylococcus aureus persistent infection.

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is a major causative agent of nosocomial infections, which causes a broad spectrum of diseases ranging from minor skin infections to life-threatening diseases, such as endocarditis, osteomyelitis, and sepsis (1, 2). Over the past several decades, infection with S. aureus has become increasingly challenging to treat because of the emergence and rapid spread of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (3). More seriously, some MRSA strains resistant to vancomycin, linezolid, and daptomycin, three antibiotics of last resort for S. aureus infections, have also recently been isolated from the clinical setting (4–6). Although these antibiotics target cell wall biosynthesis, membrane integrity, or protein biosynthesis, they have already been countered via different resistance mechanisms (7). Moreover, substantially contributing to the problematic treatment of S. aureus infections is the presence of a small fraction of persister cells that are either completely dormant or have selectively inactivated processes that are typically targeted by antibiotics (8). Adding to the challenge is the ability of S. aureus to form biofilms on biotic and abiotic surfaces, which results in failures of antibiotic treatment (9, 10). Therefore, new antibacterial agents with mechanisms of action different from clinically available antibiotics are urgently needed to address the global threat of MRSA infections.

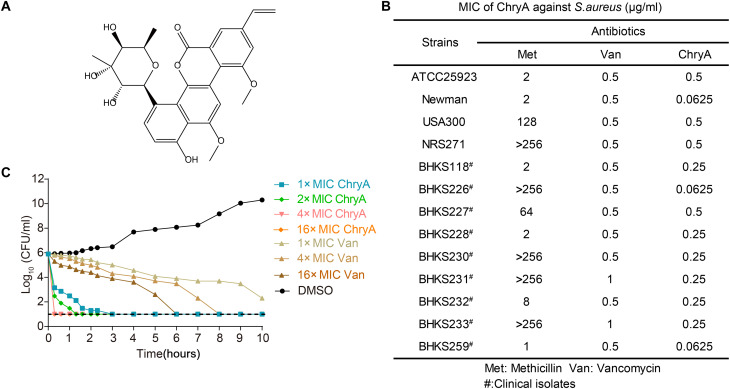

One of the most promising strategies for developing novel antibiotics is to tap into natural product sources (11). There have been some recent discoveries based on natural products, such as acyldepsipeptides (12, 13), teixobactin (14), and complestatin and corbomycin (15) that exhibit potent antibacterial activities against S. aureus. Some natural products like artocarpin (AH-5) (16), cudraflavone C (17), 4,6-dibromo-2-(2′, 4′-dibromo phenoxy)phenol, and 3,4,6-tribromo-2-(2′,4′-dibromophenoxy)phenol (18) also displayed profound antibiofilm and killing activity against S. aureus persisters. Chrysomycin A (ChryA) is a benzonaphthopyranone glycoside that was first isolated from Streptomyces spp. in 1955 (Fig. 1A) (19). ChryA belongs to the gilvocarcin family of C-aryl glycoside natural products (20) and shows various biological activities, including antibacteriophage (19), antibacterial (21–24), antitumor (25, 26), and antineuroinflammatory activities (27), implying its considerable potential as a multiple-target agent. Analogous compounds of ChryA, such as gilvocarcins, ravidomycins, and polycarcins, are also known as antibacterial and antitumor chemicals (21, 28). Although ChryA and its analog gilvocarcin V were verified as DNA-intercalating agents that can initiate DNA damage (21), the precise mode of antibacterial action remains unknown for a long time.

Fig. 1. Antibacterial properties of ChryA.

(A) Chemical structure of ChryA. (B) Antibacterial activity of ChryA against S. aureus standard strains and clinical isolates. (C) The time-dependent killing of S. aureus Newman by ChryA and vancomycin (Van). An exponential culture of S. aureus was challenged with various concentrations of antibiotics. Data are representative of three independent experiments. CFU, colony-forming units.

Here, we present our findings that ChryA is a potent bactericidal agent that kills S. aureus persister cells and exhibits unprecedented antibiofilm activity of MRSA. Whole-genome sequencing of spontaneous ChryA-resistant mutants identified six genes as potential targets, two of which are GlmU and DapD relating to cell wall peptidoglycan and lysine precursor biosynthesis, respectively. We also showed that ChryA acts as a competitive inhibitor of GlmU and DapD with respect to their mutual substrate acetyl-CoA (coenzyme A). Such multitarget mode of action (MoA) of ChryA endows its extraordinarily antibacterial efficacy in a mouse epicutaneous model of MRSA infection. Our study first elucidated the complex MoA of the natural product ChryA and characterized a promising drug lead for the development of anti–S. aureus drugs.

RESULTS

ChryA rapidly eradicates S. aureus persister and has significant antibiofilm activity

In line with previous findings, ChryA had potent antimicrobial activities against Gram-positive pathogens but was not generally effective against Gram-negative bacteria (table S1). Our study showed that the antibacterial activity of ChryA [minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) ranging from 0.0625 to 0.5 μg/ml] against S. aureus standard strains and clinical MRSA isolates is more potent than the conventional antibiotic vancomycin (MIC of 0.5 to 1 μg/ml; Fig. 1B). The killing kinetics study demonstrated that ChryA had a concentration-dependent bactericidal activity with a rapid killing effect. A 2.7-log reduction in colony-forming units (CFU) and complete killing were observed when exposed to ChryA at 1× MIC (0.0625 μg/ml) and at 4× to 16× MIC within 20 min, respectively (Fig. 1C). Note that as a control experiment, vancomycin exhibited much slower killing against S. aureus Newman than ChryA.

Treatment of S. aureus infections is hampered by its ability to enter into a nongrowing and dormant state, referred to as persisters (8, 29). S. aureus cells in the stationary phase behave as persisters and are extremely difficult to kill with antibiotics (30). Here, ChryA at 2× MIC showed excellent killing, with complete eradication of stationary cells to the limit of detection (Fig. 2A). The antipersister activity of ChryA was also evaluated on the basis of its competence in eliminating persister cells formed in antibiotic-pretreated S. aureus cultures. ChryA at 2× MIC also completely killed persisters induced by ciprofloxacin (Fig. 2B) or penicillin G within 20 min (Fig. 2C). In contrast, S. aureus persisters demonstrated a high level of tolerance to 100× or 10× MIC of ciprofloxacin and penicillin G.

Fig. 2. ChryA kills persisters and exhibits antibiofilm activity.

(A) ChryA kills stationary phase S. aureus Newman cells. Bacterial cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and treated with the indicated concentrations of ChryA, ciprofloxacin (Cipro; MIC = 0.5 μg/ml), penicillin G (Pen; MIC = 0.125 μg/ml), or DMSO for 12 hours. (B and C) ChryA kills persisters surviving ciprofloxacin or penicillin treatment. S. aureus Newman cells were incubated with 10× MIC of ciprofloxacin (B) or penicillin G (C) for 6 hours to isolate survival persister cells. Cells were then harvested, resuspended in PBS, and treated with ChryA (2× MIC) and penicillin G (10× MIC) (B) or ciprofloxacin (10× MIC) (C) for 3 hours. (D) ChryA inhibits biofilm formation of S. aureus MRSA strain, USA300. The data are normalized to DMSO (100% biofilm). (E) Eradication of MRSA USA300 preformed biofilm was determined by the crystal violet staining method. (F and G) Antibiofilm activity of ChryA against MRSA USA300 was determined by the viable colony count method (F) and SYTO9-PI double staining using the LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit (G). All experiments were performed as three biologically independent experiments, and the mean ± SD is shown. Dashed lines indicate the limit of detection (10 CFU/ml). Statistical differences between control (DMSO) and antibiotic treatment groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (****P < 0.0001; ns, no significant difference).

The ability to form a biofilm is a key virulence determinant for S. aureus infection and colonization (31). We first used crystal violet assays to evaluate the antibiofilm ability of ChryA. ChryA was found to inhibit biofilm formation and disrupt mature biofilms of S. aureus in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2, D, and E). ChryA at sub-MIC level (0.25 μg/ml, 0.5× MIC) reduced the biofilm biomass of S. aureus USA300 by 58%. ChryA also eradicated 55, 88, and 95% of S. aureus mature biofilms at 0.5×, 2×, and 8× MIC after 24 hours of treatment, respectively. Similar antibiofilm results were observed in S. aureus standard strain Newman (fig. S1). Furthermore, using the viable cell count method, we found a significant 1.2 to 8.5 log10 decrease of CFU/ml in S. aureus biofilms treated with 0.5× to 8× MIC of ChryA, when compared with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)–treated biofilms (Fig. 2F). This was confirmed by complete eradication of living cells after being exposed to ChryA at 8× MIC using SYTO 9/PI (propidium iodide) double staining (Fig. 2G). As a control, vancomycin showed no antibiofilm ability against S. aureus. Overall, these results first demonstrated that ChryA had the potential to eradicate the persister reservoir and exerted significantly superior antibiofilm effects.

ChryA is effective in murine epicutaneous infection model

Given the promising activity of ChryA in vitro, we sought to determine whether it can function as an effective antibiotic in vivo. We first established a murine epicutaneous infection model in BALB/C mice that were infected intradermally with S. aureus MRSA strain USA300 (Fig. 3A) (32). The bacterial burden was determined by homogenizing the infected skin lesion and plating the serially diluted samples on Luria-Bertani (LB) plates 1 day (day 6) and 11 days (day 16) after infection, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3B, on day 6, topical application of ChryA significantly killed bacteria in a dose-dependent manner. Treatment with ChryA at 1, 3, and 9 mg kg−1 resulted in approximately 1.5-log10 (P < 0.01), 4.8-log10 (P < 0.0001), and 7.2-log10 (P < 0.0001) decreases in bacterial burden per wound, respectively. On day 16, a similar killing effect was also observed with an average burden reduction of 1.8 log10 and 3.1-log10 (P < 0.0001) CFU/wound after treatment with ChryA at 3 and 9 mg kg−1, respectively (Fig. 3C). Methicillin (3 mg kg−1) served as a positive control, showing no significant killing effect compared to the vehicle control. These results indicate that ChryA had a long-lasting anti-MRSA effect in vivo even after 10 days of treatment. The wound scabbing and necrosis were noticeably improved, and the lesion size was significantly reduced when compared with the vehicle controls. In particular, the mice treated with ChryA at 9 mg kg−1 showed almost completely healed wounds on day 16 (Fig. 3, D and E).

Fig. 3. In vivo efficacy of ChryA against MRSA USA300 infection in a murine epicutaneous infection model.

(A) Schematic diagram for examining the efficacy of ChryA in a mouse model infected by S. aureus USA300. (B and C) ChryA reduces the bacterial loads in skin wound infections. CFUs of colonized S. aureus in wounds 1 day (day 6) (B) and 11 days (day 16) (C) after infection were counted. (D) Representative images showing necrotic skin lesions after infection. (E) The wound area was calculated with ImageJ software and the lesion sizes of the vehicle and ChryA treatment groups on day 16 were used for data statistics. Met, methicillin. All the data are presented as averages ± SD. Statistical differences between control and antibiotic treatment groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (**P < 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001).

Last, the potential adverse effects of ChryA were assessed. Hematoxylin and eosin revealed multiple sites of abscess formation with bacterial clusters localized to the scalpel wound sites in the vehicle (1% DMSO) group; however, mice treated with ChryA had less demarcated abscesses and reduced bacterial invasion in skin sections (fig. S2A). There were no notable changes in mouse body weight following treatment (fig. S2B), indicating the low toxicity of ChryA in vivo. In addition, fusidic acid, a common topically applied antibiotic that served as a positive drug (MIC = 0.031 μg/ml), exhibited less effectiveness compared to the low dose of ChryA (fig. S3). Overall, these findings demonstrated that ChryA can reduce the bacterial load in the wound of the MRSA-infected mouse model, accelerate wound healing, and minimize recurrence.

Supplementation with exogenous lysine, proline, or uridine diphospho-N-acetylglucosamine rescues impaired S. aureus growth by ChryA

To elucidate the MoA of ChryA against S. aureus, we sought to isolate spontaneous resistant mutants for target identification. Plating S. aureus Newman on Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar plates containing ChryA at 8× MIC produced resistant mutants with a frequency of approximately 1 × 10−9. After multiple passages of S. aureus Newman with ChryA, we isolated 10 resistant clones, all of which had a MIC of ChryA at least fourfold higher than the parent strain and were as sensitive as the Newman strain to ciprofloxacin and penicillin G (Fig. 4, A and B). Whole-genome sequencing revealed that five mutants (M1 to M5) from early passages with four- to eightfold increases in MIC that were only modest, contained mutations in dapD encoding tetrahydrodipicolinate N-acetyltransferase essential for lysine production (33) and proC encoding pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase essential for proline production (34) (Fig. 4B and table S2). The other three mutants (M8 to M10) obtained from the final passages showed a large increase (64- or 128-fold) in MIC and harbored extra mutations in four genes: glmU encoding glucosamine-1-phosphate acetyltransferase/UDP-N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase for uridine diphospho-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc; a key precursor molecule of cell wall peptidoglycan) production (35), rpoC encoding RNA polymerase β′ subunit (36), and NWMN_0676 and NWMN_1816 encoding two proteins of unknown functions that are conserved among Staphylococcus species. We then measured changes in ChryA sensitivity in S. aureus cells overexpressing each protein using the plasmid pYJ335 (37). Spot dilution assays showed that overexpression of each protein rendered S. aureus cells more resistant to ChryA (Fig. 4C). The increased ChryA resistance toward the overexpression strains was confirmed by 4- to 32-fold increase in MIC values compared with the parent strain carrying the empty vector (fig. S4A). As expected, the overexpression of each protein had no effect on ciprofloxacin or penicillin G sensitivity (fig. S4A), suggesting that all these proteins were the potential targets of ChryA, but not of ciprofloxacin and penicillin G.

Fig. 4. Target identification of ChryA in S. aureus.

(A) Schematic representation of the resistance development assay. (B) Schema of whole-genome sequencing list of mutations in the spontaneous ChryA-resistant clones M1 to M10. (C) Resistant spot dilution assays for S. aureus RN4220 overexpressing putative target genes on Mueller-Hinton (MH) plates containing indicated concentrations of ChryA. The parent strain RN4220 and RN4220 carrying the empty vector pYJ335 were used as negative controls. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (D) Exogenous addition of corresponding final biosynthetic products of DapD, GlmU, and ProC alleviated the bactericidal activity of ChryA against S. aureus Newman. The MIC value of ChryA was examined when supplemented with 40 mM lysine, 100 mM proline, and UDP-GlcNAc alone or in combinations, respectively. (E) Growth rescue experiments were performed with exponential-phase S. aureus Newman in the presence of 0.5× MIC of ChryA. The S. aureus Newman culture was supplemented with each product as (D), and CFUs were counted after 6 hours of incubation. (F) The muramic acid content of isolated sacculi was quantified after treatment with indicated concentrations of ChryA, ciprofloxacin, and fosfomycin, respectively. Fosfomycin and ciprofloxacin were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. All assays in (E) and (F) were performed with three biologically independent experiments, and the mean ± SD is shown. Statistical differences between control and antibiotic treatment groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (*P < 0.05 and ****P < 0.0001).

To further confirm the attribution of dapD, proC, and glmU to the resistance of ChryA, we determined whether their corresponding final biosynthetic products could rescue S. aureus growth impaired by ChryA. A significant elevation in viability was observed for ChryA-treated S. aureus cells when supplemented with lysine, proline, or UDP-GlcNAc alone (fig. S4B). This result was in agreement with a 2 to >16 increase in MIC values of ChryA in the presence of each of them (Fig. 4D). Note that lysine and UDP-GlcNAc had a greater effect on ChryA-treated cellular viability than proline. As a control, the sole addition of lysine or UDP-GlcNAc did not affect S. aureus susceptibility to ciprofloxacin and penicillin G (fig. S4C). In addition, no changes in ChryA sensitivity were detected when supplemented with each of the rest of the essential amino acids (except Trp; fig. S4D), suggesting that lysine and proline biosynthesis is the crucial targets specific to ChryA. Moreover, supplementation of three mixed products or lysine plus UDP-GlcNAc restored S. aureus growth more efficiently than sole of them (P < 0.0001; Fig. 4E). Thus, we hypothesized that ChryA has a complex MoA involving multiple molecular targets, which is distinct from known classes of antibiotics.

ChryA inhibits peptidoglycan precursor biosynthesis by targeting GlmU and DapD

As glmU and dapD both are essential genes in S. aureus (38) and their synthetic products UDP-GlcNAc and lysine are essential for building up the cell wall peptidoglycan, it is reasonably inferred that ChryA interferes with peptidoglycan production. In this study, peptidoglycan quantification was determined from the muramic acid content of isolated saccule (39, 40). As expected, treatment with 1× MIC of ChryA resulted in a 93.3% reduction in peptidoglycan content compared with the DMSO-treated control (Fig. 4F). A similar result was also observed with 1× MIC of fosfomycin (41), an inhibitor of the UDP-N-acetylglucosamine-enolpyruvyl transferase enzyme MurA, which catalyzes the first committed step in peptidoglycan biosynthesis (42). Moreover, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observations indicated that the cell wall integrity of S. aureus was severely impaired by ChryA and fosfomycin, followed by bacterial cell lysis when treated within 4 hours (fig. S5A). Moreover, the dynamics of the permeability of the cell membrane and membrane potential were recorded in S. aureus. The addition of ChryA caused no evident changes in cell membrane permeability (fig. S5B) and depolarization (fig. S5C), whereas the positive control Gramicidin treatment did, which is in agreement with previous studies (43, 44). Together, these results implied that like fosfomycin, ChryA inhibited peptidoglycan precursor biosynthesis and thus changed the architecture of the cell wall, but not the cell membrane, of S. aureus.

To learn whether ChryA inhibits enzymatic activities of GlmU and DapD (Fig. 5, A and B) through direct binding, we purified recombinant GlmU and DapD (fig. S6) and measured the glucosamine-1-phosphate and tetrahydrodipicolinate acetyltransferase activities with acetyl-CoA as substrates, respectively. In this assay, ChryA inhibited GlmU- and DapD-dependent acetyltransferase activities with an apparent half-maximum inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 8.46 ± 0.93 and 4.03 ± 0.92 μM (Fig. 5, C and D), respectively. To quantify ChryA interaction with GlmU or DapD, we measured the binding affinity using microscale thermophoresis (MST) analysis. The result of this analysis revealed strong binding of GlmU with ChryA [dissociation constant (Kd) = 4.61 ± 2.38 nM; Fig. 5E]. In addition, a Kd value of 2.85 ± 1.90 nM was obtained for DapD with ChryA (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 5. Molecular mechanism underlying ChryA inhibition of GlmU and DapD activities.

(A and B) The proposed reaction was catalyzed by GlmU (A) and DapD (B) in S. aureus. (C and D) IC50 determination for inhibition of GlmU (C) and DapD (D) acetyltransferase activities by ChryA. (E and F) MST measurements of GlmU (E) and DapD (F) binding with ChryA. Normalized fluorescence (ΔFnorm) from three independent experiments, with SD shown, was plotted against the concentration of ChryA. Data analysis was performed with the MO. Affinity Analysis software (NanoTemper Technologies) using the Kd model. (G and H) Kinetic analysis of the inhibition mechanism of ChryA on GlmU (G) and DapD (H) acetyltransferase activities. The two panels show representative Lineweaver-Burk plots of 1/rate (1/V) versus 1/substrate (acetyl-CoA) concentration in the presence of varying concentrations of ChryA. The Lineweaver-Burk plots were created by GraphPad Prism 7. (I and J) Normalized residual activity of GlmU, GlmU G277S (I) and DapD, DapD A219Q (J) in the absence and presence of 12.5 μM ChryA. All the data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical differences were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (**P < 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001).

To further explore the interaction mechanism of ChryA with GlmU and DapD, their kinetics inhibition was performed using Lineweaver-Burk plots. The results showed that ChryA is a competitive inhibitor with regard to the substrate acetyl-CoA with inhibitory constant Ki values of 22.33 ± 2.38 and 9.13 ± 0.13 μM for GlmU and DapD (Fig. 5, G and H), respectively. This inhibition pattern suggested that ChryA inhibits the acetyltransferase activities of GlmU and DapD by competition with their mutual substrate acetyl-CoA. Thus, ChryA inhibited GlmU and DapD acetyltransferase activities and interfered with the upstream raw materials of peptidoglycan biosynthesis, thus impeding peptidoglycan synthesis and cell growth.

GlmU G277S and DapD A219Q substitutions are involved in resistance to ChryA

Whole-genome sequencing identified a missense mutation in glmU and dapD causing a glycine (G) to serine (S) substitution at amino acid position 277 and an alanine (A) to glutamine (Q) substitution at amino acid position 219, respectively (table S2). We then determined whether the two amino acid substitutions confer ChryA resistance in S. aureus. As shown in Fig. 6A, the RN4220 strains overexpressing GlmU G277S and DapD A219Q variants exhibited much more resistance to ChryA than those with the wild-type proteins, respectively. The increased ChryA resistance was confirmed by a fourfold increase in MIC values compared with the parent strain expressing the wild-type proteins (Fig. 6B). We also performed allelic replacement to generate the glmU(G277S) and dapD(A219Q) glmU(G277S) chromosomal mutants to further confirm this result. The susceptibility of the wild-type and the two mutant strains together with the mutant M1 (dapD A219Q) to ChryA was evaluated by plate sensitivity assay and MIC determination. As expected, the three mutants were more resistant than the wild-type strain (Fig. 6, C and D). GlmU G277S and DapD A219Q substitutions seemed to confer a similar level of resistance to ChryA. In addition, the allelic replacement of the native protein with both amino acid substitutions exhibited increased resistance to ChryA compared with a single substitution (Fig. 6, C and D).

Fig. 6. GlmU G277S and DapD A219Q substitutions confer resistance to ChryA.

(A) Resistant spot dilution assays for S. aureus RN4220 overexpressing mutant genes on MH plates containing indicated concentrations of ChryA. The parent strain RN4220 and RN4220 carrying the empty vector pYJ335 were used as negative controls. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Overexpression of GlmU G277S and DapD A219Q variants increased MICs of ChryA compared to the wild-type protein. Ciprofloxacin and penicillin G served as negative controls. (C) Resistant spot dilution assays for the wild-type strain (Newman), M1 (dapD A219Q), BHKS709 (glmU G277S), and BHKS710 (dapD A219Q and glmU G277S) on MH plates containing indicated concentrations of ChryA. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (D) The fold change of MIC for ChryA against the wild-type and three mutant strains. (E) The relative exponential growth rate of the wild-type and three mutant strains in the absence or presence of ChryA. Error bars correspond to SD among measurements for independent growth assays for three individual colonies. Statistical differences between the wild-type strain and each mutant were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (****P < 0.0001).

We next tested the glucosamine-1-phosphate acetyltransferase activity of the GlmU G277S variant without and with the treatment of ChryA. As shown in Fig. 5I, the mutation of Gly277 to Ser resulted in a loss of ca. 68% of the acetyltransferase activity without treatment of ChryA, suggesting the essential role of this residue for the catalytic activity of GlmU. As expected, the addition of ChryA weakened the activity of GlmU by 62%, while for the G277S variant, no significant decrease in enzyme activity was observed. Moreover, the IC50 of ChryA for the G277S variant was increased 3.1-fold to 26.13 ± 0.93 μM (Fig. 5C), in agreement with Kd of 48.06 ± 6.24 nM for the variant that is 10.4-fold higher than the wild-type GlmU (Fig. 5E). In addition, we also confirmed that Ala219 was the active residue for DapD activity (Fig. 5J). The DapD A219Q variant showed an IC50 of 22.12 ± 0.9 μM for DapD-dependent acetyltransferase activity, 5.5-fold higher than the wild-type protein (Fig. 5D). According to the MST fitted curves, an increased (14.2-fold) Kd value was obtained for the variant, compared with that for wild-type DapD (Fig. 5F), suggesting a remarkably decreased binding affinity of ChryA with the variant. These results indicated that GlmU Gly277 and DapD Ala219 are the key residues for ChryA-mediated inhibition of GlmU- and DapD-dependent acetyltransferase activities, respectively. Note that the ProC T216S and MWMN_1816 M32I variants also displayed approximately a threefold reduction in affinity toward the ChryA, compared with wild-type proteins (fig. S7).

Given the two lowered essential enzyme activities by the G277S and A219Q substitutions, relative growth rates were examined to determine the fitness effects of the mutations in S. aureus. These three resistant mutants resembled the growth of the wild-type strain in the absence of ChryA and showed no general fitness reduction (Fig. 6E). This result indicated that the low enzyme activity of the GlmU (G277S) and DapD (A219Q) variants, alone or together, supports normal growth in S. aureus. As expected, the success of these mutants with improvements in growth performance over the wild-type strain in the presence of a sublethal level of ChryA was reflected by large fitness benefits conferred by these variants (Fig. 6E).

DISCUSSION

The current antibiotic crisis and lack of commercially available antipersister therapies have rekindled the interest in antipersister drug development. Recently, several small molecules (45–47), antimicrobial peptides (48, 49), and U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved human kinase inhibitor sorafenib (50) have been disclosed to inhibit S. aureus persisters and biofilms. Although the antimicrobial properties of ChryA were well documented before our study, this compound has never been tested on persister cells. Our study first provided strong evidence that ChryA is a bactericidal antibiotic attacking both metabolically active and biofilm-encased persister cells of S. aureus. Moreover, our results demonstrate that ChryA acts by targeting multiple proteins, thus interfering with multiple metabolic pathways, including lysine, proline, and peptidoglycan precursor biosynthesis (Fig. 7), as well as two unknown pathways involving NWMN_0676 and NWMN_1816, to exert its bactericidal effect against S. aureus.

Fig. 7. Diagram showing that ChryA kills S. aureus by targeting multiple essential pathways involving lysine, proline, and peptidoglycan precursor biosynthesis.

Direct killing of persister cells is one of the main antipersister strategies, which includes destroying the cell wall and depolarizing the cell membrane, inhibiting essential enzymes, DNA cross-linking, and generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) (29). Recently, growing data showed that the production of intracellular ROS implies a vital effector role in persister cell death (51). Here, we discovered that ChryA triggers the accumulation of ROS in a dose-dependent manner (fig. S8, A, and B), and ChryA-induced cell death of S. aureus is accompanied by DNA fragmentation (fig. S8C) and chromosome condensation (fig. S8D). Bactericidal antibiotics have been proposed to kill bacteria by a common mechanism involving the generation of ROS (52, 53). Although this theory has been in debate (54, 55), this ROS-mediated damage in S. aureus by ChryA could result from the interaction of ChryA with its multiple targets and enhance its antipersister-killing efficacy. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that ChryA directly damages S. aureus DNA because a previous study identified ChryA as a DNA-intercalating agent that initiated DNA damage upon exposure to light (21).

Recent efforts have reinvigorated antibiotics research, but most of them have resulted in compounds that function via mechanisms similar to traditional antibiotics and quickly develop resistance (56). Thus, there is an urgent need to develop new classes of antibiotics with novel targets or MoA to avoid cross-resistance to established targets. One target of antibacterial agents that has yet to be exploited clinically is bacterial lysine biosynthesis which starts from l-aspartate and enters into the diaminopimelate (DAP) pathway to produce the lysine precursor meso-DAP. The produced lysine and meso-DAP are essential for protein synthesis and construction of the bacterial cell wall (57). In this study, whole-genome sequencing of spontaneous ChryA-resistant mutants and growth rescue experiments indicated that ChryA targets lysine production, thus inhibiting peptidoglycan precursor biosynthesis. In the prokaryotes, the DAP pathway consists of four variant pathways: the succinylase (58), acetylase (59), dehydrogenase (60), and aminotransferase pathways (61). The branch point between the most common succinylase and acetylase pathways is the key enzyme DapD. Like most species, DapD of Escherichia coli only catalyzes the committed step of the succinylase route and uses three key residues (Gly163, Arg187, and Glu189) required for succinyl group recognition (fig. S9) (62). Through the analysis of the S. aureus genome, we found that S. aureus contains complete gene sets of the DAP pathway, and dapD is annotated as a tetrahydrodipicolinate N-acetyltransferase (THDP-AT) mainly on the basis of the acetyl group recognition by three different residues (Val154, Asn178, and Val180) from those of EcDapD, suggesting the existence of the acetylase pathway in S. aureus. Crucially, we reconstructed the enzymatic reaction of the THDP-AT enzyme DapD of S. aureus in vitro and revealed that ChryA was a competitive inhibitor that directly binds to DapD. To the best of our knowledge, ChryA was the first molecule discovered that can inhibit the acetyltransferase activity of DapD in bacteria, and such an inhibitor may provide a new class of antibacterial agents.

In addition, we uncover that biosynthesis of UDP-GlcNAc, an essential precursor for bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan, serves as another vital pathway targeted by ChryA in S. aureus. The bifunctional enzyme GlmU catalyzing the last two steps of this pathway has been proposed as a potential drug target for the antibacterial agent development (63, 64). In this study, ChryA was shown to bind to GlmU of S. aureus and to inhibit its acetyltransferase activity in a competitive manner. We speculate that Gly277 was the key residue of GlmU for ChryA-mediated inhibition of the catalytic activity based on several findings: the essential role of this residue for the catalytic activity, the increased resistance to ChryA, and the decreased binding affinity of ChryA for the G277S variant. Gly277 was located in the C-terminal acetyltransferase domain of GlmU (fig. S10), which adopts a left-handed parallel β-helix structure (LβH) in homologous bacterial acetyltransferases (65), and is highly conserved in Staphylococcus species. Thus, ChryA may inhibit the acetyltransferase activity of GlmU by targeting Gly277 in the active site.

It is known that peptidoglycan synthases and hydrolases coordinate to ensure cell growth and division (66). Loss of either peptidoglycan synthesis or hydrolysis in S. aureus is lethal because of the continued activity of the other, but the loss of both will result in stasis (67). Here, we assumed that the MoA of ChryA involves blocking peptidoglycan synthesis by targeting DapD and GlmU in the presence of peptidoglycan hydrolases. Besides them, ChryA may have four extra protein targets: ProC, RpoC, NWMN_0676, and NWMN_1816. Although overexpression of each of them conferred S. aureus resistance to ChryA, the interactions between ChryA and them and functional elucidation of NWMN_0676 and NWMN_1816 warrant further studies, which may allow target confirmation for antibiotic discovery.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that ChryA exhibited a potent antipersister and antibiofilm activity with extraordinary killing effect of MRSA strains in vitro and in vivo. This unique anti–S. aureus activity of ChryA may thereby diminish the recalcitrant nature of infections, allow the eradication of biofilm infections, and overall result in a reduction of antibiotic treatment duration. Moreover, previous studies have shown that ChryA has low toxicity (19, 68) and could decrease the levels of proinflammatory factors (27), but further experiments are still required to evaluate the drug-like profile, including safety and Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Excretion (ADME) properties. It is encouraging that continuous efforts have been devoted to optimizing the ChryA formula development to enhance the solubility and oral bioavailability (25, 69), highlighting the promising application of ChryA in efficacious topical treatment for MRSA skin infections. This promising drug lead proposes that coupling multiple MoAs on one small molecule may be an underappreciated approach to combat drug-resistant S. aureus persisters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture media

The bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in tables S3 and S4. Unless otherwise stated LB medium was used for the cultivation of all S. aureus and E. coli strains at 37°C aerobically. TSB medium (Tryptic Soy Broth, Solarbio) was used for the antibiofilm assay. B2 broth (1.0% casein hydrolysate, 2.5% yeast extract, 0.1% K2HPO4, 0.5% glucose, and 2.5% NaCl) (70) was used for the cultivation of transformed S. aureus RN4220 (71). RPMI 1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) was used for the cultivation of Candida albicans strains. MH broth (Oxoid) was used to cultivate other bacterial strains for antibacterial activity determination. For plasmid maintenance, antibiotics were used at the following concentrations where appropriate: for S. aureus, erythromycin at 10 μg/ml, and for E. coli, ampicillin at 100 μg/ml, kanamycin at 50 μg/ml, chloramphenicol at 30 μg/ml, and erythromycin at 200 μg/ml.

Chemicals

ChryA (≥96%) was obtained by fermentation, subsequent extraction, and purification as described previously (72). Other reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial suppliers (Sigma-Aldrich, MDBio, Oxoid, Solarbio, MCE, Invitrogen, Aladdin, QIAGEN, Promega, Genmed Scientifics Inc., and Beyotime) and used as received unless otherwise indicated.

Construction of plasmids

To construct the plasmid for the constitutive expression of each target gene, a DNA fragment covering the Shine-Dalgarno sequence of the upstream region and each gene was amplified from S. aureus Newman genomic DNA with the indicated primers (table S4) and then cloned into pYJ335 (37). The construct with each gene in the same orientation as the tetracycline-inducible xyl/tetO promoter was confirmed by DNA sequencing, yielding plasmids pBHK480, pBHK481, pBHK482, pBHK483, pBHK484, and pBHK485, respectively. The recombinant plasmid was each electroporated into the S. aureus strain RN4220, and then, the transformant was screened on B2 agar plates supplemented with erythromycin (10 μg/ml). The plasmid expressing each protein variant was constructed and electroporated into the S. aureus strain RN4220 with a similar method.

Construction of recombinant chromosomal mutants

To construct the glmU(G277S) and dapD(A219Q) glmU(G277S) chromosomal mutants, the plasmid pKOR1 was used as previously described (73). By using the indicated primers (table S4) and the genome of the S. aureus M10 mutant strain as a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) template, a 2-kb target fragment (1 kb of both the upstream and downstream regions of the mutation site) was amplified using Gateway BP Clonase II Enzyme Mix (Invitrogen) to generate plasmid pBHK534. After verification by DNA sequencing, the plasmid was first introduced into S. aureus strain RN4220 for modification and subsequently transformed into S. aureus Newman and M1 mutant, respectively. The allelic replacement mutants BHKS709 (glmU G277S) and BHKS710 (dapD A219Q and glmU G277S) were selected by a two-step procedure as previously described (73), and the glmU (G277S) mutation was further confirmed by PCR and sequencing.

Minimum inhibitory concentration

The MIC was determined by a broth microdilution assay according to the CLSI broth microdilution method (M07-A10). Twofold serial dilutions of the test compounds were prepared in a 96-well microtiter plate containing 100 μl of media. In the case of S. aureus, cultures were grown at 37°C with shaking in MH broth to midlogarithmic phase [optical density at 600 nm (OD600) = 0.4 to 0.6] and diluted into MH broth to give a final concentration of approximately 1 × 105 CFU/ml. After incubation at 37°C for 16 to 24 hours, the dilution series were analyzed for microbial growth. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentrations of antibiotics with no visible growth of bacteria. To determine the MIC in the presence of exogenous amino acids or UDP-GlcNAc (Aladdin, China), the pH of the MH broth is adjusted to 7.0 to 7.4, if necessary. For comparison, the antibiotic vancomycin was also tested.

For C. albicans, the MIC was determined according to the CLSI (M27-A2) guideline. Briefly, a 0.1-ml yeast inoculum of 1.0 (±0.2) × 103 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium was added to each microdilution well. Growth inhibition was determined by measuring the OD530 after incubation at 30°C for 24 hours. MIC was determined by measuring the concentration required to inhibit the growth of 90% of C. albicans' planktonic cells. All MIC assays were performed in duplicate and repeated with three independent experiments.

Time-killing assays

An overnight culture of S. aureus Newman was diluted in LB broth and grown to midlogarithmic phase (OD600 = 0.4 to 0.6) at 37°C with shaking. Subsequently, cells were diluted to 1 × 106 CFU/ml in LB broth containing various concentrations of ChryA or vancomycin. Cells were incubated at 37°C with shaking, and serial dilutions were plated on LB agar plates at indicated time points for the determination of viable cells (CFU/ml). Each assay was performed in duplicate and repeated with three independent experiments.

Persister cell assays

Effect of ChryA on stationary-phase persister cells

S. aureus Newman cells were grown in LB medium at 37°C with shaking for 24 hours. Stationary planktonic cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 1 ml of sterile PBS to a concentration of approximately 1 × 109 CFU/ml and treated with various concentrations of ChryA, 100× MIC of ciprofloxacin (MIC = 0.5 μg/ml, MCE), 100× MIC of penicillin G (MIC = 0.125 μg/ml, MCE) or DMSO for 12 hours at 37°C. At indicated time points, samples were withdrawn, harvested, washed with sterile PBS three times, and resuspended in sterile PBS for the determination of CFU/ml by plating serial dilutions on LB agar plates.

Effect of ChryA on antibiotic-induced persister cells

This assay was performed as described previously with modifications (74). Overnight, S. aureus Newman cultures were diluted 1:100 in fresh LB broth and grown at 37°C to reach the exponential phase (OD600 = 0.4 to 0.6). Cells were then washed three times with sterile PBS and resuspended in 1 ml of sterile PBS to give a final concentration of approximately 1 × 109 CFU/ml. Subsequently, ciprofloxacin or penicillin G was added to cell cultures to a final concentration of 10× MIC. After incubation at 37°C for 6 hours, the antibiotic-induced persister cells were harvested, washed, resuspended in 1 ml of PBS containing 2× MIC of ChryA and 10× MIC of ciprofloxacin or penicillin G, and incubated for 3 hours at 37°C. At the designated time points, aliquots (100 μl) of culture were taken out and washed with PBS. The total number of surviving bacteria was determined by plating serial dilutions of the bacteria on LB agar plates. Viable bacterial colonies on plates were enumerated and expressed as CFU/ml.

Antibiofilm assay

The effect of ChryA on S. aureus biofilm formation was examined in 96-well microtiter plates using a crystal violet method to stain adherent cells. S. aureus USA300 was grown overnight, diluted to an OD600 of 0.01 with fresh TSB, and then used to fill triplicate wells of a sterile 96-well microtiter plate. Various doses of ChryA and vancomycin were added to the wells above and an equivalent amount of DMSO was used as a vehicle control. Following static incubation for 18 hours at 37°C, the culture medium was removed by aspiration, and the plate was washed twice with PBS. Then, 100 μl of 0.5% crystal violet was added to each well, followed by incubation at room temperature for 15 min. After removing the excess crystal violet solution, biofilms were washed with PBS three times, and the remaining coloring agent was dissolved in 95% ethanol in ddH2O (200 μl). The optical density was measured at 595 nm using a Synergy HTX multimode microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). All measured values were normalized to values resulting from DMSO-treated samples (100% biofilm). To examine the effect on biofilm eradication, S. aureus biofilms were allowed to develop in the absence of the compound for 18 hours, after which nonbiofilm material was removed by washing with PBS. Fresh TSB medium supplemented with the tested agents was added. After an additional 4 hours, the biofilms were washed and quantified by the crystal violet staining method as described above. Data were obtained from three independent experiments with triplicate runs for each concentration.

Assessing the cell viability of S. aureus biofilms

The effect of ChryA on the cell viability of preformed biofilms was investigated using colony count methods. Biofilms of the S. aureus cells were prepared and treated with various doses of agents followed by 4 hours at 37°C as described above. After incubation, additives were removed, and the biofilms were detached by scraping wells entirely with a 200-μl pipette tip across the well. The scraped biofilms were then homogenized in a TSB medium by repeatedly pipetting the solution several times. Last, the homogenized biofilm suspensions were serially diluted, spread out onto LB agar plates, and incubated at 37°C. Viable bacterial colonies on plates were enumerated and expressed as CFU/ml.

Bacterial viability within the biofilm was also assessed using a LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit (Invitrogen, Molecular Probes, USA), consisting of two fluorescent dyes, SYTO9 and PI. Biofilms of the S. aureus cells were prepared and treated with various doses of agents followed by 4 hours at 37°C as described above. The nonadherent cells were then washed with PBS twice and stained with the two fluorescent dyes for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. After rinsing, the images were observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 710; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), and more fields of view were examined randomly. The intact cell membranes are stained in green, whereas cells with damaged cell membranes stain fluorescent red because of the intracellular accumulation of PI.

Murine epicutaneous infection model

The murine epicutaneous infection model was carried out on the basis of previous studies (32) with some modifications. The in vivo protocol design and procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Nanjing Medical University under ethical protocol approval no. IACUC-2104038. Six-week-old specific pathogen–free female BALB/c mice were used in this study. Mice were obtained from the Animal Core Facility, Nanjing Medical University, China, and housed at the same place. BALB/c mice (n = 9 mice in each group) were anesthetized with pentobarbital (30 mg/kg), shaved on the back, and injected intradermally with S. aureus USA300 (1.5× 108 CFUs) in 50 μl of sterile PBS using a syringe on day 1. Two days after infection (day 3), 25 μl of 1% DMSO (vehicle), methicillin in 1% DMSO (3 mg/kg per day), or various concentrations of ChryA in 1% DMSO (1, 3, and 9 mg/kg per day) were injected to the wounds twice per day for three consecutive days. The wound size was recorded on the indicated days (days 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16). On days 6 and 16, mice were anesthetized and euthanized. To enumerate viable bacteria, the whole lesioned skin specimens were excised with sterile scissors (including all accumulated pus) and homogenized in 1 ml of sterile LB, and the suspension was serially diluted and plated on LB agar plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C overnight to count the bacterial burdens. For histopathological studies, the skin biopsy samples were taken after mice were euthanized and fixed in PBS (pH 7.4) with 4% formalin. The formalin-fixed biopsy samples were embedded in paraffin, and the sections were obtained and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Resistance development assay

The ChryA-resistant development assay was performed in tubes containing 5 ml of LB broth containing progressively increasing concentrations of ChryA as described previously (75) with modifications. Briefly, S. aureus Newman cell cultures (108 CFU/ml) were first passaged in LB broth containing 0.5× MIC of ChryA and incubated for 24 hours with shaking at 37°C. After each passage, the tube showing substantial growth was used to inoculate the subsequent culture containing the same or twice the prior concentration of ChryA. At selected passages, the S. aureus Newman cells from the tube with the higher ChryA concentration showing visible bacterial growth were streaked onto LB agar plates containing various concentrations of ChryA and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. Single colonies were isolated, passaged five consecutive passages on drug-free LB plates, subjected to standard MIC testing, and stored at −80°C for whole-genome sequencing. In this study, five independent experiments were performed and 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 rounds of passages were used for each independent experiment. Two single colonies were obtained from two repeats of each independent experiment, and a total of 10 mutants were selected as ChryA-resistant colonies M1 to M10.

Whole-genome sequencing

Ten selective ChryA-resistant colonies from the agar plates were cultured overnight. A single isolate from the reference strain S. aureus Newman was also selected for sequencing. Genomic DNA was extracted using Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA was sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 instrument using 2 × 150–base pair paired-end reads by Allwegene Technologies Corporation, Beijing, China. After sequencing, the raw FASTQ sequence reads were filtered, including removing adapter sequences, contamination, and low-quality reads with more than 10% N base calls or where more than 50% of the bases have a quality score ≤5. Sequencing coverage was determined using the FASTQC quality control tool version 0.10.1. The proportion of bases sequenced with a sequencing error rate of 1% or less per base ranged from 0.02 to 0.03% per genome. The average coverage depth for the remaining 11 sequenced strains was 50×, and the average percentage of bases covered by at least one read was 96.49%. After sequencing, efficient sequencing was compared with reference genomes using BWA software, and then, the repeated reads were marked using SAMtools software. The SAMtools were also used to detect single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and filter SNPs with PE reads less than 4. The single-nucleotide variants in the reference strains were filtered from the resistant strains to identify the selective mutations that contributed to resistance. The mutations were observed and listed in table S2.

Protein expression and purification

The target protein-coding regions were amplified with primers and inserted into the expression vector pQE-2 with an N-terminal hexahistidine tag to generate eight plasmids from pBHK466 to pBHK473. The constructed recombinant plasmids were transformed into the host strain E. coli Rosetta pLysS and grown at 37°C in LB medium in the presence of kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml). The bacterial cultures were induced with 0.2 mM isopropyl-β-d-thio-d-galactoside at an OD600 of 0.8 and were grown at 37°C for an additional 3 hours before harvest. The cells were collected, resuspended in lysis buffer [50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, and 1 mM dithiothreitol (pH 8.0)], lysed by sonication, and centrifuged. The clarified bacterial supernatant was loaded onto a nickel-ion affinity column (QIAGEN). The column was washed with wash buffer [50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole, and 1 mM dithiothreitol (pH 8.0)] and eluted in the same buffer (elution buffer) containing 200 mM imidazole. The protein was concentrated by ultrafiltration (10-kDa cutoff) and exchanged into sodium phosphate buffer [50 mM sodium phosphate, 200 mM NaCl, and 1 mM dithiothreitol (pH 8.0)]. The purity of the samples was monitored by SDS-PAGE. Strains, plasmids, and primers used for protein overexpression are listed in tables S3 and S4.

Resistant spot dilution assays

The plasmid-borne S. aureus RN4220 strains were cultured in LB medium and grown to midlogarithmic phase at 37°C. Bacterial cells were resuspended in PBS and were adjusted to an initial density at OD600 of 0.1, and serial dilution was performed using fresh MH broth. For each dilution, 3 μl was spotted on the MH agar plate containing tetracycline (35 ng/ml) to induce protein expression and various concentrations of ChryA. Bacterial growth was visually observed on plates with or without ChryA after 24 hours at 37°C. The assays were repeated with three independent experiments.

IC50 measurement

The acetyltransferase activity of S. aureus GlmU was measured by Ellman’s Reagent (DTNB; Sigma-Aldrich) colorimetric assay according to the protocol published earlier (76). The reaction product–free CoA reacts with DTNB to release 4-nitrothiophenolate, which was quantified at 412 nm. Briefly, 2 μl of twofold serial ChryA dilution (10 mM, 5 mM, 2.5 mM, 1.25 mM, 625 μM, 312.5 μM, 156 μM, 39 μM, and 9.76 μM in DMSO) were added to clear polystyrene 96-well plates (Corning, NY) and preincubated with 60 nM purified S. aureus Newman GlmU or GlmU A277S (37°C and 10 min) before the start of the reaction. Enzyme reactions were performed in a 100-μl volume containing 225 μM acetyl-CoA (Sigma-Aldrich) and 225 μM d-glucosamine1-phosphate (TRC, China) in the assay buffer, which consists of 50 mM MOPS-NaOH (pH 7.35), 75 mM potassium acetate, 10 mM MgCl2, and 0.005% Tween 20. Reactions were incubated for 30 min at 37°C and then quenched with 50 μl of 1.5 mM Ellman’s reagent in 0.1 M sodium phosphate (pH 7.2). The absorbance at 412 nm was measured after 5 min with a Synergy HTX multimode microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). Data were obtained from three independent experiments with triplicate runs for each concentration. Percent residual activity was calculated using the following equation: residual activity (%) = 100 × (A412nm − Blank)/(Max-Blank), where A412nm is the absorbance in the test well, Blank is the absorbance of each reaction without enzyme, and Max is the absorbance of the uninhibited reaction (DMSO-treated). A log substrate concentration versus percent residual activity (XY) graph was created using GraphPad Prism 7. The compound concentration resulting in 50% inhibition (IC50) was calculated by nonlinear least squares regression to the equation: 1 − Y = 100/{1 + 10[(logIC50−X)×HillSlope]}, where Y is the percent residual activity and X is the log inhibitor concentration.

For DapD acetyltransferase activity, the formation of free CoA was also monitored by Ellman’s Reagent (DTNB) colorimetric assay. Enzyme reactions were performed in a 100-μl volume containing 200 μM acetyl-CoA (Sigma-Aldrich), 5 mM 2-aminopimelic acid (the substrate analog of tetrahydrodipicolinate, Macklin) (77), and 400 nM S. aureus Newman DapD or DapD A219Q in assay buffer. The IC50 measurement was carried out using the mentioned method above.

Kinetic mode of inhibition

The mode-of-inhibition and inhibition constant (Ki) values were determined by simultaneously varying the inhibitor concentration and the substrate acetyl-CoA concentration. The activity of acetyltransferase was determined by carrying out the in vitro reactions described above, where the kinetic parameters of one substrate were evaluated at a constant saturating concentration of the other substrate. For GlmU acetyltransferase, another substrate d-glucosamine1-phosphate was added at a fixed concentration of 225 μM. For DapD acetyltransferase, the fixed substrate (2-aminopimelic acid) was used at 5 mM. The Ki and inhibition types of ChryA on GlmU and DapD were determined by Lineweaver-Burk and Dixon's plots created by GraphPad Prism 7.

Isolation and quantitation of peptidoglycan

Isolation and quantification of peptidoglycan in sacculi were performed as described previously with modifications (78). Briefly, 30 ml of S. aureus Newman cells in the logarithmic phase was treated with various concentrations of ChryA, fosfomycin, and ciprofloxacin for 30 min at 37°C. The cells (about 109 CFU) were centrifuged and washed with PBS twice. The pellets were rapidly resuspended in chilled 0.25% SDS solution (0.1 M tris/HCl, pH 6.8) and boiled for 20 min at 100°C in a heating block. After washing at least twice with ddH2O, the pellets were lastly resuspended in 1 ml of ddH2O. The suspension was then supplemented with 500 μl of 0.1 M tris/HCl (pH 6.8) containing deoxyribonuclease I (15 μg/ml; NEB) and ribonuclease (60 μg/ml; NEB), incubated for 60 min at 37°C in a shaker, and then with trypsin (50 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for another 60 min at 37°C. The suspension was boiled for 3 min at 100°C and subjected to ultracentrifugation (5 min at 10,000 rpm). Pellets were washed once with ddH2O and resuspended in 1 M HCl solution to hydrolysis for 6 hours at 37°C. Last, the suspension was centrifuged, washed with ddH2O at least three times, resuspended in 1 ml of ddH2O, and stored at −20°C for further analysis. The peptidoglycan content is expressed in terms of its muramic acid content. The quantification of purified muramic acid from antibiotics-treated S. aureus cells was performed following the standard curve method as described previously (79). The standard curve of muramic acid was made by plotting the amount of muramic acid (in μg) as the X axis and the absorbance value of OD560 as the Y axis.

MST assay

The MST assay was conducted on a NanoTemper Monolith NT.115 instrument (80). The purified wild-type and mutated proteins were labeled with Monolith His-tag Labeling Kit RED-tris-NTA second Generation (Nano Temper, Germany), followed by the manufacturer’s protocol. Subsequently, labeled target proteins were mixed with various concentrations of ChryA in the reaction buffer (PBST) containing 20 mM Hepes (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM fresh dithiothreitol, and 0.05% Tween 20. After incubation for 10 min under room temperature, 10 μl of the mixtures were loaded into premium coated capillaries for measurement. The MST data were analyzed by Nano temper software (1.5.41) to fit the independent experiment data and determine Kd and SD values. The figure was generated by using GraphPad Prism 7 software.

Transmission electron microscope

The effects of ChryA on the cell structure of S. aureus USA300 were examined with a transmission electron microscope. Briefly, S. aureus USA300 cells in the logarithmic phase were treated with 0.5× MIC of ChryA and fosfomycin (MIC = 4 μg/ml) at 37°C in fresh LB medium. DMSO was used as a negative control. Samples were centrifuged at 2000g for 10 min, and bacterial pellets were fixed by resuspending in 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). Bacterial pellets were then embedded in 2% agarose and postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide overnight at room temperature. After washing, samples were dehydrated multiple times in increasing concentrations of ethanol and embedded in Durcupan resin (Sigma-Aldrich). Fifty-five–nanometer sections were examined using a JEM-1200 transmission electron microscope (JEOL; Akishima, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a 4-K Eagle digital camera (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA).

Determination of growth rates

Growth rates of the recombinant chromosomal mutants and the wild-type (Newman) strains were determined in LB broth using a Synergy HTX multimode microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). Three independent cultures of each strain were grown overnight, and the cultures were diluted 1:250 into fresh LB broth with or without ChryA the next day. Cells were incubated at 37°C with shaking for 14 hours, and the OD600 value was measured at 1-hour intervals. The growth rate was calculated by the software Origin 2021. The fastest growth was defined as a slope of a tangent parallel to linear log-phase growth. All exponential growth rates of the mutants were normalized to that calculated for the wild-type strain.

ROS detection

ROS production was detected and quantified using a Cell (GMS10016.13 v. A) ROS Assay kit (Genmed Scientifics, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA), which uses 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA) as a fluorescent probe. Briefly, the S. aureus Newman cells in mid-log-phase were diluted to an OD600 of 0.1, and then, the cultures were incubated with various concentrations of ChryA or antibiotics for 30 min at 37°C. After treatment, aliquots of the GENMED Reagent B were added to test cultures to give a final concentration of 10 μM. Cultures were then incubated at 37°C for another 30 min in the dark, and OD600 and fluorescence (excitation, 490 nm; emission, 515 nm) were then quantified with a Synergy HTX multimode microplate reader. Fluorescence data were normalized against OD600 values to account for differences in bacterial growth between antibiotic concentrations. The detection of ROS production was also measured by fluorescence microscopy. The glass slides were viewed in fluorescein isothiocyanate using a fluorescence microscope (LSM 710; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Membrane permeability assay

The fluorescent probe N-phenyl-1-naphthylamine (NPN; Sigma-Aldrich) was used to evaluate the membrane integrity of S. aureus Newman treated by ChryA or vancomycin. The S. aureus Newman cells in mid-log-phase were diluted to an OD600 of 0.1, and then, the cultures were washed and resuspended with 5 mM Hepes (pH 7.0). The dye NPN was added to a final concentration of 100 μM. After incubation at 37°C for 10 min in the dark, 99 μl of probe-labeled bacterial cells were added to black polystyrene 96-well plates (JET BIOFIL, China). Then, 1 μl of each antibiotic was added to the desired final concentration. After incubation for 10 min, fluorescence was measured on Synergy HTX multimode microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA) with the excitation wavelength at 350 nm and the emission wavelength at 420 nm.

Membrane potential assays

Membrane potential was measured using the potentiometric fluorescent probe DiSC3 (Sigma-Aldrich) (5). S. aureus Newman cells in mid-log-phase were diluted to OD600 of 0.1, resuspended in PBS, and distributed into black polystyrene 96-well plates (JET BIOFIL, China). DiSC3 (5) was added to a final concentration of 1 μM, and the culture was monitored at 37°C for 30 min (excitation, 650 nm; emission, 677 nm) with a Synergy HTX multimode microplate reader (BioTek Instruments). After baseline fluorescence was recorded, a final concentration of 10 mM KCl and the compound were added to the desired final concentration, and measurements were recorded for an additional 1 hour.

DNA damage and nucleoid fragmentation assay

DNA damage and nucleoid fragmentation are significant markers of bacterial cell death. Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) and TUNEL staining in this study were used to evaluate the nucleoid condensation and DNA strand breaks, respectively. Briefly, S. aureus Newman cells in mid-log-phase were diluted to an OD600 of 0.1 in LB medium and then supplemented with antibiotics at various concentrations. After incubation for 1 hour at 37°C, the cultures were washed and resuspended with PBS. The cells were labeled with the One-step TUNEL Apoptosis Assay Kit (Beyotime, China) for 1 hour or Hoechst 33342 (5 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. Last, the glass slides were viewed using a fluorescence microscope (LSM 710; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism was used for statistical analysis. All of the statistical details for each experiment are described in the figure legends. Differences with P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Lan, J. Davies, and H. Xu for providing S. aureus strains.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82073899 and 31570053 to H.B.), the National Key R&D Program of China (no. 2018YFC0311000 to H.B.), and the Jiangsu Specially Appointed Professor and Jiangsu Medical Specialist Programs of China (to H.B.).

Author contributions: H.B. designed research. J.J., M.Zhe., C.Z., and Y.G. performed all bacterial experiments. M.Zhe. and B.L. performed protein purification. M.Zhe., Y.B., Q.T., and L.Zh. performed in vitro activity assays. J.J., M.Zhe., C.Z., B.L., Y.B., X.H., and L.Ze. performed a mouse study. J.J., H.Z., and F.S. extracted ChryA. C.L. and M.Zha. performed MST assays. J.J., M.Zhe., C.Z., and K.H. performed the bioinformatic study and analyzed data. H.B., J.J., M.Zhe., and K.H. wrote the manuscript with support from all the authors. All authors discussed and commented on the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Whole-genome sequencing data are available on the SRA repository under the BioProject number PRJNA873145.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S10

Tables S1 to S4

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.S. Y. Tong, J. S. Davis, E. Eichenberger, T. L. Holland, V. G. Fowler Jr., Staphylococcus aureus infections: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28, 603–661 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.E. Tacconelli, M. Tumbarello, R. Cauda, Staphylococcus aureus infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 339, 2026–2027 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.P. A. Maple, J. M. Hamilton-Miller, W. Brumfitt, World-wide antibiotic resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 1, 537–540 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.A. Shariati, M. Dadashi, Z. Chegini, A. van Belkum, M. Mirzaii, S. S. Khoramrooz, D. Darban-Sarokhalil, The global prevalence of Daptomycin, Tigecycline, Quinupristin/Dalfopristin, and Linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci strains: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 9, 56 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.M. Wali, M. S. Shah, T. U. Rehman, H. Wali, M. Hussain, L. Zaman, F. U. Khan, A. H. Mangi, Detection of linezolid resistance cfr gene among MRSA isolates. J. Infect. Public Health 15, 1142–1146 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.M. Vestergaard, D. Frees, H. Ingmer, Antibiotic resistance and the MRSA problem. Microbiol, Spectr. 7, 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0057-2018, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.T. J. Foster, Antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Current status and future prospects. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 41, 430–449 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.M. Fauvart, V. N. De Groote, J. Michiels, Role of persister cells in chronic infections: Clinical relevance and perspectives on anti-persister therapies. J. Med. Microbiol. 60, 699–709 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.A. Harms, E. Maisonneuve, K. Gerdes, Mechanisms of bacterial persistence during stress and antibiotic exposure. Science 354, aaf4268 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.K. Schilcher, A. R. Horswill, Staphylococcal biofilm development: Structure, regulation, and treatment strategies. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 84, e00026-19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.J. Dai, R. Han, Y. Xu, N. Li, J. Wang, W. Dan, Recent progress of antibacterial natural products: Future antibiotics candidates. Bioorg. Chem. 101, 103922 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.P. Sass, M. Josten, K. Famulla, G. Schiffer, H. G. Sahl, L. Hamoen, H. Brötz-Oesterhelt, Antibiotic acyldepsipeptides activate ClpP peptidase to degrade the cell division protein FtsZ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 17474–17479 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.N. Silber, S. Pan, S. Schäkermann, C. Mayer, H. Brötz-Oesterhelt, P. Sass, Cell division protein FtsZ is unfolded for N-terminal degradation by antibiotic-activated ClpP. MBio 11, e01006-20 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.L. L. Ling, T. Schneider, A. J. Peoples, A. L. Spoering, I. Engels, B. P. Conlon, A. Mueller, T. F. Schäberle, D. E. Hughes, S. Epstein, M. Jones, L. Lazarides, V. A. Steadman, D. R. Cohen, C. R. Felix, K. A. Fetterman, W. P. Millett, A. G. Nitti, A. M. Zullo, C. Chen, K. Lewis, A new antibiotic kills pathogens without detectable resistance. Nature 517, 455–459 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.E. J. Culp, N. Waglechner, W. Wang, A. A. Fiebig-Comyn, Y. P. Hsu, K. Koteva, D. Sychantha, B. K. Coombes, M. S. van Nieuwenhze, Y. V. Brun, G. D. Wright, Evolution-guided discovery of antibiotics that inhibit peptidoglycan remodelling. Nature 578, 582–587 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.M. T. Meenu, G. Kaul, A. Akhir, M. Shukla, K. V. Radhakrishnan, S. Chopra, Developing the natural prenylflavone artocarpin from artocarpus hirsutus as a potential lead targeting pathogenic, multidrug-resistant staphylococcus aureus, persisters and biofilms with no detectable resistance. J. Nat. Prod. 85, 2413–2423 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.M. T. Meenu, G. Kaul, M. Shukla, K. V. Radhakrishnan, S. Chopra, Cudraflavone C from Artocarpus hirsutus as a promising inhibitor of pathogenic, multidrug-resistant s. aureus, persisters, and biofilms: A new insight into a rational explanation of traditional wisdom. J. Nat. Prod. 84, 2700–2708 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.L. van Geelen, F. Kaschani, S. S. Sazzadeh, E. T. Adeniyi, D. Meier, P. Proksch, K. Pfeffer, M. Kaiser, T. R. Ioerger, R. Kalscheuer, Natural brominated phenoxyphenols kill persistent and biofilm-incorporated cells of MRSA and other pathogenic bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 104, 5985–5998 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.F. Strelitz, H. Flon, I. N. Asheshov, Chrysomycin: A new antibiotic substance for bacterial viruses. J. Bacteriol. 69, 280–283 (1955). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.K. Kitamura, Y. Ando, T. Matsumoto, K. Suzuki, Total synthesis of ArylC-glycoside natural products: Strategies and tactics. Chem. Rev. 118, 1495–1598 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.T. T. Wei, K. M. Byrne, D. Warnick-Pickle, M. Greenstein, Studies on the mechanism of actin of gilvocarcin V and chrysomycin A. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 35, 545–548 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.S. I. Wada, R. Sawa, F. Iwanami, M. Nagayoshi, Y. Kubota, K. Iijima, C. Hayashi, Y. Shibuya, M. Hatano, M. Igarashi, M. Kawada, Structures and biological activities of novel 4’-acetylated analogs of chrysomycins A and B. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 70, 1078–1082 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.F. Wu, J. Zhang, F. Song, S. Wang, H. Guo, Q. Wei, H. Dai, X. Chen, X. Xia, X. Liu, L. Zhang, J. Q. Yu, X. Lei, Chrysomycin A derivatives for the treatment of multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis. ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 928–938 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.B. Muralikrishnan, L. K. Edison, A. Dusthackeer, G. R. Jijimole, R. Ramachandran, A. Madhavan, R. A. Kumar, Chrysomycin A inhibits the topoisomerase I of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 75, 226–235 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Z. Xu, S. Zheng, X. Gao, Y. Hong, Y. Cai, Q. Zhang, J. Xiang, D. Xie, F. Song, H. Zhang, H. Wang, X. Sun, Mechanochemical preparation of chrysomycin A self-micelle solid dispersion with improved solubility and enhanced oral bioavailability. J. Nanobiotechnol. 19, 164 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D. N. Liu, M. Liu, S. S. Zhang, Y. F. Shang, F. H. Song, H. W. Zhang, G. H. du, Y. H. Wang, Chrysomycin A inhibits the proliferation, migration and invasion of U251 and U87-MG glioblastoma cells to exert its anti-cancer effects. Molecules 27, 6148 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.M. Liu, S. S. Zhang, D. N. Liu, Y. L. Yang, Y. H. Wang, G.-H. Du, Chrysomycin A attenuates neuroinflammation by down-regulating NLRP3/cleaved caspase-1 signaling pathway in LPS-stimulated mice and BV2 cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 6799 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Y. Q. Li, X. S. Huang, K. Ishida, A. Maier, G. Kelter, Y. Jiang, G. Peschel, K. D. Menzel, M. G. Li, M. L. Wen, L. H. Xu, S. Grabley, H. H. Fiebig, C. L. Jiang, C. Hertweck, I. Sattler, Plasticity in gilvocarcin-type C-glycoside pathways: Discovery and antitumoral evaluation of polycarcin V from Streptomyces polyformus. Org. Biomol. Chem. 6, 3601–3605 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.V. Defraine, M. Fauvart, J. Michiels, Fighting bacterial persistence: Current and emerging anti-persister strategies and therapeutics. Drug Resist. Updat. 38, 12–26 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.P. J. Johnson, B. R. Levin, Pharmacodynamics, population dynamics, and the evolution of persistence in Staphylococcus aureus. PLOS Genet. 9, e1003123 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.E. M. Waters, S. E. Rowe, J. P. O'Gara, B. P. Conlon, Convergence of staphylococcus aureus persister and biofilm research: Can biofilms be defined as communities of adherent persister cells? PLOS Pathog. 12, e1006012 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.R. Pati, R. K. Mehta, S. Mohanty, A. Padhi, M. Sengupta, B. Vaseeharan, C. Goswami, A. Sonawane, Topical application of zinc oxide nanoparticles reduces bacterial skin infection in mice and exhibits antibacterial activity by inducing oxidative stress response and cell membrane disintegration in macrophages. Nanomedicine 10, 1195–1208 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.C. A. Hutton, T. J. Southwood, J. J. Turner, Inhibitors of lysine biosynthesis as antibacterial agents. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 3, 115–127 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.C. E. Deutch, L-Proline nutrition and catabolism in Staphylococcus saprophyticus. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 99, 781–793 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.J. van Heijenoort, Recent advances in the formation of the bacterial peptidoglycan monomer unit. Nat. Prod. Rep. 18, 503–519 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.M. Aboshkiwa, B. al-Ani, G. Coleman, G. Rowland, Cloning and physical mapping of the Staphylococcus aureus rplL, rpoB and rpoC genes, encoding ribosomal protein L7/L12 and RNA polymerase subunits beta and beta. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138, 1875–1880 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Y. Ji, A. Marra, M. Rosenberg, G. Woodnutt, Regulated antisense RNA eliminates alpha-toxin virulence in Staphylococcus aureus infection. J. Bacteriol. 181, 6585–6590 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.R. A. Forsyth, R. J. Haselbeck, K. L. Ohlsen, R. T. Yamamoto, H. Xu, J. D. Trawick, D. Wall, L. Wang, V. Brown-Driver, J. M. Froelich, K. G. C., P. King, M. McCarthy, C. Malone, B. Misiner, D. Robbins, Z. Tan, Z. Y. Zhu, G. Carr, D. A. Mosca, C. Zamudio, J. G. Foulkes, J. W. Zyskind, A genome-wide strategy for the identification of essential genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 1387–1400 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.K. L. Blake, A. J. O'Neill, D. Mengin-Lecreulx, P. J. F. Henderson, J. M. Bostock, C. J. Dunsmore, K. J. Simmons, C. W. G. Fishwick, J. A. Leeds, I. Chopra, The nature of Staphylococcus aureus MurA and MurZ and approaches for detection of peptidoglycan biosynthesis inhibitors. Mol. Microbiol. 72, 335–343 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.K. E. DeMeester, H. Liang, M. R. Jensen, Z. S. Jones, E. A. D’Ambrosio, S. L. Scinto, J. Zhou, C. L. Grimes, Synthesis of functionalized N-acetyl muramic acids to probe bacterial cell wall recycling and biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 9458–9465 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.F. M. Kahan, J. S. Kahan, P. J. Cassidy, H. Kropp, The mechanism of action of fosfomycin (phosphonomycin). Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 235, 364–386 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.M. E. Falagas, E. K. Vouloumanou, G. Samonis, K. Z. Vardakas, Fosfomycin. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 29, 321–347 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.J. T. Cheng, J. D. Hale, M. Elliot, R. E. Hancock, S. K. Straus, Effect of membrane composition on antimicrobial peptides aurein 2.2 and 2.3 from Australian southern bell frogs. Biophys. J. 96, 552–565 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.H. Yonezawa, K. Okamoto, K. Tomokiyo, N. Izumiya, Mode of antibacterial action by gramicidin S. J. Biochem. 100, 1253–1259 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.J. L. Dombach, J. L. J. Quintana, C. S. Detweiler, Staphylococcal bacterial persister cells, biofilms, and intracellular infection are disrupted by JD1, a membrane-damaging small molecule. MBio 12, e0180121 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.J. H. Yu, X. F. Xu, W. Hou, Y. Meng, M. Y. Huang, J. Lin, W. M. Chen, Synthetic cajaninstilbene acid derivatives eradicate methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus persisters and biofilms. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 224, 113691 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.C. H. Lu, C. W. Shiau, Y. C. Chang, H. N. Kung, J. C. Wu, C. H. Lim, H. H. Yeo, H. C. Chang, H. S. Chien, S. H. Huang, W. K. Hung, J. R. Wei, H. C. Chiu, SC5005 dissipates the membrane potential to kill Staphylococcus aureus persisters without detectable resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 76, 2049–2056 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.B. Casciaro, M. R. Loffredo, F. Cappiello, G. Fabiano, L. Torrini, M. L. Mangoni, The antimicrobial peptide temporin G: Anti-biofilm, anti-persister activities, and potentiator effect of tobramycin efficacy against Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 9410 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.N. Yang, D. Teng, R. Mao, Y. Hao, X. Wang, Z. Wang, X. Wang, J. Wang, A recombinant fungal defensin-like peptide-P2 combats multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and biofilms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 103, 5193–5213 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.P. Le, E. Kunold, R. Macsics, K. Rox, M. C. Jennings, I. Ugur, M. Reinecke, D. Chaves-Moreno, M. W. Hackl, C. Fetzer, F. A. M. Mandl, J. Lehmann, V. S. Korotkov, S. M. Hacker, B. Kuster, I. Antes, D. H. Pieper, M. Rohde, W. M. Wuest, E. Medina, S. A. Sieber, Repurposing human kinase inhibitors to create an antibiotic active against drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, persisters and biofilms. Nat. Chem. 12, 145–158 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.A. T. Dharmaraja, Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in therapeutics and drug resistance in cancer and bacteria. J. Med. Chem. 60, 3221–3240 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.M. A. Kohanski, D. J. Dwyer, B. Hayete, C. A. Lawrence, J. J. Collins, A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell 130, 797–810 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.H. van Acker, T. Coenye, The role of reactive oxygen species in antibiotic-mediated killing of bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 25, 456–466 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.I. Keren, Y. Wu, J. Inocencio, L. R. Mulcahy, K. Lewis, Killing by bactericidal antibiotics does not depend on reactive oxygen species. Science 339, 1213–1216 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]