Abstract

Irreversible aggregation of misfolded proteins is the underlying molecular cause of numerous pathologies, including diabetes type 2, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s diseases. Such an abrupt protein aggregation results in the formation of small oligomers that can propagate into amyloid fibrils. A growing body of evidence suggests that protein aggregation can be uniquely altered by lipids. However, the role of the protein-to-lipid (P:L) ratio on the rate of protein aggregation, as well as the structure and toxicity of corresponding protein aggregates remains poorly understood. In this study, we investigate the role of the P:L ratio of five different phospho- and sphingolipids on the rate of lysozyme aggregation. We observed significantly different rates of lysozyme aggregation at 1:1, 1:5, and 1:10 P:L ratios of all analyzed lipids except phosphatidylcholine (PC). However, we found that at those P:L ratios, structurally and morphologically similar fibrils were formed. As a result, for all studies of lipids except PC, mature lysozyme aggregates exerted insignificantly different cell toxicity. These results demonstrate that the P:L ratio directly determines the rate of protein aggregation, however, has very little if any effect on the secondary structure of mature lysozyme aggregates. Furthermore, our results point to the lack of a direct relationship between the rate of protein aggregation, secondary structure, and toxicity of mature fibrils.

Keywords: Amyloid, Lysozyme, Phospholipids, Toxicity, ROS

1. Introduction

Abrupt aggregation of misfolded proteins is the hallmark of numerous pathologies including diabetes type 2, Parkinson, Alzheimer, and Huntington’s diseases [1–3]. This process yields highly heterogeneous protein oligomers that can propagate into fibrils, long unbranched β-sheet-rich structures that exert similar to the oligomers cell toxicity [1,2,4–6]. The utilization of cryo-electron (cryo-EM) microscopy and solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (ss-NMR) helped to reveal the secondary structure of amyloid fibrils [7–9]. It has been found that fibrils were composed of several filaments that had cross-β-sheet secondary structure [7–12]. These filaments could coil and associate side-by-side forming twisted and tape-like fibril polymorphs [13,14]. However, the high structural and morphological heterogeneity of amyloid oligomers, as well as their transient nature, limit the use of cryo-EM and ss-NMR for elucidation of their secondary structure. Recently, our group and other research groups demonstrated that this limitation could be overcome by optical nanoscopy techniques, such as atomic force microscopy Infrared (AFM-IR) spectroscopy [15–20]. Using AFM-IR, Zhou and Kurouski found several structurally different oligomers formed by α-synuclein (α-Syn), a protein that is directly linked to the onset and progression of Parkinson’s disease, at the early, middle, and late stages of protein aggregation [16]. Some of the early-stage oligomers were dominated by parallel-β-sheet, whereas others had a substantial amount of anti-parallel-β-sheet and unordered protein secondary structure. However, α-Syn aggregates observed at the late stages possessed exclusively parallel-β-sheet, which suggested the interconversion of anti-parallel into parallel-β-sheet upon preparation of the oligomers into fibrils. Using AFM-IR, Rizevsky and co-workers investigated the secondary structure of insulin oligomers formed in the presence of two phospholipids: phosphatidylcholine (PC) and cardiolipin (CL) [21]. It was found that both PC and CL could uniquely alter the secondary structure of insulin oligomers. Furthermore, these lipids were found in the structure of insulin oligomers grown in their presence [21]. Furthermore, Matveyenka and co-workers discovered that lipids not only modified the secondary structure of protein oligomers but also uniquely altered the rate of insulin aggregation [5,6,22–25].

Experimental results reported by Galvagnion and co-workers showed that the rate of α-Syn could be uniquely altered by the protein-to-lipid (P:L) ratio [26–28]. It was found that the presence of large uniflagellar vesicles (LUVs) at low concentrations relative to the concentration of α-Syn increased the rate of protein aggregation. However, with an increase in the concentration of LUVs relative to the concentration of the protein, Galvagnion and co-workers observed a decrease in the rate of α-Syn aggregation [26–28]. This observation suggested that lipid membranes facilitated an assembly of amyloid-associated proteins. However, with the increase in the membrane surface, the probability of protein-protein interaction decreased, which resulted in the discussed decreased rate of protein aggregation. The question to ask is whether the observed by Galvagnion and co-workers effect of the P:L ratio was significant only for α-Syn aggregation or whether the concentration of lipids could also modify the aggregation rate of other proteins.

In the current study, we investigate the extent to which different P:L ratios could alter the rate of lysozyme aggregation. This small, 14.3 kDa protein can easily aggregate at low pH and elevated temperatures that facilitate protein misfolding [6,29]. Utilization of deep UV resonance Raman spectroscopy revealed that lysozyme misfolding was primarily triggered by denaturation of α-helical domains of the protein with their subsequent assembly into a cross-β-sheet secondary structure [30–34]. Furthermore, Kurouski and co-workers showed that pH directly determines the associated mechanisms of cross-β-sheet filaments of lysozyme [35]. It was found that at pH below 2, lysozyme yielded tape-like fibrils, whereas, at pH above this point, a left-twisted fibril polymorph was formed. Expanding upon this, we determined the rate of lysozyme aggregation in the presence of 1:1, 1:5 and 1:10 P:L ratios of PC, CL, phosphatidylserine (PS), ceramide (CER), sphingomyelin (SM), as well as a mixture of CL and PC at 1:4 M ratios. PC is a zwitterion that constitutes around 30 % of the plasma and organelle membranes [36–38]. CL and PS are negatively charged lipids. CL is uniquely localized in the inner mitochondrial membrane where it plays an important role in cell respiration and energy conversion [39]. PS is primarily localized on the cytosolic side of the plasma membrane via ATP-dependent transport [40]. Upon ATP deficiency, PS appears on the exterior part of the membrane, where it is recognized by macrophages that initiate cell apoptosis [37,41,42]. CER and SM occupy around 6 % and 4 % of the plasma membrane, respectively. These lipids form a myelin sheath that surrounds nerve cell axons where they perform an important role in signal transduction [37,41,42]. In this study, we also utilized a set of microscopic and spectroscopic techniques to unravel the secondary structure and morphology of lysozyme aggregates formed at three different P:L ratios. Finally, we employed a set of cell toxicity assays to determine the extent to which such protein:lipid aggregates exerted cell toxicity.

2. Results

2.1. Kinetics of lysozyme aggregation

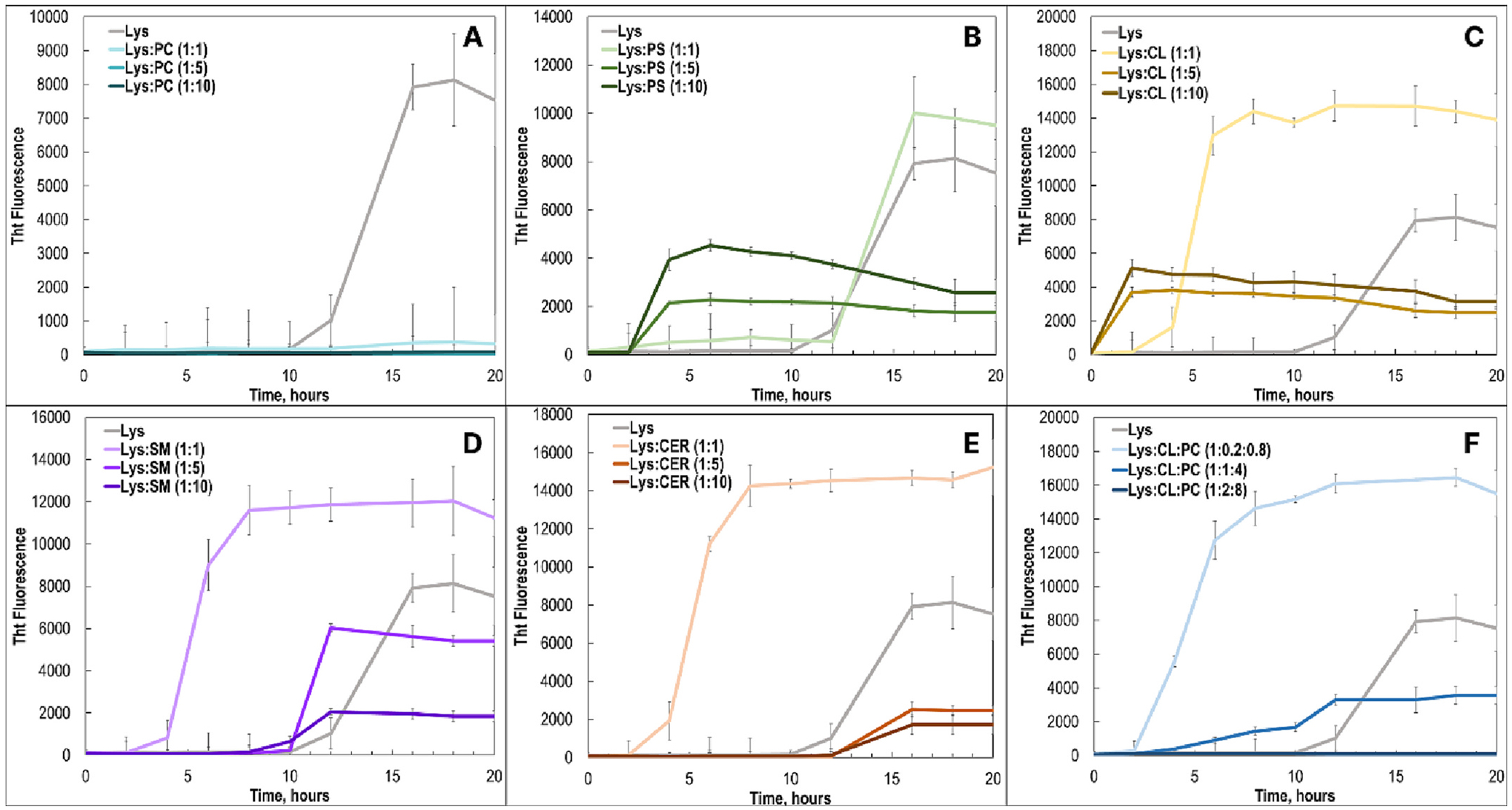

In the lipid-free environment, lysozyme aggregation had a well-defined lag phase that is characterized by an accumulation of oligomeric species [29]. Once their critical concentration was reached (~12 h), protein oligomers rapidly propagate into fibrils, which resulted in an increase in the ThT signal, Fig. 1. We found that in the presence 1:1 P:L ratio of PC, fibril formation was completely inhibited. These results are in a good agreement with the previously reported findings by Zhaliazka and co-workers [29]. Similar results were obtained for higher concentrations of PC relative to the concertation of lysozyme (1:5 and 1:10 P:L). These findings showed that PC strongly inhibits lysozyme fibrillization.

Fig. 1.

Lysozyme exhibits different rates of aggregation in the presence of phospho- and sphingolipids at 1:1, 1:5 and 1:10 M ratios. ThT aggregation kinetics of lysozyme with PC (A), PS (B), CL (C), SM (D), CER (E), and CL:PC (1:4) lipid mixture at 1:1, 1:5 and 1:10 P:L ratios.

Kinetic measurements revealed that equimolar concentration of PS did not significantly alter the aggregation rate of lysozyme. However, with an increase in the concentration of this lipid (1:5 and 1:10 P:L) a drastic increase in the rate of protein aggregation was observed. Specifically, at both 1:5 and 1:10 P:L, we found a significant increase in the ThT intensity at 4 h after the initiation of lysozyme aggregation. Furthermore, for all time points, we observed a stronger signal of ThT for 1:10 P:L at the early stage (4–12 h) compared to those observed for 1:5 and 1:1. However, both 1:5 and 1:10 P:L PS exhibited relatively weaker ThT intensity at the late stages of protein aggregation (12–18 h) compared to 1:1 PS and lysozyme itself. These results demonstrated that a high concentration (1:10 P:L) of PS LUVs strongly accelerated protein aggregation but yielded fewer ThT active aggregates compared to those formed at low concentrations (1:1 P:L) of PS LUVs and in the lipid-free environment.

An even more pronounced effect of different concentrations of LUVs on the rate of lysozyme aggregation was observed for CL. We found that at a 1:1 P:L ratio, CL strongly accelerated protein aggregation compared to the lipid-free conditions. Kinetic measurements revealed an even greater acceleration of lysozyme aggregation at CL 1:5 and 1:10 P:L ratios. However, same as in the case of PS, 1:1 L:P of CL yielded a more intense ThT signal at the late stages of protein aggregation compared to the intensity of the ThT signal for 1:5 and 1:10 L:P. Thus, we could conclude that high concentrations of CL LUVs strongly accelerated lysozyme aggregation, but ultimately yielded fewer ThT active aggregates compared to those formed at 1:1 P:L. It should be noted that a quick flocculation of vesicles could results in overall smaller ThT signals for Lys:PS and Lys:CL aggregation kinetics that had a shortened lag phase.

The same conclusion about the L:P ratios could be made about lysozyme aggregation in the presence of SM and CER. We observed stronger ThT intensity for lysozyme aggregates formed at 1:1 ratio of SM and CER, compared to those grown at 1:5 and 1:10. However, in the case of both SM and CER, we found that low P:L resulted in the strongest acceleration of protein aggregation compared to those observed for 1:5 and 1:10. It should be noted that we did not observed any significant changes in the rate of lysozyme aggregation at 1:5 and 1:10 SM and CER compared to the rate of protein aggregation in the lipid-free environment. Finally, we found that lysozyme aggregation in the presence of a 1:4 lipid mixture of CL:PC at 1:1 P:L ratio results in the strong acceleration of protein aggregation. However, the enhancement rate decreased with an increase in the P:L ratio. Specifically, we found that CL:PC at 1:5 P:L slower accelerates the rate of lysozyme aggregation, whereas presence of CL:PC at 1:10 P:L fully inhibits protein aggregation. As was discussed above, since PC exhibited strong inhibitory effect on lysozyme aggregation. Therefore, it would be expected to observe a deceleration of protein aggregation with an increase in the total concentration of PC in the solution for PC:CL mixture. It should be noted that ThT affinity to amyloid aggregates, which ultimately correlates with the intensity of ThT fluorescence can be affected by hydrophobic/hydrophilic properties of such aggregates. Therefore, discussed above difference in the ThT intensity of different protein samples cannot be unambiguously used for quantification of the concentration of amyloid aggregates.

2.2. Morphological analysis of lysozyme aggregates

AFM analysis of lysozyme aggregates grown in the lipid-free environment revealed presence of fibril species that had 20–30 nm in height, as well as small protein oligomers that had 6–8 nm in diameter, Fig. 2. We considered aggregates to be ‘oligomers’ in the case of their spherical topology, whereas protein aggregates that have uneven length and width dimensions were classified as ‘fibrils’. Morphologically similar oligomers were observed for Lys:PC at all three P:L ratios. However, in addition to the oligomers, visual examination of AFM images revealed the presence of short fibril-like species that had 80–100 nm in length. Visual examination of AFM images also revealed that Lys:PS 1:1 and 1:5 P:L contained a substantially greater amount of these short fibrils and lower amount of protein oligomers compared to Lys:PC samples. However, nearly equal amount of oligomers and fibrils was observed for 1:10 P:L of Lys:PS. AFM imaging showed that all analyzed Lys:CL samples had a mixture of oligomers and fibrils. The same conclusion could be made about Lys:SM. However, Lys:SM fibrils were substantially thinner than corresponding fibrils of Lys:CER. Nevertheless, we observed no significant variability in the morphology between different P:L ratios of both Lys:SM and Lys:CER. AFM imaging showed that presence of PC:CL LUVs at 1:1 and 1:5 P:L ratios yielded fibril species with a large distribution of lengths. However, predominantly long fibrils were observed for 1:10 P:L of PC:CL mixture. These results of visual examination of AFM images reported in Fig. 2 show that lipids themselves uniquely alter morphology of lysozyme aggregates. These results are consistent with our previous findings [6,29]. However, very little if any differences were found for different P:L ratios of the same lipid. Thus, differences in the lipid concentration relative to the concentration of the protein do not significantly alter the morphology of the corresponding protein aggregates.

Fig. 2.

Microscopic analysis of lysozyme aggregates grown with different phospho- and sphingolipids at 1:1, 1:5 and 1:10 P:L ratios. AFM images of lysozyme fibrils formed in the lipid-free environment (Lys, Lys:PC, Lys:PS, Lys:CL, Lys:SM, Lys:CER, and Lys:PC:CL at 1:1 (left column), 1:5 (middle column) and 1:10 (right column) P:L ratios.

2.3. Structural characterization of protein aggregates

We utilized ATR-FTIR to investigate the secondary structure of lysozyme aggregates grown at different P:L ratios, as well as fibrils formed in the lipid-free environment. ATR-FTIR spectrum acquired from lysozyme fibrils grown in the lipid-free environment (Lys) exhibited both amide I (1620–1700 cm−1) and amide II (1500–1550 cm−1) bonds, Fig. 3 [6,43]. Specifically, amide I band had maximum at ~1628 cm−1 with a small shoulder at ~1660 cm−1, which indicated the predominance of parallel β-sheet with some unordered protein secondary structure present in these fibrils [44,45]. ATR-FTIR showed that the secondary structure of all Lys:PC aggregates was dominated by unordered protein secondary structure, which is consistent with the previously reported findings. It should be noted that we did not observe any changes in the position of amide I between 1:1, 1:5 and 1:10 P:L of Lys: PC. Based on these results, we can conclude that L:P ratio has very little if any effect on the secondary structure of protein aggregates formed in the presence of PC. The same conclusions could be made about lysozyme fibrils grown in the presence of PS and CL. Although Lys:PS and Lys:CL samples were dominated by parallel β-sheet (amide I band has maximum at ~1628 cm−1), we did not find substantial differences between the secondary structure of 1:1, 1:5 and 1:10 P:L Lys:PS or Lys:CL aggregates. It should be noted that IR spectra of both 1:5 and 1:10 Lys:PC, Lys:PS and Lys:CL exhibited a vibration ~1725 cm−1, which originated from the carbonyl vibration of the lipids [6,21]. This band was observed neither for Lys:PC and Lys:PS nor for Lys:CL formed at 1:1 L:P ratio. These results demonstrate substantially greater amount of lipids present in the protein samples grown in the presence of 1:5 and 1:10 P:L ratios of lipids.

Fig. 3.

Secondary structure of lysozyme aggregates grown with different phospho- and sphingolipids at 1:1, 1:5 and 1:10 P:L ratios. IR spectra of lysozyme fibrils formed in the presence of PC (A), PS (B), CL (C), SM (D), CER (E), and CL:PC (1:4) lipid mixture at 1:1, 1:5 and 1:10 P:L ratios.

AFM-IR analysis of Lys:SM, Lys:CER and Lys:PC:CL demonstrated that secondary structure of these aggregates directly depends on the P:L ratio at which these species were formed. Specifically, we found that 1:1P:L Lys:SM was dominated by parallel β-sheet (amide I band has maximum at ~1628 cm−1), whereas protein aggregates grown in both 1:5 and 1:10 P:L of SM had predominately unordered protein secondary structure. Even greater degree of structural heterogeneity was observed for Lys:CER samples. Specifically, amide I was found to be right-shifted for 1:1 P:L and left-shifted for 1:5 P:L of SM relative to the amide I band position in the spectra of lysozyme fibrils grown in the lipid-free environment. Finally, the position of the amide I band in the IR spectra acquired from 1:10 P:L of Lys:CER had a distinctly different maximum compared to amide I in the spectra acquired from both 1:1 and 1:5 P:L of Lys:CER. These findings demonstrate that the secondary structure of Lys: CER aggregates grown at different P:L ratios was slightly different. Thus, our findings show that concentration of CER relative to the concentration of lysozyme plays a critically important role in determining the secondary structure of corresponding protein aggregates. The same conclusions could be made about Lys:PC:CL aggregates. Specifically, we found that the amide I band was slightly right-shifted in the IR spectra acquired from Lys:PC:CL aggregates grown at 1:1 P:L ratio compared to the position of this vibration in the IR spectra acquired from lysozyme fibrils grown in the lipid-free environment. IR spectrum acquired from Lys:PC:CL aggregates grown at 1:5 P:L demonstrated the presence of a significantly greater amount of unordered proteins in these aggregates compared to those grown at a 1:1 P:L ratio. Finally, Lys:PC:CL aggregates grown at 1:10 P:L were fully dominated by unordered protein secondary structure. Thus, these results demonstrate that the P:L ratio strongly alters the secondary structure of Lys:PC:CL aggregates.

2.4. Toxicity of lysozyme aggregates

We utilize mice midbrain N27 cell line and a set of toxicity assays to examine the extent to which the P:L ratio could alter the toxicity of lysozyme aggregates grown in the presence of lipids and lipid mixtures. For this, we utilized the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay [5,22]. Amyloid aggregates exert toxicities by enhancing ROS production and inducing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells [4,5,22,46]. Therefore, we examined the extent to which these structures are engaged in ROS production and mitochondrial dysfunction of cells, Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Lysozyme aggregates grown in the presence of different P:L ratios exert similar cell toxicity. Histograms of LDH (top), JC-1 (middle) and ROS (bottom) toxicity assays of Lys, Lys:PC, Lys:PS, Lys:CL, Lys:SM, Lys:CER and Lys:CL:PC grown at 1:1 (blue sapphire), 1:5 (blue crayola), 1:10 (sky blue), lysozyme aggregates grown in the lipid-free environment (marine blue), as well as control (grey).

After 24 h of incubation of lysozyme (400 μM) with and without lipids at 65 °C, sample triplicates were exposed to mice midbrain N27 cells for 48 h. For each of the presented results, three independent measurements were made. Red asterisks (*) show the statistical significance of Lys:PC, Lys:PS, Lys:CL, Lys:SM, Lys:CER and Lys: CL:PC samples compared to Lys. Blue asterisks show statistical significance between different P:L ratios. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001; NS is non-significant difference.

LHD results show that all lysozyme aggregates that were grown in the presence of lipids, except Lys:PC 1:10, Lys:PC:CL 1:5 and 1:10 exerted significantly lower cell toxicity compared to the fibrils formed in the lipid-free environment. However, protein aggregates grown at different P:L ratios except PC exerted the same levels of cell toxicity. We found that only Lys:PC 1:1 P:L exerted significantly lower cell toxicity than corresponding 1:5 aggregates. Finally, we found that Lys:PC 1:10 exerted significantly higher cell toxicity than Lys:PC 1:1 and 1:5 P:L. The same conclusions could be made from the analysis of the levels of mitochondrial dysfunction exerted by these aggregates. However, in this case, we did not observe significant differences between the JC-1 intensity associated with different P:L ratios of Lys:PC aggregates. It should be noted that in this study we compare toxicities of protein aggregates that were formed after 24 h of protein aggregation. As was demosntrated by our previous study, the toxicity primarily originates from the aggretates’ intake by endosomes [25]. One may expect that presence of lipds on their surface can alter the endocytosis properties of such aggregates, and, consequently, the discussed above cell toxicity.

ROS analysis did not reveal significant differences in the ROS levels of these Lys:PC aggregates. The same conclusion could be made about Lys:CL, Lys:CER and Lys:CL:PC samples were grown at different P:L ratios. However, we found significant differences in the exerted ROS levels between Lys:PS fibrils formed at P:L 1:10 and both Lys:PS aggregates grwon at 1:1 and 1:5 P:L ratios. It should be noted that statistically significant differences were observed between Lys:SM 1:5 and 1:10 P:L aggregates. Finally, it should be noted that lipids themselves exerted significantly lower levels of LHD, ROS and JC-1 than the corresponding protein:lipid aggregates, Fig. S1.

3. Discussion

Microscopic examination of amyloid deposits in the midbrain of patients diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease revealed the presence of fragments of lipid-rich membranes, organelles and vesicles [47,48]. This observation suggested that lipids can be involved in the process of abrupt aggregation of α-Syn. Galvagnion and co-workers demonstrate that lipids could uniquely alter the rate of α-Syn aggregation [28,49,50]. Furthermore, this effect could be modulated by the P:L ratio. Experimental findings reported by Zhu and Fink showed that α-Syn aggregation at 1:1 and 1:5 P:L ratio yields aggregates were significantly different secondary structures [51].

Previously reported results by our group showed that lipids uniquely modified insulin and lysozyme aggregation rates, as well as altered the secondary structure of both oligomers and mature fibrils formed by these two proteins in their equimolar presence [5,6,15,22–25]. We also showed that not only the chemical structure and possessed net charge of lipids determine the rate of protein aggregation, but also the degree of unsaturation of fatty acids (FAs) in the phospholipids [22,23]. Specifically, phosphatidic acid and PS with unsaturated FAs exhibited greater enhancement of insulin aggregation compared to their saturated analogs [22,23]. It was also found that protein aggregates grown in the presence of lipids with saturated FAs exerted significantly lower cell toxicity compared to those formed in the presence of lipids with unsaturated FAs [5,6,15,22–25].

Our current findings showed that the P:L ratio of phospholipids and sphingolipids, as well as a mixture of lipids, determined the rate of lysozyme aggregation. However, this effect was not observed for PC, which strongly inhibited lysozyme aggregation at all analyzed P:L ratios. Our results also showed that protein aggregates that were formed at different P:L ratios had substantial structural differences. Nevertheless, these aggregates exert very similar levels of cell toxicity. Matveyenka and co-workers and Zhaliazka and co-workers utilized AFM-IR to examine the secondary structure of individual protein aggregates that were grown in the presence of phospho- and sphingolipids [6,29]. Furthermore, it was found that such aggregates possessed lipids in their structure [6,29]. Our previous studies demonstrated that lipids possessed by such aggregates determine the toxicity that such protein: lipid aggregates exert on cells [6,29]. Recently, Zhaliazka and co-workers also used AFM-IR to investigate lysozyme aggregates grown in the presence of PS at 1:1, 1:5 and 1:10 P:L ratios [29]. It was found that with an increase in the concentration of lipid in the sample, an increase in the amount of lipid in the structure of individual protein aggregates was observed. Specifically, lysozyme fibrils were grown in the presence of 1:10 Lys:PS possessed significantly greater amount of PS compared to the aggregates formed in the presence of both 1:1 and 1:5 Lys:PS. Based on these findings, as well as our current results, one can expect that lipids themselves rather than the amount of lipids determine the level of toxicity that such protein:lipid aggregates exert to cells. Thus, changes in the rate of protein aggregation, as well as the secondary structure of lysozyme fibrils does not play an important role in determining the toxicity of oligomers and fibrils, as the lipids present on the surface of such protein aggregates.

4. Conclusions

Our results show that the P:L ratio of all analyzed phospho and sphingolipids except PC uniquely altered the rate of lysozyme aggregation. We found that at all analyzed P:L ratios, PC strongly inhibited protein aggregation. We also found that protein aggregates formed at 1:1, 1:5 and 1:10 P:L ratios had very similar topologies, whereas some differences in their secondary structure were observed. It was also found that such aggregates possessed lipids in their structure that could uniquely alter the toxicity of lysozyme oligomers and fibrils. However, lysozyme aggregates grown at 1:1, 1:5 and 1:10 P:L ratios exerted very similar cell toxicity to mice midbrain N27 cell line. These findings showed that the presence of lipids rather the amount of lipids on such aggregates or small differences in their secondary structures determine toxicity of lysozyme aggregates grown in the presence of phospho and sphingolipids.

5. Experimental section

5.1. Materials

Hen egg-white lysozyme was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), 1,2-Dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC or PC), 1,2-ditetradecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (DMPS or PS), 1’,3’-bis[1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho]-glycerol (18:0 cardiolipin (CL)), sphingomyelin (SM) and ceramide (CER) were purchased from Avanti (Alabaster, AL, USA).

5.2. Liposome preparation

large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) were prepared from DMPS, DMPC, and CL accordingly to the previously reported assay. Briefly, 0.6 mg of the lipid was dissolved in 2.6 ml of phosphate buffer saline (PBS) pH 7.4. The suspension of lipids was heated for ~30 min in a water bath to ~50 °C. Next, the vial was placed into liquid nitrogen for 3–5 min. This procedure was repeated 10 times. After this, LUV solutions were passed 15 times through a 100 nm membrane using an extruder (Avanti, Alabaster, AL, USA). LUV sizes were determined by dynamic light scattering. Due to the poor assembly properties, no LUVs for SM and CER were prepared; lipids were used as received.

5.3. Hen egg-white lysozyme aggregation

After hen egg-white lysozyme (400 μM) was fully dissolved in PBS, solution pH was adjusted to pH 3.0 using concentrated HCl. For Lys:CL, Lys:CER, Lys:PS, Lys:SM and Lys:PC:CL, 400 μM of lysozyme was mixed with an equivalent concentration of the corresponding lipid to reach 1:1, 1:5 and 1:10 P:L ratios; solution pH was adjusted to pH 3.0 using concentrated HCl. Samples were mixed with thioflavin T (ThT) solution to obtain a final concentration of n 30 μM of ThT. After that, samples were pipetted into a microplate, that was placed in a plate shaker and kept for 24 h at 65 °C with agitation 900 rpm.

5.4. Kinetic measurements

Protein aggregation was monitored using ThT fluorescence assay. For this, protein samples were placed in the plate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). Fluorescence emission was collected at 488 nm with 450 nm excitation. All measurements were made in triplicates.

5.5. AFM imaging

AFM imaging was performed on AIST-NT-HORIBA system (Edison, NJ) equipped with silicon AFM probes (2.7 N/m, 50–80 kHz) that were purchased from Appnano (Mountain View, CA, USA). For each measurement, an aliquot of the sample was diluted with PBS, pH 3.0, deposited on the pre-cleaned silicon wafer, and then dried under a flow of dry nitrogen. Exposition of the fibril suspension varied from several seconds to minutes to reach high concentration of the aggregates on the sample surface. Therefore, density of protein aggregates does not represent their concentration in the solution. Analysis of collected images was done with AIST-NT software (Edison, NJ, USA).

5.6. Attenuated total reflectance Fourier-transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy

For each measurement, protein samples were placed onto ATR crystal and dried at room temperature. Spectra were measured using Spectrum 100 FTIR spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Three spectra were collected from each sample.

5.7. Cell toxicity assays

Mice midbrain N27 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in 96 well-plate (5000 cells per well) at 37 °C under 5 % CO2. Cell media contained 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). After cells reached ~70 % confluency, 100 μL of the cell culture was replaced with 100 μL RPMI 1640 Medium that contained 5 % FBS. Next, protein samples were added to the cells. After 48 h of incubation, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay was performed on the cell medium using CytoTox 96 non-radioactive cytotoxicity assay.

(G1781, Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Absorption measurements were collected at 490 nm using a plate reader (Tecan). Every well was measured 25 times in different locations. All measurements were made in triplicates. t-test was used to determine the significant levels of differences between the toxicity of analyzed samples. In parallel, N27 cells were used for the reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay. For this, ROS reagent (C10422, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) was added to reach the final concentration of 5 μM; cells were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C under 5 % CO2. After the supernatant was removed, cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in 200 μL of PBS in the flow cytometry tubes. Sample measurements were made in LSR II Flow Cytometer (BD, San Jose, CA, USA) using a red channel (λ = 633 nm). Percentages of ROS cells were determined using LSR II software. For JC-1 staining, 1 μL of JC-1 reagent (M34152A, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) was added to cells and incubated at 37 °C under 5 % CO2 for 30 min. After the supernatant was removed, cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in 200 μL of PBS in the flow cytometry tubes. Sample measurements were made in LSR II Flow Cytometer (BD, San Jose, CA, USA) using a red channel (λ = 633 nm). JC-1 intensity was determined using LSR II software. All measurements were made in triplicates. t-test was used to determine the significant level of differences between toxicity of analyzed samples.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the National Institute of Health for the provided financial support (R35GM142869).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Dmitry Kurouski reports financial support was provided by Texas A&M University.

Abbreviations:

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PS

phosphatidylserine

- CER

ceramide

- SM

sphingomyelin

- CL

cardiolipin

- LUVs

large unilamellar vesicles

- Lys

lysozyme

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- ThT

thioflavin T

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2023.159305.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

K.Z. performed kinetics and FTIR experiments, analyzed data, V.S. and S.R. performed AFM experiments, analyzed data, M.M. performed toxicity experiments, analyzed data, S.R. D.K. designed the project, analyzed data. All authors wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- [1].Chiti F, Dobson CM, Protein misfolding, amyloid formation, and human disease: a summary of Progress over the last decade, Annu. Rev. Biochem 86 (2017) 27–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Knowles TP, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM, The amyloid state and its association with protein misfolding diseases, Nat. Rev 15 (2014) 384–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Iadanza MG, Jackson MP, Hewitt EW, Ranson NA, Radford SE, A new era for understanding amyloid structures and disease, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 19 (2018) 755–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chen SW, Drakulic S, Deas E, Ouberai M, Aprile FA, Arranz R, Ness S, Roodveldt C, Guilliams T, De-Genst EJ, Klenerman D, Wood NW, Knowles TP, Alfonso C, Rivas G, Abramov AY, Valpuesta JM, Dobson CM, Cremades N, Structural characterization of toxic oligomers that are kinetically trapped during alpha-synuclein fibril formation, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112 (2015) E1994–E2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Matveyenka M, Rizevsky S, Kurouski D, The degree of unsaturation of fatty acids in phosphatidylserine alters the rate of insulin aggregation and the structure and toxicity of amyloid aggregates, FEBS Lett 596 (2022) 1424–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Matveyenka M, Zhaliazka K, Rizevsky S, Kurouski D, Lipids uniquely alter secondary structure and toxicity of lysozyme aggregates, FASEB J 36 (2022), e22543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Li B, Ge P, Murray KA, Sheth P, Zhang M, Nair G, Sawaya MR, Shin WS, Boyer DR, Ye S, Eisenberg DS, Zhou ZH, Jiang L, Cryo-EM of full-length alpha-synuclein reveals fibril polymorphs with a common structural kernel, Nat. Commun 9 (2018) 3609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Guerrero-Ferreira R, Taylor NM, Mona D, Ringler P, Lauer ME, Riek R, Britschgi M, Stahlberg H, Cryo-EM structure of alpha-synuclein fibrils, elife 7 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tycko R, Solid-state NMR studies of amyloid fibril structure, Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 62 (2011) 279–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gremer L, Scholzel D, Schenk C, Reinartz E, Labahn J, Ravelli RBG, Tusche M, Lopez-Iglesias C, Hoyer W, Heise H, Willbold D, Schroder GF, Fibril structure of amyloid-beta(1–42) by cryo-electron microscopy, Science 358 (2017) 116–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kollmer M, Close W, Funk L, Rasmussen J, Bsoul A, Schierhorn A, Schmidt M, Sigurdson CJ, Jucker M, Fandrich M, Cryo-EM structure and polymorphism of abeta amyloid fibrils purified from Alzheimer’s brain tissue, Nat. Commun 10 (2019) 4760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhang XM, Patel AB, de Graaf RA, Behar KL, Determination of liposomal encapsulation efficiency using proton NMR spectroscopy, Chem. Phys. Lipids 127 (2004) 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Paravastu AK, Qahwash I, Leapman RD, Meredith SC, Tycko R, Seeded growth of beta-amyloid fibrils from Alzheimer’s brain-derived fibrils produces a distinct fibril structure, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106 (2009) 7443–7448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kurouski D, Van Duyne RP, Lednev IK, Exploring the structure and formation mechanism of amyloid fibrils by Raman spectroscopy: a review, Analyst 140 (2015) 4967–4980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhaliazka K, Kurouski D, Nanoscale characterization of parallel and antiparallel beta-sheet amyloid Beta 1–42 aggregates, ACS Chem. Neurosci 13 (2022) 2813–2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhou L, Kurouski D, Structural characterization of individual alpha-synuclein oligomers formed at different stages of protein aggregation by atomic force microscopy-infrared spectroscopy, Anal. Chem 92 (2020) 6806–6810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ruggeri FS, Benedetti F, Knowles TPJ, Lashuel HA, Sekatskii S, Dietler G, Identification and nanomechanical characterization of the fundamental single-strand protofilaments of amyloid alpha-synuclein fibrils, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 115 (2018) 7230–7235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ruggeri FS, Longo G, Faggiano S, Lipiec E, Pastore A, Dietler G, Infrared nanospectroscopy characterization of oligomeric and fibrillar aggregates during amyloid formation, Nat. Commun 6 (2015) 7831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ruggeri FS, Vieweg S, Cendrowska U, Longo G, Chiki A, Lashuel HA, Dietler G, Nanoscale studies link amyloid maturity with polyglutamine diseases onset, Sci. Rep 6 (2016) 31155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ramer G, Ruggeri FS, Levin A, Knowles TPJ, Centrone A, Determination of polypeptide conformation with nanoscale resolution in water, ACS Nano 12 (2018) 6612–6619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rizevsky S, Matveyenka M, Kurouski D, Nanoscale structural analysis of a lipid-driven aggregation of insulin, J. Phys. Chem. Lett 13 (2022) 2467–2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Matveyenka M, Rizevsky S, Kurouski D, Unsaturation in the fatty acids of phospholipids drastically alters the structure and toxicity of insulin aggregates grown in their presence, J. Phys. Chem. Lett 4563–4569 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Matveyenka M, Rizevsky S, Kurouski D, Length and unsaturation of fatty acids of phosphatidic acid determines the aggregation rate of insulin and modifies the structure and toxicity of insulin aggregates, ACS Chem. Neurosci 13 (2022) 2483–2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Matveyenka M, Rizevsky S, Kurouski D, Amyloid aggregates exert cell toxicity causing irreversible damages in the endoplasmic reticulum, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. basis Dis 1868 (2022), 166485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Matveyenka M, Rizevsky S, Pellois JP, Kurouski D, Lipids uniquely alter rates of insulin aggregation and lower toxicity of amyloid aggregates, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1868 (2023), 159247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Alza NP, Iglesias Gonzalez PA, Conde MA, Uranga RM, Salvador GA, Lipids at the crossroad of alpha-synuclein function and dysfunction: biological and pathological implications, Front. Cell. Neurosci 13 (2019) 175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Galvagnion C, The role of lipids interacting with -synuclein in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease, J. Parkins. Dis 7 (2017) 433–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Galvagnion C, Brown JW, Ouberai MM, Flagmeier P, Vendruscolo M, Buell AK, Sparr E, Dobson CM, Chemical properties of lipids strongly affect the kinetics of the membrane-induced aggregation of alpha-synuclein, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113 (2016) 7065–7070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhaliazka K, Rizevsky S, Matveyenka M, Serada V, Kurouski D, Charge of phospholipids determines the rate of lysozyme aggregation but not the structure and toxicity of amyloid aggregates, J. Phys. Chem. Lett 13 (2022) 8833–8839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Popova LA, Kodali R, Wetzel R, Lednev IK, Structural variations in the cross-beta core of amyloid beta fibrils revealed by deep UV resonance raman spectroscopy, J. Am. Chem. Soc 132 (2010) 6324–6328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Srinivasan S, Patke S, Wang Y, Ye Z, Litt J, Srivastava SK, Lopez MM, Kurouski D, Lednev IK, Kane RS, Colon W, Pathogenic serum amyloid a 1.1 shows a long oligomer-rich fibrillation lag phase contrary to the highly amyloidogenic non-pathogenic SAA2.2, J. Biol. Chem 288 (2013) 2744–2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Shashilov V, Xu M, Ermolenkov VV, Fredriksen L, Lednev IK, Probing a fibrillation nucleus directly by deep ultraviolet raman spectroscopy, J. Am. Chem. Soc 129 (2007) 6972–6973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Xu M, Shashilov V, Lednev IK, Probing the cross-beta core structure of amyloid fibrils by hydrogen-deuterium exchange deep ultraviolet resonance Raman spectroscopy, J. Am. Chem. Soc 129 (2007) 11002–11003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Xu M, Shashilov VA, Ermolenkov VV, Fredriksen L, Zagorevski D, Lednev IK, The first step of hen egg white lysozyme fibrillation, irreversible partial unfolding, is a two-state transition, Protein Sci 16 (2007) 815–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kurouski D, Lu X, Popova L, Wan W, Shanmugasundaram M, Stubbs G, Dukor RK, Lednev IK, Nafie LA, Is supramolecular filament chirality the underlying cause of major morphology differences in amyloid fibrils? J. Am. Chem. Soc 136 (2014) 2302–2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Levental I, Levental KR, Heberle FA, Lipid rafts: controversies resolved, mysteries remain, Trends Cell Biol 30 (2020) 341–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Michaelson DM, Barkai G, Barenholz Y, Asymmetry of lipid organization in cholinergic synaptic vesicle membranes, Biochem. J 211 (1983) 155–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].van Meer G, Voelker DR, Feigenson GW, Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 9 (2008) 112–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Pope S, Land JM, Heales SJ, Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegeneration; cardiolipin a critical target? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777 (2008) 794–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Alecu I, Bennett SAL, Dysregulated lipid metabolism and its role in alpha-synucleinopathy in Parkinson’s disease, Front. Neurosci 13 (2019) 328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].La Rosa C, Scalisi S, Lolicato F, Pannuzzo M, Raudino A, Lipid-assisted protein transport: a diffusion-reaction model supported by kinetic experiments and molecular dynamics simulations, J. Chem. Phys 144 (2016), 184901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Scollo F, Tempra C, Lolicato F, Sciacca MFM, Raudino A, Milardi D, La Rosa C, Phospholipids critical micellar concentrations trigger different mechanisms of intrinsically disordered proteins interaction with model membranes, J. Phys. Chem. Lett 9 (2018) 5125–5129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Rizevsky S, Zhaliazka M, Dou T, Matveyenka M, Characterization of substrates and surface-enhancement in atomic force microscopy infrared (AFM-IR) analysis of amyloid aggregates, J. Phys. Chem. C 126 (2022) 4157–4162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kurouski D, Lombardi RA, Dukor RK, Lednev IK, Nafie LA, Direct observation and pH control of reversed supramolecular chirality in insulin fibrils by vibrational circular dichroism, Chem. Commun 46 (2010) 7154–7156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Sarroukh R, Goormaghtigh E, Ruysschaert JM, Raussens V, ATR-FTIR: a “rejuvenated” tool to investigate amyloid proteins, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013 (1828) 2328–2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Cataldi R, Chia S, Pisani K, Ruggeri FS, Xu CK, Sneideris T, Perni M, Sarwat S, Joshi P, Kumita JR, Linse S, Habchi J, Knowles TPJ, Mannini B, Dobson CM, Vendruscolo M, A dopamine metabolite stabilizes neurotoxic amyloid-beta oligomers, Commun. Biol 4 (2021) 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Shahmoradian SH, Lewis AJ, Genoud C, Hench J, Moors TE, Navarro PP, Castano-Diez D, Schweighauser G, Graff-Meyer A, Goldie KN, Sutterlin R, Huisman E, Ingrassia A, Gier Y, Rozemuller AJM, Wang J, Paepe A, Erny J, Staempfli A, Hoernschemeyer J, Grosseruschkamp F, Niedieker D, El-Mashtoly SF, Quadri M, Van IWFJ, Bonifati V, Gerwert K, Bohrmann B, Frank S, Britschgi M, Stahlberg H, Van de Berg WDJ, Lauer ME, Lewy pathology in Parkinson’s disease consists of crowded organelles and lipid membranes, Nat. Neurosci 22 (2019) 1099–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Killinger BA, Melki R, Brundin P, Kordower JH, Endogenous alpha-synuclein monomers, oligomers and resulting pathology: let’s talk about the lipids in the room, NPJ Parkinsons. Dis 5 (2019) 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Zhaliazka K, Mateyenka M, Kurouski D, Lipids uniquely alter the secondary structure and toxicity of amyloid beta 1–42 aggregates, FEBS J (2023), 10.1111/febs.16738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Galvagnion C, Buell AK, Meisl G, Michaels TC, Vendruscolo M, Knowles TP, Dobson CM, Lipid vesicles trigger alpha-synuclein aggregation by stimulating primary nucleation, Nat. Chem. Biol 11 (2015) 229–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Zhu M, Fink AL, Lipid binding inhibits alpha-synuclein fibril formation, J. Biol. Chem 278 (2003) 16873–16877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.