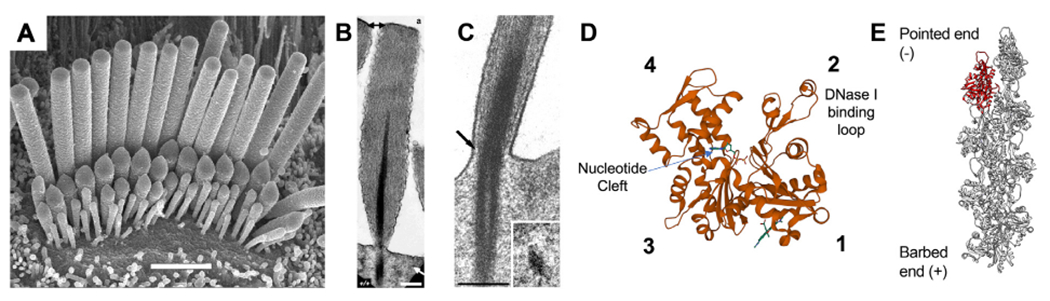

Fig. 1.

The actin cytoskeleton in hair cell stereocilia. (A) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of a cochlear hair cell, demonstrating the graded stereocilia sizes that contribute to the hair bundle architecture. Row 1 stereocilia are the tallest, with the shorter rows 2 + 3 having active MET channels gated by bundle deflection. Scale bar is 2 μm. (B) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of a sectioned stereocilia revealing its highly ordered core of actin filaments. The rootlet structure is darkly stained and penetrates into the stereocilia and cuticular plate. Scale bar is 250 nm. (C) TEM image of the stereocilia taper region demonstrating how the rootlet deforms during stereocilia deflection. (D) Structural model of an actin monomer (PDB: 1J6Z) with subdomains 1–4 and the nucleotide binding cleft labeled. The DNase I binding loop (D-loop) forms part of the interface between adjacent protomers in a filament. (E) Structural model of an actin filament (PDB: 6BNO) with an individual monomer highlighted in red. Actin filaments have structural polarity with a fast-growing barbed end and a pointed end where depolymerization occurs. Images reproduced with permission from: (A) Beurg M, et al. (2006) Journal of Neuroscience 26 (43) 10,992–11,000, DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2188-06.2006, Copyright © 2006, Society for Neuroscience. (B) Mogensen et al. (2007) Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 64 (7): 496–508, DOI: 10.1002/cm.20199. Copyright © 2007, Wiley-Liss, Inc. (C) Furness et al. (2008) Journal of Neuroscience 28 (25): 6342–53, DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1154-08.2008, Copyright © 2008, Society for Neuroscience. Molecular structures were rendered in VMD and Chimera.