Abstract

Vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) is one of the primary factors promoting angiogenesis in endothelial cells. Although defects in VEGF-A signaling are linked to diverse pathophysiological conditions, the early phosphorylation-dependent signaling events pertinent to VEGF-A signaling remain poorly defined. Hence, a temporal quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis was performed in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) treated with VEGF-A-165 for 1, 5 and 10 min. This led to the identification and quantification of 1971 unique phosphopeptides corresponding to 961 phosphoproteins and 2771 phosphorylation sites in total. Specifically, 69, 153, and 133 phosphopeptides corresponding to 62, 125, and 110 phosphoproteins respectively, were temporally phosphorylated at 1, 5, and 10 min upon addition of VEGF-A. These phosphopeptides included 14 kinases, among others. This study also captured the phosphosignaling events directed through RAC, FAK, PI3K-AKT-MTOR, ERK, and P38 MAPK modules with reference to our previously assembled VEGF-A/VEGFR2 signaling pathway map in HUVECs. Apart from a significant enrichment of biological processes such as cytoskeleton organization and actin filament binding, our results also suggest a role of AAK1-AP2M1 in the regulation of VEGFR endocytosis. Taken together, the temporal quantitative phosphoproteomics analysis of VEGF signaling in HUVECs revealed early signaling events and we believe that this analysis will serve as a starting point for the analysis of differential signaling across VEGF members toward the full elucidation of their role in the angiogenesis processes.

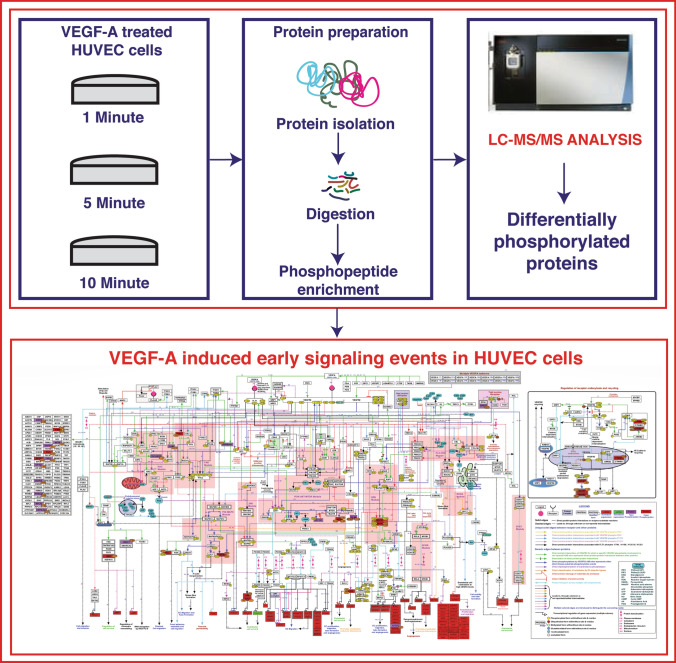

Graphical abstract

Workflow for the identification of early phosphorylation events induced by VEGF-A-165 in HUVEC cells

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12079-023-00736-z.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, VEGF-A, HUVEC, Phosphoproteomics, Cytoskeleton organization

Introduction

Angiogenesis, the sprouting of capillaries from preexisting vasculature, is central to diverse physiological processes from embryogenesis to wound healing, and in pathological processes from inflammatory diseases to cancer (Folkman 1971; Tonnesen et al. 2000; Carmeliet and Jain 2000; Nishida et al. 2006; Chatterjee et al. 2013). Endothelial cells contribute distinct mechanical and biological functions that involve cell proliferation, migration and tube formation attributed to angiogenesis (Bouïs et al. 2006; Carmeliet and Jain 2011). This dynamic process is fine-tuned through an intricate signaling network by the pro- and anti-angiogenic factors. Alteration in the balance between these growth factors expedite pathological angiogenesis, as is manifested in diabetic retinopathy, age related macular degeneration, rheumatoid arthritis, tumor growth, and metastasis (Folkman and Klagsbrun 1987; Folkman and Shing 1992; Ng and Adamis 2005; Oklu et al. 2010; Aguilar-Cazares et al. 2019).

Angiogenesis is governed by an array of factors, principally vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and angiopoietins (Davis et al. 1996; Petrova et al. 1999; Nugent and Iozzo 2000). Among them, VEGF-A signaling through VEGF receptor tyrosine kinases (VEGFRs) contributes to angiogenesis. The VEGF-A family comprises six members: VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, and VEGF-E and placental growth factor (PlGF); their biological effects are mediated via three cell surface receptors, namely, VEGFR1 (Flt-1), VEGFR2 (KDR/Flk-1) and VEGFR3 (Flt-4) (Ferrara et al. 1992; Ferrara 1999; Ortega et al. 1999). In endothelial cells (EC), signaling mediated by the VEGF-A-165/VEGFR2 interaction imparts significant cellular responses, including mitogenic and survival signals. The complete model pathway map of known events involved in the VEGF-A signaling in endothelial cells was previously assembled by our team (Abhinand et al. 2016; Sunitha et al. 2019). Briefly, binding of VEGFA-165 to VEGFR2 results in the autophosphorylation and subsequent activation of RAS-MAPK, PI3K-AKT-mTOR, PLC-PKC, JAK-STAT, NF-κB, p38MAPK-FAK, and Wnt signaling pathways (Holmes et al. 2007; Dejana 2010; Koch et al. 2011; Soumya et al. 2016). The interplay between these pathways contributes to endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and survival, as well as tube formation involved in the angiogenic process (Lohela et al. 2009).

Among the diverse post-translational modifications (PTMs), phosphorylation is one of the most studied PTMs and is established as a significant player in the regulation of protein function (Mann and Jensen 2003; Rahimi and Costello 2015). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) are commonly used models to study angiogenesis in vitro. VEGF-A mediated alteration in protein expression in HUVECs was reported at the 4 and 24-h time scale (Pawlowska et al. 2005), and phosphorylation events were previously captured at various time points from 10 to 60 min (Zhuang et al. 2013). However, an analysis of the dynamic phosphorylation events at very early time points (1–10 min) remains to be investigated. In this study, we employed a non-targeted quantitative phosphoproteomic approach to explore the phosphosite-dependent signaling events regulated by VEGF-A at early time scales (1, 5 and 10 min) in HUVECs. We detected a total of 1971 phosphopeptides belonging to 961 phosphoproteins at all time points. Among these, 251 phosphopeptides belonging to 195 phosphoproteins were found to be significantly differentially phosphorylated within the first 10 min of VEGF-A treatment. These findings shed light on the earliest VEGF-A mediated signaling processes. The same method may be used to evaluate the efficacy and mode of action of anti-angiogenic compounds to treat pathological angiogenesis.

Materials and methods

Cell Culture and protein extraction

Three separate tubes of a HUVEC single donor cell line were obtained from PromoCell (Cat. No.: C-12200; Lot number: 425Z002) and maintained in MCDB 131 media supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 2 mM L-alanyl-L-glutamine dipeptide (Gibco™ GlutaMAX™), and 100 U/mL penicillin–streptomycin in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. At passage 5, 4.5 × 105 cells were plated per 100 mm dish and allowed to settle. After starving the cells overnight in FBS-free medium (same composition as above, but omitting FBS), the medium was replaced with FBS-free medium supplemented with 50 ng/mL human recombinant VEGF-A-165, produced in Escherichia coli (PeproTech, Inc.) (Yu et al. 2017) for three different intervals (1, 5, and 10 min). Untreated HUVEC cells were used as control. All conditions were performed in triplicates. The cells were washed once in 1X PBS, and scraped using 1 mL of lysis buffer A [6 M guanidinium chloride, 10 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine, 40 mM 2-chloroacetamide, 100 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane-hydrochloric acid (pH 8.5)] and stored at -80°C until use. The extracted protein was then diluted in lysis buffer B [12 mM sodium deoxycholate, 12 mM sodium N-dodecanoylsarcosinate, 100 mM tetraethylammonium bromide (TEAB) (pH 8.5), 1% protease inhibitor cocktail and phosphatase inhibitor 2/3 cocktails (P2714, P5726 and P0044, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)], and heated at 95°C for 5 min, cooled on ice for 15 min, sonicated (Branson probe sonifier output 3–4, 50% duty cycle, 3 times 30 s), and heated again (95°C for 5 min). The protein concentration of each sample was quantified using a Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific).

Sample preparation for phosphopeptide enrichment

HUVEC cell lysate (50 µg total protein in 250 µL of lysis buffer B) was reacted in 9.9 mM dithiothreitol for 30 min at 37°C, followed by 47.2 mM iodoacetamide for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. After fivefold dilution with 100 mM TEAB buffer (pH 8.5), proteins were digested with 2.8 µg of Lys-C (Wako, Osaka, Japan) for 3 h at 37°C followed by 2.5 µg of trypsin (Promega, Medison, WI, USA) for 16 h at 37°C. The reaction was quenched by acidification with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), and the protein digests were subjected to clean-up using C18 stage tips (Rappsilber et al. 2003). Phosphopeptides in the elution were enriched using TiO2-based hydroxy acid-modified metal oxide chromatography (HAMMOC) (Sugiyama et al. 2007). The samples were concentrated using C18 stage tips, dried, and stored at -80℃ until analysis.

LC–MS/MS analysis

Each protein digest was dissolved with 12 µL of 0.1% TFA 5% acetonitrile (ACN), and 5 µL of the sample was loaded on a self-packed capillary column (Reprosil-Pur C18 materials, Dr. Maisch GmbH, Germany, 100 µm × 130 mm. 5 µm tip i.d.) using an HTC-PAL autosampler (CTC Analytics, Zwingen, Switzerland). The peptides in the samples were separated using an UltiMate 3000 nanoLC Pump (Dionex Co., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). As a mobile phase, a mixture of (A) acetic acid/water (0.5:100, v/v), (B) acetic acid/acetonitrile (0.5:100, v/v) and (C) acetic acid/dimethyl sulfoxide (0.5:100, v/v) were used at the flow rate of 500 nL/min [(A) + (B) = 96%, (C) = 4%, (B) 0–4% (0–5 min), 4–24% (5–65 min), 24–76% (65–70 min), 76% (70–80 min), and 0% (80.1–120 min)]. The separated peptides were ionized at 2400 V, injected into LTQ orbitrap XL ETD (Thermo Electron, San Jose, CA, USA) and detected as peptide ions (mass scan range: m/z 400–1500, mass resolution: 60,000 at m/z 400). Top 10 peaks of multiple charged peptide ions were subjected to collision-induced dissociation (isolation width: 2 Th, normalized collision energy: 35 V, activation Q: 0.25, activation time: 30 ms). All samples were analyzed in duplicate. The raw data and the related files were deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository with the data set identifier (PXD038133).

Identification and quantitative analysis of phosphoproteins

The LC–MS/MS raw data were searched against the human RefSeq database (release 109) appended with frequently observed contaminants (116 entries) from The Global Proteome Machine (GPM) common Repository of Adventitious Proteins (cRAP) (released on 01.01.2012) using Mascot (Koenig et al. 2008) and SEQUEST HT (Eng et al. 1994) search algorithms through the Proteome Discoverer platform (version 2.2, Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany). Carbamidomethylation of cysteine was analyzed as static modification, while, oxidation of methionine, N-terminal acetylation, phosphorylation at serine (S), threonine (T), and tyrosine (Y) were set as variable modifications by considering a maximum missed cleavage of two. The precursor mass error tolerance and fragment mass error tolerance were set to 10 ppm and 0.05 Da, respectively. The data were also searched against a decoy database and 1% false discovery rate was considered at peptide spectrum match, peptides and protein levels for sequence identification. The localization probability of phosphorylated site was calculated using the PTM-RS node (Version 3.0) (Taus et al. 2011; Ramsbottom et al. 2022) in the Proteome Discoverer, and the identified phosphopeptides with more than 75% probability (with accurate false localization rate calculations) were used for bioinformatics analysis. The raw abundance values of phosphopeptides were normalized using a smooth quantile normalization method implemented in R (version 3.6.1) using the “qsmooth” function. Phosphopeptides with a ± 1.3-fold-change of the normalized value compared to the control (Student’s t-test p-value ≤ 0.05) were considered as up- or down-regulated phosphorylation at different time points.

Bioinformatics analysis

The PTM-pro online tool (http://ptm-pro.inhouseprotocols.com/) (Patil et al. 2018) was used to profile high confidence (best site probability score > 75%) S/T/Y phosphorylation sites on the peptides. These phosphosites were subjected to motif analysis using the motif-x algorithm (Chou and Schwartz 2011) from the MOMO suite (Cheng et al. 2019) provided in the PTM-pro tool. The differentially phosphorylated proteins were classified and categorized based on Gene Ontology analysis using the g:Profiler functional annotation tool (https://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/gost) (Raudvere et al. 2019). Protein–protein interaction analysis was performed using STRING, a functional protein association networks database (Szklarczyk et al. 2021). The hub proteins were captured using the CytoHubba plugin in Cytoscape 3.7.1 (Chin et al. 2014). For statistical comparison, Student’s t-test was implemented using R (version 3.6.1), and p-value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Kinase enrichment analysis was performed using the online tool eXpression2Kinases (X2K; http://amp.pharm.mssm.edu/X2K/) (Clarke et al. 2018) for phosphoproteins enriched with genes known to interact with kinases. The kinome map was built using the KinMap tool (http://www.kinhub.org/kinmap/index.html) (Eid et al. 2017). The list of identified kinases was searched and relevant kinases were highlighted on the kinome map. The phosphosites that were previously reported to be associated with VEGF-A signaling in HUVECs were represented using the PathVisio tool. The phosphoprotein sites were distinguished in brown on the map.

Results

Quantitative phosphoproteomics of VEGF-A signaling in HUVEC cells

To explore the dynamic phosphosites and signaling responses mediated by VEGF-A in HUVEC cells, we analyzed the temporal phosphoproteomic changes through a label-free quantitative phosphoproteomics approach. To achieve this, the cells were treated with VEGF-A at time intervals of 1, 5 and 10 min. The mass spectrometry experiments were carried out in duplicates and quantile-normalized before further analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). We identified 1996 phosphopeptides corresponding to 964 phosphoproteins at a false discovery rate of 1% (Supplementary Table 1). The extraction of high-confidence phosphorylation sites (> 75% PTM site probability score) using the PTM-pro tool resulted in the identification of 2771 PTM sites localized on 1971 phosphopeptides that corresponded to 961 phosphoproteins. Among them, 1605 were found to be phosphorylated at a single site and 366 peptides at more than one site. Altogether, we observed a higher occurrence of phosphorylation on serine (2235) followed by threonine (468) and tyrosine (68) (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Phosphoproteome profile of VEGF-A-treated HUVEC cells. a Phosphorylation site profile of the total phosphoproteins identified. b, c, and d Volcano plots depicting the differentially phosphorylated peptides at 1 min, 5 min and 10 min, respectively, relative to untreated control. Blue dots depict hyper-phosphorylation, while green dots depict hypo-phosphorylation

Gene Ontology (GO) based analysis of global phosphoproteome revealed significant enrichment of biological processes, including organelle organization, cytoskeleton organization, actin filament-based processes, regulation of cellular component organization, regulation of mRNA metabolic process, macromolecule localization, and intracellular signal transduction. Notably, 208 phosphoproteins found to be phosphorylated in our study were known to be involved in cytoskeleton organization, 122 in cell adhesion, 132 in cell migration, and 152 in apoptosis, all of which are processes that are important in angiogenesis (Lohela et al. 2009). In addition, biological pathways/processes such as VEGF-A signaling, focal adhesion, MAPK signaling, endocytosis, proteoglycans in cancer, regulation of actin cytoskeleton, ErbB signaling, HIF-1 signaling, AMPK signaling, mTOR signaling, AGE-RAGE signaling, PI3K-Akt signaling, and IL-17 signaling pathways were enriched for these phosphoproteins.

Characterization of VEGF-A-regulated temporal phosphoproteome in HUVEC cells

To characterize the differentially phosphorylated phosphoproteins upon VEGF-A stimulation, at different time points, both the qualitative and quantitative features of these phosphoproteins were considered. Across the samples in three different time points, we identified 69, 153, and 133 differentially phosphorylated peptides corresponding to 62, 125, and 110 phosphoproteins at 1 min, 5 min, and 10 min, respectively (Supplementary table 2). Among the 69 differentially phosphorylated peptides corresponding to 62 phosphoproteins in 1 min, 38 were hyper-phosphorylated and 31 were hypo-phosphorylated (Fig. 1b). At 5 min, 75 peptides were hyper-phosphorylated and 78 were hypo-phosphorylated (Fig. 1c). At 10 min, 68 were hyper-phosphorylated and 65 were hypo-phosphorylated (Fig. 1d). There were 20 phosphoproteins differentially phosphorylated at all time points (Fig. 2a). This included the consistent hyper-phosphorylation of SLK [S340; S779], hypo-phosphorylation of AP2M1 [T156], and dynamic regulation of different phosphorylation sites on 18 proteins (AHNAK, AKAP12, ARHGAP29, ATF2, EIF4B, EML3, FNBP1, HDGFL2, HSPB1, ITPRID2, MAP1B, MAST4, MYL12A, PHLDB1, RALY, TP53I11, MAP4, and TPR).

Fig. 2.

Dynamic PPI network of differentially phosphorylated proteins. a The heat map depicts the variation in the abundance of phosphopeptides corresponding to 20 differentially phosphorylated phosphoproteins. b Protein–protein interaction network of all proteins corresponding to differentially phosphorylated peptides across all time-points along with their interactors forming a highly interactive network. The top 10 major interactors are highlighted in red

Among the 84 phosphorylation sites that corresponded to 69 differentially phosphorylated peptides at 1 min, 73 were Serine phosphorylated, 9 were Threonine phosphorylated, and 1 was Tyrosine phosphorylated. Out of the 179 phosphorylation sites that corresponded to 153 differentially phosphorylated peptides identified in 5 min, most of them were phosphorylated on serine (158), followed by threonine (19) and tyrosine (2) sites. At 10 min, 140 serine, 26 threonine and 4 tyrosine phosphosites were captured for 170 phosphorylation sites, corresponding to 133 differentially phosphorylated peptides.

The Gene Ontology (GO)-based biological processes enrichment analysis was performed on the differentially phosphorylated proteins in each time point. GO enrichment analysis of the hyper- and hypo-phosphorylated proteins at 1 min revealed significant enrichment of biological processes including cytoskeleton organization, cellular component organization, mitotic cell cycle process, and signaling by Rho GTPases. The cytoskeleton organization, apoptotic process, cell adhesion molecule binding, MTOR signaling and VEGFA-VEGFR2 signaling pathway were also observed related to the differentially phosphorylated proteins at 5 min. The hyper- and hypo-phosphoproteins at 10 min were mainly involved in biological processes including cytoskeletal protein binding, cell adhesion molecule binding, structural constituent of the cytoskeleton, MAPK signaling pathway, mTOR signaling pathway, VEGF-A signaling pathway, and HIF-1 signaling pathway. Together, GO analysis of the multi-time point differential phosphoproteins shows that VEGF-A-induced signaling primarily targets cytoskeleton organization at early time points (Supplementary Table 3).

Integrated protein–protein interaction network analysis of phosphoproteins regulated by VEGF-A in HUVEC cells

The protein–protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed based on the information retrieved from the STRING database. The interaction network of differentially phosphorylated proteins corresponding to specific time points and their interactors were visualized in STRING and were integrated using Cytoscape (Fig. 2b). The data used here is restricted to experimental datasets, literature mining and databases and excludes co-expression, neighborhood, gene fusion and co-occurrence-based entries. The hub proteins in the PPI network were further identified using the CytoHubba plugin in Cytoscape (Chin et al. 2014). Based on the node degree, the top ten proteins were ranked and selected as hub proteins. This included GAPDH, JUN, TP53, CDH1, HSP90AA1, FN1, RPS6, EP300, HNRNPC and SNRPD3 proteins. Further, we analyzed the abundance of phosphopeptides across the time points and confirmed that the top two hub proteins, GAPDH and JUN, were significantly hyper-phosphorylated at 5 and 10 min.

Phosphorylation alteration in protein kinases by VEGF-A signaling

The role of protein kinases in signaling events is indisputable. Therefore, we sought to identify kinases that might be involved in angiogenesis upon VEGF-A stimulation. Among the 961 phosphoproteins described above, 55 were identified as kinases based on kinase enrichment analysis. These kinases were then mapped in a kinome tree using the KinMap tool (Fig. 3a). The kinome tree classified the kinases into eight typical groups. The classification into kinase families for the 55 kinases containing phosphopeptides is found in Table 1. Among these, 14 were differentially phosphorylated in VEGF-A-treated HUVEC cells, among which six (MAP2K2, MAPK1, MAPK3, PAK2, SLK, TRIM28) were hyper-phosphorylated and another eight (AAK1, CDC42BPB, CDK16, MAST4, STK17A, STK39, PRPF4B, TNIK) were hypo-phosphorylated within 10 min of VEGF-A treatment in HUVEC cells (Table 1, italic and bold, respectively). Further, we sought to analyze the phosphosites that regulate the kinase activity of these 14 kinases. We identified the Y204 site in MAPK3, Y187 site in MAPK1 and S473 site in TRIM28 kinases to be induced at 10 min, and the S141 site in PAK2 was induced at both 1 min and 5 min. Through its T394 phosphosite, MAP2K2 was also enzymatically activated at 10 min. Apart from that, sites involved in other enzyme activities (T169 in PAK2 kinase) were also detected at 1 min and 5 min.

Fig. 3.

Kinase enrichment and transcriptome integration of differentially phosphorylated proteins. a The kinome map depicting the identified kinases as dots. b Circose plot depicting the integration of differentially phosphorylated proteins with a previously published differentially regulated transcriptome (Sunitha P et al. 2019). The outer lane shows the chromosome boundaries, middle lane corresponds to differentially regulated transcripts, and the inner lane corresponds to proteins with differentially phosphorylated peptides. The genes highlighted in red, blue and green corresponded to synchronization of phosphoproteome and transcriptome data at early, mid and late timeframes considered in the transcriptome analysis

Table 1.

Phosphorylated and differentially phosphorylated kinases and their classification

| Kinase group | Phosphorylated Kinases |

|---|---|

| ACG | CDC42BPB, GRK5, MAST4, PDPK1, PKN1, PKN2, PRKCA |

| CAMK | CASK, CAMK2D, MARK2, MARK3, PRKD2, RPS6KA4, STK17A, TRIO |

| CMGC | CDK2, CDK7, CDK16, CDK17, DYRK1A, GSK3A, GSK3B, MAPK1, MAPK3, PEAK1, PRPF4B, SRPK1 |

| CK1 | CSNK1G3 |

| STE | MAP2K2, MAP3K15, MAP4K3, MAP4K4, MAP4K5, MINK1, OXSR1, PAK2, PAK4, SLK, STK10, STK39, TAOK1, TNIK |

| TK | LCK, LYN |

| TLK | KSR1, MAP3K11 |

| Analytical protein kinases | BRD3, BRD4, TRIM28 |

| Others | AAK1, NEK1, NRBP1, WNK1 |

Kinases that were phosphorylated in this study are listed by kinase group; among these, significantly hyper-phosphorylated and hypo-phosphorylated kinases appear in bold and italic, respectively.

Differentially phosphorylated proteins at various time points were analyzed to capture the downstream signaling pathways by kinase enrichment analysis using eXpression2Kinases online tool. The analysis revealed the enrichment of MAPK1, MAPK3, MAPK8, MAPK14, CDK1, CDK2, CDK4, ERK1, ERK2, JUK1, JUK2, AKT1, GSK3B, CK2ALPHA, HIPK2, DNAPK, ABL1, MAP2K1 and CDC2 as downstream kinases of the differentially phosphorylated kinases identified. Furthermore, we confirmed that VEGF-A-mediated signaling in HUVEC cells is mediated through the activation of highly connected kinases including CDKs, ERKs and AKT1.

Comparative analysis of core transcriptome and phosphoproteome induced by VEGF-A in HUVECs

The temporal gene expression profiles induced by VEGF-A in HUVECs previously assembled by our team were used for integrative analysis with the current phosphoproteomics data. Sunitha et al. (2019) had identified 2552 mRNAs that were differentially regulated by VEGF-A in HUVECs and among them, 494 mRNAs were reported to be regulated in the earlier time frames of the dataset (0 min–1 h, according to the data categorization adopted by Sunitha et al. 2019). Integration with the VEGF-A-induced phosphoproteome data described here showed/confirmed the presence of the phosphoproteins HMGN1, C17orf75, RABL6, IGFBP3 and HNRNPU in both datasets. In addition, we identified 17 genes captured in intermediate (1–6 h) time points (AKAP12, ARFGEF2, CRIP2, DBN1, EPB41L3, FIP1L1, HNRNPA1, IGF2R, IGFBP3, MYH9, NES, NUCKS1, PRKAB2, TNS3, TSC2, VEPH1, and ZC3HAV1) and 7 genes in the later (6–24 h) time points (AAK1, CTNND1, DSP, EIF4G1, EXOSC9, JUP, and MRE11). Among these genes, TSC2 and EIF4G1 were involved in the mTOR signaling pathway, MRE11, TSC2 and IGFBP3 in cellular senescence, and JUP and EPB41L3 were a part of cytoskeletal protein-membrane anchor activity (Fig. 3b).

Analysis of conserved motifs of phosphosites regulated by VEGF

Motif analysis was performed through the ‘motif-x’ algorithm to identify the conserved motifs of the phosphorylation sites identified to be regulated by VEGF-A. Our study revealed 20 conserved motifs around serine phosphorylation and three around threonine phosphorylation in the early phase of VEGF-A-induced phosphorylation. Among the 23 motifs, ten were proline-directed S/T phosphorylation motifs (Supplementary Fig. 2). These motifs are reported to be central to multiple signaling pathways that regulate cell proliferation, orchestrated mainly by extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) (Torres 2003; Wu et al. 2010). Another critical motif RxxS/T which is a binding site for protein kinase A (PKA) was also identified in our dataset (6 motifs around serine phosphorylation), suggesting the activation of several downstream metabolic processes (Grønborg et al. 2002; Bruce et al. 2002; O'Flaherty et al. 2004; Sparks et al. 2011). Additionally, motifs containing acidic amino acids (aspartic acid and glutamic acid) that are consensus binding sites for serine/threonine kinases were also found to be highly enriched (5 motifs around serine phosphorylation) (Seldin and Leder 1994).

Representation of early phosphorylation events in the integrated VEGF-A Signaling network map in HUVECs

We compared phosphoproteomic data generated from the present study with an extensively curated VEGF-A/VEGFR2 signaling pathway map published previously by our group (Abhinand et al. 2016; Sunitha et al. 2019). In comparison, our current study reported 20 phosphoproteins in common with previous studies and a number of phosphosites in 33 phosphoproteins that were not reported or assembled in the earlier update of the pathway (Sunitha et al. 2019). Interestingly, among the additional phosphoproteins identified, 12 are known to interact with BCAR1, a docking protein involved in actin cytoskeletal dynamics, cell motility and angiogenesis. We also observed an overlap in some of the crucial signaling modules including the RAC, FAK, PI3K-AKT-MTOR, ERK, and P38 MAPK modules, tight junction distribution, and receptor endocytosis (Fig. 4). We further examined the association of each differentially phosphorylated proteins obtained in the current study with these signaling modules. The RAC module consisted of FLNB and CDC42BPB. The FAK signaling module consisted of NCK1. RPS6 and AKT1S1 in the PI3K-AKT-MTOR module. The P38 MAPK pathway included HSPB1, and the ERK signaling pathway included MAPK1 and MAPK3. In addition, EPS15 was included in tight junction distribution and MAPK1, MAPK2, MAPK3, CTNND1, and CTNNA1 in receptor endocytosis.

Fig. 4.

Representation of the protein phosphosites that overlapped with prior studies on VEGF-A signaling. VEGF-A induced protein phosphorylation in HUVECs were extracted and incorporated in our previous model (Abhinand et al. 2016). The differentially phosphorylated proteins are highlighted, (violet (hypo-phosphorylation) and dark red (hyper-phosphorylation)) with their phosphorylation site information using the Pathvisio tool

Discussion

Angiogenesis is a complex process that involves extensive interplay between endothelial cells, extracellular matrix, basement membrane, and various angiogenic factors. The endothelial cells are quiescent in normal physiological conditions and they control diverse biological and mechanical functions of blood vessels. Upon activation by hypoxia and/or altered metabolite flux, the release of proteases induces a sequence of events including degradation of the underlying basement membrane. Subsequently, the migration of endothelial cells into the interstitial space is followed by endothelial cell proliferation, cell–cell contact, and lumen formation. The generation of a new basement membrane with the recruitment of pericytes and fusion of the newly formed vessels leads to the initiation of blood flow. Finally, when sufficient neovascularization is achieved, the pro-angiogenic factors are downregulated to retain the quiescent nature of endothelial cells. Among the pro-angiogenic factors, VEGF is a well-studied growth factor which exist in diverse isoforms and VEGF-A is a pivotal modulator of endothelial cell proliferation, migration and tube formation. The tip and stalk cell are the two distinct cellular phenotypes adopted by endothelial cells during sprouting. Tip cells are directed towards avascular areas and express VEGF receptors on their filopodia to VEGF. Activation of VEGFR2 triggers multiple downstream signaling pathways relevant to angiogenesis via phosphorylation of many proteins including kinases. Recent studies have reported that targeting this signaling pathway can be an alternative strategy to combat diseases associated with aberrant angiogenesis. As the signaling mechanisms in endothelial cells drive angiogenesis, we aimed to unravel the signaling events mediated by VEGF-A in HUVECs, a widely used in vitro model, to examine the angiogenic process. The current temporal phosphoproteomics study elucidates the early signaling events mediated by VEGF-A.

Considering the importance of phosphorylation in mediating angiogenesis, the dynamics of phosphorylation of proteins in VEGF-A mediating signaling in ECs on a temporal scale are not sufficiently understood. The latest pathway map of VEGF-A/VEGFR2 signaling published from our lab included all the phosphoproteins that were identified until the year 2019. Here, we identified 56 phosphoproteins along with their phosphorylation sites within the 437 molecules already attributed to VEGF-A mediated signaling thus far. The present study overcame the scarcity of phosphorylated proteins and identified an additional 906 phosphoproteins beyond the known phosphoproteins identified through targeted low-throughput studies. Differentially phosphorylated proteins were further screened for their involvement in biological processes. This study revealed that early signaling events induced in HUVECs were mainly associated with cytoskeleton reorganization. The cytoskeleton proteins and GTPase regulators phosphorylation were also observed by Zhuang et al. (2013) in their VEGF-A induced HUVECs phosphoproteomics study. Since they had sampled the 10–60 min timeframe, our study at 1–10 min suggests that the reorganization is triggered very early on by VEGF-A. In particular, the PAK2 kinase was phosphorylated (active) at 1 min and 5 min, and MAP2K2, MAPK3, MAPK1 and TRIM28 at 10 min, all of which are known to significantly contribute to cytoskeleton reorganization. While also implicated in chromatin regulation, they are also likely to mediate several extracellular functions via RAS-RAC-PAK-MEK-ERK signaling (Santarpia et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2020). As kinases contribute to major cellular signaling events, we further performed kinome mapping and their enrichment analysis. During the early stages of VEGF-A-mediated signaling, many kinases in the STE group were differentially phosphorylated. This group of kinases is involved in cytoskeleton organization and remodeling (Zhuang et al. 2013). However, we could not identify any significantly differentially phosphorylated proteins relating to JNK, NFKB, PLC-PKC, RHOA, and STAT modules.

Although the present phosphorylation data provides detailed information on VEGF-A-induced phosphoproteome in HUVECs, due to the limitations in cell models and LC–MS/MS technology, all early signaling events may not be captured. In particular, the activation and phosphorylation of the VEGFR2 receptor itself is critical in angiogenesis, but our phosphoproteomic data did not capture VEGFR2 tyrosine phosphorylation sites in response to VEGF-A. Nevertheless, we identified VEGFR2-dependent activation of RAS-RAC-PAK-MEK-ERK signaling in HUVECs. The phosphorylation of Y951 in VEGFR2 was identified by Zhuang et al. in 2013 in their 10—60 min phosphoproteome data set, but on the other hand, they did not capture the early MAPK phosphorylation sites that we identified in our data. Also, a relatively lower number of tyrosine phosphorylation sites as compared to serine and threonine phosphorylation sites were identified at all the time points. We captured 1 peptide with phosphotyrosine modification at 1 min, 2 at 5 min and 6 at 10 min. The tyrosine phosphorylation site of AKAP12 (hypo-phosphorylated) and PGRMC2 (hyper-phosphorylated) were identified at 5 min and 10 min, respectively, showing consistency in their differential phosphorylation.

Src-FAK-Paxillin signaling is conserved in angiogenesis and controls fundamental cellular processes including focal adhesion, assembly and cell migration. Previous studies reported that Ste20-like kinase SLK is essential for focal adhesion turnover and cell migration through FAK/c-src complex signaling (Chaar et al. 2006; Wagner et al.2008). Since the activation of SLK is dependent on FAK/c-src/MAPK signaling, we followed the dynamics of SLK phosphorylation at different time points. Our phosphoproteome data revealed consistent hyper-phosphorylation of SLK at all time points compared to untreated cells. Finally, our analysis identified T156, a significant site (reported as T181 in one of the isoforms) in AP2M1, to be hypo-phosphorylated. Studies reported that this site is mainly associated with endocytosis (Conner and Schmid 2002). This suggests that the initial signaling suppresses the activation of AP2M1, thereby promoting sustenance of VEGF-A receptor on the cell surface.

Among the top ten phosphoproteins with a high degree of connectivity in the PPI network, six phosphoproteins (GAPDH, JUN, FN1, TP53, HSP90AA1, HNRNPC) were hyper-phosphorylated and one was (HSP90AA1) hypo-phosphorylated. The top 5 hub phosphoproteins (HSP90AA1, JUN, RPS6, FN1, GAPDH) were well-associated in the VEGF-A signaling map model. JUN is known to be regulated by receptor tyrosine kinase signaling pathways, forming a major signaling hub. Interestingly, we also report the evidence for the potential role of AP2-associated protein kinase 1 (AAK1) in angiogenesis. Agajanian et al. (2019) have reported that the AAK1-dependent phosphorylation of AP2M1 (T156) promotes endocytosis, and in this study’s dataset, AAK1 was hypo-phosphorylated. This may lead to the above-mentioned hypo-phosphorylation of AP2M1, which may inhibit the early endocytosis of VEGFR2 in HUVECs. We have not observed any phosphorylation sites on the membrane proteins that are currently associated with VEGF signaling including those in the VEGFRs. This demands further analysis of phosphoproteins in membrane fractions. Together, our study derived the first early phosphoproteome map of VEGF-A signaling in HUVECs and we believe that this dataset will form a reference for further analysis of multiple PTMs regulated by VEGF-A towards angiogenesis processes.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Sumiko Ohnuma for her support in preparing samples. This work was supported, in part, by research funds from the Yamagata Prefectural Government and Tsuruoka City, Japan, and by a runner-up award fund from Kuraray/Leave a Nest to Chandran S. Abhinand in 2017. The authors also thank Karnataka Biotechnology and Information Technology Services (KBITS) and the Government of Karnataka for their support of the Center for Systems Biology and Molecular Medicine at Yenepoya (Deemed to be University) under the Biotechnology Skill Enhancement Program in Multiomics Technology (BiSEP GO ITD 02 MDA 2017).

Data availability

The data supporting this study's finding is in this article and its supplementary information. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://www.proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD038133.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any authors. The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any of the material discussed in this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chandran S. Abhinand, Email: abhinand.rohini@gmail.com

Josephine Galipon, Email: jgalipon@ttck.keio.ac.jp.

References

- Abhinand CS, Raju R, Soumya SJ, Arya PS, Sudhakaran PR. VEGF-A/VEGFR2 signaling network in endothelial cells relevant to angiogenesis. J Cell Commun Signal. 2016;10:347–354. doi: 10.1007/s12079-016-0352-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agajanian MJ, Walker MP, Axtman AD, Ruela-de-Sousa RR, Serafin DS, Rabinowitz AD, Graham DM, Ryan MB, Tamir T, Nakamichi Y, Gammons MV, Bennett JM, Couñago RM, Drewry DH, Elkins JM, Gileadi C, Gileadi O, Godoi PH, Kapadia N, Müller S, Santiago AS, Sorrell FJ, Wells CI, Fedorov O, Willson TM, Zuercher WJ, Major MB. WNT activates the AAK1 kinase to promote clathrin-mediated endocytosis of LRP6 and establish a negative feedback loop. Cell Rep. 2019;26(1):79–93.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Cazares D, Chavez-Dominguez R, Carlos-Reyes A, Lopez-Camarillo C, Hernadez de la Cruz ON, Lopez-Gonzalez JS. Contribution of angiogenesis to inflammation and cancer. Front Oncol. 2019;12(9):1399. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouïs D, Kusumanto Y, Meijer C, Mulder NH, Hospers GAP. A review on pro- and anti-angiogenic factors as targets of clinical intervention. Pharmacol Res. 2006;53:89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce JI, Shuttleworth TJ, Giovannucci DR, Yule DI. Phosphorylation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in parotid acinar cells. A mechanism for the synergistic effects of cAMP on Ca2+ signaling. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(2):1340–1348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407:249–257. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature. 2011;473:298–307. doi: 10.1038/nature10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaar Z, O'reilly P, Gelman I, Sabourin LA. v-Src-dependent down-regulation of the Ste20-like kinase SLK by casein kinase II. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(38):28193–28199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605665200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Heukamp LC, Siobal M, Schöttle J, Wieczorek C, Peifer M, Frasca D, Koker M, König K, Meder L, Rauh D, Buettner R, Wolf J, Brekken RA, Neumaier B, Christofori G, Thomas RK, Ullrich RT. Tumor VEGF: VEGFR2 autocrine feed-forward loop triggers angiogenesis in lung cancer. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1732–1740. doi: 10.1172/JCI65385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng A, Grant CE, Noble WS, Bailey TL. MoMo: discovery of statistically significant post-translational modification motifs. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(16):2774–2782. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin CH, Chen SH, Wu HH, Ho CW, Ko MT, Lin CY. cytoHubba: identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Syst Biol. 2014;8(Suppl 4):S11. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-8-S4-S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou MF, Schwartz D. Biological sequence motif discovery using motif-x. Curr Protoc Bioinf. 2011;13:15–24. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1315s35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke DJB, Kuleshov MV, Schilder BM, Torre D, Duffy ME, Keenan AB, Lachmann A, Feldmann AS, Gundersen GW, Silverstein MC, Wang Z, Ma'ayan A. eXpression2Kinases (X2K) Web: linking expression signatures to upstream cell signaling networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W171–W179. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner SD, Schmid SL. Identification of an adaptor-associated kinase, AAK1, as a regulator of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2002;156(5):921–929. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S, Aldrich TH, Jones PF, Acheson A, Compton DL, Jain V, Ryan TE, Bruno J, Radziejewski C, Maisonpierre PC, Yancopoulos GD. Isolation of angiopoietin-1, a ligand for the TIE2 receptor, by secretion-trap expression cloning. Cell. 1996;87(7):1161–1169. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81812-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejana E. The role of wnt signaling in physiological and pathological angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2010;107:943–952. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eid S, Turk S, Volkamer A, Rippmann F, Fulle S. KinMap: a web-based tool for interactive navigation through human kinome data. BMC Bioinf. 2017;18(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s12859-016-1433-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng JK, McCormack AL, Yates JR. An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1994;5(11):976–989. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N. Molecular and biological properties of vascular endothelial growth factor. J Mol Med. 1999;77:527–543. doi: 10.1007/s001099900019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N, Houck K, Jakeman L, Leung DW. Molecular and biological properties of the vascular endothelial growth factor family of proteins. Endocr Rev. 1992;13:18–32. doi: 10.1210/edrv-13-1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1182–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J, Klagsburn M (1987) Angiogenic factors. Science 235(4787):442–447. 10.1126/science.2432664 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Folkman J, Shing Y (1992) Angiogenesis. J Biol Chem 267(16):10931–10934. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)49853-0 [PubMed]

- Grønborg M, Kristiansen TZ, Stensballe A, Andersen JS, Ohara O, Mann M, Jensen ON, Pandey A. A mass spectrometry-based proteomic approach for identification of serine/threonine-phosphorylated proteins by enrichment with phospho-specific antibodies: identification of a novel protein, Frigg, as a protein kinase A substrate. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1(7):517–527. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200010-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes K, Roberts OL, Thomas AM, Cross MJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2: structure, function, intracellular signalling and therapeutic inhibition. Cell Signal. 2007;19:2003–2012. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch S, Tugues S, Li X, Gualandi L, Claesson-Welsh L. Signal transduction by vascular endothelial growth factor receptors. Biochem J. 2011;437:169–183. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig T, Menze BH, Kirchner M, Monigatti F, Parker KC, Patterson T, Steen JJ, Hamprecht FA, Steen H. Robust prediction of the MASCOT score for an improved quality assessment in mass spectrometric proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2008;7(9):3708–3717. doi: 10.1021/pr700859x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohela M, Bry M, Tammela T, Alitalo K. VEGFs and receptors involved in angiogenesis versus lymphangiogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:154–165. doi: 10.1089/15279160175029434410.1016/j.ceb.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann M, Jensen ON. Proteomic analysis of post-translational modifications. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(3):255–261. doi: 10.1038/nbt0303-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng EW, Adamis AP. Targeting angiogenesis, the underlying disorder in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Can J Ophthalmol. 2005;40(3):352–368. doi: 10.1016/S0008-4182(05)80078-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida N, Yano H, Nishida T, Kamura T, Kojiro M. Angiogenesis in cancer. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2006;2:213–219. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.2006.2.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent MA, Iozzo RV. Fibroblast growth factor-2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2000;32(2):115–120. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Flaherty C, de Lamirande E, Gagnon C. Phosphorylation of the Arginine-X-X-(Serine/Threonine) motif in human sperm proteins during capacitation: modulation and protein kinase a dependency. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10(5):355–363. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oklu R, Walker TG, Wicky S, Hesketh R (2010) Angiogenesis and current antiangiogenic strategies for the treatment of cancer. J Vasc Interv Radiol 21(12):1791–1805. 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ortega N, Hutchings H, Plouët J. Signal relays in the VEGF system. Front Biosci. 1999;1(4):D141–D152. doi: 10.2741/A417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil AH, Datta KK, Behera SK, Kasaragod S, Pinto SM, Koyangana SG, Mathur PP, Gowda H, Pandey A, Prasad TSK. Dissecting Candida pathobiology: post-translational modifications on the candida tropicalis proteome. OMICS. 2018;22(8):544–552. doi: 10.1089/omi.2018.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlowska Z, Baranska P, Jerczynska H, Koziolkiewicz W, Cierniewski CS. Heat shock proteins and other components of cellular machinery for protein synthesis are up-regulated in vascular endothelial cell growth factor-activated human endothelial cells. Proteomics. 2005;5(5):1217–1227. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova TV, Makinen T, Alitalo K. Signaling via vascular endothelial growth factor receptors. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253(1):117–130. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi N, Costello CE. Emerging roles of post-translational modifications in signal transduction and angiogenesis. Proteomics. 2015;15(2–3):300–309. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsbottom KA, Prakash A, Riverol YP, Camacho OM, Martin MJ, Vizcaíno JA, Deutsch EW, Jones AR. Method for independent estimation of the false localization rate for phosphoproteomics. J Proteome Res. 2022;21(7):1603–1615. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.1c00827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappsilber J, Ishihama Y, Mann M. Stop and go extraction tips for matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization, nanoelectrospray, and LC/MS sample pretreatment in proteomics. Anal Chem. 2003;75(3):663–670. doi: 10.1021/ac026117i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudvere U, Kolberg L, Kuzmin I, Arak T, Adler P, Peterson H, Vilo J. g:Profiler: a web server for functional enrichment analysis and conversions of gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W191–W198. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarpia L, Lippman SM, El-Naggar AK. Targeting the MAPK-RAS-RAF signaling pathway in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16(1):103–119. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.645805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seldin DC, Leder P. Mutational analysis of a critical signaling domain of the human interleukin 4 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(6):2140–2144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumya SJ, Athira AP, Binu S, Sudhakaran PR. mTOR as a modulator of metabolite sensing relevant to angiogenesis. In: Maiese K, editor. Molecules to medicine with mTOR: Translating critical pathways of the mammalian target of rapamycin into novel therapeutic strategies. Elsevier Science & Technology Books. Academic Press; 2016. pp. 229–243. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks LM, Moro C, Ukropcova B, Bajpeyi S, Civitarese AE, Hulver MW, Thoresen GH, Rustan AC, Smith SR. Remodeling lipid metabolism and improving insulin responsiveness in human primary myotubes. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7):e21068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama N, Masuda T, Shinoda K, Nakamura A, Tomita M, Ishihama Y. Phosphopeptide enrichment by aliphatic hydroxy acid-modified metal oxide chromatography for nano-LC-MS/MS in proteomics applications. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6(6):1103–1109. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T600060-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunitha P, Raju R, Sajil CK, Abhinand CS, Nair AS, Oommen OV, Sugunan VS, Sudhakaran PR. Temporal VEGFA responsive genes in HUVECs: gene signatures and potential ligands/receptors fine-tuning angiogenesis. J Cell Commun Signal. 2019;13(4):561–571. doi: 10.1007/s12079-019-00541-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Nastou KC, Lyon D, Kirsch R, Pyysalo S, Doncheva NT, Legeay M, Fang T, Bork P, Jensen LJ, von Mering C. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D605–D612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taus T, Köcher T, Pichler P, Paschke C, Schmidt A, Henrich C, Mechtler K. Universal and confident phosphorylation site localization using phosphoRS. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(12):5354–5362. doi: 10.1021/pr200611n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonnesen MG, Feng X, Clark RAF. Angiogenesis in wound healing. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2000;5:40–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1087-0024.2000.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres M. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in redox signaling. Front Biosci. 2003;8:d369–d391. doi: 10.2741/999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S, Storbeck CJ, Roovers K, Chaar ZY, Kolodziej P, McKay M, Sabourin LA. FAK/src-family dependent activation of the Ste20-like kinase SLK is required for microtubule-dependent focal adhesion turnover and cell migration. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(4):e1868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Singh AR, Zhao Y, Du T, Huang Y, Wan X, Mukhopadhyay D, Wang Y, Wang N, Zhang P. TRIM28 regulates sprouting angiogenesis through VEGFR-DLL4-Notch signaling circuit. FASEB J. 2020;34(11):14710–14724. doi: 10.1096/fj.202000186RRR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CF, Wang R, Liang Q, Liang J, Li W, Jung SY, Qin J, Lin SH, Kuang J. Dissecting the M phase-specific phosphorylation of serine-proline or threonine-proline motifs. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21(9):1470–1481. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e09-06-0486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Oh J, Li F, Kwon Y, Cho H, Shin J, Lee SK, Kim S. New scaffold for angiogenesis inhibitors discovered by targeted chemical transformations of wondonin natural products. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2017;8(10):1066–1071. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang G, Yu K, Jiang Z, Chung A, Yao J, Ha C, Toy K, Soriano R, Haley B, Blackwood E, Sampath D, Bais C, Lill JR, Ferrara N. Phosphoproteomic analysis implicates the mTORC2-FoxO1 axis in VEGF signaling and feedback activation of receptor tyrosine kinases. Sci Signal. 2013;6(271):ra25. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study's finding is in this article and its supplementary information. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://www.proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD038133.